Edward Grady Partin : a part in his story

I arrived at my grandfather’s funeral early, but no one recognized me, so the police didn’t allow me in. I stood on my tip-toes and tried to look over the shoulders of reporters as they took photos of the mayor and LSU football players who had just arrived, but I didn’t see anyone who could let me inside.

Aunt Janice must have seen me peering over someone’s shoulder.

“Jason!” I heard her voice call. “Over here!”

I tried to stand even taller, and then I saw Aunt Janice waiving at me from inside the reception hall. I navigagted through the crowd, but was stopped by another policeman. “He’s family,” Aunt Janice told him as she walked towards me. He nodded his head politely, then returned to watching the mayor; though he, like the reporters, seemed more interested in the LSU football players.

Janice bent down and hugged me and said, “I’m so glad you came,” still squeezing me. She sniffed a few times to hold back her runny nose. She released her hug, stood up, wiped her eyes with a Kleenex, then used it to dry her nose.

“I’m sorry,” she said as she tucked the Kleenex into her purse and pulled out a clean one. “I haven’t stopped crying since Daddy died.”

Aunt Janice stopped sniffing and looked at me from my head down to my big feet and back up again. I knew what was coming.

“Look at you! You’ve grown since I saw you last,” she said from habit.

She always said I had grown, even if I hadn’t grown at all. I weighed 147 pounds that day, and had weighted 142 pounds when she saw me last, a year and a half ago. But I didn’t argue. I assumed all aunts felt that all nephews were bigger and all nieces were prettier than last time, no matter how long it had been.

She frowned, and looked up in the air as if trying to remember something, and asked the air, “How long has it been since I’ve seen you?”

I just mumbled something about it had been since before last year’s wrestling season, after my dad got out of jail the last time. She forced a smile and said, “Oh, that’s right. Well, you’ve grown so much! We’re so proud of you.”

My dad had always said I was the runt of our family, even though I was average compared to most kids in school my age. But to be fair to him, most people seemed small compared to my Partin family.

My grandfather was Edward Grady Partin, but everyone called him Big Daddy because of his size and his presence; he dominated every gathering with his smile and charm. Even at his funeral, he looked as if he owned the room.

His brothers were all just as big, just like my dad and uncles. Even Aunt Janice towered over me. But I rarely saw them smile, and they lacked Big Daddy’s charm.

Aunt Janice rested her hand on my shoulder as she looked around the crowded reception hall without needing to stand on her toes.

“Your dad’s here, somewhere,” she said with trepidation. She said a few more things I don’t remember, then she excused herself and went back to greeting family she hadn’t seen in a year or so, since she had moved in with Big Daddy to help care for him.

I glanced around for someone I knew, and saw Janice’s daughter, my cousin Tiffany, but she was talking to a group of family I didn’t know so I dind’t walk over.

Everyone liked talking with her. She was only a year older, but had always seemed much more mature. As a kid, I had looked up to her, literally and figuratively. She had always been taller than me, and she had become popular in school when I was not. She was beautiful, just like Janice and Mamma Jean, and her classmates had voted her prom queen last year.

Tiffany was smiling, but her eyes were puffy, like Aunt Janice’s. She knew how to fake a smile, she once told me. She said that was a secret to being popular, and being popular prevented people from asking about home; they assumed everything must be great.

She and I had the same eyes, Mamma Jean’s dark brown eyes. There was no mistaking that we were related, which may have been why we remembered each other from when we were little kids. In a way, she was my oldest friend.

Her brother, Damon, was beside her, and even though he was two years younger than I was, he was bigger. He had bright blue eyes like Uncle Kieth and Big Daddy, and he had inherited Big Daddy’s smile. His was genuine, though, even at the funeral. Or at least I thought so; I had known him since he was a baby, and his smile seemed the same even back then.

