A Part in History, Part I

But then came the killing shot that was to nail me to the cross.

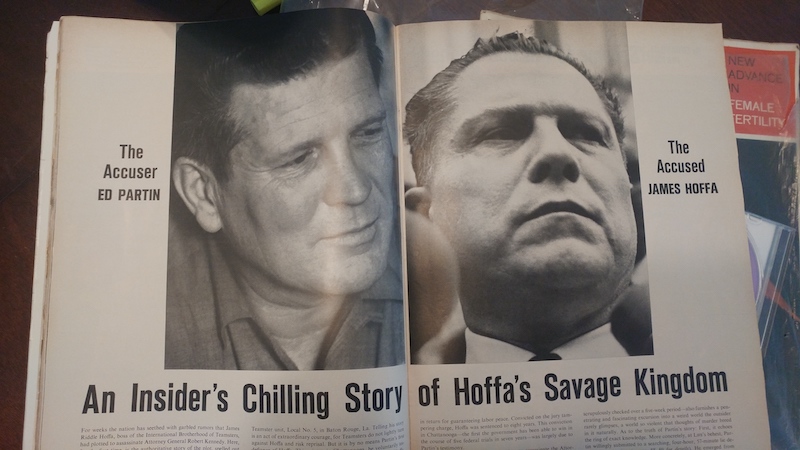

Edward Grady Partin.

And Life magazine once again was Robert Kenedy’s tool. He figured that, at long last, he was going to dust my ass and he wanted to set the public up to see what a great man he was in getting Hoffa.

Life quoted Walter Sheridan, head of the Get-Hoffa Squad, that Partin was virtually the all-American boy even though he had been in jail “because of a minor domestic problem.”

– Jimmy Hoffa in “Hoffa: The Real Story,” 19751

I’m Jason Partin. My father is Edward Grady Partin Junior, and my grandfather was Edward Grady Partin Senior, the Baton Rouge Teamster leader famous for infiltrating Jimmy Hoffa’s inner circle in 1962; his surprise testimony in 1964 sentenced Hoffa to eight years in prison. Everyone in Baton Rouge called my grandfather Big Daddy.

In 1983, Big Daddy was portrayed by the famous actor Brian Dennehy in the movie Blood Feud. Brian was less famous than my grandfather back then, but he was an up-and-coming star known for his “rugged good looks,” green-blue eyes, and charming smile. Producers felt that Brian could convince viewers that was the Ed Partin described in Hoffa’s second autobiography, published a few months before he vanished: “Edward Grady Partin was a big, rugged guy who could charm a snake off a rock.” That phrase, plus all of the national magazine photos and a few news blurbs where Big Daddy spoke in his drawl, made Brian a good fit.

(Coincidentally, Brian’s breakout role came that same year, when he starred alongside Sylvester Stalone in another film with blood in it’s name, “Rambo: First Blood.” Brian portrayed a Korean War veteran and the rugged small mountain-town sheriff who led the hunt for Rambo, a former special forces Vietnam veteran wandering America with PTSD. He would survive a scandal in which he stole valor, falsely claiming combat service in Vietnam to promote his tough image, and he would die in 2020 during the Covid-19 pandemic, a month before his final film debuted online, in which he ironically portrayed an aging Korean War veteran in modern times.)

In 2019, Big Daddy was portrayed by the burly actor Craig Vincent in Martin Scorcese’s opus about the Jimmy Hoffa and the American mafia, “The Irishman.” Scorsese raised $270 Million and hired a long list of Hollywood’s most famous actors know for gangster films, like Al Pacino, Robert DeNiro, Joe Pesci, and about a dozen others. Craig was chosen to portray Big Daddy because he had worked with Scorsese before, playing a big, brutal, thug in alongside Pacino and Pesci in the Las Vegas mobster film Casino. Scorsese based his film on a memoir by one of Big Daddy’s peers, Frank “The Irishman” Sheenan, a former WWII combat infantryman, Teamster leader, and mafia hitman who spent 13 years in prison before writing a memoir that says he killed Hoffa in 1975. Scorcese said he was not making a documentary, he was making a film for entertainment, so he centered the film around Frank, changed Big Daddy’s southern accent to match Craig’s northeastern Italian accent, and Big Daddy was renamed “Big Eddie” Partin for the film.

The Irishman sold out movie theaters the summer of 2019. It was picked up by Netflix when Covid-19 shuttered theaters worldwide, similar to how Brian Dennehy’s final film was released online because of the pandemic. The Irishman became available 24 hours a day practically everywhere on Earth and it set global streaming records; hundreds of millions of people all over the world got a small, fictionalized glimpse at Big Daddy’s part in history.

