Havana

But then came the killing shot that was to nail me to the cross.

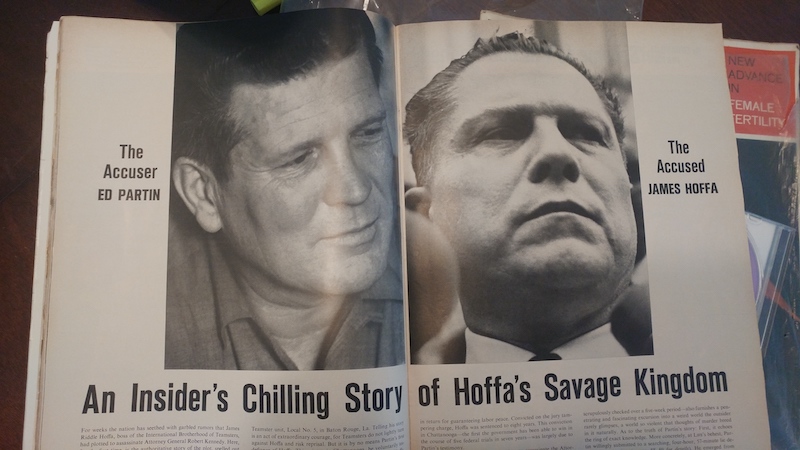

Edward Grady Partin.

And Life magazine once again was Robert Kenedy’s tool. He figured that, at long last, he was going to dust my ass and he wanted to set the public up to see what a great man he was in getting Hoffa.

Life quoted Walter Sheridan, head of the Get-Hoffa Squad, that Partin was virtually the all-American boy even though he had been in jail “because of a minor domestic problem.”

Jimmy Hoffa in “Hoffa: The Real Story,” 1975

I had just landed in Cuba on a 30 day entrepreneurship visa and was pondering my grandfather’s role in President Kennedy’s assassination, when I suddenly felt Wendy was planning to commit suicide; she wouldn’t, and I had no reason to suspect she would, but that was my first reaction when I listened to her voice mail while standing in the small Plaza de San Francisco de Asi, which I was told was one of only two places a gringo could catch public WiFi, even in 2019.

I was wearing a sun faded black backpack with short black scuba fins strapped to the outside, stretching and listening to voice mail by pressing an outdated iPhone 8 tightly against my left ear and poking my right forefinger into my other ear. My head hurt, my back ached, and I was wound up from sitting in confined spaces next to chatty people; it was the first day of what I planned to be a three month sabbatical: a month in Cuba thanks to President Obama’s new visa to promote entrepreneurship (whatever that means) and two months of hopping around Caribbean islands without an agenda. But, half way through Wendy’s voice mail, I slowly stood upright and stared at the phone in my hand. I almost called her right then. I put in my earbuds – or iBuds or whatever they’re called – and listened to her message again, looking for nuances that few, if any, other people would have noticed or understood.

“Hey Jason, it’s Wendy,” she began, followed by a pause.

“I know you’re going to Cuba, but I was hoping to speak with you about my will.”

Another pause.

“It’s not a big deal,” she said quickly and continued at a similar pace, clumping words so they almost sounded as one: “I’d just like to add Cindi as executor because you travel so much.”

She had called about her will several times over the past ten or fifteen years. Every time, she used the same brisk cadence, and it was always just before happy hour in my time zone. She usually rushed words after a few glasses of wine.

Wendy was my mother, Wendy Anne Rothdram Partin. She taught me to call her by her first name when she was a 16 year old mother and I was in the Louisiana foster system. My parents disagree on what happened, but court records show that between 1972 and 1973 I was an infant and living with my parents in one of my grandfather’s houses in a new subdivision, adjacent to the Achafalaya Basin and near the Comite River; he was Edward Grady Partin Senior. My father, Edward Grady Partin Junior, was arrested, tried, and found guilty for possession of opioids with intent to distribute, but was released without going to jail. When he was gone to Jamaica with a gamg of friends to buy the opioids, Wendy abandoned me at a daycare mear her old high school, and fled to California with a man she just met. Judge Pugh of the East Baton Rouge Parish 19th Judicial District family court placed me in the home of a legal guardian, Mr. James “Ed” White, the custodian at Glen Oaks High School, where my parents had met. Wendy returned to Baton Rouge on her own;, divorced my father, and spent seven years fighting the Partins and the Whites in court. She was ashamed of her situation and what she had done, and when she visited me once a month she taught me to call her by her first name so people would assume I was her little brother. Old habits are hard to break, and I still call my mother Wendy.

“And I thought…,” she said. I took two breaths in the pause… “It’s not important. Call me back when you can.”

There was another pause, and a sigh as subtle as the b in subtle.

“Tell Cristi I said hello, and I hope y’all are enjoying San Diego,” she said quickly.

Most people listening would say she forced her tone to seem upbeat.

“If I miss you,” she finished, “Have fun in Cuba and we’ll talk when you get back.”

I rewound the message – an archaic term for cassette answering machines that I still say in my head – and listened two more times. After she said, “And I thought…,” I held my breath… I thought I heard a hint of “I,” beginning but fading before manifesting. I felt she wanted to say more, and for some reason that subtle pause is what triggered my sense of dread that she would commit suicide. It was probably just a coincidence: I had been thinking about Judge Pugh on the flight, and he had allegedly committed suicide in July of 1975, right around when Jimmy Hoffa vanished from a Detroit parking lot, and Judge JJ Lottingger stepped down from legislative law to oversee my custody case in family court for at least the next year; I’m not sure how long he was involved, but my custody records show him helping Wendy as late as 26 September 1976.

