Havana

But then came the killing shot that was to nail me to the cross.

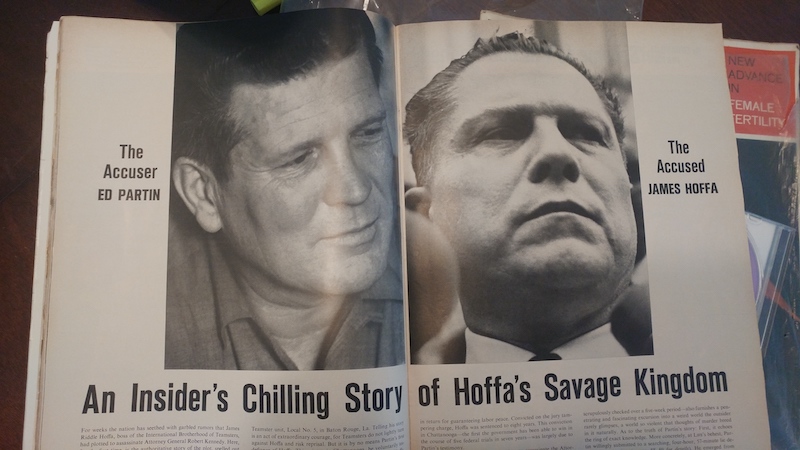

Edward Grady Partin.

And Life magazine once again was Robert Kenedy’s tool. He figured that, at long last, he was going to dust my ass and he wanted to set the public up to see what a great man he was in getting Hoffa.

Life quoted Walter Sheridan, head of the Get-Hoffa Squad, that Partin was virtually the all-American boy even though he had been in jail “because of a minor domestic problem.”

Jimmy Hoffa in “Hoffa: The Real Story,” 1975

I had just landed in Cuba on a 30 day entrepreneurship visa and was pondering my grandfather’s role in President Kennedy’s assassination, and suddenly I felt Wendy was planning to commit suicide; she wouldn’t, and I had no reason to suspect she would, but that was my first reaction when I listened to her voice mail while standing in the small Plaza de San Francisco de Asi, which I was told was one of only two places a gringo could catch public WiFi, even in 2019.

I was wearing a sun faded black backpack with short black scuba fins strapped to the outside, stretching and listening to voice mail by pressing an outdated iPhone 8 tightly against my left ear while poking my right forefinger into my other ear. I had been squished between different groups of big, chatty people on each leg, and I almost leaped from the plane before we rolled to a stop. As soon as we could take off seatbelts, I stood up and held my carry-on backpack and walked briskly from the plane to a row of private cars and asked for the closest place to buy a WiFi card and get public access.

My head hurt, my back ached, and I was wound up from sitting in confined spaces on a series of flights from San Diego to Havana. It was the first evening of what I planned to be a three month sabbatical: a month in Cuba thanks to Obama’s loophole to promote entrepreneurship (whatever that means), followed by two months of bouncing around Caribbean islands without an agenda. I had planned on jumping off the plane, checking messages from my circle once, and sending a burst that I had arrived safely and would be offline for at least a month. A few in and out of the circle knew how to contact me with something urgent; I was only half-heartedly listening to messages that were mostly wishing me safe travels.

I stretched and glanced at the bars, taking it all in and looking for outdoor seats or a at least a large window facing the plaza. When I recall this moment, I can still hear the din of downtown traffic as the workday ended, a hint of waves crashing on the melecon, and feel more than hear live music wafting from bars circling the small plaza, beaconing me to turn off my mind. But, when I heard Wendy’s voice, I slowly stood upright and stared at the phone in my hand. I almost called her right then. Gut instincts can be wrong, so I put in my earbuds and listened to her message again, looking for nuances that few, if any, other people would have noticed or understood.

“Hey Jason, it’s Wendy,” she began, followed by a pause.

“I know you’re going to Cuba, but I was hoping to speak with you about my will.”

Another pause.

“It’s not a big deal,” she said quickly and continued at a similar pace, clumping words so they almost sounded as one: “I’d just like to add Cindi as executor because you travel so much.”

She usually rushed words after a few glasses of wine, imagining no one would notice her sluggishness if she picked up the pace. She had called about her will several times over the past ten or fifteen years. Every time, she used the same brisk cadence, and it was always just before happy hour in my time zone.

Wendy was my mother, Wendy Anne Rothdram Partin, but she taught me to call her by her first name when I was a child in the Louisiana foster system and she was only 16 years old. When I was an infant, she abandoned me after my father, Edward Grady Partin Junior, left town with a group of his motorcycle friends to buy a literal ton of opioids in either Cuba or Jamaica. With no one there fore me, Judge Pugh of the East Baton Rouge Parish 19th Judicial District family court removed me from my parents custody and placed me with legal guardians. Wendy returned on her own, but was ashamed of her situation and taught me to call her by her first name, hoping people would assume I was her little brother when she took me around town once a month. She spent seven years fighting my dad and foster family to regain custody and I eventually lived with her, but old habits are hard to break; I still called my mother Wendy.

“And I thought…,” she said. I took two breaths in the pause… “It’s not important. Call me back when you can.”

There was another pause, and a sigh as subtle as the b in subtle. I doubt most people would have noticed.

“Tell Cristi I said hello, and I hope y’all are enjoying San Diego,” she said quickly.

Most people listening would say she forced her tone to seem upbeat.

“If I miss you,” she finished, “Have fun in Cuba and we’ll talk when you get back.”

I rewound the message – an archaic term for cassette answering machines that I still say in my head – and listened two more times. After she said, “And I thought…” I held my breath and leaned in to the silence. I may have heard something, but I wasn’t sure. I thought I heard a hint of “I…” arising, but fading without manifesting, as if she had caught herself before sharing more. I had never heard her do that before.

I sighed. Despite the smart phone in my hand, I rotated my left wrist and glanced at the 30 year old solar powered Seiko dive watch, modified to be a satellite pager. The technology was cutting edge back then. It hadn’t needed a battery changed or to be wound in three decades; the charge from an average day lasted six months, and I’ve been impressed by small solar cells ever since. The plastic parts oxidize and can break unexpectedly, so I replaced the thick black corrugated band before every sabbatical. I had replaced it at San Diego’s Just-in-Time on Sunday and landed in Havana on Tuesday. It was still on Pacific Standard Time. I did the math, and I could call Wendy back before she passed out that evening.