When Brian Dennehy died, some people made the connection between The Irishman and 1983’s Blood Feud, but by then fact and fiction had been blurred so much that probably only my family noticed the evolution of Big Daddy in media. With not much else to do at the beginning of the pandemic, I looked up my family history online.

There are many Jason Partin’s on the internet. One is my cousin, Big Daddy’s nephew, a former Zachary High School football star who went on to play for Mississippi State and now owns a physical therapy center in Baton Rouge; you can see that his smiling face on Lamar Advertising billboards along Baton Rouge’s I-10 interstate between New Orleans and the Mississippi River Bridge, and along I-110 billboards between Baton Rouge and Zachary. A few Jason Partin’s are criminals, but most are average people in towns across America. One is a mixed martial artist with a few Youtube videos; coincidentally, he looks like a younger version of me.

I’m the Jason Partin listed as an inventor on a handful of patents for medical implants that accelerate healing of broken bones, though some of the patents use my entire name, Jason Ian Partin. My cousin Jason and I have the same smile, which we inherited from Big Daddy’s father, Grady Partin, and when The Irishman came out I was the Jason Partin whose smiling face was on The University of San Diego Shiley-Marcos School of Engineering’s website, where I led a few engineering courses and ran the university’s innovation laboratory, named Donald’s Garage after Donald Shiley. That same photo was used on The University of California at San Diego’s website for their similarly named Basement, where I was an advisor for the Jacobs School of Engineering entrepreneurship program. No other photos of me were online. A few veteran forums mention my name in connection with the first Gulf war, where I served as a paratrooper with the 82nd Airborne, and for a handful of lesser known events in the 1990’s when I served on the quick-reaction force of presidents George Bush Senior and Bill Clinton. I’m also the Jason Partin listed by the Louisiana High School Athletic Association, www.LHSAA.org, as having won a silver medal in the 145 pound category of Baton Rouge’s city wrestling tournament in 1990.

Big Daddy died in 1990, my senior year of high school. His funeral was national news; but, to me, it was less important than what had just happened to my finger. Two weeks before half of Baton Rouge gathered for Big Daddy’s funeral, Hillary Clinton broke my left ring finger in the city final wrestling tournament. He broke it just below the middle knuckle, and it healed askew; to this day my two middle fingers are split like Dr. Spock’s salute when he wishes people to live long and prosper in the Star Trek series.

Hillary Rodham Clinton was first lady of Arkansas then; her husband, Bill Clinton, wouldn’t be elected president until 1992. The Hillary Clinton who broke my finger was the 145 pound, undefeated, three-time Louisiana state wrestling champion and captain of the Capital High School Lions. According to LHSAA.org, he would go on to win state again two weeks after winning the gold medal at city.

The joke about Hillary, though never to his face, was that he was like Sue in Johny Cash’s song, “A Boy Named Sue,” about a kid whose dad named him Sue so he’d learn to stand up against bullies and grow up tough and mean. But Hillary wasn’t mean. He was terse and scowled all the time, but he wasn’t mean and he wrestled fairly. I heard he was born in mid-October of 1971, a few days shy of being one year before I was born, and that he began kindergarten at age 5. He turned 6 a month later, and he was seven by the end of his kindergarten year. By the time we were seniors in high school, was a legal adult, able to vote in elections and to buy beer (possible because Louisiana was the last state to raise the legal age to 21).

He was 5’4″ and hadn’t grown taller since the tenth grade. His burly arms were proportionate, not gangly like a lot of growing teenagers. His thighs bulged with muscles, and his lats were a hands-width wider than his narrow waist. To fit into Capital High’s skin-tight maroon wrestling singlet, he had to wear a larger size than his lean stomach needed; it was taut across his chest but hung in loose folds around his waist.

Hillary had been shaving since the 10th grade. Everyone in the same weight class would stand side by side to weigh in at tournaments, where referees checked for clean-shaven faces. Unscrupulous wrestlers shaved a few days before a match to make their chins and arms abrasive, like course sandpaper, but Hillary shaved his face smooth each morning before competing. He kept his body hair natural, though, probably because his forearms were covered in Brillo pads like we used to scrub cast iron pots and his chest hair was already a mat of thorny spines that hurt like hell when he put all of his weight into pinning you.

It wasn’t the abrasiveness of his forearm hair that made an opponent turn their face. When Hillary cross-faced someone, he put every ounce of his short hairy body behind it, and the force would whip our faces away and allow him to spin behind for takedown and quickly flip you to your back. If you wore braces like I did my junior year, Hillary’s crossface would shred your lips and you’d choke on your own blood while he pinned you; I was fortunate that I had my braces removed before season began.

