Wrestling Hillary Clinton: Part I

But then came the killing shot that was to nail me to the cross.

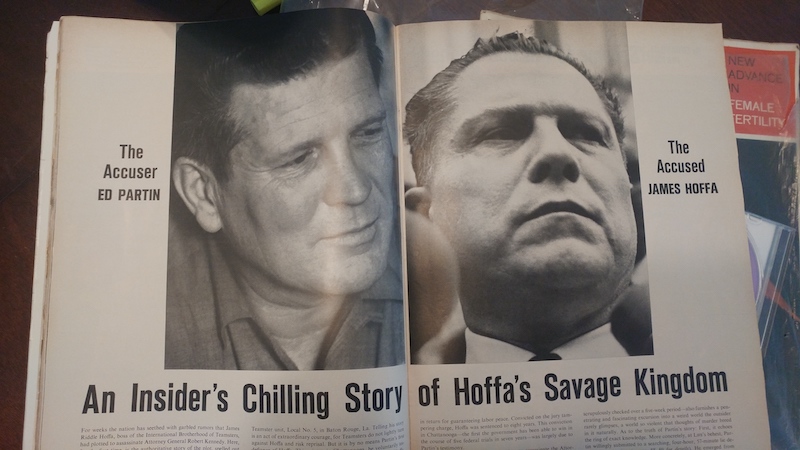

Edward Grady Partin.

And Life magazine once again was Robert Kenedy’s tool. He figured that, at long last, he was going to dust my ass and he wanted to set the public up to see what a great man he was in getting Hoffa.

Life quoted Walter Sheridan, head of the Get-Hoffa Squad, that Partin was virtually the all-American boy even though he had been in jail “because of a minor domestic problem.”

– Jimmy Hoffa in “Hoffa: The Real Story,” 19751

I’m Jason Partin. My father is Edward Grady Partin Junior, and my grandfather was Edward Grady Partin Senior, the Baton Rouge Teamster leader famous for infiltrating Jimmy Hoffa’s inner circle and sending him to prison; according to Chief Justice Earl Warren, the only one of nine supreme court justices to vote against using my grandfather’s testimony in 1966’s Hoffa versus The United States, “…if it were not for [Edward Partin], there would be no conviction here.”

In 1983, seven years after Hoffa vanished from a Detroit parking lot, Ed Partin Senior was portrayed by Brian Dennehy the movie Blood Feud. Robert Blake won an academy award for “channelling Hoffa’s rage” and a daytime soap opera hearthrob portrayed U.S. Attorney General Bobby Kennedy, Hoffa’s nemesis in the Blood Feud, and Brian was an up-and-coming star known for his “rugged good looks,” green-blue eyes, and charming smile.

In 1983, my grandfather was more famous than Brian. Photos of him and my family were plastered across national media in the 1960’s, and he was in the news almost monthly in the 1970’s. Hoffa summarized my grandfather well in his second autobiography, published just before he vanished in 1975: “Edward Grady Partin was a big, rugged guy who could charm a snake off a rock.” That’s the type of actor producers sought, and the young and upcoming actor Brian Dennehy was a good fit. (Coincidentally, Brian’s break-out role followed Blood Feud later that same year, when he co-starred alongside Sylvester Stallone in another film with blood in the name, “Rambo: First Blood.” Brian was the small-town sheriff and Korean war veteran who took no nonsense and led the hunt against Rambo, a Vietnam Special Forces veteran with a huge knife and PTSD.)

People in Baton Rouge called my grandfather Big Daddy. He watched Blood Feud from a big color TV in his plush Texas prison cell, and he thought Brian, though smaller in size, did a fine job portraying him.

Thirty years after Blood Feud, Big Daddy was portrayed by the burly Craig Vincent as “Big Eddie” Partin in Martin Scorsese’s 2019 opus about Hoffa, The Irishman. By then, most people had forgotten what Big Daddy looked and sounded like, and Scorsese said he was making a film for entertainment, not a documentary, so he didn’t need to find actors who matched the original characters. He raised $270 Million and hired a long list of Hollywood’s most famous actors know for gangster films, like Al Pacino, Robert DeNiro, Joe Pesci, and about a dozen others. Craig was chosen to portray Big Daddy because he had worked with Scorsese before, playing a big, brutal, thug alongside Pacino and Pesci in the film Las Vegas mob film Casino. Scorsese changed Big Daddy’s role to a minor one to squeeze it into the whopping 3 hour and 29 minute film, and he replaced his southern drawl to match Craig’s natural northeast Italian accent.

The Irishman sold out theaters until Covid-19 shuttered theaters, then it set global streaming records on Netflix for two years of the pandemic. Millions of people all over the world got a simplified glimpse at Big Daddy’s small part in history. Craig, who had called my surviving family and me to research the role, filled Scorcese’s role precisely. In one scene, Scorcese lowered the camera angle and placed Big Eddie behind all the big-name actors, exaggerating his size and making him loom large over people who didn’t see it that way. I believe that Big Daddy, who died in 1990, would have appreciated how he was portrayed.

There are dozens of Jason Partins on the internet. When I began writing this memoir, I Googled my name for the first time and saw that a few Jason Partins were criminals, a few were people typical in anyone’s town, and one was an aging mixed martial arts competitor who coincidentally looked like a younger version of me. One was – and is – my second cousin, Jason Partin. He’s my grandfather’s nephew and a year younger than I am. That Jason was the football star of the Zachary High School Broncos when we were kids in Louisiana, and he went on to play for Mississippi State University. He currently owns the largest physical therapy treatment center in Baton Rouge, and his smiling face looks down on I-110 traffic from the Lamar Advertising billboards that line I-110 between downtown Baton Rouge and Zachary.

