Wendy Anne Rothdram

1955-1972

In the 1950’s, my grandmother was a young woman, living a comfortable life in Richmond Hill Canada, a neighborhood of Toronto. She was petite, barely 5 feet 1 inches tall. Or, as Canadians say, she was a’boot 1.5 meters tall, ‘eh. Her wrists were so thin that her watch would barely fit around the wrist of an average eight year old girl, but her hands were big enough to hold a cocktail glass in one hand and a cigarette in the other. She enjoyed life.

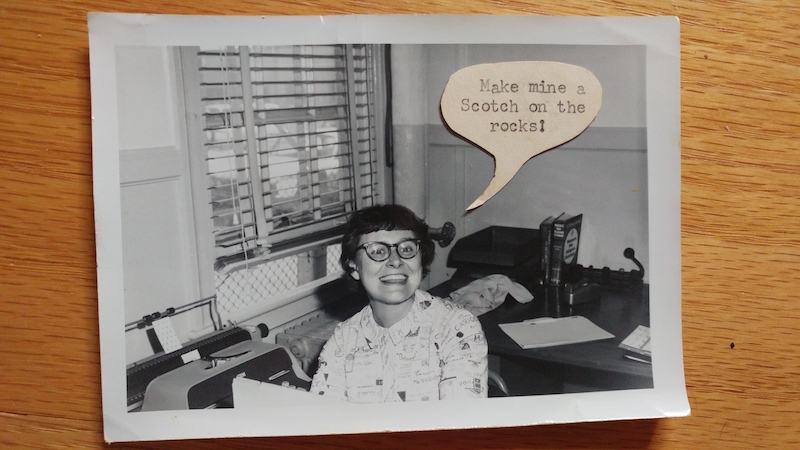

“Make mine a Scotch on the rocks, ‘eh!” she’d say at parties after work. She had been born during the depression, on July 7th, 1929, and had grown up during the austere years of World War II, when food rations went to soldiers fighting overseas in Europe and Japan, and her family enjoyed their prosperity with the enthusiasm of people who remembered what it was like to not have that choice.

After the war, she and her two sisters lived with their parents on the outskirts of Canada’s largest city. She was the youngest of three girls: Lois, Mary, and my grandmother, Phillis Joyce Hicks; though Auntie Lo and Aunt Mary called her Joyce or Joy or Jo. I called her Granny.

The economy was thriving after the war, and they lived a comfortable life, without wanting for anything. Before the war, her father played professional hockey for the Toronto MapleLeafs. In those days, professional sports were more of a competitive hobby than a profession. Hockey players had the same respect as today’s athletes, but without a paycheck. To take care of his family, Great Grandpa Hicks worked for the Canadian Railway. After the war, he became a railroad manager, based in Toronto, and would retire after working there most of his life. Their family wanted for nothing.

My Granny had a few drinks and a good time on night in 1954 and became pregnant. She married the man and gave birth to Wendy Anne Rothdram on August 14th, 1955. The man liked Scotch on the rocks, without the inhibitions of children, and was an artist who would rather draw funny sketches than work for more money doing what he didn’t enjoy. They separated some time between 1955 and 1957. We never learned the exact date, but that’s not important, because the paperwork was never completed. One day in America, Granny received a letter stating that she was still married, in Canada.

To summarize Granny’s approach to everything: she celebrated her divorce 35 years late with a shrug and a laugh and a glass of Scotch whiskey on the rocks. Granny didn’t worry about her past, and she worked hard to prepare her future, so she could shrug and laugh at almost any news.

Granny hadn’t been able to afford taking care of Wendy on her own, so in 1957 she joined her sister and brother in law in America. Auntie Lo had married a French Canadian, Robert M. Descio, from Prince Edward Island, a rural area near Nova Scotia in the French speaking eastern half of Canada. They were living in a Baton Rouge Louisiana, an hour upriver from New Orleans, America’s second busiest port.

Uncle Bob managed the United States division of Bulk Stevedoring Company, a French Canadian Company based in Montreal. Stevedores are laborers in shipping ports; they load and unload cargo ships. Back then, before computers and government regulations changed the industry, stevedors were known to be rough men, physically strong from lifting cargo boxes every day, and happiest dark barrooms after work. They would have fought with sailors from all over the world who visited the same dark barrooms while on shore leave; at the time, one of America’s most popular comic character was Popeye the Sailor, who fought with Big Bluto in port towns. Bluto may have been a Stevedore, before they unionized and had rules against such behavior.

