A Part in War – Older Version

This is work in progress – literally – because I’m working on this for a few days. Please check back.

After the war, and back in North Carolina, I waited for the army in uniforms that were too small for me. Headquarters company was trying to process me, because they hadn’t been able to do so six months before, when they were already in Iraq. I was waiting for back-pay from my six months of service, which included an extra $110 per month for Airborne hazardous duty, and another $110 for combat service hazardous duty. After my deductions for the college fund, and seriess EE bonds, I’d have at least $400 per month owed to me, and I’d be able to buy so I could buy civilian clothes that fit.

After 500,000 soldiers had deployed to Desert Storm, there weren’t enough green jungle uniforms to replace our tan desert uniforms, and the uniforms I had been issued six months before looked comical on me now. My red beret and shoes fit, but my sleeves stopped a few inches short of my wrists, and my pants were too short to tuck into my boots. I was stopped and reprimanded by officers with fresh uniforms who had held down the fort while we were at war. I was told that REMF’s, Rear Eschilon Mother Fuckers, were important for the big picture, but frustrating to those of us returning without an efficient system. I wasn’t frustrated, but I wished people would stop commenting about my tiny uniform, like the time Sergeant Major Hogard stopped me and asked why I looked so ridiculous.

“What the fuck you wearin?” he asked. I snapped to attention, head up, eyes locked forward, with my arms straight by my sides; but before I could answer he said, “At ease. Ain’t you got a proper uniform?”

I transitioned to the “at ease” position with my arms crossed behind my back. “No, Seargent Major. I outgrew mine in Iraq, and don’t have a new issue yet.”

He was so senior that I never saw him in the war – he met with leaders several levels above what I would see – but I knew him by his reputation as saying anything he wanted. He was the highest ranking non commissioned officer in the 504th, higher than our Top, and was responsible for the health and welfare of 900 men and several boys with uniforms that didn’t fit right.

He spoke to me for the first time as I walked through Fort Bragg, North Carolina, with my shirt sleeves too high, and my pants untucked from my boots, which was almost as bad as if I had worn my dad’s “Fuck U.S. actions in Panama” shirt. Sgt. Major Hogard had been one of the 82nd soldiers who parachuted into Panama and captured their president the year before; I felt that my life had been a funny series of coincidences, but at that moment I was too terrified of Sergeant Major Hogard to smile about it.

“Oh, yeah. You that kid who plays magic tricks and shit, and speaks sand-nigger.” He used a derogatory term for “Arab soldier” that only he could get away with. His service was legendary. He was a character in books about valor, the one who kept a team together when they were all scared boys. Every person who met him said he seemed “real” and “down to earth,” which I learned were euphemisms for “he curses a lot.”

People said he was tougher than woodpecker lips in a petrified forest, and that he was funny. He had survived a year in a solitary prison camp, locked in a small box without light. The VietCong removed him every few days for fresh air and to torture for information about his teammates. When he was rescued, he smiled and joked and called everyone “HUAH,” a sound made by infantrymen for anything from a positive affirmation to general call of enthusiasm.

In prison, the only people who had spoken to him were his captors, and most of them called him nigger and taunted him for suffering for people who didn’t care about him. I didn’t speak sand-nigger, but somehow I managed to learn a few Arabic words and communicate with our prisoners kindly, and the Sgt Major had somehow heard about it. But I didn’t know that yet.

“Well, shit HUAH! Ain’t you got money to buy a uniform in town? You already spend it down in the War Zone?” He was talking about the nearby civilian town of Fayetteville, and specifically about one downtown street that had nothing but bars, prostitutes, tattoo parlors, used car lots, and drug gangs. Soldiers called it the War Zone. I spent a lot of money down there, because a couple of retired veterans had opened a coffee shop with a used book store inside. All of their books had been banned in America, at some point in time, despite the 1st amendment that they peacefully and proudly protected in the War Zone. I’ve always enjoyed reading, even in a war zone. It was cheap rental for their shop, and it let them chat with soldiers who stumbled inside on their way to get a tattoo or prostitute or used car with no money down. They had Mark Twain’s “Huckleberry Fin” and Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird,” both of which had been banned because they used the word “nigger.” You could read about banned books in the war zone, down the street from a civilian owned army surplus store that had new uniforms magically acquired while REMF’s in headauarters company, HQ, completed paperwork explaining why they were out of uniforms.

“No, Seargent Major. HQ hasn’t activated my pay yet.”