I sighed, hung up the phone, and rotated the side knob on my watch to adjust the time. I ignored the date, which cycled from 1 to 31, and had to either be adjusted or confirmed once a month. I never could remember how many days were in each month, especially if it were February in a leap year. I wouldn’t need to know the date for almost a month, unless I changed plans and flew to New Orleans, rented a car, and drove to Wendy’s home two hours upriver. If I stayed in Cuba, my iPhone would wake up four days before my visa ended and remind me that I had a plane to catch. 24 hours before my flight, my watch would vibrate, and it would vibrate every hour on the hour until I changed the date. I should have been sliding into vacation mode; instead, I was worried, debating buying a plane ticket to New Orleans.

I sighed again, and my gaze dropped form my phone to my two big feet. I avoid eye contact when something’s on my mind, just like Wendy.

I was her last surviving relative in America. We had a few distant cousins in Canada, and a 93 year old great-Aunt Mary, Granny’s sister (she would pass away in Richmond Hill during Covid-19, at age 94). I was the only person on Earth who knew Wendy’s history and mannerisms. She had only left Louisiana four times in thirty years: our scuba trip to Cancun with my stepdad in 1995, a drive to Chatanooga to visit a childhood friend in the early 2000’s, a flight to Canada to visit Aunt Mary in the mid 2000’s, and a flight to San Diego in 2008, just before the housing crash.

She developed a new, favorite joke on each trip. In San Diego, she began with: What’s the difference between the San Diego zoo, and the Baton Rouge zoo? She’d giggle, stumble over the punchline, back up, and eventually say: The San Diego cages have descriptions of the animals, the Baton Rouge zoo has recipes!

In Toronoto, it was: Do you know how Aunt Mary spells Canada? (Giggle, back up, start again) C-eh-N-eh-D-eh!

In Chatanooga, it was saying she finally got Hoffa’s pun for the title of Chapter 10 in his autobiograhy, “The Chatanooga Choo Choo,” the one about Big Daddy and Bobby Kennedy. (An old song is “The Chatanooga Choo Choo,” about a train, and Hoffa quipped that Bobby Kennedy used Big Daddy to railroad him at the 1964 Chatanooga trial.)

I can’t recall the one from Cancun, but it involved an iguana.

We ended our days early in San Diego, because she stayed in a Balboa Park historic hotel, walking distance from the zoo, and ashamed to be like Granny and Auntie Lo. Like them, Wendy was drunk by 3 and sloppy by 4 or 5, and that’s awkward for everyone. When sloshed, she’d start apologizing to me for things that happened long ago, though she rarely remembered what we said and would repeat herself the next night, just like Auntie Lo had. I never knew how to help her feel better about herself, other than to listen to her tell jokes about it.

Mike, my stepdad and an otherwise good man, overworked himself in a business venture, became depressed, cheated on Wendy, and moved to away with the woman and her three children; it was gossip at The Bluffs for years. Wendy fell into a slump and retired in 2010, after the housing crash stabilized, when homes were still a bargain and interest rates a trivial 2.4%. She had just inherited some money from our great-great Aunt Edith, an ancient Toronto socialite who had inherited Canada’s largest private art collection when, as an 80 year old spinster who retired on meager secretary savings, she married her boss of 45 years, Mr. Lang. When he passed a few years later, she went from virtual poverty to being one of Canada’s wealthiest women and followed by a few gossip columns. Aunt Edith loved to golf, and in her 90’s would travel the world’s best golf coarse and stop by Wendy and my stepdad’s venture, The Bluffs on Thompson Creek, a community centered around an Arnold Palmer designed golf course, to visit Wendy and talk about her travels. Her passing motivated Wendy to accept a generous early retirement package from Exxon in lieu of them firing her for “habitual intemperance” and “leaving work early” to golf and drink. She accepted the offer of around $275,000 cash, left work without thinking about it again, built her dream home, and planned to start golfing around the world. She proclaimed she’d live like Uncle Bob had, without regrets. After retiring, and while enjoying decorating her new house and landscaping her spacious private yard, she began to get drunk daily. It was celebratory at first, but it became habitual.

Wendy said she suffered 28 years in a job she hated, and that’s what led her to drink. She said it wasn’t worth waiting another two years for full retirement, now that she could add her inheritance from Aunt Edith to Granny’s, Uncle Bob’s, and Auntie Lo’s; and she still had her free, founders membership to The Bluffs gold course and country club, an otherwise extravagant $10,000 a year. To avoid a 10% early withdrawal penalty, she had to wait until she turned 64 to touch the accounts. As soon as she turned 64, she said, she would begin withdrawing from all her inherited IRA’s and traveling like Aunt Edith had. Not like I did. No offense to Cuba! she said. She wanted to see places like Paris and Dublin and stay in luxurious hotels with fluffy towels and room service, where she’d meet the next love of her life.

She was a Canadian citizen, because she procrastinated completing paperwork. She had lived in America for 59 years and kept her married name for 45 years, despite finalizing her divorce from my father two years after marrying him, because she didn’t want to change her driver’s license, social security card, or the IRA accounts. (I called Mike my stepdad, but they never married. Like Wendy, I had been embarrassed about our home situations, and in high school I lied to friends and said that Mike was married to my mom, and that she asked me to call her Wendy so we could be like friends.) To become a U.S. citizen required studying for a history and civics exam, and she never enjoyed studying. She said she didn’t need citizenship, that that her dogs never questioned her about anything, nor asked her to temper her drinking. She said I could learn a thing or two from them, and she was probably right.

Despite her reluctance to study, she was one of the wealthiest women in America. Granny had been a savy investor, and taught us that a dollar not taxed was a dollar earned. When she left Wendy’s dad in 1959 and she moved to Baton Rouge, she lived on her measly secretary salary but expounded happily on the concept of investing in her company’s retirement plan, and a personal retirement account she had read about in the paper.