Ships from all oceans in the world can reach New Orleans, via the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico. Some of those of ships bypass the Crecent City, and trace the C-shaped bend in the river bank as they continue up The Mighty Mississippi River to progressively smaller ports. Baton Rouge sits 135 river miles away; or 85 miles by Interstate 10.

Frenchmen like Uncle Bob had been coming to our state since the 1700’s. We were named after France’s King Louis and Queen Anna, using the French word for “and” to join their names, Louis y Anna, the first French explorers sailed across the Atlantic Ocean, around the tip of Florida, where they battled pirates of the Caribbean to enter the Gulf of Mexico and the port of New Orleans, named after Orleans, France.

Explorers passed New Orleans and continued up the Mississippi River, a wandering, serpentine body of water so wide it seemed to still be the ocean. They sailed 135 miles, and discovered a natural widening of the river that would make a good port, more protected from hurricanes than New Orleans. On a bend in the river they saw a tall tree on the bank, stripped of branches, like a giant stick, stuck in the mud. Native American tribes had stuck that stick there to mark the boundry between their tribes, the Frenchmen noted, as they named the river bend after that baton rouge, which is French for Red Stick. That’s how my hometown became Baton Rouge, a tribute to Louis y Anna.

Loiusiana’s history was America’s history, too: our port was crucial during the American revolution and the civil war – which many locals still call the War of Northern Aggression. One of the many wars since Euopeans first traveled up the Mississippi River in the 1700’s led ot Louisiana Cajuns. The confusingly named French and Indian War was when France fought England with the help of Native Americas; the British were fighting against the French and Indians. To confuse matters, the French Canadians living in Nova Scotia bordered the British Americans living in New England, and they were called the Acadians. It may have been because of this confusion that the British asked the Acadians to leave, and the French Canadians from Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia began a 3,000+ mile journey south to the French settlements near Lafayette Louisiana. They were farmers and fisherman who learned to coexist with the Native Americans, and over 200 years their combined customs, food, and music became what we call Cajuns.

Jambalaya tells the story of Cajuns; it’s is a classic Cajun dish of rice cooked with seafood or wild game, that originated as Spanish paella. The French had slaves cooking for them when they first lost Louisiana to the Spanish; the slaves stayed, and cooked for the Spanish. Spain had only sent men to colonize Louisiana; and the Creoles, a mix of Spanish and African and Cajun, learned to cook Spanish paella using local ingredients, like seafood. The Creoles remained when the French regained control of Louisiana, and the French added their techniques of browning sausages and they included Cajun spices, and in all of that confusion they were simply trying to ask for dinner. Jamon is French for ham, a la is over, and ya is an African word for rice; the French asked slaves to make Spanish ham over rice, jamon a la ya, and jambalaya evolved.

Throughout its history, Baton Rouge has been judged by outsiders and seen as a mistaken stop on the way to or from New Orleans. In the 1800’s, Mark Twain called Baton Rouge’s state capital an “eyesore,” and in the 1960’s Ignatius Reilly said, “The only excursion of my life outside of New Orleans took me through the vortex to the whirlpool of despair: Baton Rouge.”

Janis Joplin sang about being “Busted flat in Baton Rouge, waiting for a train,” and Maya Angelou’s little brother jumped on a train to escape southern poverty by going to California, but got on the wrong train and spent two weeks in Baton Rouge before returning home. The longest battle of the civil war – 390 days – was fought just outside of Baton Rouge, though most of their time was spent sitting and waiting. A few Confederate soldiers may still be hiding in the woods there, which may be why we turned it into Fort Pickens State Recreational Area. Growing up, I used a metal detector Uncle Bob gave me to hunt for bullets from the War of Northern Aggression.

My hometown has always been a stopping point, somewhere you get stuck on your way elsewhere. We don’t have the color of New Orleans, or the flavor of Cajun lands. Our accent is more southern than French, more of a drawl than a dialect. Uncle Bob didn’t mind; he had lost most of his French accent, and couldn’t be happier than he was in Red Stick.