I sighed and rotated my left wrist. I glanced at the 30+ year old solar powered Seiko dive watch, modified to be a satellite pager. The technology was cutting edge back then; it hadn’t needed a battery changed or to be wound in three decades, and the charge from an average day lasted six months. I’ve been impressed by small solar cells ever since. But, the plastic parts oxidize and have been known to break unexpectedly, so I replace the thick black corrugated band before every sabbatical. (One of the most dangerous things about deep wreck diving is nitrogen narcosis, and many otherwise skilled divers lost their lives chasing something they were attached to that slipped off and slowly sank to irrecoverable depths.) I had replaced the band at San Diego’s Just-in-Time on Tuesday; it was still on Pacific Standard Time. I could call Wendy back before she passed out that evening.

I sighed again, and my gaze dropped form my phone to my two big feet.

I was her last surviving relative in America. Wendy had her tubes tied long ago, saying she’d never repeat her mistakes again, and she had no siblings. We had a few distant cousins in Canada, and a 93 year old great-Aunt Mary, Granny’s sister (she would pass away in Richmond Hill during Covid-19, at age 94), but they only kept in touch with hand-written Christmas letters year or two after Aunt Mary’s aunt, Aunt Edith, passed away; she was a wealthy childless widow who traveled frequently and kept family threads connected. I was the only one who knew Wendy’s history and mannerisms.

She had only left Louisiana four times in thirty years: our scuba trip to Cancun with my stepdad in 1995, a drive to Chatanooga to visit a childhood friend in the early 2000’s, a flight to Canada to visit Aunt Mary in the mid 2000’s, and a flight to San Diego in 2008, just before the housing crash. In San Diego, we ended our days early. She stayed near me, in a Balboa Park historic hotel and walking distance from the zoo, and was ashamed to be like Granny and Auntie Lo: buzzed by 3, drunk by 4 and sloppy by 5; By 6pm, she was sloshed, and would start apologizing for things that happened long ago. She rarely stayed up past 7 or 8, and by 5am she was perky and ready to go, having forgotten what she said the night before. By 3pm, she’d be laughing and quoting the refrigerator magnet I had bought Auntie Lo in 1989, just after Uncle Bob died, saying: The past can not be changed, but the future is whatever you want it to be. By 4 she’d be drunk again.

As soon as she turned 64, she said, she would begin withdrawing from all her inherited IRA’s and traveling like Aunt Edith had. Not like I did. No offense to Cuba! she said. She wanted to see places like Paris and Dublin and stay in luxurious hotels with fluffy towels and room service, where she’d meet the next love of her life.

She was a Canadian citizen, because she procrastinated completing paperwork and saw no need to become an American. She had lived in the states for 59 years, and despite finalizing her divorce from my father two years after marrying him, kept her married name for 45 years. (She never married Mike, her live-in boyfriend for 17 years; I called him my stepdad in high school, because, like Wendy, I was embarrassed about our home situation and lied about it to friends and teachers.) She didn’t want the hassle of changing her driver’s license, social security card, or the IRA accounts; and she never wanted the name Rothdram, either.

In 1971, a few months before she met my father, she had flown back to Canada to reunite with her father, but he was remarried and had four daughters, and refused Wendy. She said her father said that Granny had made a choice, and Wendy was her problem now. She returned with a memento of her trip that she didn’t show Granny: her father’s thick brown leather belt, with a hefty metal buckle and sharp edges along its entire length, as if it were new and had never been worn. She asked Granny why she kept that man’s last name; Granny, smiling cheerfully with a tallboy of Scotch on the rocks in her right hand and a Kent cigaretted clipped between two fingers of her left hand, said, “Hell, I don’t care what people call us. Change your name, if it would make you happier.” She wasn’t being sarcastic: Granny was perpetually happy; she believed everything was a choice. Wendy listened to her advice, met my dad, the drug dealer of Glen Oaks High School, lost her virginity to him and became pregnant with me, and a few weeks later she became Wendy Anne Rothdram Partin. I was born nine months later, on 05 October 1972.

Wendy was still a Canadian citizen, to become a U.S. citizen required studying for a history and civics exam, and she never enjoyed studying; and, she’d have to revert to her maiden name, Wendy Anne Rothdram, or pick a new one. She said she didn’t need citizenship, that she was happy with her dogs, who didn’t care about her last name and never questioned her about anything nor asked her to temper her drinking. They just loved her for who she was, a flawed person doing her best. She said I could learn a thing or two from Liam and Angel.

Despite her poor choices, Wendy was one of the wealthiest women in America. Granny had been a savy investor, and taught us that a dollar not taxed was a dollar earned, and Wendy inherited Ganny’s retirement accounts when Granny passed away on 20 November 1990.

Granny is buried in a city-run cemetery in Baker, Louisiana, under an ancient gumball tree and only 30 feet away from a small charter school where kids practice brass instruments outside; I’m unsure what she’d say about tuba practice outside of her final resting place, but I’m sure it would have been said with a laugh and a smoke. She said she learned how to have fun from her father, Harold “Hal” Hicks. According to Wikipedia:

Harold Henry Hicks (December 10, 1900 — August 14, 1965) was a Canadian professional ice hockey player who played 90 games in the National Hockey League with the Montreal Maroons, Detroit Cougars, and Detroit Falcons between 1928 and 1931. The rest of his career, which lasted between 1917 and 1934, was spent in various minor leagues. He was born in Sillery, Quebec.

If Granny were alive today, she’d read what Wikipedia had to say about Grandpa Hicks and say: Bullshit. He played for the Maple Leafs and the Bruins, too. What the hell is this Wikipedia thing? Pay for a set of encyclopedias and read a goddamn book; she’d probably then ask for a cigarette and a Scotch on the rocks and her reading glasses, and show me her scrapbook of his newspaper clippings to prove she was right. He died in 1965, retiring as a senior manager of the Canadian railway system; his obituary was shown nationally, and I never had a reason to doubt Granny.

