The War on Drugs

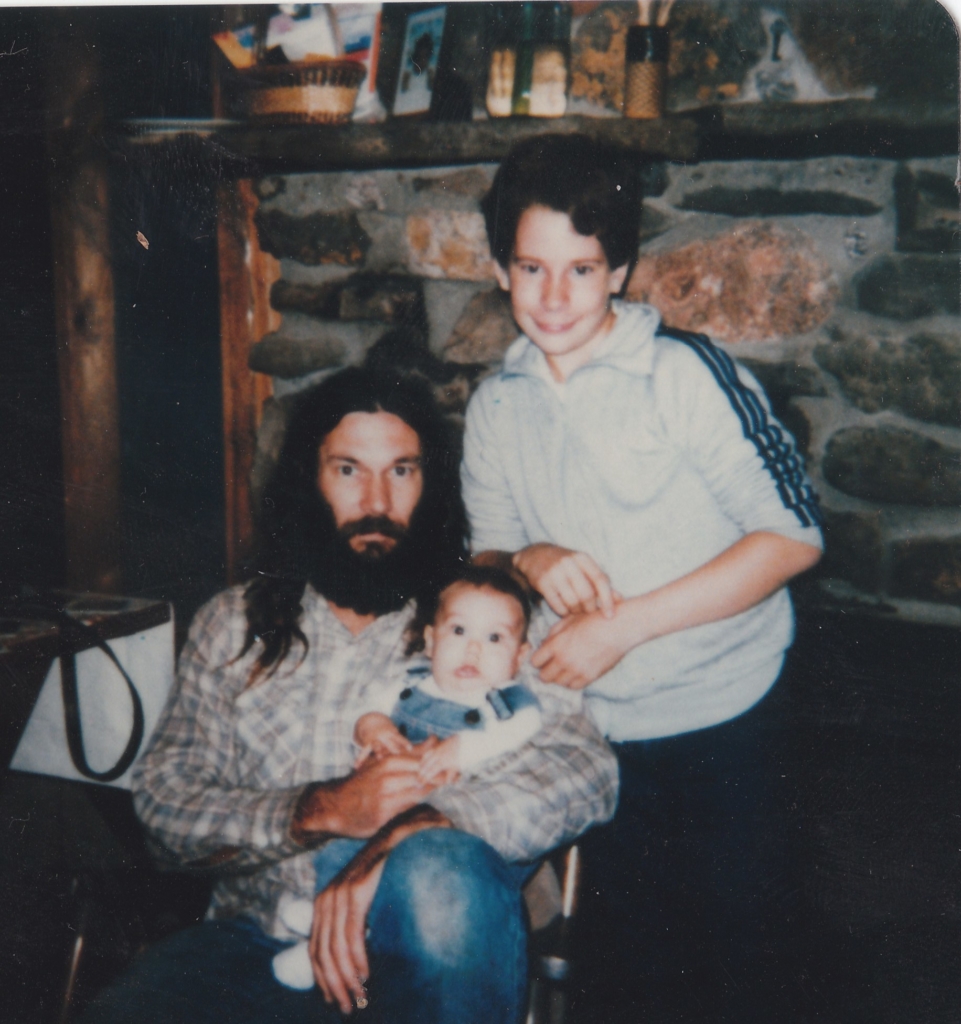

I’m not sure who’s responsible for me being a casualty of the War on Drugs. It could have been the new president, Ronald Reagan. In 1980 he promised the Evangelical Christian groups that financed his presidential campaign that he’d fight, and end, America’s drug problem. Or, it could have been my dad, who had earned enough money growing marijuana to buy remote land in the Ozark Mountains of Arkansas, where he grew even more marijuana. Either way, I at a lot ketchup in the early 80’s.

The Regan administration had said that ketchup was a vegetable, and reduced funding to my free lunch program back in Baton Rouge. Wendy was embarassed when she had to complete paperwork that admitted to the world she was poor and unable to pay for my school lunch. The news said we had to stop drugs and end the welfare state, whatever that was, so they cut costs for my lunch to pay for a war against my dad. At the time, I was ok with the part about lunch, because I liked ketchup more than vegetables.

I’m not sure what sent him to the Ozarks. We had always camped there, but now he wanted to build a permanent home deep in the woods. He walked into a real estate office in the small town of Clinton Arkansas and asked for “the most remote land they had, with access to water, like a river or stream.” He paid in cash, and became the owner of 10 wilderness acres, five miles from the nearest paved road. He was in his early 20’s, the same age Wendy’s friend, Debbie, had been when she developed szizophrenia.

I knew a lot of adult words, but didn’t always understand them.

Our land was remote, and it had a creek. The directions from the real estate office were confusing. If you drove there from Clinton, you’d drive along Route 1, a small and winding road cut through the rolling mountains. You wouldn’t see houses or signs of people for almost 30 miles, then you’d see a small sign saying that you’re passing through Alread Arkansas, population 506. You would have already passed it before you wondered if there were exactly 506 people there, and if they changed the sign every time someone died or was born in Alread.

When you realized you missed Alread, you’d look over your shoulder and see the back of a similar sign for drives going the opposite direction. If you turned around and drove back, you’d notice a small trailer in a dirt driveway on your left. It had a hand-painted sign that said “Johnson’s General Store.” Inside the general store, the Johnson’s had installed two coin operated washing machines and a dryer next to a small bookshelf half-filled with new rolls of toilet paper, cans of vegetables, and toothpaste. If you called out, Mrs. Johnson or one of her sons would come out to sell you something, if they were home.

Johnson’s store was was next to a dirt road barely wide enough for two small cars to pass. There were 7 or 8 mailboxes before the road. A mailman could fill them from the paved road as they drove along Route 1 between Clinton and Morilton. An old piece of 2X4 lumber was nailed to a fence post near the mailboxes; it was faded, but if you looked closely you could read “Johnson Road,” which somehow didn’t seem to be the official name, and the mailman probably didn’t need it, but at least it allowed me to tell Wendy that my dad lived off Johnson Road.

Johnson Road curved right after about two miles. Another road went to the left, but it was more like a water runoff than a road. It may have once been a road, but without a bulldozer to smooth big rocks that are exposed during spring rains it quickly became impassable.

The Johnson family provided bulldozer services, of course. Someone had to maintain Johnson Road. My dad had paid to smooth the impassable section so he could reach his parking spot, and he paid them to dig a small pond for horses and cattle he imagined owning one day.

The impassable part of Johnson Road ended at a small parking spot before the road began angling downhill steeply. Even when the impassable part had been bulldozed, it would have been foolish to attempt going down the steep section in anything other than a 4X4 jeep with high clearance, and that jeep should be driven by someone experienced navigating over boulders and through rapidly flowing rivers. The Johnson’s bulldozed an area big enough for two or three cars at the top of the steep section of road; if you didn’t have a 4×4 with high clearance, or a bulldozer on tread wheels, like a tank, you could park here and keep walking.

Two miles and two creek crossings later you’d find my dad’s land. It was virgin land, without a building. The trees came from the mountain top all the way to Little Archie Creek, which was the border of our land. We had no electricity, no phone, and no running water; he couldn’t have been happier.

With money from last year’s Louisiana marijuana harvest he bought a civilian version of a WWII jeep, the CJ-7, and shuttled tools and supplies between the parking spot and our future home. He bought chainsaws and axes, and used the wood from trees he cut down to build a barn where those trees had stood. It was a simple barn. He didn’t add walls to shield us from rain or wind; it was meant to keep rain off and let air flow across the wood he stacked inside, which would become our log cabin by the time I returned six months later.

From ages 8 to 13, I went to school in Louisiana and spent three months in Arkansas each summer, even though Alread had a one room school. All kids sat in the same room, and the teacher had different lessons for each of them. There was a gun rack in her office, so that kids could lock up their hunting rifles before class. I went to school in Baton Rouge, which had more strict gun control laws for elementary school, so I did most of my hunting in Arkansas.

