Wrestling Hillary Clinton: Part III

Partin Reign May be Short-Lived

Edward G. Partin, start witness in the trial of Jimmy Hoffa, is now reigning supreme over the Teamsters in central Louisiana.

‘I’m not going to have Partin and a bunch of hoodlums running this state,’ Gov. McKeithen told us. ‘We have no problems with law-abiding labor. But when gangsters raid a construction project and shoot men up at work I’m going to do something about it.

‘Partin has two Justice Department guards with him for fear Hoffa will retaliate against him,’ Gov. McKeithen said, ‘This gives him immunity.’

The governor referred to an incident in Plaquemine when 45 to 50 men shot up 30 workers of the W.O. Bergeron Construction Co.

“Baton Rouge has never has such a siege of labor violence as it’s seen since Partin came back from the Chattanooga trial with two Justice Department guards to protect him.”

New Orleans State Times, 27 January 1968

Coach didn’t know it, but when he lent me his keys to Belaire’s gymnasium and offices I made copies for myself.

He lent them to me so I could wheel the massive boulder of a television set and the VCR machine it rested on from his shared coach’s office and into the gym we shared with the basketball team. I wanted to show Vision Quest to new wrestlers at the first day of practice. He wanted to watch it first, and he told me he’d meet me after school. It was just before lunch, and I skipped school and jogged over to Little Saigon, where I knew a shop that had a key making machine.

Like Baton Rouge, Southern Vietnam was a hot and humid seafood-producing region and had been a French colony. When Saigon fell in 1975, hundreds of Vietnamese families fled and settled in, of all places, Belaire subdivision. They worked in our seafood industry and to set up shops in strip malls along Florida Boulevard, far enough from wealthier subdivisions that rent was cheap and regulations were lax.

Their shops were known to sell practically anything. They were industrious, classic examples of what Americans touted as hard working, but they weren’t accepted by the working class families around Belaire back then; it was probably too soon after the Vietnam conflict. One Halloween, a local Vietnam conflict veteran with PTSD (post traumatic stress disorder, though it was still called shell shock or battle fatigue back then) shot a Vietnamese kid who knocked on his door one Halloween and was, ironically, trying to blend in by dressing as a GI Joe soldier and trick-or treating like America kids on TV. Several other shootings made the news, and Belaire became known as an undesirable neighborhood.

For some reason, white families blamed the Vietnamese for violence around Belaire and had begun moving away. Houses became cheaper, and the neighborhood gradual changed and grew to be ignored by police patrols, who focused on downtown and answering calls in wealthier subdivisions fighting against change. I briefly lived in a house across from Belaire High one summer the late 1970’s, only four years after the last American troops left and Saigon fell.

My dad knew the area had hardly any police and a lot of inexpensive three-bedroom, two-bath rentals where he could store and dry piles of marijuana plants to sell around town. One house was across from Bealire, where I used to help him pack plastic sandwich baggies with 1/8th ounce of week, plus a little extra, called Lagniappe in Cajun French, a little bit extra tossed in for generosity, similar to a baker’s dozen but done without expectation. Uncle Kieth, my dad’s little brother, lived with Aunt Shannon in a trailer park a few blocks down from Little Saigon on Florida Boulevard, and he would sometimes swing by to say hello and pick up a dime-bag from my dad. I grew up knowing Belaire subdivision better than any part of Baton Rouge other than the old and new state capital grounds.

Though none of us interacted with the Vietnamese community, we all shopped at their stores. I especially liked the Bon Migh sandwhiches made with their version of French baguettes, advertised by a hand-written sign that said: “Bon Migh (a Vietnamese Po’Boy),” and while my dad or Keith were buying beer I’d glance in windows and learn about a culture so foreign to me I might as well have been peering through bars at the Baton Rouge zoo.

Besides Vietnamese Po’Boys, the Little Saigon shops sold practically anything to anyone. Teenagers could buy cigarettes and bootleg cassette tapes, rent porn, and have keys copied despite “do not copy” being engraved on the original. Ironically, they also sold t-shirts and hats that catered to American veterans and teenagers who looked up to them, shirts with skulls wearing the beret of Airborne berets and sprawling, elaborate letters that said: “Death from above,” or some with a skull and beret with criss-crossed M16 machines guns and plain letters that said: “Kill ’em all, let God sort ’em out.” To cater to LSU fans, they made a shirt with Death Valley and the phrase: “Though I walk through the valley of death, I shall fear no evil because I’m the baddest mother fucker in the valley.”

In the middle of the day on any weekday, where most adults were at work, you’d see bearded veterans wearing those t-shirts or faded green army fatigue jackets, smoking cigarettes both inside and outside of a windowless bar in Little Saigon’s strip mall. Beside the bar was an arcade that sold single cigarettes for a quarter, and we’d skip school with a handful of quarters and make our mark on the world or to save it by playing Space Invaders and Galactica and stand outside with the vets, who would often buy us beer and share their philosophies on succeeding in life. Those lessons stuck with me when I would join the army six years later, which probably sparked my scoffing the slogan about being all you could be.