Despite choosing to smoke a carton or two of Kents a week, Granny invested wisely. The IRA’s Wendy inherited averaged 10.7% compounding interest and dividends over 30 years, greater than somewhere between 90% and 95% of all professionally managed funds, according to a few books I read. Wendy hadn’t tweaked Granny’s more than a smidgen here and there. Otherwise, Wendy inherited Granny’s original portfolio, which Uncle Bob had followed, because he trusted Granny’s discernment; Auntie Lo passed soon after, and suddenly Wendy had three inherited IRA’s, plus her own. All leaned towards Exxon, DuPont, Chevron, McDonald’s, IBM, GE, AT&T, and companies with plants or offices in Baton Rouge, New Orleans, and Houston.

For almost thirty years each, both Wendy and Granny had allocated the maximum monthly amount possible in their company-sponsored retirement plans, around 10-17%, depending on congressional laws each year, and also contributed to individual plans in traditional IRA’s. (The Roth IRA wasn’t an option yet; when Wendy and I discussed the pros and cons, she kept a traditional plan. Currently, you can contribute $5,500 if you work for yourself, $17,500 if you work for someone else. Both increase by $1000 after you turn 65. Wendy, invoking Granny’s tone, said IRA limits were “a bullshit incentive to keep people working for someone else,” and she wouldn’t be a slave to Exxon with all those “assholes engineers,” saying that putting up with them is why she drank.) Granny retired from DuPont after 30 years, Wendy from Exxon-Mobil after 27 years. The interest of Wendy’s inheritance from Granny, Uncle Bob, and Auntie Lo compounded for more than sixty years; that’s a lot of money by 2019, and Wendy was a multi-millionaire. According to Wikipedia, she was one of the wealthiest 26,000 or so people, Northern America, which, as an All American, believe included Canada and Mexico. I don’t know all of the advice Granny gave Wendy, but she hadn’t touched the IRA’s since a few poor decisions in the 1990’s. Since then, repeated Granny’s advice of avoiding 10% early retirement penalty on top of income taxes of around 27%.

Until Wendy turned 64, she was, admittedly, on a tight budget. She had just begun receiving social security checks, and that’s barely enough to pay for her air conditioning bill, vet insurance, and wine. We had discussed Granny frequently over the past fifteen years, quoting her parting thoughts: everything’s a choice.

My eyebrows narrowed. My headache felt worse. I shouldn’t worry about Wendy, I thought to myself.

My dad crept into my thoughts.

Fuck, I thought. Shit.

My biologic father, Ed Partin Junior, had gotten out of an Arkansas federal prison in 1986 after losing a battle in Reagan’s war on drugs; passed his GED; earned honor graduate with a dual degree in history and political science from the University of Arkansas in only 3-1/2 years; earned a Juris Doctorate in Arkansas; was invited to speak to congress about legalizing flag burning; passed the Arkansas bar and, without attending school in Louisiana, passed the Napoleonic-esque Louisiana bar exam unique among all other codes in the United States; successfully sued the states of Arkansas and Louisiana to practice law as a convicted felon – a detail he had overlooked when planning his path- representing himself all the way to the state supreme courts of each; and moved back to Louisiana in the mid 1990’s to become public defense attorney. He made local news weekly, both for defending those who had no other defenders; and for frequent DUI’s, fines for contempt of court, shooting a neighbor’s dog, an embarrassing incident after an LSU law school party where he woke up naked, and earning two small brass plaques with his name engraved as part of The Chimes “around the world” beer competition, where you had to drink something like two or three beers from every country that made beer within a year. The plaques said: E.G. Partin. Wendy stopped going to the Chimes when she pulled out her credit card to pay, and the young bartended asked if she were related to Ed Partin, his buddy’s public defense attorney.

In a remarkable coincidence, my dad settled in the town adjacent to Saint Francisville, the appropriately named Slaughter, Louisiana, and bought five acres adjacent to Wendy’s coworker’s home; to their chagrin, he built a barn and chicken coop partially on their property. When they pried into Wendy’s name at work, they were just curious if Ed Partin, the crazy bearded guy caught on film shooing Betsy and her husband away from his chickens with a shotgun, the guy they kept reading about in the about in the paper, was a distant relative of Wendy’s. But, she reacted as if she had PTSD. She was already known to snap at coworkers and tell them to mind their own business, and Exxon’s early retirement offer was generous. She avoided Slaughter, and after my dad stumbled into her favorite cafe she avoided St. Francisville, too.

Shit. Fuck. Shit.

I shouldn’t worry about Wendy. She said she was mostly happy, volunteering at the relatively new West Feliciana Parsih Humane Society, the one next door to the infamous private Angola prison (for decades, it was “the most bloody prison in America”). Though no one but the humane society director and me knew this, Wendy brought a bag of McDonald’s breakfast sandwiches to the Angola work-release prisoners who cleaned dog cages for 15 cents an hour, even in 2019. “They only cost 99 cents each,” Wendy said, “and those poor old black men have those same shitty sandwiches from when we were kids.” (The annual Angola prison rodeo, a tradition predating the prison and perhaps reaching back to Angola plantation, always gave the same lunch in the same brown paper bags to the poor black men: grey bologna and orange cheese between two slices of soggy white bread.) She showed up early in the mornings, before most people were awake, gave sandwiches to the prisoners, chew toys to the dogs, and sometimes found one on death row that she’d take home and foster until the next St. Francisville pet adoption fair. At home, she’d feed her dogs, make lunch, get bored, and open a bottle of wine. She said she drank because she was there was nothing else to do on a hot and muggy day in southern Louisiana, and there were a lot of hot and muggy days in southern Louisiana.

