Havana, 01 March 2019

But then came the killing shot that was to nail me to the cross.

Edward Grady Partin.

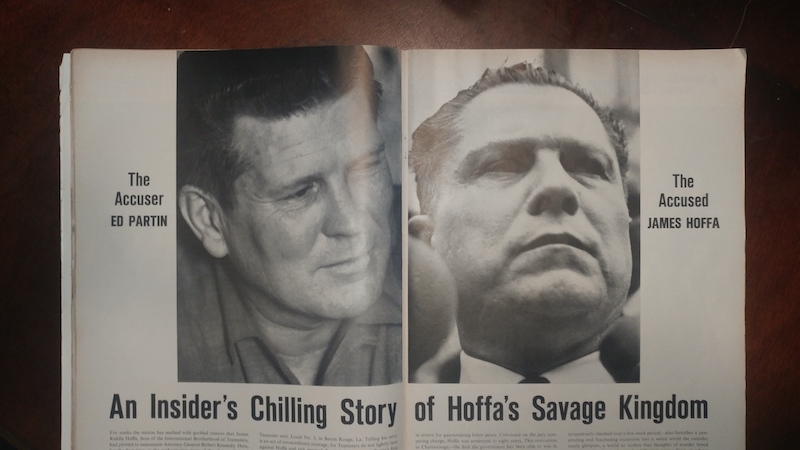

And Life magazine once again was Robert Kenedy’s tool. He figured that, at long last, he was going to dust my ass and he wanted to set the public up to see what a great man he was in getting Hoffa.

Life quoted Walter Sheridan, head of the Get-Hoffa Squad, that Partin was virtually the all-American boy even though he had been in jail “because of a minor domestic problem.”1

Jimmy Hoffa, 1975

It was a long day of flights from San Diego to Havana. The plane laid over in Houston for an hour, and I was scribbling notes in the sidelines of a book when a man boarded and plopped into the seat beside me.

“What are you reading?” he asked.

I looked up slowly and flicked my pen around my right thumb, like a magician whirling a wand to distract someone. I placed it on the page I was reading and closed the paperback. I took off my reading glasses and removed my left earbud; it wasn’t playing anything, but I wear earbuds with noise canceling software to soften engine noise and to discourage small talk. I didn’t want him to know I could hear with earbuds in.

“Say again,” I said.

He repeated himself. I tilted the book so he could see the cover. It was “I Heard You Paint Houses: Frank ‘The Irishman’ Sheeran and Closing the Case on Jimmy Hoffa,” by Charles Brandt. The man’s gaze skimmed across the words.

He looked back up at me and cheerfully asked, “What’s it about?”

He had read the seat numbers before sitting down, so I assumed he didn’t need glasses. He was a nondescript 35-or-so year old with a polo shirt that was too tight and emphasized a bulbous belly that had likely grown since he bought the shirt; I assumed he chose it either mindlessly or to emphasize his arms, which had hints of muscle tone lurking beneath a few extra pounds, as if he had played some sport in college before getting an office job. His face was slightly tanned, and he had subtle raccoon-eyes that exposed pale white skin. I imagined he wore expensive sunglasses and bright colored polo shirts when golfing with coworkers on weekends. It’s possible he didn’t know who Jimmy Hoffa was; in the book, I had just read Frank The Irishman’s harsh New Jersey hitman voice saying, “kids nowadays don’t know who Hoffa was. I mean, they may know the name, but they don’t know how much power he had.”

I forced a thin smile and rotated the book to show the back cover. He glanced down.

He looked back up and said, “Did you go to LSU?”

“I’m not sure why you ask,” I said.

He nodded towards my head and said, “Because your hat says LSU.”

You couldn’t get anything by this guy. I had chosen an older, wool baseball cap for the cooler months that was so faded you could barely make out the letters; instead of purple and gold, the hat was more of a weak brown with a sunburnt yellow L, S, and U. I wore it to shield my thinning hair and relatively new bald spot from overhead air conditioners that seem to target my head like campfire smoke seeks my eyes.

I first saw the hat floating in the ocean off Point Loma the previous May, bobbing in waves almost a football field length from the surf break below Point Loma Lazerene University, just after I told myself I needed a hat to shade my burning scalp. I paddled over to retrieve it, and laughed out loud when I saw that it said LSU. It was a size 7-1/4, a tad bit smaller than my 7-3/8th head, but beggars shouldn’t be choosers. I was surfing a month after the 2018 San Diego LSU Alumni association crawfish boil, the largest crawfish boil outside of Louisiana, with around 36,000 attendees. To feed that many people crawfish, a fleet of 18 wheelers trucked the mudbugs from Lafayette, also enough for the annual San Diego Gator By The Bay festival, and any one of the truck drivers or attendees could have dropped the hat overboard on a fishing trip to the kelp beds near Pint Loma, or lost it from a beach along any one of our 78 miles of coastline.

Any hat would have allowed me to keep surfing, but to see an LSU hat bob beside me made the day much more remarkable. I was born in Baton Rouge in 1972, and though I moved almost every year, I was always within dozen miles of LSU’s campus. I was in Baton Rouge around the time of Skip Bertman’s reign over LSU baseball, when they won six of ten College World Series (rivaling California’s Stanford, who won the other four); Shaquelle Oneal’s time as a basketball star before he left for the newly formed Orlando Magic pro team in 1992; and the world-record setting 1988 50-yard touchdown throw in sudden-death overtime against Auburn in Death Valley, when almost 88,000 fans jumped celebrated by jumping up and down to the Tiger marching band beat and created the world’s only recorded man-made earthquake, a 3.8 on the Richter scale. I left for the army in 1990, but returned in 1994 and was voted co-captain of the renewed Tiger wrestling program, and was mentored by the 1970’s LSU wrestling coach who had skyrocketed LSU to fourth in the nation, Coach Dale Ketelsen, In 1996, LSU’s newfound program hosted the first college wrestling match in Louisiana since LSU’s team was disbanded in 1979, after the Title IX law enforced equal numbers of male and female athletes in collegiate sports. Our historic match filled the Pete Marovich assembly center and was attended by Coach and his wife and adult children, practically every high school wresting coach in Baton Rouge, several LSU cheerleaders, and a bleacher section full of young ladies from the nearby Gold Club who thought we looked good in tight purple singlets.

I left Baton Rouge for the final time when I graduated from LSU in May of 1997 with degree in civil and environmental engineering – one of only eleven environmental engineering programs in America back then – and soon settled in San Diego. With every move, I carried a small cardboard box with my degree and a handful of awards from campus organizations, and I sometimes flew home for crawfish season, music festivals, and – of course – LSU football games in the Death Valley, Since Google launched gmail in 2004, my address has been LSUmagic@gmail.com. To say I love LSU is an understatement.

