Wrestling Hillary Clinton: Part II

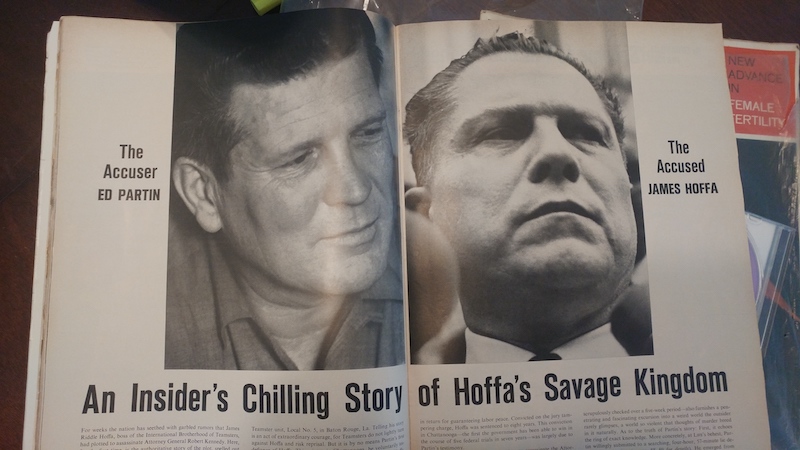

“Here, Edward Partin, a jailbird languishing in a Louisiana jail under indictments for such state and federal crimes as embezzlement, kidnapping, and manslaughter (and soon to be charged with perjury and assault), contacted federal authorities and told them he was willing to become, and would be useful as, an informer against Hoffa, who was then about to be tried in the Test Fleet case.

“A motive for his doing this is immediately apparent — namely, his strong desire to work his way out of jail and out of his various legal entanglements with the State and Federal Governments. And it is interesting to note that, if this was his motive, he has been uniquely successful in satisfying it. In the four years since he first volunteered to be an informer against Hoffa he has not been prosecuted on any of the serious federal charges for which he was at that time jailed, and the state charges have apparently vanished into thin air.“

Chief Justice Earl Warren in Hoffa versus The United States, 1966; Warren was the only one of nine justices to vote against using Edward Partin’s sworn testimony to convict Jimmy Hoffa.

I was 16 years old at the beginning of my senior year in high school. But, by a quirk in Louisiana law I was a legal adult, just like Hillary, because was emancipated the summer between my junior and senior year of high school. I couldn’t vote buy beer like he could, but I could get a driver’s license and sign contracts without parental consent; tat’s how I was in the army’s delayed entry program.

I grew up in and out of the Louisiana foster system. My dad, Edward Grady Partin Junior, was the main drug dealer of Glen Oaks High School and most of rural Baton Rouge; because of his father and his name, he was immune from prosecution as long as Jimmy Hoffa was in prison. As Chief Justice Earl Warren said, without Big Daddy’s testimony, there would not be a case against Hoffa; so to keep Hoffa in prison Bobby Kennedy and FBI director J. Edgar Hoover set up federal oversight to ensure no one named Edward Grady Partin was convicted of state level crimes; those systems, or the culture around those systems, were so deep that they persisted after Bobby was assassinated in 1971 and Hoover died in 1972.

During most of the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, Big Daddy was elk hunting in a Flagstaff cabin Bobby and Hoover had arranged for him as a way to slow him down. In 1971 and from his New Jersey prison cell, Jimmy Hoffa promised Nixon millions of dollars in campaign funding and his endorsement and the provable votes of almost 3 million Teamsters if Nixon could get Big Daddy to recant, which meant offering him a presidential pardon for perjury as the only witness against Hoffa 1964. Big Daddy put aside his elk hunting knife and was flown to San Diego to meet with Nixon in his San Clemente home and negotiate a preemptive presidential pardon if he recanted his testimony against Hoffa. Big Daddy finally declined to recant, and President Nixon pardoned Hoffa the summer 1971, only a few months before I was conceived. Though free, Hoffa’s pardon prevented him from working with the Teamsters for eight years, and, as a favor to Nixon’s campaign, that he travel to Vietnam and negotiate the release of American prisoners while Nixon tried to scale down the conflict. Hoffa wanted nothing more than to return to power, so he still needed my grandfather to either recant his testimony or to claim that the FBI illegally used wire taps against Hoffa, which would remove the original charges from 1964. Pressure was still being applied to Big Daddy, and from my family’s perspective nothing changed when Hoffa was released.

In the early 1970’s my dad lived with Grandma Foster, Big Daddy’s dad, who lived five blocks from Granny, my mom’s mom. My dad deflowered my mother, a junior at Glen Oaks named Wendy Anne Rothdram, just after the 1972 New Year. They eloped to Woodville, Mississippi where my dad still had family and state laws didn’t require parental consent for a 17 year old boy to marry a pregnant 16 year old girl. They returned to Baton Rouge as Mr. and Mrs. Edward Partin and moved into one of Big Daddy’s houses; conveniently, no one needed to change the name in the phone book, because it was already listed as Edward G. Partin. The home was in a new suburb by the thick forests and murky water of the Achafalaya Basin, where my dad farmed a few mamajuana fields and my mom grew heavy with me in her belly.

Soon after I was born, my dad and a group of his friends rode off on their motorcycles all the way to Miami, then took boats hopping around Carribbean Islands before making it to Kingston, Jamaica, to attend a Bob Marley concert and to buy bootleg prescription opioids in bulk. They took their time getting back to Baton Rouge, where my dad would eventually be caught with enough opioids to sedate all of southern Louisiana. While he was gone, my mom had a series of nervous breakdowns and fled the state with a young man she met at a coffee shop who was looking to share gas costs on a trip to California. I was left at a day care center, where my mom left the phone number of her best friend from Glen Oaks, Linda White, as my emergency contact.