Holidays were flexible, and I usually spent at least one or two weeks there in winter. I’d spend a Thanksgiving in November or a Christmas in December or a spring break in April. or some combination of them. I’d coordinate meeting my dad, so he and Wendy had almost no more contact with each other.

He’d pick me up in Baton Rouge after my last day of school in the spring, and we’d drive the 500 miles between Baton Rouge and Alread in eight hours. His Chevy had an 8-track cassette player, and we alternated between listening his dozen or so cassettes and local radio stations, if they played good music. My dad liked a combination of 1970’s pop rock and country music, but his favorite cassettes were by Fleetwood Mac. He still thought Stevie Nicks was fine, and we listened to Rumors at least twice on the drive.

He smoked two or three joints in the 8 hours it took to reach Alread Arkansas. If we were in his car he cracked the window to allow most of the smoke to leave, but still allow the air conditioner kept us cool. When he drove the jeep, it’s torn canvas top flapped and let in the wind, so he didn’t have to crack the window when he smoked. He said he was fine driving with two or three joints; back then, the evil weed wasn’t as potent as the cultivated marijuana strains people enjoy today. He was even able to roll joints while driving; he’d steer with his knees so that one hand could hold a little pieces of paper as the other hand packed it full of green herb. I thought Bryan rolling joints with one hand was more cool; besides, I had driven, so seeing my dad drive with his knees wasn’t impressive any more.

In Arkansas, we slept on mattresses placed on top of piles of wood in his barn. His mattress was next to mine, but about three feet higher because that’s how the wood had been stacked. The wallless barn was built to keep wood dry, and there wasn’t a plan to make it comfortable. It kept morning dew off of our blankets, and let me sleep with the smells of nature and sawdust, and to hear animals venturing to the new building in their forest.

He quickly created a rudimentary garden. By the end of the first summer, there were tomatoes and corn and beans and potatoes. It improved every time I visited, and he started planting fruit trees where the pine and oak trees had grown before we cut them down to build a cabin. His days were mostly spent improving his homestead; his ritual was to wake up, stretch, smoke a joint, eat, then work with his hands until he was tired. He’d jump in Archie Creek to bathe, eat dinner, and get high while playing his guitar by firelight. He was 24 or 25 years old; he was in heaven.

He had made friends in Arkansas while I was in school in Louisiana, and some of the young women would occasionally stay over. When he wasn’t fucking one of them in the mattress next to me, he would tell me a story he remembered reading when he was my age. He had only read one book as a kid, Where the Red Fern Grows. It had been published in 1964, and was a popular book to assign in middle school or early high school English classes. There wasn’t much else to do after the sun went down, so I listened.

He would spend about twenty minutes telling the story every night we were alone, remembering it 15 years after having read it. He understood the story. He didn’t recite it word-for-word, but he had understood the messages of the book in the order of it’s chapters, and he knew the art of story telling. He created images in my mind with his stories. It wasn’t “the protagonist” of a story, it was Billy loving his dogs, and his dogs loving him. And it had happened in the Ozark Mountains, near our cabin.

The story was in first person, told by an older William, who saves a dog in his city and sits down afterwards to remember the story of his first dogs, Dan and Ann, seventy years before. Every night, it was as if William was telling me his story, one chapter a night, from my dad’s mattress. For the first summer, our dog, Ann, hunted with us, just like Billy’s dogs had hunted with him in the same mountains.

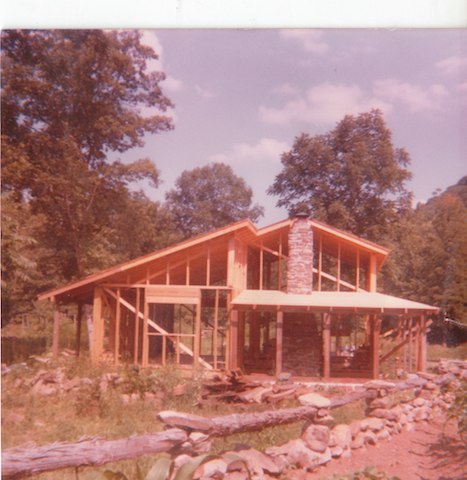

We built a log cabin 20 yards from the edge of Little Archie Creek using dry wood stored in the barn. The logs had been trees where the cabin was being built. They were irregular in shape, and they left large gaps in the walls. We mixed grass and mud into a putty that filled the gaps and blocked wind and most rodents from entering the cabin. I say we, but I only helped with the foundation and the fireplace before I returned to Louisiana that year.

We searched the valley for rocks to use for the fireplace and foundation. We wanted rectangle-shaped rocks, though most were like ovals from tumbling through the creek bed during floods. We did our best, and used concrete cement to hold them together. I wasn’t strong enough to mix shovels of small gravel into the cement, so my dad did that while I stacked rocks and spread the wet cement between them.

We had walls out of uncut logs that had been trees on that spot a year before. It seemed miraculous to sleep behind something that blocked wind. And we had a fireplace to warm us, cook in, and to heat water for bathing. Anyone who bathed in Little Archie Creek during the winter knew that warm water was a wonderful luxury to be appreciated.

He bought kerosene lanterns for light, and a kerosene stove for cooking when it wasn’t cold enough for a fire. At night, we’d play chess or poker by lamplight, listen to country music on a small AM radio with one speaker – FM radio waves didn’t reach inside the valley – and my dad played the guitar. He bought me a mandolin, and tried to teach me to play bluegrass music with him. I’m extremely untalented musically; after sunset I practiced magic tricks with his poker cards or immersed into one of the seemingly limitless hobbies I practiced from Baton Rouge library books. A lot of the books I brought were about wilderness survival, woodworking, and first aide; a few were about kids who lived off the land, free from the rules of society, like I did with my dad for a few months a year.

The creek was our sink, water supply, bathtub, food supply, and recreation. Our toilet was the ground; a U.S. Census report from that time said that 600,000 American homes still used outhouses, and we weren’t even yet one of them: we pooped in an open pit that he used as fertilizer for his pot plants. Eventually he built an outhouse, but it attracted bees and wasps and snakes, and was smelly and claustrophobic inside, so for the next few years we pooped in the pit. The flies were grateful; I tried to not imagine where they had been before they landed on our dinner plates.

In summer, we cooked outside on fire pits. In winter, we cooked inside on a wood burning stove. We used that stove to heat water for bathing once every a week or two. But, you can only get so clean standing by the fire, wiping yourself with a warm rag, so before taking me back to Wendy, he’d make me bathe in Archie Creek. It was cold, and I would cry and say I didn’t want to bathe, that I’d go home dirty. He wouldn’t say much in return, but he would throw a rock into the creek to break the layer ice, then he would throw me into the opening. He’d throw a bottle of peppermint-smelling soap after me, and tell me I couldn’t come out until I had bathed. I’d cover myself in soap as quickly as I could, then stand on rocks as water rushed past my stomach until, somehow, I managed to dunk my head underwater and rinse the peppermint smelling soap from my hair.

The road to our cabin went through my bathtub for the same reason we used it as a bathtub; it was wide, but shallow, and flowed more slowly than the rapids tumbling over rocks ten yards away. Only 4X4 vehicles could make the drive. Even then, the road was often blocked because of high water or thick ice. On those days, we parked a mile away, before the first creek crossing, and took a canoe across a large section of Archie Creek. We’d put groceries or tools in backpacks so that we could carry them to the cabin, and keep the canoe on our side of the creek until we had to go to town again. Before crossing the creek, we’d drag the canoe through the woods and put it in the water 50 yards upstream from the rapids; by the time we crossed the 20 yard creek we would have drifted dangerously close to the rapids. It was fun; people pay a lot of money to do things like that on vacation. But it was unreliable, especially with spring floods and winter ice, so he built a bridge over a narrow part of the creek. I returned from Louisiana one summer to be slightly disappointed that we could now walk instead of paddle the canoe home. But I was happy that the canoe was still there, and I could fish from it any time, when I wasn’t fishing from our new bridge.