“I’ll make it happen,” he said as he moved an unlit cigar butt around with his lips and looked up and down at me, not even pretending to do anything other than size me up. He stuck a hand in his front pocket and fumbled around for a few seconds. “Hey there, HUAH! You want a cigar? I got one here!” His eyes lit up as his hand grasped something in his pocket. “Oh shit! That ain’t a cigar, HUAH! It’s my dick! My big fat black dick! Hahaha!”

I liked him, but I didn’t get a cigar. Instead, he patted me on the arm when he stopped laughing about his big fat black dick, as if to let me know he knew he was playing a role. I tried not to imagine that was the hand he used to grab his dick a moment before. He said he’d get HQ to issue me uniforms and emergency money, and he told me to find him after I got my uniforms squared away. He had been a prisoner of war, and he appreciated people who treated people decently. I grew to respect him even more over the next two years.

I was surprised that he knew about me, a new kid out of hundreds of soldiers under his command. I still had pimples, and I didn’t smoke cigars or engage in weekend team building debauchery in the War Zone. (The joke was that the 82nd was a weekend drinking force with a weekday habit of invading countries.) My platoon sergeant in Iraq, Sgt. Weber, may have mentioned something to our company’s First Sergeant, who we called Robo Top because of his immense size and his robot-like precision as he walked and turned corners.

He was a big person. Even seated, he was at eye level with you as you stood in his office, and would look you in the eyes, with a huge cigar burning in his mouth, as he did one-arm curls with a 45 pound dumbbell, the weight of our ruck sack in leadership courses. His free hand would hold his cigar while he talked, and his breath never raised or lowered to the rhythm of his one armed curls. He epitomized what it means to be temperate, to sail calmly in all storms. I listened to what a man like Robo Top had to say. He never cursed, and he never drank alcohol.

“Dagnabit,” was the harshest thing anyone had ever heard him say. He called his soldiers’ 18 year old wives “ma’am,” and he went to church on Sundays, though he never talked about his personal beliefs when he was in uniform. He loved to talk about the army though. He believed in selfless service to others.

No one messed with Robo Top. As I listened, I’d count the number of curls he did and extrapolate to how many he must do each day. Everyone was motivated to do their best around him. He was the type of leader who would stand between an Iraqi tank and one of his soldiers to protect them.

For some reason, he helped me, and he recommended me for leadership school, forgave me when I din’t graduate the first time, and recommended me again for the second attempt.

He used to meet with the Sgt. Major for weekly After Action Reviews, and he trusted Sgt. Weber, so he may have relayed names higher up. They would have all had to sign off on awards I was given.

I had earned Sgt. Webers trust after a month or two of mistakes, and grew to become allowed to enter bunkers with the first mentor I had in the army, a 26 year old who was supposed to have left the military but had been extended while in Iraq. Sgt. Weber assigned me to Starkey because I was, as he said, “young, dumb, and full of cum,” and he didn’t want me getting one of his soldiers killed because of my ignorance.

Starkey was a 26 year fire fighter who joined the army later in life, and was one of the most respected soldiers in our company. He laughed in all situations, and was generous with his time and wisdom. Between funny stories, he’d talk about men I had met but did not know yet, who had killed Panamanian soldiers in 1989, and one of the men who killed an innocent civilian accidentally, because he had been nervous and shot out of fear rather than purpose. None of those men had slept well since then. Now we were here. Be calm. Look at the stars. Have fun. Take apart the MK-19 and learn how it works. Be able to do that in your sleep. Remain alert, but relaxed. The edge of a bayonet blunts quickly if sharpened too much.

Midway into the war, the two of us captured 14 men in close quarter combat, in a dark underground bunker designed to only allow one person to enter at a time. That wasn’t uncommon, but we treated the prisoners as neighbors, which was less common. We watched them all night because we were in remote locations, and we were transporting them across the desert without things like jail cells. The 14 Iraqi Republican Guard soldiers sat in a circle with their wrists tied at night, and we watched them with M16 machine guns. Senior people had the first or last shift, therefore they could sleep for 6 hours uninterrupted. The next level of privilege had 5 hours uninterrupted sleep, and a few people had to stand guard at 1am or 2am, so they would get two blocks of short sleep in the coldest hours of the desert night. These guard shifts were reserved for the lowest ranking soldiers, or for whoever had pissed off our Sgt. Weber. It so happens I was both.

When I first arrived, before I learned how to be trusted, I was both the lowest ranking soldier and one who seemed to frustrate Sgt. Webber. I deserved anything I received, because I was an ignorant kid who didn’t grasp the reality of our situation yet. But I learned, and after I earned trust by not doing anything else wrong, he became a mentor. But I still had the worse guard shifts. I would eventually do the same to young soldiers. It’s part of the process. What made Sgt. Weber such an excellent leader is that he knew to put the most senior and respected soldier on the worse guard shift with me, and because of me. It was like making him a better leader by pairing him with the worst possible situation: me.

