A Part in War

We landed, and learned that most of the 82nd Airborne Division gone. They had flown to Saudi Arabia to stop Iraqi tanks from continuing their takeover of the Middle East. Kuwait had fallen quickly, and America’s Quick Reaction force had left Fort Bragg North Colina to draw a line in the sand that unambiguously said: no one shall pass.

The world’s oil supply was at risk, and I’m sure someone was concerned about the Kuwait people, too.

Almost all of 12,000 paratroopers of the 82nd were already in Saudi Arabia. A thousand had gone within a few hours, because they were on call as America’s Quick Reaction force. Two thousand more followed a few hours later, and within a few months there were 12,000 paratroopers and almost 500,000 allied soldiers from dozens of countries were under the command of American General Norman Swartzcoff, and we were preparing to invade Iraq and stop their invasion with enough force to reduce them as an immediate threat to the Middle East, then to quickly remove ourselves and protect our lives.

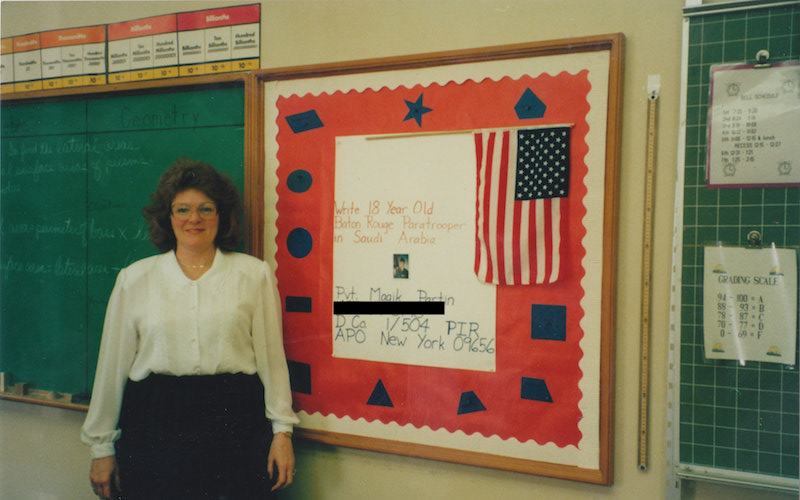

I was one of a few people being prepared to join the 82nd on the front line before the war started. The 82nd would be the first to cross. Their commander had requested extra anti-armor soldiers for the front line. Sergeant Hornung hadn’t been joking or exaggerating: the 82nd commander really had requested more bodies, and that ripple effect had led to me being anti-armor and in an accelerated Airborne school over Christmas. I began listening more closely to older soldiers telling jokes.

The REMFs at Fort Bragg who handled pay and uniforms replaced my green jungle uniform with a tan desert uniform that was one size too big because they only had extra-large uniforms remaining. I did not have time to sew anything on it other than my name, US Army, and the AA Airborne patch for the 82nd Airborne All Americans.

The All American REMFs rushed us through a medical processing assembly line and gave us more shots and vaccinations than I can recall; it must have been more than a dozen. They prepared us for everything known to the U.S. Army at the time, and gave us a gammoglobulin immune system booster for anything they may not know about, or diseases they said we could catch in the War Zone.

Doctors we’d never see again stored the boosters in a refrigerator and did not do the courtesy of warming each thumb-sized glob before forcing it through a large bore needle into our buttocks. A bulge lingered and caused a pain in my butt for ten or twenty minutes as it disolved. I sat beside bald men in uniform who also sat at an angle with their right buttock held off the hard wooden bench as the doctors handed us a jar of pills they said would protect us in case Saddam Hussein used the chemical weapons Iraq stockpiled.

They told us to begin taking one pill a day as soon as we landed in Saudi Arabia, and to inject ourselves with the kits we carried after being exposed to any chemical weapon. They hoped the combination of prevention and emergency treatment would delay death long enough for medical teams to arrive.

I boarded a C-5 aircraft and 17 hours later I was in the coalition force headquarters in Saudi Arabia with people from all over the world being shuttled to their country’s units. They divided us into groups like sorting pieces of mail. Only two of us were going to the 82nd’s front line. They put us on a mail truck, and dropped off mail along our way to the front line.