I was the best video game player in Belaire subdivision, but the 16-bit screens only held three letters. Shortening Magik to Mag didn’t sound right, so I entered my birth initials to leave my mark on the world, and no one knew the real identity of JiP, who held the top score in Centipede and Donkey Kong. When games began accepting up to six letters I used JipBit, a play on the new 32-bit and greater video games, and funnier to me than using Magik. Besides, I knew that if my teachers called me Magik, it would be hard to explain how such a unique name was so well known in the arcade; that’s why in 1989 JiPBit held the record on Galicia and Zaxxon in Little Saigon.

I didn’t play video games or linger with the vets on the day I copied Coach’s keys. Instead, I jogged back to Belaire before anyone would notice I was gone. That afternoon, in the same time slot already allocated for wrestling practice when season would begin, Coach and I watched a bootleg copy of Vision Quest together.

Vision Quest was barely known outside of wrestlers. It paled in comparison to the box office success of similar movies like The Karate Kid, Rocky, and of course Star Wars. All mainstream movies seemed to be versions of the heroes journey that dominated films after 1979’s Star Wars, and George Lucas generously shared the formula he learned from the book, “The Hero With a Thousand Faces,” which analyzed myths, legends, and stories throughout history. In the heroes journey, a young man, usually an orphan or an otherwise unremarkable young man, meets a mentor and trains to overcame a stronger opponent, then returns to help others do the same.

But Vision Quest was different, because the protagonist lacked a mentor and was self-motivated. It spoke to me the first time I saw it at The Abrams house on their laser disc system, and soon after I bought a VCR version in Little Saigon. I don’t recall the price, but it was probably only $2 or less, much cheaper than an official version and within walking distance rather than a twenty minute drive to Cortana Mall.

Vision Quest was quickly forgotten in the wake of other films, but its saving grace was that it stared Madona before anyone knew who she was. She sings the song “Crazy for You” in a small town bar that the hero and his older girlfriend slow dance to. When she became famous, Vision Quest was rereleased and advertised as a movie “staring Madona,” which is probably why Coach wanted to watch it before letting me show it to the freshmen.

Soon Madona sang that song, the wrestler and his girlfriend drove off and fooled around in a discrete scene; the sex was downplayed because the wrestler emphasized having burned 150 calories and said it was a great way to cut weight. It was how a wrestler would think.

Vision Quest was based on a book by the same name that I read after watching it. The film followed the book closely, but was changed to be a bit sexier and sell more tickets. John Irving, the famous author whose book was made into The World According to Garp in 1982 and starred Robin Williams as Garp, a high school wrestler who becomes a coach, said Vision Quest was the best book about wrestling ever written; Irving, a high school wrestler who, despite being a famous author, still coached a team in Virginia, was in the USA Wrestling Hall of Fame and a household name in the 80’s. But even with that endorsement, Coach wanted to watch it before lending me the VCR to show it to the team.

It took about an hour and a half, the time we were about to both start staying after school for practice, anyway. In that brief time, we saw a condensed version Lauden’s senior year and all of the lessons he learned, like how to stop a nosebleed, counter a chicken-wing, and how to cut unhealthy amounts of weight in a short time. And because Lauden was studying for medical school and talking about what was happening with his weight loss and sexual urges, we learned – or at least memorized – a bit of biology, too.

Coach nodded and said it would be fine to show Belaire’s kids, though not the middle schoolers. Typical of almost everything Coach said, he never mentioned Vision Quest again.

We wheeled the massive television back into the coach’s shared office. He reached up and clasped his hand on my tricep and began walking towards the football team’s weight cage. Coach’s grip was like a thick steel vice locked on my arm, and I followed without much choice.

“Listen,” he said when we reached the cage. It shared a gym with the basketball and wrestling teams, and Belaire’s faded blue mat was in three sections and rolled up against the wall so basketball players could use the full court. The cage was locked during school so no one would use it unsupervised. He paused to pull his keys out of his sweatsuit pocket.

He opened the padlock, swung the gate open, and locked the gate against the cage so it couldn’t accidentally swing shut. He put his left hand on my shoulder again, raised his stubby right forefinger and looked up into my eyes.

He had soft grey eyes that matched his whispy hair, and I saw a tiny bald spot forming atop a head so flat you could rest a can of beer on it. His finger was about a foot from my face, and his stubby arm bulged with muscles like Popeye’s. He held eye contact silently for a few seconds while his lips moved a tiny bit, as if he were chewing on what he wanted to say before spitting it out.

He said: “If you’re going to be co-captain, I’d like you to earn at least a B average.”

I nodded and said I’d try my best. Coach nodded back and released his hand. We never spoke of it again.