The creek was too dangerous to cross after a heavy rain. It flooded quickly, and the rapids splashed and burst through boulders. We couldn’t paddle the canoe fast enough to reach the other side safely, so we never ventured into the rapids. Unless my dad was high, then it was fun. He had cheap inflatable rafts, like ones you’d use in a swimming pool, and we’d ride them down the rapids, naked or in cutoff jeans, after he had smoked a couple of joints. Once, my raft flipped over and trapped me under a log, unable to breathe because the rapids rushed over my body and the plastic raft trapping me against the submerged log. Ed jumped off his raft and somehow plowed back upstream to free me. When he wanted to do something, nothing stopped him from plowing through anything in his way, and that’s what saved my life that day.

He plowed his way upriver, taking huge steps that pulled each foot as high out of the force of rapid water as possible. He pushed through fallen tree branches, and kicked boulders out of his way. I had stopped struggling, and time had slowed down, so I could see clearly through the clear water of Archie Creek. I looked up and recognized sunlight coming through about two feet of tumbling water that pummeled me down with more force than my 8 year old body could resist. I saw a blur block the sunlight, then I saw his arm come through the bubbling water and grab me. I felt the two feet of tumbling rapids push against my face as my dad pulled me into sunlight and air with all of the force of a father fighting for his son’s life. I don’t remember if he had a wet joint in his mouth – it wouldn’t have surprised me, he was talented at everything with a joint.

“Are you OK? Jason! Look at me! Are you OK?”

I was ok, but I was dazed and confused. Time returned to normal, but I was in and out of consciousness as I coughed water out of my lungs. I think I said something, but I may have imagined a confident and nonchalant reply, or a joke that would have made me seem as rough and tough as a Partin should be.

I remembered Keith’s big arm carrying me to safety; my dad always felt guilty he hadn’t been there to help me when Keith and Pa Pa saved me after I fell from the fence. I was grateful, and we laughed about his rescue later, but even as I kid I recognized the difference between Keith’s big arm and Ed’s big arm; Keith hadn’t put me in harms way, I had climbed there on my own. I started learning to take better care of myself. It would take a long time to reach a hospital via Johnson Road.

Our nearest neighbors were five miles away, back up our mountain road and down to the end of Johnson Road. To get there, we’d take a left on the dirt road rather than going back to the paved road and mailboxes. If we were walking, my dad liked to take what he called a short cut, through the woods and up a steep mountain that didn’t even have a foot trail. His long legs could handle the two mile uphill hike, which is why he called it a short cut. I learned to catch up; a stranger overhearing us talk would have thought my name was “Come on.” When he yelled too loudly or angrily, he would correct himself and smile and play and say, “Kechup! Like you put on your hamburger. Catch up!”

Bill and Jean Ioup lived on the top of that mountain with their three kids. They had electricity and running water and indoor plumbing, but also had an outhouse that had been built better than ours therefore was free from wasps. It also fed a septic tank, which allowed bacteria to decompose the waste, and for the water to filter to plants under ground, keeping them healthy even with the same type of flies that buzzed around our outhouse.

Bill had been a computer programer, with a degree from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, MIT, which I knew must have been important because of how people talked about it, and Bill, with a combination of respect and awe. His brother had also graduated from MIT, and was a respected physics professor in New Orleans who did research for NASA space programs. The Ioups never mentioned their background; they were more interested in raising their children to be happy and healthy, taking care of their chickens, goats, and bees, weeding their garden (it only had vegetables), and brewing beer. In their free time – which was surprisingly often – they played music and hosted parties for all 506 people in Alread Arkansas.

Not all of the people in Alread were as educated and kind as the Ioups. Many were involved in illegal lifestyles, and used the remote location to remain hidden. They probably weren’t included in the 506 people of Alread’s roadside sign. No one judged them, because we all wanted to get along at parties. They had a lot of parties. It was sex, drugs, and rock and roll, but instead of rock and roll, people played folk music and bluegrass with flutes and banjos, listened to country music on AM radio, or ocassionally dusted off an 8-track cassette of Fleetwood Mac or Led Zeplin. The sex and drugs didn’t change; I saw a lot of both.

People moved to Alread to have land and quiet, or to not be bothered by police. They were all kind people, usually stoned, and I learned to laugh with them at their jokes. I learned that “counterfeiting money” was easily confused with “laundering money” because to make counterfeit paper money feel like real linen money after you put it in a clothes drier for ten minutes. They thought that was hilarious, but, as I said, they were stoned most of the time. I already knew about sinsemilla marijuana being sans semillia, without seeds, but no one laughed with me about that, so I learned to keep silent in Arkansas, just like in Louisiana, though for different reasons. Blissfully, I didn’t have to lie about my dad’s garden, because it seemed that everyone in Alread already knew. In fact, my dad had become a respected member of society because of his acres of evil weed.

We visited Bill and Jean and their kids often. I played with their oldest daughter. She was my age, but knew how to milk goats much better than I did. She taught me how to mild goats, and tend bees, and can tomatoes. She was sweet and kind and generous with her time and knowledge, which told you a lot about Bill and Jean, especially in Alread Arkansas. They were role models, and even the money launderers viewed them respectfully, and say “yes ma’am” to Jean, and “yes sir” to Bill, though neither of them spoke often. They usually smiled, though, and they touched each other gently and lovingly occasionally, absent mindedly, which made it that much sweeter.

They usually gave us a bottle of milk, or a mason jar filled with honey, and we’d carry it back down the mountain to be used quickly. We didn’t have electricity, so we didn’t have a way to keep food cold. Dairy products would spoil within a day in summer heat, unless it was government issued butter and cheese – that would last all summer.

We could keep milk or eggs for a few days in Archie Creek, but that was risky so we tried to use it within the first day. Besides, we were usually hungry when there wasn’t enough rain to grow vegetables, and the creek dried up so much that predators ate all the fish from small puddles that were fed by springs as water tunneled down the mountains into our valley.

My dad taught me to share the milk; the first person awake could put it on cereal, if they left some in the bowl for the next person. He liked that plan because he was the first awake. He didn’t empathize easily, I learned when I ate before him once. He saw pieces of cereal floating in the milk and yelled, “I can’t eat that shit after you left shit in it!” He pushed the bowl at me and spun around so that he could walk away from me and the bowl of milk with a few pieces of cereal floating in it. His boots echoed on the wooden floor as he marched away, mumbling about how shitty things were that day. I had a second bowl of cereal; I always enjoyed cereal, even in goat milk, and I had been hungry for a few days.

He had many ups and downs in a day, like our path up and down the mountain to get milk, and I learned to never eat before him again. He was happy and having fun, but he was still Edward Partin, and prone to unpredictable bursts of anger. On our drive to Arkansas, Stevie Nicks sang:

“Thunder only happens when it’s raining

Players only love you when they’re playing ,”

so I learned to avoid the thunder by playing.

He tried living off the land, at first. He sowed the soil, and grew fruit trees and vegetable plants. We hunted and fished for protein. I could catch dinner 100 feet from our front door, and shoot squirels from our front porch. He kept several rifles handy, and would shoot deer from our porch with his .307 rifle. His rifle was much more powerful than my tiny .22; the .307 bullets were as long as my dad’s finger, and the sound of him shooting echoed through the valley. A .307 bullet is almost the same as a Russian AK-47 assault rifle, and it would kill deer from a hundred yards a way. He was an excellent shot, and taught me to ensure that when I shot an animal it died instantly, and didn’t suffer. He was moody, and unpredictable, but deep down he was a good man who didn’t want things to suffer.