I rode on top of the truck with an E4 whose name I don’t remember for four days. He had combat experience already. He had parachuted into Panama the year before, and had been in Saudi Arabia for three months before winning an award for something I can’t recall and being given a week of Rest and Relaxation on a civilian cruise ship in the Persian Gulf that gave free R&R to soldiers in Desert Shield.

We traveled for four days as the truck delivered mail and gift boxes from school kids to unnamed soldiers. As we moved closer to the front line, the soldiers were spaced farther apart, and were dug into the ground more deeply. We’d give mail to each unit’s First Sergeant and exchange gossip before moving forward again.

My newfound mentor and I rode on top even as mail emptied because it was fun – only a few months ealier, the most fun thing I could have imagined in high school would have been riding through a desert war with wind blowing through my hair; in my high school imagination, I never thought about how the army would shave my head or realized that I wouldn’t feel the wind through my hair again until after many years passed.

He pointed to things I should learn to notice but had never considered because I had never been in a desert before. He pointed across the wide open sand to a cloud of dust a hundred miles away and asked if I knew if that were natural or caused by vehicles. He pointed to another. And another. I learned to understand wind patterns without needing words to describe cause and effect.

At night, we slept on the ground with the truck drivers and I learned how to use the stars on this side of Earth to always know where I was without needing my compass. I practiced using my compass to triangulate my position from hills dozens of miles away. I was good at it, despite having failed geometry two years in a row in high school. Somehow, triangulation made more sense now, and I could practice hands-on instead of on a piece of paper. And I was choosing to rather than being told to. There were no more multiple choice tests about the theories of life.

Each day, the books and toothpaste and cookies mailed to soldiers from school classrooms across America diminished. My mentor took a few “Adam and Eve” lingerie catalogs that had slipped passed by the Islamic inspectors and gave me one. He said my future team would appreciate them, and not just because the Garden of Eden was supposedly a valley in Iraq that we were near.

This was holy land, and this was a holy war; it was an oxymoron, and 500,000 people of all religions were about to fight 400,000 predominately Muslim Iraqi soldiers.

He gave me cans of chewing tobacco even though neither of us used tobacco. He said tobacco supplies run out quickly, too, and my future team would appreciate the gifts. Tobacco supreses appetite, narrows focus, and passes time. The mail truck dropped him with his team and took me to mine.

Sergeant Webber was waiting with our first sergeant. He was cursing for having a cherry in his platoon so close to the start of the war, and told me to follow him and not touch anything. I touched something interesting on the ground. He yelled and told me to do pushups and I did them as he leaned over me and said we were next to a mine field. He said if I fucked up I’d kill his men. He told me to keep doing pushups until I thought I would stop fucking up. I got up with a new perspective; it was like waking up a different man.

We walked 50 meters to a hole in the ground with a Humvee and TOW II missile system and three men who would be my team. They appreciated the catalog and tobacco. Each Humvee was 50 meters apart. I did not meet anyone other than Sgt. Weber and my three teammates.

I did pushups throughout each day for weeks. When not exercising or learning my team’s equipment, I read Mrs. Abrams bible; it was the only book I hadn’t read yet. The Adam and Eve catalog had long since been circulated to other teams.

When the infantry says “Follow Me” it’s because they are the front line and the farthest away from unnecessary items. Our vehicles were packed with water, ammunition, and Meals, Ready to Eat. We sat on tops of boxes that filled our seats and floorboards. I was given my ration of MREs; we joked and called them Mr. E’s or Mysteries, as in it’s a mystery what’s inside.

My team disliked chicken and rice, so for months they had swapped each chicken and rice for other Mysteries. Sgt. Weber had given them my month’s supply before I arrived, and they replaced all of mine with a month’s worth of chicken and rice. I stopped joking about what today’s Mystery would be after eating chicken and rice three times a day for a few days. I grew to dislike chicken and rice, and hoped our company received more cherries so that I could swap the rest of my MRE’s with theirs and no longer be the platoon’s cherry.

We carried TOW’s but did not mount them on the Humvees because even though they could punch through 38 inches of armored steel and destroy any tank on Earth and kill everyone inside they were slow. A TOW missile traveled 3.1 miles in 17 seconds, and in that time a T-55 tank team could fire seven rounds towards the telltale smoke and sound from our team firing a missile. We’d remain exposed as we guided the missile with hand-steered wires that we tracked through 13X optical sights or thermal images. In the open desert, a T-55 team could kill us before we hit it.