I sighed again, adjusted the time on my dive watch to delay a few moments longer, and and tried calling her back. As usual, her cell phone wasn’t getting reception. She didn’t answer her land line (another archaic word in my head, used for some old phones and in the military, a wire hastily stretched between defense positions to use in lieu of radio or light signals that could be intercepted). I sent a text and an email letting her know I had already arrived in Cuba. I chuckled to lighten the tone, and said that that the cell reception in Havana was worse than at her place, and that I’d only be able to check messages when I came back to Havana every week or two, but to text or email me if it were important. I said I’d stay in Havana longer, if necessary, so we could schedule a time to speak.

Coincidentally, I added, chuckling: I was calling from a public square named after Saint Francis, the patron saint of kindness to animals, and I hoped that put a smile on her face. I reiterated that I’d check messages when I could, and added a perfunctory “I love you.”

I left a voice with Cristi, saying I arrived safely and that the WiFi was less than I had expected, so I would be mostly offline. She had been used to gaps of contact ever since we were in middle school and missed each other for summer vacations, which transitioned to the first war, where I was gone for most of 1990-1991, and my service on America’s quick reaction force under President Clinton after that (we deployed with two hour notice and communication lockouts to prevent media discernment between real versus simulated deployments, and I had been offline for up to six months at at time). Recently, I was a faculty of physics, engineering, and entrepreneurship at USD, UCSD, and an advisor with a few nonprofit organizations incorporating entrepreneurship education into public K-12 schools; I took off once a year or more for one to three month sabbaticals, sometimes for fun and sometimes to work with side-gigs. Clients work with me because I’m discrete, and I don’t post what we’re doing online. In my message to Cristi, I said everything was fine and loved her, paused, and enunciated that Wendy had left a voice mail and I was concerned; I didn’t mention the coincidence about St. Francis, because that would diluted my message and started Cristi thinking about synchronicity; I’d tell her when I got home, and could see her reaction.

I looked up, hung up the phone, and sighed again. I took out my earbuds and held them, inhaled slowly and deeply, and exhaled completely. I squeezed a puff more out, inhaled again, and exhaled in a single, satisfying purge. I packed away the earbuds and glanced around the plaza to see if anyone was paying attention. There were a few handfuls of people scattered here and there, and about half of the people were using their phones, either talking or scrolling. A few were walking around, peering into the bars and chatting with their people about what they saw or heard inside, excited by the prospects. No one seemed to notice much.

I made a decision: I opened my Lonely Planet and called a couple of casa particulars I had circled on one of the airplanes. I spent precious WiFi minutes asking a few questions until I confirmed which had a room with two doors; one was a glass door that opened onto a center, shared courtyard. I told them I’d be there after dinner, and then sent a burst to my circle. (“Burst” was once an encrypted scramble between synchronized frequency-hopping radios in a single-integrated network, ground-and-airborne radio system, the most advanced communications technology known; now burst messages are accomplished by typing a list of names in the “bcc” line of a free email account.) I typed a quick gmail to two thirty-something eco-sports journalists guys, telling them I had arrived and would see them in Vinales in a week or so. I sent WhatsAp to a young illegal climbing guide in Vinales something similar, but in Spanglish. I was more cautious in my wording than most people I know, but most people don’t have my background.

As a side gig, I was a rock climbing guide in remote regions of off-the-beaten-path countries, a fractal spiraling into the most untouched places left on Earth; when we ran out of space horizontally, we climbed vertically to where few, if any, ventured. The limestone cliffs of Cuba were only a thousand feet or so, but the rock was some of the best face climbing in the western hemisphere, and views of Vinales farming valley were astounding, worthy of photos for expensive outdoor adventure magazines.

The views eco-journalists wanted to use their visa to write articles for their national magazine gig, but they also wanted to dig deeper into the politics that prevented Americans from visiting Cuba, and touch on the bigger picture of a small island trying to become sustainable, and use that as a lesson for Earth. They risked their visa if they strayed too far from eco-journalism, which isn’t much more than paid advertisement for tourism. They used me to help meet a few local guides. I’m notoriously “hands off,” reticent about details, especially over the phone or via texts or emails. Like Wendy, I’m allergic to paperwork, so assistants handled our travel insurance, per requirements for all tourists who may have to use Cuba’s state-run hospital system in an emergency; it prevents people from other countries from having a travel-focused healthcare plan. Rock climbing’s not a big deal, but it’s still illegal in some countries because it’s deemed an unnecessary risk. Many governments monitor tourists, and you never know who’s listening, or when a local law enforcement officer or person with a grudge or some other motivation, who could arrest you or testify about anything you said or wrote.

