Havana

But then came the killing shot that was to nail me to the cross.

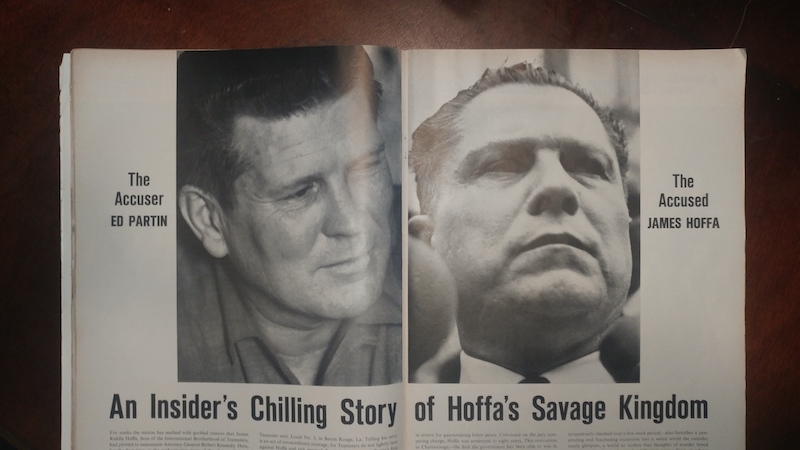

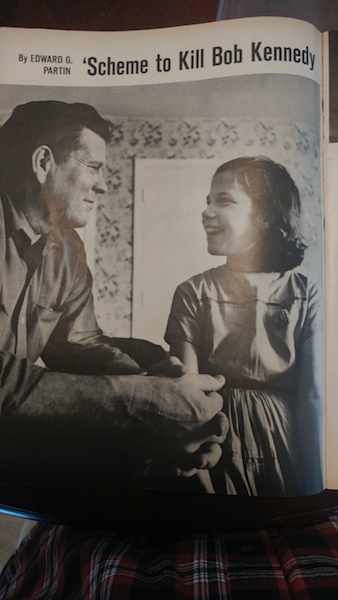

Edward Grady Partin.

And Life magazine once again was Robert Kenedy’s tool. He figured that, at long last, he was going to dust my ass and he wanted to set the public up to see what a great man he was in getting Hoffa.

Life quoted Walter Sheridan, head of the Get-Hoffa Squad, that Partin was virtually the all-American boy even though he had been in jail “because of a minor domestic problem.”1

Jimmy Hoffa, 1975

It had been a long day of flights from San Diego to Havana when the plan laid over in Houston and a thirty to thirty-five year old man plopped down next to me. I was scribbling notes in the sidelines of a book, and he asked, “What are you reading?”

I looked up slowly and flicked my pen around my thumb; depending on your age, it looked like either a magician whirling a wand to distract someone, or that scene from 1985’s Top Gun, when Val Kilmer’s hot-shot character smirked and whirled his pen in San Diego’s fighter pilot training classroom: most kids I knew began practicing it when we were bored, sitting in classrooms and listening to teachers drone on about things we didn’t care about.

I placed the pen in the crease to mark my spot and slowly closed the paperback book, leaving a bulge where the pen pushed the pages up. I was about half way though. I took off my reading glasses and removed my left earbud; it wasn’t playing anything, but I wear earbuds with noise canceling software to soften engine noise and to discourage small talk. I didn’t want him to know I could hear with earbuds in.

“Say again,” I said.

He repeated himself. I tilted the book so he could see the cover. It was “I Heard You Paint Houses: Frank ‘The Irishman’ Sheeran and Closing the Case on Jimmy Hoffa,” by Charles Brandt.

The man’s gaze skimmed across the words. He looked back up at me and cheerfully asked, “What’s it about?”

