Bid Daddy and Jimmy Hoffa

1940’s – 1972

What Big Daddy and Uncle Doug had done in Woodville Mississippi was being repeated on a larger scale nationally. Crime and labor unions were unifying in the prosperity and opportunities that followed WWII. Politicians and presidents and gangsters were promising to make every man a king. One of those people was James “Jimmy” Hoffa, president of the national Teamsters union.

Hoffa wasn’t a large man, but he surrounded himself by former boxers, soldiers, and football players who could influence or intimidate their way into national trucking contracts. They grew the union to millions of members. Those millions of men paid dues each month, in cash. Hoffa had access to millions of dollars hidden from the government. This cash attracted the attention of organized crime, especially the Las Vegas mafia.

Hoffa lent millions of dollars to build casinos. In return, the Teamsters were awarded contracts to move construction materials across the country. Sometimes the trucks arrived with material still in them, and sometimes they included guns and piles of cash. Soon, Teamster trucks were loading guns and drugs in the ports of Miami and New Orleans to feed the growth of organized crime in America.

Hoffa became friends with Hollywood, too. Every movie set was transported by Teamsters; the next time you watch movie credits, wait until the end and notice the large Teamsters logo, the wagon wheel and horses, and you’ll see how far their influence reached.

The biggest threat to America wasn’t Teamster gangster money, it was the Teamsters themselves. There were 2.3 million Teamsters registered in America by the 1950’s, and the American economy would collapse without ways to ship products to each other If Hoffa called for a national strike. The Kennedys wanted to stop him.

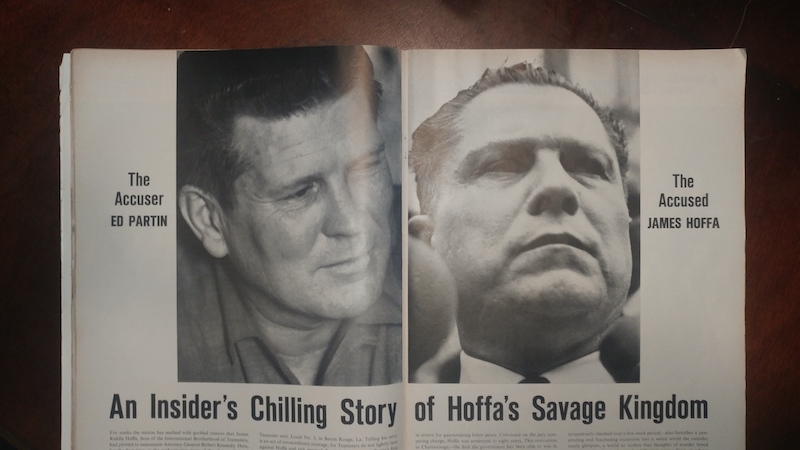

Robert Kennedy had become the United States attorney general when his brother was president. His election platform was based on stopping our government from being influenced by organized crime and the Teamsters. His feud with Hoffa became known as the Blood Feud, and historians have said that almost everyone in America knew about Hoffa and the Blood Feud in the 50’s and 60’s, and they’d soon learn about Ed Partin.

Big Daddy was 26 in the early 50’s. He had started a family with Mamma Jean, though she was called Norma Jean then. They had met in 1949, when he was still in Woodville. She was a beautiful 18 year old young woman, with eyes so dark and brown that they almost looked black. Her red hair was always meticulously and tastefully styled, and her smile was subtle, like Big Daddy’s, but hers made her seem mature, not playful, like a wise and confident young lady.

She loved her family, Jesus, and catfish. She told me that she invited her first suitor to meet her parents for dinner. He was a handsome and successful and polite gentleman from her church, but he didn’t like catfish so she had to let him go. She met Big Daddy, who smiled and spoke gently and politely asked for second and third helpings of her cooking.