Granny was a single mother with a little library beside her recliner, a reading lamp on her ashtray table, a small table of framed color photos of Wendy, me, and a few faded black and white photos of Grandpa Hicks in some of his hockey jerseys. Wendy visited family in Toronto she saw a community that loved their grandfathers and seemed to worship professional hockey players. When we spoke, she rarely didn’t start talking about Granny and Grandpa Hicks. Granny was Joyce Hicks Rothdram, and according to Wikipedia, her father was Harold “Hal” Hicks, a respected pro hockey player for several teams.

Harold Henry Hicks (December 10, 1900 — August 14, 1965) was a Canadian professional ice hockey player who played 90 games in the National Hockey League with the Montreal Maroons, Detroit Cougars, and Detroit Falcons between 1928 and 1931. The rest of his career, which lasted between 1917 and 1934, was spent in various minor leagues. He was born in Sillery, Quebec.

According to family lore, he was even more talented that Wikipedia alludes. I recall seeing Tononto Maple Leafs and Boston Bruins jerseys on Granny and Aunt Mary’s tables and walls, and I trust them more than Wikipedia. Grandpa Hicks retired from hockey and rose in ranks to be a senior manager of the Canadian rail system, and his 1965 obituary spoke highly of him and made newspapers nationally. From all accounts, our Canadian family was the equivalent of an all American family; besides Grandpa Hicks, none of them did anything to warrant a Wikipedia page. Wendy longed for a type of family like that, saying she skipped one to get me back from the Partin family, and she said that’s why she drank now.

Granny was a cool and quirky old bird, perpetually perky and positive; though adamant about right and wrong, and quick to call you or a stranger a dumbass if either did something only a dumbass would do. She was a tiny, wiry, dark haired Canadian lady with thick rimmed glasses and rarely without a cigarette gripped between two fingers. When it was her turn to drive the carpool to work once a week, she’d hold her cigarette between her lips, stick her left hand out the window, and give dumbass drivers the bird. Somehow, no one thought she was vulgar; it was if her cursing was an extension of her cheerfulness, a concise summary of a long conversation that most people would eventually have agreed with.

I’m unsure what happened to Wendy for Wendy to be prone to meloncoly when Granny wasn’t. Like Granny, she was petite, only 5’1″, but what most people would call athletic and voluptuous, wieghing about 20 pounds more than Granny, with long strawberry blonde hair and able to wear contacts instead of glasses. Both of us grew up seeing Granny remain cheerful despite work, the news, or that loud neighbor’s barking dog. She didn’t even mind the jet engines that roared over her home every 20 minutes, like clockwork, rattling the bottles in her licquor cabinet and shaking her tallboy of Scotch on the rocks so much that ice cubes stuck together tumbled apart and splashed into the Scotch like glaciers falling into the ocean; the bargain for her house was because it was directly under the Baton Rouge Airport flight path, and planes passed so closely we could see passenger’s faces peering down at us climbing trees in Granny’s spacious back yard. Every 20 minutes, we stopped talking for 20-30 seconds, until the roar dimmed and we could continue with whatever we were saying. Wendy remembers the jet engines; I remember the trees and bookshelf.

Granny kept her reading glasses parked atop her bookshelf, beside a photo of Grandpa Hicks on ice, holding a hockey stick, smiling and still with all his teeth, wearing an alleged Toronto Mapleleaf’s jersey. She wore bifocals at work, like the ones Ben Franklin invented, but she liked the feel of the lighter, plastic tortise-shell, half-moon reading glasses, and she appreciated the convenience of hanging them from her neck by their brown braided neck.

She was blind as a bat without her regular glasses, and after coming home from work, checking on Wendy’s homework, making dinner, and cleaning the kitchen; she liked to relax between book chapters or points to ponder, hang her reading glasses from her neck, and enjoy a smoke. In those blissful few minutes, she didn’t see anything else that needed to be cleaned, dusted, or dealt with.

Granny died at 64 from throat cancer after smoking at least a pack of Kents a day since her first Dupont paycheck, a splurge compared to her previous brand and, according to a paid advertisement by Kent, the preferred choice of teachers and scientists who smoke. The add ran in Life for years, and, to prove their statement, Kent showed a happy and handsome scientist smoking Kents. Granny, cigarette in fingers, said that add was bullshit, that anyone with half a brain could see smoking was harmful and addictive, and that any “dumb ass” could find a handful of teachers and scientists to say whatever they wanted them to say. Hell, Life even said your grandfather was an all-American hero; they print what people pay them to print. Don’t believe everything you read! Think for yourself!

Granny learned about investing by reposing in her recliner next to a liquor cabinet stocked with the best Scotch she could afford. Every night, she reposed with a tallboy filled with Scotch on the rocks and alternate between a books from one of five shelves. The top shelf was for her monthly Reader’s Digest subscription books. The second shelf was: Bullfinch’s Mythology, a dictionary, and a thesarusus; three investment books of authors I don’t recall, but with Warren-esque concepts; a stained first edition Joy of Cooking (it was a play on Granny’s name, and a good book), and, in 1986, she added Paul Prudhome’s Louisiana Kitchen. (He never graduated high school, Granny said, and look what happened! Paul was the world’s most celebrated chef, a local Cajun who jolfully headed Commanders Palace, was the first and only non-Frenchmen to be awarded France’s Chef of The Year, and had just cooked dinner for President Reagan and Prime Minister Gorbachev in a meal trying to create world peace. They failed; Granny said don’t let that stop you.)

The third shelf was and an assortment of classic fiction: at least a couple of Faulkner and Twain, one Tolstoy, and a coincidentally named James Joyce; my shelf was the Hardy Boy series, The Illustrated History of Magic by Christopher Milbourne and a handful of Karl Fuves’s “50 Tricks With…,” and some of the Nancy Drew series left from when Wendy managed the shelf. (Oddly, we had similar tastes, and were so close in age that, when she visited, we chatted about books a lot; she taught me my first magic trick, the one with a folded dollar bill.)

The bottom two shelves were an Encyclopedia Britanica, and Granny paid a yearly subscription for revisions. She sometimes glanced through Wendy and my books, rereading them to see if she learned anything new; Granny was pretty good at a few card tricks, and always something new up her sleeve to show me.