He had read the seat numbers before sitting next to me, so I assumed he was wearing contacts or didn’t need glasses. He wore a collared polo shirt t that was too tight and emphasized a bulbous belly that had likely grown since he bought the shirt; I assumed he chose it either mindlessly or to emphasize his arms, which had hints of muscle tone lurking beneath a few extra pounds, as if he had played some sport in college before getting an office job. His face was slightly tanned, and he had subtle raccoon-eyes that exposed pale white skin. I imagined he wore expensive sunglasses and bright colored polo shirts when golfing with coworkers on weekends.

His smell was unremarkable. He had a clean shaven face but no hint of aftershave, and I sensed neither soap nor body odor. He was young and educated enough to not smoke or spend time around people who did. Educated or not, to me he was still a kid. In the book I was reading when the he interrupted me, I had just read Frank The Irishman’s saying, in his harsh New Jersey hitman voice: “Kids nowadays don’t know who Hoffa was. I mean, they may know the name, but they don’t know how much power he had.”

I forced a thin smile and rotated the book so the kid could see the back cover with the description and accolades. He glanced down and looked up a fraction of a second later, and said, “Did you go to LSU?”

I said, “I’m not sure why you ask.”

He nodded towards my head and said, “Because your hat says LSU.”

You couldn’t get anything by this kid. I had chosen an old LSU wool baseball cap that was so faded you could barely make out the letters. Instead of purple and gold, the hat was more of a weak brown with a sunburnt yellow L, S, and U. I wore it on the flight to shield my thinning hair and relatively new bald spot from overhead air conditioners that seem to target my head like campfire smoke seeks my eyes. I could have worn any hat, but at that time the faded LSU cap was my favorite out of about a dozen hats, including three LSU baseball caps. I don’t think I’m superstitious, but some things in my life had been aligning so perfectly that I chose the hat to keep me paying attention.

I first saw the hat floating in the ocean off Point Loma the previous May, bobbing in waves almost a football field length from the surf break below remote cliffs at the edge of Point Loma Lazerene University, just after I told myself I needed a hat to shade my sizzling scalp. It had been an epic surf morning that I wanted to last forever, but my sunscreen was waning and the noontime sun shot rays through cloudless Santa Anna skies directly onto my newly noticed San Diego Friars hair style (our baseball team’s mascot has a hilarious bald spot). I paddled over to retrieve it. I was already respecting the coincidence, and I laughed out loud when I saw that it said LSU.

I sat upright on my board, so far past the breaks that I was bobbing only slightly. I shook the hat to fling out salt water and any seaweed or crabs may have been inside, and inspected the inner rim. It was a licensed size 7-1/4, a tad bit smaller than my 7-3/8th head. I smiled and thought to myself that beggars shouldn’t be choosers. I donned it and resumed surfing. As I had hoped, the day continued to be one of the best surf days I had experienced in almost twenty years of surfing San Diego, and with my bald spot covered and nose mostly shaded, that’s what dominated my mind.

I was less surprised to find an LSU hat than you’d imagine. I was surfing a month after the 2018 San Diego LSU Alumni association crawfish boil, the largest crawfish boil outside of Louisiana. It has around 36,000 attendees and is held in the outdoor Qualcomm Stadium, and many attendees wear hats for shade and to show their allegiances. (Many SEC hats are there, though our regional rivalries are set aside and the SEC is unified among legions of Californians.) To feed that many people crawfish, a fleet of 18 wheelers – probably piloted by Teamsters – trucked the mudbugs from Lafayette, also enough for the annual San Diego Gator By The Bay festival held the following two weekends, and any one of the truck drivers or attendees at either event could have dropped the hat overboard on a fishing trip to the kelp beds near Pint Loma, or lost it from a beach along any one of our 78 miles of coastline. It made sense, and I was less surprised to see an LSU hat than I had been to see any hat bobbing beside me when I needed one. That it was an LSU hat was just a bit of lagniappe that made the day more remarkable.