French grammar is different than English, which causes uninformed people to believe that Cajuns are less educated because they “walk up da’ stair to put on d’er shoe befo’ d’ey watch d’em Saints play football on da’ television.” To me, the Cajuns sounded a lot like Uncle Bob’s family from Prince Edward Island. His sister, Auntie Rose sounded just like my friends’ Cajun grandmothers.

“Merry Christmas!” she’d say every year. “How you are, mon petit ami ?” She’d bring hand knitted socks and sweaters for Wendy and me, and delicate crochet work for Auntie Lo and Granny.

“D’at’s a nice sweater you’re wearing,” she’d say the next year she visited. She would look me up and down, estimate my growth rate, and plan next year’s socks and sweaters.

Like Cajuns, she seemed to always have a drink in one hand and a cigarette in the other. She spoke lovingly and joyfully between puffs and sips. She was Catholic, and may have known that Jesus said that nothing you put in your mouth can be a sin, only what comes out can be sinful. She only spoke about her beliefs once, to tell me that when I was two months old she baptized me in Uncle Bob’s bathtub. No one in my family felt church or baptism was important, so Auntie Rose had taken matters into her own hands. She was a lot like Granny; they even looked alike, but Granny wasn’t French Canadian so she spoke English with Canadian accent, ‘eh.

Also like Granny, Auntie Rose’s words came from a loving source, and she said them while smiling and laughing, without a care for anything other than that moment between the two of you. She had shared her love with Wendy since Granny moved in with Uncle Bob and Auntie Lo, and when I was born she shared her love with me, too. She visited every Christmas, and brought knitting projects to complete while chatting with us as we sat around Uncle Bob’s white-flocked Christmas Tree. We owned a lot of hand knitted socks and sweaters that smelled of Scotch and cigarettes and love.

Their words still slip into my speech as lagniappe, a little something extra, though I still mispronounce “lan-yap.” It’s more of a concept than a word. It’s a gift, usually from a business owner, like a baker’s dozen, but it doesn’t have to be from a purchase. Lagniappe can be any anything offered freely, without expectation, as a gift, meant for the receiver to enjoy. It can simply be sharing a smile, or parts of a story that hopefully pay off in the end.

Uncle Bob loved many things about America, and Lagniappe is one of the things he grew to love about the people in Baton Rouge; they were more his style than the dark barrooms Stevedors frequented in New Orleans. He had met American soldiers when he served in the Canadian navy during WWII and fallen in love with his idea of America. He said that Americans were more generous and more fun than the austere Catholic upbringing in rural Nova Scotia.

Americans had more identity, pride, and esprit de corps than Canadians, he once told me. He said this kindly, and without judgement. He felt that French Canadians split their loyalties between being French and being Canadian – they called themselves French Canadians – unlike the Cajuns who were Cajun and didn’t need to be more than that to be happy with themselves. Of course he accepted the offer from Bulk Stevedoring to move from their Montreal office and manage the New Orleans office.

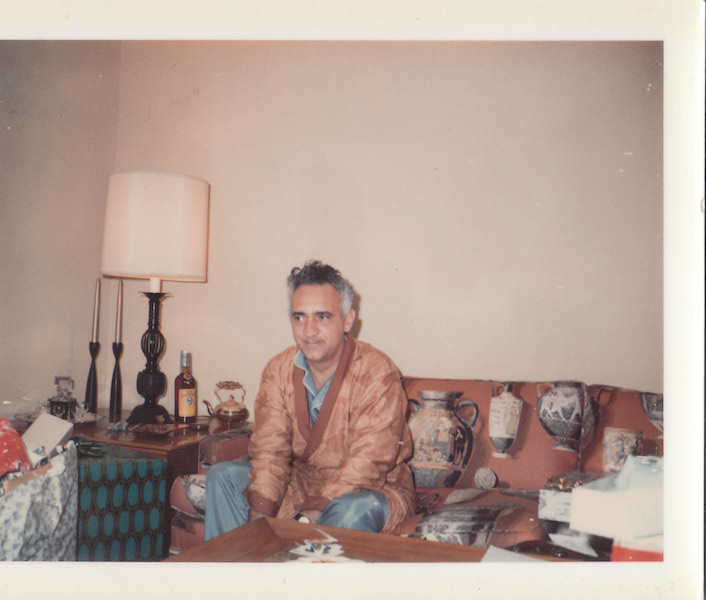

When someone voluntarily comes to America, they are prepared to embrace opportunities. Uncle Bob bought a home in Baton Rouge because it was more cost effective than New Orleans, allowing them to buy a house in a middle class neighborhood and join a country club, which is like a vacation resort where he and Auntie Lo could go on weekends to play golf and dine in the nice restaurant. In theory, they could also swim and play tennis, but mostly they sat in the club’s bar and enjoyed cocktails and laughed with friends.

