The life and times of Edward Grady Partin, 1924 – 1990

In 2020 hindsight, it’s easy to see how my grandfather fooled so many people, and why the FBI showed up at his funeral, asking about how he planned to kill the president, and where Hoffa’s body was.

I wrote this as a short story in 2020; it’s full of mistakes, lies, run on sentences, and errors I mad while writing from memory. But, it was the best I could do at the time. Recent versions are on my home page, under “book,” and I keep old blog posts like this one and works-in-progress in a blog.

This is all true, to the best of my knowledge. It’s the history of my grandfather, Edward Grady Partin, from when he was born in 1924 to his funeral in 1990, when I was a 17 year old young man and unaware of the full extent of his part in history.

In 1992, two years after my grandfather’s funeral, 60% of the JFK Assassination report was published in the U.S. National Archives after President Bill Clinton reviewed it. As early as 1992, the public could have known that in 1976 the US Congressional Committee on Assasinations determined that people behind the scenes helped or manipulated Lee Harvey Oswald into killing President Kennedy. One of those men was Hoffa; Oswald had trained in the Louisiana civil airforce a few miles from my childhood home.

In the years sine Bill Clinton released 60% the JFK Assassination report, every president has released a little bit more. By 2020, approximately 98.6% was released. I don’t know what is in the 0.4% retained by President Trump, but I downloaded what was available and deleted everything without “Partin” and “Hoffa” and “Kennedy” within a few sentences of each other. I copied the result below:

Findings:

The Committee believes, on the basis of the evidence available to it, that President John F. Kennedy was probably assassinated as a result of a conspiracy. The Committee is unable to identify the other gunman or the extent of the conspiracy.

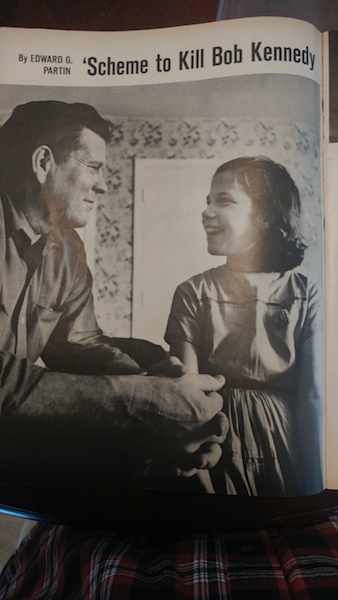

The committee found that Hoffa and at least one of his Teamster lieutenants, Edward Partin, apparently did, in fact, discuss the planning of an assassination conspiracy against President Kennedy’s brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, in July or August of 1962.(330)

Hoffa’s discussion about such an assassination plan first became known to the Federal Government in September 1962, when Partin informed authorities that he had recently participated in such a discussion with the Teamsters president. (331)

In October 1962, acting under the orders of Attorney General Kennedy, FBI Director Hoover authorized a detailed polygraph examination of Partin. (332) In the examination, the Bureau concluded that Partin had been truthful in recounting Hoffa’s discussion of a proposed assassination plan.(333) Subsequently, the Justice Department developed further evidence supporting Partin’s disclosures, indicating that Hoffa had spoken about the possibility of assassinating the President’s brother on more than one occasion. (334)

In an interview with the committee, Partin reaffirmed the account of Hoffa’s discussion of a possible assassination plan, and he stated that Hoffa had believed that having the Attorney General murdered would be the most effective way of ending the Federal Government’s intense investigation of the Teamsters and organized crime.(335) Partin further told the committee that he suspected that Hoffa may have approached him about the assassination proposal because Hoffa believed him to be close to various figures in Carlos Marcello’s syndicate organization.(336)

Partin, a Baton Rouge Teamsters official with a criminal record, was then a leading Teamsters Union official in Louisiana. Partin was also a key Federal witness against Hoffa in the 1964 trial that led to Hoffa’s eventual imprisonment. (337)

While the committee did not uncover evidence that the proposed Hoffa assassination plan ever went beyond its discussion, the committee noted the similarities between the plan discussed by Hoffa in 1962 and the actual events of November 22, 1963. While the committee was aware of the apparent absence of any finalized method or plan during the course of Hoffa’s discussion about assassinating Attorney General Kennedy, he did discuss the possible use of a lone gunman equipped with a rifle with a telescopic sight, (338) the advisability of having the assassination committed somewhere in the South, (339) as well as the potential desirability of having Robert Kennedy shot while riding in a convertible. (34O)