I had Mamma Jeans brown eyes, but I had also inherited Big Daddy’s smile. I looked around and realized that, besides Tiffany, I was the only smiling brown-eyed Partin; of the couple of dozen or so cousins, we were remarkably brown-eyed, except for a few with Big Daddy’s bright blue eyes.

Fortunately, I was a happy kid, so my smiles were genuine, though leas frequent around the Partins; Little Jake, Janice’s youngest boy, even said I looked “mean” whenever I was with mu dad.

But I rarely saw my dad, sometimes going months between hearing from him, and years between seeing him, so I was usually smiling. Unless I was around my mom, Wendy.

The Partin smile had gotten me out of trouble at school many times, probably like Big Daddy’s kept him out of jail.

I walked around the inside of Resthaven Gardens of Memory Funeral Home, and for the first time I began to understand that Big Daddy had been a big deal to more than just my family. I overheard people talking about the other guests and my grandfather, probably unaware that the little dark-eyed teenager was Ed Partin’s grandson; you’d have to look closely to see the family resemblance.

I look so much like my dad that when I met friends’s parents, many would recognize him through me, and instantly ask if I were related to Ed Partin. I used to ask which one, junior or senior, but I learned that if they loved me they had known Big Daddy, and if they told their daughter not to see me again, they hd known my dad.

I saw my dad at the same time he saw me, and he rushed towards me, opening his arms like Aunt Janice had done.

“Justin! I mean Jason, goddamnit!” He dropped to one knee, grabbed me by my shoulders, and said, “Come here, son,” as he pulled me into a hug with the grace of a truck driver changing a tire.

“I love you, son.”

“I love you, too, dad,” I said from habit, frustrated that he could still jerk me around. But I was still smiling, even though I hated being called Justin. When I was a kid, I joked with friends that I thought my name was Justin Jason Goddamnit Partin; but now it didn’t feel funny. I was an adult now. I didn’t want to be jerked around by a guy who couldn’t say my name right.

He pushed me backwards but held onto my shoulders. He looked me up and down, frowning, as usual, and said, “You haven’t grown. Boy, when I was your age, I wore the same sized jacket I wear now.”

When you were my age, I thought, you had already walked away from your son and had been arrested for selling drugs.

But I just smiled. That was the one of the few bits of advice Big Daddy offered: just smile at ‘em. Time Life Magazine even quoted him on that.

“You doin’ good in school, son?” my dad asked.

“Yeah”

“Gettin’ into any trouble?”

“No.”

“Good! Good! I love you, son”

“I love you, too, dad.”

Big Daddy taught me to smile often, and to use wisdom from the New Testament: answer only with ‘yeah’ or ‘nay.” And though he never told me he loved me, he said it so freely to most people in his life that I think everyone believed it by the time he died.

My dad was nervous, full of energy, and speaking too loudly for a funeral. I wanted to ask him to keep his voice down, like I would younger kids on the wrestling team talking during practice, but I didn’t want to cause a scene. I was an adult now.

I felt I was more adult than most of my family. But old habits are hard to break, and I was reverting back to feeling like a kid, even though I had been a legal adult for six months, since before I turned 17.

No one could find my dad for several months, and a judge had me when I was 16. By Big Daddy’s funeral, I had been divorced from all families, and I had been legally free to make my own choices since the beginning of my senior year in high school. I had written my dad a few letters – he didn’t have a phone – but I never learned if he received them.

“You got your braces off,” he said as he kept trying to spread my lips apart. I mumbled that I had them taken off a few months ago, before I joined the 82nd, but he either didn’t hear me or wasn’t listening.

He stopped reaching for my lips, and began to talk incessantly about how he passed the GED, started college, and fought a bunch of college administration assholes in court so that he could keep wearing a shirt that said, “Fuck U.S. Actions in Panama!”

He had designed the shirt himself, using a mostly clean t-shirt and a black marker, and he had worn it for a week after the United States invaded Panama a few months before, during Christmas. His voice raised as he ranted, and he pointed a finger or tapped my chest with it to emphasize each of the many points he was making.