I’m the Jason Partin listed by the United States Patent and Trademark Office as an inventor on several patents as either Jason Partin or Jason Ian Partin. When I began writing this, I was the smiling Jason Partin dressed in a suit on two university’s web sites. I ran a hands-on innovation laboratory called Donald’s Garage, named after Donald Shiley, co-inventor of the world’s most successful heart valve, and I led engineering classes at The University of San Diego’s Shiley-Marcos School of Engineering; and I was an advisor for the University of California at San Diego’s entrepreneurship program in what they called The Basement, a similar concept as Donald’s garage to learn-by-doing and iteration rather than rote memorization.

There were a few other Jason Partins listed as inventors on patents for a range of gadgets, but all of my patents are for medical devices, implants, and technologies that help heal bone fractures and repair soft tissues. Most are focused on small bones and joints, like the facet joints spinal vertebra, ankles and toes, and wrists and fingers. I can’t say for sure, but I believe my interest in healing small broken bones comes from when I broke my left ring finger just below the middle knuckle, two weeks before Big Daddy’s funeral on 16 March 1990. That was the last time I saw my cousin Jason Partin and most of the Partin family.

My finger healed askew, and to this day the two fingers part at the middle knuckle. When I hold my hand up facing you, it looks like Dr. Spock’s split-finger salute when he wished people to live long and prosper in the Star Trek series and films. On x-rays, you can see the fracture line and calcium buildup that would have been stymied by a small screw or simple pin. When I raised investment capital for my first inventions in the early 2000’s, I held up my hand and showed that x-ray and said that my finger would have been a candidate for small-bone healing implants.

I’m a fan of puns and acronyms, so I named the invention Active Compression Technology, or ACT for short. It was simply two implants connected by a NiTinol spring that compressed across the fracture line to facilitate healing, like how clamping a broken board together helps align the ends and lets the glue heal more strongly. NiTinol is a super-elastic and shape-memory metal alloy made of Nickel and Titanium and invented by the Naval Ordinance Laboratory, hence the acronym NiTinol. I smirked every time over three years of fund raising when I told potential investors about NiTinol and said they should “act” now and invest in our company, which was named Lotus Medical after the Hindu flower and had no relation to bone healing at all (some things in my story are random, without intention, because I didn’t know I’d write about it one day). I told investors that I broke my finger wrestling in high school, which is true, and I never told them the funny story about who broke it.

Hillary Clinton broke my finger on 03 March 1990. Back then, Hillary Rodham Clinton was the wife of Arkansas governor Bill Clinton, and he wouldn’t be elected president until 1992. The Hillary Clinton I knew was the three time undefeated Louisiana state wrestling champion at 145 pounds, a fierce beast who would have impressed even Big Daddy. Because he broke it just before Big Daddy’s funeral, those two events are forever linked in my mind.

The joke about that Hillary – though never to his face – was that he was like a boy named Sue in Johny Cash’s song “A Boy Named Sue,” whose dad named him Sue before he ran off. Sue grew up being picked on because of his name, and in the middle the song he meets his dad and beats him in a long, vicious bar brawl; at the end, it turns out his dad named him Sue because he knew he wouldn’t be around, and he wanted his son to “grow up tough” and “grow up mean” without him. But Hillary wasn’t mean. He was terse and focused and intimidating, but he was never mean. He was the toughest 145 pounder in Louisiana and captain of the revered Capital High School Lions, and any jokes about his name were made respectfully and never within hearing distance.

Hillary was born in mid-October of 1971 and began kindergarten at age 5. He turned 6 a month later, and by the end of the 1989-1990 high school wrestling season he was a legal adult about to turn 19. He had been able to vote in elections and buy beer since the 11th grade (Louisiana was the last state in the United States to raise the legal drinking age to 21), and he had been shaving since the 10th grade.

Referees check for clean-shaven faces at ever weigh in, because a few wrestlers shaved a few days before a match to make their chins and arms abrasive like sandpaper or a steel Brillo pad; which, if you’ve ever had a Brillo pad rubbed across your face, hurts more than you’d expect. But Hillary shaved his face smooth each morning before competing, and his stout hairy forearms were so strong that he could get anyone to turn their head with his crossface without needing to cheat. If someone grabbed his leg, he crossfaced the hell out of them and they either let him go or would be so distracted by pain that Hillary could spin behind them and score a takedown. If you wore braces, like I did, his crossface would shred your lips if you didn’t wear a mouthguard.

He was only 5’4″ and hadn’t grown taller in two years. He was like an African American version of the short Canadian comic book character who debuted in October of 1974, Wolverine, but who was only known to comic book fans like my friends and I were. Both Hillary and Wolverine were hairy, muscular, terse, and fierce fighters, so the comparison was obvious to us if not to fans of the Marvel movies staring the 6’2″ Australian Hugh Jackman as a modern Wolverine, but to us the analogy was apt.

Hillary’s burly arms were proportionate, not gangly like a lot of growing teenagers, and his body didn’t waste precious pounds on an otherwise useless extra inch of arms or legs. His thighs bulged with muscles and his lats were wide. To fit into Capital High’s skin-tight maroon wrestling singlet, he had to wear a larger size than his lean stomach needed. His uniform looked like a second skin stretched tautly across his dark chest and thighs, but it hung in loose folds around his stomach.

For three years, Hillary had been captain of the Capital High Lions, a 100% African American school located near the downtown state capital building. Like a lot of downtowns back then, interstates had cut through neighborhoods and created pockets of persistent poverty. The neighborhood around Capital was criss-crossed by the elevated interstates 10 and 110; I-10 stretched from near the east coast of Florida through New Orleans and Baton Rouge and all the way to the Santa Monica pier near Hollywood, but the misnamed I-110 only went from the downtown Mississippi River bridge to a row of petrochemical plants 30 miles north of Baton Rouge.