He defeated me seven times during the 1989-1990 season. I watched him compete against other wrestlers at every tournament, and I re-analyzed the one match of us recorded on Coach’s VCR machine massive television once every few weeks, hoping to learn weaknesses I could use to my advantage. There were none. He was undefeated, and the closest thing Hillary’s body ever came to staring at the ceiling was when he grasped wrestlers with his bear hug and arched his back to throw them over his body and to the mat. His throw would earn a full five point throw in summer freestyle tournaments, and in winter collegiate wrestling it almost always led to a pin. In those throws, he’d arch so steeply that the loose folds on his singlet would stretch out, and for a brief moment he seemed taller, as if he could defy physics to pin someone.

Hillary was the best bear hug thrower in all the southeast. At the Robert E. Lee Invintatrional, schools from as far away as Texas, Florida, and Oaklahoma came to Baton Rouge to compete in Lee High’s annual tournament. Mostly, those schools were there to face the Jesuit High Bluejays, a New Orleans institution with three levels of teams, a dedicated wrestling room with two mats, and banners laced around their ceiling with state title championships dating back to what seemed like the civil war era. But Hillary dominated even the Bluejay 145 pounder, and wrestlers from those other states would watch Hillary defy physics and rip through opponents on his way to another gold medal. He always won, and he never spoke with any of us before or after the tournaments. He always wore a scowl of fierce focus that discouraged visitors from approaching him, especially at the Robert E. Lee Invitational.

For three years, Hillary had been captain of the Capital High Lions, a 100% African American school located near the downtown state capital building. The surrounding homes were Capital neighborhood, once a nicer area near downtown and the port of Baton Rouge until the raised interstates of I-110 and I-110 created a ceiling over downtown that rumbled with 18 wheelers hauling chemicals from northern Baton Rouge and goods to and from the port of New Orleans that was linked to the rest of America via I-10. Like a lot of downtowns beginning in the late 1950’s, the interstates created a sinkhole of poverty around Capital High; white families moved away, and those who remained were overwhelmingly African American. Hillary, like all of the Lions, remained silent all weekend at the Robert E. Lee Invitational, a tournament named for the southern civil war general who fought to keep slavery only 125 years before our city tournament. Baton Rouge still has bullet holes in downtown buildings and cemeteries from what some teachers somewhat jokingly called The War of Northern Aggression.

The Baton Rouge City tournament brought in kids from all along the River Road because it was bigger than the actual regional tournament, which focused on schools of the same size instead of geographic proximity. My great-Grandma Foster, Big Daddy’s mother, remembered living next door to former slaves in their hometown of Woodville, Mississippi, which is only two hours upriver of Baton Rouge. Along the small roads connecting Woodville to Saint Francisville and Baton Rouge, majestic former plantation homes had been converted to Bed-and-Breakfasts that rented former slave quarters to tourists seeking quaint nostalgia, and the River Road connecting Baton Rouge to New Orleans was sprinkled with plantation homes turned into public gardens, restaurants, and event centers. Many of those small towns flourished with white families that fled downtown after the interstates were built. Though never discussed at the tournaments, it was possible that great-grandparents of some Louisiana wrestlers owned Hillary’s great-grandparents and made them work in the sugar cane fields that are still a backbone of southern Louisiana economy, and a staple of the Teamster trucks that rumble across I-I0 and rattle the gym rafters of Capital High School on their way across the Mississippi River Bridge.

It’s no wonder Hillary scowled.

I was the opposite. I usually wore a sly grin, though that’s more of a facial feature I inherited from Big Daddy; our cheekbones are high and pull up on the corners of our mouths, making it look like we’re smiling even when we’re not. But I was a genuinely happy kid, though I epitomized the awkward gangly years of a growing teenager. I was co-captain of the Belaire Bengals, and the youngest senior wrestling in Louisiana.

I was born on 05 October 1972 and began kindergarten in late August of 1977. I was only four years old when I began school, and I was always the youngest, smallest kid in class. Had I been born a few days later I would have been too young to start kindergarten and would have been pushed back a year. If that had happened, or if the cutoff date were shifted two days, I would have began my senior year at 17 instead of 16; I would have been 18 my senior year, able to vote and buy beer like Hillary (and, knowing what I know now, I would have been 5’11” and weighed around 190 lean pounds). Instead, I began my senior year as a 16 year old, 145 pound, 5’5″ tall, mid-pubescent kid with disproportionately long arms, wide hands, long knobby fingers, and scuba fins for feet.

My toes were bulbous monstrosities best kept hidden inside of tightly fitting size 11 wrestling shoes that looked like two submarines strapped to the bottoms of my legs with five sailors crammed together inside of each. My blue Belaire singlet was pulled taunt by my long torso. I had negligible underarm hair, and my pale face and shoulders were dotted with bright red pimples that stood out against the blue singlet. I had auburn hair that seemed to turn red with the increased sunlight of spring, and I kept it cut like a mullet, stopping just before my collar so I was still within state wrestling rules.

