Stevie Nicks is Fine

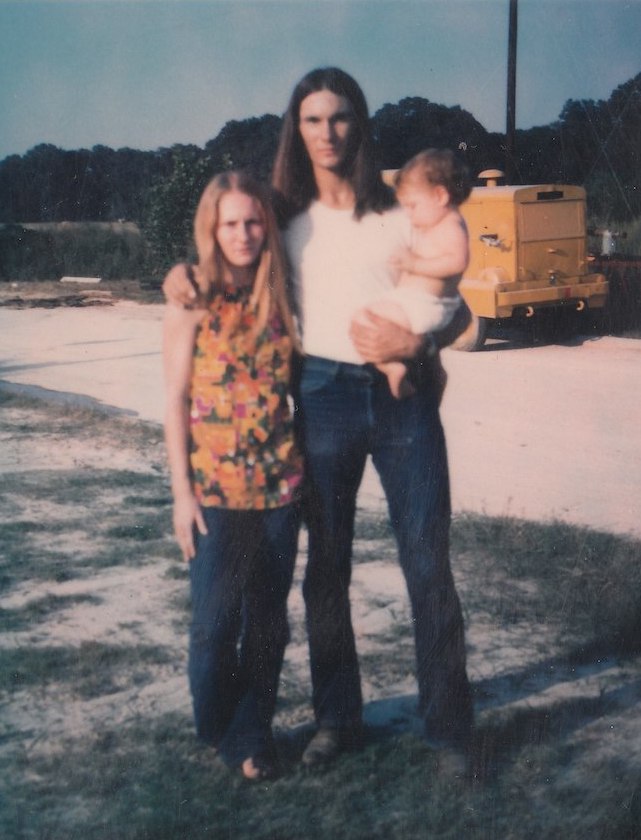

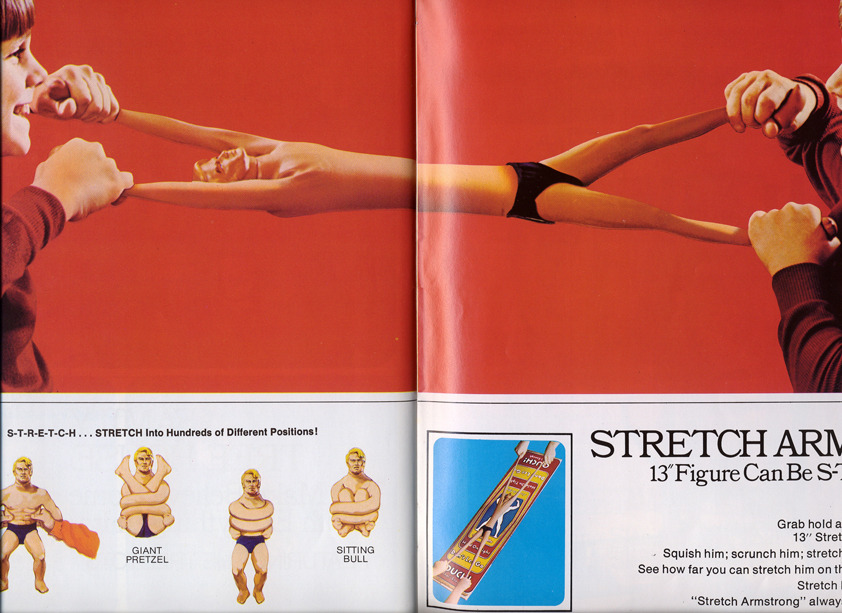

My first memory of my grandfather was a few weeks after my first memory of my dad. I was four years old, the first year that Stretch Armstrong toys were advertised on color television, and I had been in a hospital, Our Lady of the Lake in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, recovering from a head laceration and severe loss of blood after falling from a fence at my foster father’s farm. He, my PawPaw, and my Uncle Kieth had rushed me to Our Lady of The Lake where I stayed for a few days. Before then, I didn’t know who Stretch Armstrong was; but, after watching television in the kids’ communal playroom- the first time I had seen color television, and the first time I had played with other kids so it was remarkable – I was enthralled by the commercial of kids pulling Stretch Armstrong across him across their chest like an exercise band and laughing when he sprang back to normal size. I had to have one! I must have told everyone I met about Stretch Armstrong, and a few weeks later, my dad brought one to me at PawPaw’s farm.

It was dark outside, and we had already eaten dinner. I was nibbling on one of MawMaw’s chocolate chip cookies when I heard my dad’s deep and distinct and loud voice, a voice I recalled before I had visual memories of him. I carried my half eaten cookie into the kitchen and saw PawPaw standing in the door that led to the carport and my dad standing in the light, next to PawPaw’s cage of chirping crickets. PawPaw was telling my dad he couldn’t come in, that it was against the judge’s orders, it wasn’t his weekend. But when my dad saw me, he pushed PawPaw aside and called to me in his deep and loud voice.

“Justin! Goddamnit!” he boomed. “I mean Jason! Come here son, I brought you something.”

I began to obey, but PawPaw stepped in between us and repeated that my dad wasn’t allowed there, and asked him to leave until next weekend. My dad looked down at PawPaw angrily, and pointed his finger into PawPaw’s chest and told him he’d better get out the way, that he brought me a gift and was going to give it to me. I was his goddamn son! he said, then he called to me again. But I was frightened by the shouts, and confused because PawPaw wasn’t smiling or talking to me.