The dead-end interstate passed the Baton Rouge International Airport, Glen Oaks High (where my mom met my dad in 1971), and the turnoff to Zachary High, where my cousin Jason went to school and my great-uncle, Joe Partin, was football coach and principal. It stopped just before the split that led to either the ramshackle and impoverished Scotlandville High School or Fort Pickens State Park, site of the longest battle of the civil war. (If you continued past Fort Pickens, you drove along miles of pine forests and passed an old paper mille, then reached the quaint plantation borough and retirement community of Saint Francisville, which was only an hour upriver from Baton Rouge by boat). All downtown neighborhoods changed after the interstates cut through neighborhoods and the civil rights acts of the late 1960’s forced segregation; white families with resources moved to neighborhoods with less crime and school districts funded by local taxes, like Zachary and St. Francisville; that cycle of poverty produced the hairy terror I knew as Hillary Clinton.

I lived near Belaire High School, about twenty miles southeast of downtown. Other than wrestlers, no one I knew ventured near Capital High. Their gym wasn’t large enough to host a tournament, but they proudly dubbed their small nook the Lion’s Den and hosted around three or four dual meets every season.

Over a few years, most Baton Rouge wrestlers would have stepped into the Lions Den at least once. I was there twice, once for my first dual meet in 1987, when I weighed 123 pounds and wrestled at 126. Coincidentally, the first match of my life was against Hillary, and I naively shot on him first; his crossface bloodied my nose, and he got behind me and turned me with a half-nelson and pinned me in 22 seconds while I choked on blood. My second time in the Lion’s Den was in 1989, when I was co-captain of Belaire and had to cut weight to make 145 pounds; Hillary pinned me that time with a bear-hug throw in one minute and twenty six seconds.

Like a lot of schools, including Belaire, wrestlers shared a gym with the basketball team. Wrestling mats are split into three hefty segments that take a small team to unroll. Every day, small schools with shared gyms spent the beginning of practice unrolling the mats, taping the seams, and mopping them with fungicide; and the end of practice, teams cleaned and re-rolled the mats to clear the floor for the next day’s gym class. Capital’s mat stood out because their wrestling mat was a faded and duct-taped purple and gold mat donated after LSU’s team disbanded in 1979. Capital, like Belaire, began their program soon after LSU disbanded, along with around 100 teams nationally, after the Title IX law required equal numbers of males and females in collegiate sports; overnight, Baton Rouge had a surplus of expensive wrestling equipment and dedicated coaches. Smaller schools like ours were the lucky recipients.

The first thing you saw as you approached the Lion’s Den was a hand-painted sign above the doorway, large gold letters against a black scroll that said welcome to the Lion’s Den. Inside, tufts of asbestos dangled from their rafters. The walls were painted maroon to match their singlets and warm-up hoodies, and students had painted over the maroon with gold and green murals of lions and kings with crowns. The maroon paint was so faded it was a close approximation of LSU’s deep purple mats, and the residual gold lettering somewhat matched Capital’s murals.

Like most wrestlers I knew, I thought the Lions were paying tribute to the colors of New Orlean’s Zulu parade, which was known for its African heritage. From their floats, the Krewe of Zulu tossed bright green, gold, and purple bead necklaces with a king’s crowns hanging from the center, and they handed out gold doubloons molded with raised images of majestic lions that matched what I saw on Capital’s walls. Years later I realized the murals were the Lion of Judah, a symbol of strength, courage, and sovereignty, and that the colors were from the flag of Ethiopia and only matched Mardi Gras colors because of overlapping Old Testament heritages.

I recall thinking their den represented Daniel and the Lion’s Den from the Book of Daniel. That made sense, because wrestlers, like Daniel, fasted. He did it for faith, we did it to make weight. A few of my teammates and I would fast 24 hours, sometimes up to two days. For dual meets at Capital, we, like Daniel, finished fasting and stepped into the den to face a pack of lions.

Hillary led the pack. He would be at the head of the Lions lineup as they trotted onto the mat to warm up. His skin was so dark that his singlet appeared a darker shade of maroon than the other Lions, and when he wore his hoodie his face disappeared in its shadow. The rest of his team followed in a row beginning with their 103 pounder and ending with their 275 pound heavyweight, like a line of purple hooded Russian Matryoska dolls but with their 145 pounder placed in front.

The Lions trotted onto the old LSU mat and jogged in a circle while stomping their feet in unison and remaining eerily silent. Every team had its own warm-up ritual, but what stood out about Capital – besides the obvious racial difference – was the contrast of their vocal silence against the musical echo of their feet echoing in the gym. Their foot pattern mimicked a funky rhythm in the style of popular performers from the 70’s and 80’s, like James Brown or George Clinton, and as they circled they stomped the mat harder with their left foot on every forth step, like the 1 of a 4 step beat: ONE two three four, ONE two three four… The echos reverberated in the small enclosed room and we could feel the beat in our chests while we waited our turn to warm up.

The Lion’s spectators filled their relatively small set of worn wooden bleachers and stomped their feet on the one with Hillary and his team. They rented cheap houses that had once been built for the middle class, or small apartments in the eight unit rectangular brick buildings that dominated their neighborhood after I-110 was built, but they radiated more pride than any suburb school I knew. Every time spectators stomped on the one the stands would shake and rattle, loose screws would squeak, and flakes of paint would fall off the bleachers. No one seemed to notice the derelict stands other than visiting teams, who were more used to modern gyms without asbestos and quiet spectators.

When the Lions finally stopped circling and sprawled into a tight circle, they landed with their faces close together, and they did it on a silent cue that no one watching could decipher. The spectators would calm down and give the team a moment of silence, and Hillary spoke so softly that I never heard what he told his team as they prepared for battle. For about two minutes, the den became a church; there’d be no stomping or squeaks from the stands, just an occasional cough or someone clearing their throat.

When it came time to compete, Hillary would stop warming up and take off his hoodie and don his light brown hockey mask, like the one worn by Jason in the 1980’s Friday the 13th slasher films. It wasn’t an actual hockey mask, it was an wrestling mask for kids who competed with a broken nose. A hockey mask is rigid and covered in holes, but a wrestling mask is padded to be soft on the outside and has only two holes for eyes and one for the mouth, but it looked so much like a hockey mask that we all called it one.

