Dumpstaphunk

“Partin was a big tough-looking man with an extensive criminal record as a youth. Hoffa misjudged the man and thought that because he was big and tough and had a criminal record and was out on bail and was from Louisiana, the home states of Carlos Marcello, the man must have been a guy who paints houses.”

Charles Brant and Frank “The Irishman” Sheeran in 2014’s“I Heard You Paint Houses,” a reference to a hitman who paints the walls of a house red with splattered blood.

I straddled my backpack on both shoulders and limped across the Plaza San Francisco de Asis towards a small bar and grill. It had double doors wide open so that live music flowed out of the bar and across the plaza, and the open doors attracted my attention more than the other venues circling the square plaza. I’ve been slightly claustrophobic – for lack of a better word – since 1983, and after a long flight I always felt cooped up. It had been a long day of transfers, and I was about to burst from pent up energy. Double wide doors opening to an outdoor plaza seemed like an acceptable compromise between being outdoors and wanting food and a drink; and it had a standup bar.

Sitting is one of the worst thing anyone can do for their body. At least five randomized, double blinded clinical trials with and a meta analysis of more than 850,000 people followed over fifteen years by independent research teams says so. I walked into a bar so that I wouldn’t become a statistic. As for why sitting is risky: a right angle bend increases lumbar disc pressure 120% due to muscles yanking on your spinous process to maintain static equilibrium, so every minute sitting is, to your spinal discs, an unrelenting pressure that squeezes out lubrication, cushioning, and nutrients. In normal activity, walking and moving, your discs pump and nutrients and toxins exchange via mechanical osmosis. Your disc isn’t innervated in the nucleus, so we don’t feel the pressure until our annulus is desiccated years later, and the outer innervated layer is relatively dry and itchy and painful. It’s too late to do anything by then, because the disc isn’t vascularized. Any healing potential is negligible. From nature’s standpoint, you’re a mammal beyond child rearing years, a redundant use of resources, and not worth the energy to heal. Getting old sucks; if you’re going to grab a beer at a bar, the least you can do for your body is stand, move, or dance.

Sitting also puts pressure against the back of your thighs and restricts blood flow, so toxins accumulate in your legs and you have less oxygen reaching your brain and your mental processing becomes sluggish. Most people don’t notice, and believe sitting is relaxing. People who sit for a living, like truck drivers and office workers, have the highest rates of low back pain and diabetes; with sluggish blood flow, your body doesn’t use sugars as nature intended, and diabetes develops. Nurse aides have back pain, too; not because they sit, but because they reach over to move patients and send spikes of forces many times normal load through uninervated nucleuses, and the long term consequence is similar to sitting, though without disproportionately high rates of diabetes, like truckers and sedentary office workers.

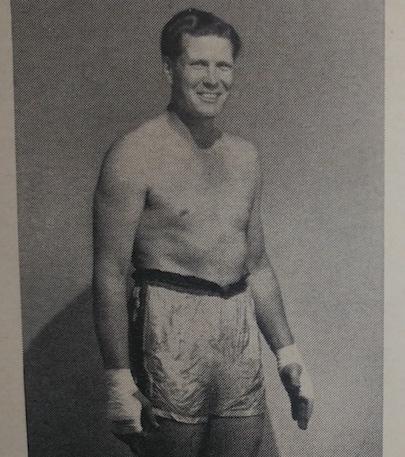

I chose to stand whenever I can, from my personal experience in a brief stent as an office engineer in 1999, and by remembering Big Daddy. He was released from prison five years early for declining health due to diabetes and an undisclosed heart condition. He had never sat around all day until he went to federal prison in 1980, and when I saw him in 1986 he was a deflated ballon of his former glory, soft and wrinkly, with just a hint of loft left. I was young and influential, and his change stuck in my mind.

Before sitting in prison, Big Daddy was always moving: helping his mother, Grandma Foster, around the house, fishing for largemouth bass in False River, hunting elk around Boulder and Flagstaff, boxing, beating people, tossing safes and bodies into rivers, and fending off small teams of low-level mob hitmen foolish enough to try their luck with nothing but a few knives and measly .38 specials. Sitting killed him when ten years of mafia hits could not. He died on March 11th, 1990, at age 66, from diseases secondary to sitting in prison for six years, and another three years of sitting around Grandma’s, barely lifting a finger to help out around the house, just sitting around all day, telling stories. I had been wanting to put those stories onto paper for thirty years, but never made the time.