While the similarities are present, the committee also noted that they were not so unusual as to point ineluctably in a particular direction. President Kennedy himself, in fact, noted that he was vulnerable to rifle fire before his Dallas trip. Nevertheless, references to Hoffa’s discussion about having Kennedy assassinated while riding in a convertible were contained in several Justice Department memoranda received by the Attorney General and FBI Director Hoover in the fall of 1962.(341)

Edward Partin told the committee that Hoffa believed that by having Kennedy shot as he rode in a convertible, the origin of the fatal shot or shots would be obscured. (342) The context of Hoffa’s discussion with Partin about an assassination conspiracy further seemed to have been predicated upon the recruitment of an assassin without any identifiable connection to the Teamsters organization or Hoffa himself.(343) Hoffa also spoke of the alternative possibility of having the Attorney General assassinated through the use of some type of plastic explosives. (344)

The committee established that President Kennedy himself was notified of Hoffa’s secret assassination discussion shortly after the Government learned of it. The personal journal of the late President’s friend, Benjamin C. Bradlee, executive editor of the Washington Post, reflects that the President informed him in February 1963 of Hoffa’s discussion about killing his brother. (345) Bradlee noted that President Kennedy mentioned that Hoffa had spoken of the desirability of having a silenced weapon used in such a plan. Bradlee noted that while he found such a Hoffa discussion hard to believe “the President was obviously serious” about it. (346)

Partly as a result of their knowledge of Hoffa’s discussion of assassination with Partin in 1962, various aides of the late President Kennedy voiced private suspicions about the possibility of Hoffa complicity in the President’s assassination.(347) The committee learned that Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy and White House Chief of Staff Kenneth O’Donnell contacted several associates in the days immediately following the Dallas murder to discuss the possibility of Teamsters Union or organized crime involvement. (348)

In an interview with a newsman several weeks before his disappearance and presumed murder, Hoffa denied any involvement in the assassination of President Kennedy, and he disclaimed knowing anything about Jack Ruby or his motivations in the murder of Oswald. Hoffa also denied that he had ever discussed a plan to assassinate Robert Kennedy. (358)

As in the cases of Marcello and Trafficante, the committee stressed that it uncovered no direct evidence that Hoffa was involved in a plot on the President’s life, much less the one that resulted in his death in Dallas in November 1963.

In addition, and as opposed to the cases of Marcello and Trafficante, Hoffa was not a major leader of organized crime. Thus, his ability to guarantee that his associates would be killed if they turned Government informant may have been somewhat less assured. Indeed, much of the evidence tending to incriminate Hoffa was supplied by Edward Grady Partin, a Federal Government informant who was with Hoffa when the Teamster president was on trial in October 1962 in Tennessee for violating the Taft-Hartley Act. 11

It may be strongly doubted, therefore, that Hoffa would have risked anything so dangerous as a plot against the President at a time that he knew he was under active investigation by the Department of Justice.12

Finally, a note on Hoffa’s character. He was a man of strong emotions who hated the President and his brother, the Attorney General. He did not regret the President’s death, and he said so publicly. Nevertheless, Hoffa was not a confirmed murderer, as were various organized crime leaders whose involvement the committee considered, and he cannot be placed in that category with them, even though he had extensive associations with them. Hoffa’s associations with such organized crime leaders grew out of the nature of his union and the industry whose workers it represented.

Hoffa was in fact facing charges of trying to bribe the jury in his 1962 trial in Tennessee on November 22, 1963. The case was scheduled to go to trial in January 1964. Hoffa was ultimately convicted and sentenced to a prison term. Partin was the Government’s chief witness against him.

The rest of my story comes from news reports, other peoples’ autobiographies, including Hoffa’s. He dedicated an entire chapter to my grandfather, and to the undeniable fact that our government influenced national media. They made Edward Partin seem different than he was, all to influence a future jury that sent Hoffa to prison for, ironically, jury tampering. He was convicted based on Ed Partin’s testimony, which all of us knew was a lie.