Judge Pugh of the East Baton Rouge Parish family court removed me from my parents’s custody and placed me with Linda’s parents, my MawMaw and PawPaw. Judge Pugh died of alleged suicide soon after, and his successor was Judge JJ Lottinger, a 30 year veteran of state legislative law who had worked with three Louisiana governors trying to rid the state of Big Daddy, the same way Bobby Kennedy worked with President Kennedy to remove Hoffa. Judge JJ, who referred to Judge Pugh as “the trial judge,” summarized my case and it became a permanent part of court records in the East Baton Rouge Parish 19th Judicial District.

Like most of my family history, this part in my story is publicly available on the internet, if you know which Edward Partin and which Jason Partin you’re looking at and can trace the history for more than forty years. In September of 1976, Judge JJ summarized my history when he wrote:

This is a suit by Edward Partin, Jr., plaintiff, seeking a divorce from his wife, Wendy Rothdram Partin, defendant, after having lived separate and apart for more than one year following a judgment of separation from bed and board. Plaintiff also seeks custody of the minor child, Jason Ian Partin, and the defendant reconvened asking that she be granted the permanent care, custody and control of the minor child.

The Trial Court had previously, by ex parte order, awarded the temporary care, custody and control of the minor to Mr. and Mrs. James Ed White. Following trial on the merits, plaintiff was awarded a divorce as well as the permanent care, custody and control of the minor child, with the temporary physical custody of the minor child to remain with Mr. and Mrs. James Ed White. The defendant has appealed this judgment as it regards the custody of the child.

This couple was married when plaintiff was 17 and the defendant was 16 years of age. Nine months following the marriage, they gave birth to young Jason. While we are not concerned with the facts surrounding the separation and divorce, it was apparently one of incompatibility as defendant testified that at the age of 17 she found herself married to a man who did not love her and so she left. Her testimony was as follows:

“As I say I was emotionally upset. I was receiving little support from Edward. I was scared, very confused. I didn’t know exactly which way to turn. I felt I had no one to listen and help with the situation at hand.”

Several weeks later she returned and lived with her husband again. She found that the situation hadn’t changed, and felt she had to get away again. She heard of a man who wanted someone to share expenses on a trip to California, so she quit her job and with her last wages left with him. She testified that she had no sexual relations with this man, and plaintiff does not accuse her of such. Following this trip she returned to Baton Rouge still emotionally upset. Her husband was suing her for separation and told her he was going to take custody of Jason. She went to live with her aunt and uncle, got a full time job with Kelly Girls paying $512.00 per month.

In February, 1975, the defendant’s mother was injured in an accident and she moved in with her to care for her. In September, 1975, following the recuperation of the mother she returned to live with her aunt and uncle.

During these above periods of time, the minor child lived with Mr. and Mrs. White. The Whites came to regard Jason as their own and, although the separation judgment awarded custody to the plaintiff with reasonable visitation privileges to the defendant, the Whites decided the defendant-mother could only see the child two days a month and that she could never keep the child over night. The reason the defendant did not contest custody at the separation trial was because at the time she felt unable emotionally and financially to care for her son.

We note that the petition for separation was grounded on habitual intemperance, as well as abandonment of the husband and the minor child. There are no other grounds listed for the separation nor for custody. The petition for the separation and custody of the minor child was not contested by the defendant, and a default judgment was granted. Defendant testified in the instant proceedings that the reason she did not contest custody in the separation proceeding was that she was not financially or emotionally capable of caring for the minor, and that knowing the Whites were going to be caring for him, she knew he would be in good hands.

Though the petition for separation had as one of its allegations “habitual intemperance”, the plaintiff in the instant proceeding testified that he had never accused his wife of drinking, nor had he ever seen her drink.

The welfare of the child is the main issue that the Court is concerned with. This issue is more important than any wishes or wants the parents may have. Fulco v. Fulco, 259 La. 1122, 254 So.2d 603 (1971), rehearing denied (1971). As a general rule, and in particular where children of young age are involved, preference is given to the mother in custody cases. This preference is very simply explained, the mother is normally better able to care for the child and look after the education, rearing, and training necessary. Estes v. Estes, 261 La. 20, 258 So.2d 857 (1972), rehearing denied (1972).

No argument is made that the mother is not now morally or emotionally fit to care for the child, or that the house in which she lives is not a proper place to rear a child. In fact, the Trial Judge admitted that it was a fine home.

The Trial Judge has not favored us with written reasons for judgment, however, we must conclude from various statements by the Trial Judge that appear in the record that he could find no fault with the defendant, nor was there anything wrong with the house in which she lived. It thus becomes apparent to this Court that the Trial Judge applied the “double burden” rule to the defendant. We have already ruled that the “double burden” rule does not apply in this situation, and thus, under the established jurisprudential rules, we can see no reason why the defendant-mother should not be granted the permanent care, custody and control of the minor child with reasonable visitation privileges granted to the father.

In consideration of our above opinion, there is no need to discuss the specification of error as to the ex parte granting of custody to the Whites.