The analogy with Jason the slasher was apt because, like Hillary, he also never spoke and showed no mercy. It was so hard to miss that I assume he began wearing it in 1989, when I first saw him step on the mat with it and he pinned me a minute and twenty six seconds later. He was one of only three wrestlers in the Louisiana to wear one that season. His nose wasn’t broken like theirs was, but the mask protected him from crossfaces and, I suspect, added to his reputation as a silent killer on the mat. No one made the joke about my name being Jason, not Hillary’s, because practically every person in Baton Rouge called me by my nickname, Magik. But I thought about the irony every time Hillary and I faced off.

I had tried to wear a mask after another wrestler bloodied my nose early in 1989. I could breathe more easily in it than with the silicone mouthguard that protected my lips from being sliced aparrt, but I couldn’t see clearly through the two eye holes so I abandoned it. Instead, I began to strengthen my neck muscles using Belaire’s football team’s weight room, focusing on resisting Hillary and other strong wrestlers. It was a double-edged sword, because a stronger neck didn’t reduce the pain; the more you resisted, the greater the pain and the longer it lasted. But it was worth it, and by January of 1990 I was holding off all three rounds and loosing to Hillary by a few points instead of being pinned. The city tournament would be our 8th match, and though I didn’t know it yet it would also be our last.

Like a lot of us, Hillary had to sweat off a few pounds before each match. He would drape a black plastic law bags over his torso and run up and down the 34 flights of steps inside Louisiana’s state capital building. It was, and is, the tallest building in Baton Rouge and an icon of our city. It was tallest in America when I was a kid, an architectural gem built during the depression by Louisiana’s Kingfish, Governor Huey Long, when labor and materials were cheap. It’s the second tallest flight of stairs you could run up in all of Louisiana. The first is inside of LSU’s Tiger Stadium, which we all knew you could see from atop the state capital.

Practically every kid in Baton Rouge toured the capital in middle school, where we’d learn about the Kingfish and how he built the new capital. It was on the original grounds of Louisiana State University, called “The old war school” because it trained southern officers to fight in the civil war. A few teachers called that war “The war of northern aggression,” some as a sarcastic joke and others as a lingering belief made stronger by the pockmarks on downtown buildings and tombstones from northern bullets, and from cannon balls on display that had been launched from iron clad warships coming up the Mississippi River and bombarding towns and plantations around Saint Francisville, which was named after the patron saint for kindness by slave owners who didn’t see the irony.

When we toured Fort Pickens, we’d see stumps of trees on display with two cannonballs embeded on opposite sides, one from the north and one from the south, and we’d watch reenactments of the battle that lasted almost a year and a half but simplified into ten minute shows led by men whose great-grandfathers had fought in what some of them also said was the war of northern aggression. The state capital museum didn’t have those reenactments, but it had plenty of cannons and cannonballs and bullets, and it showcased how the officers of that long battle learned to be leaders, emphasizing how bravely they fought to preserve their way of life. A few trinkets with the rebel flag were for sale that said: “Heritage, not hate.”

Like most kids, we didn’t think much about what we saw other than having a day away from classrooms to enjoy being outdoors in springtime. I don’t know what Capital high kids saw. Most schools toured in Mardi Gras season, which lasted an entire month each spring and shifted dates depending on when Easter fell. Everyone wanted to get outside when the typically muggy southern Louisiana weather was still mild. The landscaped state capital grounds would be ablaze with red azaleas, and the air would be filled with the sweet sent of jasmines, and we’d walk past those fragrant gardens, poke fingers in bullet holes, peek at the old war school, and tromp up the 49 outside steps, one step for each state in the union when the capital was built. At the top, at least one kid would turn around and toss his hands up like Sylvester Stallone did on the steps of Philadelphia’s capital in the first Rocky film.

Once inside the tower, we’d split into groups of about eight kids and squueze into the ancient elevator and ride to the top. Those of us who waited stood by the mural of then U.S. Senator Huey Long being shot at point-blank range in front of the elevator, and of Long’s bodyguards shooting the alleged gunman. His corpse had almost 60 bullet holes, and some people believe Long was shot by a bodyguard in the chaos, Long died in 1935 at the beginning of his presidential bid against incumbent President Franklin D. Roosevelt. We were told he was the first senator assassinated; the second was Bobby Kennedy, who was shot and killed in 1968.

Coincidentally, Bobby was also at the beginning of his presidential bid. His older brother, President John F. Kennedy, was shot and killed on November 1963 when Bobby was the U.S. Attorney General hunting down Hoffa like Brian Dennehy hunted down Rambo. Both Long and JFK’s alleged assassins never stood trial because both were shot and killed, so we’ll never know the truth about them, but Bobby’s redundantly named assasin, Sirhan Sirhan, stood trial and is still in prison as I write this four decades later.

Roosevelt incorporated many of Long’s ideas into policies trying to nudge America out of The Great Depression. But, like with most economic downturns, it would take a war to create enough manufacturing jobs and technologies to resuscitate the economy, and it was WWII that turned America into the technology powerhouse we know today.

Teachers would tell us historical tidbits like that while we waited for the elevator, and I went on that tour with three different schools and teachers so it stuck in my mind more than the history lessons I mostly ignored in class, despite not focusing on the teachers. Like most kids, I was more interested in the bullet holes. We couldn’t finger them because a plexiglass sheet protected them, but we’d stand beside them and the mural of Long’s last moments while we stood, bored, and waited for up to half an hour for our turn in the elevator. Had I known then what I know now, I would have taken the stairs.

From atop the capital we could see all of the world. We stood in a crow’s nest with six metal telescopes bolted to the edge that only cost a dime to use and were next to a sign pleading for people to not toss pennies over the edge. Even without them we could see for dozens of miles along the meandering Mighty Mississippi River and across the flat forests between us and New Orleans. About three miles upriver was Death Valley, LSU’s Tiger stadium, the fifth largest college stadium in the world and probably the most unique; the outside looks like apartment buildings because it is.