It was worse than a lie, to people as faithful as my grandmother. She knew it was bearing false witness. That’s a sin, she told me. So’s stealing and killing, I reminded her; Ed Partin did those things, too, unfortunately. I can not express how I wish the girl he raped and the people he killed found peace. Mamma Jean and I would discuss how Big Daddy, which is what Partin’s seven children and many grandchildren called him, fooled so many people. She said that she agreed with what Jimmy Hoffa said after he spent five years in prison for Big Daddy’s testimony, which was likely false. Hoffa who wrote, “Edward Grady Partin was a big, rough man who could charm a snake off a rock.”

Big Daddy fooled more people than Mamma Jean, Hoffa, and the jury that sent Hoffa to prison. He fooled the U.S. Supreme Court, or at least all of the Chief Justices except Chief Justice Earl Warren. Warren had authored the 1964 Warren Report, the official U.S. verdict that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone to murder President Kennedy (the 1976 congressional investigation concluded differently, but by then most people had forgotten the details from 1964). But even the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court hadn’t seen the FBI reports that I copied from the National Archives in 1992. Those reports were overseen by J. Edgar Hoover, the FBI director, and Attorney General Bobby Kennedy, the president’s brother, and could explain why Bobby Kennedy publicly expressed disdain for Hoffa: privately, he suspected Hoffa was behind the president’s death, and did whatever was necessary to find a witness who could send Hoffa to prison. He helped my grandfather get out of jail in exchange for testifying against Hoffa, and only Chief Justice Warren wasn’t fooled by Big Daddy’s charm.

In the Supreme Court case of Hoffa vs. The United States, Warren tried to warn America that relying solely on my grandfather’s testimony to send a man to prison threatened our system of justice. He wrote:

Here, Edward Partin, a jailbird languishing in a Louisiana jail under indictments for such state and federal crimes as embezzlement, kidnapping, and manslaughter (and soon to be charged with perjury and assault), contacted federal authorities and told them he was willing to become, and would be useful as, an informer against Hoffa, who was then about to be tried in the Test Fleet case. A motive for his doing this is immediately apparent — namely, his strong desire to work his way out of jail and out of his various legal entanglements with the

State and Federal Governments. [Footnote 2/2] And it is interesting to note that, if this was his motive, he has been uniquely successful in satisfying it. In the four years since he first volunteered to be an informer against Hoffa he has not been prosecuted on any of the serious federal charges for which he was at that time jailed, and the state charges have apparently vanished into thin air. Shortly after Partin made contact with the federal authorities and told them of his position in the Baton

Rouge Local of the Teamsters Union and of his acquaintance with Hoffa, his bail was suddenly reduced from $50,000 to $5,000 and he was released from jail. He immediately telephoned Hoffa, who was then in New Jersey, and, by collaborating with a state law enforcement official, surreptitiously made a tape recording of the conversation. A copy of the recording was furnished to federal authorities. Again on a pretext of wanting to talk with Hoffa regarding Partin’s legal difficulties, Partin telephoned Hoffa a few weeks later and succeeded in making a date to meet in Nashville, where Hoffa and his attorneys were then preparing for the Test Fleet trial. Unknown to Hoffa, this call was also recorded, and again federal authorities were informed as to the details.

Upon his arrival in Nashville, Partin manifested his “friendship” and made himself useful to Hoffa, thereby worming his way into Hoffa’s hotel suite and becoming part and parcel of Hoffa’s entourage. As the “faithful” servant and factotum of the defense camp which he became, he was in a position to overhear conversations not directed to him, many of which were between attorneys and either their client or prospective defense witnesses. Pursuant to the general instructions he received from federal authorities to report “any attempts at witness intimidation or tampering with the jury,” “anything illegal,” or even “anything of interest,” Partin became the equivalent of a bugging device which moved with Hoffa wherever he went. Everything Partin saw or heard was reported to federal authorities, and much of it was ultimately the subject matter of his testimony in this case. For his services, he was well paid by the Government, both through devious and secret support payments to his wife and, it may be inferred, by executed promises not to pursue the indictments under which he was charged at the time he became an informer.