Therefore, for the above and foregoing reasons, the judgment of the Trial Court is reversed, and IT IS ORDERED, ADJUDGED AND DECREED that the defendant-appellant, Wendy Rothdram Partin, be and she is hereby granted the permanent care, custody and control of the minor, Jason Ian Partin, and IT IS FURTHER ORDERED, ADJUDGED AND DECREED that this matter be and it is hereby remanded to the Trial Court for the purpose of fixing specific visitation privileges on behalf of plaintiff-appellee Edward Partin, Jr. All costs of the appeal are to be paid by plaintiff-appellee.

At the same time Judge JJ began removing me from any Partin custody, my grandfather began being prosecuted with the full extent of Louisiana power, and in 1979 he would be sentenced to eight years in prison. During that time, even Big Daddy was unable to help my dad gain custody. Judge JJ, finally free from federal oversight that had protected the Partins, spent about a year ignoring my dad and helping my mom become stable before returning my custody to her.

That report isn’t completely accurate. The “fine home” mentioned by Judge JJ, a reference to Judge Pugh’s statement from soon after my mom returned from California, was a gross exaggeration; it was a cockroach infested shithole behind the dumpsters and deep frier exhaust of an all-you-can-eat Chinese buffet on Florida Bulevard, just across from Belaire High School, which I’ll talk about later in this story. My mom had steady employment and the shithole she was renting had the state’s prerequisite second bedroom for me, so Judge JJ returned my custody to her in September of 1976, a year after Hoffa vanished. By then, there was no more need for any Edward Partin to receive any form of special treatment from Louisiana courts.

The Whites appealed Judge JJ’s decision, and I floundered back and forth for another few years until Big Daddy went to prison in 1980. After that, and because my dad no longer had Big Daddy’s homes to live in, my dad and mom decided to split custody of me between Louisiana during the school year and Arkansas over summers, Thanksgiving, Christmas, and Easter breaks. That aggreement stopped when my dad went to an Arkansas federal prison in 1986, the same year Big Daddy returned to Baton Rouge. I spent most time with my mom, but practically out of habit I spent most of the summers and holidays with family, like Auntie Lo and Uncle Bob, Granny, and Grandma Foster, all of whom had opened their doors to either my mom or dad when they were teenagers and were willing, if not eager, to have me stay, too.

In the spring and summer of 1989 I lived with Auntie Lo and Uncle Bob, my mom’s aunt and uncle from Canada, but Uncle Bob developed an aggressive spinal cancer and was in Our Lady of the Lake Mary Bird Cancer Center for about two months. He returned home to begin hospice, and he died on 15 August 1989.

His obituary was printed in the Baton Rouge Advocate. It said:

Desico, Robert M.

Died 4:50 p.m. Thursday, August 15, 1989, at his residence in Baton Rouge. He was a naitive of Canada. Memorial servicses at St. George Catholic churce at 10 a.m. Friday. Survived by wife, Lois H. Desicco, a sister and brother-in-law, Rose D. and Clarence Petipren, Florida’ a niece, Wendy Patin, Baton rouge, and a great-nephew, Jason Partin, Baton Rouge. Preceded in death by parents Phillip and Blance Provinceal Desico. In lieu of flowers, memorial donations may be made to a charity.

As Uncle Bob lay dying, I petitioned the new family court judge, the coincidentally named Judge Robert “Bob” Downing, for emancipation from my family. My court case was scheduled, and it turned out that Uncle Bob died only a week before I met with Jude Bob to decide my future.

Like most people in town, Judge Bob knew the Partins well. He had taken over from Judge JJ and knew the drawn-out drama of my case, and of course by then everyone in America had seen Brian Dennehy portray Big Daddy in 1983’s Blood Feud. People in Baton Rouge were also reminded of the Partins every day, because Big Daddy’s little brother, Douglas Westley Partin, was president of the Teamsters, and my dad’s little brother, Byron Keith Partin, was a senior business agent; they had Big Daddy’s bulk and charming smile, but only a smidgen of his charisma, therefore the news reported more of the trials of Louisiana labor than celebrations of labor leaders. My dad’s imprisonment had made local news, too, because his name was Edward Grady Partin and Big Daddy was still revered in town, maybe more so because of his declining health.

My dad was out of jail by the time I petitioned for emancipation, but I hadn’t seen him in around a year or two. Judge Bob called a meeting with my mom, who was in another bout of depression after Uncle Bob died.

My mom stared down at her hands and wrung them together as she listened to Judge Bob, and she didn’t deny that when Uncle Bob was dying she told me I could move back in with her, but, like how she had become an adult at 16, I would have to leave and take care of myself the day I either dropped out of school or graduated.

I’d be 17 then, I told Judge Bob.

I’d be six months away from being able to get a driver’s license, I explained.

I said I didn’t earn enough with neighborhood magic shows to pay my own way, and without a car I couldn’t do shows in nicer neighborhoods. wanted to go to the downtown wrestling camp more often, I added. And I wanted to join the army and get the college fund, I told him. To do all of that, I needed to be able to sign paperwork as an adult.

Judge Bob said that if I wasn’t to follow in my dad’s footsteps, I needed to be emancipated. My mom sat there, staring down at her hands wringing in her lap, and mumbled under her breath that I was just like my dad.

Judge Bob either didn’t believe her or felt that how close I was to being like my dad was irrelevant to the question at hand. He said he would grant my emancipation request. His desk thudded when he stamped my petition with the raised seal of Louisiana, a mother pelican nesting baby pelicans, and he sprawled his name across the seal and scribbled the date, 28 August 1989.

He handed me the paperwork and reminded me that if I were to follow in my father’s footsteps, I would be tried as an adult in the criminal court, and not even he could help me then. I said I understood.