Despite choosing to smoke a pack or two of Kents a day, Granny invested wisely. The IRA’s Wendy inherited averaged 10.7% compounding interest and dividends over 30 years, greater than somewhere between 90% and 95% of all professionally managed funds, according to a few books I read. Wendy hadn’t tweaked Granny’s more than a smidgen here and there. Otherwise, Wendy inherited Granny’s original portfolio, which Uncle Bob had followed because he, like most people who knew her, trusted Granny’s research.

All of Wendy’s inherited IRA’s leaned towards Exxon, DuPont, Chevron, McDonald’s, IBM, GE, AT&T, and companies with plants or offices in Baton Rouge, New Orleans, and Houston. For almost thirty years each, both Wendy and Granny had allocated the maximum monthly amount possible in their company-sponsored retirement plans, around 10-17%, depending on congressional laws each year, and also contributed to individual plans in traditional IRA’s. (The Roth IRA wasn’t an option yet; when Wendy and I discussed the pros and cons, she kept a traditional plan. Currently, you can contribute $5,500 if you work for yourself, $17,500 if you work for someone else. Both increase by $1000 after you turn 65. Wendy, invoking Granny’s tone, said IRA limits were “a bullshit incentive to keep people working for someone else,” and she wouldn’t be a slave to Exxon with all those “assholes engineers.”) Granny retired from DuPont after 30 years, Wendy from Exxon-Mobil after 27 years. The interest of Wendy’s inheritance compounded for more than sixty years. If you do the math, that’s a lot of money by 2019.

The only advice Granny ever gave me – other than to not believe everything you read, think, don’t be a dumbass, and stop telegraphing your pass – was to understand compounding interest, and to obey the law. She adhered to all laws, from traffic signals to not killing a loud and opinionated neighbor, and she made sure Wendy understood that they were both guests in America. Granny had a work visa, and she and Wendy could be deported for a minor infarction, even one a seemingly benign as an unpaid library fine. I was born in the states, she would tell me, and I had nothing to worry about if I didn’t do anything foolish, and that big ears and feet were a sign of a handsome young man.

As of March of 2019 Wendy still hadn’t touched her IRA’s. She repeated Granny’s advice of avoiding 10% early retirement penalty on top of income taxes of around 27%. Until then, she was, admittedly, on a tight budget. Wendy had just begun receiving social security checks, and that’s barely enough to pay for her air conditioning bill, vet insurance, and wine. We had discussed Granny frequently over the past fifteen years, quoting her parting advice: everything’s a choice; have fun. I don’t understand why Wendy chose the way she did.

My eyebrows narrowed. My headache felt worse. I shouldn’t worry about Wendy, I thought to myself.

Wendy used her early retirement check from Exxon, around $275,000, and cash from Aunt Edith’s estate, to build her dream home while she lived off social security and a few dollars from her dog sitting gig. (The top half of her business card, printed on thick stock with raised ink, said: Wendy R. Partin, Dog Sitter. Food, walks, meds, and love. The bottom had her email address and cell phone number.) She lived in a luxurious, custom designed and built Acadian-style home in an affluent golf community near St. Francisville, a town of 1,300 people an hour upriver of Baton Rouge.

Other than other volunteers at the West Feliciana Parish Humane Society, she didn’t have much in common with people in town. The St. Francisville economy centered around a handful of old plantation event centers, bed-n-breakfasts (now mostly automated AirBnB’s), a few churches, and three prisons: one state, one federal, and one private, the infamous Angola and it’s annual prisoner rodeo. Angola prison was named after the nearby Angola plantation, which was named after the region of Africa from where they bought their slaves. Even in 2019, Angola prisoners are almost exclusively African American and, many are descended from slaves brought over by the plantations that drive St. Francisville’s tourism economy. A surprising number of tourists come into town on weekends to stay in slave quarters and tour nearby Oakley Plantation, The Oaks, Audobon (the famous painter and ornithologist had done most of his work at the now-named Audobon when he was employed there in the 1800’s), and a few lesser known homes that had been restored. But, that was never Wendy’s interest, other than the annual humane society fundraiser at one of the bigger plantations. She only went to town to eat at her favorite cafe, tour a few local artists galleries, or brainstorm with local craftsmen to make custom furniture for her home in a modern Acadian style and using old cypress or heartwood pine salvaged from ramshackle Cajun homesteads. She was a Canadian citizen, and our family coincidentally came from Prince Edward Island in Nova Scotia, where the Cajuns had fled 200 years ago, and she always felt a kindred spirit with the settlers who had fled Canada. She had never become an American citizen. Though she joked about not wanting to bother with the citizenship test, in the back of her mind she was always worried about being sent back to Canada, where it was too cold for her dogs, especially little threadbare Angel.

She didn’t have close friends in Saint Francisville, just cafe workers with cordial and phatic small talk, so she used to visit old high school friends from Glen Oaks in Baton Rouge once a week or so. The route “to town” followed Parish Highway 61, a straight road with wide shoulders, but long and dark and packed with massive and foreboding 18 wheeler trucks hauling chemicals and lumber towards I-110 and its connection to the cross-country I-10, the train depot near the airport, or to ferries docked in the port of Baton Rouge. She dodged 18 wheelers and passed ramshackle trailers and shacks of families still lingering from civil war days, a run down gas station with a hand written sign advertising used car batteries and fresh ‘coons, a nuclear power station, Fort Hudson State Park (the site of the longest civil war battle in America, a leisurely battle in dense, muggy, bug-infested woods that lasted 270-some-odd days), a row of chemical manufacturing plants and oil refineries with billowing smokestacks and names like Exxon Plastics, Mobile, DuPont, and American Oil and Gas, and eventually reached the northern terminus of Interstate 110. Twenty minutes south along I-110 she’d pass the Baton Rouge airport and the Glen Oaks subdivision, where Wendy and I grew up, and eventually arrive at LSU to walk around the lakes with her dogs and a girlfriend or two. Wendy had one of those friends as a roommate for a year, and I suspect there weren’t as many like minded friends in St. Francisville.