If that sounds paranoid, crazy, or szcizophrenic, you may be right. But, to put my caution in perspective, Jimmy Hoffa, the world’s most powerful labor leader and one of the wealthiest and most well known men in America not a Kennedy, went to prison in 1966 for a few words spoken to my grandfather, Edward Grady Partin Senior. They were in a private hotel room and guarded by Hoffa’s inner circle, and Hoffa uttered out a single sentence implying Big Daddy bribe a juror in the Test Fleet case against Hoffa. He timed the sentence with the motion of patting an envelope of cash in his back pocket, saying $20,000 should do it. The room was swept for bugs by the best electronics goons money could buy, but nothing can stop a person with a hidden agenda; a few months before, Big Daddy was arrested for kidnapping and manslaughter, but two days later U.S. Attorney General Bobby freed him, in exchange for infiltrating Hoffa’ inner circle and finding “anything of interest” that Bobby could use against his nemesis. Ten months after Bobby’s brother, President John F. Kennedy, was assassinated, Hoffa was found guilty based solely on my grandfather’s testimony about a few words Hoffa uttered in presumed privacy. Hoffa’s lawyers were the best money could buy who were willing to work for people like Hoffa, Marcello, Traficante, and all the main mafia families in each state, yet they still couldn’t stop Hoffa from being sentenced to 11 years in prison because of a personal vendetta. Newspapers dubbed the fight between Bobby and Hoffa “The Blood Feud,” and Bobby showcased my family nationally, sharing billing with newly appointed President Johnson and his family, and Big Daddy was dubbed an all-American hero. From prison, Hoffa promised to forgive $121 Million of mafia debt if “anyone” could get Ed Partin to change his testimony “using any means” as long as he “remained alive,” to recant or sign an affidavit swearing that “spoiled brat Booby” used “illegal wiretapping.” (Hoffa always called Bobby Booby.) I grew up under federal protection, a gift from Bobby and FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, even after Bobby was assassinated in 1968, for as long as Hoffa remained in prison. As a 16 year old little girl Wendy was subjected to harassment and threats by strangers trying to get Ed Partin to recant his testimony; our address was listed in the Baton Rouge phone book under Ed Partin, and though I can’t say for certain, I’m sure even the lowest level of Carlos Marcello’s sycophants could read, or at least knew someone who could. It’s no wonder she had a nervous breakdown and fled. Given my background, I was cautious whenever I was another country’s soil, no matter how crazy it sounds to people who don’t know my Partin history.

Hoffa’a army of resourceful attorneys appealed his sentence for two years, but they lost their 1966 supreme court case, Hoffa versus The United States. The only one of nine judges to dissent against using Big Daddy’s testimony was Warren, a 40 year veteran of the court, having overseen landmark cases such as Roe vs Wade, Brown vs The Board of Education, and the case that gave us Miranda Rights. He was a household name by the time of Hoffa’s 1966 case, because he been chairman of a committee to investigate President Kenendy’s assassination, and the 1964 Warren Report was debated by almost every household in America. (Warren mistakenly said Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone when he shot and killed Kennedy, and that Jack Ruby acted alone two days later, when he shot and killed Oswald, who was wearing handcuffs and being escorted out of the Dallas police station and shot Oswald on live television; 110 million people witnessed it, so no one doubted Ruby’s guilt, but most people doubted that either Oswald or Ruby acted on their own, and to this day most people suspect a conspiracy. The 1979 congressional JFK and Martin Luther King Junior Assassination Report, though kept classified until President Clinton released the first part in 1992, reversed the Warren Report and said that Kennedy’s murder was the result of an organized effort, and the three suspects with the means, motive, and method were Jimmy Hoffa, New Orleans mafia boss Carlos Marcelo, and Miami mafia boss and Cuban exile Santos Trafacante Junior.) Chief Justice Earl Warren made decisions based on information presented to him, and in 1966 he was one of the first people to look at my grandfather’s criminal history and the details of his testimony against Hoffa, and only one of nine judges to see a problem with sending Hoffa to prison based solely on one person’s testimony, especially a person like Edward Grady Partin Senior.

This is what Warren said about Big Daddy, and the process by which America monitors personal conversations:

“Here, Edward Partin, a jailbird languishing in a Louisiana jail under indictments for such state and federal crimes as embezzlement, kidnapping, and manslaughter (and soon to be charged with perjury and assault), contacted federal authorities and told them he was willing to become, and would be useful as, an informer against Hoffa, who was then about to be tried in the Test Fleet case. A motive for his doing this is immediately apparent — namely, his strong desire to work his way out of jail and out of his various legal entanglements with the State and Federal Governments. And it is interesting to note that, if this was his motive, he has been uniquely successful in satisfying it. In the four years since he first volunteered to be an informer against Hoffa he has not been prosecuted on any of the serious federal charges for which he was at that time jailed, and the state charges have apparently vanished into thin air. Shortly after Partin made contact with the federal authorities and told them of his position in the Baton Rouge Local of the Teamsters Union and of his acquaintance with Hoffa, his bail was suddenly reduced from $50,000 to $5,000 and he was released from jail. He immediately telephoned Hoffa, who was then in New Jersey, and, by collaborating with a state law enforcement official, surreptitiously made a tape recording of the conversation. A copy of the recording was furnished to federal authorities. Again on a pretext of wanting to talk with Hoffa regarding Partin’s legal difficulties, Partin telephoned Hoffa a few weeks later and succeeded in making a date to meet in Nashville, where Hoffa and his attorneys were then preparing for the Test Fleet trial. Unknown to Hoffa, this call was also recorded, and again federal authorities were informed as to the details.“

Warren’s missive of dissent was lengthy, even for a missive. After a few more paragraphs of ranting about Big Daddy, Warren cited a few words given to Big Daddy by FBI agent Walter Sheidan, a former campaign adviser for John F. Kennedy and head of the FBI’s Get Hoffa squad under Bobby Kennedy, that would be cited again and again for the next sixty years: “anything of interest.” In that paragraph, he also for mentioned my grandmother, Norma Jean Partin, my Mamma Jean, though not by name.

“Pursuant to the general instructions he received from federal authorities to report “any attempts at witness intimidation or tampering with the jury,” “anything illegal,” or even “anything of interest,” Partin became the equivalent of a bugging device which moved with Hoffa wherever he went. Everything Partin saw or heard was reported to federal authorities, and much of it was ultimately the subject matter of his testimony in this case. For his services, he was well paid by the Government, both through devious and secret support payments to his wife and, it may be inferred, by executed promises not to pursue the indictments under which he was charged at the time he became an informer.