I walked out of Judge Bob’s office with Judge Bob’s signature on my emancipation paperwork. My mom and I parted, and that was the last I’d see of her for a few months. I took the paper to the court’s main office to file a certified copy on record and to ask for an envelope or folder to hold my original. The piece of paper and all the privileges it would provide only had one sentence typed in black font, but it was longer than a legal sized paper and looked comical, an oversized piece of paper with a few letters across the top like a sprinkling of pimples on a big kid’s forehead.

A court secretary gave me a legal sized envelope, and I carried both to meet my girlfriend, Lea, who was waiting for me in her dad’s ramshackle but reliable work van. I plopped into the passenger seat and held up my emancipation paperwork and the envelope and grinned, flashing the braces across my teeth.

“It’s a legal piece of paper that doesn’t fit in a legal sized envelop,” I said.

She laughed and I folded the paper to fit into the envelop. She started the van and pushed a cassette into her tape deck and handed me the case.

She lit a cigarette and asked, “Have you heard of this yet?”

I hadn’t.

“Guns and Roses is my new favorite,” she said as she pushed play.

The tape was called Appetite for Destruction. It was a legitimate copy with color artwork, not one of the Zeroxed black and white covers of bootleg cassettes a lot of kids around Belaire had. The cover was an ornate cross like you’d see in an old Catholic church, but with four skulls wearing different hats at each tip of the cross; one skull wore a magician’s top hat,

I knew a lot of similar bands as Lea, bands like Van Halen, Ratt, Motley Crue and others with band members who had enviable mullets, but I had never heard of Guns-N-Roses. Their debut album was a hit the year before, but trends took a while to reach all the way down to Baton Rouge.

Lea rolled down her window to let out smoke and turned up the volume. For the first time, I heard Axl Rose’s wailing voice leading into Welcome to The Jungle, and Slash’s guitar riffs ramping up to meet him.

She put the van in gear and we left the courthouse and rocked out on the way to the recruiter’s office on Government Bulevard. It was so close to the courthouse that Lea didn’t finish her cigarette and Axl was only partially through It’s so Easy when she parked and I walked into the recruiters office.

He was surpised to see me again. He was an E6, slightly overweight and was sitting behind a cheap desk adorned with fliers advertising the latest recruitment campaign. Their slogan was, I felt, cheesy: “Be All You Can Be.” A slogan like that could only be contrived by someone who didn’t wrestle.

I had been at the recruiter’s office a month before, when Uncle Bob was still sick but unquestionably dying, and the recruiter told me I needed my parents’s signature to join the army. He was from another state and didn’t recognize my name, and when I explained my situation he suggested getting emancipated. Considering how sluggishly things creep along in a muggy Baton Rouge summer, my emancipation happened faster than anyone imagined possible. By comparison, when Judge Lottinger regranted my mom custody of me in 1976, I languished in the foster system for another three years. Because of experiences like that, I could see how the recruiter didn’t think I’d be back so soon.

I handed him the bulging envelop.

He unfolded the larger-than-legal paperwork and glanced at the single line that said I was emancipated. He looked up at me from behind his desk.

I pointed out the raised seal and Judge Bob’s signature, just in case he doubted the authenticity.

He said he had seen one before, and we instantly began the process of me joining the army at age 16. I already knew what I wanted, and he typed it into my delayed-entry contract. I was schedule to leave 11 months later. If I graduated high school, he said, I would take a bus to New Orleans to join other recruits, then those bound for infantry would take another bus to Fort Benning, Georgia, where we would swear to uphold the United States constitution and begin basic training. He showed me my contract, and asked if I understood. I had no questions.

According to delayed entry requirements, I had to demonstrate ten pushups.

I asked if he’d like them one-handed.

He said that wouldn’t be necessary.

I was a bit disappointed. To compensate, I did the mandatory ten pushups on the two punching knuckles of each hand (effortlessly, I’d like to add). I stood up with a smile and signed my contract with a flared squiggly-looking thing at the end of Partin; it was a new thing I was trying, a way to differentiate it from the other Partins and my dad’s neat and methodical handwriting.

The recruiter reminded me that the contract wasn’t binding, that I could change my mind all the way up until I reached Fort Benning, and even then up until I swore an oath to uphold the constitution of The United States of America. I thanked him. But, I said, I doubted that would happen.

Lea and I left the recruiter’s office and finished listening to Appetite for Destruction on the way to my orthodontist’s office. I had set up an afternoon appointment to have my braces removed even though I was supposed to wear them at least another year. When he asked what Wendy would say about that, I unfolded my paperwork and held it up like an FBI agent flashing a badge.

I knew the braces were expensive, but Wendy had already paid for that year’s service, which would include removing them. They were uncomfortable every few months when the orthodontist tightened them, but that wasn’t the reason, I told him. I said it was hard to breathe when wrestling, because I wore a silicone mouthguard to protect my lips and I wanted to wrestle without them my final year. He said okay, and two hours later I was free from braces.

I hopped back in Lea’s van and flipped down the sunvisor with its mirror on back. I checked my teeth for white squares where metal had been glued for three years. I had smoked my 10th grade year, and had heard stories of kids getting their braces off with grey stains around white squares, but my teeth showed no evidence of their past. I flipped the visor back up and smiled an exaggerated grin and nodded my head to let Lea know I was ready. She started the van, cranked up the stereo, and pulled out of the orthodonist’s parking lot with a spin of the tires that kicked up loose gravel.