State law required varsity athletes to maintain a C average, and most star athletes I knew were given grades to keep them playing. I had failed about a third of my classes in ninth grade and a few in 10th, around the time my dad and I were hauled out of his cabin by armed deputies, and my grades were only part of why I couldn’t wrestle that year. I was also suspended for using vulgarity in school, though I don’t recall what I said and was probably just repeating something my dad and I joked about all summer. Like all kids, I parroted what I heard at home, so I probably called Ronald Reagan an asshole.

I rejoined the team my junior year and barely earned a C average, and that was with repeating classes I already taken but failed in 9th and 10th grades. I never saw the point of school. Both of my parents had dropped out in 11th grade, and Big Daddy never obtained any degree yet was the most powerful man in Louisiana. Newspaper pundits and the state attorney general said, “If Edward Partin had a college degree, he would be governor,” which was funny to me because Governor McKeith said Big Daddy ran the state.

In 1980, Big Daddy was finally in prison, and the Louisiana Teamsters voted to keep paying him and keep him in charge, just like the International Brotherhood of Teamsters had kept Hoffa in charge from prison when Big Daddy put him there. From his cushy celebrity cell, he offered to endorse John Edwards as governor; Edwards was already famous for having been governor a few times and being impeached and going to jail and never completing terms, yet being re-electected again and again. He accepted a check for $400,000 to look after gambling interests in Louisiana just before he pushed legalizing gambling in Louisiana and started floating Mark Twain era looking riverboat casinos in Baton Rouge’s port, giving people jobs and entertainment, just like Big Daddy had done and therefore he could do no wrong in Louisiana.

Edwards was so popular that in 1980 he told newspapers the only way he wouldn’t be re-elected was if he was caught in bed with a dead hooker or a live boy, and that he wouldn’t accept my grandfather’s endorsement because Big Daddy was too controversial of a character, the equivalent in Edward’s mind of being in bed with a dead hooker or live boy.

As Walter Sheridan repeatedly pointed out, sometimes sounding confused but ultimately accepting, Louisiana has colorful politics, and no wrong seems unforgivable, especially if it gets people jobs. Edwards lost that election, but he ran again in 1984 when Big Daddy was still in prison but Uncle Doug was running the teamsters. He must have learned from Big Daddy, because accepted Uncle Doug’s endorsement and won. He would bring legalized gambling to Louisiana and then serve time in prison when prosecutors proved he accepted bribes by casino owners to bring legalized gambling to Louisiana. Edwards would serve as governor four times, possible despite the law that says you can only complete two terms because, technically, his times in jail and impeachment prevented him from completing two of his terms.

Despite my apathy towards anyone in authority, or perhaps because of it, the Belaire wrestling team voted me co-captain at the end of my junior year. The honor of my team electing me co-captain, a role with twice the responsibility but no authority, motivated me more than any future goal. But that’s only part of why I was helping recruit middle schoolers to build our freshman team. Mostly, I was just listening to Coach.

Because Coach was a man of so few words, I listened to everything he said. He had told me about Skip Bertman, LSU’s legendary baseball coach and athletic director recruited to LSU soon after wrestling disbanded and Coach started a team at Belaire.

Skip is legendary. He led LSU to win 5 college world series and seven southeastern championships and put LSU baseball on par with football, both nationally and with a support network of parents showing up at home games for baseball the way Capital High parents packed their bleachers for wrestling. He was doing that, Coach said, by walking door to door in all Baton Rouge neighborhoods and recruiting young kids to start baseball camps, and then encouraging parents to participate. He said that’s why Iowa was the nation’s powerhouse of wrestling, and Skip was doing the same thing for Louisiana baseball.

I was already used to going door to door and doing a few tricks in hopes of getting magic shows, so I went to Belaire Middle’s graduation and recruited 8th graders who would be starting at Belaire in the 9th grade. Instead of coins and cards, I wore my Belaire hoodie and spoke of Coach and teamwork; wrestlers compete as individuals but train as a team, I said. And they must maintain grades, I said. It’s the best of all worlds. When asked, I said I was just a wrestler who loved the sport; I didn’t say I was co-captain, because it would take too long to explain in a culture where one person is idolized. People wanted to hear about Skip Bertman, Governor Edwards, or Huey Long, not a lesson on democracy, so I told them about Coach.

I told middle schoolers I was voted captain, not co-captain, not to lie but to simplify the story and get to a point, because of something

Coach said one day my sophmore year. I was ineligible to wrestle, but I was allowed to participate as a “Red Shirt,” a person who can attend practice and support the team but can’t compete. I told the kids I’d go to dual meets hosted at Belarie, and my girlfriend (who was Lea, but I didn’t tell the kids her name) would drive down from Scotlandville to join me in the bleachers. One time I was sitting with her midway up the bleachers, with my baseball hat cocked to the right side. Coach strolled up the bleacher steps and smiled at us and slowly crept his hand to the bill of my hat, then slowly rotated it forward. He smiled and winked to let Lea know he was teasing, and said I should be able to see the mats better with my hat pointed towards them.