My dad’s voice brought MawMaw into to the kitchen with their daughter and son-in-law, Linda White and Craig Black. MawMaw held me, and Craig and Linda stood by PawPaw, and they all said he should leave. He didn’t, and his voice got louder and his finger flew more fiercely, though I don’t recall what he said. Suddenly, he shouted something and pushed PawPaw, and Linda rushed towards him and beat his chest and shouted at him to get out. He pushed her aside and grabbed my arm, and PawPaw and Craig grabbed him and tried to get him to let go as MawMaw grabbed my other arm and tried to pull me free. I was stretched out with both arms open, like the kids pulling Stretch Armstrong on television, but none of us were laughing. They were all screaming at each other and pulling on me, and I started screaming in pain and fear. I was only four years old, but I could scream as loud as any adult when I was hurting; you could ask PawPaw and Kieth how loudly I screamed on the way to Our Lady of the Lake, and I’m sure they’d agree.

Linda and Craig’s baby girl began crying from the back bedroom, and Linda stopped pummeling my dad and rushed to get her baby, and the adults stopped what they were doing and looked at each other with what should have been self-reflection and a little embarrassment. Things seemed more stable, and Craig left to join Linda and their baby.

I was bleeding from a small scratch on my arm, so MawMaw went to the bathroom to find band-aide and hydrogen peroxide, and PawPaw told my dad he could talk with me in the carport for five minutes. MawMaw returned and doctored my scratch, and I went outside to join my dad sitting on the hood of the truck PawPaw and Uncle Kieth had used to take me to the hospital a month before; the seat was still stained with my blood.

I showed my band-aide proudly, bragging of how MawMaw said I was brave and strong, just like my dad. He liked that, and told me that all Partin me were big and strong, and that he loved me and brought me a gift. He held up a paper bag from the shopping mall, and pulled out a box that was almost a Stretch Armstrong. He smiled awkwardly and said, “I think this is what you wanted…” He said it almost sheepishly, differently than you would have imagined after witnessing him a few moments before.

I quickly saw that it wasn’t Stretch Armstrong, it was his evil nemesis, a dark black alien who also stretched and oozed back into shape. He would have been for sale on the shelf next to Stretch, and my dad was notorious for making mistakes with names and what other people wanted, so it was an easy mistake. I corrected him, and told him that Black Stretch was fine. We opened the box together and tested him, and though my dad could easily stretch him, I couldn’t. I tried and tried, and must of seemed disappointed or frustrated, because my dad said that Black Stretch was stronger than I was then, but that I’d grow bigger and stronger, just like him and my grandfather. I listened, then pulled on Black Stretch a few more times, but I didn’t get strong enough to stretch him before my dad’s five minutes were up.

PawPaw came to the door as stood there as my dad hugged me and told me he loved me before walking off the carport and disappearing into the dark driveway. From the darkness, I heard his booming voice tell me he’d see me in a week. His car lights came on and blinded us, so I waved goodbye to the darkness and went inside with PawPaw and had more cookies with MawMaw, then went to sleep on their couch with Black Stretch cradled in my arms.