We’d walk from the porch to get the deer in the field, they were usually near the tree line, at the base of the mountain behind us. We’d use a knife to quickly field dress the deer, slicing open its belly to dump out the organs we wouldn’t use. Even then, it was heavy, and even my dad was breathing hard as he carried it back to our cabin. We’d hang it upside down to finish bleeding and remove any of the guts we missed in the field dressing. In winter, we could freeze animals outside. In fall, we would cut it into portions, split it between backpacks, and hike up the mountain to take it to Bill and Jean and their freezer. We’d share the meat, which was usually enough for two families for a couple of months. In the winter, when we didn’t have vegetables in the garden, we’d hike up the mountain and through the snow to have venison stew and homemade beer with the Ioups. My dad would give me the last few sips from his beer, which was mostly sweet yeast at the bottom of Bill’s bottle-conditioned homebrew, and it contrasted perfectly with the bitter, robust, wild taste of venison stew.

I’m glad he was such an excellent shot, because he made unwise choices when he took me hunting. Before he built deer stands in trees, and learned to seed forests in front of his stand with grass, we simply walked through woods, silently, looking for deer or wild pigs or goats. Sometimes, he’d have us walk towards each other, staring 100 yards apart and narrowing the gap so that we’d scare deer toward one or the other of us. If you were lucky, you’d be the one shooting towards the other person, who was trying to be silent and hidden as you approached each other; hunting with my dad prepared me for combat more than army training, and it led to my lifelong love of cooking.

Ed Junior didn’t enjoy cooking; he was happy eating a can of chili or a few Turtle candy bars. I missed the home cooked meals from Auntie Lo and my Cajun neighbors, so I took matters into my own hands and began to cook our meals when I was 8 or 9 years old. I had a few library books to help, but mostly I had fun learning through trial and error. No teachers graded me in Arkansas, which probably helped learn to love learning independently.

I’d build a fire in the outdoor pit between our cabin and the creek, using wood I had chopped and dried earlier in the season. I’d walk through the vegetable garden, picking corn or potatoes or beans, looking for ripe ears of corn that had holes from worm; the grubs make great fishing bait. I’d put a grub on a hook, and throw the fishing line into Archie Creek. By the time I had caught a few fish, the fire would have enough coals to cook without smoke. I’d put a grill over some coals, sprinkle the vegetables with oil and seasoning, and let them sizzle on the grill as I prepared the fish.

I’d gut and clean the it, placing their guts in handmade crawfish and snake traps. We’d use crawfish as fish bait; or, if lucky, we’d catch enough crawfish to have a few for dinner. Usually, we’d use crawfish as live bait for bigger fish. My dad taught me how to put a hook through their tail, so they would walk around under water, and to use a metal sinker two feet from the hook so that they could only walk in a small circle. I’d use my fishing rod to throw the hooked crawfish into the deepest part of Archie Creek, a 15 minute walk from our cabin, where we kept the canoe. Large brown bass loved seeing an easy target, and they hit the crawfish with enough force to yank the tip of my rod towards the water. They would fight and flop out of the water, trying to throw the hook, and my heart beat with the thrill of sensing tension in the line and ensuring there was never enough slack for the fish to spit out the hook, but never so much tension that the line broke from the force of their fight. The essence of fishing is finding the right balance between tension and relaxation, and it was my favorite thing to do.

Even when I had caught enough fish for dinner, I would practice catching and releasing fish. Without needing dinner, I was free to practice aiming the bait to exact spots under tree branches, or on the far side of a large boulder with a calm pool in front of it, where fish would lurk, waiting for smaller fish to get caught in the current. I became good, and fish feared me, I liked to imagine.

Fish were the easiest source of protein to catch, so I can see why Jesus fed a lot of people with them. My dad bragged about my fishing skills to his friends and neighbors. Like all nice adults, they supported a kid’s interest and shared learning opportunities. My trips to Arkansas included impromptu cooking lessons from Jean Ioup, who loved cooking healthily for her family. Her daughter and I would pick vegetables from their garden, and I’d try to catch fish in their pond, which had been dug by the Johnson’s bulldozer. People on top of the mountain didn’t have our Archie Creek. They had electricity, but they had to dig wells and ponds. We were lucky. I’m pretty sure that not having television contributed as much to my education in Arkansas as not having teachers.

Being patient was the hardest part about grilling fish. They were small and their meat was fragile, so less effort worked best. If you flipped them too often, the meat would fall off or stick to the grill, and you’d loose your dinner. When you worked hard to catch your fish, you worked hard to keep them from sticking to the grill or falling into the coals.

I placed a metal grill across two river stones and grilled the fish over high heat, quickly and simply, with a touch of salt and pepper. That choice was easy – we only had salt and pepper. If lemons or peaches were in season, I’d pick one from the fruit trees near our fire pit and squeeze the juice over the fish as they cooked. I learned that from a chef I had seen on public television at Uncle Bob’s house. That Cajun chef would say, “oooh weee! D’at some nice fish d’er. I’m gonna put some mo’ lemon on d’er, just afta’ I drink me some mo’ of d’is wine” as he’d drink wine and only turn a fish once, and at the right time, mon ami. So maybe I did learn from television; the months in Arkansas let me apply it. I’d practice and improve and think deeply about what I was learning.

I’d seek out wild herbs and berries when I camped by myself, usually near the canoe and large fishing hole. Instead of a metal grill, I’d soak thin branches in the creek and weave them into a fire-resistent grill. Or, I’d heat up rocks and cook on them. Or I’d try this, or that, or anything that I imagined. There were no external limitations to what I wanted to do. To me, this was freedom. I was more than Huckleberry Finn, I was the invincible son of Edward, and the grandson of Big Daddy, and I had been trained by Pa Pa. I was awesome, in Alread Arkansas.

I loved nature, and the fun of figuring out how to be comfortable in challenging conditions. My dad let me go camping by myself, and I’d bring only a knife, matches, machete, blanket, and fishing rod. I’d catch crawfish and fish, build fires, and find wild berries. I tried carving spears and bows and arrows using a book Granny had given me about a 15 year old boy who ran away and lived in the woods, My Side of the Mountain. He wrote about how he learned to catch animals, and he even included drawings of a figure-4 deadfall for a deer, and a rope snare for a rabbit. He also wrote about how to make emergency fish hooks and string, so I practiced that even though I had fishing hooks inside of my knife’s hollow handle.

I already knew how to trap raccoons, thanks to my dad telling me stories about Billy, and I got to practice on my own. Both books were in first person, so felt as if I were reading an older friend’s guidance, which was nice, because I was 8 or 9 years old and there weren’t other kids in the valley. There wasn’t anyone in the valley, of any age, except my dad, some horses, and a few chickens. Occasionally, a guy named George came for a weekend and slept in a tree house on his ten acres of land next to ours. Sometimes, we’d play cards together, or I’d practice magic tricks with him, but mostly I was alone and read books by older kids, and learned from them.

One of the more obvious scars from this time is on top of my left first finger. I was hopping across rocks that poked through the rapids of Archie Creek when I slipped, losing control of my machete. It sliced the flesh off the bone of my finger, and I had to hold my machete under my left arm on the way back to our cabin because my right hand was trying to cover my left hand and stop the bleeding. My dad was stoned, but wise enough to wrap my finger in a piece of shirt and use duct tape to wrap a stick under my hand, keeping the finger straight. I was upset that I couldn’t ride Indian for a few weeks. I was too young to complain about healthcare access for kids whose dad taught them to play with machetes on slippery rocks.

My dad bought horses his second or third year in Arkansas. His was a golden brown Quarter Horse, and mine was a white Appaloosas with rust colored spots. I named her Indian because I thought the rust colored patches were like the skin color of Native Americans. I had everything one would want, a pony and a 22, like frontier kids in the books I read. rode Indian deep into the wilderness on hunting and camping trips. I could fire rifles from the saddle because my dad had trained our horses to not jump when they heard a gunshot next to their ears.