Starkey made the best of it when a lesser man would have complained. I think I met Sgt. Magor Hogard because of him, because word had gotten to the Sgt. Major that I shared a blanket with prisoners. We didn’t have fart sacks – what we called sleeping bags – and were cold, so had taken blankets from some of the bunkers we captured. The prisoners were shivering, so I shared mine. I offered some chicken and rice, though that may have been considered cruel and inhuman punishment. I did a few coin tricks from my spot 20 feet away from them, but that could also be considered cruel, because I never was that good. But they smiled, and everyone relaxed. It made crappy night time guard shifts tolerable, and I learned that most of the prisoners had families at home, and they had been more scared than I had.

This was their job, and under Sadam Hussein you did your job or you and your family could die. These men had stood on the other side of a 6 inch dirt wall in pitch blackness, listening to our breathing as we controlled our breath to listen to theirs, and both sides made choices that led us to guarding them at 2am under a desert sky full of stars that had been shining for billions of years, and would be shining for billions of years after our petty wars ended. I hope they appreciated the night sky as much as I did those nights.

Someone must have told Sgt. Weber what I was doing. He never mentioned it to me, but may have mentioned it his superiors. From that point on, a series of opportunities were presented to me that seem inexplicable otherwise. That’s how I ended up having prickly heat scraped off my back as the youngest person in the course, and how I ended up discussing Hillary Clinton with eleven unnamed soldiers.

I had a privleged time in the 82nd, earning awards and titles beyond my years because of mentors and senior officers who made opportunities happen. It was up to me to do well, but the opportunities had to be given by others. I did well, and I didn’t talk about it, and the opportunities grew exponentially. I won a few awards, but the honors were unique learning experiences. I was even asked to attend dinners with visiting politicians and ambassadors, including the ambassador from Panama, who chatted with the 82nd’s commanding general at our table. He had led the 1989 invasion of Panama; I resisted the urge to mention my dad’s shirt, and that he had been invited to Washington DC to speak on the congressional floor about the right to burn American flags in protest of what he called “some fucked up shit those assholes did.” Though, if I told the whole story, that my dad and most of the country had watched my mentors parachuting into Panama, and they kept me safe, and led to me to having dinner with the invading general and Panamanian ambassador, I’m pretty sure they would have all laughed with me.

People assumed the army had changed me, but I don’t believe we ever really change, we just emphasize some traits and relinquish others, and hopefully we do more of what works and less of what doesn’t work. If you’re an asshole going in, you’re an asshole coming out. If you’ve made mistakes and are open to improving, and are lucky, people in our lives help us through that process. I happened to have many mentors in the army, but the change had already happened.

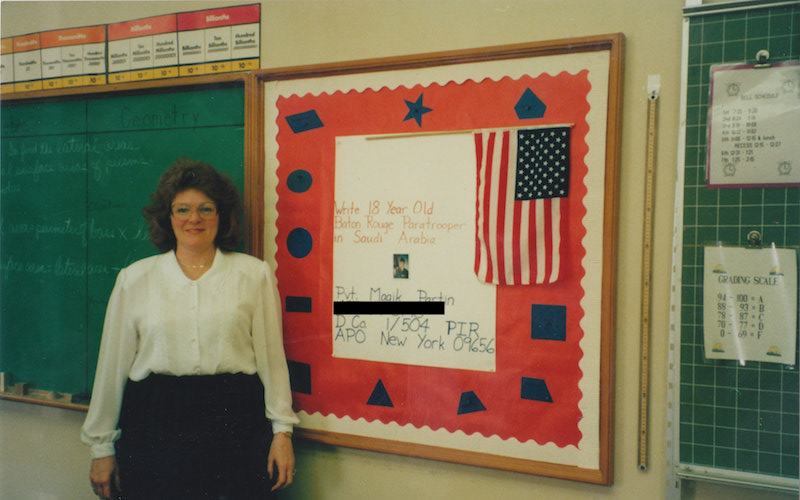

That being said, I changed a lot before I left the army. I became a peace keeper, back in the Middle East, and grew more as an adult. But after I left the army, whenever I was asked how I went from doing drugs and stealing things at 15 years old to where I was now, I’d say, “Coach, and Mrs. Abrams,” but I never came up with a good pun using her name and the M1 Abrams tanks we raced against in Desert Storm.

Return to the Table of Contents.