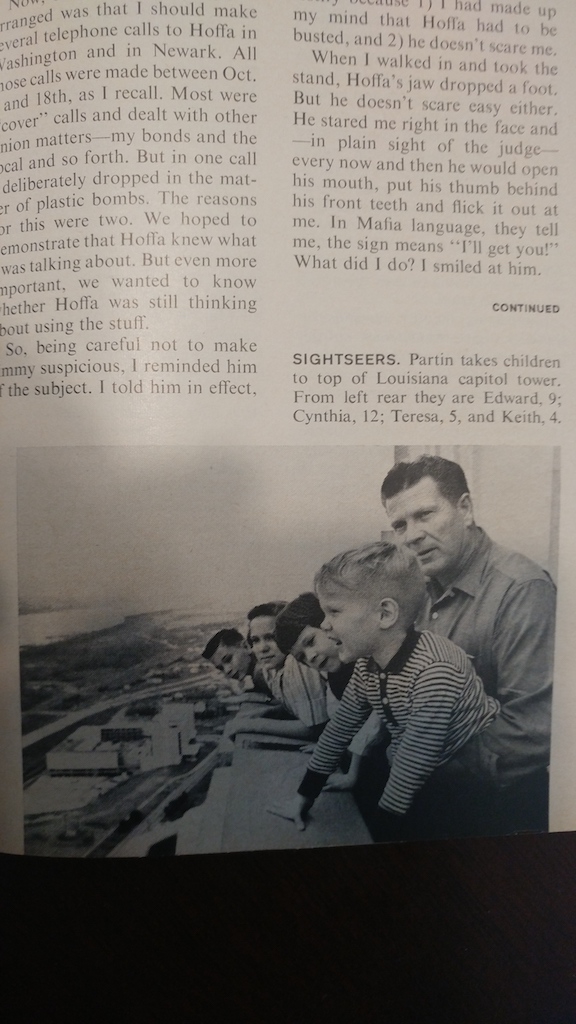

Mamma Jean knew Big Daddy was a Teamster, but didn’t know about his criminal history or his illegal activities until after she had children. They moved to Baton Rouge, and had three girls and two boys, Janice, Cynthia, Theresa, Keith, and my dad, Ed Junior. He was born in 1954, the middle of five children. He would be nine years old in 1963, when his father and Hoffa are said to have planned to kill Robert Kennedy.

Her first signs of Big Daddy’s hidden lifestyle began when, as she said, “he stopped coming to church,” as if that were the worse thing he could have done. It wasn’t until Keith was born that she realized the possible extent of his illegal lifestyle, of the mafia and the guns and violence. Almost 40 years later, she explained her perspective in a letter to us, shortly before she passed away.

My dear children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren,

I don’t know how to begin this. I should have written this when you were small, while it was fresh on my mind, also while your daddy was living. After someone dies, you seem to forget all the bad things and remember only the good in them. That is the way it is with my memories of Ed.

He was so charming when I met him. As Jimmy Hoffa wrote in his book, “Ed Partin could charm a snake off a rock.” It was Aug. 1949 and I was living with my sister, Mildred and her husband, Percy Cobb in Natchez, Mississippi. International Paper Company was building a mill and Percy was superintendent of construction. Ed was steward over the Teamsters, Union (I.B.T.C. and W.). He came to the house one afternoon to talk to Percy concerning the Teamsters, and that is how I met him. I was 18 years old and he was 26. I thought he was the most handsome man I had ever seen. He had blond hair, blue eyes and teeth like pearls. Keith, he looked just like you, except he was 6’2”. He didn’t smoke or drink, not even beer, and I believed every word he said. He loved to come over to Mildred’s when I babysat James Paul. I thought he would make a good father. After six weeks we were married in Fayette, Mississippi, Sept. 27, 1949.

Her letter continued to explain things her children would want to know, of why she left Big Daddy and hid the five of them after Keith was born. She didn’t know what to do when her husband came home and collapsed, bleeding from knife and gun wounds, with dozens of thousands of dollars taped around his waist, talking about gun deals with Fidel and the mafia. She had to focus on her children.