Fortunately, someone who worked at the funeral home walked over and asked him to lower his voice. As my dad began ranting about free speech and pointing his finger at the infinitely more patient usher, I used the opportunity to walk away from my dad and look for Grandma Foster.

Grandma was Big Daddy’s momma, and I alway wondered how such a tiny woman gave birth to such big men. She was around 5 feet tall, and even I had to lean over to hug her. She hunched over and wrinkled, and as a kid I thought she looked like Yoda, the wrinkled and green muppet, but pale white and with a sweet smile and cloudy blue eyes that had been obscured by cataracts. She had been a little old lady when I first met her, ten years before.

I saw her crying against Uncle Doug’s big Partin chest. She looked up at him and bawled “You ain’t sup’osed t’ outlive yer chil’ren…” then fell back into his arms and cried some more.

Uncle Don was there, too. He and Doug were her two surviving sons. Doug had been elected president of the local teamsters while Big Daddy was in prison, but Don had eschewed the teamsters, and put his energy into raising Joe.

Uncle Joe had become a football coach and high school principal of the Zachary High School Broncos. I knew who he was, and even competed against his school (I had pinned their 145 pounder in the third round that year) but I had never met Coach Joe or his son, Jason Partin, a football star at Zachary High School. It was only a coincidence that we had the same name.

Having the same name as a popular football plater – the principal’s son – caused confusion every time the Broncos hosted my team for a wrestling match. Yet I still hadn’t met Joe or Jason. As I joked: I was a only small part in the family.

I saw Jason Partin for the first time that day, He was bigger than me, of course. He was uninterested in the Teamsters, which is probably why I hadn’t met him at the local union headquarters with Kieth and Doug. Maybe that’s why I never met a lot of my family; they weren’t as curious about their Partin family.

I walked over to Grandma Foster. I don’t think Don recognized me, but Doug said it was good to see me. He told Joe I was Ed’s son, and Joe nodded as if that explained a lot. “Nice to meet you,” Coach Joe said. That was all he had ever said to me. But I saw in his eyes that he loved Grandma, too.

Grandma looked up at me with tears pooled in the wrinkles across her cheeks. Her cataract-covered blue eyes squinted from the breadth of her sudden and genuine smile, and she let go of Doug and held out her arms so that I could bend over and hug her. We squeezed each other softly and said nothing for a few moments.

Over the years, I had grown to love Grandma. She had told me about my Partin family, like she had told them about me, and that’s the only reason Joe and Jason knew who I was. If I felt connected to the family, it was only because of Grandma Foster and Aunt Janice; but, ironically, they never spoke after Grandma welcomed Big Daddy’s new wife and family into her home. They were at the funeral, but I hadn’t seen them yet. Even if had, I doubted I would have recognized them, because they wouldn’t have Mamma Jean eyes, they would have a mix of Big Daddy and his wife after Mamma Jean, Kay or Kathy, or something like that. I had only met a few of them at Grandma Foster’s house.

I loved my little Grandma, and I felt her sadness, and I shed tears with her. She misread my tears as my own sadness, and she moved her hands to mine and squeezed one with both of hers and smiled and said, “I’m glad you came. You look so handsome, just like your daddy. You was always a good boy.”

Her smile faded and she looked away and said, “Ed was a good boy, too.”

I didn’t know if she was talking about Big Daddy or my dad; he had stayed with her when he was my age, and she was one of the first people to see me as a baby.

“You a good boy, too,” she repeated. “You was always good to y’er Grandma.” She paused, and swayed my hands back and forth so slightly no one watching would have noticed, then began crying again.

I hugged her for a few minutes while Doug waited, then Doug stuck out his hand graciously. I shook it. My paw rested respectfully in his mitten – I had remarkably big hands and feet – and I squeezed tightly enough to show I was strong for my size, but not so tightly that it would be obvious I was trying.