He was a social person, and loved sharing time with friends, and owning a home near a country club allowed him to embrace everything America had to offer. Buying a home in Baton Rouge was as good of a real estate decision for Uncle Bob as the Louisiana Purchase had been for America; in parts of the state of Louisiana, it’s as if they haven’t heard the news yet, and don’t know that Napoleon had sold all of the land between the Gulf of Mexico and Canada to America for 15 Million dollars. I think we bought it for an uninterrupted supply of gumbo.

Uncle Bob was well liked by most people, regardless if they preferred booze in barrooms or cocktails in country clubs. He balanced being practical with being jovial, and enjoyed sharing cocktails before, during, and after a game of golf. He sometimes enjoyed cocktails in lieu of a game of golf, because though golf was his exercise, it was mostly an excuse to be social. His business was fine, and he was able to leave work at work so that he could enjoy his time at home. He was balanced in the middle class, midway between New Orleans and Lafayette.

He said that business was simply ensuring you had more money in the bank than you spent, and enjoying yourself in the process. He would retire from Bulk Stevedoring after thirty years. Many of his coworkers told me how much they respected him; he brought a sense of balance to their business.

He enjoyed a good time, but never spoke critically of anyone, never cursed, and never promised something he wouldn’t complete, on time. He always wore a watch, and he respected people’s time.

He appreciated simplicity and quality, the type of quality that is useful rather than something to show that you could afford quality. His watch was the simplest looking of Rolexes watches, the Oyster Perpetual. It’s the most cost effective Rolex, but it’s still a Rolex. Someone less satisfied than Uncle Bob may have told people it was a Rolex, to boast that they could afford one. It’s like the doctor at his country club, who asked what do you call a doctor who graduated last in his class? You still call him Doctor.

Words mattered, but intention was more important to him. French was his first language, and his thoughts were French when he first moved there, so he learned to appreciate nuances of words people used. Dining at the country club was more formal than eating in a restaurant. He would joke: What’s the difference between a vase (vaz) and a vase (vace)? Seventy-five dollars, according to the person trying to sell you a vaz.

He didn’t use words to boast, or to speak like his coworkers, or to fit in with other people dining at the country club; he ate, dined, and drank his lunch without needing approval from anyone. Say what you wish, and do what you wish, but be polite and grateful; and, if practical, share.

Uncle Bob loved traditions. Every New Year’s Eve, he and Auntie Lo would watch the Big Apple on television, and see New York City celebrate New Years an hour before us. He’d adjust the time on his Rolex at exactly 11:00 pm Baton Rouge Time; it was never off by more than three seconds from the previous year. He and Auntie Lo would kiss, he’d adjust the wall clocks, and they’d ask if I wanted anything before I went to bed. They’d be snuggled next to each other, snoring, before New Years in Baton Rouge.

They never had biologic children, but they loved Wendy and me and were friendly with many kids in their neighborhood. They were everyone’s favorite aunt and uncle, and their home was a safe and reliable place to eat and rest and play. Thank God I had an Uncle Bob.

Auntie Lo and Uncle Bob were social people, so they became friends with people who shared their interest in liquid lunches at the Sherwood Forest Country Club. The clubhouse overlooked an 18 hole golf course, beautifully lined with old oak trees. There were several tennis courts, and a swimming pool with two bars that started serving cocktails by 11 am. It was fun, social, and the main reason they loved Baton Rouge.

Sherwood Forest Country Club accepted Uncle Bob and Auntie Lo more graciously than the tight-knit churches had. He had gone to a Roman Catholic church every Sunday in Montreal, appreciating the old world elegance of large and well funded churches, but somehow didn’t feel accepted in the buildings that served mass in Baton Rouge. He never spoke negatively about it; it just wasn’t fun, wasn’t a reliable ritual, he had more than enough things he loved doing, and he didn’t need the social interaction of Sunday church. So he played golf with friends at the country club, and Auntie Lo would join him by the pool for cocktails after their game.