Horses are terrified when there’s a risk of breaking their leg, and my dad would pit that fear agains their fear of gunshots by leading them into the creek, where four feet of water rushed over their legs as they balanced on irregular and slippery stones. He’d fire a gun again and again and again, until the horses were exhausted from tensing against the gun and trying to stay still as they balanced on the rocks.

He had a couple of other horses over the years, and would “break them” for riding using the same technique. He killed two birds with one shot; I learned to ride a horse in Archie Creek. He would pick me up, screaming and crying in fear, and place me in the saddle, breaking both me and the horse. Maybe that’s why Indian and I were so close: we shared a bond of having been broken in Archie Creek.

Like with Anne, my love for Indian shaped my relationship with my dad, and remind me of how helpless I was to protect things I loved from pain. He would shout and curse at the horses, and would beat them when he lost his temper. It wasn’t often, but it was unpredictable, therefore there was always tension. I recalled a WWII story about Americans defending themselves with rocks after they had run out of bullets and only had a few hand gernades to throw. For a week, they threw one gernade for every ten rocks; to the Japanese, each through looked the same, and each thud sounded the same, so they jumped back into their holes with the same reliability as if things were always exploding. It was safer that way, and their battle fatigue was just as real as the few grenades that exploded after a dozen rocks had not. The lesson of the story, in that book, was to never give up. Throw rocks, if you had to, just never surrender.

Once, when the day had been going well, he was breaking a young filly by tying her to a fence post so tightly that her head couldn’t move. In theory, they can’t kick without pushing their head down first, but no one told her that and she kicked him so hard that he flew at least ten feet through the air. Horseshoes are supposed to be lucky, but not this time; two horseshoe shaped bruises were already forming on his chest, and he probably had a cracked rip or two. He got up, gasping for breath, and cradled his ribs with his one hand and threw fist-sized rocks at her with all of the strength in his other hand. My dad was a strong man, and she jolted from every hit. Her eyes were terrified, and I thought she was looking at me, asking for help. I watched, not knowing what to do. I couldn’t stand between my dad and anything he wanted to do, so I cringed every time he picked up a rock, and my body tightened every time I heard a thud against our horse, even though none of his throws were directed at me.

Back in Baton Rouge, I went to the library and looked up books about kids and horses; I must have read The Black Stallion Returns a dozen times before I returned to Arkansas that winter. But don’t ask me questions about it – I still couldn’t talk about what I read. I learned a little about training horses compassionately, and imagined a lot about living free from worry. The Black Stallion was about freedom.

My dad is a singularly-focused man, without much empathy or understanding of other perspectives. He had moved to Arkansas in his mid-twenties, the same age Debbie had been diagnosed with schizophrenia. His behavior is often described or labeled as bipolar, manic depressive, and intemperate, though court records never said that. He also exhibits traits labeled as Aspergers, being singularly focused, and not having empathy for the feelings of other people. People had told me that Big Daddy was like that, too. Debbie was high on the spectrum, so she was on government disability checks. My dad may have been lower on the spectrum, so he would have been considered odd, rebellious, or intimidating; our government doesn’t financially support someone for being rebellious and intimidating, unless you count the military as government support for rebellious and intimidating teenagers, like my grandfather and many of my dad’s friends who had been drafted and shipped to war in Vietnam. Or, he had PTSD from growing up with Big Daddy, and he reacted mindlessly when challenged or threatened or kicked by a horse or left with a bowl of slightly used milk in the morning.

Though the war had been over for four years, he was still angry about it. He was angry about a lot of things, which was hidden by daily marijuana use; it can be calming. Today, we call that “self medicating,” though at the time people called it being a drugged out hippie.

I don’t remember him ever not being stoned, even though he always claimed that he felt fine. Today, we have enough research to know that marijuana is harmless for most people, or at least the CBD and THC components are. CBD is even used as therapy for some people with mental illness, but without medical supervision it can aggravate the symptoms of schizophrenia. I believe it harmed my dad, and impacted me, and therefore impacted Wendy. It definitely harmed Anne and Indian and Chickadee, the one-eyed chicken.

I kept a pet chicken in Arkansas named Chickadee. That sweet bird was a runt, picked on by other chickens. She had lost an eye in a fight. You’d be surprised at how fierce chickens can be when they fight. But not Chickadee; she was a sweet bird.

Chickadee followed me around as I looked for grubs to go fishing. I’d share the grubs, and eventually trusted me enough to swim to me when I was playing in the creek. I loved that bird, and was unsure how to handle my conflicting emotions when we ate her. She had topped laying eggs, so my dad killed her, and we made smoothered chicken out of her. We were out of ketchup that year, so all we had was salt and a 5 pound block of government butter to flavor her.

My dad and I were an odd pair. I swam with chickens, and he walked around outdoors naked, thrusting his middle finger to the sky and challenging God, the government, and Ronald Reagan to do something about it. The government was sending planes with infrared cameras, putting toxic flouride in water, and making us go to school, where they even controlled when we could piss.

“Never listen to them!” He told me.

“Live free! Piss when you need to!” He said, to no one.

That’s why I used to get in trouble for walking out of classrooms in Louisiana to piss – he seemed obsessed with the freedom to urinate wherever and whenever he wanted. He would wake up and stand on the porch, naked, and piss into his front yard. He didn’t just do the act, he embraced every moment of his freedom with enthusiasm and appreciation.

On clear sunny days, he would stand on the narrow pedestrian bridge he had built over Archie Creek and wave his middle fingers at the planes he imagined flying overhead, yelling at them in with his mind because his mouth was clamped around a lit joint. He would be naked, with his long hair and penis flowing in the wind. There would usually be a joint in his mouth.

He believed the sun was healthy, so when he wanted to relax he’d lay naked on the bridge to absorb all of the sun’s goodness. After I started puberty and began having acne, he made me get naked in the sun with him. He said it helped the acne on his back. Acne on the back and shoulders ran in our family, and he attributed his decreased acne to time in the sun, and my increased acne to being trapped in school all day. He didn’t seem to know the pattern: acne increases with puberty, and decreases by your early 20’s, regardless if you’re in the sun or not. He attributed his miraculous recovery to the sun.

In all fairness to my dad’s theories about acne, when Wendy paid to have a dermatologist treat the acne on my back and shoulders. The doctor charged her $60, and put me under a UV lamp without a shirt. He didn’t have a joint in his mouth, but he knew that acne is caused by bacteria that grows in a type of skin oil that is excreted during puberty and in times of stress, and UV light kills bacteria. At least my dad’s treatment was free, and we didn’t need to wear clothes.

Most of my dad’s oddness was harmless, but it led to a confused kid who tried his best to adapt from laying naked on a bridge and flipping off airplanes, to sitting under a UV lamp in a doctor’s office discussing proper skin care.

His anger came out about religion. I remember a few times where he let go of his steering wheel to give both middle fingers to the sky, yelling “Fuck you, old man! God damn fuck you!”, challenging God to do something about it if He didn’t like people using the lord’s name in vain. He and Mama Jean had fought about going to church when he was a teenager – he resisted all authority – and he resented that she and my aunts talked about Jesus when he asked them for money. His proof that there was no God was cursing at Him and challenging Him to do something about it, the same way he had proven to me that Santa Claus didn’t exist. In fairness, I never heard God respond, nor saw my dad proven wrong about Santa Claus.

When Ed Junior talked about his childhood, especially the times around when Big Daddy was testifying against Hoffa, or when he was gone all the time with people like Audie Murphy, he would get upset and speak quickly. When he came to a point that sounded mistaken, either didn’t make sense chronologically or was too unusual to seem real, he’d get impatient and point his finger and narrow his eyebrows and angrilly settle the conversation by loudly saying, “You could ask them! Go on! Ask them!”

I learned to not ask questions. I never asked Sonny anything, and I rarely asked anyone anything except about hunting and fishing and living off the land, or how to get to the local library so I could read a book about hunting or fishing or living off the land.