“We’re glad you’re here. You’re family.” Doug’s smile seemed genuine, and I stood up more straight and thanked him and said I was sorry for his loss, and he thanked me with a smile and trembling lip as another tear oozed from one of his blue eyes.

“Your dad’s here,” he said, not looking around, but watching me and my reaction. I told him I had seen him, and we had spoken. I couldn’t tell if he had heard my dad ranting about Panama and Reagan and the war on drugs.

Some of Big Daddy’s grandkids from his second marriage showed up at the funeral home and walked over, so I excused myself from Doug and Grandma and mumbled something to the cousins I barely knew. I walked around the funeral home again, and overheard people talking about the pallbearers.

Doug was one of Big Daddy’s six pallbearers, and he was standing near the casket with the other five. They were all huge men. I didn’t know them, but I had learned that they were a big deal by overhearing what people said. Two were former LSU football players, and in Baton Rouge, home of the Louisiana State University Tigers, where college football players were respected more than the mayor and almost as much as Big Daddy.

One of the pallbearers, Billy Cannon, had even won the Heisman Trophy, I heard people say. I had no idea what that was, but it must have been a big deal, because so many people mentioned it.

The minister announced that services would begin, and asked the family to take their seats. My dad tried to get me a seat – they had forgotten about me when planning the funeral – but I said I was preferred standing. I found a place against a wall near two FBI agents.

They weren’t even trying to hide, I thought. They looked like the FBI agents in movies: short and slicked-back hair, sunglasses even indoors, and – I’m not making this up – an earbud with a curly white wire coming from their ear to their shoulder and disappearing under their coats. They even spoke into their coat lapels during the services. This was 1990, before cell phones and wireless technologies, and apparently before FBI agents realized that they were charactertures of themselves from movies, like the 1980’s movie about Big Daddy and Hoffa and the FBI.

I had seen them earlier, and had wondered why no one else thought they were as obvious as I did. Maybe people at the funeral didn’t watch the same movies that I did, and Men in Black or The Matrix hadn’t even been made yet.

The two agents had been asking my family what Big Daddy had told them in his final few weeks. They would have recognized the family by their blue eyes and smile, and because the family had assigned seats. They never asked me anything, and I don’t remember most of what they asked, or what they whispered into their coat lapels. I only recall a few words and names that the crowd spoke loudly enough for me, and presumably the FBI, to overhear.

“Billy Cannon was his bodyguard,” someone said.

“Ha! As if Ed needed one,” said another.

“…was Hoffa’s bodyguard once…”

“… ended up dead, at the bottom of the Amite River, with the safe…”

“… he died, too…”

“… Marcello…”

“what do you call a Teamster wearing a tie? The defendant! Ha!”

“Or the deceased!”

“… Ruby …”

“… his granddaughter’s gorgeous…” (she was)

“… the Heismann Trophy! And he’s a dentist now.”

I lingered by the two FBI agents, hoping they’d ask me questions so that I could see if I could answer like Big Daddy. They had been asking my cousins what he had told them in the weeks leading to his death, and, ironically, I had been one of the few to have spent time with him the , probably because Aunt Janice had been his caretaker and she always went out of her way to include me. But, I wouldn’t have told them anything; Grandma had taught me not to trust the FBI. Go straight to the top, she said.

The FBI didn’t ask me anything, so I walked away and overheard more than a few women say that Big Daddy was handsome, just like his son, Keith, and his grandson, Damon. It seemed to me that women preferred tall blonde men with bright blue eyes and nice smiles. I only had the smile. Maybe that’s why I felt invisible at the funeral.

Most of the talk I overheard wasn’t gossip or jokes, it was appreciation for the jobs Big Daddy had brought to Baton Rouge and how he had fought for fair wages. Men spoke of how he saved their family and stood up for them, and how they looked up to him. It seemed that women wanted him, and men wanted to be like him. Everyone there loved him. He could do no wrong in their eyes.