Lea was prone to dramatize things. Her nickname was Princess Lea, like the character in Star Wars. Two months earlier, she had graduated from Scotlandville Magnet High School for The Engineering Professions, 40 minutes north of Baton Rouge if you drove, or around an hour and a half if you took the school bus. Lea’s dad gave her the van when she was 16 to make the commute easier for her, and we had been dating since her senior year at Scotlandville and my junior year at Belaire. Though far away and without a wrestling team or notable football team, the engineering program was renowned; famous alumni include the guy who invented the Sim City video game franchise, which was already popular in the late 80’s, and Stormy Daniels, a Baton Rouge Gold Club dancer who would become a household name nationally when she accepted an out-of-court sexual harassment lawsuit against President Donald Trump.

Lea’s eccentricity led to her being perceived as dramatic, which was probably true. She was a patient of Dr. Z’s, who prescribed her a mood-stablizing medication. She had already had an epileptic seizure, which, by law, meant she shouldn’t be driving, but Dr. Z was notorious for not filing out state-mandated paperwork on his patients.

To Lea, everything was a metaphor. She said removing my braces was symbolic of removing the shackles of my family.

I disagreed. I said it was harder to breath when wearing a mouth guard.

She liked her version better. She said one day I’d see it her way.

I said I saw the metaphor but only I knew what was true for me. I smiled an exaggerated toothy smile, and said I knew I was anxious to try out my lips’s freedom regardless of why it happened.

We parked along the levee in front of the old old state capital, a building built like a three-story castle and perched on the tallest hill in Baton Rouge, a forty foot mound of dirt overlooking the Mississippi levee that’s only a 100 yards rom the new capital. We hiked up the hill and sat under the sprawling moss covered branches of an old stately oak tree, took deep breaths, and sighed peaceful sighs.

She had a small hardshell Igloo cooler with a six pack of Milwaukee’s Best she had bought to celebrate, more for the joke of calling it Milwaukee’s Beast than any appreciation of craft beer. President Carter signed the bipartisan bill to legalize home brewing in America in 1979, but it was slow to catch on, and Abita beer from New Orleans was more expensive than any of my friends could afford. The Beast was an old friend; but, I had stopped drinking the year before to focus on wrestling.

Lea knew that, she said. She just liked beer, because she recently turned 18 she enjoyed flashing her ID to buy it.

She brought a Coke for me, but I told her I had given up sugar, too. Back then it was still made with sugar instead of the even worse for you high fructose corn syrup, and I had just learned to differentiate between simple carbohydrates and the complex carbs I used to load up before cross-country races. She shrugged as if I were free to choose whatever I wanted, even if it were as odd as not drinking Coke in the south, where it had been invented and practically poured into our bottles as babies.

She poked a dent in her Beast can just below the opening, so slow the flow of beer as she drank, and I sipped water from my dad’s old boy scout canteen that I carried in my school backpack. It was leftover of his that I uncovered at my great-great Grandma Foster’s house earlier that summer; he had lived there for a year before meeting Wendy.

Princess Lea sipped her Beast and I explained the difference between simple and complex carbohydrates. She listened, not because she was interested in carbohydrates, but because I was in a good mood and chatty and she loved me.

Lea knew I had always felt at peace sitting on the mild slope of the old state capital. PawPaw had taken me there to slide down the hill on a flattened cardboard box, just like other dads did with their kids, and my body recalled those years of happiness every time I revisited the slopes. I had pointed it out every time, and we were trapped in a positive feedback loop that neither of us minded.

In his autobiography, Life on the Mississippi, Mark Twain called our old state capital the worse eyesore on the Mississippi River; but, unlike that cranky old man who grumbled about most things, most people I knew adored it. To us, it was our cherished castle on a hill. Like you could see from the state capital, all of southern Louisiana is flat; many parts near the river are a foot or two below sea level, as if the only place to slide down something was into a muddy ditch beside the levy. It rarely snows in Baton Rouge, but as kids we would pretends we were snow sledding down a mountain by sitting on pieces of cardboard boxes and sliding down the 30 or 40 feet of grass hill in front of the castle. It was – and is – a Baton Rouge icon, though less revered than Tiger Stadium or the new state capital.

I don’t know what Mark Twain would say if he saw the billowing smoke stacks of petrochemical plants called Chemical Alley a few miles downriver from the two capital buildings, but I grew up knowing nothing else and didn’t notice them. I only saw the old castle and the new capital and the Mighty Mississippi River, with all of its barges passing under the Mississippi River bridge and all of the Teamster 18 wheelers rumbling overhead.

I didn’t know that only a mile behind us lurked Hillary, probably running up and down the new state capital stairs again and again. I had, in all sincerity, just began thinking that I’d shoot for becoming state champion, like that guy in the movie Vision Quest. It was just a thought that began itching at the back of my mind as soon as I walked out of Judge Bob’s office. I didn’t know Hillary yet, so there was no known challenger to my hero’s journey, but the idea of winning state had been planted in my mind at the recruiter’s office and sprouted on the banks of the Mississippi River that evening.

I mulled over the new thought in my mind and stared across what, to us, seemed like an ocean. The Mississippi is about a half mile across, with the small river port town of Plaqumine barely visible on the other side to our left, and miles of sugar cane and farm land to our right. We had our own private ocean view. Late summer sunsets were always the most colorful time to be there, especially when the murky Mississippi River water softened glare from the setting sun and made the sky seem like a smooth transition from red to orange to lingering hints of blue dotted with white clouds. We both sighed.

Lea finished her beer and another cigarette. Dusk settled, and we found a giant old stately oak tree with enough gnarled branches to get privacy from the few people walking by on a weekday. She was a snuggler after a few beers, and I cradled her and we chatted with our faces only a few inches apart.