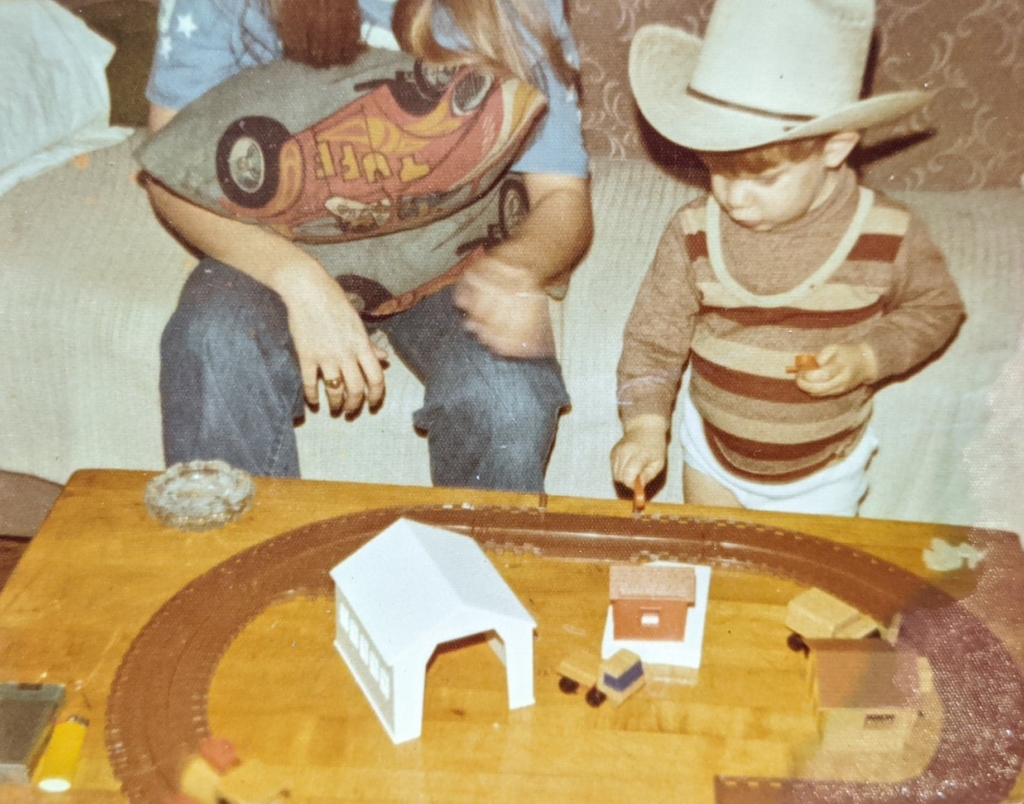

A few weeks later, my dad picked me up to stay at his house for the weekend. I wore a cowboy hat MawMaw had given me, not to block the sun, but to hide my stubbly hair and large scar across my head. My dad laughed at my hat and put me on his shoulders and said I could ride to his farm like a cowboy. When we arrived at the house that evening, he even let me carry his shotgun, just like a cowboy. It was a double barrel 12 gauge loaded with rabbit shot, and was so heavy I could only hold onto the stock with both hands, letting the barrel dangle down near my dad’s head. Riding on his shoulders in my cowboy hat and carrying a shotgun made me feel like the biggest, roughest four year old in all of Louisiana.

We walked from his house to the nearby woods and into the swamp. He picked me off his shoulders and took his shotgun back when we reached the drainage culvert under a big road and bent down so he could crawl through with the shotgun held above his head, and I walked behind him, holding my cowboy hat because it stuck off my head just enough to hit the top of the culvert. On the other side, he put me on his shoulders again, and we walked through more swamp until we reached higher ground and a small trail, probably made by deer and used by raccoons and alligators, he said. We passed the trail, because we didn’t use trails or walk the same way twice, and he took me off his shoulders and we bushwhacked through the thick briars and trees draped with Spanish moss. We stopped briefly to nibble on a few wild blackberries that he pointed out to me, then we continued bushwhacking. A few minutes later, we arrived at his pot farm in a clearing he had made that spring.

I helped him pick weeds, and he explained to me that he was separating the male from the female plants to get sensamilia; though I didn’t understand what he meant, it felt good to have someone as big and strong as my dad speaking to me gently and explaining life. He told me that’s what dad’s do: guide their sons. A little bit later, he told me it was almost dusk and that we needed to leave.

I rode on his shoulders back to his house, but he carried the shotgun. I had lost my hat – I don’t remember how – and I was wearing a spotlight headlamp and carrying a huge battery the size and weight of a brick that would keep the spotlight shining until we got home. My job was to scan the field in front of us, and to stop when I saw eyes glowing back at us. When I did, and after we confirmed it was a rabbit or something edible, my dad would aim the shotgun and, like an expert marksman, instantly kill whatever was in his sites. He’d field dress the rabbit and put its carcass in a sack with the others, and that night he showed me how to clean rabbits and make rabbit stew, and how to chew slowly so I didn’t chip a tooth on any shotgun pellets we may have missed; I learned well, and only chipped my tooth once in the years that followed.

The next day my dad took me to see his dad, who everyone called Big Daddy. I had thought my dad was the biggest person in the universe, even bigger than Uncle Kieth, but he looked as small next to Big Daddy as PawPaw had looked next to my dad and I looked next to PawPaw. But, unlike my dad, Big Daddy was smiling. No matter what my dad said, Big Daddy kept a subtle smile that was more noticeable than a smirk but not as obvious as a grin. And he had bright blue eyes that I’d see when he stooped down and look me in the eyes and talk with me as if nothing else mattered in the world. He memorized me, and I instantly liked him and told him how many rabbits we killed, and how I carried the shotgun. I may have suggested that I shot a few of them in the way kids’ memories embellish fun times with their dads.

Big Daddy said he was proud of me, and that he had a gift for me. He handed me a bag from a department store, and inside was a fancy new fishing rod with a reel and a small tackle box with the metal spinning baits that I knew wouldn’t work on PawPaw’s cane poles. A fishing reel was a whole new world for me, and I focused on going through the tackle box while my dad and Big Daddy talked.

I don’t know why, but my dad began speaking loudly again. I looked up and saw that Big Daddy was smiling as my dad’s voice kept rising, but when my dad poked his finger up into his dad’s face, Big Daddy stopped smiling and slowly reached to his hip and pulled out a hunting knife. He didn’t look angry or raise his voice, but he held his knife low, near my dad’s stomach, and said he’d gut him like a deer if he didn’t move his hand and shut his mouth. That’s the moment I knew that Big Daddy was even bigger and stronger than my dad; and, to this day, the only time I’ve seen my dad stop talking when someone asked.

We left in a hurry, and I barely had time to collect my fishing rod and tackle box. On the ride home, my dad kept saying things about not wanting to be like his father, that he’d always be honest and open with me, and never hide anything from me. I don’t recall all the words he used, but he’d use the same phrases so often over the next few years that I remember hearing the concept for the first time that day. My dad would always say that he wanted to be a better dad than Big Daddy, and he always wanted be honest with me. That’s why he took me farming, he said, and why he was teaching me so much. I didn’t understand anything he was saying, and I was still focused on my new fishing rod and didn’t ask questions.

