Chapter 2, I began walking up the Himalaya Mountains

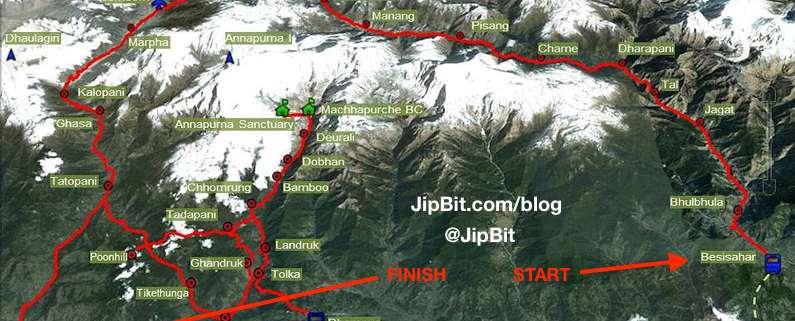

Nature is my church, and I felt like I was in heaven within a half hour of walking uphill from the trailhead in Besi Sahar. I had left the smog and car horns of 2 million people in Kathmandu, and had arrived in a secluded, rural area with neither a person in sight nor an automobile within hearing distance.

The weather was perfect. I wor a pair of shorts, a moisture-whicking t-shirt, a thin long-sleeve overshirt, and a wide brimmed hat to protect my pale skin from the high altitude sun.

The sky was blue, with a few white clouds drifting as aimlessly as I hoped to. I was surrounded by a thick forest of trees, and walking along a trail barely wide enough for two people. I could hear the roar of a river to my left, but far in the distance, and knew I was walking in the right direction. I’m sure the pain in my body was still there, but I was only aware of the flow of nature.

My thoughts bounced all over the place, mostly telling myself again and again how amazing it is to be hiking in the Himalayas two weeks after my doctor and I had discussed if it were a wise decision. And how fortunate I was that the airplane ticket was so inexpensive, and how unfortunate it was for the Nepalis who had suffered through a civili war and earthquake.

I grew tired of my thoughts, and tried to steer them to something enjoyable, so I turned on my mental radio and played a few songs. The first was “On the Road Again,” by Willie Nelson.

“I just can’t wait to get on the road again.

Making music with my friends,

I can’t wait to get on the road again.”

I hummed along to my mental radio for a few hours, and allowed my mind to explore the foothills of the Himalayas.

I was on the West side of a river, and I could hear water crashing in the canyon to my left. Winter was approaching, and the trees had begun to shed their green color, and adapt to diminished light with ambers and hues that would better absorb the precious energy spectrum of a sun setting lower in the sky at the beginning of autumn.

The air did not smell like the smog of Kathmandhu, layered with inadequate sewage systems unable to handle the biowaste of 2 million people. The Annapurna circuit trail began in a thick forest at 760 meters, and it smelled like new leaves growing and old leaves decaying. I breathed deeply as I hiked, and my body responded to old associations by releasing endorphins that camoflaged my body’s pain, and distracted my mind from attaching to the pain and reliving those associations.

I stopped and adjusted the length of trekking poles I had bought in Kathmandu. They were labeled as a famous and expensive brand, but I knew they were fake. Knock offs, probably mass produced in adjacent China, and were offered by dozens of shops in the tourist district of Kathmandu, along Kosan Road, where guides hawked their services, and mystic gurus promised young backpackers enlightenment for $100.

I paid $10 for the poles, I missed my expensive, ultralight, carbon fiber poles that had escaped from my backpack somewhere between California and Nepal. Carbon fiber absorbed vibrations more than stiff aluminum, and the cork handles reduced sweating compared to plastic, and I didn’t have to grasp them as tightly. My poles had protected my sore wrists and finger, in addition to reducing weight on my hips, knees and ankle. And they were fun. I had had learned to use them as an extension of my body, providing balance as I danced across loose stones and tree roots, and the ultralight carbon blended into a one-meter long extension of my arms.

The knock off poles were thick aluminum, and had a spring mechanism to absorb shocks. But, you get what you pay for, and for $10 I had bought heavy poles with plastic handles, and springs that squeaked with every step. I couldn’t adjust them, so I opened the top flap of my backpack and removed a Leatherman multi-tool, then disassembled the poles and found the spring. I added some sunscreen to the spring, reassembled the poles, and tested the height. They were perfect for the slight uphill walk. I repacked, and continued squeak-free, pleased with my past self for having justified carrying the extra half-pound of a Leatherman tool.