I said, “I grew up in Baton Rouge.”

He asked if I lived in Houston now.

In fairness, Louisiana’s agriculture and tourism based economy meant that a lot of LSU graduates move to either Houston or Atlanta for office jobs. There are so many LSU graduates in Houston that it hosts the second largest crawfish boil outside of Louisiana every spring, and Houston golf courses are packed with people wearing LSU hats. I’m sure he was just being friendly in his own way. But, I suspected that no matter what I answered, he’d begin asking where I lived, where I was going, or what I did for a living; or, even worse, he’d ask about my family.

I said I was focused on reading and didn’t want to talk.

He shrugged, pulled out his smart phone, and busied himself by scrolling Facebook. I put the earbud back in and returned to reading and scribbling notes. The plane took off, and he paid the WiFi upcharge and scrolled through his phone the rest of the flight without interrupting me.

It was Friday afternoon, 01 March 2019. I was on my first day of a 30 day sabbatical to research my grandfather’s role in President Kennedy’s assassination on another Friday afternoon, 22 November 1963. I was using an entrepreneurship visa granted by the Obama administration to enter Cuba, which had been under an American embargo since Kennedy enacted it in 1961, just before the Bay of Pigs invasion. Trump’s administration was about to eliminate the entrepreneurship loophole, and I was lucky to be one of the few who took advantage of the opportunity. But I’m slightly claustrophobic, and have been since 1983. I know the symptoms. Sitting in small spaces all day had led to my mind being agitated, my head hurting, and my body screaming louder than the jet engines. My mind craved jumping out of the plane and into the silence of a wide open sky, if only for a few minutes of peace. To stay calm, I read and kept opinions to myself.

I finished reading The Irishman somewhere over the Gulf of Mexico. There wasn’t much to look at out our right hand side of the plane other than clouds and an occasional glimpse of the ocean, so I reread my notes and allowed the information to settle deep into my memories. As a freshman at LSU in 1994, I stumbled across a Harvard research study that compared memory retention for three groups given the same class and a test three weeks later: one group did not review notes, one reviewed just after taking them but not again, and one reviewed them just before the test. By far, the students who reviewed notes immediately after performed better on tests. A mentor when I was in high school, a math teacher and voracious reader, had intuitively known how memories form, and gave me books to write in rather than static books read but not retained and turned in for the next year’s students.

As a kid, before I realized the power of scribbling, I studied books by the magician and memory expert Harry Lorayne, and attended his lectures at monthly meetings of the Baton Rouge International Brotherhood of Magicians Ring #178, the Pike Burden Honorary Ring, held the third Tuesday of every month at a synagogue of one of the members, Martin Samules, a retired chemical engineering manager at DuPont known to his congregation as “The Magical Mishigas.” Harry’s methods never worked for me, but scribbling did. Ironically, I can’t recall the name of the Harvard study or the journal in which it was published (it’s easily found online), but I’ve used the lessons from it for more than 25 years. If memory is a skill, it takes practice to stay sharp, the same way a knife must be honed to remain effective.

The plane crossed over the Florida panhandle. I put the book away and watched patches of ground peek between clouds and let what I read digest. The plane landed in Fort Lauderdale an hour later. My row stood up and gathered our baggage from the overhead bins. When the airplane doors finally opened, the man beside me moved forward and looked over his shoulder and cheerfully said, “have a nice vacation.” I imagined he had golf clubs waiting in checked bags, and was meeting coworkers in Fort Lauderdale. I nodded and said, “You, too.”

I hadn’t checked anything, so I wore my carryon backpack with a pair of squat scuba fins strapped in the outside flap, and I hand-carried my rolled up yoga mat. I walked through the terminal to smaller plane.

I didn’t know what I’d do when we landed. The flight was part of a new service to Havana in wake of Obama’s relaxing the embargo for Americans, and the ticket came with 30 days of travel health insurance that included extraction back to the states, per Cuba’s requirements to protect their state-funded healthcare system from paying for uninsured tourists. Attendants confirmed my ticket and visa, and I took my seat. The elderly Cuban gentleman who sat next to me and took off his bandera and rested it on his knee, smiled and nodded, and simply said “buenas tardes,” that blissfully polite Spanish phrase that needs no forced reply. I smiled back and wished him a good flight. I put in my earbuds, pulled out the Lonely Planet, and began underlining casa particulares and making notes bout the streets and neighborhoods of Havana. About an hour and a half later, I stepped off the plane and on onto the tarmac in Havana.

I took a deep breath and inadvertently inhaled a lung full of JP-4 jetfuel. Despite the sudden urge to vomit, I exhaled with a content sigh and smiled. Any day you land with the plane is a good day.

Suddenly, I whipped my head around and looked up the plane’s stairs to the exit door.

“Fuck!” I exclaimed so loudly that you could have heard it over the engine’s roar. I had left my yoga mat in the overhead bin.

People were still disembarking, but it was too late to go back. Cuban officials were directing me towards customs. I took kanother deep breath of JP-4, and reminded myself that I had planned on shopping, anyway, to see what was on the shelves on a communist island and to keep an eye out for entrepreneurs sprouting between the cracks of Havana sidewalks. Tomorrow, I could buy another mat, or something that would suffice, like a thick towel. I had once read that every traveler should always carry a towel, and maybe they were right.

I exhaled and snapped my head back and forth to loosen neck muscles, tightened my hip belt, and followed the official’s finger across the tarmac towards a sign for customs. I walked slowly and forced my stiff hips to move as smoothly as possible.

As I walked, I reflected on why I had forgotten the yoga mat. I’ve left things here and there as long as I can remember, so I viewed water bottles, jackets, pens, and other things I set down mindlessly as disposable. But I only had two things to grab from the plane, and I wanted to use the mat after a long day of sitting. I was worried. During the previous year’s sabattical, I realized that my memory may be failing. I was converting US dollars to Nepali rupees, and couldn’t complete simple math. Six times seven is 42, the answer to Life, The Universe, and Everything; a number I should have known from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, the book that suggests always carrying a towel. Yet it alluded my mimd for almost two minutes, the length of a round of wrestling; a lifetime in my mind. And the number 42 was in the news in 2018, because Elon Musk launched his red Tesla convertible into space atop a Space-X rocket; he was a fam of Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, and had pasted the car with “Don’t Panic” bumper stickers and other references that reinvigorated internet memes about the book and answer to Life, The Universe, and Everything. 42 was also the Ranger Pat Tillman’s jersey number when he played for the Arizona Cardinals, before he quit football and joined the army and was shot and killed in Afghanistan. Two minutes was a long time to not see the answer to six times seven, and when I finally did I began paying more attention to my mind. I saw more lapses I would have otherwise never noticed.