He walked back down and Belaire didn’t fare well. It was still only the third or fourth years since more than two kids had shown up. After a few losses, Coach came up to Lea and me again. His tone was uncharacteristically serious, and he asked me: “Why are you here?”

“To support my team, Coach,” I said.

He looked me in the eyes, held up a forefinger between us, and said:

“No you’re not.”

He pointed to Lea and said, “You’re up here with this lovely young lady, talking with her.”

He kept his gaze locked to my eyes, but twisted his body and pointed down towards the mat and said: “If you want to support your team, go down there and support your team.”

I did. Lea sat with me on the first row bleachers, and I leaned forward and rotated my cap backwards so I could simultaneously see both the mat and the roof-high basketball scoreboard we used to keep score for each match. I began doing that at all Belaire dual meets.

Any kid of any size can wrestle, I told the middle schoolers. All you have to do is show up and support your team, and you’ll do fine.

I listened to whatever Coach said. I didn’t always do it, but I thought long and hard about why he said things before making my choice. He had said he’d like me to earn a B average, and I said I would try. I didn’t listen to every aspect of his advice, like sitting in the front rows so the teacher’s new you were trying, a version of sitting next to the mat to show support. My aversion to authority was strongest sitting and listening to a teacher, and, personally, I was unconcerned with whether or not I had a B or a C.

But I had told Coach I’d try my best, and my best meant doing whatever I needed to sit still in class. On a whim, and I still don’t know why I did this because I didn’t take time to think it over, the day after Coach asked me to earn at least a B average I walked into the vice-principal’s office and asked him to waver me into physics and calculus classes.

Mr. Vaughn, a man who was overtly against teacher’s unions and therefore probably not a fan of the Teamsters or my family, asked why. I told him what Coach said and that I had joined the 82nd and that I felt he was right – perhaps I wasn’t being challenged in classes. I had failed geometry and trigonometry and would have to repeat them my senior year, and they requirement for physics and calculus, but I told Mr. Vaughn that I had told Coach I’d make a B average and he trusted me. And, privately, I knew Lea was taking Physics 101 at Southeastern and that I’d have an excuse to spend time with her studying.

He agreed. Unlike Coach, who never asked about anything he hoped for me, Mr. Vaughn would begin checking in on how I was doing in physics and calculus every week or two. There’s no spoiler here: I’d later become a university engineering and physics facilitator (I’m adverse to the words teacher or instructor, and not at the level to be called Coach), and I invented a lot of medical devices that relied on physics and calculus in early design sketches, so whatever Mr. Vaughn did must have worked. I barely noticed what he did because my focus remained on wrestling.

It was because of Coach that I grew to have the strongest cradle in all of Southern Louisiana, and that began the summer in between my junior and senior years of high school.

When Uncle Bob got sick and Auntie Lo was too sloshed by 3pm every day to drive me to and from practice at summer camp, Coach found a compromise. He didn’t take me to camp, but he took me on errands to different wrestling programs all over southern Louisiana. Once a week, Lea would pick me up and drop me off at Belaire, where Coach would pick me up in his old brown Ford 150 pickup truck, the one we knew well from helping him load rolled up wrestling mat sections and shuttling them between schools for tournaments in winter and spring. But in summer his truck was filled filled the truck with mops, 5 gallon buckets of fungicide, and bags of off-white headgear that he bought in bulk and dropped off at schools with even less of a wrestling budget than Belaire, mostly smaller rural schools along the 80 mile River Road between Baton Rouge and New Orleans.