An hour later, my mind wandered, probably like many people who are in their church for a long time. I steered my mind towards my goal: Throrong Pass. It’s is one of the world’s highest mountain passes, surrounded by Annapurna Peak and other famous Himalayan mountains, and usually covered with ice and snow, and is where the 32 people trapped in a snowstorm died three years before.

Thornog Pass was at 5,416 meters elevation. Or, as we say in the United States, 3.7 miles in the sky. The trailhead began at 760 meters. I performed quick mental math, and I’d have to walk uphill another 2.9 miles. I tried stopped thinking about that, and turned my radio back on. Willie was waiting for me, and together we hiked another hour until we reached our first tea house.

Tea houses used to be tea houses, a place to rest and sip hot tea, but now the name implies anywhere a traveler can rest for the night. When tourists began hiking the Annapurna circuit 30 or 40 years ago, people who lived near the trail opened their homes as guest houses during the trekking season, approximately three months a year, and subsized their livelihood with tourist dollars.

A tea house bed costs approximately $1 to $7. The owners usually offer dinner and breakfast for another dollar or two, and a few of them had installed gas or solar powered hot plates in their showers so that tourists could take a hot shower. You could loop the Annapurna circuit again and again, until you ran out $3 a day for food, shelter, and hot showers. I had enough in my wallet to walk the loop for a few hundred years, but I didn’t plan on staying that long. I like not having a deadline, but three months was the most I’d like to be gone from home at this point in my life.

I slid out of my backpack, and plopped on the porch of first tea house. No one was home. Peak trekking season had ended, so the owners were probably not expecting a guest. I sipped water from my Nalgene bottle, and fanned my shirt to air out my sweaty back.

When I cooled off, I decided my backpack was too heavy, so I unpacked it and reaccessed what I had thought was critical to bring when I had been a few hundred meters lower elevation, and not remembering what it would be like to hike 3 miles uphill with a heavy backpack. My body was 46 years old, but my mind still thought we had the body a 26 year old young man, and I tended to push myself too hard when I first start hiking.

My 46 year old self and 26 year old self never agree on what to pack, but at that moment both agreed that we should leave some things behind. I set aside a few books that no longer seemed as important to carry, and began a pile that I’d leave on the porch of the guest house. Leaving items was common. Most people have a self that packs their bags, and a self that has to carry what they packed. The first few guest houses probably made more money selling abandoned luxuries than they did renting $1 beds.

I set aside my water bladder, the type that sits close to your back and carries 3 liters of water. I had a water filter and two Nalgene bottles, and now that I had seen the river I knew I’d be fine without carrying the bladder. Leaving 3 liters of water would reduce my backpack by 3 kilograms. Or, as we say in America, 6.6 pounds. The bladder, plus the books, was at least 10 unnecessary pounds.

I continued reassessing each item, and was disappointed that I had only reduced my backpack by, at most, 15 pounds. I sat down again, opened a snack bar, and nibbled on it as I looked at what I still felt was necessary to carry.

I had three Leatherman tools, by accident. I had planned on taking one, but I couldn’t decide which one. Each has a purpose, but I didn’t know where I’d end up on this trip, so I packed all three and intended to remove two after I read my travel books. I had forgotten them, of course, and discovered them my first night in Kathmandu. Now, I was carrying them, and knew they added over a pound of extra gear.

But, I couldn’t bring myself to leave them, and hoped I’d stumble across a Nepali who needed a knife, or pliers, or screwdriver; I imagined the look on their face if I helped them, then gave them the tool so they could help others. I smiled at the thought of that future, and that made the extra pound worthwhile.

I kept my Lonely Planet for Nepal. I also kept the version for India, which was massive. It weighed a pound, and took up valuable space in my backpack. But, I had bought my return airplane ticket from Delhi India, and planned to get there overland after I left Nepal. I doubted I’d find another copy, and I enjoyed reading guide books. I read them like some people read novels, and I looked forward to curling up with it at night. I also kept a few small books I wanted to study. Combined, they were only a few pounds.