This type of informer and the uses to which he was put in this case evidence a serious potential for undermining the integrity of the truthfinding process in the federal courts. Given the incentives and background of Partin, no conviction should be allowed to stand when based heavily on his testimony. And that is exactly the quicksand upon which these convictions rest, because, without Partin, who was the principal government witness, there would probably have been no convictions here. Thus, although petitioners make their main arguments on constitutional grounds and raise serious Fourth and Sixth Amendment questions, it should not even be necessary for the Court to reach those questions. For the affront to the quality and fairness of federal law enforcement which this case presents is sufficient to require an exercise of our supervisory powers. As we said in ordering a new trial in Mesarosh v. United States, 352 U. S. 1, 352 U. S. 14 (1956), a federal case involving the testimony of an unsavory informer who, the Government admitted, had committed perjury in other cases:

This is a federal criminal case, and this Court has supervisory jurisdiction over the proceedings of the federal courts. If it has any duty to perform in this regard, it is to see that the waters of justice are not polluted. Pollution having taken place here, the condition should be remedied at the earliest opportunity.”

Hoffa went to prison after he ran out of appeals in the supreme court. From that point on, his case, Hoffa versus The United States, would be cited by lower courts and used to justify unspecific wire tapping. I’m not a lawyer, and I read on Wikipedia that the fourth amendment says, among other things, “warrants must be issued by a judge or magistrate, justified by probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and must particularly describe the place to be searched and the persons or things to be seized.” A walking bug sprung from a Baton Rouge jail cell could violate a lot of things.

As for the sixth amendment, I’ve never studied it. For all I know, it excludes people like me from inalienable rights granted to others. I believe Chief Justice Earl Warren knew more about the sixth amendment than I do, so I’ll assume something about using Hoffa’s trial seemed to violate it, maybe the surprise factor Walter Sheridan and Bobby Kennedy used, having Big Daddy stand up in the court room and shocking Hoffa. According to everyone in the room, Hoffa gasped and said, “My God! It’s Partin!”

All of the jurors overheard him, and when Big Daddy was cross examined for three days he wooed them with his strawberry blonde hair, sky blue eyes, subtle but persistent smile, and charming southern accent. He described the context of what Hoffa said, mentioning the padded envelope Hoffa had patted in his back pocket, and safe full of padded envelops that no juror had seen. They believed Big Daddy’s word, and in 1964 they had quickly returned from only a few hours of deliberation and found Hoffa guilty of attempting to bribe a juror in the 1962 Test Fleet Case, escalating what was a seemingly benign state-level case to the federal charge of jury tampering.

The consequences of supreme court verdicts are higher than one person’s sentencing: they impact all subsequent cases with similar wording. Warren had overseen the case that led to Miranda Rights, the one centered around the sixth amendment and the use of witnesses, and reminds everyone being arrested that the right to an attorney and the right to remain silent; I assume Warren knew a thing or two about the forth and sixth amendments, which is why he said Hoffa’s case should have never reached the supreme court, and why he wrote a missive for posterity to ponder. As for The Miranda Rights, it’s hard to deny that the world would be a more peaceful place if more people practiced their right to remain silent.

I don’t know if the waters of justice are still polluted, nor do I know what Warren would have said if he knew the ghosts of Big Daddy and Jimmy Hoffa would resurface in 2001. Hoffa vs The United States became a cornerstone of a foundation upon which President George Bush Junior built Patriot Act, the act rushed through congress after 9/11 and brilliantly abbreviated: “The 2001 Act for Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism.” The Patriot act justified monitoring cell phone messages of hundreds of millions of people without a warrant, looking for “anything of interest.” Because it used technology, not just of a room of FBI agents, The Patriot Act used software to scrub messages looking for anything of interest by anyone using cell phones in America; similar justifications were used for monitoring people and embassy’s globally. Not only did a few words uttered by Hoffa land him in prison, those were the words Walter Sheridan offered as advice when prepping Big Daddy. Sixty years later, those words crawled off a page in the annals of the American justice system and touched millions of people’s private messages; justified locking up terrorists in Cuba’s Guantanamo Bay without attorneys, interviewing witnesses against them, or a trial; and paved the way for American’s torturing prisoners using the CIA-approved waterboarding method.

In one of the most hilarious coincidences I’ve ever learned, Bush’s leading legal advisor was a Harvard law professor named Jack Goldsmith, who used to be Jack O’Brien before changing his name after law school; he is the adopted son of Chucky O’Brien, Jimmy Hoffa’s adopted son and long-time suspect in the FBI’s ongoing investigation into Hoffa’s disappearance.

When Jack was in law school at Yale, he changed his name to his biologic father’s, because Chucky O’Brien was still under FBI investigation for Hoffa’s disappearance and other mafia-related shenanigans. (Almost all mafia film charatertures of a short, squat, bulldog, fiercely loyal to Hoffa or one of the families, are based on Chuckie; Joe Pesci would portray him in The Irishman, and had, humorously, jumped up to slap Craig Vincent on behalf of Robert DeNiro in Scorce’s Casino film. Chucky despised Big Daddy, and cursed his ghost up until Chuckie’s death in 2020, a year after his adopted son exonerated his suspicion in Hoffa’s disappearance, and almost exactly thirty years after a team of burly men heaved Big Daddy’s casket into his grave in Baton Rouge’s Greenwood Cemetery.) Jack disagreed with many points of the Patriot Act, but did his job under presidential orders. (No offense to Jack, but I always mention anyone who reports to a boss and does something they believe is immoral or unethical as an example of why entrepreneurship can provide freedom to improve the world.)

In short: words have consequences, and after a while all you can do about it is laugh and watch what you say or write.