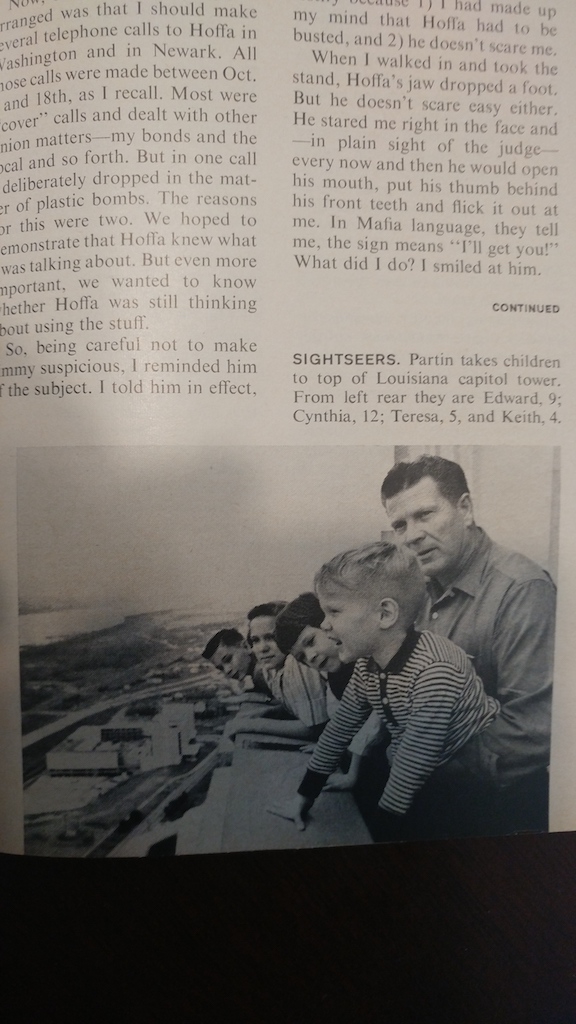

We’d stop at Region I schools like Brusly and Clinton and chat with their coaches, who were often former high school wrestlers or simply adults who signed up for the job and weren’t given much budget. I knew Clinton from family stories: that’s where Big Daddy and Mamma Jean lived when they first moved to Louisiana. (My grandmother, Big Daddy’s third wife, was born Norma Jean Tidwell, but everyone called her Mamma Jean.) Big Daddy and Mamma Jean crammed my dad, Uncle Keith, and Aunts Janice, Cynthia, and Theresa into a tiny two bedroom home before Big Daddy had enough cash in his pocket to buy a big house in Baton Rouge. Clinton was only a half hour away, but to them Baton Rouge was the big city with a booming economy, with rumors of petrochemical plants settling there and new roads being built by Teamsters.

The River Road was a working class stretch of road that made Belaire look privileged by comparison. Belaire had around 900 students, but these schools were so small that sometimes middle schools were combined with high schools and still only had 300 students, a few fewer than the size of Belaire’s senior class. And because schools are funded by local taxes from lower income working class families, those schools suffered from The Matthew Effect and had less than Belaire.

“I started a company,” he once told me on the drive, one of the few times he told me something I hadn’t asked.

The windows were down despite the muggy air blowing on our faces, but the noise was negligible because Coach rarely approached the speed limit when driving, and the speed limit was a paltry 45 along most of the narrow and winding River Road. His was also Belaire’s drivers education instructor, and like with wrestling he practiced what he preached when driving.

“A small company,” he said. He pushed the turn signal lever up and slowed down and got into the turning lane that would take us to Clinton. He stopped, turned, and continued.

“It let’s me buy equipment at wholesale prices,” he said. “They only sell to companies.”

He kept both hands on the wheel and shrugged and said, “I figured, with a company, I could buy more with the same amount of money.”

“That way,” he said, “I could give more schools what they need.”

We pulled into Clinton’s parking lot and he lowered the gear lever into park, turned off the truck, looked at me, and said, “Rising waters raise all ships.”

Growing up in a port town, that was probably the first metaphor that made sense to me. Phrases like “raining cats and dogs” were fantastic, and bromides like “work smarter, not harder,” were useless. But everyone rising simultaneously was clear. For years, I had sat on my perch by the old state capital and watched the Plaquemine docks raise and lower water, and I knew that all ships did, in fact, rise equally.

At every stop, Coach made sure a school had fungicide and mops and spare headgear for wrestlers, then we hustled off to the next school. Headgear was mandatory by then, but many kids would be too embarrassed to admit they couldn’t afford it and Coach didn’t want lack of a few dollars to stymy their future. And of course fungicide helps everyone, even visiting teams, so giving that away was like raising tides for everyone, one five gallon bucket at a time.

We drove the River Road with the levee on our left and houses on our right, and we took the take potholed roads that dipped into small towns and led to schools with only two to three hundred students total, often combining middle and high schools to share a building. About two and a half hours to three hours after leaving Belaire, Coach’s truck would be empty and we’d reach New Orleans and stop in St. Paul’s Middle School, a relatively wealthy suburb of New Orleans where Craig Ketelsen coached.

Craig was Belaire’s first and only wrestler when Coach started the team in 1980, and in 1981 he was our first state champion. He had wrestled at 171 pounds and wore an impressive size 12 shoes, and as an adult he towered over Coach like my family towered over me. He had a broad smile and was always happy to see his dad and say hello to me. They’d chat about the state’s athletics and Coach would, when asked, offer his thoughts. Like how my family groomed each other to run the Teamsters, Craig was gaining respect in state athletic committees and Coach would sometimes share stories of how he got USA Wrestling started in Louisiana.

St. Pauls never needed supplies and we never lingered; Coach and Craig would shake and chat quickly and wave goodbye, and Coach would take me over to Jesuit High School, home of the Bluejays.

Jesuit was a massive and ornate Catholic school with three tiers of wrestling teams: first, second, and third string. They were so big they held tournaments with only Bluejays competing for first string. There varsity team was away competing in and winning a few national freestyle tournaments, but their second and third string teams were training all summer in one of their gymnasiums, a wrestling-only room that could have swallowed any one of the Region I schools along the River Road. They had two new Bluejay blue mats permanently laid out, and the ceiling rafters were decorated with rows of state championship titles dating back to practically when Louisiana was still a French colony.