My 5th grade teacher was there, and so was one of my principals and a few teachers I recognized from different schools, but they didn’t recognize me, probably because it had been a long time.

I overheard them speaking about teacher union strikes, and how Big Daddy got the Teamsters to support the teachers and get them more pay and benefits. They all talked about when they were on strike and not getting paid, and would have quit the strike to go back to work if Big Daddy hadn’t given them money from his own pocket; that part had been in Time Life, too.

They probably didn’t know it wasn’t his cash, that it was the Teamsters or the mafia’s money, and my teachers didn’t know or recall that Big Daddy asked for it back from the teachers union after reporters left.

I believed I knew more about history than my history teacher, even though I’m pretty sure I failed her class.

Several of my teenage cousins spoke to the crowd at Big Daddy’s funeral. They were all better speakers than I was, and even though they lived in Houston, they didn’t have my mumbly southern accent. People listened to them and said how smart and sweet they were. They told sweet stories about him that I had never heard, and all of them ended by saying Big Daddy was in heaven.

I thought that was funny, and not just because it was a play on the Lord’s prayer, ‘Our father, who art in heaven,” but mostly because I wondered if we had different grandfathers or we different understandings of what it took to go to heaven.

I knew Big Daddy had broken at least seven of the ten commandments, including the big ones: thou shall not kill, steal, commit adultery, or bear false witness. And though “thou shall not rape,” and “thou shall not beat witnesses,” weren’t commandments, I figured that God would update the rules if Big Daddy actually made it to heaven.

After the service, people stood up and began walking to the reception hall. I was one of the first there, because I had been standing near the door, and I stood near the flowers sent to Big Daddy’s funeral and studied the most ostentatious floral arrangement anyone had ever seen. It was big as a school classroom’s chalk board, and made from bright yellow flowers arranged to look like the side view of an 18-wheeler truck.

Across the truck bed, written in red flowers, was, “From Local #5,” and under the truck was a plaque with the Teamster’s logo, two horse heads left over from the 1800’s, when teamsters drove horse wagons instead of trucks. The plaque said, “The International Brotherhood of Teamsters.” Like Cain and Able, I thought. I associated the Teamsters with fighting.

My dad was crying when he walked into the reception hall. He saw me by the 18-wheeler and walked over and put his arm gently around my shoulder. He sobbed silently by my side for a few minutes, then he pulled me closer and told me he loved me. He said my name correctly that time. I knew he was a good person, and not just because Grandma said so. But he was hard a hard man to love.

Grandma Foster came out, crying loudly. Doug walked with her, and he kept one hand on her shoulder. Keith and the other pallbearers followed, but only Doug and Keith were crying. They all shook hands with people near the flower arrangements, and talked about memories with Big Daddy. Billy Cannon smiled a lot and bright white teeth. He was probably an excellent dentist.

Doug saw my dad and me, and walked over. His warm smile belied the sadness in his puffy bright blue eyes, and he stuck out his big hand and said softly, “I’m sorry for your loss, Ed. Your daddy was a good man. We’re all gonna miss him.”

My dad stood upright and narrowed his dark brown eyes and looked intense and angry. His eyebrows were angle low in anger, and almost touched his nose. His jaw tightened and his frown narrowed into a scowl. Suddenly, his arm flew from my shoulder and slapped Doug’s hand away and he shouted, “Fuck you, Doug!”

My dad stepped forward and shoved Uncle Doug, knocking him backwards. I swear I felt the shockwaves from my dad’s hands hitting Doug’s chest with an audible Thump!, and I heard Doug’s breath leave through the pursed lips of his shocked countenance, and I watched him flail his arms as he stumbled backwards. He wasn’t smiling.

He fell against the 18-wheeler with his arms spread like Jesus on a cross, and as he lowered his arms and stood up straight my dad was already there, clenching Doug’s coat lapel with his left hand and swinging his right fist towards his uncle’s face.