This type of informer and the uses to which he was put in this case evidence a serious potential for undermining the integrity of the truthfinding process in the federal courts. Given the incentives and background of Partin, no conviction should be allowed to stand when based heavily on his testimony. And that is exactly the quicksand upon which these convictions rest, because, without Partin, who was the principal government witness, there would probably have been no convictions here. Thus, although petitioners make their main arguments on constitutional grounds and raise serious Fourth and Sixth Amendment questions, it should not even be necessary for the Court to reach those questions. For the affront to the quality and fairness of federal law enforcement which this case presents is sufficient to require an exercise of our supervisory powers. As we said in ordering a new trial in Mesarosh v. United States,352 U. S. 1, 352 U. S. 14 (1956), a federal case involving the testimony of an unsavory informer who, the Government admitted, had committed perjury in other cases:

“This is a federal criminal case, and this Court has supervisory jurisdiction over the proceedings of the federal courts. If it has any duty to perform in this regard, it is to see that the waters of justice are not polluted. Pollution having taken place here, the condition should be remedied at the earliest opportunity.”

“* * * *”

“The government of a strong and free nation does not need convictions based upon such testimony. It cannot afford to abide with them.”

See also McNabb v. United States, 318 U. S. 332, 318 U. S. 341 (1943).

I do not say that the Government may never use as a witness a person of dubious or even bad character. In performing its duty to prosecute crime, the Government must take the witnesses as it finds them. They may

be persons of good, bad, or doubtful credibility, but their testimony may be the only way to establish the facts, leaving it to the jury to determine their credibility. In this case, however, we have a totally different situation. Here, the Government reaches into the jailhouse to employ a man who was himself facing indictments far more serious (and later including one for perjury) than the one confronting the man against whom he offered to inform. It employed him not for the purpose of testifying to something that had already happened, but rather for the purpose of infiltration to see if crimes would in the future be committed. The Government, in its zeal, even assisted him in gaining a position from which he could be a witness to the confidential relationship of attorney and client engaged in the preparation of a criminal defense. And, for the dubious evidence thus obtained, the Government paid an enormous price. Certainly if a criminal defendant insinuated his informer into the prosecution’s camp in this manner, he would be guilty of obstructing justice. I cannot agree that what happened in this case is in keeping with the standards of justice in our federal system, and I must, therefore, dissent.

The recording was not used here as a means to avoid calling the informer to testify. As I noted in my opinion concurring in the result in Lopez (373 U.S. at 373 U. S. 441), I would not sanction the use of a secretly made recording other than for the purposes of corroborating the testimony of a witness who can give first-hand testimony concerning the recorded conversations and who is made available for cross-examination.

One Sydney Simpson, who was Partin’s cellmate at the time the latter first contacted federal agents to discuss Hoffa, has testified by affidavit as follows:

“Sometime in September, 1962, I was transferred from the Donaldsonville Parish Jail to the Baton Rouge Parish Jail. I was placed in a cell with Partin. For the first few days, Partin acted sort of brave. Then, when it was clear that he was not going to get out in a hurry, he became more excited and nervous. After I had been in the same cell with Partin for about three days, Partin said, ‘I know a way to get out of here. They want Hoffa more than they want me.’ Partin told me that he was going to get one of the deputies to get Bill Daniels. Bill Daniels is an officer in the State of Louisiana. Partin said he wanted to talk to Daniels about Hoffa. Partin said that he was going to talk to Captain Edwards and ask him to get Daniels. A deputy, whose name is not known to me, came and took Partin from the cell. Partin remained away for several hours.”

“A few days later, Partin was released from the jail. From the day when I first saw the deputy until the date when Partin was released, Partin was out of the cell most of the day and sometimes part of the night. On one occasion, Partin returned to the cell and said, ‘It will take a few more days and we will have things straightened out, but don’t worry.’ Partin was taken in and out of the cell frequently each day. Partin told me during this time that he was working with Daniels and the FBI to frame Hoffa. On one occasion, I asked Partin if he knew enough about Hoffa to be of any help to Daniels and the FBI, and Partin said, ‘It doesn’t make any difference. If I don’t know it, I can fix it up.'”

“While we were in the cell, I asked Partin why he was doing this to Hoffa. Partin replied: ‘What difference does it make? I ‘m thinking about myself. Aren’t you thinking about yourself? I don’t give a damn about Hoffa. . . .'”

Mamma Jean began writing her memoir as a letter to us a few days before she died. She began, “To my children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren,” and she proceeded to tell us how she was fooled by Big Daddy. She agreed with Hoffa – most people thought he was handsome and charming – and said that over time you only remember the good parts.