Auntie Lo was graceful in spirit. She was a large, cheerful, boisterous woman with a soft heart for me. If you’ve ever seen videos of Julia Child on Public Television, you’ve seen Auntie Lo at her most endearing. She was comfortable swinging her long arms around me, pulling me in for a wet kiss on the cheek that I always had to wipe off, while giggling.

Auntie Rose and Auntie Lo were my only relatives who were physically affectionate, which is why they stand out in my memories as showering me with hugs and food. Auntie Lo always seemed to be near her stove, cooking dinner and keeping the table ready with a never ending supply of freshly cut carrots to meringue cookies and Italian custards to Louisiana gumbo simmering in her largest cast iron pot, an invitation for anyone to have second servings. Even a simple can of tomato sauce was, as she said, “doctored up” with a few extra ingredients and a little love.

Wendy and Granny lived with Uncle Bob and Auntie Lo for a few years, while Granny looked for work. Auntie Rose would visit a few times a year, using her 4 or 5 weeks of vacation to maintain her family ties. She was like Santa Claus; every Christmas we looked forward to seeing our smiling little French aunt, and seeing what she had knitted for us this year. Auntie Rose was love, with a passport and knitting kit. Like with Granny, Auntie Rose’s love was shared as she sipped Scotch on the rocks.

Wendy started going to school, and Uncle Bob would decorate her room with ribbons from her swim meets, and trophies from her tennis matches. From Wendy’s perspective, this was home, and Uncle Bob was more than an uncle, he was her only male role model.

Granny found stable employment as a secretary in one of Baton Rouge’s chemical plants, CoPolymer Rubber Manufacturing, in an area north of downtown nicknamed Chemical Alley because of the refineries that turned oil to gas, and manufacturing plants that turned lower quality oil to plastic or rubber. One of Louisiana’s natural resources is oil, and barges brought shiploads of it from offshore oil rigs every day; Chemical Alley was stable employment, and could grow with America’s seemingly unlimited demand for gas and plastic.

In Baton Rouge, almost everyone knows someone who works in one of the manufacturing plants. As a kid, I remember seeing things differently when I realized that the miles of building with smoke billowing out all day every day was where Granny worked, not in a garden with plants. I couldn’t understand why anyone would choose to work inside of a manufacturing plant along Chemical Alley; but I didn’t have to pay rent or mortgage as a kid.

When Wendy was five or six years old, Granny bought a small home in a low-income part town, directly under the Baton Rouge airport flight path. An airplane flew directly overhead every few hours, coming so close that her walls shook from engine noise. The noise was so loud that you couldn’t hear a person speaking; when an airplane passed, you’d stop speaking and wait for sound waves to stop rattling the kitchen cabinets. This lasted up to a minute, and we’d automatically resume talking without commenting on the interruption.

Granny raised Wendy in that home, a three bedroom house with 1,100 square feet of living space. It was surrounded by an acre of grass and trees, and bordered on two sides by a ditch that flowed with natural water all year long. Granny’s back yard had an ecosystem of minnows, crawfish, tadpoles, crickets, caterpillars and butterflies, squirrels, sparrows, owls, bats, and a enough insects to keep a kid busy for years. At night, you could hear crickets chirping peacefully.

Granny could walk Wendy to a free public elementary school, and later a free school bus would take her to a public high school, where she could play sports and each lunch for free. You could view them as poor or fortunate, depending on your perspective. Wendy felt poor, but Granny saw the glass as half full, of Scotch, with room for more, after bills were paid.

Granny’s coworkers said she was feisty, quick to share her thoughts, but never unkind. Unless she thought someone deserved a quick flash of her temper, then the middle finger of her tiny hand quickly communicated her thoughts. When it was her turn to drive their carpool to work and another driver cut her off or didn’t use their turn signal she would give them the one-finger thought with a few curse words that quickly and effectively communicated her thoughts about their poor driving.Their are rules for society, and she was adamant about following rules; this wasn’t ‘Nam, it was Baton Rouge.