I had clothes for all weather climates, including the hot deserts in India I’d like to see, and the frozen tundra I expected 3 miles in the sky. Surprisingly, I didn’t bring a lot of clothing. I wore layers of Merino wool, a natural product that’s more efficient at a wider temperature range than any manmade material. The nano fibers absorb body sweat when you walk, but will still keep you warm. Cotton can kill people, because it steels your body heat when its wet; I hadn’t heeded that once, and would never trek in snow with cotton again. Merino wool was an ideal solution to versatile clothing.

Merino wool allows moisture to slowly evaporate releases the water when you’re hot, and the endothermic reaction cools your body. Best yet, Merino wool is antimicrobial. You can go weeks without washing it, and it won’t stink.

I had three long sleeve Merino shirts, two synthetic moisture wicking t-shirts, one cotton t-shirt for sleeping, five pairs of underwear from a company that specialized in travel gear – they were lightweight, easy to wash, and quick to dry. I also had five pairs of socks made for trekking, and planned on washing them every few days.

I had a bathing suit, so I left a pair of shorts that didn’t seem as important now. I was wearing walking shoes, and carried sandals. At night, I’d wear the sandals while the shoes dried.

I had a waterproof windbreaker jacket, ultralight and compressible down jacket, and rain poncho that wold cover me and my backpack, and could be made into an emergency tent. I left my sleeping bag, because the guide book said tea houses almost always have extra blankets. I had spoken with a few tourists on Kosan Road, and they said they found plenty of blankets on the circuit a month before.

I used my yoga mat as a sleeping pad, and my jacket as a pillow, so I was prepared for emergency sleeping, if necessary. Of course, I had emergency lighters and parachord, and could build a shelter and fire if necessary, but I didn’t plan on that. I enjoyed hot showers and home cooked mood to much.

I kept the Frisbee. I had even weaved a net of parachord, and strapped the Frisbee to my backpack with quick and easy access, in case of an emergency.

I repacked everything, and put my bag back on. I knew it was 10 pounds lighter, but I didn’t feel much better. I stopped ruminating about my knives by turning my mental radio back on and walking again.

Willie and I made good time, and soon I was crossing a thin suspension bridge, barely wide enough for my backpack. The bridge was secure. A foreign country, I think New Zealand, had funded building them. Before, the trail would have zig-zagged a few hundred steep feet down to the river, the switchbacks necessary because of the steep slopes that would be impossible to herd cattle otherwise.

The thick cables spanned at least two hundred feet, and though I knew they could support much more weight then I would add, the sensation was terrifying. The bridge swayed with every step, and I could look down and seen the river I had hear roaring through the canyon. It cascaded over giant boulders, and I became lost in vertigo looking down.

I was awakened by the bridge swaying without me walking. I looked up and saw a pair of horns headed towards me and spanning the width of the bridge so that I couldn’t pass. A bull was walking towards me, and several more followed him. Their shepard slapped the trailing one on its rump, and they all moved forward quickly, and the bridge swayed more than was okay with me.

I had read in the Lonely Planet that livestock had the right-of-way, but I wouldn’t have needed to know that custom to see that I should retreat. I scurried back to my side of the canyon, and let the horns and sheppard pass. As he approached, I clasped my hands together with my palms open, bowed slightly, and said, “Namaste.” He returned the gesture and word when he stepped on my side of the trail, and as soon as he looked back up I hurried across the bridge and reminded myself that though I didn’t have a schedule, it would be dark in a couple of hours, and I would prefer to sleep in a tea house than on a narrow trail frequented by cattle.

But I couldn’t help but pause on the other side of the bridge. I was back in heaven, and I was staring up at cathedrals carved 75,000 years ago by retreating glaciers. Sheer granite cliffs soared into the sky upriver, and I was stunned by how high big they seemed, and how small I felt. I squinted, because I wasn’t wearing my glasses, and imagined I saw a dot moving high on the cliff. I pulled my phone from my backpack and took a photo of the cliff, and when I zoomed in on the digital image, I could see a tiny person leading a few yaks along switchbacks cut into the cliff.

The Annapurna circuit went through rural areas without roads, and people still herded cattle and sheep, like they had for thousands of years. I had no idea how far away I’d start seeing yaks, but the anticipation gave me a burst of energy, and I continued walking through my church without worrying about extra weight or heavy trekking poles. There are no regrets in heaven.