She passed away before finishing her memoir. I called Aunt Janice and Uncle Keith, and listened to their versions. Of course, I had my version. And I had Uncle Doug’s autobiography. He was with Big Daddy when they were kids, stealing guns and pimping in Woodville Mississippi.

And, of course, there were the movies, but none of us had seen them. None of them were completely truthful, because, until now, no one put the whole story together. No one had assembled all the pieces. No one had asked his family what happened, and what we knew about Ed Partin.

This is my version of our part in his story.

Big Daddy and mamma jean

Edward Grady Partin’s father, Grady Partin, was a drunkard in Woodville Mississippi. He spent each week’s paycheck at the speakeasy bar, just like most men who worked at the sawmill. They drank homemade hooch that hadn’t given anyone they knew drop-foot disease yet, like most men in the deep south during prohibition.

Ed Partin had been born during prohibition, in 1924, when it was illegal to sell alcohol. Most men in town found ways to buy alcohol. There were a lot of drunkards in Woodville.

His family lived on a street of shotgun houses that radiated from Woodville’e sawmill. The fronts of their homes were only as wide as a small bedroom, and the rooms were in a straight line, making long rectangular houses that could be packed tightly along streets that had no public transportation and no personal cars. A shotgun fired through the front door would send pellets through the house and out the back door without hitting anything inside.

Families could walk to work in Woodville. On summer weekends, everyone sat on their porches with their doors open. Sometimes, an ocean breeze would blow through their homes and blow out the hot and humid air that settled in homes. This was before air conditioning, and people didn’t know any other way. It was nice to sit on your porch back then, and keep the doors open in to let in a breeze.

The only photo of Grady Partin was taken of him in a rocking chair on their porch, with their door open. He was sipping a glass of homemade hooch. He chose not to work, and no one was surprised when he ran out on Grandma and her three boys. They never heard from him again, and I don’t know if he ever got foot-drop disease.

Grandma didn’t have a way to earn money, other than sewing and selling quilts. People don’t buy many quilts – one is usually enough per bed, especially in the hot south. She watched her big boys grow taller and thinner.

Edward was the oldest man in his family. He had just turned 18. There wasn’t honest work available, and his momma and brothers were hungry. That’s when he stole all of the guns in Woodville. He had his little brother, Doug, help him.

Ed led Doug to the roof of the Sears Roebuck and Company department store, and showed him a hole in the roof Ed had either discovered or created. Doug was 12, and didn’t remember all of the details. The store was closed. Most people in town were at church or at the speakeasy.

He tied a rope around his little brother’s waist and lowered him inside. Doug walked to the hunting section and gathered as many rifles and shotguns as he could hold in his 12 year old arms. Ed pulled him up, and repeated they the process until they had lifted all of the guns in Woodville.

They piled the guns in their bedroom. All three boys shared a room, and Don wanted no part in their stealing. He would’t lie if asked, but he wouldn’t offer information. He wasn’t a snitch. He told them their momma had raised them better than that. Ed said he was the man of the house, and that he took care of his family.

The boys took all the guns they could transport at once to New Orleans Louisiana, an hour from Woodville. They drove in a car Ed somehow obtained, and found men who bought their guns without asking how two teenage boys had a car load of guns.

The family ate well for a few weeks. They bought motorcycles, and had the time of their life, zooming back and forth along Main Street and across the bridge that connected Mississippi to Louisiana.

The sherif may have suspected something when they zoomed by on new motorcycles after the only department store in town was robbed. They were arrested, and the sherif found guns in their shared bedroom.

Doug was too young for jail or the military, but Ed was given a choice: go to jail, or join the marines.