A simple word or two overheard and out of context could get you put in jail. Under Cuba’s national health coverage, unnecessary and risky sports are illegal. The law wasn’t enforced, like American marijuana laws or President Clinton’s “don’t ask, don’t tell” military policies in 1992 weren’t enforced, but there was always a possibility that one law enforcement official with a bug up his ass could use an obscure law to confiscate a farmer’s land or to make an example out of a gringo or two. In the 2000’s, President George Bush Junior had personally been involved in a $14 Million pursuit of Tommy Chong, from the comedy duo Cheech and Chong, for helping his daughter start a glass pipe business that everyone had to call Chong’s Bongs; he was arrested in his pajamas at his California home by a federal task force one morning. He spent nine months in federal prison for what was legal in California but illegal federally, sharing a cell with The Wolf of Wall Street; that’s no joke. Every year, at least a few American tourists are arrested for things like littering, spitting, marijuana, illegal sexual choices, or even traffic violations; they are detained in countries with a grudge against Americans, and have been publicly whipped with a cane (Singapore’s penalty for spitting on a sidewalk) put in prison for a year or more, etc. Iran still has laws allowing a hand to be cleaved off if you steal a piece of bread, and many countries have barbaric practices to get the devil’s homosexual seed out of you, America’s not innocent: after 9/11, we arrested and detained dozens of terrorism suspects based on intercepted messages, and detained them in an old American navy base in Guantanamo Bay, amd tortured them for years.

The Guatanamo prisoners were only three hours west of where I was checking voice mail and sending messages from my cell phone. They had been there for more than fifteen years without an attorney, and had been tortured by American soldiers under guidance from above. A few say the ends warrant the means; anyone who says waterboarding isn’t torture should try it for a while. Everything the prisoners said was used against them.

I planned to visit Guantanamo at the end of my trip, to see the base for myself, and to chat with a few locals and listen to their perspectives. Maybe I’d meet a chatty U.S. soldier and buy them a mojito, and listen to what they have to say. But, on my first day in Cuba, I was more concerned with not knowing how Cuba monitored air waves, or if local law enforcement harbored resentment about America forcing a base on their soil in Guantanamo Bay.

Many Cubans were still resentful of President Kennedy’s botched Bay of Pigs invasion that killed some of their fathers, and distrustful of seemingly benign tourists after America killed Cuba’s adopted son, El Che Guevara, using CIA operatives in Bolivia; not to mention several CIA attempts to murder Fidel Castro. A few old Cubans may even remember their father’s talking about President Rosevelt’s Rough Riders killing their great-grandfathers, and many may have more stories, whether true or not, and you never know which local official harbors deep seeded resentment against gringos. I grew up in the deep south, where history teachers in public schools taught us that the civil war was “the war of northern aggression,” and I didn’t know what Cubans were taught in school. We’re all just a pile of flesh, and our minds are slaves of other people’s words.

Many people in Latin America are justified in distrusting America, especially if they recall the 1980’s, because of several invasions by America’s Guard of Honor, the 82nd Airborne, on call to act without congressional and on presidential commands for 30 days. In the 1980’s, the 82nd Airborne All Americans invaded Latin American again and again. The most viewed internationally was over Christmas of 1989, when the 82nd parachuted into Panama, over-through the country, and arrested President Noriaga as part of President George Bush Senior’s continued war on drugs (he had been vice president under Reagan, who escalated the war and even authorized CIA to plant mines in the civilian ports of Nicaragua). To capture him alive, teenage paratroopers surrounded his compound with stadium-sized speakers and blared American hard-rock music 24 hours a day, seven days a week, depriving Noriaga and his defense forces of sleep until they surrendered: they repeatedly played Van Halen’s 1984 album and it’s two classic songs: “Jump!” and “Panama.” Who could forget that? I’d bet money that, to this day, Noriega and his personal guards remember the All Americans well, and know the lyrics to all songs in Van Halen’s 1984 album by heart.

In 1985, the All Americans landed in Grenada; in 1983, The Dominican Republic; in 1979, Honduras. The 82nd was busy in Vietnam before presidents set their sites on Latin America, and for more than a decade the Vietnam era jokes about the 82nd’s continued, t-shirts and bumper stickers, things like: “Death from above” and “kill ’em all! Let God sort ’em out,” but now joking about the Latin American islands that a few plane fulls of paratroopers could easily overthrow. Many local law enforcement officials were former military and knew the jokes, and they may harbor resentment. The slang word, gringo, stems from Latin Americans wanting Americans in green uniforms to go away; sure, spend your greenbacks here, but then go away.

If I were unlucky and a Cuban police officer with a grudge recognized one of my tattoos, any infarction could be used against me as a lesson to others. On my inner left bicep are large American airborne wings, on my inner right wrist is an AA. I joke the is stands for Alcoholics Annonymous whenever someone is invasive enough to ask, but it stands for All Americans. There are many tattoos like it, but that one is mine; it’s copied from the AA on my 82nd combat patch, the one I had hand-sewn on my first desert camouflage uniform using dental floss and the last needle in my repair kit; I did it before authorized, like a lot of us, soon after the ground war of Desert Storm began, and just after my platoon led the capture of Khamisiya airport. We were hit by the only chemical weapon explosion of the first first Gulf war, and felt we deserved a combat patch before it was officially awarded.

That war was Desert Shield and Desert Storm, 1990-1991, when America shifted our sites from Latin America to the Middle East after Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait. After returning from fighting in Panama’s jungles for 30 days, the same team of 82nd paratroopers took off fromNorth Carolina on 03 August 1990 and landed in 117 degree heat, and a few hundred teenagers armed with M16’s and a couple of Humvee’s with .50 cal machine guns and TOW-II missiles, drew a line in the sand that stopped the largest tank force the world had ever known; a few months later, they and a similarly armed French unit led the front line ahead of 560,000 allied soldiers.

In a funny quirk, I was told I was the youngest out of all 560,000 soldiers (I joined at 16, began basic training at 17, and turned 18 just before jump school. I knew my history before I joined and chose the All Americans, though I doubt an arresting officer would want to hear it.