“Coach gave us marriage advice,” I said, practicing talking without braces. My lips felt loose; I had to concentrate on not spraying spittle when I talked.

Lea raised a dark eyebrow over her narrow eye. She was half Japanese, though most people assumed she was Creole, the mix of Spanish and French aristocrats with the slaves that remained every time Spain and France swapped ownership of Louisiana. Creoles were so common in southern Louisiana that no one ever had a reason to ask Lea’s background.

I held up my finger the way Coach did when he was saying something important, and said:

“He held up his finger and said…”

I changed my voice to mimic his raspy midwestern accent, slowed my speech, and continued:

“Gentlemen. The secret to a happy marriage is: no matter what type of day you had, the first thing you do when you get home is kiss your wife on the cheek and ask her how her day was.”

I lowered my finger and Lea cocked her head as if expecting more.

“Why’d he say that?” she asked.

I said I wasn’t sure.

“He was in a good mood all day,” I said. “I think it’s his anniversary this week or something like that. He was smiling like a kid in a candy store all day. I think he and Mrs. K had a date night.”

“Hmm,” she said. “That must be nice.”

Not all of Coach’s advice applied to everyone. To Lea and me, asking about someone’s day was invasive. It forced them to lie. Though I was still mid-pubescent, for almost a year we had been fooling around and I ejaculated a bit, but none of her friends knew the details or that I had scraggly public hair. And I never told anyone her mother was Japanese, or that Lea had developed her great boobs young, and that at 12 years old she was raped by an older boyfriend who had a car and seemed cool at the time. When we talked about it, she thought that was why she liked younger men.

“We had a bunch of kids from Belaire Middle over,” I said. “Some from the shows I did. I was showing them some basics and invited a few guys from the team to meet us. Andy and Timmy showed up to help. They hadn’t found jobs yet, and Coach told all of us how any of us could earn a living.”

Lea raised an eyebrow. I changed back to my midwestern accent, held up my forefinger, and said: “Pig Farming.”

Both of her eyebrows went up in a mix of confusion or curiosity.

“Pig farming,” I repeated, just like Coach had. It had pricked our curiosity, too.

“They don’t need a lot of attention,” I said, still using a poor impersonation of Coach’s accent. “But if you treat them well, you’ll be happy in life.”

We mulled that over silently for a while.

Eventually, she smiled and said: “They’re just like me.”

We giggled and snuggled more closely.

With her face pressed beside mine, we stared between the leaves at the barges floating up and down the river, and she said, “Tell Andy and Timmy I said hi. I won’t see them at Todd’s before school starts up in two weeks.”

She was enrolled in Southeastern an hour away in Hammond, planning to major in theater and physics. I made a sound that told her I would, a kind of “ah-huh,” and we both sighed peacefully and watched barges float down the river in no hurry to be anywhere else.

It was August and the days were long. We sat facing east, and watched the clouds across the river slowly colors from a sun setting behind us that we never saw as kids, because we always stayed on our side of the river. At dusk, we found an oak tree with exceptionally dense branches undulating across the ground that made a nook inside, fooled around, and went home to her family.

We ate take-out pizza dinner and to watch Everybody’s All American on their VCR to celebrate my day. Her younger sister, Robin, was there with a newborn who slept through most of the movie. Her dad had worked on the set and had met Dennis Quaid, something he said every time we watched it, and we had a game of trying to glimpse Lea in the crowd scenes. Robin picked up one of her dad’s magnifying glasses, and thought she could see Lea, though none of us were sure because the crowd scene pixels were so blurred.

Everybody’s All American linked Baton Rouge to Big Daddy in my mind. It wasn’t just that he was portrayed as an all-American hero, it’s that, though he was in prison at the time, he brought Everybody’s All American to Baton Rouge in 1985.

Hoffa funded a lot of Hollywood films in the 1950’s and 1960’s using the untraceable and untaxed $1.1 Billion Teamster pension fund, one of the many things that put then Sentator John F. Kennedy, chairman of the U.S. Labor Commissions Committee, in pursuit of Hoffa. The mafia also benefited, and Hoffa had lent out around $121 Million to different families in the 60’s to build casios in Las Vegas, hotels in New Orleans, and different projects along the Jersey Shore; all of those projects used Teamsters to haul materials to and from ports, but not even the Kennedy’s knew all of that back then. The Hollywood films were more obvious; if you sit through the credits, the final screen is a huge Teamster logo, a ships steering wheel framed by two horse heads, Thunderbolt and Lightening, the two horses who were the mascots of Teamsters from before trucks, when products were shipped by horse wagons. Big Daddy came to power in the late 1950’s, and he brought big Hollywood names with by using Hoffa’s influence.

Under Big Daddy’s reign, John Wayne was in town for civil war movies filmed using the nearby plantations as backdrops. An actor of that caliber, especially one who was 6’4″ and known for his rugged and handsome looks, sparked everyone’s interest; not because he was John Wayne, but because Big Daddy was a new and seemingly permanent part of Baton Rouge, and he was bigger and more handsome than John Wayne. From the time The Horse Soldiers was filmed until Big Daddy went to prison in 1980, practically any film wanting to recreate that era used Big Daddy’s Teamsters, and people began getting work they never imagined possible in Baton Rouge. Big Daddy became bigger than John Wayne to most of my schoolmates’s parents.