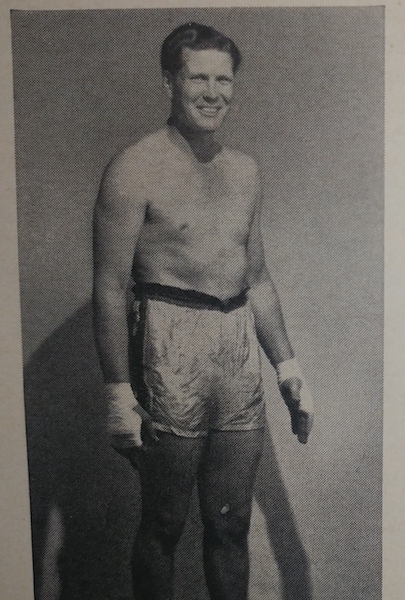

America needed soldiers to fight in the second World War, and food in jails cost just as much as beans and bullets on a battlefield. Big Ed listened to the judge. He read his contract to get out of jail, and he agreed to join the marines. He enlisted, and barely had time to join the recreational boxing team before he punched an officer. He returned home a few weeks after leaving, a dishonorably discharged marine and a free man. He had agreed to enlist, not to remain.

Ed boxed, and would fight anyone. He was a big man. Our family called him Big Daddy. He always had a knack for getting out of jail, but I think his knack was bigger. Somehow, he never had a boss, or had someone tell him what to do. No father, no boss, no leader. Big Daddy smiled when Bobby Kennedy got him out of jail.

Grandma loved everyone. She wasn’t religious, but she practiced forgiveness, and accepted how things were. That’s how you stay happy, she’d say. Forgive, and accept. “You don’t blame no one but yourself for your life,” she said. “You make mistakes and you try not to do them no more.”

“Edward’s daddy was no good,” she said.

She married a teetotaler named Arthur Foster. “He didn’t drink, and he didn’t smoke,” she told me. “He was good to me, and to my chil’rin. That’s all you can ever ask of someone.”

They bore Sandra Foster. Ed knew his momma was going to fine, and he and his brothers didn’t need a father. He focused on his self.

Big Daddy took over the sawmill labor union, and began collecting dues from workers. He negotiated safer working conditions and better hours for the sawmill workers, and they felt it was worth paying him a percentage of their paychecks.

Work was increasing because war stimulates the economy, and military barracks and weapons factories needed lumber. Everyone attributed their success to the work Bid Daddy did behind the scenes, getting work for them to do at the sawmill. To them, he could do no wrong.

He noticed that trucks delivering trees to the sawmill were paid twice, once for delivering trees, and once for carrying away cut lumber, boards ready for construction, and sawdust for paper mills. Big Daddy took over their fledgling labor union, called teamsters, named the old wagons that drove teams of horses to deliver trees, and take away lumber.

He led two unions, and was paid three times for every piece of wood delivered, cut, and removed. He provided for his family with the money he earned; he said his mother would never want for anything again.

Ed loved his momma and family, and did bad things. He was arrested for raping a woman in his early 20’s. She was a young lady who lived in town. I don’t know more about her, or her family, and I wish them peace.

During his trial, Bid Daddy smiled at the jury. For a judge to sentence him to prison, the jury had to unanimously vote that he was guilty of rape. The evidence was strong. All except one juror voted guilty. One white male said he wouldn’t vote guilty, because “ain’t no white man deserve to go to jail for nothin’ he done to a nigger.”

Big Daddy understood how juries worked. He felt he was unstoppable in Woodville, and that it was time to settle down and start a family. He was 26 years old when he met my grandmother. Norma Jean was a strikingly beautiful 18 year old redhead, with dark brown eyes that were almost black.

We called her Mamma Jean. She was from Spring Hill, Louisiana, and was visiting relatives in Woodville for a week, and she said she loved three things: Family, Jesus, and Seafood.

“My first suitor in Woodville didn’t like catfish, so I ended that,” she said, and nodded as if anything else was self explanatory.

“Big Daddy came over for dinner at Aunt Mildred’s house, and he asked for second and third helpings of fried catfish. He was so sweet and handsome.” She paused again and smiled, just for a moment. “He didn’t drink or smoke. He played nice with my nieces and nephews, and said he was a Christian man. He was charming. And he had a good job.”

Mamma Jean paused, and closed her eyes to see if she could glimpse something new in her memories. She knew the devil could quote scripture, so she was not easily fooled. Big Daddy was charming, went to church, played well with kids, and liked catfish. She never saw something behind her closed eyes that would have changed what she did next.

“I found a telephone at one of the neighbor’s house, and called Momma and told her I met man who would make a good father. We were married six weeks later, and I moved to Woodville and started a family.”

Woodville became too small for their growing family. Big Daddy and Mamma Jean moved two hours away to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where he took over Local #5 of the national Teamsters union.