Huey Long loved the old war school and he drained the swamps near downtown to build the modern LSU campus and model it after a quaint Italian town, but with massive sprawling stately oak trees draped in grey Spanish moss. He couldn’t get state legislators to fund a new football stadium, but he convinced them to fund dorms for athletes, and the dorms he built happened to be in an oval shape and looked like a Roman colosseum with a football field and 80,000 stadium seats inexplicably in the center. One of Long’s brothers owned the construction company that built the dorms, and no one else noticed the inside until it was completed.

Baton Rouge revolves around LSU football. On game day, Death Valley becomes one of the largest cities in Loiusiana. Almost 90,000 fans concentrate on the bleachers, and up to thirty thousand tailgaters are outside around BBQ pits roasting whatever the opposing team’s mascot is, like pigs for the Arkansas Razorbacks and alligators for the Florida ‘Gators. People said you could see Death Valley from space, a glob of purple and gold specs concentrated in an area the size of a few football fields. It’s impossible to miss from atop the capital building, which, from our perspective, was as high as we could imagine being. Huey Long’s brother, the equally quirky Governor “Uncle Earl” Long, a man committed to an insane asylum while in office and therefore could pardon himself, was so enamored by our capital that when visited Manhattan he flamboyantly told reporters about how tall our capital was as if the towering skyskrapers behind him didn’t exist; to him, the probably didn’t.

Tiger Stadium is the heart of Baton Rouge. Like in the Lion’s Den, fans often jumped up and down in Death Valley’s bleachers, syncing with the Tiger marching band’s beat. On 08 October 1988, three days after my 15th birthday and when I was nearby training for wrestling, LSU fans in a sold-out game celebrated a winning touchdown pass against Auburn with so much enthusiasm and for so long that the waves superposed and created a 3.8 magnitude earthquake measured on the Richter scale. It was measured by a LSU physics laboratory, and that game is still listed in The Guinness Book of World Records as the only human-generated earthquake ever recorded. For all of us, seeing Tiger Stadium from atop the capital was a highlight of our youth. Collectively, we felt the pride for Death Valley that the Capital High fans felt for their Lion’s Den.

Twenty miles downriver from the capital were billowing smokestacks from a row of petrochemical plants at the end of I-110 deemed Chemical Alley. Companies like Exxon, Dow, DuPont, CoPolymer, and many others processed crude oil from our offshore oil rigs and shipped gas and plastics from Baton Rouge using Teamster 18 wheelers that would haul the goods along I-110 and connect with the raised I-10 that created the ceiling of Capital’s neighborhood.

Big Daddy was instrumental in the deal to bring big companies to Baton Rouge. I-110 bypassed the railroad, airport, and river ports of Baton Rouge and Plaquemine, and Big Daddy’s tactics ensured companies only used union truckers, not rail lines, planes, or barges. In one story I recall from Uncle Doug, Big Daddy’s little brother and his successor as president of Local #5 beginning in 1981, one of the paper mills near Fort Pickens wouldn’t hire union truckers, “because we got a lot of niggers who work for half the price.” Big Daddy, Doug, and a handfull of Local #5 Teamsters responded by falling a few tall pine trees across the road leading to the mill; the non-union truckers got out to move the trees and were never seen again. There are a lot of alligators, raccoons, opossums, foxes, and fire ants in the bayous and rivers there, and even if police had looked it’s unlikely they would have found any bodies.

The next day, Big Daddy returned and said he heard the mill could use some truckers, and Local #5 was given the contract. Soon after, he began using more traditional methods of negotiating deals with petrochemical companies, and he steered the state legislature to build the otherwise irrationally placed I-110. Those stories weren’t shared on field trips, but they were part of what I overheard growing up in the Partin family and the Teamsters, whose lifeblood was a fleet of trucks and whose arteries were interstate highways, flowed in and out of our homes and were happy to have work no matter how it happened.

I-10 crossed the almost mile-wide Mississippi river using The Baton Rouge bridge, a steel truss arch rumored to be lower than federal waterway standards as an intentional act by Governor Long to prevent larger barges from passing upriver, forcing them to stop in the port of Baton Rouge. It was more than petrochemical products crossing the bridge; I-10 stretched from Florida through the ports of New Orleans and Baton Rouge and all the way to the Santa Monica pier in Los Angeles, connecting international ports like Miami and New Orleans, the second largest in America after new York, to the rest of the country, receiving goods and shipping commerce.

I was told that every thing on every shelf in America had spent time in the back of a Teamster’s truck. Teachers told me my grandfather had run the Teamsters like Huey Long had the state, and they did it with the same smile as when they talked about how Tiger Stadium was built. The Teamsters always supported teachers union strikes, threatening to shut down Louisiana’s economy if state legislators didn’t do what Big Daddy asked.

Teamsters drove the economy using I-10, and it crossed the almost half-mile wide Mighty Mississippi River in Baton Rouge. The bridge was a few football fields away from the state capital building, and across the bridge were a few cement factories around the small port of Plaquemine and endless miles of sugar cane fields. From our perch atop the capital, barges and ships floating along the world’s fourth larges river, the Mighty Mississippi, looked like bathtub toys, and the 18 wheelers rumbling across the bridge were like Hot Wheels on a plastic racetrack.

According to rumors, Big Daddy had finagled building the newer buildings and the addition to Tiger Stadium that added a few more thousand seats. That seemed to explain his entourage, which included a handful of burly Tigers from the 1954 national champion team and their Heisman Trophy winner, hometown hero Billy Cannon, a man more famous in Baton Rouge than any president of The United States had ever been. If Billy and the 1954 national champion Tigers bowed to Big Daddy, that gives you an impression of how people in Baton Rouge viewed my grandfather and his army of Teamsters.

Back in Hoffa’s day, the threat of a national Teamsters strike slamming the American economy to a halt scared senator and future president John F. Kennedy, chairman of the U.S. Labor Commission, so badly that he began focusing on ousting Jimmy Hoffa from power. After Kennedy became president, he appointed his little brother, Bobby Kennedy, a fresh Harvard law school graduate, to be the U.S. Attorney General with only one goal: get Hoffa.