By the 1980’s, other types of films were being shot in Baton Rouge, but they all began as negotiations with the local Teamsters over a few years before filming began. A lot of kids at school had parents who worked on the sets, and aspiring actors and actresses vied for roles in crowd scenes. Even people from New Orleans would drive out to audition.

You can see Lea in a crowd scene of 1985’s Everybody’s All American. It starred Dennis Quaid, Jessica Lange, John Goodman, and a host of other big name stars. Dennis Quaid was The Grey Ghost, a southern college football legend and an All American loosely based on LSU’s favorite All American Hero, Billy Cannon. Billy was the star of the 1954 National Champion Tigers, an All American, and a Heizman Trophy Winner; he went on to play pro ball in Houston, then, like the classic hero’s journey conclusion, returned to Baton Rouge and went to dental school and opened an orthodontist office. You could see his smiling face from atop Lamar billboards up and down I-110, and the joke was that in Baton Rouge, Billy was more famous than Dennis Quaid when they filmed Everybody’s All American.

All the actors stayed in Teamster trailers, and all the equipment was hauled across country by Teamster trucks. Lea’s dad was one of the Local #5 Teamsters who scored a plush role moving equipment around locally for each seen, so he had advance notice of timing for big events, like when 10,000 Baton Rouge people got to be in one scene recreating a 1950’s football game. You have to squint and use your imagination, but a lot of us swear we recognize our middle school friends, neighbors, and teachers in that scene. (I was, ironically, in Arkansas with my dad that Christmas, but I heard all about filming when I returned.)

In another crowd scene, everyone gathered around the new state capital for a 1950’s press conference celebrating The Gray Ghost. But it snowed that day, a rarity in Baton Rouge that everyone said was a miracle and made the scene magical, but the director decided to reshoot on a day more typical of the south; a magical scene would be out of character for the film, he said. Everyone in town donned their 1950’s costumes again, and gathered for a more typical southern football celebration.

Because of her dad’s role with the film crew, Lea was in both scenes. She was 13 then, though she looked much older. The filming experience led her to wanting to study movie making and to work behind the scenes as a set and costume designer, a practical combination for a hands-on tinkerer who avoided the spotlight.

Lea and I had shared everything about our families that we knew. Her dad had worked for Big Daddy on and off over the years. It seemed that half of Baton Rouge had, at some point in their lives, worked for Big Daddy, but only Lea and her dad told me stories about their experiences.

She grew up hearing of her dad’s exploits stealing building materials from construction sites all over the southeast, keeping parts of orders in the back of his 18 wheeler and brining them to Baton Rouge, where Big Daddy used them to build a NASCAR racetrack called the Baton Rouge International Speedway. It was later renamed The Pelican Speedway, and when investors showed up, Big Daddy gave away tickets to anyone in Baton Rouge who wanted them, just to pack the stands and create the image of sold-out events. To everyone in town, getting free tickets to NASCAR races was just another perk of having Big Daddy around.

Big Daddy’s plan worked, and investors paid the ostensible owner, a Teamster Big Daddy trusted or at least knew wouldn’t cheat him, a large but unknown sum of money for the race track and stands. Pelican Speedway soon went bankrupt, probably because Baton Rouge was mostly a football and baseball town with little disposable income for other ventures. The speedway was demolished to make way for a new subdivision in the mid 1970’s.

But by then all the Teamsters involved were paid well and no one spoke of the theft or deceit, except for a few like Lea’s dad who told her where his new van and their house came from. Twenty years later, Lea used that van to drive us around all summer. She had graduated Scotlandville Magnet High and would be leaving for Southeastern University an hour away in Hammond two weeks later; her dad radiated pride at that, because she’d be the first person in their family to attend college. He had a house that was paid for and health insurance to treat both his daughters, and to him my family could do no wrong.

“Any grandson of Edward Partin is welcome in my home,” he told me, adding a grin that implied he hoped to one day be my father in law. The thought had crossed my mind.

Their home was a cluttered mess of old Little Caesar’s two-for-one pizza boxes and piles of partially completed projects, like a life-sized Klingon battlith from Star Wars The Next Generation, several Renassaince costumes including a chain-mail version of Princess Lea’s slave outfit, and a few boxes of what was then science-fiction looking remote control cars and airplanes. Her mom rarely left the house and her dad had been on disability since the late 70’s and rarely ventured out, either, except to find parts for car projects that never seemed to be near completion. He was an amateur engineer and physicist, and had worked for Big Daddy when he got out of the navy doing nothing but hauling construction equipment for big companies all over the southeast.

He was injured in a way he never described, and Big Daddy’s forceful method got him a worker’s compensation package from a construction site accident. Other than the Everybody’s All American gig, where all he had to do was sit in a trailer, he hadn’t worked for a paycheck since his accident settlement. But, he stayed busy with countless projects, and he radiated gratitude for that opportunity. He didn’t understand why I’d want to emancipate from them, but he never asked questions and only talked about his time with the Teamsters with positive things to say.

“He never drank,” he said of Big Daddy, with an obvious tone of respect. In Louisiana, where a board member of Budweiser was a legislator and we had no tax on alcohol, not drinking booze was more rare than not drinking Coke.

“Never,” he reiterated. “He said it loosened lips.”

“I haven’t drank since,” he said with the tone of someone who used to drink too often.

He leaned in and whispered to me, “He was really good with a knife.”

I knoded that I knew that. I said he skinned his own elk and deer, and had taught me how to keep a knife sharp to make the work easier. Lea’s dad leaned back and smiled, happy to have shared a bit of his past with someone who knew. It’s hard to keep tight lips. Lea was one of the best at it; I sometimes slipped and said things like I had about Big Daddy’s knife.