In 2018, she wrecked her car on the turn off Parish Highway 61 onto a narrow, curvy short cut. She was arrested for a DUI and spent thousands of dollars on Liam’s vet bills; the worst part, for her, was feeling horrified by her mug shot being published in The Advocate. Everyone in Baton Rouge saw it! Even as far away as her favorite cafe in St. Francisville saw it, because they kept a copy of the Advocate on tables for people to read over cups of Community Coffee or Tabasco-and-Bacon Bloody Mary’s. She began staying home more, sipping bottomless glasses sweet white wine instead of making cocktails or her famous Tabasco, Bacon, and Shrimp Bloody Mary.

There wasn’t a lot to do if stopped driving to town, and your back hurt and you couldn’t golf The Bluffs with your neighbors any more. The communities around Saint Francisville remained in niches, not mingling, and Wendy slipped into a loop centered around home-delivered dog food and cases of dry wine driven home from a discount liquor store after a quick brunch in her favorite Baton Rouge cafe. (Wendy had an affinity for catfish and shrimp po’boys, served with an orange juice mimosa or glass of sweet white wine; she drank dry wine for home, to reduce her sugar intake.) Her only break in routine was visiting the burgeoning West Feliciana humane society early in the mornings, playing with the dogs and giving them chew toys.

Once every few months, she’d find a dog on death row and take it home to nurture back to health, house train, and primp with cute purple and gold LSU hair ribbons for pet adoption events; no one but the society director knew that she also brought a bag of six McDonald’s breakfast sandwiches from the drive-thru and handed each to one of the Angola’s prisoner work-release men who cleaned the dog cages for 15 cents an hour, even in 2019. The sandwiches cost only 99 cents each, she said, and the humane society prisoners still had the same brown paper bags with sad-grey bolonga, hunter-orange processed cheese, served between two slices of Wonder white bread that the road-side workers and annual Angola prison rodeo fundraiser had for at least the thirty years we had been seeing them along Parish Highway 61.

Wendy had a soft heart for the less fortunate, and a reluctance to share her acts of kindness with people who, imagining they were being nice, pried into her private life, especially if they asked the dreaded question: Are you related to Ed Partin?

My biologic father had, in a story upon itself, gotten out of an Arkansas federal prison in 1986 after losing a battle in the war on drugs; passed his GED; earned honor graduate from the Univeristy of Arkansas with a dual degree in history and political science in only 3-1/2 years; earned a Juris Doctorate; was invited to speak to congress about legalizing flag burning; passed the Arkansas bar and, without attending school in Louisiana, passed the unique, Napoleonic-esque Louisiana bar exam; successfully sued the states of Arkansas and Louisiana to practice law as a convicted felon, a detail he had overlooked when planning his path; and moved back to Louisiana to become public defense attorney. He made news weekly, both for defending those who had no other defenders, and for frequent DUI’s and fines for contempt of court. He, in a remarkable coincidence, settled next door to Wendy’s coworker’s home in the town adjacent to Saint Francisville, the appropriately named Slaughter, Louisiana. When her coworker’s pried, they were just curious if Ed Partin were Wendy’s distant cousin or something. But, she reacted as if she had PTSD, and was known to snap at coworkers and tell them to mind their own business. Exxon’s early retirement offer was generous, and it freed her to do more of what she loved, like dropping off breakfast sandwiches with the harmless old African American men who cleaned the dog cages. She avoided Slaughter.

I shouldn’t worry about Wendy, but she was my mom.

I looked down at my big feet, took a deep breath and tried calling her back. As usual, her cell phone wasn’t getting reception, and she didn’t answer her land line (another archaic word in my head, used for some old phones and in the military, a wire hastily stretched between defense positions to use in lieu of radio or light signals that could be intercepted). I sent a text and an email letting her know I had already arrived in Cuba. I chuckled to lighten the tone, and said that that the cell reception in Havana was worse than at her place, and that I’d only be able to check messages when I came back to Havana every week or two, but to text or email me if it were important. I said I’d stay in Havana longer, if necessary, so we could schedule a time to speak. Coincidentally, I added with another forced chuckle, I was calling from a public square named after Saint Francis, the patron saint of kindness to animals, and I hoped that put a smile on her face. (She loved her dogs more than her wine, and they never asked her to seek help tempering the number of bottles she drank a day, like I did. If push turned into shove, she’d probably choose her dogs and wine over me; I kept that in mind when I sometimes mentioned her intemperance, or asked if she were still going to therapy.) I reiterated that I’d check messages when I could, and added a perfunctory “I love you” that, I hope, belied the irritation I felt.

I sighed again, and my gaze fell from my phone screen to my scuffy hiking shoes. I believe I saw, in a brief moment of realization, her situation and why she was calling.

It was almost April. She had left messages ruminating about Angel, the tiny, patchy, lap dog with LSU ribbons holding a few clumps of hair gracefully. She had nursed Angel back to health, and searched for a home that would love Angel as much as she deserved. Angel had died the April before, after 14 years with Wendy, and she was still sad and called me about it now and then. She may have called about Wendy’s Angel again, wondering if her IRA’s could go to help dogs like her. Or, she may have found a home for Liam, her big, goofy golden retriever. She has been searching for about three years to find a a home with kids to play with him as much as he deserved, and springtime was when most adoption fairs flourished, as if preparing for a summer of kids playing with dogs. If she found him a home, she’d cry over their empty spot on the living room floor for a month or two, just like she did every time she found a home for one of her dogs.

I usually listened to her slurred voice mails once, deleted it, and sent a text saying I wished her happiness. I meant it, but I typed or said it out of habit, usually because I was annoyed to be having the same conversation for almost fifteen years, ever since she began drinking daily.

I don’t know why I reacted differently that day in Havana. I figured I was tired. It had been a long day of sitting down between transfers and being cramped between too many chatty people. For years, my body has ached from sitting more than an hour or so, and my mind starts getting wound up as soon as I’m in a confined space. I’ve been slightly claustrophobic since 1983. I figured I was fatigued. Fatigue will make a coward out of anyone, Coach had warned. I had learned it can also make you imagine things or overreact to emotions. Knowing that, I decided to move forward with my vacation.