The 82nd had adapted to desert anti-armor needs by installing Browning M2 machine guns and MK-19 grenade launchers and ammunition on our Humvees.

The M2’s had armor piercing .50 caliber rounds; the outer shell was hardened metal and punched through 2 inches of steel and opened a hole for the inner slug to continue moving. They could hit a target 2 miles away, and were fast enough that they would not drop their angle for 1,500 meters; we could intimidate people from 1,500 meters away by aiming a .50 caliber machine gun at waist level that made them chose between death and lying down.

The MK-19’s sent 48 grenades per minute flying 2,000 meters away. The new HEDP highly explosive dual purpose grenades could melt through 2 inches of armor on personnel carriers and explode inside, killing or injuring a dozen people at once. Each grenade would kill anyone within a 5 meter radius and wound anyone within 15 meters.

We took turns dismounting the machine guns and grenade launchers at night, one team staying on guard while the other team mounted the TOW’s. We used their 13X optical sites for daytime guard duty, and 7X thermal sites for nights. Nothing warmer than the cold desert night could sneak upon us.

We slept in shifts. I was a cherry and received the most undesirable guard shifts that disrupted sleep the most: sleep 1-2 hours, wake up and say away for one, go to sleep for three hours, wake up and stay awake for one, sleep another 1-2 hours. I looked forward to more cherries.

I could see a hundred miles ahead with the sites. There was no threat that could reach us within an hour or two, unless by air, and our command center had satellites and radar to help with that. We were looking for vehicles or small teams crossing 100 miles of desert. We had a lot of time to relax.

I’d use the thermal sites to watch mice hiding behind bushes and searching around for seeds in the cold desert nights. When I woke up Starkey woke up for his shift, we’d see if the thermal site could detect a fart. I watched a dark red human shape in front of light red bushes lift a leg, and I saw a thin red cloud form under it, and we laughed and kept life as normal as possible.

It was just like floating in a parachute the first time – I was amazed how quickly I adapted to new situations. Within a few days, the excitement of being in the 82nd wore off, and I began to make jokes, just like in high school classes.

I wrote a letter home, and labeled it from the “82nd AirBored.” Sergeant Weber found it before mail went out, and had me do more pushups as he yelled that my ignorant cherry ass hadn’t been sitting in the desert long enough to be bored, and if I was bored I could dig latrines after my arms failed from doing pushups all day, and that his soldiers missed their wives and children and no one wanted to see my smartass jokes on the outside of my mail. He told Starkey to make sure I stopped fucking up.

Starkey told me about the people in our company I hadn’t met yet, the ones in other vehicles dug out and spaced at 50 meter intervals along the border of Iraq. This was not gossip – he provided facts to help my perspective. They had parachuted into Panama together the year before.

A few were anxious – they had shot and killed civilians in Panama in the heat of battle, and had not slept well since. Real world combat is so different that what people imagine. The best thing we could do was remain polite and calm and unseen. Help keep the energy of a team centered. I began to see more clearly.

I used our Night Obervation Devices to NOD at the stars. It amplified light so much that the sky seemed to be more starts than darkness. I wondered what else had always been happening that I had never seen.

When I was bored of watching kangaroo rats fart and billions of stars forming millions of galaxies, I’d roll half dollars across my fingers as I looked at the horizon, and developed a mindless habit of making one in my right hand disappear as I made the one in my left appear.

A few weeks passed like that, and we were told to prepare to cross the border.

**** write about chaplain ***

Two days later, we watched the coalition air force fly overhead and rain bombs and rockets in front of us for several days. The French then we crossed the border into Iraq and we followed a few hours later.

We drove slowly at first. A Volcano team launched wired explosives 100 meters in front of us in a 20 meter wide path and exploded and shook and removed land mines from our path. Other Volcano teams did the same on our periphery. We moved ahead, aimed our M2’s and Mk-19’s ahead and to the side so that everyone’s periphery overlapped. The Volcanoe teams repacked their rockets and moved to the front and fired the Volcanoe again. We played leap-frog for a day or two until we reached the Iraqi highway that had been used by the Iraqi army to prepare for our ground assault, before the coalition air force rained bombs and rockets on them.