America didn’t know it yet, but Big Daddy kept dynamite for Jimmy Hoffa in a house that he had kept secret from his family and the local Teamsters. He would later state that it was part of a plot by Jimmy Hoffa to kill the United States Attorney General. The dynamite and plot were only part of his criminal record. In the mid 1960’s, he went to jail for kidnapping. Robert Kennedy sent men to get him out.

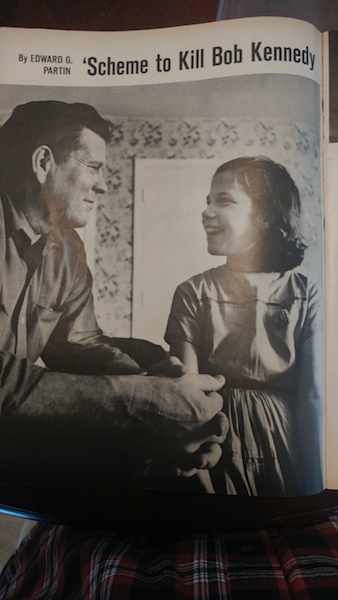

Big Daddy was released from prison within a few days, and his criminal charges disappeared. Kennedy located Mamma Jean and her children, and asked her to reunite with Big Daddy. To convince her, the U.S. government bought her a house and guaranteed her a lifetime monthly paycheck, part of a controversial program of paid informants. Within a month of them settling into a new home, they were showcased across America as the family life behind a Teamster leader.

In the 1960’s, popular national magazines like Life showed photos of them enjoying life in Baton Rouge, and of Big Daddy leading union picket lines for Teamsters. He was shown to be a strong, confident leader for working class America. When the teacher’s union went on strike, even Teamsters carried picket signs for them, with Ed Partin leading the walk. His dishonorable military service was renamed, the rape charges camouflaged, and the other charge spun to portray a man unafraid to do what needed to be done, even in the face of Jimmy Hoffa.

Both Robert and John Kennedy would be assassinated, but not by the Teamsters. In 1964, when my dad was eight years old, President Kennedy was shot while driving through Dallas Texas in a convertible car. The government report mentioned Big Daddy:

During the course of its investigation, the committee also examined a number of areas of information and allegations pertaining to James R. Hoffa and his Teamsters Union and underworld associates. The long and close relationship between Hoffa and powerful leaders of organized crime, his intense dislike of John and Robert Kennedy dating back to their role in the McClellan Senate investigation, together with his other criminal activities, led the committee to conclude that the former Teamsters Union president had the motive, means and opportunity for planning an assassination attempt upon the life of President John F. Kennedy.

The committee found that Hoffa and at least one of his Teamster lieutenants, Edward Partin, apparently did, in fact, discuss the planning of an assassination conspiracy against President Kennedy’s brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, in July or August of 1962. Hoffa’s discussion about such an assassination plan first became known to the Federal Government in September 1962, when Partin informed authorities that he had recently participated in such a discussion with the Teamsters president. The government investigation said:

In October 1962, acting under the orders of Attorney General Kennedy, FBI Director Hoover authorized a detailed polygraph examination of Partin. In the examination, the Bureau concluded that Partin had been truthful in recounting Hoffa’s discussion of a proposed assassination plan. Subsequently, the Justice Department developed further evidence supporting Partin’s disclosures, indicating that Hoffa had spoken about the possibility of assassinating the President’s brother on more than one occasion.

In an interview with the committee, Partin reaffirmed the account of Hoffa’s discussion of a possible assassination plan, and he stated that Hoffa had believed that having the Attorney General murdered would be the most effective way of ending the Federal Government’s intense investigation of the Teamsters and organized crime. Partin further told the committee that he suspected that Hoffa may have approached him about the assassination proposal because Hoffa believed him to be close to various figures in Carlos Marcello’s syndicate organization. Partin, a Baton Rouge Teamsters official with a criminal record, was then a leading Teamsters Union official in Louisiana. Partin was also a key Federal witness against Hoffa in the 1964 trial that led to Hoffa’s eventual imprisonment.