He tried living off the land, at first, and did it well for a couple of years. He says I helped, and I know I worked hard with him. He had a strong work ethic, and was persistent and seemingly tireless. He did whatever he set out to do. But, in times of drought he couldn’t grow vegetables or fruits, and Archie Creek would dry up and not provide fish. During droughts, all animals suffer and do unusual things for food, and our chicken coop was a target for hungry weasels, foxes, snakes, an hawks. There wasn’t money to replace the chickens, and without a garden we went hungry, something hard to imagine in America but surprisingly common; 40 million kids go hungry or malnourished in one of history’s wealthiest countries, despite an abundance of ketchup.

We’d hike up the mountain and hitchhike to Clinton to collect government blocks of cheese and butter. He had applied for food stamps while I was in Baton Rouge, and hated sucking from the government’s tit, but he hated being hungry and not having food for his son more. Once a month we’d pick a 5 pound block of government cheese and a 5 pound block of government butter, then use our food stamps to buy canned foods and other things that didn’t require refrigeration. Government cheese and butter doesn’t need refrigeration; it would have made a stronger building material than the rocks we used for our fireplace.

In summer, we’d almost always have potatoes, and had become so used to them that we even bought them with food stamps during the winter. The cabin had simple logs as walls and a simple iron stove in his bedroom; canned goods would freeze overnight, and the freeze/thaw cycles made everything taste like mush, so potatoes were a treat, even in winter.

We’d cook potatoes that butter and saturate them with salt and ketchup. It was delicious, and I’d brag to my friends back in Louisiana that my dad let me eat nothing but French fried potatoes for weeks at a time. I omitted a few parts, like being hungry, and I’d emphasize things like how I had become such a good shot with my 22 rifle that I used it instead of a shotgun to kill rabbits, squirrels, and ducks. When I was lucky enough to see one, we’d cook it on the wood burning stove, slow cooked in government butter like Grandma Foster’s smothered chicken.

I’m proud of how I shot and retrieved the first duck I killed in Arkansas. Two of them had landed in the widest section of Archie Creek, where we kept our canoe. I pulled my hand from my pocket, which carried the hand warmer Pa Pa had given me for Christmas many years before, and I shot it from 20 yards away. That accuracy with a rifle is remarkable for anyone, especially a ten year old kid.

The duck died instantly. The other one flew away, but returned and landed next to its mate and floated with it downstream, towards the rapids. I paused for a moment, sad, realizing that I had separated the two. I was surprised that I felt sad, and I paused for a moment to try to understand why I was sad. I didn’t complete that thought because my mind began imagining how happy my dad would be with two ducks for dinner instead of just one, so I reloaded my single shot rifle and aimed again. I missed, which was rare for me,

The male duck floated in the middle of the widest part of the creek and was drifting towards the narrow and rocky rapids. I would loose him if I didn’t do something quickly. We had lost Anne by then, so she couldn’t retrieve it, and our canoe was on the other side of the creek, so I began to undress. I stood on the shore naked, and took a deep breath. I exhaled slowly before doing what I felt must be done.

I tossed a few rocks onto the ice near shore, where water moved more slowly, and broke enough open to wade into the faster and deeper portions. It was so cold that my testicles jumped into my stomach and I couldn’t breathe, but I focused on saving our dinner before it was lost to rapids, and I began breathing again, slowly, and in gasps, as I waded in water up to my rigid nipples.

I couldn’t reach bottom for the last few yards, so I had to swim and catch up with the duck as it headed towards the rapids. I grabbed it with my left hand, and swam back with my stronger right hand. The current was taking me towards the rapids, so I tried to swim across the current as quickly as possible. Even so, I had drifted past the breaks in ice. I approached shore and had to reach into the water, by my feat, to grab rocks and throw them onto the ice to break a path.

It took three or four rocks to break a small path towards shore. I moved forward slowly, and when the ice became too thick to break near the slower moving water near shore, I crawled on top of it with the duck still held high in my left hand and I finally began to notice the cold as I pulled my naked body across the ice with my right hand. I couldn’t stand up on the slippery ice, so I pulled myself onto shore and stood up on solid ground.

I walked back upstream to find my pile of clothes and .22 rifle, redressed, and ran home, shivering but not mindful of the cold because I was focused on my excitement. I was at least a year older than the last time my dad had thrown me past the ice with a bottle of peppermint soap, so I was old enough to realize that the cold was the same, but the suffering was less, because I was choosing to do this. I’m lucky; most adults don’t realize that everything’s a choice, but I realized it at a young age.

My dad was proud of me, and he kept saying so, but his mood was still dark. We cooked the duck in what must have been a pound of butter and sat around the wood stove eating it with the last of our ketchup. He kept looking at his plate, apologizing for not being able to provide a better Christmas dinner for his son. He spoke of me as if I weren’t there. He gave me a few gifts, meticulously and lovingly wrapped in pieces of a brown paper bag, which meant he had done it before I was there that winter. I appreciated that he had been thinking of me while I was in Baton Rouge.

He had wrapped a rattlesnake rattle for me. It was one we had killed and eaten in the summer. I counted 13 rattles; it had been an average sized snake. He also wrapped a Turtle candy, like the one we had falling off the cliff a few years before, he reminded me. I joked that it tasted better than the rattlesnake. The final gift was a pocketknife, one he had used when he was a kid a few years before, which was wonderful because I had lost the knife Pa Pa gave me.

I gave him an ashtray I had carved from a stick using my knife, before I lost it. I had heat treated it to be fire resistant, like I had learned in a book about carving spear tips and fire tools in the woods. His final gift was extra special, and I was anxious for him to know that I had thought of him while I was in school, and had asked Wendy to help me buy it. It was a small bottle of his favorite brand of bourbon whiskey, 101 proof Wild Turkey Whiskey. It had cost almost $4; like Billy, the kid in my dad’s stories, I had learned to work odd jobs and save money for things I wanted.

I had earned the money myself, mowing a neighbor’s lawn in Baton Rouge, and I hoped he realized I had listened to him like he had listened to me about Stretch Armstrong. He cried by our wood burning stove as our duck smothered in government butter, and he drank the whiskey that night. He offered me a sip. It burned my mouth, but I swallowed because I knew that strong men drank whiskey.

The next summer, when I returned after a spring semester under the tyranny of teachers, he sold the horses and we hitchhiked across the country with an expensive leather saddle so that he could sell it. He was in a better mood, but had lost weight over the winter and seemed tired.

We hitchhiked to Kansas, sleeping in grasslands that lined the roads and the Kansas turnpike. If he saw an inexpensive all-you-can-eat buffet, we’d stop so he could buy one ticket and sneak food to me. We were caught, and I felt so embarrassed that from that time onward I would claim to not be hungry at restaurants. When we arrived in Kansas, we ate from the generosity of his friends who had bought the saddle.

One of my aunts offered him work, so we hitchhiked from Kansas to Texas, where she lived with her husband and their children. They wanted a gazebo for one of the decks near their swimming pool, and knew my dad was handy with woodworking tools. Uncle Tim was patient, like any good man who loved his wife and tolerated his brother in law. My cousins wanted to play with me, but I didn’t know how to play the way they did. And when they wanted to swim, I didn’t want to because I was embarrassed about my back acne and thin ribs from walking along highways and skipping meals. And I was embarrassed by how Aunt Cynthia and Mamma Jean kept talking about how polite people ate and talked, because they only said it when it was the opposite of what I was doing. I returned to Baton Rouge after that summer confused about where my dad lived. I told everyone that we camped a lot.

He hated the government tit, and he grew tired of being hungry and hitchiking to earn money, so began growing marijuana again. He was wise enough to not grow on his land. The government was watching, he said, so he repeated his methods from Louisiana, and when I returned the following summer I helped him hike through woods and care for his secret gardens, just as we had always done.