We drove over or around melted highway pavement. We drove over hundreds of dead bodies that squished under our tires. We jolted every time we hit a speed bumps that had been someone’s helmet. We fought briefly when we were outnumbered by a division of T-54 and 55 tanks with more firepower, and were saved by a division of our M1 Abrams thanks. They sped past us and jumped through the air with their computers locking their guns on the outdated manually operated soviet era tanks. They ended that battle quickly.

We walked with machine guns ready and looked for survivors. I saw an interesting bullet as big as my forearm and picked it up. Sergeant Weber yelled at me to set it down and start doing pushups, and he asked me what the fuck I was doing and did I even know what the fuck I just picked up that could have killed us.

“An ADA round, Sergent,” I said, showing off that I had listened to my team.

“Did you mean an 88 round, like an 88 mm or 88 mike round, Partin?!?! Do you know if it’s explosive? Do you how it detonates? Do you know anything, Partin?!?! I don’t fucking think so! So don’t do a fucking thing without approval from now on.” He assigned Starkey to make sure I didn’t fuck up again, or else it would be Starkey he’d take care of.

A month passed, and we learned many things about each other, and how we behaved under stress, and how we learned. I grew up.

We captured an airport by capturing underground bunkers that surrounded it. Each bunker held ten to twenty Iraqi Republican Guards that had invaded Kuwait then retreated to protect this airport after the 82nd arrived and drew a line in the sand. C-130 ghost ships had pummeled the bunkers with 20mm machine guns and 105mm howitzer artillery. We wore reflectors on our helmets to prevent the ghost ship from firing on us, and we waited for them to rain death for a few hours. We captured survivors one bunker at a time.

Their bunkers were hidden from view because they blended into natural rolling sand dunes. We hunted them. Each one had a small openings that led underground to a short maze of turns meant to narrow invaders to one person at a time in darkness. We found one just before the airport and were in a hurry when Sgt. Webber chose my battle buddy and me to go first. We used pistols that were easier to maneuver in tight spaces, and carried our NOD’s but did not use them because they amplify light but do not create it – the bunkers had no light. Starkey gave me a nod, then ducked his head and stepped into the darkness. I followed.

It was as dark as dark can be. I smelled dirt from the walls and the unmistakable stench of humans who had not bathed in days or weeks or months. We smelled like that, but we were used to our smell. I knew from wrestling in high school that different races smelled differently, but I had never smelled a live Arab this closely before. It was unremarkable.

I recognized the smell of a kerosene camping stove that should not be used indoors, like the one my dad used inside of his cabin in Arkansas. I could not identify the other smell but was sure it was a spice used for cooking.

I could hear someone on the other side of a dirt wall breathing. I tried to control my breath and listen more closely. They did, too. We were both aware that we were aware of each other. Five or ten minutes later Starkey and I held our pistols on them as we walked them outside and our team surrounded them with machine guns. They laid down their weapons and surrendered. Neither of us remember the details of what happened; it was unremarkable at the time, like many times when you’re focused on something that’s difficult to describe with words.

We brought lights into the bunker to look for booby traps and anything that could give us useful information. We found a few things, and lingered to look at how they had lived for months.

They had been living off of canned tomatoes and a spice not unlike paprika as the air force bombed their bunker. Stacks of unopened cans lined one wall, and stacks of empty cans lined another. Ammunition lined a third wall. The final wall had personal items.

They kept an American movie poster on their wall from the 1987 science fiction movie “Predator.” The poster was translated into Arabic and showed an angry and muscular Arnold Swartzenegger holding a machine gun and grenade launcher before he was the governor of California. In the movie, his special forces team fights an alien predator hunting humans in a jungle. One of the soldiers was a professional wrestler Jesse “The Body” Venture; he spat tobacco juice and said “I ain’t got time to bleed” before destroying everything in site with a massive machine gun before becoming the real life governor of Minnesotta.

Like most boys, I had liked the movie. As a soldier, I wondered why the Iraqi Republican Guard would keep that poster in their bunker as American special forces teams hunted them. I never learned.

When you’re a cherry and the youngest soldier with veteran soldiers you’re given piles of unwanted Chicken and Rice MRE’s and the most undesirable guard shifts. Starkey and I stood guard on the 14 prisoners between 0100 and 0200 hours every night and watched Muslim men from the Republican Guard shiver in cold and try to be comfortable with their hands wrapped together. I shared a blanket from a pile we had found in other bunkers.