While the committee did not uncover evidence that the proposed Hoffa assassination plan ever went beyond its discussion, the committee noted the similarities between the plan discussed by Hoffa in 1962 and the actual events of November 22, 1963. While the committee was aware of the apparent absence of any finalized method or plan during the course of Hoffa’s discussion about assassinating Attorney General Kennedy, he did discuss the possible use of a lone gunman equipped with a rifle with a telescopic sight, the advisability of having the assassination committed somewhere in the South, as well as the potential desirability of having Robert Kennedy shot while riding in a convertible. While the similarities are present, the committee also noted that they were not so unusual as to point ineluctably in a particular direction. President Kennedy himself, in fact, noted that he was vulnerable to rifle fire before his Dallas trip. Nevertheless, references to Hoffa’s discussion about having Kennedy assassinated while riding in a convertible were contained in several Justice Department memoranda received by the Attorney General and FBI Director Hoover in the fall of 1962. Edward Partin told the committee that Hoffa believed that by having Kennedy shot as he rode in a convertible, the origin of the fatal shot or shots would be obscured. The context of Hoffa’s discussion with Partin about an assassination conspiracy further seemed to have been predicated upon the recruitment of an assassin without any identifiable connection to the Teamsters organization or Hoffa himself. Hoffa also spoke of the alternative possibility of having the Attorney General assassinated through the use of some type of plastic explosives.

They discussed it in 1962, and he was assassinated in 1963. The similarities between the plot and the shooting led to many theories, articles, and books questioning if there was more to Kennedy’s assassination. The gunman, Lee Harvey Oswald, had lived in New Orleans, and in the months before shooting President Kennedy he trained with the Baton Rouge civil air patrol under the name Harvey Lee, and state investigators said that before Lee Harvey Oswald shot President Kennedy my grandfather drove him to the New Orleans airport, but a connection between Big Daddy, the Teamsters, and President Kennedy’s assassination couldn’t be proved.

Without more evidence, Hoffa was only charged with jury tampering. My grandfather testified that Hoffa offered $25,000 to one of the jurors, and in court when he was called as as a surprise witness, Hoffa simply said, “Damn. It’s Partin,” though it would have been funnier if he had said, “Damn. It’s Big Daddy.”

Hoffa fought his case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court and lost. He would write an entire chapter of his autobiography about the irony of Kennedy using national media and false versions of Big Daddy to influence the jury that convicted him to 8 years in prison for jury tampering, which he denied was true up until his disappearance in 1975. He would have been frustrated to learn that to this day, the verdict cited by court cases fighting unlawful influence and testimony from paid informants has been the Supreme Court ruling about my grandfather’s testimony in the aptly named Hoffa vs the United States.

Hoffa began his 8 year prison sentence in 1968, when Wendy was 12 years old and my dad was 13. Big Daddy returned to Baton Rouge with his record cleared, and what was perceived as federal immunity from criminal prosecution. The Kennedys assigned federal agents to protect him and our family after someone fired three shotgun blasts through into his hotel window, and after he came home one night with a bullet hole in his stomach. The FBI assumed Teamsters loyal to Hoffa were trying to kill him, or to influence him to change his testimony and free Hoffa. We had protection for the eight years that Hoffa was in prison, until his disappearance when Wendy was 19 and I was 2.