I took a deep breath, exhaled slowly, straightened my posture, and walked into a bar. Happy hour was just beginning, and small bands were beginning to play to entice people inside after work. I walked past the band and stood at the bar a few feet from the young trumpet player farthest from the doors, and rested a foot on the brass rail below the bar.

I glanced around. Only about half the people were focused on the band, but even those chatting or laughing moved their bodies to the beat, channeling the band’s vibes or vice versa. Good music is a collaborative experience, and the vibe was right.

It was the perfect time for me to start happy hour, before the crowds arrived after work, and I could read at the bar. I should have been happy, immersed in my version of a slice of heaven, but I caught myself sighing again. My mind had drifted back to Wendy and my aching back, and my posture had slouched. I realized I wasn’t helping the room’s energy. Drastic measures would be necessary.

I straightened myself again and kept an eye up for the young light skinned bartender to notice. He saw me and began walking over. He had a wide smile and was wearing a casual Cuban styled button up short sleeve shirt, and sported a haircut that required a bit of extra effort every day before work and probably spoke softly to his female clientele. He was calm and confident, and leaned forward and said something I didn’t understand because of the band, but I assumed and shouted that I’d like a Hemingway daquiri and whatever seafood tapas were on special. I rotated my head to listen to what he said, but I couldn’t make out the words. I smiled enthusiastically at whatever he said, and gave a “thumbs up.” He smiled back, patted the counter to say he understood, and went to work.

He brought out the daquiri a few minutes later, but the food from the kitchen took about a song and a half longer. I sipped the drink on an empty stomach while I waited, and the placebo effect loosed my mind before the alcohol seeped into my brain. I finally began to unwind when it hit. I sighed a good type of sigh, not intentional, like when I decided to walk in, but the type of sigh that begins as a feeling of contentment and builds inside you and spills out through your lips as a sigh. The music sounded brighter, my thoughts had subsided, and my body joined the party. I was finally contributing to the room’s energy, in my own way.

I moved to the beat while inspecting what the bartender had delivered. The daily special was “calamar a la parilla,” grilled squid, cooked longer than ideal and toughened. I wasn’t complaining, I just liked nuances of seafood and was trying to enjoy myself. My eyes lit up, though, when I dipped a slice of squid in the side of mojo sauce, the first time I had ever had it. It was packed with roasted garlic and a tang from what was probably freshly squeezed orange juice, with just enough chili pepper heat to, as Chef Paul Prudhome of Commander’s Palace fame said, “wake up the taste buds and let them sense everything.” (Or something like that: it had been a ling time since I read his Louisiana Kitchen.)

I sliced the next bite of squid thinly and spread the creamy mojo on thickly to add some squish and compensate for tough calamar. I savored the next bite; the creamy mojo balanced the chewy better than I could have planned. I sighed again, a pleasant, content, relaxing sigh that rippled through my body and spoke more eloquently than the worry and discomfort, and all I could hear for a blissful moment was that mojo sauce and the rhythm of a six man band.

The Hemingway daquiri was strong and good and I ordered another. I sipped it gently to lower the liquid in the steeply angled margarita glass, one like Uncle Bob’s martini glasses that Auntie Lo would spill when she got sloshed; they were Wendy’s aunt and uncle first, and we’re creatures of habit. I never saw Uncle Bob spill a drop, and he’d quote some Asian philosophy from the Tao Te Ching that nothing can be added to a full cup, and it soon spills. His final words were in a combination of French and Latin, but in his last few weeks of life I recall him saying something in English, a paraphrase of the 81st chapter of the Tao Te Ching: more words mean less.