Back at PawPaw’s, I tried using my new fishing rod. PawPaw taught me how to set up the fancy reel, and reminded me how to tie a knot onto the hook, something he had been teaching me for a while buy I hadn’t mastered yet. He tied my knot after I tried a few times, then burned off the loose end of the knot with his cigarette and hooked the hook through an eyelet on my new rod so that I could carry it to the pond. I carried it much more easily than my dad’s shotgun, and strutted around proudly showing off my fancy fishing rod. I was ready to go fishing, I said. PawPaw laughed and grabbed his cigarettes and a beer and said he was ready, too.

“Come on, Lil’ Buddy. Let’s go try out that fancy fishing rod.”

We walked onto the carport and scooped up a jar full of crickets and walked towards the back barn, past the newly repaired big gate, and plopped down on a log that PawPaw had placed on the bank of the pond. He set his beer and cigarettes down, and showed me how to cast my new rod, but the pond was so small that casting didn’t make sense. And, every time I tried to practice, the reel’s string just got all knotted. I became frustrated, and PawPaw laughed and held out the extra cane pole he had brought, and let me practice tying the knot. He didn’t have a cigarette lit yet, so he pulled out his pocket knife to cut off the loose end. I told him about Big Daddy’s knife, and how Big Daddy got my dad to shut his mouth, and said that I’d like a knife, too. PawPaw listened to me, stayed quiet for a few moments, then put his arm around me and said, “I love you, Lil’ Buddy.” I told him I loved him, too; and to this day I know that was the most truthful thing my four year old self had ever said.

It was becoming dusk, so PawPaw and I collected our fishing rods and began walking back towards the house. MawMaw always saw us coming, and that day was no exception. She opened the back door when we got close, and she smiled radiantly and said, “I’m gonna get me some shuggah!” I giggled in anticipation, and she took two steps forward, and said again, “I’m gonna get me some shuggah’!” and I giggled even more loudly. She took two more steps closer, almost touching me, and squatted down and reached out and grabbed my shoulders and pursed her lips out with newly applied bright red lipstick and I laughed and squealed as she pulled me closer and planted shuggah all over my cheeks and left the red marks I’d feverishly wipe off in the living room mirror before dinner. I could already smell chocolate chip cookies baking, and I knew it would be a fun evening.

After I wiped off the red shuggah marks, I saw Black Stretch and grabbed him and pulled with all my might and stretched him at least an inch. PawPaw us, and reminded me that I had grown so much stronger that I could now stretch Stretch. I thought about this, and remembered how frustrated I had been after a few days of trying unsuccessfully to do what the kids on color television had; but now, as irrefutable evidence of me growing, I could stretch him. I beamed pridefully and tried to open my knife again. Though I couldn’t open it, at least I didn’t feel frustrated now that I knew I’d soon be strong enough.

We had dinner and a few cookies, and afterwards I played with my new knife and Stretch while PawPaw drank a bottle of beer or two and MawMaw watched her television and Craig and Linda went to their bedroom with the baby. I still couldn’t open my knew knife, even after PawPaw oiled it. My fingernail wouldn’t stay under the small notch used to pull up the blade, and I became frustrated again – my earlier patience long forgotten. I put it aside in disgust, and picked up one of PawPaw’s screwdrivers lying around the house, and held it like Big Daddy had held his knife. I put it in Stretch’s face, and told him to shut his mouth. When he didn’t, I lowered the screwdriver and thrust it into his belly, just below his rib cage, where I’d begin the cut that would gut a rabbit.

To my surprise, Stretch leaked. He wasn’t invulnerable like on television. He bled a thick, clear gel that I anxiously tried to pack back into the hole I had made, but all I did was spread the goo across his belly, and as I held him tightly more goo squeezed out. Before long, Stretch was limp and my hands and pants were wet and sticky from whatever chemicals were inside his rubber skin. I began crying, frustrated that nothing was working out like I wanted, and worried that I had lost my stretching toy. PawPaw came in and found me and the deflated Stretch, and smiled and held me and waited patiently for me to stop crying, then he put stretch in the freezer and said that should make the good more thick, and in a few minutes we could try to fix him with some super glue.

We never fixed Black Stretch, though I did learn that goo gets thicker in the freezer, and that super glue makes your fingers stick together, and that knife punctures can kill. We didn’t burry Stretch right away, and for a few days I slept with his lifeless body until I finally agreed with MawMaw that it was time to throw him away. I bravely did it myself, holding his limp body over the trash can and apologizing for stabbing him. PawPaw rested his hand on my shoulder as I said my final farewell, and after we returned inside he asked what I had learned, and I told him that I learned my knife could kill things, so I should always use it carefully. For some reason, that lesson stuck with me more than the realization that I was growing stronger, maybe because the loss of my short-lived toy drove the lesson more deeply.

The next few visits with my dad and each return to PawPaw’s went similarly, though we didn’t see Big Daddy again for a while. Instead, my dad took me to see Big Daddy’s mamma, Grandma Foster. We brought her a rabbit from the rabbit cage my dad had built in his back yard in one of the months I didn’t see him, and she thanked us and told me how much she appreciated my dad visiting her and how much I looked like him. She was sweet and always smiling, like Big Daddy. She had bright blue eyes like him, too. But she was tiny, barely bigger than me, which probably made her seem sweeter in my mind.