I sent a message to Cristi, saying I arrived safely and that the WiFi was less than I had expected, so I would be mostly offline. She had been used to gaps of contact ever since we were in middle school and missed each other for summer vacations, which transitioned to the first war and my service on America’s quick reaction force (we deployed with two hour notice and communication lockouts to prevent media discernment between real and simulated deployments used as training). Since then, I took off once a year or more for one to three month sabbaticals, and had developed a pattern with the people I called my people. In my message, I said everything was fine and loved her, paused, and enunciated that Wendy left a voice mail and I was concerned about her.

I didn’t mention the coincidence about Saint Francis because Cristi would have missed my bigger intention and locked on to such a strong coincidence, cheerfully expounding on synchronicity. I’d tell her about it later, after I got home. She collected memories and coincidences, and still had her copy of our matching fortune cookies from a Chinese restaurant off Florida Blvd in 1990, the one that said, “Friends long absent are coming back to you,” pressed between two pages of her worn first edition of The Artists Way.

Cristi was one of three people alive who knew my family history and had met both sides of my family. She has been my best friend since I was a little kid, the Jenny to my Forest. Her dad had worked for Big Daddy, but that’s no big deal: almost a third of Baton Rouge’s fathers had worked for Big Daddy, especially building the Pelican Speedway, and hauling equipment and actor’s trailers for all the Hollywood film sets they hauled around town. Cristi, in her favorite example of syncoicity, points to her 14 year-old self in the 1985 hit, “Everybody’s All American,” filmed in Baton Rouge and a huge event we all remember. Everyone in town dressed up in 1950’s garb to watch actors re-enact a famous football scene in one of our downtown stadiums; Baton Rouge is home of the LSU Tigers, and on game day you can see our purple and gold fans from space, so everyone got into filming Everybody’s All American, thanks to Big Daddy brining work to Baton Rouge. In the 80’s, films like Everybody’s All American, The Toy, and a few others were filmed in Baton Rouge, thanks to Big Daddy and the Teamsters. I wasn’t in Everybody’s All American, ironically, because I was with my dad in Arkansas, growing weed; I grew up being a secretive kid, and I cherish the few friends from Baton Rouge who knew the truth about my family.

I looked up, took out my earbuds, and sighed again, intentionally. I inhaled slowly and deeply, and exhaled just as slowly until my lungs completely emptied. I squeezed a puff more out, then inhaled again, but a bit less than before, and exhaled just as slowly. I began breathing naturally and glanced around the plaza to see if anyone was paying attention. There were a handful of people scattered here and there, most on their phones. A few were walking around, peering into the bars and chatting with their people about what they saw or heard inside, excited by the prospects. No one seemed to notice much.

I made a decision. I opened my Lonely Planet and called a couple of casa particulars I had circled on the plane ride from Fort Lauderdale. My entrepreneurship visa required not exchanging currency with any government owned business, like hotels, and I hadn’t bothered to plan ahead. I asked a few questions from each host until I confirmed which had a room with two doors. I learned one of the casas had a glass door that opened into a courtyard, and I told them I’d be there after dinner. I sent the burst message to my circle. (“Burst” was once an encrypted scramble between synchronized frequency-hopping radios in a single-integrated network, ground-and-airborne radio system, the most advanced communications technology known; now burst messages are accomplished by typing a list of names in the “bcc” line of a free email account.) I typed a quick gmail to two thirty-something eco-sports journalists, telling them I had arrived and would see them in Vinales in a week or so. I sent WhatsAp to a young illegal climbing guide in Vinales, similarly worded but limited by my rusty Spanish. I ere towards caution when I don’t know local lingo yet.

Under Cuba’s national health coverage, unnecessary and risky sports are illegal, and his father’s unregistered lodging could invite hardship to their family. The law wasn’t enforced, like American marijuana laws or President Clinton’s “don’t ask, don’t tell” military policies in 1992, but there was always a possibility that one law enforcement official with a bug up his ass could use an obscure law to confiscate a farmer’s land or to make an example out of a gringo or two. President George Bush Junior had personally been involved in a $14 Million pursuit of Tommy Chong, from the comedy duo Cheech and Chong, for helping his daughter start a glass pipe business that everyone had to call Chong’s Bongs; he was arrested in his pajamas at his California home by a federal task force one morning. He spent nine months in federal prison for what was legal in California but illegal federally, sharing a cell with The Wolf of Wall Street. That’s no joke. In Cuba, we’d be staying on the alleged guide’s family’s farm, the one they had let slip was being remodeled into a guest house for climbers. I lean heavily towards caution when other people are involved.

As a side gig, I was an alleged rock climbing guide in remote regions of off-the-beaten-path countries, like a fractal spiraling towards the last untouched place on Earth. I’m notoriously “hands off,” reticent about details, especially over the phone. Like Wendy, I’m allergic to paperwork, so I differ permits and insurance to assistants. Rock climbing’s not a big deal, but it’s still illegal in some countries with national healthcare. You never know who’s listening, or when a local law enforcement officer with a grudge against your nationality or race would arrest you for the most trivial of infarctions.

If that sounds paranoid, crazy, or szcizophrenic, you may be right. But, to put my caution in perspective, Jimmy Hoffa, the world’s most powerful labor leader and one of the wealthiest and most well known men in America not a Kennedy, went to prison in 1966 for a few words spoken to my grandfather. They were in a closed hotel room and guarded by Hoffa’s inner circle, and Hoffa uttered out a single sentence implying Big Daddy bribe a juror in the Test Fleet case against Hoffa. He timed his sentence with the motion of patting an envelope of cash in his back pocket, saying $20,000 should do it. They were standing beside a safe with stuffed envelops and other ways of influencing a jury. The room was swept for bugs by the best electronics goons money could buy, and Hoffa’s lawyers were the best money could buy who were willing to work for people like Hoffa, Marcello, Traficante, and all the mafia families nationally. He had a team of trusted brutes surrounding him all day, every day, and he told all of them, including the lawyers, that the Big Daddy was trustworthy. Hoffa slept well at night; he had, after all, avoided Booby and the FBI’s ridiculously funded and singularly focused Get-Hoffa task forces for more than a decade. Two years later, Big Daddy was the surprise witness who stood up and nailed Jimmy Hoffa to a cross; he was sentenced to eleven years in federal prison for jury tampering in the otherwise minor, state-level Test Fleet case, based solely on Big Daddy’s word.