I sipped a bit more of my daquiri so I wouldn’t spill, and ostensibly danced to the band’s groove. I was actually stretching. After a few more sips, stretching became grooving. Cuban Funk seems to be made to move. The Lonely Planet said to look out for it in people’s daily lives; the driver who dropped me off at the plaza tapped his fingers on his steering wheel as we cruised into town. with Buena Vista Social Club blaring on his upgraded Bluetooth stereo. All around town, I saw people tapping their fingers to the beat of whatever music was nearby. People in the bar did the same, while simultaneously chatting with each other. A few wiggled whatever part of their body wasn’t stuck to a chair; some wiggled their butts, too. I couldn’t imagine a better first day of vacation, except for my worry and growing headache.

I had heard of the Buena Vista Social Club in America, if only because of the film, but there was more music worth discovering. I was anxious to listen to bands I hadn’t heard yet. I had a few ideas to prime the pump, because I’ve seen Cuba’s Cima Funk play with New Orleans’s Dumpstaphunk – with a ph – at Tipatinas, an old fruit stand turned hip music venue near the river’s Irish Chanel. Cima Funk opened with a few local musicians for Trombone Shorty, two of the Neville brothers, and a few members of Galactic, who had just purchased Tipatinas and was having a party to celebrate. Everyone there was enthusiastic about the Afro-Cuban music scene, which is like the Pope saying he digs another preacher’s sermon. A seed was planted in my mind at a late night show after a couple of local beers, and a week later I saw a few other Cuban and Carribbean bands two hours away, at Lafayette’s Festival International, and the seed sprouted. At the end of that trip, I saw a news blurb about the Obama entrepreneurship loophole and the sprout skyrocketed. I requested a visa and was approved, and a year later the tree bore fruit and I was standing in Havana, savoring a Hemmingway dacquiri, as if it were meant to be. Cristi called it synchronicity.

The band took a break, probably refreshing their energy before people began filtering in after work. I took advantage of the quiet to focus my thoughts, to seek out where my worry originated, hoping to either to justify it and focus on Wendy, or to quench it and focus on vacation. I opened my phone toched the synced Dropbox folder titled JipBook – I’m Jason Ian Partin – and read my 1976 custody report by Judge JJ Lottingger. Judge JJ had taken over my case when Judge Pugh alleggedly committed suicide in 1975, around the time Jimmy Hoffa disappeared from a Detroit parking lot. Unlike Pugh, JJ documented his thoughts about Wendy, similar to how Chief Justice Earl Warren documented his thoughts about Big Daddy.

This is a suit by Edward Partin, Jr., plaintiff, seeking a divorce from his wife, Wendy Rothdram Partin, defendant, after having lived separate and apart for more than one year following a judgment of separation from bed and board. Plaintiff also seeks custody of the minor child, Jason Ian Partin, and the defendant reconvened asking that she be granted the permanent care, custody and control of the minor child.

The Trial Court had previously, by ex parte order, awarded the temporary care, custody and control of the minor to Mr. and Mrs. James Ed White. Following trial on the merits, plaintiff was awarded a divorce as well as the permanent care, custody and control of the minor child, with the temporary physical custody of the minor child to remain with Mr. and Mrs. James Ed White. The defendant has appealed this judgment as it regards the custody of the child.

This couple was married when plaintiff was 17 and the defendant was 16 years of age. Nine months following the marriage, they gave birth to young Jason. While we are not concerned with the facts surrounding the separation and divorce, it was apparently one of incompatibility as defendant testified that at the age of 17 she found herself married to a man who did not love her and so she left. Her testimony was as follows:

“As I say I was emotionally upset. I was receiving little support from Edward. I was scared, very confused. I didn’t know exactly which way to turn. I felt I had no one to listen and help with the situation at hand.”

Several weeks later she returned and lived with her husband again. She found that the situation hadn’t changed, and felt she had to get away again. She heard of a man who wanted someone to share expenses on a trip to California, so she quit her job and with her last wages left with him. She testified that she had no sexual relations with this man, and plaintiff does not accuse her of such. Following this trip she returned to Baton Rouge still emotionally upset. Her husband was suing her for separation and told her he was going to take custody of Jason. She went to live with her aunt and uncle, got a full time job with Kelly Girls paying $512.00 per month.