Their coach, Coach Sam, was as diminutive as Coach but had been a nationally ranked collegiate athlete and still competed in masters-level judo tournaments. He was half Japanese and a bit younger than Coach, and from a distance they were the same height and had a similar stance, relaxed but centered and able to move in any direction at any moment. I never heard what they chatted about, because I was too busy being slaughtered by second-string Bluejays.

I could hold my own on with their third string, but the second string would throw me around with moves that seemed more like judo than wrestling. I learned to turn face down in midair instead of being pinned, and they punished me for that by slipping half nelsons on me and pushing my face across the mat until it was rubbed raw and as bright red as the pimples I kept hidden under my t-shirt. I learned to fight the half-nelson with pure perseverance, and I quickly learned that whatever brand of fungicide Jesuit used, it didn’t sting mat-burn like whatever Coach’s company bought and gave away.

Ironically, to me at least, because I had been practicing Ku-Kempo with Todd and Lea, I wouldn’t throw someone to their back, which is what wrestlers train to do. When I did that with Todd, he’d pummel me with kicks and fist blows. His sensai gave me free advice, which was to twist in mid throw and bring Todd down face-first, which in a real fight meant you could pummel the sides of an opponents face or bash in their ribs unhindered; by helping me, he was also helping Todd. The down side is that I developed muscle memory and all of my throws only scored a two-point takedown, not getting pins and not setting up back points. Fortunately, I could usually sink a cradle as soon as they hit the mat, so I kept doing what I was doing.

My only intrinsic strength remained a strong crossface and long legs that I’d sprawl all the way back to Clinton high school whenever a Bluejay tried to shoot on me; I’d crossface them and spin behind them and wrap my long arms in a cradle around their neck and one leg. I’d clasp my hands and, like most inexperienced wrestlers, try to control them by muscling my arms together. It sometimes worked against third string wrestlers, but invariably a second string wrestler would break my grip and escape.

On the drive back one day, Coach moved his right hand off the steering wheel and held it up, not like a handshake, but with his thump pressed against the side. The windows were up because we were driving around 55 miles an hour along I-10 to get home, so it was easy to hear him even though he only glanced at me to see if I were looking before looking back at the road and speaking into the windshield.

“A wrestler looses 15% of their strength with their thumb out,” he said.

He moved his thumb out to emphasize the point.

“To have a stronger grip,” he said, glancing at me, “keep your thumb in.”

His thump slammed back against his first finger.

He put his hand back on the steering wheel and watched the road and hummed softly. I practiced clasping my hands with thumbs by the sides and trying to yank my hands apart by thrusting my elbows away from each other. My grip was noticeably stronger the first time I tried it, a rare instance of instant gratification that’s fun to show freshmen just starting out in wrestling or judo; you can try it right now faster than it took to explain it.

On our next trip, I was holding a Bluejay in the cradle as he kicked and kicked, but I was unable to roll him to his back and pin him. I was still squeezing and trying to use muscle I didn’t have. Coach appeared and asked us to hold still.

“Put your left knee here,” he said, pointing to the Bluejay’s lower back.

I did that.

“And plant your foot there,” he said, pointing to a spot on the mat across from my opponent.

“Now push with your foot and pull your hands towards your chest,” he said.

I did, and the Bluejay pivoted on my knee and rolled onto his back; he laughed at how he couldn’t stop it in the way someone laughs on a roller coaster because they feel out of control but safe.

Coach pointed to my clasped hands. “Now move that,” he said, then moved his finger to an empty spot in the air about a foot and a half from my chest, “here.”

I did, and his knee and nose were brought together with no noticeable effort from my arms. His laugh was muffled by his knee pressed against his face. I had defeated my first Bluejay. I kept getting drug across the mat by Bluejays that summer, but whenever I clasped the cradle I usually got them to their backs and often pinned them. They learned to avoid the cradle and I got better at it and at countering throws. By mid summer, our ships were floating higher; when a few wrestlers would come in for summer open gym days, I’d share what I learned and help lift those ships, too.

After Uncle Bob died and I joined the army, I was with Coach on our last drive along I-10 before school began and was crumpling a sheet of newspaper in each hand. The floorboard of Coach’s passenger seat was piled with tightly compressed wads somewhere between the size of a baseball and a golfball. Coach had told me that was a way he and other athletes developed grip strength back in Iowa.

I used the handgrips my dad had bought me at school, but I had grown stronger and though they were the extra strong type I duct taped them together; to stop them from squeaking and alerting teachers what I was doing under my desk, I oiled the springs. Per the instructions that came with the grips, I would alternate holding the grips together as long as I could to develop a “vice like” grip, and squeezing and releasing them as many times as I could to develop a “crushing grip.” Coach said that was fine, and told me a lot of kids when he was in school just used newspapers.