My voice had already changed, so at least I didn’t squeak when I talked, but my body was slow to catch up. I had never shaved and didn’t need to. The hair on my arms and legs was soft like the fur on a puppy. I never stripped naked to weigh in because I was embarrassed to have only a few scraggly black hairs hidden by my underwear.

My Achilles Heel, the weakness I couldn’t seem to overcome, was my lack of upper body strength when standing. I was vulnerable to throws and bear hugs by stronger opponents like Hillary. My saving grace was that I had quads thick with muscle from hiking the Ozark Mountains with my dad most summers in the early and mid ’80’s, carrying hefty backpacks full of horse and chicken manneur to his marijuana fields hidden far from roads, and I used my leg strength to shoot quickly in the first moments of a match.

My left ring finger had already been broken in my first wrestling match ever, when I was a mere 123 pounds and just after my dad was arrested during President Reagans’s war on drugs, but it was a small fracture and the doctor had just buddy-taped it to my middle finger; it had healed without being noticeable, but it created a stress-riser that would lead to another break when I wrestled Hillary at the Baton Rouge city tournament. Though not obvious unless someone stared at my left hand during a magic trick, I had a thick pink worm of a scar across the back of my first finger from a machete accident while helping my dad cut down male plants in 1983, and a sprinkling of white pinhole scars from handling barbed wire on his farm in 1985.

Those summers led me to have scarred hands and strong legs, and back in Baton Rouge for each school year I augmented my leg strength by running laps up and down the steps of the new state capital, a 34 story tower that was the country’s tallest state capital back then. To develop upper body strength, I did pushups every morning and throughout each day, sprawling my big hands and staring at that scar with every push. Before wrestling season, I ran cross-country track and worked out in the Belaire football weight room with a few other wrestlers.

My cross-face was strong. Not because I had upper body strength, but because when I pushed my fist across someone’s face my bulbous thumb knuckle caught and opponents nose. I was rarely taken down by a shot because my cross-face would deflect their face and halt their momentum. A good cross-face is essential defense if you don’t have strong arms yet; when you’re as strong Hillary Clinton, a cross-face is an unstoppable force, especially if you have Brillo pads all over your forearm.

I wrestled Hillary for the first time in mid November of 1989, when I was 140 pounds. Schools alternated hosting each other, and it worked out that the first and only time I visited Capital was for my first match of the 1989-1990 wresting season. After school on a Wednesday in early November, we crammed into the Belaire Bengal’s old blue Chevy passenger van used by all sports teams for field trips.

Our other co-captain, a 140 pounder named Jeremy Gann, a senior and returning silver medal winner at state who dropped down from 145 to avoid Hillary, was in the passenger seat next to Coach. I was the last one to load into the van, so I sat by the sliding side door and slammed it shut after confirming everyone was inside. We pulled out of Belaire’s gymnasium parking lot at 12121 Tams Drive and Coach slowly navigated out of Belaire subdivision and north turned onto Florida Boulevard towards Government Street and the new capital building. It was only 8 and a half miles, about how far I’d run after school during cross-country track practice each fall, but because of afternoon traffic and stoplights it took us around 20 minutes reach Capital High at 1000 North 23rd Street, just around the corner from the North Street church and a cemetery that still had tombstones riddled with bullet holes from when the north reached the state capital.

Jeremy jumped out, I opened the door, and the Bengals followed Jeremy and me in an informal and quiet herd. Coach, who had wrestled with the 1960 olympic team at 126 pounds and was a former marine from the Korean war period who never saw combat, followed to ensure no one was left behind.

The first I thing I saw when I approached Capital High’s gym was a hand-painted sign above the doorway, large gold letters against a black scroll that said Welcome to the Lion’s Den. Inside, they had laid out a faded purple and gold LSU wrestling mat donated after the team disbanded in 1979. The walls were painted maroon to match their singlets and warm-up hoodies, but the paint was so faded that the maroon was a close approximation of the faded purple mats, and most people didn’t realize the mats once belonged to America’s 4th ranked wrestling team, which was created and led by Coach after LSU recruited him in the 1960’s. When the 1979 Title IX law mandated equal numbers of male and female athletes in collegiate sports, LSU was one of around 100 wrestling programs disbanded to balance the match; that was when Coach donated the mats to fledgling programs around town and started Belaire’s team with only one wrestler, his youngest son, Craig Ketelsen, who became Belaire’s first state champion and graduated before I joined the team. Probably none of the Capital wrestlers knew that history, and the only reason I knew it was from overhearing other coaches talk about Coach Dale Ketelsen with admiration for starting so many Louisiana wrestling programs.