In February, 1975, the defendant’s mother was injured in an accident and she moved in with her to care for her. In September, 1975, following the recuperation of the mother she returned to live with her aunt and uncle.

During these above periods of time, the minor child lived with Mr. and Mrs. White. The Whites came to regard Jason as their own and, although the separation judgment awarded custody to the plaintiff with reasonable visitation privileges to the defendant, the Whites decided the defendant-mother could only see the child two days a month and that she could never keep the child over night. The reason the defendant did not contest custody at the separation trial was because at the time she felt unable emotionally and financially to care for her son.

[Judge Lottinger wrote a paragraph of legal jargon here, citing the “double burden” placed on Wendy by the deceased Judge Pugh to go above and beyond what was typically necessary to regain custody.]

We note that the petition for separation was grounded on habitual intemperance, as well as abandonment of the husband and the minor child. There are no other grounds listed for the separation nor for custody. The petition for the separation and custody of the minor child was not contested by the defendant, and a default judgment was granted. Defendant testified in the instant proceedings that the reason she did not contest custody in the separation proceeding was that she was not financially or emotionally capable of caring for the minor, and that knowing the Whites were going to be caring for him, she knew he would be in good hands.

Though the petition for separation had as one of its allegations “habitual intemperance”, the plaintiff in the instant proceeding testified that he had never accused his wife of drinking, nor had he ever seen her drink.

[Judge Lottinger goes on to cite a few precent cases, verdicts from previous judges in higher courts used to justify his opinions, a detail that’s less important in Louisiana’s version of the Napoleonic code, but still useful to show one’s logic and suggest unbiased decisions.]

The welfare of the child is the main issue that the Court is concerned with. This issue is more important than any wishes or wants the parents may have. Fulco v. Fulco, 259 La. 1122, 254 So.2d 603 (1971), rehearing denied (1971). As a general rule, and in particular where children of young age are involved, preference is given to the mother in custody cases. This preference is very simply explained, the mother is normally better able to care for the child and look after the education, rearing, and training necessary. Estes v. Estes, 261 La. 20, 258 So.2d 857 (1972), rehearing denied (1972).

No argument is made that the mother is not now morally or emotionally fit to care for the child, or that the house in which she lives is not a proper place to rear a child. In fact, the Trial Judge admitted that it was a fine home.

The Trial Judge has not favored us with written reasons for judgment, however, we must conclude from various statements by the Trial Judge that appear in the record that he could find no fault with the defendant, nor was there anything wrong with the house in which she lived. It thus becomes apparent to this Court that the Trial Judge applied the “double burden” rule to the defendant. We have already ruled that the “double burden” rule does not apply in this situation, and thus, under the established jurisprudential rules, we can see no reason why the defendant-mother should not be granted the permanent care, custody and control of the minor child with reasonable visitation privileges granted to the father.

In consideration of our above opinion, there is no need to discuss the specification of error as to the ex parte granting of custody to the Whites.

Therefore, for the above and foregoing reasons, the judgment of the Trial Court is reversed, and IT IS ORDERED, ADJUDGED AND DECREED that the defendant-appellant, Wendy Rothdram Partin, be and she is hereby granted the permanent care, custody and control of the minor, Jason Ian Partin, and IT IS FURTHER ORDERED, ADJUDGED AND DECREED that this matter be and it is hereby remanded to the Trial Court for the purpose of fixing specific visitation privileges on behalf of plaintiff-appellee Edward Partin, Jr. All costs of the appeal are to be paid by plaintiff-appellee.

Wendy’s first home wasn’t fine: it was shithole infested with ants and cockroaches, a tiny two bedroom one bath ground floor unit with a narrow galley kitchen lined with peeling grease-stained wallpaper that once burst into flames when her skillet of bacon grease caught ignited. We had no air conditioning in Baton Rouge’s sweltering summers, but she resisted opening windows because we could smell rot wafting from the dumpster behind the cheap Chinese restaurant on Florida Boulevard. It swarmed with flies that would find a way inside our screen-less windows. The only upside I remembered was an endless supply of fortune cookies. I assume Judge Pugh, the trial judge, was being kind in his assessment, and I’d be surprised to learn he had actually committed suicide. I’ve always suspected Big Daddy had something to do with his 1975 death, and that JJ knew what he was doing when he stepped in and took over my case. Other than calling the shitty apartment a fine home, Judge Lottingger nailed our situation like Hoffa to a cross.