Grandma Foster made smothered rabbit, though I didn’t like it. There weren’t shotgun pellets in my dad’s cage rabbits, so I wasn’t concerned about my teeth, but, as I would learn later in life, not all grandmother’s cooked as well as MawMaw. Grandma Foster may have been a sweet little old lady, but she was no chef, and the rabbit was tough and tasted like burnt cooking oil. My dad didn’t seem to mind, and piled ketchup on his portion and kept telling me to eat more so I’d grow big like him. Somehow, I managed to keep eating while Grandma talked.

“Your daddy lived with me when he was your age,” she said, beaming with pride at having her grandson and great-grandson visit. “He and Edward would go hunting and bring back deer and elk. You’ll get to do that one day, too.”

My dad explained that Big Daddy had a hunting camp in the mountains of Arizona and another in Colorado. They used to go hunting together, he said, but hadn’t ever since I was born. He said he’d like to take me with them, and Grandma asked me if I’d like that. I said yes, of course, though I didn’t know what an elk or a mountain or a cabin or an Arizona was; I hoped it tasted better than Grandma’s smothered rabbit.

On the way home, my dad pointed to another house, and told me that’s where Wendy had lived. I wasn’t sure who that was, but I followed his finger and saw a house that looked like most other houses in that neighborhood, except that it had a huge stately oak tree in the front yard. I was unimpressed: none of those tiny houses had a big fence and barn and fishing pond like my house, and I was anxious to return to MawMaw’s cooking. They didn’t live far away, so I was home soon and wouldn’t see my dad for another month.

My next visit was around Christmas time, and PawPaw let my dad keep me for almost a week because of the holiday. On that visit, we killed another rabbit – one I had unfortunately named and grown to view as a pet – and took it to another grandmother, Mamma Jean. Her real name was Norma Jean Partin, “like the movie star!” she said, meaning Marylin Monroe’s real name. Mamma Jean and Aunt Janice laughed at that and made a joke about that Norma Jean being Kennedy’s girlfriend, then they began making rabbit jambalaya while my cousin Tiffany and I played with her new baby brother, Damon.

I had grown a lot in the few months since I met my dad, and I was starting to recognize differences in faces. I could see that my dad looked like Aunt Janice and Mamma Jean and Tiffany. And me, according to everyone who saw me. We all had dark brown eyes; only Damon had blue eyes, like Big Daddy and Grandma Foster and Linda’s baby. I began to form a confusing definition of “family” that, in my mind, meant both people who looked like me and PawPaw and MawMaw and Craig and Linda; Damon looked like their baby, and I figured that all babies were family.

Back in the kitchen, Mamma Jean added rice to the rabbit and closed the lid, so we had time to spend together. Never lifts the lid on simmering rice, she said, so we had at least 20 minute to talk before dinner. We sat in the living room, and Mamma Jean asked to see the back of my head. She parted my hair and inspected my scar, and said she’d like to give me a haircut after dinner. She was a hair stylist, she said, and that I could use a proper haircut for Christmas.

Speaking of Christmas, Aunt Janice said, she had a gift for me. She handed me a wrapped present, and I tore open the paper and held up the framed drawing that was inside. It was a boy flying a kite, shaded in black. Look closely, she said. She pointed at the edge of the drawing, and I saw that it wasn’t shaded, but had a lot of writing that made it look shaded. Tiffany spoke up and said that it was my name, Jason Partin, written again and again until it made the image, and that they had made it for me. It was supposed to be me, she said, and Aunt Janice said it was important to remember my name and to know that I was part of their family. I said thank you, like MawMaw had taught me, though I was slightly disappointed to receive a gift I couldn’t play with.

Everyone swapped a few presents, and then talked about things I couldn’t remember while Tiffany showed me around. I saw a desk covered in family photos, just like at PawPaw’s, but I didn’t see a picture of myself. Aunt Janice saw me looking, and began telling me names of everyone in the photo, asking Tiffany if she remembered this person or that one, and telling me how important it was to know our family. I was about to ask where’s my photo, but Aunt Janice suddenly laughed and picked up a photo with Mamma Jean and a big man wearing a cowboy hat and carrying a rifle, and they laughed and told a few stories about him and other actors and actresses. She seemed so excited by that photo that I told her about my cowboy hat and how I had lost it hunting for rabbits, and how Big Daddy gave me a fishing rod, but for some reason no one talked about him.

Mamma Jean asked my dad some things I don’t recall, and he kept raising his voice in response and Mamma Jean seemed to get angry. Aunt Janice told him to lower his voice and not upset the children – I think she meant Damon – but that led to my dad speaking more loudly and without stopping for other people to say anything. I don’t remember what he said, and I never learned what they argued about or what made Mamma Jean so upset. I do recall her telling my dad that Jesus loved him and that she’d pray for us, and him telling her to shove her bible up her ass, and Aunt Janice yelling at my dad to leave. We left so quickly that I didn’t have time to hug anyone goodbye.