Capital’s gym had tufts of gray asbestos dangling from the rafters. The smell of mold was only barely hidden by the stench of sweat in a gym that mercilessly had no air conditioner, but no one there seemed to notice but us. Spectators in the stands wore the same black, green, and yellow colors of Capital’s murals. I didn’t know about Ethopia’s Lion of Juddah back then, and I thought the Lions were paying tribute to the colors of New Orlean’s Zulu parade. Eventually, I grew to think that the Lions were modeling the lion’s den from the Book of Daniel, because many wrestlers, myself included, had to shave off a pound or two before each match; like Daniel in the old testament, we fasted before facing a pack of lions.

Hillary led the pack. The Lions trotted onto the mat to warm up in a line that began with their 103 pounder and ended with their 275 pound heavyweight, like a line of purple hooded Russian Matryoska dolls, but with their 145 pounder placed in front. He wore his maroon hoodie low over forehead, and his dark face was hidden in the shadow.

The Lions remained eerily silent as they trotted onto the old LSU mat and jogged in a circle while stomping their feet in unison. Every team had its own warm-up ritual, but what stood out about Capital – besides the obvious racial difference – was the contrast of their vocal silence against the musical echo of their feet echoing in the gym. Their foot pattern mimicked a funky rhythm in the style of popular performers from the 70’s and 80’s, like James Brown or George Clinton, and as they circled they stomped the mat harder with their left foot on every forth step, like the 1 of a 4 step beat: ONE two three four, ONE two three four… The echos reverberated in the small enclosed room and we could feel the beat in our chests while we waited our turn to warm up.

The Lion’s spectators filled their relatively small set of worn wooden bleachers and stomped their feet on the one beat with Hillary and his team. They were mostly parents and relatives who rented cheap houses once built for the middle class after WWII, or in eight-unit, two story, rectangular brick apartments built with dark red bricks after I-10 was built. Regardless of wher they lived, the murals spoke to them and they radiated more pride than any suburb school I knew.

The bleachers shook and rattled every time spectators stomped on the beat. Loose screws would squeak, and flakes of paint would fall from the bleachers and land on the gym floor. No one seemed to notice the derelict stands other than visiting teams, who were more used to modern gyms without asbestos and quiet spectators. Even Belaire, which pleaded for more state funding and filled math and science teaching positions with untrained Teach For America volunteers, was Eden in comparison to Capital High. The only reason we had a new blue mat was because of Coach, who ran fund raisers and could buy expensive sports equipment wholesale through a small company he formed just for that purpose.

When the Lions finally stopped circling and sprawled into a tight circle, they landed with their faces close together on a silent cue none of us heard. The spectators calmed down and gave the team a moment of silence, and Hillary spoke so softly that I never heard what he told his team as they prepared for battle. For about two minutes, the den became a church; there’d be no stomping or squeaks from the stands, just an occasional cough or someone clearing their throat.

When it was Belaire’s turn, we pulled up our blue hoodies and trotted onto the mat silently and without being synced. Jermey led, I was second, and about 22 Bengals followed in whatever order worked out that day. About six Bengals were Red Shirts, a program Coach adopted from football that let kids not eligible for wrestling, because of grades or a disciplinary action agains them, still practice and walk onto the mat with the active team. I was one of them in the 10th grade. When a Red Shirt’s probation is lifted, they can challenge whichever weight class they wanted and fight for the right to wrestle first string. Until then, they warmed up with us just like any other Bengal.

We split into two groups like a flock of birds following two leaders. Every time different Bengals followed us in an evolving pattern that would make sense if you knew us; we naturally fell into zones of proximal development, small groups of three to five wrestlers who could all learn something from each other, and that would change every week and therefore our warm-up routine also changed every week. The zone of proximal development is a concept that came from the Soviet Union after WWII, when 30 Million Russians died and left millions of orphans to fend for themselves in massive gymnasiums without much supervision; toddlers naturally formed small groups, developing their own languages and patterns and mixing in and out of other groups to where give-and-take was balanced. Coach had a master’s in education theory and, because of his role to compete against the Soviet national wrestling team, was knowledgable about all things Russian; he had mentioned the zone of proximal development offhandedly, and though Jeremy and I didn’t understand how the Bengals flowed into groups we never questioned it. Even Jeremy and I would weave in and out of being in each other’s groups each week, naturally flowing into zones where we could both learn and teach within the same group.

We warmed up in the Lion’s Den by jogging onto the mats and circling for about two minutes, separating into groups of three to five, and practicing standard wrestling drills in slow and meticulous motions. Jeremy was such a better wrestler than I was at the beginning of season that he naturally formed a group with some of the other experienced Bengals. I was with Michael, our 135 pounder and a formidable third year wrestler, a couple of second year wrestlers, and two freshmen.