I was born in Baton Rouge in 1972, and though I moved almost every year, I was always within dozen miles of LSU’s campus. I was in Baton Rouge around the time of Skip Bertman’s reign over LSU baseball, when we won six of ten College World Series (rivaling California’s Stanford, who won the other four); Shaquelle Oneal’s time as a basketball star before he left for the newly formed Orlando Magic pro team in 1992 (he’d return to LSU to complete his degree as a multi-millionaire pro basketball player); and the world-record setting 1988 50-yard touchdown throw in sudden-death overtime against Auburn in LSU’s Death Valley stadium, when almost 88,000 fans jumped celebrated by jumping up and down to the Tiger marching band beat and created the world’s only recorded man-made earthquake, a 3.8 on the Richter scale (we’re in the Guinness Book of World Records for that).

I left Baton Rouge for the army in 1990, but returned in 1994 and was voted co-captain of the renewed LSU wrestling program. I was mentored by the legendary 1970’s wrestling coach who was recruited from Iowa to build the team in 1969 and skyrocketed LSU to fourth in the nation, Coach Dale Ketelsen. Despite their success, the team was disbanded in 1979, along with about 100 other college teams nationally, in response to the Title IX law that required equal numbers of women in college sports as men; but Coach remained in Baton Rouge so that his kids could graduate with their friends, and in the 1980’s began a program at Belaire High School, where I met him in 1986, when I was a 126 pound sophomore and just learning how to spin a pen around my finger. Ten years later, when I was a 23 year old combat veteran and co-captain of LSU’s reinvigorated wrestling program, we hosted the first college wrestling match in Louisiana since LSU’s team was disbanded. Our historic match filled the newly built sports complex and was attended by Coach and his wife and adult children; practically every high school wresting coach in Baton Rouge; several LSU cheerleaders; and a bleacher section full of young ladies from the nearby Gold Club who had worked all night but still showed up that morning, because they thought we looked good in the tight purple singlets Coach had magically produced for us.

I left Baton Rouge for the final time when I graduated from LSU in May of 1997 with a summa cum laude degree in civil and environmental engineering – one of only eleven environmental engineering programs in America back then – and after a brief stent in graduate school for biomedical engineering, I married Cristi, a young lady from Los Angeles I had met when she was a medic at Fort Bragg’s hospital and had bandaged me up more than a few times, and we settled in San Diego because of its beaches and burgeoning biotechnology industry. Almost twenty years later, I led engineering classes and a hands-on innovation center at The University of San Diego’s Shiley-Marcos School of Engineering and the newly formed cyber-security program. I took a three month sabatical every spring to coincide with Louisiana’s crawfish season and my favorite music festivals, and I sometimes flew home in fall for LSU football games in Tiger Stadium, which we all call Death Valley; it’s been expanded since the 1988 earthquake victory, and is the nation’s 5th largest stadium, holding around 90,000 fans inside and another 30,000 tailgaters in the parking lot. My personal email among old friends since google launched gmail in 2004 was LSUmagic@gmail.com, and my former high school wrestling team and LSU team sometimes organized reunions timed with Louisiana wresting state tournaments and the Louisiana master’s wrestling tournament for old coaches and aging athletes.

I told the young man, “I grew up in Baton Rouge.”

He asked if I lived in Houston now.

In fairness, Louisiana’s agriculture and tourism based economy meant that a lot of LSU graduates move to either Houston or Atlanta for office jobs. There are so many LSU graduates in Houston that it hosts the second largest crawfish boil outside of Louisiana every spring, and Houston golf courses are packed with people wearing LSU hats. I’m sure he was just being friendly in his own way. But, I suspected that no matter what I answered, he’d begin asking where I lived, where I was going, what I did for a living, or something about my family, so I said I was focused on reading and didn’t want to talk.

He shrugged, adjusted the overhead air away from him and inadvertently towards my head. He pulled out his smart phone and busied himself by scrolling Facebook. I put the earbud back in and returned to reading and scribbling notes. The plane took off, and he paid the WiFi upcharge and scrolled through his phone the rest of the flight without interrupting me again.