Back at my dad’s house, we settled in for Christmas eve. His house was Spartan and without Christmas decor, and I asked him if we should leave cookies out for Santa Claus even though we didn’t have a tree. He pointed at me and told me that Santa Claus was a bullshit lie, just like Jesus. I argued otherwise, and he told me to wait until morning, that there’d be no presents, and that would prove to me there was no Santa.

The next morning, I walked into the living room and he was already there. He waved his hand around the empty room and told me that he was right, and that adults lie to kids about Santa Clause and Jesus, but he’d never lie to me. And, he had a present for me – he did, not Santa – and had even wrapped it in brightly colored newspaper comics but without tape. I tore it open easily because it had not tape, and was thunderstruck when I realized I now owned and held a brand new, kid-sized, single-shot, bolt action, .22 rifle. I held it in both hands and pointed it at the wall, something I couldn’t do with the shotgun, and stared at it with so much awe that I couldn’t even speak. We spent the rest of the day shooting empty beer cans in the back yard. It was the best Christmas I had ever had.

A few days later, back at PawPaw’s, they had left a few presents for me wrapped under a small tree that PawPaw had cut from his farm, and he and MawMaw and Linda and Craig and ???? gathered around and let me open my presents. They had opened theirs on Christmas, but that Santa had left some for me. I told them that Santa Claus was bullshit, and MawMaw told me not to use that word and that we’d talk about it later, but that I should have fun opening presents. I said ok, and tore through the wrappings and inspected my new toys and cowboy hat with so much joy that I forgot about Santa. I put on my new hat, and thought about how I had a hat and a rifle, just like Big Daddy in the picture with Mamma Jean.

Later that day, we grabbed some crickets and went fishing with the cane poles. PawPaw told me he had been waiting to give me something, but now seemed like a good time, and he handed me a small box from his pocket, and inside it was a pocket knife just like his but smaller, an Old Henry two-blade knife I’d later recognize as popular with boy scouts and other kids with their first knifes. My eyes widened in excitement, and I took the knife from PawPaw’s hands with reverence. But I was soon disappointed, because I wasn’t able to open the folded knife, just like I wasn’t strong enough to stretch Black Stretch. PawPaw told me not to worry, that he’d show me how to oil the knife and make it easier to open.

“And you’ll be getting bigger and stronger, Lil’ Buddy,” he said, smiling at me. I asked him when I’d get bigger, and he laughed but didn’t answer because suddenly his cork began bobbing, partially dipping under the water and sending ripples towards us. He pointed to it and said, with a contagious sense of anticipation, “Watch the bobber, Lil’ Buddy.” The red and white bobber danced on the water surface and sent ripples towards where, and I took the cane pole from him and held it tightly with both hands.

“When it goes down fast and deep, pull up on the pole!” It did, and then I did, and suddenly the pole was bent in a beautiful arc, and the line zigged and zagged from the fight of the world’s biggest and most powerful pond brim. I pulled as hard as I could, and yanked the leviathan out of the water. It flew through the air and flapped around on the ground, and PawPaw gently put his foot on it until he could pick it up and hold it for me to safely remove the hook.

He reminded me to be gentle so it would live when we put it back in the pond, and I removed the hook just like PawPaw had taught me before. He smiled and told me I did a good job, then tossed the brim back into the pond and stuck his hands in the water and rubbed off the fish slime. He told me it would get bigger for the next time we fished, just like I’d get bigger and be able to open my knife.

About a week later, I pulled out the Old Henry and slid my now longer thumbnail into the slit on its biggest blade, and triumphantly opened it and showed the exposed blade to PawPaw. He told me he was proud of me, and asked me to show him how to close it safely. I moved my fingers out of the way and put my palm on the back of the big blade and rotated, not pushed, the blade back into the handle. I held the closed knife up for PawPaw to see.

PawPaw hugged me and told me he was proud of me, and asked if I wanted walk with my knife to get cigarettes and play on my favorite tree, a huge stately oak with branches that stretched out forever and had a crooked branch that bobbed up and down with me in it, just like a cork bobbing on the surface of a pond. I put my knife in my pocket and held PawPaw’s hand and walked to our favorite tree across the street from a convenience store, and after PawPaw bought cigarettes we played and bobbed in branches of that tree until it was time to go home for dinner and chocolate chip cookies.

The next few years progressed similarly, with most of my time spent at PawPaw and MawMaw’s, Mr. & Mrs. Ed White, with their children Linda and Craig Black, and the baby who’s name I can’t recall. I never used Big Daddy’s fishing rod again, and can’t remember what happened to it.

The next time I thought about it was 1979, the year Big Daddy went to prison, and the year my dad took me to see Stevie Nicks, and I learned that she was fine.

“Stevie Nicks is fine!” my dad told me when he picked me up. I was listening to him as I reached up and crawled into his new truck. He seemed to have a new car or truck or jeep every time I saw him, and this truck was so big I had to use both hands to pull myself into the passenger side of the long, couch-like truck seat. I put my weekend backpack on between us, and used my feet to push aside empty beer cans and candy wrappers in the floor, and listened to my dad tell me about Miss Nicks.

“She’ll change dresses between every song, just for us!” he assured me as we drove off. We sped down the road, past my stately oak tree and PawPaw’s convenience store, and towards downtown Baton Rouge. My dad rummaged around the floorboard as he sped up the interstate onramp, telling me he had her new album to listen to. He found it and handed it to me and told me to play it.