In the years that followed Hoffa’s mysterious disappearance, Big Daddy ran the local Teamsters with the confidence of someone who could not fail. Like Hoffa, he received union dues each month and used the cash as he wished. Newspapers photographed him handing cash to union members not getting paychecks because they were in picket lines, and those same newspapers talked about how he brought jobs to Baton Rouge. He even invested in our home; he built the Baton Rouge International Racecar Speedway, and no one seemed to care that he used materials his Teamsters stole from construction sites all across the state. Stealing was easy for Teamsters, because they simply by not unloading all materials off of their trucks when making deliveries. When work was brought to Baton Rouge, men could stay near their families instead of leaving home to follow work opportunities. Big Daddy got things done for the men in Baton Rouge.

He grew the Teamsters so that they had contracts for every trucking job in Louisiana. He’d begin contract negotiations by asking managers if they’d like to hire union truck drivers, and he’d either be smiling politely, being charming and charismatic, or by standing close to them and not smiling, being silent and intimidating.

When the managers of a lumber company refused because they didn’t need more workers, especially because they could pay African Americans to drive at half the price of union drivers, he and Doug and a few white Teamsters cut down trees so that they blocked the dirt road leading from the forests. When the drivers stopped their trucks to clear the road, they were never seen again. Two messages were sent, one to management, and one to non union drivers.

The next day, Big Daddy returned to management and said, “I understand you have openings for drivers.” He would have been smiling – he could be charming, according to Hoffa and Mamma Jean. Teamsters got that contract, and many more like it. The governor of Louisiana, McKeithen, told the New Orleans Times-Picyune:

“I’m not going to have Partin and a bunch of hoodlums running this state. We have no problems with law-abiding labor. But when gangsters raid a construction project and shoot men up at work I’m going to do something about it.”

Companies had begun arming workers, like ranch owners armed their cowboys to protect herds of cattle in the American Wild West. The incident with Bergerson Construction company was one of the shootouts that made news.

Uncle Doug had followed his big brother from Woodville to Baton Rouge, and was helping him with the Teamsters, and grooming himself for when he would eventually assume leadership. He was a nice guy; though “nice” is a usually an adjective open to interpretation, it fits Doug. He looked like Ed Senior, but was smaller and somehow you knew he was more genuinely kind.

He loved telling stories and teaching, and taught me how to modify shotgun shells to become gernades. You use a razor blade to cut around the plastic slug, where it meets the metal primer, but leave a tiny bit of plastic intact. You want that cut to be weaker than the folded end that retains the shotgun pellets, so that when you shoot the entire shell launches out of the shotgun instead of the small pellets. The slug would knock holes through doors, and would explode on the other side. The door defused energy enough that the explosion rarely killed anyone.

My dad, Ed Junior, would have been surrounded by violent influences, influencing any adjective someone would give him today without knowing his background. He was 10 years old when Robert Kennedy found Mamma Jean hiding with her children, and 13 during the shootout with the Bergerson Construction Company. Of course, he was a frustrated teenager.

Though he was not home often, Big Daddy spoiled Ed Junior by taking him hunting and fishing all over the country, or by buying him new cars when he turned 16, paid for in cash. My dad would wreck the cars, usually because he was high or drunk, and Big Daddy would buy him another one.

My dad has always been rebellious, and has always resented authority, like his father, and tried to get his way with threats and intimidation, also like his father. They clashed often, alternating between gifts of cars and hunting trips and violent outbursts. My aunts said that Big Daddy was “rough” on my dad, without saying more, just as Wendy would not say more about parts of her childhood.

Big Daddy wasn’t home often because he enjoyed his financial success and feeling of importance, and traveled to negotiate contracts and meet celebrities. I imagine that he viewed himself like Jimmy Hoffa, and probably strove to expand his influence nationally. He was also having affairs, which Mamma Jean suspected but ignored so that she could focus on her children, with one exception: my dad. Aunt Janice told me that their mother was afraid of my dad. His temper was quick, and he was strong, like his father. He was young, impatient, unable to control his temper, and quick to lash out. He was probably intemperate, though at the time a Louisiana judge wouldn’t have said that about Edward Grady Partin’s son.