The moniker Blood Feud was coined by media because of the constant, fierce, public battles between Bobby and Hoffa. They were known to push and shove each other in front of reporters, and Hoffa called Bobby “Booby” and “That snot-nosed little brat” in front of reporters weekly. Legendary FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover reported to Bobby, and Bobby had him hire Walter Sheridan to lead 500 FBI agents as the Get Hoffa Task Force, a spectacle media dubbed as the most expensive, fruitless pursuit of one man in any government’s history. Hoover himself oversaw parts of the pursuit and was forced to update Bobby, a man he publicly disliked, almost daily, and Hoover threw every ounce of FBI technology at getting Hoffa.

To my teachers, my grandfather and Hoffa were versions of the Kingfish they knew and remembered, and they were always excited to have a Partin along on field trips and would ask me about my grandfather. My response always got a chuckle: I pleaded the fifth amendment. For a kid who didn’t pay attention in class, I knew a lot about the constitution’s right to remain silent.

Sometimes, while waiting for the elevator beside Huey Long’s bullet holes to open, I’d see high school wrestlers from the downtown training camp bypassing the elevator and stepping into the stairwell. They’d be dressed in different colored sweats or draped in the big black plastic trash bags we used to collect pine needles in the fall, sweating and yet still running up and down the stairwell steps as if Rocky could have gone inside his state capital building. Unlike every school I knew, they didn’t seem to be part of a team and they were of all races imaginable in our small world: white, black, Creole, and a few Asian. In high school, I’d learn that they wore multi-colored hoodies because they were part of the downtown all-city wrestling camp.

The camp was a nonprofit formed by former LSU wrestlers, and all they could afford was a dilapidated and asbestos-lined former auto repair garage that they stuffed with faded and duct-taped purple and gold wrestling mats. Title IX was fiercely contested, especially by athletes who lost their scholarships, but the disgruntled LSU wrestlers who had relocated from midwestern towns loved the sport so much that they banded together and opened a training camp in the only part of town they could afford.

The former Tigers would show up after their day jobs and train with any kids who made it to camp after school; or, during springtime and leading up to the city tournament, any time of day they could get a pass. From camp, if you walked towards the capital you’d walk the route of northern soldiers during the civil war, and you’d pass churches and tombstones riddled with their bullets; that’s the route wrestlers would take to run the state capital steps.

I followed the same route when I became one of those high school wrestlers. Invariably, Hillary would already be at the capital. It’s not cold in Louisiana, snowing only once every decade or so, but we’d all be dressed in layers as if running in Antartica. A few, like Hillary, would add a layer of plastic. The heat and trapped sweat saps your strength, but it’s a balancing game; extra sweat means fewer laps up and down the steps. Only the wrestler knows their balance between an extra layer in one hand versus an extra hour in the other.

Once, I saw Hillary running up and down the steps. His face was hidden in the shadows of his hoodie, and he was wearing plastic bags and spitting into an old 16 ounce Gatorade bottle. He was chewing gum salivate more, shaving off a persistent pound by not swallowing his spit. That probably saved him a few laps up the steps or gave him an extra half hour of sleep.

USA Wrestling rules changed in the mid-1980’s and allowed two extra pounds for each weight class after January 1st of each season. The idea was to account for growth spurts after the Christmas break, and January 1st was close to the midpoint of a four month wrestling season. USA Wrestling didn’t want kids starving themselves to stay in the same weight class. Though we competed in what was called the 145 pound class, by March of 1990 every time Hillary Clinton stepped on the mat he was a 147 pound hairy terror.

I never learned his average weight, but I assume he was around 154 pounds most days. At tournament check-ins after Christmas, he’d toss his gum into a trash can, strip naked, wipe his body dry, and fully exhale before stepping on the scales. The needle would barely move up and down before settling on exactly 147.0 pounds. There wasn’t a gram of anything wasted on Hillary. Even his hair was cut as tightly as an army buzzcut, an uncharacteristic style back then.

I was the opposite. I was born on 05 October 1972, which meant I began kindergarten in 1977 at four years old, the youngest kid in class. Had I been born a few days later, I would have been to young to start kindergarten and I would have been pushed back a year and began at five years old instead of four; I would have began my senior year at 17 instead of 16. Instead, I began my senior year as a mid-pubescent kid with disproportionately long arms, wide hands, long knobby fingers, and scuba fins for feet. My toes were bulbous monstrosities best kept hidden inside of tightly fitting wrestling shoes that, on my feet, looked like two torpedos strapped to the bottom of my legs.

My blue Belaire singlet was pulled taunt by my long torso. I had negligible underarm hair, and my pale face and shoulders were dotted with bright red pimples that stood out against the blue singlet. I had auburn hair that seemed to turn red with the increased sunlight of spring, and my headgear was off-white.

I had never shaved and didn’t need to. Unlike Hillary’s leg and forearm hair, which was thick and curly like Brillo scouring pads used to clean cast iron skillets, the hair on my arms and legs was soft like the fur on a puppy. I never stripped naked to weigh in because I was embarrassed to have only a few scragly black hairs hidden by my underwear. The hair on my head was close-cropped on the sides, almost like in the army, but it was a bit longer in the back, like a mullet style awkwardly popular in the 80’s.

My mullet was less to be fashionable and more to hide a few scars on the back of my head, including an 8-inch long, finger-width thick scar and shaped like a big backwards letter C that I had hidden with hairstyles of the 70’s and 80’s ever since I was five years old. My left hand, which wasn’t broken yet, also had a C-shaped scar along the first finger from tripping with a machete in my hand when I was ten years old and helping him cut down male marijuana plants on his farm in Arkansas, a trick he taught me to make seedless and therefore more valuable buds called sinsemilla, from the Spanish word for without, sans, and the word for seed, semilla. The front and back of both hands were sprinkled with pinpoint scars from handling barbed wire on the farm.