Stevie Nicks was the lead singer of one of the world’s most famous bands, Fleetwood Mac, and their new album was “Rumors,” which is still one of the best selling albums of all time. My dad was enamored by her, and had talked about her incessantly the last time I had seen him and he had bought tickets for Fleetwood Mac’s Rumors tour. Their Baton Rouge show coincided with his weekend with me, and, true to his word, he always included me in whatever he was doing. He was honest and transparent with me, like he had promised three years ago and seemed to remind me every time we got together to tend his farm or wrap pot in bags for him to sell. I had become a deadly shot against rabbits with my .22 rifle, and had even cleaned a few with my own Old Henry knife; I had it with me, like I always did, just in case there was trouble that my dad couldn’t handle.

One of my favorite things to do with my dad was listen to music in whatever car or truck he was driving that month. He’d sing along and smoke a few joints and we’d laugh together, and I was anxious to be around him and singing along, so I pushed the eight track forward with both hands and tried to push the “play” button with one finger, like my dad could, but I had to hold two fingers closely together and push with both hands to push it all the way forward. As soon as I did, my dad raised a knee to hold the steering wheel while he quickly rolled a joint and lit it and inhaled deeply. He put his hands back on the wheel and exhaled as the first song played, and he began singing along with “Second Hand News.” I tapped my seat like a drum and laughed with him and breathed deeply as smoke filled the truck cab.

We reached the new Baton Rouge Centroplex by the time my dad finished that joint, and parked near the levee separating us from the Mississippi River. He kept the radio playing and rolled another joint and opened a can of beer from the partially empty six pack on the floorboard. After a joint and two or three beers, we had listened to the entire Rumors album and were ready to go inside.

I stepped out of the truck, accidentally kicking empty beer cans onto the ground but shutting my door without noticing. My dad stopped me and told me to put the cans back inside, that it was wrong to litter. I did, happy that my dad always showed me right from wrong, and to this day I’ve never intentionally littered; some lessons sink in as deeply as a screwdriver sinks into Stretch’s stomach.

I was in a great mood after being in the truck for three joints with my dad, so even picking up trash seemed fun. I looked around for extra trash someone less responsible than us may have left, picked up something I don’t recall, and shut the truck door and followed my dad to the 10,000 seat Centroplex. Once inside, he bought a beer and held my hand as he pushed and shoved his way to the front, talking about how fine Stevie Nicks was the entire time. He found a spot so near the stage that I could see the texture on the center microphone.

As the crowd packed in, people began bumping into me and spilling their beer on my head, so my dad picked me up and put me on his shoulders, just like when we were hunting rabbits, and I was able to look all around. I had never seen that many people before! All of Baton Rouge must have been there. Through the haze of smoke, I saw thousands of people who looked a lot like my dad, with long hair and shaggy beards and smoking joints. The ones near me would cheer to me and slap my dad on his back and say that it was awesome that he spent quality time with his son. He’d agree, and they’d share a joint, and I simply stared at the lights through the smoke and watched people from my perch high above them, happy as I had ever been.

Suddenly, the lights dimmed around us and grew brighter and I lurched backwards, because my dad had released my legs in order to applaud and cup his hands around his mouth to shout, like all everyone seemed to be doing. I regained my balance and clapped and shouted, too. When the band came on stage, everyone shouted and my dad moved to see them, and when Stevie Nicks came on stage he shouted loud enough for everyone in Baton Rouge to hear. They began playing, and over the next few joints I fell in love with Miss Nicks, just like my dad had.

My dad was right, she changed dresses between songs and seemed to dance just for us, especially because we were so close to the stage. She even smiled at me! I will never forget that moment, just after she had been twirling in a flowing dress that made her look like a butterfly flittering across the stage. She twirled back to the microphone and held it and smiled at me and sang us a song as thousands of people sang with her. I was seven years old, but I knew a life-altering experience when I felt one, and I sat high upon my dad’s shoulders and felt taller and bigger than anyone in the Centroplex that night. It was more magical than anything I could have seen on television.

After the show, we stumbled back to the levee and somehow found my dad’s truck. He fumbled for his keys, dropped them and cursed, and rummaged around the dirt for them. After locating the door handle and keyhole, he opened the door and pulled me up and into his lap.

“Justin – I mean Jason – you’re gonna help me drive to Sonny’s.” Sonny was my dad’s friend we visited sometimes, and he only lived a mile from the Centroplex, just off the levee road by the new State Capital building.

“He’ll have cocaine. That’ll sober me up enough to drive home,” my dad mumbled. He was probably joking a bit, but I still felt so good after the show that I was excited to try driving. My feet wouldn’t reach the pedals, so I sat on his lap and he used his legs for the gas. It was a new truck with automatic transmission, unlike the jeep he had tried to teach me to drive before, so it was easier, he said. All I had to do was hold the steering wheel and help him not drive off the road or into the oncoming lane. He started the truck, lowered the steering wheel shifter into “drive,” and we pulled onto the levee road with his hands on the bottom of the wheel and my hands on top, dutifully steering us to Sonny’s house.