He began making money, sending some of the union dues to national headquarters, and growing local jobs around the port of Baton Rouge, a small capital city on the Mississippi River, 135 miles upriver from the city of New Orleans. It’s small downtown held the state capital and governor’s mansion. On the outskirts, near the airport and petrochemical factories, there was plenty of open homes, with big yards farther apart than the cramped shotgun houses Big Daddy had grown up in.

He bought his family a home, near the construction site of the Baton Rouge International Speedway. It brought a lot of jobs to Baton Rouge, and no one seemed to mind that it was built with materials Teamsters took from construction sites in other cities. Big Daddy was an owner, behind the scenes.

He was charged with embezzlement of union funds. The two key witnesses were found beaten. One died. The safe with evidence was found in a river. The charges were dropped.

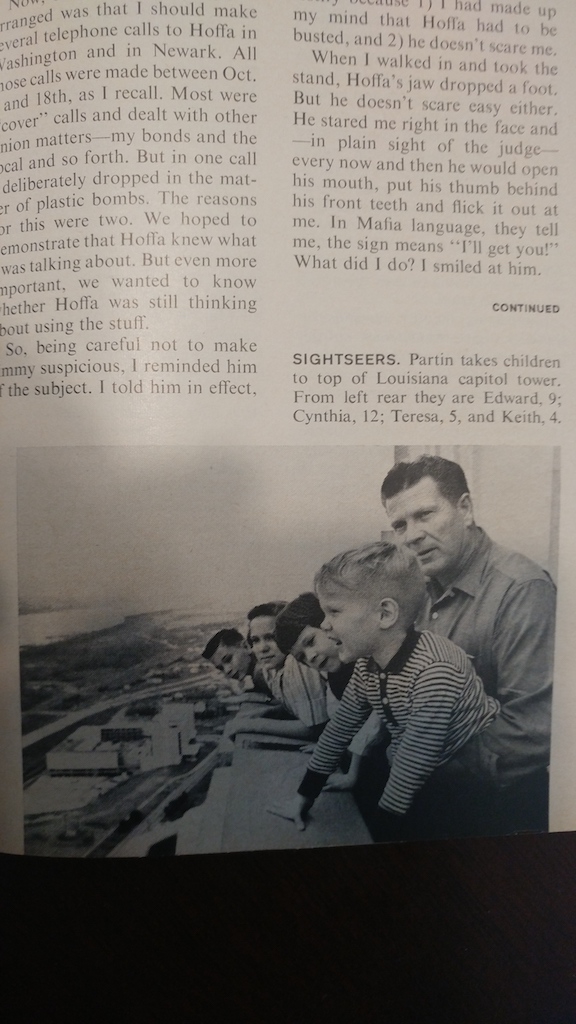

They had five children now: Janice, Cynthia, Theresa, Ed Junior, and little baby Keith. When Grandpa Foster died, he brought the rest of his family from Woodville to Baton Rouge, and bought Grandma Foster a house near the airport, but away from the flight path. She smiled and thanked him for giving her a yard to grow a garden and lots of space between her and her neighbors.

She had a back porch with a rocking chair, and could watch the railroad tracks shutting oil and plastics between Chemical Alley and the trucking center near the airport. Don went to college, and Doug joined his brother working for the Teamsters. For the first time, they accepted a salary from the national union headquarters.

Local #5 was already under the leadership of James “Jimmy” Hoffa, who was influencing local unions to unite into a political force, a voice for the working class American male. He had 2.7 million Teamsters paying monthly dues in cash by the mid 1950’s, which created millions of dollars a month in piles of cash.

The Los Vegas mafia became involved. Hoffa lent them cash to build casinos, and they hired Teamsters to deliver construction materials, and guns and drugs and money. They negotiated with Cuba’s president, Fidel Castro.

Fidel sent goods to the ports of Miami, and New Orleans. The port of Baton Rouge had fewer government regulators, and was only a few stops up the Mississippi River, and was connected to Interstate 10, which trucks could drive 3,200 miles and end up on the west coast, passing Las Vegas on their way to Hollywood.

Hoffa was behind the scenes of Hollywood movies. He befriended actors, and obtained contracts for his Teamsters to haul filming equipment. He even gave them credit, showing the old Teamster logo at the end of film credits: two horses and a steering wheel.