We inspected what we found in their pockets. They were Republican Guard, but had their uniforms from us and wore common soldier versions. We found their uniforms with Kuwait money, and personal items of value from Kuwait people. They had wallets with personal items they were allowed to keep, and had copies of the Koran just like I carried Mrs. Abrams’s New Testament. I remembered my comic book, and wondered what they had left behind, and if they had had people like Mrs. Abrams in their lives. I hoped so.

I found their identification badges and photos of them with their families. They averaged 26 years old. I was a kid holding a machine gun at fathers of children – even then I realized I was a kid holding other kids’ fathers at gunpoint, because I remembered being held at gunpoint by men with my father during War on Drugs. I hated it when I was 12 years old, and I couldn’t imagine it now that I was 18 and could fight back. I thought about my dad in prison, and how I would do anything to never be a prisoner as I kept my machine gun pointed at prisoners I had captured.

I thought about life from 0100 until 0200 hours every night. I thought about what Mrs. Abrams had said about forgiveness, and neighbors. I don’t remember looking up at the stars those few nights. I grew in ways I still don’t understand.

I was too busy during the daytime to think about much. We were preparing to capture an airport with soviet MIG fighter jets and surrounded by anti-aircraft defense guns. A personell carrier from the rear arrived and took our prisoners. I never saw them again.

We captured the airport. We were ordered to move to another target, and to blow up the airport so Iraqis couldn’t use it to fly in troops behind us. Teams of experts with various skills assembled, and we blew up the airport with several types of explosives and a 15,000 pound bomb dropped from a C-130.

The explosives were on the ground, the 15,000 pound bomb was dropped by parachute and detonated above the airport to maximize damage. The combined explosives created a mushroom cloud could be seen for hundreds of miles, like I had imagined I’d see after a nuclear bomb destroyed a city. We took a photo from my disposable camera that only had 12 photos, and moved on.

General Norman Swatzcoff said Desert Storm was over two months later. He became known as Stormin’ Norman because of the quick and decisive victory. We spent a month escorting different coalition ground force units back to a base in Saudi Arabia and returning into Iraq to escort more. The Islamic Iraqis were still fighting Kurdish and Chaldean people in Iraqs but we were ordered to not interfere and to not fire upon anyone unless they were attacking a coalition force.

We camped one night in Iraq and unarmed Kurdish famers and fathers drove their old and worn trucks from their village to meet us. One spoke broken English but we understood that he was asking our platoon sergeant to protect them from the Iraqi soldiers. Sergeant Weber said we couldn’t. The man begged to be given guns, “so that we may protect ourselves.” Sgt. Weber said we couldn’t. They left.

The next morning the Iraqi soldiers moved through their village and we could hear soviet .51 caliber machine guns firing for almost an hour. They were done by lunchtime, and moved to another village suspected of helping Americans during the war that Stromin’ Norman had ended a few days before.

We radioed commanders and were given permission to enter their village and perform medical aide. There were no buildings thick enough to protect families, and we saw what .51 caliber machine guns do to children. Each round took off any arm or leg it hit. Our .50 calibers could fire 1,800 rounds per minute. I thought about how I could have stopped them if I had been willing to disobey orders. Everything’s a choice.

A few months later we were back in Saudi Arabia, cleaning sand and dirt from our equipment and loading it on C-5 and C-141 airplanes to return home. To relax, we played games stretch near Kobar Towers, where we took showers for the fist time in four months and were able to walk around without bullet proof vests and relax.

We relaxed by throwing bayonettes at each others feet. If it stuck into the ground within a blade length that person moved their foot to touch it, then threw at your foot. The goal was to stretch other players legs apart until they lost balance and stumbled. The last man standing won. I won often.

My friend, Todd, was the world champion knife thrower and had trained me. It’s how he passed the time as his father died of aides. I thought of my Abrams brothers from another mother, and how we had joked about throwing knives and shooting machine guns since we had been little kids, which wasn’t that long ago.

We had bragged about what war would be like and what we’d do in combat, and we had admired Arnold Swarzeneger and Jesse The Body Ventura for apparently holding machine guns with one hand and shooting more rounds than an entire team of real people could carry, I now knew. It had been almost a year exactly since I had studied for high school final exams; I never did pass geometry, yet I was now good at it using maps and compasses and radioing coordinates for air strikes.