It was Friday afternoon, 01 March 2019. I was on my first day of a three-month sabbatical with 30 days in Cuba to research my grandfather’s role in President Kennedy’s assassination. He was Edward Grady Partin Senior, the Baton Rouge Teamster leader famous in the 1960’s and 70’s for infiltrating Jimmy Hoffa’s inner circle and sending him to prison for eight years; that trial was ten months after President Kennedy’s assassination, and the president’s little brother, US Attorney General Bobby Kennedy, had personally overseen my grandfather’s release from jail and infiltration into Hoffa’s camp. For a while, my family was famous as “America’s first family of paid informants,” and my grandfather was portrayed in 1983’s Blood Feud about the battle between Bobby and Hoffa by the famous actor – at that time – Brian Dennehy, who had just stared in Rambo: First Blood and a few other classic films in the early 80’s. Robert Black won an academy award for “channeling Hoffa’s Rage,” and a daytime soap opera heart throb whose name I can’t recall portrayed Bobby Kennedy; that was when all of America knew the story and actors needed to look like the people they portrayed; Brian was a handsome, rugged actor who looked somewhat like my grandfather, whom we called Big Daddy, but was noticeably smaller and less brutal than you’d imagine a Teamster leader to be back then. We called my grandfather Big Daddy, and he passed away on 11 March 1990, two weeks after my final high school wrestling match in the Baton Rouge City Finals and shortly before I left Louisiana to join the 82nd Airborne, America’s quick reactionary force that left North Carolina on two hours notice and arrived in Saudi Arabia 18 hours later to, as President Bush Sr. said, “draw a line in the sand” and stand against the world’s largest tank force and about 450,000 Iraqi soldiers, beginning Desert Shield and leading to Desert Storm.

I’m Jason Ian Partin. My father is Edward Grady Partin Junior, Big Daddy’s second oldest child and his oldest son; my mother had the grace and foresight to not name me Edward Grady Partin III.My middle name is from the singer for Jethro Tull, Ian Anderson, pronounced with an “e” sound, e-an; and my first name is from a trend in the 70’s best summarized by a late 70’s parenting book called “What to name your child other than Jason or Jennifer.” There were so many Jason’s in my high school classes that everyone at Belaire called me by my nickname, Magic. (The nickname began my 9th grade year, when I spent one year at Baton Rouge’s Scotlandville Magnet High School for the Engineering Professions, which didn’t have a sports program; at the time, David Copperfield’s annual magic specials were the rage and the nickname stuck.) Since my grandfather’s funeral, when I met Walter Sheridan, the former presidenttial campaign manager for John F. Kennedy and Bobby Kennedy and FBI agent who led Bobby and J. Edgar Hoover’s “Get Hoffa” task force of about 30 agents for ten years, I’ve had an on-and-off hobby of researching his role in conspiracies beyond the Jimmy Hoffa’s conviction in 1964 and disappearance in 1975. I use time on flights to read that latest books and conspiracy theories without the distractions of daily life. Like LSU revamped their wrestling team, I had restarted my research into Big Daddy’s role in Kennedy’s assassination on the coincidental March anniversary of his death. I narrowed the search to Cuba. My mind had been swarming with memories the entire flight, and I wanted to keep reading without interruption.

I finished reading The Irishman somewhere over the Gulf of Mexico. There wasn’t much to look at out our right hand side of the plane other than clouds and an occasional glimpse of the ocean, so I reread my scribbles. The plane crossed over the Florida panhandle, and I put the book away and watched patches of ground peek between clouds, and let what I read digest and link with what I read in other books over the decades and stories I overheard when I was a kid. We landed in Fort Lauderdale an hour later. My row stood up and gathered our baggage from the overhead bins. When the airplane doors finally opened, the man beside me moved forward and looked over his shoulder and cheerfully said, “have a nice vacation.” I nodded and said, “You, too.”