Most teenagers are rebellious, but my dad’s nature – inherited from Ed Senior – elevated the level of his reactions, and his upbringing aggravated his teenage angst. He was a tall young man with dark black hair and eyes so brown they seem black, like Mama Jean’s. Most women thought he was an attractive man, or were drawn to his strong personality. He’s like a rebellious teenager portrayed in movies, angry and defiant, striking fear into the hearts of protective fathers.

People said I looked like him, which I initially took as a compliment. When I was a teenager, parents of girls I dated who went to high school with my dad would forbid their daughters from seeing me again; if their parents had worked for Big Daddy, they would invite me into their homes like family.

My dad sold marijuana and other illegal drugs as a teenager. At the time, marijuana was not only illegal, it was viewed as evil. Smoking marijuana was something only the most uncouth of people did, like the hippies shown on television.

He was an angry hippie, and would probably have dropped out of high school even if my mom hadn’t gotten pregnant. All across America teenagers were preparing to be drafted or to avoid the draft by going to college, or by living in Canada. Ed Junior would have gone to Canada, or hidden in the woods of Louisiana before allowing himself to be drafted by a government he resented because of his family’s lifestyle.

My dad grew his hair long and became an outspoken critic against anyone or anything that imposed rules. The news and national magazines were also his targets, because they were easily controlled by people with influence. He always looked angry in photos, unlike Ed Senior, who was always smiling.

My Aunt Janice said that Mamma Jean was afraid of my dad. Teenage children can be larger or stronger than their parents, or they can be intimidating if they have untamed emotions and access to weapons. Ed Junior’s anger increased as his friends were drafted and sent to a war in which few people believed. He resented the perception that a government could control people, to force them to choose between fighting an unjust war or going to jail.

At the time, Mohammed Ali expressed his anger a way that resonated with my dad. The olympian and national boxing champion who was always smiling and joking declined his draft notice, snd when a reporter asked him why he wouldn’t fight the Vietnamese Viet Cong army for his country, he uncharacteristically replied tersely: “Ain’t no Viet Cong ever called me dark meat,” though he used another word that people starting the war called black men. Mohammed Ali would have beaten Big Daddy in boxing; Uncle Doug said the time his big brother wore boxing gloves was for that Life magazine photo.

My dad seemed to relate to anyone oppressed, regardless of race or religion, possibly because he saw the need for Big Daddy’s work in Baton Rouge, where most workers were cheap, disposable labor used by management to make more profits. Or, perhaps that’s just how Ed Junior channeled his anger and teenage angst, seeing suffering everyone in order to justify his intensity. I like to think that he was a good person who saw injustices and was angry that other people didn’t see them. He was torn – Big Daddy was ‘rough’ on him, but he was good at protecting people who needed protection.

Labor unions were important, especially in the south, where poverty and racial inequity means there are always people available for manual labor, so they were treated badly by companies and employers. Even Mark Twain wrote about the importance of labor unions. His words would be read in union halls decades later:

Who are the oppressors? The few: the King, the capitalist, and a handful of other overseers and superintendents. Who are the oppressed? The many: the nations of the earth; the valuable personages; the workers; they that make the bread that the soft-handed and idle eat.

He was restating what Malachi had said in the Old Testament:

I will be a swift witness against the sorcerers, against the adulterers, against those who swear falsely, against those who oppress the hired worker in his wages

Even Malachi would have admitted that Bid Daddy violated most of the ten commandments. He lied, killed, committed adultery, bore false witness, and worked on Sundays. But at least he didn’t oppress hired labor, and he wasn’t a sorcerer. If he was, I wasn’t aware of it and never saw evidence of him doing anything other than lying, killing, adultering, and bearing false witness. But the people of Baton Rouge loved him, because he helped poor people in Louisiana have a better life. In that light, he was a good guy. The Teamsters even voted to keep paying him a salary for six years when he went to prison again in 1983, around the time my dad went to prison, too.