Each group methodically drilled single leg shots, doubles, stand ups, and sprawls, the building blocks of any great wrestler. Different zones practiced these moves with increasing levels of speed and intensity, but all with the intention of waking up muscles after a long day of sitting in classes. After warming up, we gathered behind Belaire’s corner of Capital’s mat. Both teams watched as I stepped onto the mat with Jeremy and we met Hillary in the center.

The referee spoke softly to us and reminded us to wrestle fairly. Jeremy and Hillary slapped hands in a modified handshake to show the spectators we would take the message back to our teams. Not used to two co-captains facing him, Hillary stared at both of us with stoic indifference. We returned to our corners and matches began at 103 pounds and proceeded up each weight class. I began warming up when the 129 pounders shook hands, because you never know how quickly matches can end and there was only the 135 and 140 pound match before mine. As an extreme case, if all matches lasted the entire six minutes I’d warm up for 18 minutes and step onto the mat with a hefty sheen of sweat.

Coincidentally, Hillary and I warmed up almost identically. Both of us took longer than most wrestlers, something I’d see again and again over the next few months. At Capital, though I wasn’t a threat, he still warmed up the same as if he were stepping onto the mat for state finals again. We began whipping our arms around our chests and stepping up and down as if we were climbing steps on the state capital or hiking up an Ozark mountain. Then we shook our heads and hands and feet faster, breathing in deeply and exhaling slowly. Hillary did jumping jacks and squat thrusts, I jumped a rope. Both of us were trying to slowly grow a thin sheen of sweat over our entire bodies, warming us up and beginning the match with the tiniest of advantages by having slippery legs.

When it came time to compete, Hillary took off his sweatshirt and donned his light brown hockey mask, like the one worn by Jason in the 1980’s Friday the 13th slasher films. It wasn’t an actual hockey mask, it was a wrestling mask for kids who competed with a broken nose. A hockey mask is rigid and covered in holes, but a wrestling mask is padded to be soft on the outside and has only two holes for eyes and one for the mouth, but it looked so much like a hockey mask that we all called it one. The analogy with Jason the slasher was apt because, like Hillary, he also never spoke and showed no mercy.

Only two other wrestlers in the state used a face mask. Hillary’s nose wasn’t broken like theirs was, but the mask protected him from cross-faces and, I suspect, added to his reputation as a silent killer on the mat. The only reason no one joked about me, whose name was Jason, facing Jason in a hockey mask was that everyone had called me Magik since the 10th grade and my real name was never used; even the tournament score boards would say Magik. But it stuck in my mind, and I almost wished people still called me Jason so I could make the joke instead of just chuckling inside and my natural smile gaining a twinkle in my eye; I had yet to face Hillary, so I was unaware that stepping on the mat with him was nothing to laugh about.

I donned the state mandated headgear and adjusted the straps to keep them pressed tightly against my ears and protect against cauliflower ear, that wrestling disease that comes from tight headlocks that destroys cartilage. I had a bit in my right ear that my mom had paid to have drained the previous spring, and my narrowed ear canal combined with padded headgear made the gym seem muffled. I barely understood the ref when he called us, but I knew the routine and what to expect. I trotted over and stood in the center and leaned forward to face Hillary. The whites around his dark brown eyes were barely visible in the shadows of his face mask. We slapped our right hands as a modified handshake to acknowledge we were ready.

The referee blew his whistle and I instantly shot a low single. Hillary sprawled, cross-faced the hell out of me, spun behind, drove my face into the mat, threw in a half-nelson, and turned me to my back before I realized how much it hurt. I could feel blood gathering in my nostrils, then I felt my shoulders touch the mat. The referee slapped the mat beside my face. Hillary pinned me in 22 seconds; it had taken me longer to adjust my headgear before the match.

We stood back up in the center, and the referee held Hillary’s hand up in the air. The applause from Capital’s bleachers was deafening, even with my padded headgear. I could feel the reverbations in my chest as they stomped their feet and hollered. Unlike most schools, which shout something like “Go Bengals!”, Capital’s fans sang their praise in unison, like a southern Baptist church raising the rafters with their voices. Hillary seemed unfazed. He strolled walked back to Capital’s corner and began prepping their 152 pounder for battle.

I returned to our corner and supported my team. Jeremy handed me a hand towel to wipe off sweat, mostly out of habit, though I still had a sheen from warming up. I used it to dap my nose, which was bleeding but not enough for anyone to notice.