My legs were lanky, like with most growing kids, but they were strong from hiking the Ozark mountains in middle school, scurrying up ravines with a backpack of horse and chicken manure to fertilize marijuana patches scattered throughout the dense forest; to avoid detection, my dad cleared many small patches instead of a few large ones, and hid them in the hardest to find valleys.

In high school, after my dad went to prison in 1986, I augmented my leg strength with runs in capital steps and laps up and down the Belaire football bleachers. On a few lucky occasions, I’d ride with a teammate and we’d sneak into Death Valley when no one was there, and we’d run up those bleachers a few times, jumping up and down at the top as if the Tiger Marching Band were playing just for us.

My cross-face was strong. Not because I had upper body strength, but because when I pushed my fist across someone’s face my bulbous thumb knuckle caught and opponents nose and hurt more than a Brillo pad ever could. I was rarely taken down by a shot because my crossface would deflect their face and halt their momentum. But my Achilles Heel, the weakness I couldn’t seem to overcome, was my lack of upper body strength. I was vulnerable to throws and bear hugs by stronger opponents like Hillary, and no amount of training would help me catch up with him.

The difference between Hillary and me is obvious in hindsight. Coincidentally, in the mid 1980’s a research scientist in Canada noticed that professional hockey players were statistically likely to be born in spring. At first it seemed like astrology, but then researches realilzed that Canadian laws required being five years old by January 1st to begin practice; kids born the first few months of the year had an entire year advantage over kids born in the final few months. Every year after, the kids who started sooner outperformed the ones who didn’t, and they placed higher and were therefore promoted faster and received better coaching, similar to how Hillary began kindergarten as the oldest kid in class and I began as the youngest.

That research study was practically unknown until brought to the world’s attention in 2008 by a book: “Outliers, the Story of Success.” It was written by Malcom Gladwell, a Canadian by birth who became a journalist for The Washington Post, writer for the New Yorker Magazine, author of several bestselling books, and popular TED speaker. He combined other research studies to paint a bigger picture in Outliers, and he pointed out that America didn’t have the sports laws as Canada, but the age cutoff for kindergarten creates a similar academic disparity: older kids in kindergarten begin with a 17% advantage on aptitude tests. Like how older hockey re placed in more competitive groups and therefore grow stronger in a self-fulfilling prophesy, many older American students are grouped academically and their initial advantages grow over time; the gap between those who have and those who don’t have grows based not astrology dictating our lives, as Gladwell wrote, but on the initial advantages between kids five years versus four years old, which is 20% more time on an exponential scale of mental and physical growth.

Gladwell coined this phenomenon “The Mathew Effect” after the New Testament’s book of Matthew, where Matthew wrote something like:

Whoever has, will be given more, and they will have an abundance; whoever does not have, even that will be taken from them.

Most of Gladwell’s books focused on topics like David and Goliath, a book about how little companies outmaneuver big ones, and Blink, those brief moments of intuition that outperform teams of experts. In Outliers, Gladwell pointed to the unseen trends that shape success, like which month you were born, but though dozens of interviews and case studies and research reports he showed how constant, persistent determination and practice seems to help anyone succeed. He interviewed people like Bill Gates and cited famous bands like The Beatles, and pointed to the 10,000 hour phenomenon that implies 10,000 hours of effort is necessary to overcome obstacles. Most outliers, by Gladwell’s definition, are lucky; others create their abundance.

I knew none of that in 1989. But I knew that if I had anything in abundance, it was what my teammates called tenacity. Some people called it persistence, grit, or determination; my mom called it stubbornness, a trait she said I inherited from my dad. I had lost all 13 matches of my brief, three week stent of wrestling in the 10th grade, the year after my dad went to prison and I was floundering to adapt to school again. I began my junior year not much better, but by the end of season I was ahead 75 wins to 36 losses.

That’s twice the number of matches most kids have because of how tournaments run. You must loose twice to be eliminated, and the highest seeded wrestlers begin by competing against the lowest seeds to reduce the likelihood of an upset and increase the chances of the two best wrestlers meeting in finals and having more exciting matches for spectators. In a way, that’s a version of the Matthew Effect, because the better you are the easier your first few matches are at each tournament and the higher your ranking becomes.

For those of us who populated the losers bracket, we began in the top bracket against the best but would start over anew in the bottom bracket, where we’d claw our way towards third-place finals. A year of fighting in the loser’s bracket was like putting in 10,000 hours of work.

I began my senior year with 124 matches behind me. I was only 16 years old, but, by a quirk in Louisiana law, I was a legal adult like Hillary, though I couldn’t vote buy beer like he could.

I grew up in and out of the Louisiana foster system. My dad, Edward Grady Partin Junior, began to be arrested for selling drugs when he was a high school student in the early 1970’s. He went to federal prison in 1986 as part of President Reagan’s war on drugs, coincidentally the same year Big Daddy was released early due to declining health (news reports said he had diabetes and a heart condition that wasn’t described further). My mom suffered bouts of depression, and at the end of my junior year I lived with her aunt and uncle, my great-Uncle Bob and great-Auntie Lo.

They were French Canadians who settled in Baton Rouge (which means “red stick” in French, Uncle Bob taught me), and they had also looked after my mom when she moved to Louisiana from Canada as a five year old girl in 1961. A few years later, Granny, Auntie Lo’s sister, finally could afford a small $36,000 home a few miles from the Baton Rouge airport and in the Glen Oaks school district. When my mom was 16 she met my dad at Glen Oaks High, and I was born ten months later, on 05 October 1972.

In 1973 Judge Pugh removed me from my parents’s custody and place me in foster care, and I began alternating homes every few years. I bounced back and forth between my dad and mom in the 1980’s, and by 1989 it was Uncle Bob and Auntie Lo’s turn again. Soon after, and though only 64, Uncle Bob developed spinal cancer and it spread quickly.

Uncle Bop passed away the August between my junior and senior year. Auntie Lo was a lush and I couldn’t stay with her without becoming a caregiver, and I couldn’t get a driver’s license to attend summer wrestling camp without parental consent, so as Uncle Bob lay dying I petitioned the Louisiana court system for emancipation. I knew that an emancipated kid couldn’t suddenly vote or buy beer, but they could do things without parental approval, like get a driver’s license and sign a lease or a contract.