But Billy tackled my dad before the punch landed. It t took Billy and four Teamsters to drag my dad away, and as they left, I recall my dad shouting, “Fuck U.S. Actions in Panama!” I don’t remember if the FBI did anything. I assumed he was shouting at them, because they were the closest thing to Ronald Reagan he’d ever see, especially with his temper.

There’s nothing like a fight to disrupt the flow of a funeral. I left without saying goodbye to anyone, and walked to the parking lot and put on my letterman jacket and motorcycle helmet. I straddled my bike and started the engine, and rev’ed the gas a few more times than necessary, hoping someone would notice I was leaving. No one did, so I pulled out of the parking lot of Resthaven Garden of Memories funeral home and headed home.

I accelerated onto Airline Boulevard. After a few traffic lights, I saw the sign for Interstate 12, and I headed up the on-ramp and accelerated as much as I could. My bike was small, a 500cc Honda Ascot, but to me it seemed as if I were flying towards the sky like Superman.

I tucked my body against the fuel tank as I flew along the raised interstate above the streets of Baton Rouge. I lost track of time, and didn’t see where I was going until I was flying over the Mississippi River. Shit! I thought. Not again.

I always missed the exit between I-12 and I-10, and always had to turn around on the other side of the Mississippi. The river was almost a mile across at this point, and now I was on I-10, full of 18-wheelers going from the ports of Baton Rouge and New Orleans to the rest of the country, and those big trucks couldn’t accelerate uphill as fast as my motorcycle, so I slowed down and sat upright and looked up and down the Mississippi on the slow mile ride across the Baton Rouge bridge.

I watched the tug boats push barges a hundred feet below, and in the distance I saw one of the big ocean liners coming up from the Gulf of Mexico and past New Orleans. They’d have to stop at the Baton Rouge port and transfer their goods to the Local #5 Teamsters, and the teamsters would dribe their trucks across the country, along I-10.

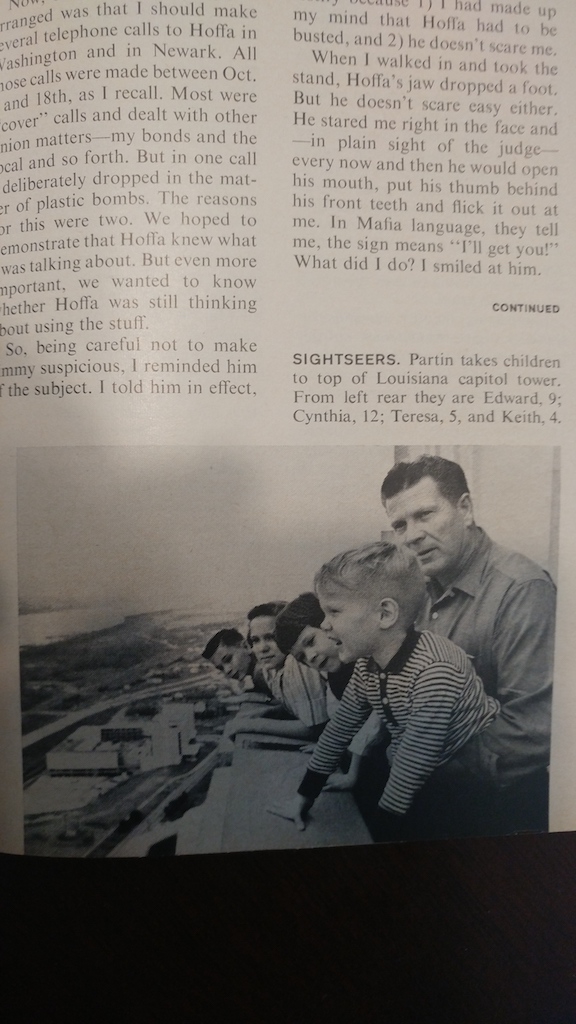

Once on the other side of the Mississippi, I followed the clover-leaf exit in a giant loop that pointed me back towards Baton Rouge, and flew like Superman again. This time, I looked for signs and saw one with an airplane, and I took the exit towards Baton Rouge’s airport and looked for the state capital building, the tallest building in Louisiana and the tallest capital in America. We were all proud of that. Time magazine had chosen the top of our state capital for a photo of Big Daddy and my dad and Keith, when they were little boys, just before the Hoffa trial in Chatanooga.