Lottingger was a respected judge with a 30 year tenure in the Louisiana legislature, working under three governors trying to rid the state of Big Daddy. Governor McKeithen, in particular, focused on Big Daddy like Bobby had focused on Hoffa, being quoted almost weekly in state newspapers saying things like, “I won’t let Edward Partin and his gangster, hoodlum Teamsters run this state!” Lottingger led the charge. McKeithen didn’t get Big Daddy’s endorsement on behalf of the Teamsters, and wasn’t reelected. I don’t know what prompted Lottingger to assume my case, but I can’t imagine him not reading the newspapers and realizing that my dad, Edward Partin Jr., was Big Daddy’s son. I don’t know why he didn’t mention it in my report; maybe he was being cautious.

What stood out reading my custody report that time was the offhand comment by JJ that my father said he never saw Wendy drink. It was true. She smoked prodigious amounts of pot with my father. He drank often and, by his own words with a chuckle implying he could go on and on, “dropped a whole lot of acid” when I was a baby, which is why he doesn’t remember a lot of the details accurately. But, Wendy only had an occasional light beer or glass of white wine when she was pregnant, and rarely, if ever, drank more than that until she was in her early 40’s, after my stepdad cheated on her and left with another family. She was still young and fit enough to date young men, the type of men who didn’t have kids or only had them on every other weekend, and liked to have a good time at LSU tailgate parties and the many bars around the gates of LSU. She fell into a habit.

I sighed, and tried to envision Wendy from before Mike left and in the years that followed: active, peppy, and hopeful, quick to join a group and chug back an extra glass of wine or two, an empty nester out to live a life without regrets.

It worked, in a way. I wanted to live a life without regrets, too, and I’d regret not focusing on my time in Cuba. I put my phone in the padded pocket on my backpack by the foot rail and waited for eye contact with the bartender. He had been busy running plates of food from the kitchen cutout to tables around the room. When he saw me, I smiled and held up Uncle Bob’s old gold money clip with a discrete credit card and neatly folded greenbacks; it was so old school that it spoke eloquently without me needing words.

“La cuenta, por favor,” I said when he approached, just to practice articulating Spanish words. He patted the counter, swung around, and returned a moment later with a bill and slid it across the bar to beside my empty glass. We chatted with the now quiet room, and he asked how I spoke Spanish so well. I chuckled to imply I was flattered or that it wasn’t a big deal, and said I lived in San Diego, on the border of Tijuana, and I couldn’t help but learn Spanish, “como la o’smosis.” He chuckled back at that, which told me I probably pronounced it correctly. I have a hard time with most accents and never quite lost my southern murmur, and my hearing is just off enough that I have to practice mouthing new words and getting feedback on how I did. Either I nailed “la o’smosis,” or the bartender, like most of us, simply chuckles when we chuckle and doesn’t correct strangers who say odd things.

The band began plaing again and I paid in U.S. Dollars and said, with eye contact and a nod of my head that could be heard over the band, “No necicitto cambio.” The bartender picked up the cash and smiled genuinely and waved as he said “Gracias! Buen viaje!” I put on my backpack and turned towards the door and began walking out. I dropped $5 bill folded in half into the band’s tip jar shaped like a spittoon, smiled, and clasped my hands and bowed a thank you to them without interrupting. At least, I hope it was a tip jar and not the band’s spittoon. I think it was a tip jar, because the trumpet who had played next to me locked eyes and nodded with his horn without missing a note.

I walked out the double doors, paused, and breathed in deeply. I caught a whiff of sea breeze, then sighed and smiled. I limped to my downtown casa particular, trying not to let my gimpy gait be noticeable, and realizing how tired I must be to not even walk straight. Anyone watching probably assumed it was the daiquiris, and they might have been right. Fortunately, I didn’t give a Pugh what anyone thought.

Go to Table of Contents