I hadn’t checked anything, so I carried my small personal items backpack and rolled up yoga mat, and wore a larger carryon backpack with a pair of squat scuba fins strapped in the outside flap. I left the airliner and walked through the Fort Lauderdale terminal to a smaller plane bound for Havana. About an hour and a half later, I stepped off the plane and on onto the tarmac in Havana, finally in Cuba after almost 25 years of thinking about it.

Go to The Table of Contents

Footnotes:

- The “minor domestic problem” was a reoccurring point in Hoffa’s defense strategy after my grandfather testified against him in 1964, ten months after President Kennedy was assassinated and his little brother, U.S. Attorney General Bobby Kennedy, believed that Hoffa had led the assassination. President Kennedy, when a senator on the U.S. labor relations committee, had spearheaded the crusade against the Teamsters and focused on Jimmy Hoffa; after becoming president, he appointed Bobby, a fresh Harvard law school graduate, as the Attorney General with two things to focus on: stopping the newly acknowledged menace of organized crime in America, and putting Jimmy Hoffa in jail. In 1962, Bobby freed Big Daddy from a Baton Rouge jail and expunged most of his extensive criminal records across America in exchange for finding “anything” to convict Hoffa; the opportunity came in a minor state-level anti-trust trial against Hoffa’s Test Fleet, a trucking company Hoffa created in 1949 to lease trucks to companies agreeing to use Teamster labor for shipping, when Big Daddy secretly reported that Hoffa tried to get him to bribe jurors. Hoffa was found not guilty in the Test Fleet case, but he was charged with the much more severe federal charge of jury-tampering and went to trial for that in 1964. When Big Daddy stood up as the surprise witness, Hoffa exclaimed, “My God, it’s Partin!” and, according to his closest allies in court, Hoffa “went white as a ghost” and immediately asked his army of high-end attorneys to begin “digging up dirt” on Big Daddy. Simultaneously, Bobby tasked his FBI “Get Hoffa” team of dozen to hundreds of agents led by Walter Sheridan, a respected agent and former campaign manager for John F. Kennedy, to purge Big Daddy’s records; Bobby then asked his friend and editor of Life magazine, the most widely read and probably most respected media in America back then, to profile Big Daddy as an all-American hero and to showcase my family with him so readers would empathize with the family-man who risked his life to stop Teamster corruption and probably save Bobby Kennedy’s life based on a 1962 report overseen by FBI director J. Edgar Hoover that said Jimmy Hoffa was plotting to kill Bobby Kennedy using plastic explosives he had asked Big Daddy to obtain from New Orleans mafia boss Carlos Marcello. Hoffa fought his conviction all the way to the supreme court while Big Daddy was celebrated nationally, loosing his appeals and being sentenced to eight years in federal prison based on Big Daddy’s word.

For the next 13 years of his life Hoffa, quoted Life magazine calling Big Daddy an all-American hero using “rabbit ears” to emphasize his sarcasme about my grandfather’s “minor domestic problem.” In Hoffa’s second co-writen autobiography, “Hoffa: The Real Story,” published by Stein and Day about a month before he vanished in 1975, Hoffa had this to say about my grandfather and his testimony:

Let’s take a look at this “all-American boy” and his record, which was carefully kept from the jury by Judge Wilson and the government.

In December, 1943, he was arrested in the state of Washington for breaking and entering. Pleading guildy, he was senteneded to fifteen years in the state penitentiary, from which he escaped twice.

Freed, he joined the Marine Corps and was dishonorably discharged. He had been accused of raping a young black girl.

Becoming head of the Teamster local in Baton Rouge, he was charged by certain members with embezzling $1600 in union funds and he had been indicted on thirteen counts of falsifying records and thirteen counts of embezzlement.

While out on fifty thougsand dollars’ bond, he had been indicted in Alamama in Septermber of 1962 on charges of first-degree manslaughter and leaving the scene of an accident.