I don’t recall the overall team score, but Capital won about 70% of the matches. Jeremy had pinned his opponent in the third round at 140 pounds before sitting back in our corner to be captain for my match. The other two notable wins were coincidentally the only two African Americans on Belaire’s team, our 275 pounder named Dana Miles and nicknamed Big D, a football linebacker who had to sweat off around 10 pounds to make weight after football season ended and wrestling season began; and our 135 pounder, Michael Jackson, who had no nickname because he was Michael Jackson, a captain in Belaire’s ROTC army program who had lost to Jeremy for Belaire’s 140 pound slot and had spent all week loosing five pounds and bumping out our original 135 pounder.

It was November, so days were short and we rode back to Belaire illuminated by street lights and traffic signals along Florida Boulevard. Everyone joked with each other and talked about what they’d do differently next time.

Unlike our drives to matches, the Bengals were chatty on the rides back. We usually talked about what happened on the mat and how we could improve. A year later, I’d be a paratrooper on President Bush’s quick reaction force, and our teams would do the same thing after every mission; we called it an After Action Review, and it’s an essential part of small team growth that I would use the rest of my life. Though Coach had been a marine, he never told the Bengals to review our actions. He never told us to do anything. For whatever reason, the Bengals naturally gathered and reflected on how we could improve after every dual meet, usually crossing zones of development to show moves or techniques to each other while everyone’s matches were fresh in our minds. At home matches, when we weren’t rushed to drive somewhere, Coach would waddle around the mat and give tips based on the needs of each group; when driving, he remained silent and focused on the road.

I listened to the After Action Review but sat silently that evening. I was nursing a sore nose with the blood-stained hand towel Jeremy had handed me after I lost; I was pinned so quickly that no one but me noticed that my nose was bleeding a little bit when I sat back down, and I was just beginning to process how much his cross-face had hurt. I ran my tongue across my front teeth and thought that at least I didn’t have to wear a mouth guard any more; that was one thing to be grateful for.

The difference between Hillary and me is obvious in hindsight. Coincidentally, in the mid 1980’s a research scientist noticed that professional hockey players in Canada were statistically likely to be born in spring. At first it seemed like astrology, but then researches realized that Canadian laws required being five years old by January 1st to begin practice; kids born the first few months of the year had an entire year advantage over kids born in the final few months.

Every year after, the kids who started sooner outperformed the ones who didn’t, and they placed higher and were therefore promoted faster and received better coaching, similar to how Hillary began kindergarten as the oldest kid in class and I began as the youngest. A year at four to five years old is a lifetime on an exponential growth scale, and the differences between two kids in the same class but eleven months apart grow and multiply each year.

That research study was practically unknown until brought to the world’s attention in 2008 by a book: “Outliers, the Story of Success.” It was written by Malcom Gladwell, a Canadian by birth who became a journalist for The Washington Post, writer for the New Yorker Magazine, author of several bestselling books, and popular TED speaker. He combined other research studies to paint a bigger picture in Outliers, and he pointed out that America didn’t have the sports laws as Canada, but the age cutoff for kindergarten creates a similar academic disparity: older kids in kindergarten begin with a 17% advantage on aptitude tests. Like how older hockey players are placed in more competitive groups and therefore grow stronger in a self-fulfilling prophesy, many older American students are grouped academically and their initial advantages grow over time, which, by definition, creates a class with disadvantages.

Gladwell quoted a social justice expert and called the phenomenon of advantages from birth and circumstance “The Mathew Effect,” after the New Testament’s book of Matthew, where Matthew wrote something like:

Whoever has, will be given more, and they will have an abundance; whoever does not have, even that will be taken from them.

Most of Gladwell’s books focused on topics about how little companies outmaneuver big ones, detailed in his book David and Goliath (named for the biblical and David who defeated a much larger foe, Goliath, using only a slingshot), and how individuals have brief moments of intuition that outperform teams of experts, detailed in his book Blink, as in the blink of an eye. In Outliers, Gladwell pointed to the unseen trends that shape success, like which month you were born; but, though dozens of interviews and case studies and research reports he showed how constant, persistent determination and practice seems to help anyone succeed. He interviewed people like Bill Gates and cited famous bands like The Beatles, and pointed to the 10,000 hour phenomenon that implies 10,000 hours of effort is necessary to overcome obstacles.

Most outliers, by Gladwell’s definition, are lucky. Even though putting in 10,000 hours of work is admirable, Bill Gates was still lucky because he had access to one of the world’s first computers to practice with. Before The Beatles were, as they said, “bigger than Jesus,” they played their first 10,000 hours in the windows of a red light district as background noise while men shopped; but, they were lucky to have the instruments and live where they could practice. Luck is the first and often most unseen way, Gladwell concluded, but it’s not the only way. Others create their success, but they are so rare that they wouldn’t fill a paragraph in his book.