He was nervous about government spies, so we took extra caution and tried to hike at night. Arkansas soil isn’t as fertile as Louisiana river silt, so we brought backpacks full of horse manure to mix into the dirt around each marijuana plant. This was one of my only complaints in Arkansas. I knew we didn’t want to leave trails, and horses are big and noisy and leave obvious trails, but I thought it was ridiculous to train horses to carry you yet we were walking into the woods, carrying their poop to feed plants we couldn’t eat. It was as crazy to me as back in Baton Rouge, when Mike and Wendy fertilized their lawn so that we had to mow it more often. Adults never made sense to me.

He had two or three gardens, and they would grow plants that towered over me. The first year, we hiked to the plants carrying backpacks of poop. The next year, which was another drought, was my least favorite year in Arkansas because we hauled heavy buckets of water every day, all summer, dumping the water at the base of a plant and repeating this process for dozens of plants. If the drought killed them, we’d be hungry again. He was determined to keep his plants alive. The hike was at least a mile from Archie Creek, though the boring repetition made it seem much farther. Somehow, it was uphill both ways, and even Bill’s famous physicist brother would have been baffled by my memory of that impossible geography.

My dad was happier with daily work. He seemed to benefit from the focus of having something to do. And he had money again. His jeep had broken down – we had flipped it the year before, rolling down one of the steep mountain drop-offs along Route 1 at night, when he was speeding home and taking corners too quickly. I’m sure a joint was involved, and perhaps a beer.

We had been walking the final two miles to his cabin since then, so one of his first purchases was a new 4X4 Ford truck. He strolled into the Clinton dealership with his long hair mangled past his shoulders, and a thick beard that touched his chest and hid his face. He carried a brown paper bag with $14,700 in used bills, the type you’d get from selling things to people rather than withdrawing them from the bank. He would have smelled like fertilizer and evil weed, and would have been pushy with anyone not doing what he wanted.

I believe he was abrupt with the people working there, and I believe they were terrified, and I believe they deposited the cash before they called the sheriff. We wouldn’t know that for another year. At the time, I was happy to ride up the mountain in a new truck, because I had never grown to enjoy that two mile hike.

His positive mood made him feel like being social, and we used the truck to drive up the mountain and attend more parties at Bill and Jean’s or other farms in Alread. They’d have bands and food and pot for adults, and kids would gather to blow things up with fire crackers. He’d play music with the other adults, smoke joints and drink beer, and tip the bands generously. When times were good, my dad was energetic, positive, and always ready to party. And their kids liked him, because he liked to play and he never asked them about their homework. He said school was useless; he had dropped out of high school, and look at him.

For some reason I never learned, there were lots of single women at these parties. He fucked a lot of them, and when he was fucking one we spent more of our free time up the mountain than in our valley. It was fun. We’d hike as a group to hidden swimming holes and waterfalls, and everyone would get stoned and naked and play in the water. Unlike the Amite River in Louisiana, Arkansas creeks have crystal-clear water, and nothing was left to the imagination. To augment my sexual education, he and his friends let me watch pornography with them on a television powered by a diesel generator; a store in Clinton rented VCR machines and boxes of porn for long weekends, and the generator was far enough away from the house to not be heard as much. It wasn’t nearly as loud as the airplanes that flew over Granny’s house.

There was a different woman in his life every time I visited, so I never tried learning their names. One even took me to Clinton for pizza, and to an amusement park to ride roller coasters. She was around for two visits to Arkansas, one summer and one Christmas, and she planned ahead for Christmas and wrapped presents for me.

All of the women my dad was with seemed nice. A few were overcoming their own challenges; the woman who took me to an amusement park had a five year old boy that was sad because his dad had died. He didn’t know that she had found him hanging by a rope in their bedroom, and had tried to lower him by burning the rope with her cigarette lighter, but hadn’t been quick enough and watched him die. After that, my dad spent more time at her place, helping with her garden at the expense of her own, and yelling at her son to eat his fried green tomatoes. I would watch, and wish that he’d learn to relax, like I had wished for Indian and Anne. Everyone has a story.

All of my dad’s women were kind to me. Many were stoned often, and some were funny without intending to be. One talked about little green men running around the school bus she had converted into a home. They were together only a short time, but they had a child together. Her name was Jessica, and she has the same dark brown eyes as my dad and me, which were the same eyes as Mamma Jean.

At first, Jessica’s mom tried to keep my dad in their life. They would argue as we walked up the mountain to one of their cars. She was pregnant, and would soon have to stay on top of the mountain, perhaps in the broken down school bus that she had made into a home. It had a wood burning stove and little potted plants, and was more spacious than the trailor the Johnson’s used as a laundromat and general store.

It was more like a home than the barn we lived in. We were building a new home with the money my dad had been making selling pot, so we moved into the barn again. She had been one of the women he fucked on top of the pile of lumber. She wanted to list my dad as her baby’s father, but she said that meant the government could ask him for child support.

He said “Fuck them! Let them try!” because he didn’t understand her hints. He didn’t realize she wanted him to help with Jessica’s support; if Wendy had believed she existed, she would have advised her to give up hope, get a job, and to change her name.

She must have exhausted herself, and six months after Jessica was born left Arkansas without telling my dad where they went. I don’t know if the little green men left with them, but they must have because I haven’t seen one since. I have spoken with Jessica, though, and her children have Mamma Jean’s dark brown eyes, though she doesn’t know who Mamma Jean is. She hasn’t noticed any green men, either, so maybe they didn’t leave with her and her mom, whom she loves very much.

My father carried anger inside of him about many things, and he often confused sadness for anger, but losing Jessica was all sadness. It deflated him. I believe he had matured in the 11 years since I was born, and saw my sister as the helpless baby she was, but without Big Daddy to pay for her daycare or Mr. White to play with her. He was unable to control his emotions around Jessica’s mom, which is why she fled when her daughter was six months old, the same age as I was when Wendy fled Louisiana.

Jessica’s mom fled with her in the mid 1980’s, a few years after President Ronald Regan’s War on Drugs had begun. The evangelical Christians who funded him wanted to rid America of drugs and unwed fornication, two of my dad’s favorite activities. They changed America forever, because you spread beliefs in a democracy by funding candidates.

Regan believed in trickle down economics, that by supporting the top percent of tax payers they would find ways to support the lower majority. His administration cut back social services, and claimed things like ketchup was a vegetable in school lunches. I would be one of the kids with a lunchtime badge that let me eat a free lunch, and let everyone know I was eating a free lunch. Fortunately, there was plenty of ketchup to keep me healthy; it’s a vegetable, we were told by the politicians who didn’t want us smoking weed or fucking. But, unfortunately, the office that gave us 5 pound blocks of butter and cheese closed, and I never received more from the trickle down economy that was known as Reagan-omics.

My dad was wrong about most of his government theories, but he was right about airplanes with infrared cameras. Marijuana releases more heat than most plants, so a garden is easy to spot with infrared cameras that can see heat radiating, like how a rattlesnake sees mice and other warm-blooded rodents hiding in weeds. The airplanes and cameras were funded by the War on Drugs. To pay for the war, the Reagan administration used creative funding, like they used for the the Iran-Contra scandal, providing weapons to Iraqis fighting Iranians. Those weapons were paid for by illegal actions in Nicaragua, the Contra rebels, and the War on Drugs was paid for by unconstitutional conflicts of interest in America.

In the War on Drugs, money or property seized from a drug dealer would be equally divided among the prosecuting district attorney, the judge, and the arresting officers. That payment scheme motivated local sherifs to deputize local men and seek out people growing what evangelical Christians believed was an evil weed.

It turns out that my dad was correct about deputies hiding in the woods. We didn’t know it, but the sheriff had obtained search warrants and money for hiring deputies because of my dad’s brown bag of cash at the Ford dealership. Without knowing that, we were confused by inconsistencies in the woods around us. We didn’t talk about it, and I only mentioned hearing footsteps once. In hindsight, it’s funny to have been right.