One day beofe the Alambama incictment, he surrendered on September 25th, 1962, to Louisiana authorities on a kidnaping charge, the “minor domestic problem” to which Life magazine had referred. He had assisted a friend in snatching the friend’s two small children from the friend’s wife, who had leagal custody of the children.”

Walter Sheridan, who spent a decade heading the FBI’s Get Hoffa Task Force under Bobby Kennedy and John F. Kennedy before that, couldn’t deny the facts presented by Hoffa. In his 1972 Opus, “The Fall and Rise of Jimmy Hoffa,” published by Saturday Evening Press, Walter addressed the growing public realization that the star witness against Hoffa was controversial by admitting:

“Partin, like Hoffa, had come up the hard way. While Hoffa was building his power base in Detroit during the early forties, Partin was drifting around the country getting in and out of trouble with the law. When he was seventeen he received a bad conduct discharge from the Marine Corps in the state of Washington for stealing a watch.One month later he was charged in Roseburg, Oregon, for car theft. The case was dismissed with the stipulation that Partin return to his home in Natchez, Mississippi. Two years later Partin was back on the West Coast where he pleaded guilty to second degree burglary. He served three yeas in the Washington State Reformatory and was parolled in February, 1947. One year later, back in Mississippi, Partin was again in trouble and served ninety days on a plea to a charge of petit larceny. Then he decided to settle down. He joined the Teamsters Union, went to work, and married a quiet, attractive Baton Rouge girl. In 1952 he was elected to the top post in Local 5 in Baton Rouge. When Hoffa pushed his sphere of influence into Louisiana, Partin joined forces and helped to forcibly install Hoffa’s man, Chuck Winters from Chicago, as the head of the Teamsters in New Orleans.

Small discrepancies between Walter and Hoffa’s summaries are part of my family’s stories. For example, Big Daddy didn’t join the marines out of patriotism or a desire to stop Nazi Germany – it was a plea bargain to keep him from going to jail. He and his little brother, my uncle Doug, had been arrested for stealing all the guns in Woodville, Mississippi, and selling most of them to hitmen two hours downriver in New Orleans. They were found guilty, but Doug was released because he was only 12. The judge told Big Daddy to join the marines and fight in WWII (it was 1943) or go to jail. My then 17 year old grandfather noticed a nuance in the phrasing, and agreed to join the marines knowing he’d do something to get kicked out. Two weeks after enlisting, he punched out his commanding officer and stole a watch from the unconscious captain’s arm. The discrepancy about the watch was probably due to the Marine captain reporting his watch stolen rather than admitting he was punched out by a 17 year old recruit.

Big Daddy returned to Woodville having outsmarted the judge and feeling immune to prosecution. He took over the sawmill union, and soon after was arrested for raping a young Woodville girl. He was found not guilty by the local jury of his peers. Woodville was, and is, a small town, and everyone knew Big Daddy, and I can’t imagine a local jury voting to put him in jail. According to Doug’s 2017 autobiography almost 70 years later (“From my Brother’s Shadow: Teamster Douglas Wesley Partin Tells His Side of the Story,” self-published from a Mississippi veterans nursing home and not edited), my grandfather was found not guilty of raping the girl because one juror said, “No white man deserves to go to jail for anything he did to a black girl.” This was in the highly segregated south, twenty years before Mississippi governor George Wallace would order the national guard to stop a young African American girl from attending her first day at Mississippi State University; and, of course, the famous marches like in Selma and the assassination of Martin Luther King Junior on 04 April 1968, so it’s not surprising that in the late 1940’s our alleged blind justice system would allow Big Daddy to go free by a generation who had ostensibly fought the prejudices of Nazi Germany.