The main way was farm work, he said. Grasping and tossing bails of hay or shoveling pig slop all day is hard work. But whenever they had down time they exercised whatever they could, and Coach said they used to crumble newspapers to get stronger. Had they had grips, he said, they probably would have done both. He handed me his newspaper from that morning, and I had been crumbling every copy I found since.

Monday to Sunday wasn’t too challenging, but the thick Sunday paper led my forearms to tremble by the end. As a treat, I saved the color comics to the end. They would rattle as I held them with shaking hands.

I saw my family in the news at least once a week. Big Daddy was released from prison early because of declining health – diabetes and an ambiguous heart condition – but that was old news’; the focus was on his return and if he was influencing Uncle Doug, who was by then president of the Teamsters, and Uncle Keith, who was a senior labor official that Doug said would take his place. The Partins were a Louisiana legacy, and the articles all mentioned Big Daddy being an all-American hero who risked his life to save Bobby Kennedy’s; on days where I saw that, I crumpled the wads extra tight in Coach’s truck and wrestled a bit harder wherever we stopped.

I was already emancipated and in the army delayed entry program, but I didn’t tell Coach. It pained me; but, as I said, I was unsure if it would affect my eligibility. Asking Coach about the rules would tempt fate and risk what was most important to me. Other than my emancipation and the copied keys, I was transparent with him.

I thought about Vision Quest on those rides. I wanted to ask something but I didn’t know what. I felt new thoughts struggling to manifest as I nudged the balls of newspaper around with my feet. I always wore my wrestling shoes, untied and loosely draped. They were a size 11, snug when laced but comfortable when open.

One day on the way home I was trying to use my big toes to bend the thin rubber soles and pick up one of the tightly balled pages that was mostly about the Partin family. I stopped fumbling with my feet and looked towards the driver’s seat.

“Coach,” I began timidly.

“Yes?” he replied, not taking his eyes off the interstate. He flipped his turn signal and we exited Oneal Lane.

“Why didn’t you try out for the olympics again?” I asked. “I mean, the guy who barely beat you was the greatest. You could have gotten a gold.”

He nodded to show he heard me but kept his gaze on the road and took a deep breath, as if trying to simplify a long story into something more like he would say.

Coach was barely defeated in olympic trial semifinals by Doug Blubaugh, a gold-medal winner in the 1960 Rome olympics who pinned all four opponents in record time, yet he only defeated Coach 4 to 3 in sudden death overtime. Had it been anyone other than Doug Blubaugh, Coach probably would have won trials and earned a gold medal in Rome when he was still a young man.

He had never mentioned his background, but I had overheard other coaches talking about him that summer. I asked him timidly because I assumed, deep down, either without realizing it or without articulating it as a thought in words, that most people didn’t want to be questioned about their personal lives. But that wasn’t Coach. He was as transparent as his truck windshield after we stopped for gas and he used the gas station’s squegy and bucket of cleaner to scrape off all the Louisiana swamp bugs.

After I asked, he peered through the windshield and watched the road and his lips chewed on a possible answer for a while. I suspected no one had asked him that before.

We approached Florida Buelevard and Coach stopped at the red light. He looked at me and said, “Well, by that time I was married.”

He took a hand off the steering wheel and looked at me and shrugged with his palm held up as what he said explained everything and the answer was in plain sight on the palm of his hand. But I didn’t see it. The light turned green and he replaced his hand and turned left onto Florida Buelevard. I waited. We got up to around 45 miles an hour and he shrugged again but kept his gaze forward, and said:

“I had done my best at wrestling, and now I wanted to do my best as a husband.”

He flicked on the turn signal and eased into the right side turning lane across from the Little Saigon.

“And a father,” he said. “Craig was born by then.”

He looked back at the road and said, “I was a PE teacher. They don’t make much money. With a master’s degree I’d earn $1,400 more a year.”

He glanced at me and shrugged as if it were obvious what to do in that situation. He looked back at the road and said:

“So I started taking night classes and earned a master’s in education.”

We stopped at a stop sign and Coach looked at me and smiled and said, “And here we are.”

He turned left and pulled into Belaire’s parking lot and didn’t say anything more about college or how he got to Belaire. He went home to Mrs. K, punctual as always. I jogged over to the Abrams’s house three miles away, clamping the handgrips in one hand until it fatigued and then switching hands along the way.

Season began and we watched Vision Quest and for the first time in Belaire’s history we had a full squad. We didn’t have a second string like Jesuit, and a few guys wrestled heavier classes just to fill the slot for team points, but we had momentum and a sense of espirit de corps rare for a Louisiana sport that wasn’t baseball or football.

I grew a reputation as having a deadly cradle. Teammates said I had a kung-fu grip, and they kept calling both me and my grip tenacious. I was still loosing once or twice a tournament and rarely reached above third place, loosing once in the primary bracket and clawing my way to third-place finals, where I’d either win or loose a second time and finish fourth.