If I had one thing in abundance, it was what my teammates called tenacity. I had lost all 13 matches of my 10th grade year before becoming a Red Shirt. My junior record was something like 75 wins to 50 losses, almost twice the number of matches most kids have because I kept getting beaten in semifinals and dropped down to the loser bracket to claw my way to third place finals; usually loosing there and getting an unrecognized fourth place. It was like having 10,000 hours of practice. Many chose to quit instead. Abundance means having enough to share, and it was tenacity, not talent, that led the Bengals to vote me both co-captain and most-improved the same year. Coach attributed my tenacity as an example that led so many Bengals to stick with wrestling even though Belaire was still a new program and being thrashed by schools like Jesuit, Catholic, Baton Rouge High, and Capital. The only other Belaire state champion other than Craig, Coach told us, was another kid named Jason who lost all of his matches his freshman year, but h stuck with the program and won state in 1985, his senior year, when Belaire only had enough wrestlers to fill half of the twelve weight classes.

It was dark when we arrived back at Belaire. Parents and carpools were waiting for most of the team under the gym parking lot lights. I said goodbye to the guys and straddled my 1981 Honda Ascot, a 500cc machine with a shaft drive that wouldn’t need maintenance for the rest of the season. I, on the other hand, was 0-1 and would need a lot of work over the next four months.

I watched everyone leave and then I sat there for a moment, remembering Hillary in his mask and wondering if it would help protect my nose. I sniffed, feeling the dried blood flakes rattle around the back of my nostrils. I was already in the army’s delayed entry program, so I believed I’d be going into the army after high school and that those battles would lead to real bloodshed, not the small red dabs on my hand towel that no one noticed. Though I didn’t know it yet, I’d look back on that van ride and dotting the blood from my nose soon after graduating high school, when I’d stare at a hand-painted sign on the Fort Benning Advanced Infantry School’s physical training field that said: “More sweat in training means less blood in combat.” I’d see that sign six days a week for five weeks, and chuckle to myself because nothing in the army was as challenging as wrestling Hillary Clinton, and the first nosebleed he gave me was my motivation to begin training harder than ever so that it wouldn’t happen again.

I stood under a light pole and pondered how I could stand up against that beast with only four months left of season. I decided that I’d start in the morning with an extra set of pushups and maybe an extra mile or two of running, then go from there. I saw myself turning into Sylvester Stallone in Rocky, running up and down the Baton Rouge state capital steps instead of Philadelphia’s capital steps and focused on wrestling Hillary Clinton instead of boxing Apollo Creed. Or, more like the high school senior in 1985’s Vision Quest who woke up early to jump rope and practically starved himself to death so he could drop 20 pounds and wrestle Shoot, Washington State’s three time undefeated state champion. Maybe I’d even be like Jason from the 1985 team, but winning state after only two years instead of four.

I took a deep breath and felt the unusually crisp Baton Rouge air that signaled the start of another wrestling season. I exhaled slowly until my lungs were empty and allowed myself to breathe normally until I wasn’t thinking about the day any more. It was time to go after a few breaths. I pulled on my full-face helmet, and pushed the ignition on my motorcycle. I watched my headlight illuminate the brick wall of Belaire’s gym, then I pulled out of the parking lot and onto Tams Drive and drove south on Florida Boulevard. I was home within five minutes.

I put my physics and calculus books by my alarm clock and adjusted the alarm to be twenty minutes earlier. I practiced a few card flourishes, concentrating on a one-handed pass with my left hand while spinning a card on the tip of my right forefinger to direct attention there instead of my left hand. I put down the cards and picked up four Kennedy half dollars and made them disappear and reappear to warm up, then I practiced on Kris Kenner’s Three Fly, the unobtainable Holy Grail of coin magic back then. Failing at Three Fly, I executed a perfect rendition of David Roth’s Hanging Coins, the Holy Grail of coin magic before Kris showed Three Fly to the world while on tour with David Copperfield in 1986, my first year of wrestling and the year my dad went to prison and that Big Daddy got out. I saw magic as an analogy for wrestling; nothing’s impossible, and last year’s unobtainable goal became this year’s reality.

Ending the night with the Hanging Coins set my mind at ease that it could happen again. I stacked the half dollars beside my cards and magic gizmos then laid down. My nose was clear and there was no hint of the blood from earlier; I breathed easily and was asleep a few minutes after putting my head on the pillow.

I slept so well I didn’t notice the lost twenty minutes when I woke up and began training with more focus than before my loss only twelve hours before. Without being told, I knew that more sweat in training would lead to less blood in matches against people with a brutal cross-face like Hillary’s.

Go to the Table of Contents

- From “Hoffa: The Real Story,” his second autobiography, published a few months before he vanished in 1975 ↩︎