My emancipation petition was overseen by the coincidentally named Judge Robert “Bob” Downing, the current family court judge in the same courthouse where Judge Pugh removed me from my family 16 years earlier, a downtown building and seat of East Baton Rouge Parsih 19th Judicial District. Louisiana is the only state in America with parishes instead of counties, a quirk left over from Catholic influence when the French colonized Louisiana (which was named after France’s King Louis and Queen Anna). To this day, Louisiana is the only state in the United States with a legal system based on the European Napoleonic code. Tulane law school in New Orleans is known to attract people from all over America because, as Uncle Bob quipped, Louisiana is the best country in America to study international law.

The Napoleonic system gives judges more leeway than in other states, and Judge Bob (as I called him) was impressed that I knew that. In our first meeting, I told him that Uncle Bob taught me a lot of things about languages and international law. He was manager of Montreal’s Bulk Stevadoring in New Orleans, and he traveled abroad to negotiate loading and unloading international cargo freighters. He wasn’t overtly religious, but he was raised Roman Catholic and spoke Latin, the language of old bibles, fluently. It was because of him that I don’t quote the bible; each one is a translation prone to error, so I learned to say things like “Mathew said something like…”

The only example Uncle Bob gave of errors in translation was, ironically, Mathew 13:12, the one Malcom Gladwell quoted. Some versions say you’ll have more, and some say you’ll have an abundance. The difference is great. An abundance, from the Latin word abundancia, means “enough to share,” whereas some people interpret it as more and stop there.

Judge Bob was like Uncle Bob in that he respected my hustle in getting magic shows. I did that around the Sherwood Forest neighborhood when I lived with Uncle Bob, and I did it around Belaire to pay for my emancipation petition. I earned the $140 fee by going door to door and performing an effect and handing out business cards with my stage name, “Magic Ian,” a play on my middle name that looked like “magician” on my card, and by handing out copies of a news article of me performing a public show at a local synagogue. I brought a copy of that article, a full-color photo of me wearing a gold magic top hat with a rabbit around my neck, to show Judge Bob that I volunteered in my community and was therefore, in my logic, already doing things a respectable adult should do. I was not like my family.

Like most people in town, Judge Bob knew the Partin family well. For a city of only around 150,000 people and only a dozen Partins in the phone book, there was a lot of media focus on us. After Big Daddy went to prison in 1980, my uncles, great-Uncle Doug Partin (my grandfather’s other little brother), and Uncle Keith Partin (my dad’s little brother), stepped in to fill his shoes. Louisiana depended on Teamsters so much for the economy that they took over as the Partins already discussed weekly in every state newspaper, and though Doug and Keith were no where nearly as notorious as my grandfather, his name followed theirs in almost every articles. Joe and Jason were in the news, too, but that was mostly the sports section. I hadn’t placed in a tournament yet, so I was never in the news other than a few articles about magic and the local magic club, The International Brotherhood of Magicians Ring #178, The Pike Burden Honorary Ring, where I was the youngest member and the Sargent at Arms.

Because of Louisiana’s system, Judge Bob could waive the waiting period to reach my dad and get his approval for my emancipation. I said I hadn’t seen my dad since he was released from prison a year before, and I brought in a few stamped postcards to prove it. Every one was in black ink and in his meticulous, perfectly aligned script handwriting; if you glanced at them, you’d think they were done by a perfectionist, especially if you read the first line where he began by telling me how much he loved me. But when you read them, they quickly evolved into rants about what an asshole Reagan was.

The cards were always nature scenes, moose in front of mountain ranges at the border of Washington State and Canada, a mountain lion from Big Bend National Park at the border of Texas and Mexico, and an elk in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, where my dad said he could live out his days as a mountain man if that asshole Reagan hadn’t taken his land and money; it was unconstitutional! he penned in his immaculate handwriting. Fuck him! it said. One card from Arkansas showed fog over the rolling hills of the Ozark Mountains, and it had a cryptic message saying he’d get his high school diploma and go to law school and show the world how the war on drugs was unconstitutional bullshit, driven by the fundamental Christian whackos who put that asshole Reagan in power.

I told Judge Bob that schizophrenia ran in my family, and he didn’t doubt that. In a year’s worth of cards, not one implied he’d ever return to Louisiana, and there was never a consistent address or phone number to reach him. He used those postcards to justify waiving the waiting period for my dad’s signature, part of the leeway granted him by the Napoleonic system.

Judge Bob called a meeting with my mom, who was in another bout of depression and didn’t contest the petition. Considering how sluggishly things creep along in a muggy Baton Rouge summer, Judge Bob allowed my emancipation in only a month. By comparison, in 1976 Judge Lottinger regranted my mom custody of me, but I languished in the foster system for another three years before moving in with her. Because of experiences like that, I was pleasantly surprised when a month after I began my petition Judge Bob stamped my petition with the raised seal of Louisiana, a mother pelican nesting baby pelicans, and sprawled his name across it and scribbled the date, 28 August 1989.

The Baton Rouge Advocate used my entire name in their weekly court summary, perhaps so there would be no confusion with my cousin. It said:

Jason Ian Partin was emancipated by Judge Robert Downing of the East Baton Rouge Parish 19th Judicial District, and has all of the privileges entitled by emancipation.

That blurb from the Advocate is archived online decades later at TheAdvocate.com, and my match against Hillary is also now archived the Louisiana State High School Athletic Association, LHAA.org. Like most of my family history, this much of my story is public knowledge and once you know which Jason Partin or Edward Partin you’re reading about. The story tells itself if you filter out the rest. What follows is my perception as a 16 year old legal adult who knew enough about my family to leave it however I could.

Go to the Table of Contents

- From “Hoffa: The Real Story,” his second autobiography, published a few months before he vanished in 1975 ↩︎