I’m glad I learned to throw a knife in high school, and I had fun playing stretch with my paratrooper brothers. Some men from my company I had not met in person walked over and joined us. We had not met because our vehicles had stayed 50 meters apart for the past few months, but we knew each other’s voices.

We were part of the 5150 club, and had used a radio frequency setting of 51 and 50 and thumping beats from Van Halen’s recent 5150 album. We used nicknames – never use a name over the radio that an enemy could use – and they called me “Secret Agent,” pronounced See-kret A-Gent, like the sherif from Louisiana pronounced it in a popular James Bond movie. They said I sounded like him on the radio.

We formed mental images of each other in our minds based on voices, and had the first chance to see if we had been wrong. One of my 5150 friends walked away after loosing stretch and I heard him say, “Wow. Partin’s a big mother fucker.”

I had never heard that before, unless someone was talking about my dad or one of the men in his family. I had forgotten that my uniform had been baggy on me six months earlier, and I hadn’t noticed that it fit perfectly now.

A few weeks later I was back in Fort Bragg and tried putting on my green uniforms again, but the sleeves were almost three inches too short. The pants that had been baggy were tight, and the pant legs were no longer long enough to stay tucked into the boots. The jungle boots cramped my toes as I marched in them. I had grown several inches and put on almost 45 pounds of muscle. Seargent Major Hogard stopped me and told me how I looked.

“What the fuck you wearin?” he asked.

I snapped to attention, and before I could answer he said, “At ease. Ain’t you got a proper uniform?”

I transitioned to the at ease position and replied as confidently as I could, “No, Seargent Major. I outgrew mine in Iraq and don’t have a new issue yet.”

“Well, shit HUAH! Ain’t you got money to buy a uniform in town? You already spend it down in the War Zone?” He was talking about the nearby civilian town of Fayetteville, and specifically about a downtown street with bars, prostitutes, tattoo parlors, used car lots, and drug gangs. Soldiers called the War Zone. You could catch all kinds of diseases there; we were given a gammoglobulin shot every six months, whether we wanted one or not.

“No, Seargent Major. HQ hasn’t activated my pay yet.”

“Oh, yeah. You that kid who does magic tricks and shit, and speaks sand-nigger.” I remained at ease. He chewed on a unlit cigar butt and rolled it to the other side of his mouth as he looked at me up and down.

“I’ll make it happen,” he said.

He stuck a hand in his front pocket and fumbled around for a few seconds. His eyes lit up as he found what he had been searching for. “Hey there, HUAH! You want a cigar? I got one here!”

His smile widend and his white teeth flashed as he said, “Oh shit! That ain’t a cigar, HUAH! It’s my dick! My big fat black dick! Hahaha! HUAH!”

I didn’t get a cigar. Instead, he patted me on the arm when he stopped laughing, as if to let me know he knew he was playing a role. Sgt. Hornug had done the same thing months before. This time, I tried not to imagine that was the hand he used to grab his dick a moment before.

He said he’d get HQ to issue me uniforms and emergency money, and he told me to find him after I got my uniforms squared away.

The Sgt. Magor had been a prisoner in the Vietnam war. His captors kept in a small metal box without light or food for weeks at a time. They would take him out and beat him and call him nigger and tell him that his white commanders didn’t care about him and that he should tell them everything he knew about American plans and methods. His team said he always had a smile and joke and a cigar ready, even when rescued from that box after having been tortured.

I didn’t know all of that when I met him, and only learned it from a few people who knew and shared one of the Vietnam books that mentioned a character named Hobo. Like all characters briefly mentioned in a story, Hobo probably had a lifetimes of stories before and after the wars he had experienced; in the days before he became Hobo in the Vietnam War, American whites made him sit in the back of a bus. I saw my own wartime transformation in a new perspective; I had begun lucky, and had my future ahead of me as a white male with a free library card.

I began receiving a series of opportunities. We were still America’s Quick Reaction Force, and for 365 days a year, at least one batallion of 1,000 82nd Airborne paratropers remained on two-hour alert to go anywhere in the world. I was allowed to go to other schools, like Air Assault, spending three weeks rapeling out of helicopters into small clearings in the woods, and setting up emergency helicopter landing zones. I won “soldier of _____” awards, and was invited to formal dinners with division commanders and senators and congressmen. We wore formal uniforms, and were given tutorials on how to use fancy dinner plates, and told to curse less often.