I slowed down and took an off-ramp, descending from the elevated interstate and into downtown Baton Rouge. I kept the state capital in my sights, and navigated through stop signs until I reached the levee, then kept the levee on my right until I reached the capital grounds and pulled into the empty parking lot.

The parking lot was almost empty – not many people ventured downtown back then, because it was full of black people and drug dealers, most people said, though they may have used different words. They weren’t completely wrong, I thought. Sonny, a drug dealer I remembered from childhood, lived a few blocks away, but I didn’t want to see him that day.

I looked up at the capital building, up the steps labeled with each state’s name, and remembered running up and down those steps during summer wrestling camps. I saw us at the top, jumping up and down with our arms in the air, like Rocky.

A few of us would even go inside, skipping the elevator with its bullet holes from when Governor Huey Long was gunned down, and trying to run up the ancient staircase to the observation deck 34 stories in the sky. We’d pant and gasp and give high-fives and look over the Mississippi River almost every morning, every summer.

I’d miss that when I left for the 82nd in a few months, I thought.

I felt my cheeks twitching, like my dad had before he slapped Doug’s hand, and I looked around to get my bearings so I could leave. I saw the same road I had run down many times, and slowly steered my bike towards it. A few turns later, I was at the downtown wrestling camp.

I pulled my bike into the alley behind the camp, an old garage with metal columns supporting a ceiling still covered in asbestos, and used my key to get inside. I flipped on the lights, took off my shoes, grabbed a mop and bucket, and cleaned the wrestling mat out of habit.

The smell of fungicide on a freshly mopped wrestling mat spoke to me, and I put away the mop bucket and stepped back onto the mat after letting it dry for a few minutes. I shot across the mat, stepping forward deeply with one leg and keeping my chest parallel with the wall, then pulling my hands tightly to my chest as I stood up and allowed the trailing leg to slide along the mat until I was in a good stance, then I repeated the shot with the other leg leading.

I shot back and forth across the mat until I had a slight sweat and was breathing heavily, and my thoughts were gone and my mind was clear and focused; though I wouldn’t have said it that way back then, because I didn’t realize why I loved wrestling so much.

When I wasn’t thinking, I picked up one of the throw dummies that padded one of the steel poles holding up the two-story ceiling, and I practiced throwing the dummy. I stood it up, slid my left arm into its right arm pit, and pushed its arm up with my left shoulder. I paused, allowing time for the dummy to push back down, then stepped forward and put my right foot near my left as I wrapped my right arm around the dummy’s head and simultaneously pivoted my hips into his and added to the momentum he had begun by trying to force his arm back down. That dummy fell for it every time.

I threw the dummy until I was dripping with sweat, and on my final throw I let him hit the ground harder than would be allowed in a tournament. The loud thump! echoed in the gym, and satisfied my soul in ways I recognized but didn’t understand. I pulled up with my right arm – I wasn’t ambidextrous with throws like I was shots, so I always landed on my right side – and arched my hips into the air to put my full weight onto his chest as I pulled his head up, and I pinned him. The crowd went wild, but instead of standing to have my arm raised by the referee, I rotated my body and looked up at the asbestos covered ceiling with my head resting on the dummy.

I don’t remember how long I sat there, but it was getting dark when I turned off the lights and laid back down on the mat to sleep. My mind was full of memories, more like impressions of intense emotions than detailed memories, but I drifted off to sleep anyway, maybe because the fungicide was probably more toxic than the asbestos. And even though I fell asleep with memories on my mind, I didn’t dream that night. I don’t know if the dummy did.