I noticed evidence of humans walking in the otherwise empty woods, because when you live off the land your senses are more observant. You notice more. You know what’s natural, and what’s not. I told my dad that I heard people walking at night – there’s a subtle difference between natural pops and cracks of branches at night due to fluctuating temperatures and decomposing plants, and the sound of four-legged animals walking compared to the sound of two feet successfully being silent every few steps. I lost sleep a few times, wondering if my imagination were too wild, or if I had read too many fiction books.

To make things worse, I added to my dad’s paranoia because I was a dumb kid. I had stolen a small pistol in Baton Rouge, a two-shot Derringer that could be concealed in one hand. I wanted to use it in Arkansas, so when one of my dad’s friends visited with his son I hid the pistol in woods near a fishing hole and pretended to find it. We showed it to our dads, expecting them to congratulate our good luck and let us play with it. Instead, they discussed who left it, why the serial number was filed off, and what to do with it. In the end, my dad took it to the sheriff’s office, slammed it on the receptionist’s desk, and told them to stop trying to frame him. I’m sure he cursed a bit, and I’m sure he was thinking about all of the attempted framing of our family and Hoffa, and I’m sure the receptionist was terrified, but it never showed up in court as evidence. That would have been hilarious – to track the gun down to Baton Rouge, and to compare me to my grandfather stealing all the guns in Woodville Mississippi; he would have thought a single, tiny pistol wasn’t worth people getting upset at me.

All of these things added up to an arrest warrant for my dad. When I was 12 years old, the same age my dad had been when his father went to prison the first time, the sheriff and deputies surrounded our house while we were working inside. The walls were up, and we were inside, cutting strips of wood to line the windows and doors; the walls were red cedar, and my dad wanted to line the openings with black walnut.

We were cutting thin strips from long pieces of lumber on a diesel powered table saw, like the one he used to watch pornography. We had been working inside for hours, and he was covered in sweat and sawdust, which stuck to the hair on his shirtless chest. I was sweating, too, and sawdust stuck to my wet shirt – I didn’t have a hairy chest at 12.

My ears were ringing from the sound of the table saw, which is why I didn’t hear the jeeps and trucks that had been surrounding our home, the groups of men getting out their guns and wondering why we hadn’t responded to their calls to step outside.

He turned off the table saw to take a break, heard the men, and put on a shirt to step outside. There were approximately twenty armed men carrying shotguns and rifles; some were pointed at us. A few wore pistols holstered on their belts, but I only saw two with badges. They had been appointed by the sheriff to catch what they believed were dangerous drug dealers – the angry guy with the hair and the beard, and his 12 year old son. The deputies, who must not have had other jobs or anything else to do, searched our property while my dad stood next to me, in handcuffs.

The deputies proudly displayed a mechanical scale they found. My dad used to weigh bags of marijuana. It was a nice one, with sliding weights to read the weight on balance arms, like one a scientist or jeweler would use. Only drug dealers had scales like that in Alread Arkansas.

They scraped together two pounds of waste weed from the cracks of his barn. It wasn’t even good enough to be called shake, the worst grate of weed. It was what wasn’t worth sweeping up from the cracks, even for my dad, who smoked daily, but they scraped together enough of the evil weed in the cracks of his barn to convict him of “cultivating a controlled substance.” The newspapers celebrated the local sherif for confiscating illegal marijuana and drug paraphernalia valued at over $20,000 on the streets. Even if Alread Arkansas had a street value for pot, I can’t imagine anyone taking the time to sort through the rat turds in what they confiscated from my dad during the War on Drugs.

Before my dad became an example for America – he would serve almost two years in federal prison – the deputies confiscated my suitcase from Louisiana and went through it. One was curious about the fake fingers and handkerchiefs. Another thought he found a bag of cocaine in my bag and brought it to the sheriff, who asked my dad what it was. He didn’t know, which I thought was funny thing not to know if you were a policeman. I told them it was finger-printing powder, part of a kit I brought to practice being a detective. I had read a book that suggested making finger printing powder chalk dust, like the white chalk my teachers used on boards at school.

He looked down at the bag of white powder, back up at me, then over to my dad. I got my kit and showed them the camel hair brush to apply powder (it was one of Uncle Bob’s camera lens brushes), wide clear tape to pick up the dusted fingerprint, and index cards to fix the tape and label the fingerprint. He didn’t ask about the fake fingers, but I told him anyway. The fake fingers were from a magic shop. You could hide the thin silk hankercheifs in them and pretend you made things disappear. I had seen Mohamed Ali do that for Fidel Castro, on television. He exposed the fake finger, because his religion didn’t allow him to lie. My grandfather knew Fidel Castro and President Kennedy, I wanted to say, hoping it would help our situation.

The sheriff didn’t know what to do about this. Or he didn’t understand me because I spoke so quickly. Either way, he gave me the plastic baggy of white power and went back to arresting my dad as I collected my fake fingers and silk handkerchiefs.

The deputies put him in the front seat of the sheriff’s truck, and placed me on his lap. We drove through Archie Creek, two miles uphill, and three more miles to Bill and Jean’s house. They dropped me off, and my dad went to jail for the second or third time.

For the next week, I played in the woods by myself, using Big Daddy’s knife to keep my mind preoccupied with building emergency shelters, rabbit snares, and deer deadfalls. I fished in a small pond on Bill’s land. It wasn’t as fun as the Archie Creek – you just sat on the shore and waited for a small fish to bite the cricket on your hook – but it kept me busy. After a week of this, my dad was released on bail.

One of his friends picked him up in Clinton and dropped him off at Bill and Jean’s to meet me. He was crying as he got on his knees and hugged me for what seemed like several minutes. He pulled away, wiped his eyes, and apologized for being a fuck up. I told him that I loved him, and it wouldn’t matter if he blew up the world I’d still love him. He started crying again and said, “I’m not that kind of person…” before trailing off to his own thoughts and understandably self-centered tears. For all of his life, he tried his best to be a good person, to overcome demons he didn’t know he even had, and being arrested with me and being unable to care for me was his awakening that perceptions mattered.

We didn’t talk much on the eight hour drive back to Baton Rouge. He dropped me off, and immediately returned for his trial. He was sentenced to two years in federal prison. The War on Drugs also increased jail sentencing times as a deterrent that no one was aware of. I’m unsure of the exact dates, and the alternating between state and federal jails, but I remember the ride on his lap, and know that my life had changed courses again.

Because of how the Regan administration funding local law enforcement, my dad lost his truck and possessions. The sheriff’s office kept his truck, citing that it was used to carry drugs therefore was theirs under the War on Drugs laws. He fought them from keeping his property, winning because of a technicality, but he had to sell it when he got out of prison because he had no other way to earn a living. During these couple of years, I lived in Baton Rouge full time, and began my transition into teenage years with Wendy.

He’s a hard man to love, but he wasn’t as lucky as I was. He had gone threw a lot, and didn’t have responsible people in his life when he entered his 20’s. He didn’t have a Wendy, Debbie, Granny, Uncle Bob, Auntie Lo, Pa Pa, Ma Ma, Keith, or Bryan in his life when his dad went to jail the first time, when he was 12, like I was when he became a convicted drug dealer in federal prison. He didn’t have an Anne or an Indian to love, and he didn’t have the people who entered my life when he left it for a few years.

He went to federal prison, lost his legal right to own a gun, and lost his right to vote. He had to sell his land because twenty unemployed men with temporary deputy badges found a few ounces low quality shake in the cracks of his barn floor. His two pounds of shake and rat turds wouldn’t get you nearly as high as seeing Stevie Nicks dance at a Fleetwood Mac concert. I should know. I was there. It was a wonderful show, and I was high on my dad’s shoulders. You could ask them.

Return to the Table of Contents.