I had to wear my headlamp within an hour, and about 30 minutes later I came upon a few houses packed against the trail. Owners must have seen my light approaching, and they were waiting by their doors with promises of luxuries bedding and home cooked meals. None of them had greeted me with “Namaste” before listing what they sold, which wasn’t the experience I hoped for. I walked past them, and approached a roaring waterfall with a hydroelectric generator. The sound was thunderous, but not unpleasant, and their was a boy playing near it, throwing rocks into the waterfall.

He was illuminated by spotlights on top of the hydroelectric plant. I turned off my headlamp, clasped my hands, bowed, and said, “Namaste.” He did the same, and said, “Hello! Where you from?” in broken English. I decided this was an emergency, so I took off my backpack and slid out my Frisbee. I held it up, paused long enough for him to study it from 20 feet away, then tossed it gently towards him. I added enough lift that it would drift down slowly. He caught on, then caught the Frisbee. Almost instantly he tried to throw it back to me by mimicking what he thought I had done, and a few minutes later I was showing him how to throw it level, not upwards, and to spin his wrist at the last moment. Like most kids, he learned quickly when it was fun, and a half hour later we were tossing back and forth from almost 20 feet.

His dad came out, said hello, and asked if he could toss the Frisbee with us. I was surprised that he spoke English so well, and that he knew what a Frisbee was. We threw from almost 80 feet away, and took turns standing near his son so that we could catch his throws.

I stayed in their tea house that night, and learned more about them over a simple home cooked bowl of rice and lentils, dal bhat in Nepali. By coincidence, it was Thanksgiving, an American holiday where meals are shared. I felt fortunate to share my Thanksgiving meal with someone who spoke English.

The man was born in a small town a few hours bus ride away, and had worked in the United States for a few years. He had sent money back to his wife and daughter to support them, then moved back when they had saved enough to buy a home along the Annapurna circuit. His son was born there.

After their son was born, China built the hydroelectic plant near the naturally occuring waterfall that had been his front yard. The roaring water camoflauged most of the artificial whine of the spinning electromagnet generator, and a smaller generator fed their small village with more than enough electricity. Power cables carried electricity from the larger plant back to China, and they were funding more generators throughout Nepals mountains. The melting snow and natural sources of water turned the electromagnets all year long, and selling electricity to China had become a lucrative export for the Nepali government in Kathmandhu.

The man’s house was about 30 feet from the cliff edge, and came all the way up to the trail. Like many tea houses, his was an elongated rectangle, squeezed into whatever space was possible between the mountain cliffs on my right, and the canyon drop off on my left.

He had partitioned five tiny rooms by placing thin plywood between bunk beds. All were empty, and I chose the one with a window not facing the bright lights of the open field surrounding the power plant.

“The noise and lights don’t keep away tourists during peak season,” he told me. “We’re usually full before lunchtime. You’re late in the season, and won’t have problems finding tea houses with room for at least two weeks.”

“What happens in two weeks?” I asked, obviously concerned by any news that would require me planning ahead.

“The election,” he said, as if that explained everything. We kept talking, and I learned that Nepal’s second democratic election was in two weeks. By Nepali law, you had to be physically present in whichever district you wanted to vote. Kathmandu had 2 million people, and, according to many people I met, corrupt politicians were elected by for-profit corporations that did things like build hydroelectric plants for China. The sparsely populated Himalayan regions didn’t have a voice, they felt, so this year all of their family members would be traveling to wherever they had been born, so that they could cast their vote for candidates from their villages.

I listened intently – it’s rare to see a country so new to democracy. The United States had been practicing it for 200 years, and we still didn’t understand or utilize it fully, and my host knew that.

“I have hope for our future,” was how he ended our conversation that evening. I went back to my room, and squeezed through the narrow door. The room was too small to do yoga, so I went back outside with my mat and stretched my tight hamstrings under the spotlights. The food in my belly quieted my mind, and I let my thoughts drift wherever they wanted.