Big Daddy was handsome and charming. Hoffa wrote in his autobiography that “Edward Grady Patin was a big, rugged guy who could could charm a snake off a rock.” When Big Daddy stood up in the courtroom, foreshadowed anonymously as Booby’s surprise witness, Hoffa, an otherwise stoic man in front of judges, gasped and exclaimed loudly enough for the entire courtroom to hear: “My God! It’s Partin!” The jurors in the cheap seats heard him loud and clear. Big Daddy’s smooth southern drawl quickly convinced a jury that the combined actions and words unequivocally suggested Hoffa asked him, Ed, to bribe them to throw the trial, to get this bullshit from Booby over with (Hoffa always called U.S. Attorney General Bobby Kennedy “Booby” or “that spoiled brat”). The image of Big Daddy in Hoffa’s hotel room, hearing a combination of words uttered while Hoffa patted his back pocket were enough for the jury, and no recorded evidence was necessary. The defense cross-examined Big Daddy for three days, each day hammering a nail deeper and deeper. As the prosecution said: everything Big Daddy said would happen, happened; he was a reliable witness.

The entire time Big Daddy testified he was sitting in the hot seat beside the judge, and Hoffa and his circle sent mafia hit signals to him, flicking their thumbs against their front teeth and other signals that hadn’t become Hollywood mob film fodder yet. Chucky O’Brien, Hoffa’s adopted son and a low-level runner for the mafia, glared at Big Daddy like a pit bull focusing on a rat. Only a couple of days before, Chucky had leaped across the crowd and tackled an assassin who walked into the courtroom bent on harming The Old Man, which is what he called his dad. Chucky took the bigger man’s weapon and pistol whipped him with it before he FBI agents, armed police, and armed courtroom bailiffs could pull Chucky off. It was that kind of trial. The police arrested the assassin – it was only a pellet gun – and Chucky was allowed to stay, earning a bit of respect from everyone who had witnessed the most recent spectacle in what was becoming a nationally publicized trial. According to witnesses, while all this was happening, Big Daddy just smiled and nodded, as if he had no worries in the world. He was in control, not Hoffa or the FBI, and he could have swatted Chucky away like a gnat. He was called Big Daddy for a reason. As the prosecution said, what Big Daddy said would happen, happened.

Hoffa’s defense team cross examined Big Daddy for three days. He quipped with them the entire journey, as if he were on a car ride with friends. The jury loved him, and they unanimously voted to believe Big Daddy more than Hoffa and his team of lawyers. After the 1964 trial, Big Daddy resumed running the Baton Rouge Teamsters and became a national celebrity for several years, propped up on media pedastles by Booby Kennedy and Walter Sheridan to showcase their star witness as Hoffa’s team appealed. Hoffa fought Big Daddy’s testimony all the way to the Supreme Court, a remarkable achievement in itself, with only a few cases out of dozens of thousands submitted being reviewed each year. Hoffa’s team of lawyers were the best money could buy, the same team that represented mafia families, like attorney Frank Ragano, “lawyer for the mob,” who represented all three primary suspects in the JFK Assasination Report: Jimmy Hoffa, New Orleans boss Carlos Marcello, and Miami boss and Cuban exile Santos Trafacante Junior.

Hoffa’s team and half the Teamster army spent two years investigating Big Daddy’s background, digging up skeletons across the country and presenting them in their case to have Big Daddy’s testimony thrown out. And, Hoffa’s lawyers, being lawyers, held up the constitution as if it were the bible when it suited them. They proclaimed that Big Daddy hadn’t been planted for one thing, that Booby’s boy violated the forth amendment by being the equivalent of a walking bugging device that recorded everything, without a plan or probable cause. And, they exclaimed, Booby violated the sixth amendment by having a witness jump up and scare the hell out of you. They raised valid points, and in 1966 their argument reached the United States supreme court doccet, overseen by Chief Justice Earl Warren, one of the most well known names on Earth after his Warren Report mistakenly proclaimed that Lee Harvey Oswald had acted alone when he shot and killed John F. Kennedy, and that Jack Ruby acted alone when he shot and killed Oswald two days later, who was in handcuffs at the Dallas police station.

They lost. The only one of nine judges to dissent against using Big Daddy’s testimony was Warren, a 40 year veteran of the court, having overseen landmark cases such as Roe vs Wade, Brown vs The Board of Education, and the case that gave us Miranda Rights; yet he didn’t have access to Hoover’s files. Warren had been chairman of a committee to investigate President Kenendy’s assassination; the committee was publicly known, expected at the time, and hand-selected by men like former vice president Lyndon B. Johnson and FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, both of whom knew Big Daddy. Hoover endorsed Big Daddy’s lie detector test in a 1964 Life magazine feature, the one that had focused on the Partin family and the newly appointed President Johnson family. Johnson’s daughter got the front page, but Aunt Janice’s beautiful smile and loving gaze rest squarely on Big Daddy’s face in the centerfold, and Big Daddy with my father, Kieth, Cynthia, and Theresa are sprinkled throughout, demonstrating what a good father he was; Mamma Jean’s absent. In that issue, the editors of Life – who had helped Warren and his committee – showcased to The World that the only witness to Hoffa’s crime was Big Daddy, a man who had probably stopped Hoffa’s plot to murder U.S. Attorney General Bobby Kennedy by tossing plastic explosives into his family’s home, possibly killing his wife and children in the process. Life told Earth that Baton Rouge Teamster leader Edward Grady Partin was an all-American hero.