Two months later, I returned to San Diego and told my primary physician at the VA hospital what I had noticed. I was only 46 years old, but he was alarmed and said that I may be showing early symptoms of a neurological disorder akin to Alzheimers or Parkinsons. He thought it could be related to what the VA called Desert Storm Syndrome, and the VA began monitoring my memory. I had VA medical records and psychological exams for security clearances dating back to 1990, but they never tested my memory. In 2018, I passed all preliminary exams – they were simple memorization tests designed for gross losses – but I remained mindful of the possibility of gradual and almost imperceivable memory degradation. Neural links break bit by bit, so slowly that moat people son’t notice. In Baton Rouge, a lesson is taught by the parable of how to boil a frog: slowly, and start with room temperature water. A frog will jump out of a boiling pot, but id it’s comfortable it won’t notice the temperature rising and will drift off to sleep and never wake up. (The parable often ends with a recipe for frog leg sauce picante.) I knew older friends and mentors who entered dementia so slowly that not only did they not notice, neither did anyone else. We assumed that their increasing grumpiness and forgetfulness was just getting older. Coach was one of them; his 2015 passing was still fresh in my mind.2

After my preliminary diagnosis, I began trying to pay attention to my memory and mood throughout each day. I also dusted off Harry Lorayne’s books and began exercising my mind, hoping to avert or at least slow down any possible decline. The mind needs exercise, just like the body. I began writing a memoir, verifying childhood memories with news events and court records available online, just like my 88 year old great-uncle Doug Partin had recently done from his Mississippi Veterans convalescent home for similar reasons. At the least, I hoped to become more aware of lapses, and to avoid becoming confused and irritable around people; and to avoid what had happened to Robin Williams and probably to Ernest Hemmingway, both of whom died with neurological damage that makes the cause ambiguous. At the higher end of hope, I wanted to avert the crisis and live another 30 pr 40 years with my mind alert and memories intact. A three month sabbatical would allow uninterrupted time to write and exercise my mind and body and see how things progressed.

I paused before entering the building and sighed again, though not contently this time. Since Nepal, I ruminated about every memory lapse, no matter how seemingly insignificant. I’ve been claustrophobic since 1983, so I know that being in any confined space more than about 20 minutes makes me feel agitated, act grumpily, and make mistakes; I decided that forgetting the mat was nothing more than a consequence of being cooped up all day. No matter the reason, there was nothing to do about the mat at that moment, so I entered the building and strolled up to two customs officials sitting at a simple folding table.

The officials stopped joking with each other to greet me. I took off my backpack, pulled out a money belt from the front of my pants, and handed them my passport and round-trip plane ticket. I smiled. They smiled back with what could only be genuine friendliness.

The older and presumably senior official checked my travel insurance and return flight more thoroughly than my visa. I was on the first day of a three month sabattical, and had a 30 day visa for Cuba. My flight back was on March 28th to provide a safety window for delayed flights or anything unexpected. I wondered if they would comment on the uniqueness of my visa, but the senior official was more interested in the Force Fins strapped to my backpack. He ran his finger along the thick polypropolene and flicked one of the tips with a curious countenance.

Force Fins are different than most SCUBA fins. They’re thick, short, black, duck-feet-looking fins modeled after a dolphin’s tail, invented by a guy in the 1980’s whose name I can never recall and used by SEALS and Rangers in the 80’s and 90’s for long-distance underwater missions. The patents had long since expired (back then, patents expired 20 years after issue, now they become public domain 17 years after filing). But, the market was so small that no new companies invested in manufacturing processes: Force Fins were still the originals. Conveniently, the stubby shape fits in a carryon bag, and I stuck them there in lieu of the Frisbee I usually carried.

I was prepared to answer any questions about my atypical visa. Had I had my Frisbee, I could toss it around while discussing the Frisbee Pie Company near Yale university and the students who tossed empty pie tins around until someone had the idea to patent the shape as a flying disc. At the time, it was an innovative toy. Patents expired after 20 years back then, and now flying discs are ubiquitous; saying Frisbee is like saying Kleenex, Zerox, Band-Aide, and Q-Tip for tissues, photocopies, adhesive bandages, and cotton swabs. I didn’t know if Cuba had similar brands or concepts, but I was ready to show examples of the differences between trademarks and patents and brands if anyone asked. Force Fins are much harder to toss back and forth than a Frisbee, but they can still be made into a fun learning lesson in the right context.

The senior official laughed politely and said something to the other, and he laughed too. My Spanish was rusty and I didn’t understand, but I smiled as if I had. The first put his hand through the open-toed fins and spread his fingers wide. He moved his hand in and out, and laughed and made a joke I didn’t understand, but I surmised that he was either being vulgar or joking about my feet. I was used to both. I was the runt of my family, only 5’11” in the morning (we all shrink about 1.5-2.5 cm by the end of the day because our spinal discs compress, ironically more from sitting than from standing or walking), but I inherited Partin-sized feet and hands that are disproportionately big for my height. It’s like having natural fins and flippers, though I still use Force Fins to dive. I chuckled back and shrugged ambiguously, as if to imply any one of the following: “What’s one to do?” or “I don’t know, I just work here.” or “That’s what she said!” They both laughed at whatever they imagined.

The senior official asked where I would be diving. I said Playa de Giron. He said it was beautiful there, and handed back my passport. I put it away and straightened my posture and tightened the hip strap on my backpack. The officials smiled, waved goodbye, and said buen viaje. I said gracias, turned around, and strolled out of the building, still ruminating about my mat, but smiling and strolling through the terminal like a duck moving slowly across a murky pond without anyone noticing that its feet are frantically paddling under the surface. I was so anxious to stretch that I didn’t notice anything remarkable inside the airport.