She lived by a code without having to say she lived by a code. It was obvious that her code included following rules that allow society to function politely. When you know the rules, you can use them to your advantage, and be independent. Granny understood the price of freedom, and paid it without a second thought.

She was frugal and conservative with her money. She had to be, as a single mother on a secretary’s salary, to pay for the mortgage, electricity, gas, food, clothes, and booze. And, she liked having a good time, and did not want to be worried about money. It’s not that she drank to avoid problems, she avoided problems so that she could choose what to do with her time. She enjoyed the comfort knowing that her bills were paid, and that her emotions were stable, so that she did not need a man. She was confident and grateful and happy.

After paying monthly bills would she buy large bottles of Scotch whiskey and cartons of cigarettes, bulk purchases that provided more value for her money than buying smaller quantities as she used them. That was one of the contradictions of that time period; in the 1950’s, after the austerity of WWII rationing was followed by a surge in American consumer product manufacturing and home building, good people viewed vices as commodities, no different than purchasing flour, eggs, and beans in bulk. Through that lens, in that culture, purchasing Scotch and cigarettes in bulk was practical.

Granny enjoyed reading every day. She received popular fiction novels in the mail each month by subscribing to Reader’s Digest, and magazines showing the world through the eyes of National Geographic. She read the newspaper to form her own opinion about politics rather than repeating office gossip, and bought the entire Encyclopedia Britanica, an expensive luxury that filled her bookshelf with thick volumes labeled A to Z, Alphabets to Zoology. She encouraged Wendy to read, but did not have to encourage much: Wendy always enjoyed reading, too.

Wendy’s artistic talents didn’t flourish or weren’t nourished, probably a combination of an unrecognized seed sown in untended soil. Her father hadn’t wanted them, and after Granny moved Uncle Bob was still Uncle Bob, but a 30 minute drive away at a time when both Granny and her in-laws wanted to relax at their own home, with cocktails, after a long day Stevedoring and CoPolymering. Wendy felt lonely, and blamed Granny for her misfortune. She created a narrative in her imagination, idealizing her father, a person with whom she had exchanged a few handwritten notes. She believed her narrative, which created a chasm between her ideal view of how life should be and the reality of living on a limited income with her mother.

Granny’s patience was tested, and her drinking loosened her tongue, further aggravating their relationship. Her practical approach was to give Wendy what she kept talking about, packing her onto a plane and sending her to her father. She arrived at her father’s house, but he told her that he didn’t want her. She returned home, deflated, at 13 years old.

Wendy returned to Granny’s home and enrolled in Glenoaks high school. She had grown increasingly shy and withdrawn, and stopped participating in sports and writing and felt inferior when her grades suffered. Her joys came from outside of school, from a summer camp she attended in Tennessee each year, and from the gardens in Baton Rouge city parks. The Baton Rouge public park system has always been a gift to anyone who takes advantage of them, expansive and abundant and rich with opportunities for hiking, fishing, golf, tennis, biking, playgrounds, and team sports.

Wendy always loved being active outdoors, and she sought comfort by being active. She could ride her bicycle to parks near Granny’s, and years later would share those parks on rides with me. In the summer camp, she thrived with like-minded young women who swam for joy rather than competition, played games for fun rather than because there were rules, and didn’t pressure her to be more than she was. Those were her friends, fellow women who were carefree, and they respected each other. She maintained friendships as penpals during the school year, and saw her friends every summer. One of them named their first daughter after Wendy; she was loved, in Tennessee.

Wendy matured into a physically attractive teenage girl, with long blonde hair she kept as neat and organized as her handwriting. She was physically fit from her outdoor activities and sports, and because she wasn’t thin like Granny, she filled her clothes in a way that would have attracted the attention of my father. They met my dad at Glenoaks High School when she was 16 and in 11th grade, and he was 17 and in 12th grade. He would tell me how “fine” she was.

I think she gravitated towards his strong personality, maybe seeking a male role model that she didn’t have with her father, and missed from Uncle Bob. She always avoided the topic. When asked, her eyebrows would narrow, her eyes would close slightly, and her jaw would tighten. She would either remain quiet or walk away, leaving no doubt that she wouldn’t discuss it further, and she never told me how I became a part in her story.

Return to the Table of Contents.