I remembered another waterfall from a Thanksgiving dinner almost 20 years before, when my wife and I were trekking through Colca Canyon in Peru. Like the Annapurna trail, it followed a roaring river that tumbled down it’s steep canyon. Unlike Annapurna, we hiked down, not up, and it took us nine days of trekking downhill before we came upon the river. We knew that after that trip, we’d make a choice together. We’d chose whether or not to have biologic children. I was 27 years old then, and she was 29. In the southern U.S., where we were both from, most of our friends had begun having children at 18 or 19 years old, immediately out of high school. Many sooner than that. By our peers’ standards, we were old, and we should start having kids as soon as possible.

She wanted biologic children badly. I was concerned that the mental illness that ran in my family would be passed to our children, and I was beginning to enjoy the freedom of being DINKS, couples that earned Dual Incomes, and had No Kids. We had flown to Ecquador to live carefree for a few months before deciding, and had extended our trip to include Peru. By the time we camped by the river in Colca Canyon, we had been backpacking for six months.

We spent that Thanksgiving searching for Inca artifacts along the canyon. An Incan city had remained hidden deep in the canyon for a hundred years after the Spanish conquored Peru and the famous Macchu Picchu religious site a few hundred miles away, and they would have hiked the same canyon, and rested in the same areas that I was seeking out.

We had a tent, but they did not, so I envisioned where I would have camped 300 years ago, and searched those areas for arrowheads, sea shells from trading routes, and anything else I could find.

I had found an obsidian arrowhead, and joked that I was officially an archeologist.

She laughed, and asked how I’d get it back home. I said I’d transport it in any orafice necessary, and she feigned disgust while holding back laughter as I pantomimed different places I could hide it on me, and on her. We fell into each others’ arms, and I dropped the arrowhead on the ground to focus on more important things.

An hour or three later, I found the arrowhead again, and packed it away in my backpack. Obsidian chips easily, so I wrapped it in an extra shirt, and placed the package in one of my padded camera bags.

I wasn’t concerned about carrying extra weight when I was 27 years old. My cameras alone weighed 35 pounds. I had brought two Nikon N2000’s, each with a different type of film so that I’d be prepared for most photo opportunities, and an assortment of lenses. This was 2001, when digital cameras were expensive and didn’t take nearly as good of photos as film cameras.

I didn’t use trekking poles back then, and in 2016, as I stretched my sore hips and knees, and remembered the choice I’d face in a few months. I was surprised by a wave of self-pity. I returned my thoughts to the positive memories from 2001.

Deep in Colca Canyon, we bathed in a relatively still pool of water next to a small waterfall, and began preparing a dinner of dried salami, cheese that was approaching the end of it’s lifespan, and a few carrots that I had wrapped individually in paper to preserve them. Of course, I had whichever version of Leatherman tool existed back then, and she used it to slice the salami while I set up our camp stove and boiled water for tea.

As we made our Thanksgiving dinner, a man on a horse approached. He had a few mules in a caravan, and was bringing supplies from a town on the high plateau to his family deep in the canyon. He stopped his horse and greeted us in the custom of his people, and I practiced my burgeoning Quecha by offering him tea. Or, at least that’s what I thought I said. I’ve never been good at pronouncing new words, and he could have simply seen me holding out a cup of tea and known what I intended.

He spoke a few words of English, and sipped tea while trying to learn a few more. He shared fresh cheese, and we shared our old cheese and some of our salami. An hour later, before he departed, he gave us a spool of fishing string, some hooks, and a few weights, and showed me how to fish in the river.

I was in heaven for the next few days, and fished everywhere we saw a relatively still pool of water. She took the time to rest her feet in the water and read a book, and we spent a few days in silent Thanksgiving. After seven years of marriage, and traveling side-by-side for six months, we were blissful in silence. We had no where to be, and nothing to do. The deep sense of peace from being present in every moment had brought us closer than I had known a married couple could be.

Colca Canyon is the world’s deepest canyon, and we were there three years before the National Geographic expedition would tell the world that. I was writing a travel book for couples, and would call it Two To Go, and write about plays on words, like finding a deep sense of peace in the world’s deepest canyon, simply because we were not in a hurry to be anywhere and could be present with each other.

In 2016, I finished stretching next to the roar of the hydroelectric waterfall. My memories had sparked endorphins, and I was happy. I felt that was a pleasant way to end my Thanksgiving in Nepal, so I crawled into the tiny bed and listened to the 10,000 sounds of nature until I drifted off to sleep.

Return to the Table of Contents.