In WWI, the 82nd Infantry was formed, and was the first time a federal force had members from every united states, and forward-thinking people dubbed them the All Americans to help us heal from the civil war. In WWII, the 82nd Infantry became America’s first paratroop unit, and was famous for parachuting into remote regions and standing up against Hitler’s Panzer tank forces faster than any other response; no one doubts that the All Americans turned the tied of war and helped stop genocide. After embarrassment about the 555 “Tripple Nickle,” an African American paratroop unit in the still segregated American military, forward thinking people installed anti-segragation laws into military doctrine; that was long before the supreme court reviewed Brown vs The Board of Education; some people see military regulations as a way to advocate global peace and an improved democracy, by leading by example to all of the Americans who rotate threw the military and learn to live coexist peacefully with each other. In 1992, a political cartoon showcased by almost every news outlet showed President Clinton on the phone with parachutes dropping onto the White House lawn, with the speaker on the phone saying, “Mr. President, the 82nd Airborne’s here to discuss your policy on gays in the military,” and similar concerns are addressed every few years by a few people willing to inch democracy forward; though, admittedly, the implication of that cartoon on real-world events and military coups is another topic.

Throughout history, people have tried to make the All Americans the epitome of what it means to be an American, a country of black, white, yellow, brown, red; Christian, Muslim, Hindu, Jew, agnostic, atheist, spiritual, and other; with diverse bodies, beliefs, skills, and resources. We may all disagree on what it means to all be Americans, but few, if any, of us have pondered it since their grandfather was made to appear like an all-American hero by the FBI, Bobby Kennedy, and national media in the 1960’s, just to keep one person in prison.

On American soil, I’d be happy to offer my thoughs about my tattoos to anyone. Otherwise, I’m discrete, especially in Latin American countries where police, judges, and guards remembered the 1980’s and knew what was happening in Guantanamo Bay.

My record is beyond reproach. I’ve held national security clearances since 1992, when President Bill Clinton released the first part in the JFK Assassination Report, and it clearly implicated my grandfather, Ed Partin; his administration granted my diplomatic passport in 1993, and I served as an unarmed peacekeeper, a “communications liaison” for the United States as part of a 17 country coalition that reviewed my records. For 14 years, I was a Court Appointed Special Advocate for at-risk kids in the foster system, and my security clearance was overseen by nonprofit agencies protecting those kids from further harm. I have nothing to hide on American soil. In Cuba, the eco-journalist and I would be staying on the alleged guide’s family’s farm in the tobacco growing region of Vinales, the one they had said, in an email, was being remodeled into a guest house for climbers. That’s violation of Cuban law, and I told them we’d be happy with anything, that I’d be offline, and we should discuss details in person. I lean heavily towards caution when other people are involved.

I glanced at my watch; it had been less than a minute. I could still beat the happy hour crowd. Should I get another WiFi card and wait, just in case?

I was on sabbatical, I reminded myself, and could look forward to lots of diving and climbing over the next few months. I had a book to research and write. Before flying to Cuba, I had downloaded the equivalent of a library’s worth of old court reports, news articles, and records onto my phone, along with a respectable playlist of music and eight downloaded albums. I had spent all day on airplanes reading my family history and listening to a mix of New Orleans jazz and funk, ranging from Dr. John to Galactic and Trombone Shorty, and including a few bands Spotify recommended based on Cuba’s Cima Funk and The Buena Vista Social Club. Some of them spoke between sets at Tipatinas, a classic music venue in New Orleans that Galactic had bought recently, and they said Cuban Funk was where it’s at; that’s like the Pope saying he digs a young preacher’s hip sermon. I was going to finish a lot of lingering projects once free from the tether of my cell phone, and I’d listen to live music in Havana jazz clubs, not from my earbuds or iBuds or whatever they’re called.

I thought: I had a lot on my mind when I first listened to Wendy’s voice mail. I may have been distracted, and overreacted. It had been a long day. I had been sitting in cramped airplane seats and often trapped between large, chatty, and opinionated people; damn! that guy in the tight polo shirt with the pudgy belly and raccoon eyes sunburn on the leg into Fort Lauderdale wouldn’t stop talking about Disney Land, or World, or whichever one was in Florida. I may have overreacted to her voice mail. She was probably just drunk and sad about one of her dogs.

I sighed. I was tired and wanted a drink. I was Wendy’s son, and habits are hard to break.

I sighed a final time, put away my phone, straightened my back and neck, looked forward, breathed, smiled, breathed again, and tried to not limp as I strolled across the plaza and to a bar. In the back of my mind, I hoped no one would notice the obvious XXL Force Fins strapped to my backpack; I’d ditch them at the casa and switch to a daypack tomorrow.

I had read in The Lonely Planet that the diving and climbing in Cuba alone was worth the trip, even if you didn’t solve Kennedy’s murder, or deliver McDonalds breakfast sandwiches to prisoners in Guantanamo Bay. It was going to be the best sabbatical imaginable, free from people interrupting me, worries, or cares about anything other than what I cared about. That’s freedom, no matter which country you’re in. According to a professor at the University of San Diego’s Shiley-Marcos School of Engineering, being grateful for your freedom plus a bit of effort leads to success in socially responsible entrepreneurship. I believe that an abundance means you have enough to share, and I was happy that President Obama had given me an opportunity to spend 30 days in Cuba promoting entrepreneurship, whatever that means.

Wendy and I rarely discussed our Partin history. She always said that she was born WAR, but marrying my dad WARP’ed her, and that’s why she drank. I’d reply that she was a bigger part in my story than Edward Partin ever was. I didn’t want to share my small part in his story history without pointing out that pun, if only to make my mom smile.

Go to Table of Contents