Per my visa, I had to use private rather than state-owned businesses, so I only peripherally glanced at the taxis as I left the airport grounds. I walked to a row of private drivers; Uber and Lyft were banned from doing business in Cuba under the archaic 1961 Kennedy embargo. Finding private cars was exactly as the Lonely Planet guide book had described, effortless and a good introduction to what many Americans expected to see: the 1950’s trapped in time. I scanned the options and chose a convertible that was older than I was but probably in better physical condition. It was buffed to a shine, and had an almost ineffable look of care that implied love rather than labor. I don’t know which type of convertible – I’ve never been good at identifying vehicles – but the top was down and it looked like all convertibles from that time period. To me, and what was on my mind, it was identical to the one in which Kennedy was riding through downtown Dallas when Lee Harvey Oswald – or someone else – shot and killed him at 1:26 pm on 22 November 1963. All I can guarantee is that the convertible definitely wasn’t Elon Musk’s red Tesla, which was on its way to the sun and being tracked by an app on my phone and a small army of amateur astronomers. But the convertible in front of Havana’s airport was just as remarkable as Elon’s. It was in pristine condition in a country where replacement parts were rare and expensive. Either an investor with a goal or an owner with a love affair cared for it. I voted for the later.

I stared with obvious admiration. I may not be a car person, but I appreciate anything that shows someone cares. The driver proudly said it had been his father’s, and that he maintained it himself and tried to keep it looking original. It was a fine automobile, whatever type it was, and we agreed on a price to a downtown plaza within walking distance of several casa particulares I had circled in the Lonely Planet. The America-based AirBnB was prohibited in Cuba.

I put my bag in the back seat and sat in the front. He had installed a surprisingly modern Bluetooth stereo and three-way door speakers, and a large digital counsol that played videos and waves of lights in sync with the music. He turned on something I had never heard but sounded like what was, I imagined, classic Caribbean Funk with a congo drum beat and brass horn riffs. We took off smoothly, and soon we were out of the airport and cruising down the melecon. The door speakers were clear without needing to be loud, and the driver seemed to love the sound as much as he loved his car. He tapped his fingers on the steering wheel, syncing with the stereo’s congo drums. I leaded back and sank into the slick vinyl seat that stretched from door to door and was more like a living room couch than any car seat since the 50’s. I rotated my cap backwards to keep it from blowing off, and tapped my fingers in sync with the driver; or as close as I could muster: I’ve never had rhythm.

A few minutes later we were cruising along the melacon. I stretched my arms above my head and took a deep breath of clean salty air, inhaling moisture and wide open space to replenish what the cramped seats and dry airplane air conditioners had depleted. We drove with the ocean on our right. In the mirror, I could see the massive Spanish forts, and laughed inside because the mirror said objects are closer than they appear: how true. I was finally seeing what I had only read about before, and the satisfaction of an A-Team plan coming together was just beginning to sink in. I extended my hand flat, like an airplane foil, and held it by the mirror and rotated my wrist back and forth to make my hand fly up and down like Superman flying over the wall of the melacon, just above ocean level. The reflection dwindled slowly, and soon I could see the forts and the ocean and a row of 1950’s cars parked along the melacon in what looked like a postcard beside my Superman hand; my smile broadened from the 1950’s warning on the mirror: objects are closer than they appear. Truer words had never been written about any postcard I had ever seen.

I looked at the driver and asked where I could get public WiFi. I must have said it poorly, because he turned down the radio and asked me to repeat the question. I said I would like a public WiFi card and access. (I didn’t know the word for ‘access,’ but I said the English word after a pause that, in San Diego, implied a Spanglish word followed.) He told me there was a kiosk near where we were going, Playa de San Francisco de Asi. I asked if he’d drop me off there. “Claro que si!” he said, and turned the radio back up and resumed tapping his fingers on the steering wheel. I road the rest of the way silently, smiling and watching stones in the wall of the melecon zip past my window while the ocean seemed to stay the same.

We arrived and I hopped out and gathered my bag and paid him. I asked if he knew of a hotel that existed in the 1960’s called The Havana Cabana. He shook his head and said no, that he had lived here all his life and hadn’t heard of it. He was about my age, so it could have been before his time. I said “Gracias,” and handed him a tip wrapped in a small red silk handkerchief. I stretched my colloquial Spanish to make a joke about it, but the pun was lost in translation and fell flat. He shrugged and waved and drove off.

Beside me was a vendor selling WiFi cards from a kiosk that also had chargers and cases. I bought a card with only 15 minutes and walked to where a handful of people were gathered around a few benches and a statue that the Lonely Planet said it was a statue of ______. They were all staring at their smart phones, and I assumed they knew where WiFi was most reliable. I set down my backpack and clipped it to a bench with a non-locking climbing carabiner, and pulled out my already outdated iPhone 8.

Despite having earbuds, I held my smart phone to my ear like an old flip phone. It transcribed voice mails, but I didn’t feel like rummaging for my reading glasses, so I told Siri to play voice mail. I kept the phone to my ear and moved into a modified warrior pose, with one hand on the phone and the other outstretched. I rotated my feet and squatted into the pose, trying to stretch my hamstrings and open my hips a bit until I could find a mat and do a proper job. My mind wandered to why I forgot the mat, and I was only partially listening to my phone. The first voice mail was from Wendy.

“Hey Jason, it’s Wendy. You’re probably in Cuba by now, but I thought I’d call just in case.”

She paused almost three seconds. Twice as long as usual.

“It’s not important.”

Pause.

Something felt wrong. I stood upright and tried to listen more closely.

“I just wanted to talk with you about my will.”

Another pause. I pressed the phone tighter to my left ear, and I was so perturbed by the voice mail that I fumbled a bit for my thick sausage of a finger to fit into my narrowed cauliflower-scarred right ear canal. I breathed quietly and leaned in to what she was saying.

There was another pause, and I heard a hint of a sound, as if she had inhaled deeply and began to say, “I…” I can’t explain why, but I suddenly thought that Wendy would commit suicide and that she was calling me first; she wouldn’t, and I had no reason to suspect she would, but that’s the thought that popped into my mind. My body tensed as springs wound up inside me, and I pressed the phone and my finger more tightly. I held my breath and listened. She sighed a subtle sigh, and said in what was obviously a forced cheerful tone, “Tell Cristi I said hello, and have fun in Cuba. Call me when you get back.” She hung up.

“It’s not big deal… You travel so much that I wanted to add Cindi as executor. We can talk about it later.”

Gut instincts can be wrong, so instead of calling her back immediately I kneeled by the bench and dug through my backpack and pulled out my reading glasses and earbuds, and rewound her message. The VA says I arrived in the army with perfect hearing, but I left with a 15% hearing loss in each ear at different frequencies, attributed to not having ear plugs for incessant machine gun fire and explosions during the first Gulf war. I was used to rotating my head to hear more clearly. Despite the stereo headphones, my head still rotated back and forth out of habit, as if trying to catch missing frequencies by whichever ear could. Anyone noticing probably thought I was moving my head to music and had jittery rhythm.