To get to her room, Lea and I had to step over piles of clothes that were patiently waiting for a laundry day that probably wouldn’t happen soon. Once inside, we had to crawl over her piles of clothes and a cage with her two pet rats, Meth and Amine.

“They’re very social,” she told me. “It’s cruel to keep one by itself.”

She lowered her tone, which meant she was angry, and said, “Any pet store that doesn’t sell you two should be banned.”

She took them out and we pushed clothes off her bed and let them snuggle on our chests while we sat silently.

“Uncle Bob would be proud of you,” she said softly.

My normal Partin smile vanished faster than Jimmy Hoffa in a Detroit parking lot; my jaw tightened and my eyes squinted. I had broken down giving his eulogy and cried for the first time since 1983; a month later, I wasn’t doing as well as most people assumed. I took a few breaths and my jaw loosened.

“He kept the card you gave him,” I said.

She laughed and said, “I thought of him as soon as I saw it.”

It was a simple card with a cartoon lemon on front; inside, it said, “When life gives you lemons, make whiskey sours.” Uncle Bob was the most cheerful alcoholic you ever met. Until his chemotherapy and radiation treatments at age 64, he hadn’t been sober a day since he was 14 years old. To the end, he kept his humor and that card. Lea had visited me, and therefore him, at Our Lady of the Lake a few late nights leading up to his hospice at home.

Though his obituary was in the paper, it missed a lot of details. The Baton Rouge advocate didn’t say that Uncle Bob had obtained his American citizenship the year before he died, and they didn’t mention that he had served in the Canadian navy during WWII, or that he was manager of the New Orleans branch of Montreal’s Bulk Stevedoring for thirty years. No one but Auntie Lo and I knew that while he was dying at home, former employees drove up just to see him and thank him for being a good person and running a simple yet effective office.

Bulk Stevedoring was responsible for loading and unloading cargo freighters to and from all over the world, and Uncle Bob traveled to China and South America to negotiate the contracts; he could raise a toast in twenty different languages, and make a cocktail from almost any local booze he could find. He had retired only two years before his death at age 64. Practically every year for my birthday and for Christmas, even though I was rarely in town, he and Auntie Lo asked which magic book I wanted, and it showed up under their tree or in my room, the same room they had kept for Wendy when she was my age. Though they never had children, they treated Wendy and me as if we were gifts that they cherished.

I had given Uncle Bob’s eulogy, and I had wanted to say all of that and more at his funeral. But I broke down after telling his favorite joke, that he wanted me to hire a U-Haul to tow behind his hearse, just so his neighbors could say that he died taking everything with him; no one laughed. I began bawling and couldn’t stop. It was about two minutes before I stopped crying enough to be guided from the podium and back to my seat in the front row. That’s the length of a round of wrestling, about as long as I can go without breathing normally, and when I sat down I drank deep breaths of air and tried to keep my eyes open. Auntie Lo, who was drunk even then, was crying so hard she collapsed into my arms and I hugged her and used that to stop my own crying.

That was only a weeks earlier. I hadn’t processed Uncle Bob’s death yet, and neither had my mom, but we were probably both too young to realize that.

“I’ll never forget what he told me,” Lea said, brining me back to the present.

She said, slowly and with a calm, definitive tone: “I’ll die without regrets.”

My jaw tightened again and my shoulders trembled. Lea leaned into me and we were silent for a few minutes.

I took a few shallow but intentional breaths, then reached over and gently tapped the glass cage of Meth and Amine. They sniffed around, expecting food or affection. I thanked Princess Lea for a glorious day. It wasn’t as eventful of a day as Ferris Bueller’s Day off, I said, but I bet it was the best first day as an adult any 16 year old had ever had. If Mark Twain had days like ours, I said, maybe he would have appreciated the old state capital more.

She agreed. We snuggled all night long. It was, despite all what had happened, probably the happiest day of my life; or, at least the happiest day of my adult life so far.

That weekend, Lea’s mom showed me my name in The Baton Rouge Advocate’s weekly court summary. They used my entire name, perhaps to lesson confusion with my cousin. The newspaper said:

Jason Ian Partin was emancipated by Judge Robert Downing of the East Baton Rouge Parish 19th Judicial District, and has all of the privileges entitled by emancipation.

I clipped the blurb out and used a paper clip to hold it, my emancipation proclamation, and delayed entry contract together. Lea scrounged around her room and found a manilla envelop to keep the together and professional looking. I carried them in my school backpack, mostly to be practical in case I had to prove I was an adult for any reason, but also because I liked seeing my name in the paper without association to either of the Edward Grady Partins.

The most telling thing about becoming an adult, though, was the absence of my Fun section clip-out in the growing folder that documented my transition to adulthood. I wasn’t going to be doing any magic shows in Baton Rouge again, because wrestling would take up all of my time and then I’d head off to the army. And the photo was old. I still had my braces in it. Though I didn’t admit it to Lea, I began to suspect that she was right; the kid in that photo was a different person. Perhaps I had removed the shackles of youth. The only things in my folder were practical pieces of paper, the contracts I signed without my parents’s approval and my guarantee to leave Louisiana when I graduated. Project Magic would have to wait.

I kept the article to use with my senior year scrapbook, along with Uncle Bob’s obituary, but I threw away the postcards from my dad. Going forward, I told myself, I was a new man. I wanted to live without regrets, and that meant giving everything I could muster to the 1989-1990 wrestling season.

Go to the Table of Contents