My dad saw that the Vietnam War was being fought by poor young men, regardless of their race, and he was becoming furious about the thought of being drafted in a year. Like his father, he fought against authority, not nameless enemies who hadn’t done anything to harm him.

The average age of a soldier in Vietnam war was 19 years old, and they disproportionately came from poor families; if you went to college, you weren’t drafted. There wasn’t a union that helped our child soldiers the way Big Daddy protected workers, and my dad’s anger grew. I think that’s why I’m fascinated that Big Daddy knew Audie Murphy; he was a war hero who had lied about his age to go to war at 17 years old, and who was against fighting more wars.

Audie grew up hunting in the woods of Texas after his father left him. In the army, he hunting skills allowed him to become an expert marksman, and his work ethic and bravery led to him earning every army medal possible from United States army including the Congressional Medal of Honor. He became a household name by starring in more than 40 movies after the war. The footage of him in To Hell and Back was reused in so many other films that the image we conjure up of an American fighting against Nazis in Europe is probably Audie Murphy charging German machine gun bunkers. That’s what he won the Congressional Medal of Honor for, charging a German machine gun bunker so that his friends who were out of ammunition could escape. It seemed like an unlikely match with my grandfather.

No one knows for sure how they had met, but newspapers suggested it was because Audie knew Hoffa from Hoffa’s work with Hollywood, and he was trying to get Big Daddy to change his testimony. Other newspapers said they had become business partners, because Audie was known to be low on money and hoped my grandfather had learned enough about the Teamster business to help him.

Audie was ethical. When he was too old to star in more war movies, he declined offers to be paid for alcohol and cigarette endorsements, because he didn’t want to be a bad influence on kids. He wanted to earn his livelihood righteously, and he needed help.

He admitted that addicted to pain medications and sleeping pills and amphetamines, which is how he was able to go to sleep most of his life because of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, PTSD, though it was called Battle Fatigue back then. He became a spokesperson for mental health awareness, and for the dangers of addiction to sleeping pills. He wanted to live righteously, and to share his life experiences for the betterment of other people.

Maybe that’s how he related to Big Daddy, who had become addicted to the same medications, and may have shared symptoms of mental illness similar to Audie’s PTSD. Whatever the reason, it died with Audie in a plane crash in 1971. Some people suspected Big Daddy’s involvement, but by that time there were so many rumors that it was hard to keep track of another one. Regardless of what was happened with Audie Murphy, Ed Senior was spending more time with his newfound celebrity status than with his family, which would have isolated my dad even more.

At the same time, people in Louisiana loved Big Daddy. Political commentators said he could become governor if he had a college degree. That probably endeared him to the working class even more. He brought jobs to our state, and supported all working class people. The Teamsters would go on strike to support teacher’s union strikes, and Big Daddy was known to pay unemployed workers with cash from his pockets. No one cared where that cash came from. He was a hero to many.

Walter Sherman, the head of Kennedy’s Hoffa task force, showed Big Daddy’s in-your-face personality in an interview with Life magazine.

“I’ve dealt with a lot of informers,” Life quoted Sheridan, “and until this guy, they all wanted two guarantees: nothing traced to them, and never call them as witnesses. Ed asked for neither one.”

Big Daddy wanted to be in the spotlight for standing up to Hoffa as much as he wanted out of the Baton Rouge jail. After Hoffa went to prison, all 2.7 million Teamsters knew that Edward Partin had sent him there. There were attempts on his life, and the federal government assigned federal marshals to protect him. For the next 10-15 years, throughout the 70’s and early 80’s, he had federal protection and immunity from prosecution. His status let him become friends with celebrities and make his own deals with the Marcello mafia family and Fidel Castro.

An eight year old boy doesn’t understand all the words he hears, or see the significance of news events. But I can link those events with my time with Wendy, and try to share her perspective as a young single mother, with the challenges of me being a Partin.

Return to the Table of Contents.