Soon after being found not guilty of raping a black girl (that adjective was used for decades), Big Daddy took over the truckers union that delivered trees to the sawmill and carried away cut lumber, getting paid three times: the union contracts to deliver trees, cut them, and carry away lumber. These are some of the tactics that brought awareness of Big Daddy to the International Brotherhood of Teamsters and led him to being trusted by Jimmy Hoffa. In the big picture, rather than analyze each detail, it’s safe to assume that Big Daddy wasn’t an all-American hero to everyone.

As early as 1966, Chief Justice Earl Warren tried to dispel that myth that Big Daddy was an all-American hero when he delved into facts to support his decision in Hoffa vs The United States.Warren was already famous for cases such as Roe vs Wade, Brown vs The Board of Education, the case that gave us the Miranda Rights, and, of course, the 1964 Warren Report hastily assembled and mistakenly claiming that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone when he shot and killed President John F. Kennedy, and that Jack Ruby acted alone when he shot and killed Oswald two days later. Like Hoffa’s 1964 trial, Hoffa vs The United States was followed by practically every American, and most people were surprised when Warren was the only judge to dissent against Big Daddy’s testimony, which ended Hoffa’s appeals and began his prison sentence. Warren wrote a multi-page missive railing against Big Daddy, permanently attached to Hoffa vs The United States for posterity to ponder, and here’s a part of it:

Here, Edward Partin, a jailbird languishing in a Louisiana jail under indictments for such state and federal crimes as embezzlement, kidnapping, and manslaughter (and soon to be charged with perjury and assault), contacted federal authorities and told them he was willing to become, and would be useful as, an informer against Hoffa, who was then about to be tried in the Test Fleet case. A motive for his doing this is immediately apparent — namely, his strong desire to work his way out of jail and out of his various legal entanglements with the State and Federal Governments. And it is interesting to note that, if this was his motive, he has been uniquely successful in satisfying it. In the four years since he first volunteered to be an informer against Hoffa he has not been prosecuted on any of the serious federal charges for which he was at that time jailed, and the state charges have apparently vanished into thin air.

This type of informer and the uses to which he was put in this case evidence a serious potential for undermining the integrity of the truthfinding process in the federal courts. Given the incentives and background of Partin, no conviction should be allowed to stand when based heavily on his testimony. And that is exactly the quicksand upon which these convictions rest, because, without Partin, who was the principal government witness, there would probably have been no convictions here.

Here, the Government reaches into the jailhouse to employ a man who was himself facing indictments far more serious (and later including one for perjury) than the one confronting the man against whom he offered to inform. It employed him not for the purpose of testifying to something that had already happened, but rather for the purpose of infiltration to see if crimes would in the future be committed. The Government, in its zeal, even assisted him in gaining a position from which he could be a witness to the confidential relationship of attorney and client engaged in the preparation of a criminal defense. And, for the dubious evidence thus obtained, the Government paid an enormous price.

In 1966, after loosing appeals all the way to the US supreme court, Jimmy Hoffa was sentenced to eight years in prison based, according to Chief Justice Earl Warren, almost exclusively on my grandfather’s word of honor, a man so close to Hoffa that he had trusted his life to him. To say Hoffa was pissed off is probably an understatement. He went to prison in 1966, and had a long time to ruminate about the “all-American hero” who put him there. To this day, parts of the congressional JFK and Martin Luther King Jr. Assassination Report remain classified, and Big Daddy’s records continue to “vanish into thin air.” I can’t imagine what Hoffa would have to say about that, but I’m sure it would be interesting to read, full of sarcasm about “blind justice” and with biblical allusions about accepting pieces of silver to nail someone to a cross.

It’s worth noting that Hoffa did, in fact, orchestrate bribing jurors on many occasions, including the Test Fleet case; this has been confirmed by dozens of books including those by Hoffa’s army of attorneys and the inner-circle who sat next to Hofa when Big Daddy stood up. Yet that didn’t assuage his anger, nor does it change his views about showcasing Big Daddy as an “all-American hero” and Bobby using his connections to influence media and therefore each and every American who, at the very least, is owed truthful information by their government. ↩︎