I listened to the entire message twice with earbuds. Nothing changed from what I heard the first time. The transcription made a few mistakes translating her southern Louisiana accent, and it missed her beginning to say, “I…”, but she had definitely began to tell me something and stopped before the first word manifested. I was fixated on what she had begun to say, and wondered what had sparked my feeling that she could kill herself. I heard nothing other than that one subtle sound and atypically long pauses.

I sighed. When she was drinking, Wendy sometimes called me to mumble about things about our past that no one else would understand. It had been getting worse the past few years.

Wendy was my mother, Wendy Anne Rothdram Partin. She was a teenage mother and abandoned me when I was an infant, but visited me once a month and taught me to call her by her first name so people would think I was her little brother.3 In fairness, she had a rough life. She was a single child of a single mother who fled an abusive husband in Canada and moved Baton Rouge; in 1963, just before Kennedy was shot and killed, Granny happened to move down the street from my dad’s grandmother, Grandma Foster, near the airport and a few miles from Glen Oaks High School, and in 1971 a 16 year old Wendy met the 17 year old drug dealer of Glen Oaks, Edward Grady Partin Junior. His father, Edward Grady Partin Senior, was the famous Baton Rouge Teamster leader who collaborated with US Attorney General Bobby Kennedy and infiltrated Jimmy Hoffa’s inner circle of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters. Hoffa went to prison solely based on my grandfather’s word. Around the time I was being conceived at a drug-fueled New Years party, Hoffa sent secret messagea from his prison cell to all mafia families that he’d forgive their debt – about $121 Million total, a lot of money back then – if “someone” could do “something” to get Edward Partin to recant his testimony.4

Wendy didn’t know any of this. She realized she was pregnant two weeks after losing her virginity to my dad but couldn’t afford a $150 abortion, so she hastily agreed to elope. They fled to Woodville Mississippi, an hour and a half away from Baton Rouge by car, where state laws allowed teenagers to marry without parental consent. They returned to Baton Rouge and were listed as Mr. and Mrs. Edward Partin in the phone book. Our home and neighborhood were plagued by a disproportionate number of explosions, arson, accidents, shot dogs, vandalized houses, and kidnappings. Wendy had two small nervous breakdowns, and when my dad was in Jamaica buying drugs wholesale she left me at a day care near Glen Oaks High and fled to California with a man she had just met. She returned on her own a few weeks later and divorced my dad, but by then I was in foster care under orders from Judge Pugh of the East Baton Rouge Parish 19th Judicial District. She fought the Partin family for seven years and eventually regained custody of me. But old habits are hard to break, and I still call my mother Wendy.

I don’t know why I felt that Wendy had called me with thoughts of suicide. She wouldn’t; but, on that day, I was overwhelmed by the feeling that she was reaching out to me as a last hope – I don’t know why. I stared at my phone and fidgeted in place and tried to discern my sudden concern from fatigue and an agitated mind.

Wendy never remarried and had no other children or surviving family, and sometimes she called me after more than a few glasses of cheap white wine to talk about things no one else would understand. In the past few years, her slurred voice mails were beginning earlier and earlier, and she was usually passed out by happy hour my time. I had been worried about her for years, but only for her health. But maybe she had reached her breaking point. Anyone can.

I rotated my left wrist and glanced at my watch despite the phone in my hand. I was wearing a 30-year analog Sieko dive watch. It had a rotating bezel and a glow-in-the-dark minute hand to tick off time underwater, and a thick black corrugated polymer band that circulated air to dry quickly. It was solar and hadn’t stopped ticking in 30 years. It was my talisman, a watch to connect me to past and present and to prepare for the future, an incorruptible analog glimpse into reality when I was deep for too long and susceptible to making unwise decisions due to nitrogen narcosis. I trust my life to it. I replace band changed before every sabbatical, and when I picked it up from Moe at About Time in San Diego I intentionally left it on Pacific Coast Standard time. I did the math; it was almost 5pm where Wendy lived in Saint Francisville, a town of about 1,500 people an hour upriver of Baton Rouge. I glanced at the voice mail time stamp, but it registered when I turned on my phone in Havana, not when she left her message. She could have called any time since I last checked messages in Houston, about eight hours or so before. She was probably already on her third bottle of wine.

I sighed and set the watch to Havana time. The feeling that she was contemplating suicide was so strong that – despite being glad to be off a plane – the thought that dominated was jumping on a flight to New Orleans, renting a car, and driving past Baton Rouge to reach Saint Francisville as soon as possible. I ignored the urge. I closed my eyes and stood still, and told myself that she’d be fine, that she was probably just drunk, or that one of her dogs had died. She was always upset when one of her rescue dogs either passed away or was adopted, and that led to opening the first bottle of wine earlier in the day. She sometimes got drunk and called to brainstorm about updating her will to include the West Feliciana Parish humane society. I was sure she’d sober up by tomorrow and be fine. But an analysis can be wrong.

“Fuck,” escaped my lips. I opened my eyes, put my earbuds in, and called her while I still had WiFi minutes.

Her mobile phone went to voice mail, probably because she was at home and the cell reception there was spotty. I called her land-line, but after four rings her vintage answering machine picked up. I called her mobile again, just to see if she’d answer. It went to voice mail.

I forced my voice to sound cheerful and said: “Hey Wendy, it’s Jason. I got your voice mail. I’m in Cuba. I’ll be offline for a month and diving and climbing in a remote areas, but I’m in Havana for a week and will check messages every day or two.”

I chuckled clearly enough for her to hear, and said, “The cell phone reception here is worse than in Saint Francisville, so I have to find spots where I can check messages.”

On a whim, I told her that I was calling from a plaza named St. Francis, after the patron saint of kindness to animals, and said that I hoped that coincidence made her smile. She had been fostering dogs for about fifteen years, volunteering at the West Feliciana Parish humane society next door to Angola Prison in Saint Francisville. If anything made her smile, it was kindness to animals and her work with the human society. I added a perfunctory “I love you” as sincerely as the man between Houston and Fort Lauderdale had wished me a good vacation, and reiterated that I’d check messages once every day or two. I hung up and sent Cristi a WhatsAp telling her I had arrived safely, that I had a cryptic message from Wendy, and to message me if she hears anything.