In one dinner, the Panamanian ambassador to the U.S. joined our table. The 82nd commander was there. A few average enlisted soldiers were asked to join, to show what a typical 82nd soldier was like to a man who had seen us parachute into his home country. Most of the “soldier of _____” from other battalions were older, more seasoned, and told of how their father and grandfather had served.

When it was my turn to talk, I said I was the first in my family to graduate high school, and that my dad and his dad had gone to prison. I omitted that my father had sued his university to allow him to keep wearing a shirt that said, “Fuck U.S. Actions in Panama,” and that he had mailed me anti-war news articles during the war, and wrote how he was disappointed in me. I also didn’t say that my grandfather may have killed America’s most decorated army soldier. Everyone there would have known who Audey Murphey was; he was still famous in the army.

I said I had been in the foster system and made an adult at age 16, and had joined the 82nd to serve my country, challenge myself, and to earn the army’s college fund. The table paused for a few seconds. They asked what made a difference, how I broke the cycle. I said my high school wrestling coach and one of my foster moms – it would have taken too long to list everyone.

Our battallion went on two week leave after that dinner. I flew to Arkansas to see my dad first. He picked me up at the Little Rock airport. I crawled into his truck and wanted to tell him all that had happened, but he began telling me about what he had done and how worried he had been. We drove an hour to see our old land that he had sold to pay for college. I asked him to not smoke joints around me because the 82nd tested us randomly, and I did not want his second hand smoke. He pointed at me with his right hand as he steered with his left and looked at me and told me I had gotten arrogant, and that I wasn’t too big to get an “ass whuppin”. He kept talking, and when we parked and stood up outside I noticed the difference in my height – I was looking straight at him instead of up at him for the first time.

He noticed too, and said I must think I was a hot shot now, a big fuckin’ soldier boy who killed villages and burned babies – he was speaking quickly and not making sense. He poked his finger into my chest hard enough to knock me backwads. I said nothing, and looked towards my feet. He told me to look at him and poked my chest again. And again. I felt my anger building and saw that I could react at any moment.

I chose to act. When his finger moved towards my chest again I deflected his forward momentum and stepped through his legs, bringing my hips under his center of gravity. My arms went past him then upward, and I looked towards the sky as I stood up and lifted him to my shoulder height. I pivoted, and brought his body down flat onto the ground, face first and hard enough to knock all wind out of him. I followed, and locked his waist down with my legs, and held his torso down effortlessly by placing a few fingers between his shoulder blades. He yelled and cursed and tried to reach behind his head and grab my arm and told me he’d ‘whup my ass’ when he got up.

I felt sadness, anger, and confusion but knew I wouldn’t react. I wasn’t sure if I could pull a punch but chose to try. Without thinking, my first and second knuckles aligned with my wrist bones and forearm bones into a straight line that would not dissipate force and could crush through a temple and send bone fragments into his brain and kill him. I aimed lower, and pulled the punch so that it blackened his right eye. He became quiet. I immediately followed with two more punches and jumped off of him as I saw my body increase intensity of the punches. I had wanted to stun him, and to leave a black eye so that he would remember tomorrow and we would not have to have the same conversation again. Our relationship was not the same after that day.

I went back to the Little Rock airport, and flew to see my girlfriend in Baton Rouge. We visited Mike and Wendy. She had not written me in the war because she could not find the words to convey her sadness and regret. She hugged me and showed me the news articles she had cut out and tried to follow where the 82nd was moving during the war. In that room, I saw a photo of me in Wendy’s home for the first time. It was me at five years old and on Prince Edward Island, from when Uncle Bob had taken us. Cristi and I stayed at their house, and I used the time I would have spent in Arkansas to get to know Wendy more.

We didn’t say “I love you” when I left, from habit, but I saw her in a new light now that I was bigger. I saw my dad pushing her when I was six or seven, telling her to let me visit him in Arkansas no matter what the courts said. I saw her crying – I hadn’t thought about that part in the memory before.

I couldn’t imagine not being able to stop someone from pushing me or anyone else again, and I felt neither anger nor sadness. I felt an unshakable realization arise from deep within me, and I had no doubt that I’d never let anyone push anyone else around, no matter what the consequence to me. I was bigger, and had realized that everything’s a choice.

I returned to Fort Bragg and served on America’s Quick Reaction Force. I’ve done everything I could since then to protect people peacefully.

Return to the Table of Contents.