Teamsters transported almost every product made or used in America. If Hoffa called a labor strike, he could shut down the U.S. economy. President Kennedy wanted him and organized crime neutralized. He asked his little brother, Attorney General Bobby Kennedy, to oversee taking down Jimmy Hoffa. The President had other things to focus on: the Vietnam War, putting a man on the moon, an embargo on Fidel Castro, stopping nuclear war, and Norma Jeanne Nortenson, better known as the Hollywood movie star, Marylin Monroe. She sang Happy Birthday Mr. President to John F. Kennedy while Jimmy Hoffa and Bobby Kennedy went to war.

Newspapers called their war “The Blood Feud.” Both men openly hated each other. Everyone in America knew about their Blood Feud.

Hoffa was not a large man – he was 5’7″ – but he surrounded himself by big men who could intimidate company managers, and defend against mafia strongmen or government agents. Big Daddy was one of Hoffa’s lieutenants.

In August of 1962, Hoffa and Big Daddy and at least one other Teamster plotted to assassinate Bobby Kennedy, the U.S. Attorney General. They detailed everything. At first, they discussed explosives. Big Daddy kept a house rented in Baton Rouge, full of dynamite. They talked of throwing a bomb. Their final talk was prophetically similar to how President John F. Kennedy was killed a year later, which is what alerted Bobby Kennedy to the Teamster’s probably involvement with Lee Harvey Oswald, the lone rifleman who shot and killed the president in Dallas Texas.

Hoffa, Big Daddy, and one other person had planned a lone rifleman, trained as a sniper, firing into a convertible car. It was to be in a southern city. The gunman had to be unconnected to the Teamsters.

Lee Harvey Oswald, had trained in the Baton Rouge Civil Air Force, near the airport by where I used to walk to Grandma Fosters. He trained under the name Harvey Lee. A law professor tracked him down from there, and reported that Big Daddy drove Lee Harvey Oswald to the New Orleans airport before Oswald assassinated President Kennedy.

We knew that Hoffa and Big Daddy were close associates of Audie Murphy, a War hero and expert rifle marksman. By the time he was visiting Big Daddy in Louisiana, he was aHollywood star who had built his reputation on being the most highly decorated combat soldier in America.

Murphy had earned every medal there was to earn in the United States Army. What he did to earn the Congressional Medal of Honor was portrayed in the movie, To Hell and Back. Those scenes were used in so many other films that people knew who Audie Murphy was without knowing his name. The film’s title told the same story we all knew, that young men had gone to hell and were back, trying to earn a living in peace time.

Audie was the young country boy from Texas. Hid dad had been a drunkard, too, and left him to take care of himself, also. He hunted and became an expert marksman, and lied about his age to join the army and fight Germans in second World War. He killed a lot of men, and saved a lot of lives.

He was bad at business, and was poor as he grew older. He declined offers to be a spokesperson for alcohol or cigarettes: he didn’t want to be a bad influence on children. He advocated against war: he had Battle Fatigue. We call that Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. He became addicted to sleeping pills to sleep, and amphetamines to not be tired. Big Daddy became addicted, too, but was good at business, behind the scenes.

No one knows why Auddie Murphy was friends with Hoffa and my grandfather.

There’s a lot to unpack in this story. Most people assume Lee Havey Oswald shot and killed President Kennedy, probably because of the 1964 Warren Report, but that was never proved, and the 1979 Congressional Assassination Committee determined that Hoffa, Marcello, and one other person were prime suspects; though that wasn’t released publicly until 1992. Coincidentally, Lee Harvey Oswald trained in the Baton Rouge Civil Air Force two miles from my grandfather’s mother’s house, my grandfather’s testimony sent Hoffa to prison, Marcello was a mafia boss an hour from our home, and my family was under federal protection as soon as my grandfather agreed to testify against Hoffa. I don’t know anything about that, but I know that when my grandfather died in 1990, when I was a 17 year old kid, a lot of history died with him. Coincidentally, his final words were identical to some of the final words of Jack Ruby, the man who shot Lee Harvey Oswald before his trial, and who was an associate of Hoffa. My story won’t provide conclusions, but it’s as truthful as I can recall, and may shed light on what happened and what we could do going forward to ensure a more peaceful and transparent society.

This is a work in progress…

Return to the Table of Contents.