I didn’t feel like checking other messages, but I was already wearing my reading glasses and glanced at the names. Nothing jumped out, and I didn’t have many minutes left, so I called a few of the casa particulares I had circled in the guide book. In my best but most simple Spanish possible, I asked each one that had availability a few questions about the spaces because I didn’t want a cramped room. One that said their room had two exits: a private door with a lock and a glass door looking onto a small courtyard. It had another door to a private bathroom with a shower and hot water. Breakfast was included. It was a reasonable price and within walking distance from the plaza. I said that if it were okay, I’d be there after I had dinner, mas o menus a la nueve. They said that was fine, and told me what to look for outside of their building. Havana’s a densely packed city, and many of the neighborhoods look the same. They said to knock when I arrived, that they went to bed a las diez, mas o menus, so me showing up at around nine was no problema.

I packed away my earbuds, phone, and glasses. I stretched my hands above my head and twisted this way and that. I glanced around the square. It was happy hour. Small groups of mostly young professional-looking Cubans walked around, peering in bars and occasionally glancing at their phones. No obvious tourists were in sight. I scanned the perimeter and listened to competing beats of music, and generalized the clientele of each. I stopped at what looked most promising, a bar with wide open double doors next to a large open window, and with a diverse crowd that would make me less noticable. The evening sunlight was fading, so I could see inside the bar clearly enough. Just inside the doors, a six-person band was playing a guitar, three brass horns, a stand-up wooden bass, and a congo drum set. Past them was a stand-up bar with high bar stools, and a hand-written sign that I couldn’t make out but looked like a daily food menu; being hand-written implied it was fresh. There were about a dozen low-sitting tables with six chairs each generously spaced around the room, and a few booths opposite of the bar that would hold the same number of people. There were approximately twenty people inside, scattered in small groups among the tables and booths. The barstools I could see were empty.

I glanced at my wrist. I could still catch happy hour and begin my sabbatical with a Hemmingway Daiquiri, if only to raise a toast to Papa Hemmingway and say that I did it in Havana.

I didn’t see a sign with the bar’s name, but it stood out well enough and I could describe its location. I reached in my backpack and pulled out a flip phone mailed to me by an old army buddy, opened it, and waited for it to connect. I began typing a text message using the archaic buttons. The tactile feedback flowed from old muscle memory, and I automatically pushed buttons once, twice, or three times to spell the words in my mind. I wrote that I had arrived, and described the bar’s location. He responded immediately. I replied “yay!” and packed away the phone.

I shouldered my backpack, but didn’t bother to adjust the straps. The bar was only a phone’s throw away. I stretched my neck again, took a deep breath, and began walking towards the bar slowly and intentionally, like I had on the tarmac, ostensibly unrushed and trying not to limp. I arrived and peered inside and smiled. It was just as I imagined. I was finally ready to begin 2019’s sabbatical.

Go to The Table of Contents

Footnotes:

- The “minor domestic problem” was a reoccurring point in Hoffa’s defense strategy after my grandfather stood up in court as the surprise witness against him. Hoffa exclaimed, “Oh God, it’s Partin,” and his team of lawyers began attacking my grandfather’s character in retaliation of Bobby Kennedy’s media push to build it up, emphasizing that Bobby – or someone – purged America’s court records of my grandfather’s criminal history and told American media that the only witness against Hoffa had been in jail for a “minor domestic problem.”

What remained in records was still pretty bad, yet media focused on what FBI director J. Edgar Hoover told them, which was that my grandfather was a trustworthy family man and didn’t lie, and that he simply wanted to clean up American labor unions. Hoover went so far as to put his name beside Big Daddy taking a lie detector test in a six-page Life magazine focus on the Partin family in the same May 1964 issue that showed the newly appointed President Johnson and his family. In other words, there was no reason for most people to doubt Life magazine back then.

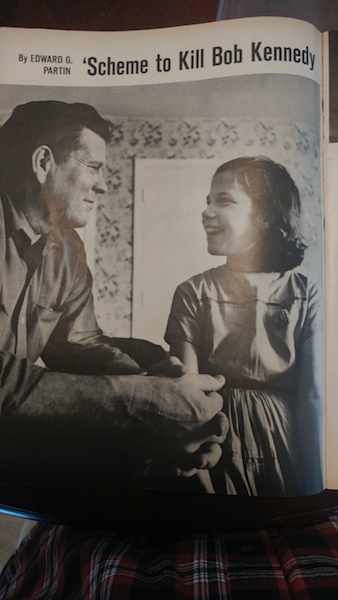

For the next 13 years of his life Hoffa, quoted Walter and Bobby’s lawyers by using “rabbit ears” to emphasize my grandfather’s “minor domestic problem.” In his second autobiography, published just before he vanished in 1975, published by Stein and Day, Hoffa summarized my grandfather using what evidence remained.

Let’s take a look at this “all-American boy” and his record, which was carefully kept from the jury by Judge Wilson and the government.

In December, 1943, he was arrested in the state of Washington for breaking and entering. Pleading guildy, he was senteneded to fifteen years in the state penitentiary, from which he escaped twice.

Freed, he joined the Marine Corps and was dishonorably discharged. He had been accused of raping a young black girl.

Becoming head of the Teamster local in Baton Rouge, he was charged by certain members with embezzling $1600 in union funds and he had been indicted on thirteen counts of falsifying records and thirteen counts of embezzlement.

While out on fifty thougsand dollars’ bond, he had been indicted in Alamama in Septermber of 1962 on charges of first-degree manslaughter and leaving the scene of an accident.

One day beofe the Alambama incictment, he surrendered on September 25th, 1962, to Louisiana authorities on a kidnaping charge, the “minor domestic problem” to which Life magazine had referred. He had assisted a friend in snatching the friend’s two small children from the friend’s wife, who had leagal custody of the children.”

Walter Sheridan, who spent a decade heading the FBI’s Get Hoffa Task Force under Bobby Kennedy and John F. Kennedy before that, couldn’t deny the facts presented by Hoffa and Warren. In his 1972 Opus, The Fall and Rise of Jimmy Hoffa, he addressed the growing realization that his star witness was controversial by expanding on my grandfather’s “minor domestic problem” only a bit less harshly than Hoffa. By then, Walter was a respected NBC news correspondent, so I assume his facts were thoroughly checked. He wrote:

“Partin, like Hoffa, had come up the hard way. While Hoffa was building his power base in Detroit during the early forties, Partin was drifting around the country getting in and out of trouble with the law. When he was seventeen he received a bad conduct discharge from the Marine Corps in the state of Washington for stealing a watch.One month later he was charged in Roseburg, Oregon, for car theft. The case was dismissed with the stipulation that Partin return to his home in Natchez, Mississippi. Two years later Partin was back on the West Coast where he pleaded guilty to second degree burglary. He served three yeas in the Washington State Reformatory and was parolled in February, 1947. One year later, back in Mississippi, Partin was again in trouble and served ninety days on a plea to a charge of petit larceny. Then he decided to settle down. He joined the Teamsters Union, went to work, and married a quiet, attractive Baton Rouge girl. In 1952 he was elected to the top post in Local 5 in Baton Rouge. When Hoffa pushed his sphere of influence into Louisiana, Partin joined forces and helped to forcibly install Hoffa’s man, Chuck Winters from Chicago, as the head of the Teamsters in New Orleans.