My dad had to help us turn off the levee road and towards the state capital – it was hard to turn that big truck – and soon we pulled into Sonny’s driveway. It was late at night, but Sonny’s light was on and he came outside to see who had arrived. He was wearing the same bath robe I remember from the past few times we visited, and he was happy to see us. He told me hello, and even said my name right on the first try.

Inside, Sonny had a vinyl album of Rumors, and he and my dad laughed as my dad used it to roll a joint from Sonny’s weed. It wasn’t sensamilia, so he scraped it up the album with the edge of his pack of rolling papers and let the seeds tumble down. After a few scrapes, he had a neat pile of pot and was able to deftly roll a joint while Sonny laid out a mirror and a few lines of cocaine. They lit the joint and passed it as they alternated snorting lines of coke. And, just like my dad said, he seemed to sober up and start laughing again, and by the end of the joint he was ready to go. We said goodbye to Sonny, and he told me to ride in the passenger side because he was good to drive home.

I was tired and had crashed by the time we arrived home. My dad shook me gently, and I looked up through droopy eyes and said I wish I had some cocaine to wake up. His finger quickly came up and into my face, and his eyes narrowed and his booming voice told me to never use that word, and to never tell anyone about Sonny or cocaine or what we did with his friends. His mood change was so drastic that it snapped me awake as if I had done a round of coke with him and Sonny, and I promised to never tell anyone what we did with his farm and friends. He smiled and said that I was a good son, and that he loved me. We went inside and I instantly fell asleep.

I awoke in the new house. It was new to me, at least. My dad was renting it and using it to dry that year’s marijuana harvest. It was a huge house, big enough for an entire family. A high school was across the street, so my dad kept the windows covered with thick drapes. I had to move them aside to see where I had woken up.

I learned that Cousin Donald was staying there, and so was Uncle Keith. Donald was in his wheelchair and already sipping a beer, and Keith was impatiently waiting for my dad to finish making breakfast so we could go see Big Daddy. They were all talking about how Big Daddy was going away, and Donald seemed especially worried. He kept asking if we’d loose protection, and talking about how he had to stay with my dad because Hoffa or Marcello had blown up his dad’s house; Donald was Big Daddy’s nephew, the son of Uncle Doug, his little brother. Kieth was my dad’s little brother; though they were called little brothers, all of them were bigger than anyone else I knew. Except for Donald; he had gotten in a drunk driving accident and broken his back, and his legs had shriveled from lack of use since then.

Kieth and my dad and I loaded into a new car, not the truck, and Kieth kept stroking it and talking about it with eyes wide open. I don’t recall the car, but even 40 years later Keith would smile nostalgically when he described the new leather seats and new car smell. It was the most coveted sports car among teenagers, and Kieth was still in high school back then, and too young to drive yet. In his mind, my dad having that car was both the coolest thing and frustrating. Big Daddy had been buying my dad new cars every time he wrecked one for years; but now Big Daddy was going to prison and wouldn’t be around to buy Keith his first car. Kieth was upset, and hoped my dad wouldn’t wreck that one before he could drive it.

Like I promised, I never told Kieth that my dad already let me drive his new truck, and would probably let me drive his new car, too.

We met Big Daddy near the Teamsters headquarters, and as usually he and my dad argued. I don’t recall what about, but we left after Big Daddy pulled a knife out again. Even then, as my dad rode away stoically, Keith was less concerned about my dad and Big Daddy’s knife as he was impressed by my dad’s new car. I wasn’t interested in Big Daddy’s knife that time, either. Kids get used to everything.

A few visits later, after my dad had wrecked the sports car, we tried to go see Big Daddy in prison. He was in Texas, about a three joint drive away, and when we arrived the prison was closed. My dad shouted at the guards that he wanted to see his father, but they kept reminding him of the posted visiting hours and asking him to lower his voice. We turned around and went home, and my dad spent most of the drive telling me stories about his dad that I don’t recall. But, I remember him reemphasizing that he’d be different to me, that he’d be honest with me, and that he loved me. I told him that I loved him, too. I did. And I trusted him. After all, he had been right; Stevie Nicks was, indeed, fine.

The reason I probably recall those meetings with Big Daddy so well, besides him pulling a knife both times and giving me a fishing rod the first, is that coincidentally the first time I saw him pull a knife was ell shortly after Jimmy Hoffa was released from prison and disappeared. It was a topic I didn’t understand, but that every adult around me talked about often. Ever since that time, my family seemed to talk about Hoffa and Marcello more and more, or at least I grew old enough to start noticing or remembering patterns. I heard that Big Daddy had been shot, and Uncle Doug’s home had been blown up, and Big Daddy had even killed some guy named Audrey Murphy to keep Hoffa in prison before he was released; and after Hoffa was gone and Kennedy was dead and the FBI no longer needed us, we’d probably loose our money and houses and not get any new cars before Keith would be old enough to drive. Kieth was always upset about that part.

For me, I wasn’t worried. I didn’t need a car yet, and most of my time was spent with PawPaw and MawMaw; and by 1979 also with Wendy and Uncle Bob and Auntie Lo. But, they were a different family, and a different story. 1979 was the year Big Daddy went to prison and a judge granted Wendy custody of me.That’s the next chapter of my part in family; the story of how I met my mother, Wendy Anne Rothdram Partin.