But, like our first full squad, I had momentum carrying me forward and I could see a path unfolding in front of me. Hillary was undefeated again that year, thrashing even Jesuit’s 145 pounder. I didn’t think I could defeat either of them, but I didn’t think I could not, either. I began to see what Doug Blubaugh meant when he told Coach that someone has to win, and it might as well be any one of us.

I used my emancipation paperwork to get my driver’s license using Lea’s van to take the test, but then I made the worse mistake of my life up to that point and broke up with Lea because of some ill-conceived belief that I wanted to be morally superior and avoid anyone who indulged in cigarettes, booze, or sex, probably sparked by Rocky’s cranky old coach Mickey, whose raspy voice said: ‘Dames make legs weak.”

Lea said she was saddened. But, like Coach, she practiced what she preached and after crying a few days said it had been a good ride. More than a year, a lifetime teenagers. “But this too, shall pass,” she said, her version of the Buddha’s last words that all conditioned things are transient. I think she got her version from one of C.S. Lewis’s books on Mrs. Abrams bookshelf.

Lea started college an hour away at Southeastern in Hammond and evolved into something like an older sister of mine who, though promising to visit home every weekend, developed friends her age with similar interests and ended up staying in Hammond most weekends. With her new lifestyle, we probably would have broken up anyway, and if that had happened during wrestling season my ranking would have suffered, and we may not have remained friends in our midlives, or laughed together when I began writing a memoir decades later, both of us happy that things worked out for the best. We had an unshakable faith in what was once truly seen, and we never stopped loving each other.

Her dad understood that I was focused on wrestling and nothing else. While Lea was at Southeastern, he helped me find, buy, and repair a 500cc Honda Ascot motorcycle, one with a shaft drive that wouldn’t need maintenance and got around 55 miles to the gallon so I could drive the 20 or so miles to the downtown training camp for about 25 cents each way.

Life was good, but nothing lasts forever. My motorcycle and I left the Abrams house after their dad developed an aggressive cancer. Just like with Uncle Bob, his deterioration was swift and ugly; the Abrams wanted private time with just family. I heard the hint, and instantly I viewed the Belaire Bengals as my next family, with me in a role that would help grow the family for everyone. I still visited the Abrams and helped move their dad around, just like I had moved Uncle Bob around to clean his backside and to prevent bed sores, but I saw myself as a visitor and friend of the family, the same way I was a guest at Jesuit High School and not on their team. I focused on my goal and the team.

I had to live somewhere, so I moved back with my mom.

She was back with her boyfriend and out of her depression and lived about five miles away in a newer subdivision that was still in Belaire’s district. We rarely saw each other, because I was spending most of my time at either Belaire or downtown, running up and down the state capital steps, or at magic meetings with Ring #178 of the International Brotherhood of Magicians, which met at a synagogue in the wealthy neighborhood of the club president and was almost a half hour away; I’d stay late with some of the older members, mostly empty nesters who had known Big Daddy well and thought it was funny to have me in their club. They even made me “Sargent at Arms,” which is how Chief Justice Earl Warren described my grandfather’s role in Hoffa’s inner circle. It was my job to keep order for people who didn’t know Parlimentary Procedure, which Mr. Samuels, the club president, had asked me to learn before I accepted the role of Sargent at Arms. I wasn’t in the army yet, I told Lea by phone, but I was already a sargent.

I’d let myself into my mom and her boyfriend’s house late at night, and I’d be up and running before dawn. On weekends, she and her boyfriend were in Saint Francisville. They were building their dream home, one that was immune to valuation based on school districts and bussing, and they said they only had a few more months until I graduated and then they’d be free, just like I was. They meant it nicely, but because I had worked so hard to be emancipated when I could have been wresting or performing magic, I felt defensive every time and simply ignored them and trained a bit harder to make up for lost time.

By the Thanksgiving tournament season was in full force. Belaire, remarkably, was consistently winning dual meets and placing in tournaments for the first time in the fledgling team’s few years of history. Wrestlers compete as individuals, but train with a team and their performance on the mat contributes to team scores. Win by a pin was worth more than win by points or a technical fall, and at the end of a tournament the team with the most points won. In a dual meat, a team didn’t fill a spot or a wrestler missed their call to the mat, forfeit points were awarded to the opposing team. The two Bengals who lost wrestle-offs for their weight class and volunteered to wrestle up a class were the only ones of us who ate full Thanksgiving meals, something they bragged about while watching some of us jog around the gym in plastic bags.

I was happy to be a part in that. And I was happy to consistently be called Magik, a name so far removed from my family that I knew my emancipation was a part of me as permanently as anything could be permanent. When not wrestling or practicing, I rode my motorcyle around town in the pleasant fall weather, dodging the thunderstorms that came with hurricane season by dropping into whichever video arcade was nearby. I was, as Lea had suggested, enjoying the ride, and had yet to set my sights on wrestling Hillary Clinton. That was the future, and a wise lovely lady named Princess Lea once told me that no one knows what the future holds in its hand.

Go to the Table of Contents