Chief Justice Earl Warren tried to dispel that myth in the 1966 supreme court case Hoffa vs The United States. He was the only dissenting supreme court judge, a 40 year veteran of the supreme court and a household name because of the newly published Warren Report on Kennedy’s assassination, where he mistakenly said that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone when he shot and killed Kennedy, and Jack Ruby acted alone when he shot and killed Oswald two days later. That was fresh on America’s mind when Warren focused on my grandfather in a multi-page missive permanently attached to Hoffa’s supreme court case.

Here’s a part of what Warren wrote:

Here, Edward Partin, a jailbird languishing in a Louisiana jail under indictments for such state and federal crimes as embezzlement, kidnapping, and manslaughter (and soon to be charged with perjury and assault), contacted federal authorities and told them he was willing to become, and would be useful as, an informer against Hoffa, who was then about to be tried in the Test Fleet case.

In 1966, Jimmy Hoffa began serving eight years in prison based soley on my grandfather’s word. To say Hoffa was pissed off is probably an understatement. ↩︎ - Coach’s family graciously gave their blessings for me to mention him in any memoir I wrote. His obituary was published in The Baton Rouge Advocate, published from Mar. 26 to Mar. 29, 2014:

Dale Glenn Ketelsen, 78, Retired Teacher and Coach, passed away March 22, 2014 at Ollie Steele Burden Manor with his wife by his side. A Memorial service will be held Saturday, March 29 at University United Methodist Church, 3350 Dalrymple Drive. Visitation will begin at 10 am with a service to follow at 12 pm conducted by Rev. Larry Miller. Dale is survived by his wife of 52 years, Pat Ballard Ketelsen, 2 sons: Craig (Emily) Ketelsen of Covington, La; Erik (Bonnie) Ketelsen, Atlanta, Ga and one daughter, Penny (Lee) Kelly, Nashville, TN; 5 grandchildren: Katie, Abby, Brian and Michael Ketelsen and Graham Kelly; a Sister-in-Law, Karen Ketelsen of Osage, Iowa, and numerous neices and nephews. He was preceded in death by his parents, 2 sisters and a brother. Dale was born in Osage, Iowa where he attended High School, lettering in 4 sports. Upon graduation, he attended Iowa State University as a member of the wrestling team where he was a 2 time All American and won 2nd and 3rd in the NCAA finals in Wrestling. He was a finalist in the Olympic Trials for the 1960 Olympics. After graduation, he joined the US Marine Reserves and returned to ISU as an Asst. Wrestling Coach. In 1961, he took a job as Teacher/Coach at Riverside-Brookfield High School in Suburban Chicago, Ill. While there, he also earned a Masters Degree from Northern Illinois University. In 1968, he was hired to start a Wrestling program at LSU in Baton Rouge, La. He was on the Executive Board of the National Wrestling Coaches Association and a founding member of USA Wrestling. He was the wrestling host for the National Sports Festival in 1985, He was instrumental in promoting wrestling in the High Schools in Louisiana. He was head Wrestling Coach at Belaire High School for 20 years and Assistant Wrestling coach at The St. Paul’s School in Covington, La. He was devoted to Faith, Family, Farm and the sport of Wrestling. Among his many honors were induction into the National Wrestling Hall of Fame and being named Master of Wrestling (Man of the Year) for Wrestling USA magazine. He was a long time member and Usher of University United Methodist Church. In lieu of flowers, the family asks that donations be made to Alzheimer’s Services, 3772 North Blvd., Baton Rouge, La. 70806. ↩︎ - My custody records, like most of my family history, are easily downloaded by anyone with internet access who knows my name and my parents name. Or you could walk into the East Baton Rouge Parish 19th Judicial District and ask for paper copies. Either way, Judge Pugh, a family court judge who removed me from the Partin family and alleggedly committed suicide a year later, isn’t named by name; that’s where my family’s daily talk and apocrophyl stories help me put together a few pieces of the puzzle. Pugh’s the “trial judge” referenced by Judge JJ Lottingger, the judge who stepped in and assumed my case around the time Jimmy Hoffa vanished on 30 July 1975. Here’s what Lottingger said about my family in his 26 September 1976 custody court ruling:

This is a suit by Edward Partin, Jr., plaintiff, seeking a divorce from his wife, Wendy Rothdram Partin, defendant, after having lived separate and apart for more than one year following a judgment of separation from bed and board. Plaintiff also seeks custody of the minor child, Jason Ian Partin, and the defendant reconvened asking that she be granted the permanent care, custody and control of the minor child.

The Trial Court had previously, by ex parte order, awarded the temporary care, custody and control of the minor to Mr. and Mrs. James Ed White. Following trial on the merits, plaintiff was awarded a divorce as well as the permanent care, custody and control of the minor child, with the temporary physical custody of the minor child to remain with Mr. and Mrs. James Ed White. The defendant has appealed this judgment as it regards the custody of the child.

This couple was married when plaintiff was 17 and the defendant was 16 years of age. Nine months following the marriage, they gave birth to young Jason. While we are not concerned with the facts surrounding the separation and divorce, it was apparently one of incompatibility as defendant testified that at the age of 17 she found herself married to a man who did not love her and so she left. Her testimony was as follows:

“As I say I was emotionally upset. I was receiving little support from Edward. I was scared, very confused. I didn’t know exactly which way to turn. I felt I had no one to listen and help with the situation at hand.”

Several weeks later she returned and lived with her husband again. She found that the situation hadn’t changed, and felt she had to get away again. She heard of a man who wanted someone to share expenses on a trip to California, so she quit her job and with her last wages left with him. She testified that she had no sexual relations with this man, and plaintiff does not accuse her of such. Following this trip she returned to Baton Rouge still emotionally upset. Her husband was suing her for separation and told her he was going to take custody of Jason. She went to live with her aunt and uncle, got a full time job with Kelly Girls paying $512.00 per month.

In February, 1975, the defendant’s mother was injured in an accident and she moved in with her to care for her. In September, 1975, following the recuperation of the mother she returned to live with her aunt and uncle.

During these above periods of time, the minor child lived with Mr. and Mrs. White. The Whites came to regard Jason as their own and, although the separation judgment awarded custody to the plaintiff with reasonable visitation privileges to the defendant, the Whites decided the defendant-mother could only see the child two days a month and that she could never keep the child over night. The reason the defendant did not contest custody at the separation trial was because at the time she felt unable emotionally and financially to care for her son.

[Judge Lottinger wrote a paragraph of legal jargon here, citing the “double burden” placed on Wendy by the deceased Judge Pugh to go above and beyond what was typically necessary to regain custody.]

We note that the petition for separation was grounded on habitual intemperance, as well as abandonment of the husband and the minor child. There are no other grounds listed for the separation nor for custody. The petition for the separation and custody of the minor child was not contested by the defendant, and a default judgment was granted. Defendant testified in the instant proceedings that the reason she did not contest custody in the separation proceeding was that she was not financially or emotionally capable of caring for the minor, and that knowing the Whites were going to be caring for him, she knew he would be in good hands.

Though the petition for separation had as one of its allegations “habitual intemperance”, the plaintiff in the instant proceeding testified that he had never accused his wife of drinking, nor had he ever seen her drink.

[Judge Lottinger goes on to cite a few precent cases, verdicts from previous judges in higher courts used to justify his opinions, a detail that’s less important in Louisiana’s version of the Napoleonic code, but still useful to show one’s logic and suggest unbiased decisions.]

The welfare of the child is the main issue that the Court is concerned with. This issue is more important than any wishes or wants the parents may have. Fulco v. Fulco, 259 La. 1122, 254 So.2d 603 (1971), rehearing denied (1971). As a general rule, and in particular where children of young age are involved, preference is given to the mother in custody cases. This preference is very simply explained, the mother is normally better able to care for the child and look after the education, rearing, and training necessary. Estes v. Estes, 261 La. 20, 258 So.2d 857 (1972), rehearing denied (1972).

No argument is made that the mother is not now morally or emotionally fit to care for the child, or that the house in which she lives is not a proper place to rear a child. In fact, the Trial Judge admitted that it was a fine home.

The Trial Judge has not favored us with written reasons for judgment, however, we must conclude from various statements by the Trial Judge that appear in the record that he could find no fault with the defendant, nor was there anything wrong with the house in which she lived. It thus becomes apparent to this Court that the Trial Judge applied the “double burden” rule to the defendant. We have already ruled that the “double burden” rule does not apply in this situation, and thus, under the established jurisprudential rules, we can see no reason why the defendant-mother should not be granted the permanent care, custody and control of the minor child with reasonable visitation privileges granted to the father.

In consideration of our above opinion, there is no need to discuss the specification of error as to the ex parte granting of custody to the Whites.

Therefore, for the above and foregoing reasons, the judgment of the Trial Court is reversed, and IT IS ORDERED, ADJUDGED AND DECREED that the defendant-appellant, Wendy Rothdram Partin, be and she is hereby granted the permanent care, custody and control of the minor, Jason Ian Partin, and IT IS FURTHER ORDERED, ADJUDGED AND DECREED that this matter be and it is hereby remanded to the Trial Court for the purpose of fixing specific visitation privileges on behalf of plaintiff-appellee Edward Partin, Jr. All costs of the appeal are to be paid by plaintiff-appellee.

Lottingger, incidentally, knew my grandfather and father well, though that’s not obvious in my custody report. He was a 30 year veteran of Louisiana legislative law, and served in the Baton Rouge state capital building down the road from Big Daddy’s Teamsters Local #5 headquarters. On behalf of three governors, he spent almost three decades and hundreds of thousands of taxpayer dollars trying to rid Louisiana of Big Daddy, similar to how Bobby Kennedy spent fifteen years and millions of taxpayer dollars trying to prosecute Hoffa. That’s probably why he was so kind to Wendy and took such a personal interest in my well being. ↩︎ - Frank “The Irishman” Sheenan talks about why he or the mafia didn’t just kill my grandfather, though they only knew a small piece of the puzzle. In his memoir, Frank wrote: “Partin was no good to them dead. They needed him alive. He had to be able to sign an affidavit. They needed him to swear that all the things he said against Jimmy at the trial were lies that he got from a script fed to him by Bobby Kennedy’s people in the Get Hoffa Squad.”

Frank was a soldier who questioned nothing – literally, he was a seasoned combat infantryman from two years in WWII, like a lot of mafia hitmen back then, who simultaneously became a Teamster leader and hitman for Hoffa. But even he didn’t know that Hoffa had lent the mafia families $121 Million to build Las Vegas casinos and fund Hollywood films, and that Hoffa had promised them to forgive all debt if “someone” could do “something” to get my grandfather to recant his testimony. If he didn’t, or if he died, Hoffa would continue to rot in prison. $121 Million was a lot of money back then, around $6 to $12 million per family in each major city, and almost $21 Million to Carlos Marcello’s family in New Orleans. To prevent them from killing my grandfather and keeping the money while Hoffa languished behind bars, Hoffa also said that he’d cut off all future funding from the Teamsters $1.1 Billion pension fund, which was an unfathomable amount of money back then and a major reason the Kennedys pursued him for decades with what was, at the time, the most expensive and drawn out pursuit against one man in American history. Hoffa was so powerful that he defied the Kennedys and ran the mob using only the $10 or so monthly dues from 2.7 Million truck drivers who paid in cash and trusted Hoffa to invest and grow their pension fund. Frank said: “Jimmy told me point-blank to tell our friends back East that nothing should happen to Partin,” and, like a lot of soldiers, he never questioned orders or asked why. Frank and others like him sent word that Ed Partin must live, but to do whatever it took to his business and family to convince him to change his testimony against Hoffa.

Though I know a thing or two about combat infantrymen, I’m not an expert on low level mafia hitman. But, I assume they knew how to read, or at least knew someone who did, and there were only a dozen or so Partins in the Baton Rouge phone book, and only one Mr. and Mrs. Edward G. Partin. In hindsight, knowing what we know now, you can imagine the understatement of Wendy’s testimony:

“I was scared, very confused. I didn’t know exactly which way to turn. I felt I had no one to listen and help with the situation at hand.”

It’s unremarkable that she had a nervous breakdown and abandoned me; what’s remarkable is that she came back and fought the Partin family face-to-face to regain me. Not even Jimmy Hoffa or Frank The Irishman Sheehan had thballs to do that.

↩︎