Chief Justice Warren may not have read that issue of Life. He had this to say about Big Daddy in his notes of dissension, permanently attached to Hoffa vs The United States for posterity to ponder:

“Here, Edward Partin, a jailbird languishing in a Louisiana jail under indictments for such state and federal crimes as embezzlement, kidnapping, and manslaughter (and soon to be charged with perjury and assault), contacted federal authorities and told them he was willing to become, and would be useful as, an informer against Hoffa, who was then about to be tried in the Test Fleet case. A motive for his doing this is immediately apparent — namely, his strong desire to work his way out of jail and out of his various legal entanglements with the State and Federal Governments. And it is interesting to note that, if this was his motive, he has been uniquely successful in satisfying it. In the four years since he first volunteered to be an informer against Hoffa he has not been prosecuted on any of the serious federal charges for which he was at that time jailed, and the state charges have apparently vanished into thin air. Shortly after Partin made contact with the federal authorities and told them of his position in the Baton Rouge Local of the Teamsters Union and of his acquaintance with Hoffa, his bail was suddenly reduced from $50,000 to $5,000 and he was released from jail. He immediately telephoned Hoffa, who was then in New Jersey, and, by collaborating with a state law enforcement official, surreptitiously made a tape recording of the conversation. A copy of the recording was furnished to federal authorities. Again on a pretext of wanting to talk with Hoffa regarding Partin’s legal difficulties, Partin telephoned Hoffa a few weeks later and succeeded in making a date to meet in Nashville, where Hoffa and his attorneys were then preparing for the Test Fleet trial. Unknown to Hoffa, this call was also recorded, and again federal authorities were informed as to the details.“

Warren’s missive of dissent was lengthy, even for a missive. After a few more paragraphs of ranting about Big Daddy, Warren mentioned my grandmother, Norma Jean Partin, my Mamma Jean, though not by name. (Mamma Jean had, coincidentally, the same sounding name as one of John F. Kennedy’s mistresses, Marilyn Monroe, who was born Norma Jeanne Mortenson; Mamma Jean bore a striking resemblance to the famous model and actress, and had apparently wooed Big Daddy with her famous fried catfish method, if you can imagine what that would look like.)

“Pursuant to the general instructions he received from federal authorities to report “any attempts at witness intimidation or tampering with the jury,” “anything illegal,” or even “anything of interest,” Partin became the equivalent of a bugging device which moved with Hoffa wherever he went. Everything Partin saw or heard was reported to federal authorities, and much of it was ultimately the subject matter of his testimony in this case. For his services, he was well paid by the Government, both through devious and secret support payments to his wife and, it may be inferred, by executed promises not to pursue the indictments under which he was charged at the time he became an informer.

This type of informer and the uses to which he was put in this case evidence a serious potential for undermining the integrity of the truthfinding process in the federal courts. Given the incentives and background of Partin, no conviction should be allowed to stand when based heavily on his testimony. And that is exactly the quicksand upon which these convictions rest, because, without Partin, who was the principal government witness, there would probably have been no convictions here. Thus, although petitioners make their main arguments on constitutional grounds and raise serious Fourth and Sixth Amendment questions, it should not even be necessary for the Court to reach those questions. For the affront to the quality and fairness of federal law enforcement which this case presents is sufficient to require an exercise of our supervisory powers. As we said in ordering a new trial in Mesarosh v. United States, 352 U. S. 1, 352 U. S. 14 (1956), a federal case involving the testimony of an unsavory informer who, the Government admitted, had committed perjury in other cases:

This is a federal criminal case, and this Court has supervisory jurisdiction over the proceedings of the federal courts. If it has any duty to perform in this regard, it is to see that the waters of justice are not polluted. Pollution having taken place here, the condition should be remedied at the earliest opportunity.”

I’m not a lawyer, and I read on Wikipedia that the fourth amendment says, among other things, “warrants must be issued by a judge or magistrate, justified by probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and must particularly describe the place to be searched and the persons or things to be seized.” A walking bug sprung from a Baton Rouge jail cell could violate a lot of things.

As for the sixth amendment, I’ve never read it. For all I know, it could exclude brown people, Arabs, Cubans, or me from some inalienable rights.

I believe Chief Justice Earl Warren knew more about the sixth amendment than I do. He had overseen the case that led to Miranda Rights, and they enforces everyone’s right to a public defense attorney if they can’t afford one, and reminding them that they have the right to remain silent; the world would be more peaceful if we practiced that right. I don’t know if, as Warren said in Hoffa vs The United States, the waters of justice are still polluted; nor do I know what he would have said if he knew the ghosts of Big Daddy and Jimmy Hoffa would resurface and become a cornerstone upon which the foundation of the brilliantly named Patriot Act: “Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism.”

President George Bush Junior’s brainchild after 9/11, the 2001 Patriot Act justified monitoring cell phone messages of hundreds of millions of people without a warrant, using software to scrub messages looking for, per Hoffa vs The United States, allowances, “anything of interest.” Not only did a few words uttered by Hoffa land him in prison, a few words mentioned by Walter Sheridan when prepping Big Daddy crawled off a page in 2001 and touched millions of people’s private messages.

In one of the most hilarious coincidences I’ve ever learned, Bush’s leading legal advisor was a Harvard law professor named Jack; Jack Goldsmith was previously Jack O’Brien, the adopted son of Chucky O’Brien, Jimmy Hoffa’s adopted son. When Jack O’Brienwas in law school at Yale, he changed his name to his biologic father’s, because Chucky O’Brien was still under FBI investigation for Hoffa’s disappearance and other mafia-related shenanigans. (Almost all mafia film charatertures of a short, squat, bulldog, fiercely loyal to Hoffa or one of the families, are based on Chuckie, and a few months after I’d leave Cuba, he’d publish a book exonerating his stepdad, “In Hoffa’s Shadow,” and he had a few things to say about The Irishman film.) Jack disagreed with many points of the Patriot Act, but did his job under presidential orders, and presented legal justification rather than presenting a moral or ethical case. (I enjoyed reading his book.)

A lot of people hold grudges across generations. I grew up hearing history teachers refer to the civil war as “the war of northern aggression,” and for a period in my youth, what other people said first shaped my thoughts thereafter; downtown Baton Rouge buildings still have bullet holes from northern troops, and it wars can affect you differently when you see reminders daily, and for generations. Somehow, despite good people in this world, the Patriot Act led people to believe the president himself wanted them to torture of suspected terrorists in Cuba’s Guantanamo Bay, all held for more than fifteen years without an attorney, trial, or any inalienable right offered on American soil; and we forced that base onto Cuba. The Guatanamo prisoners were only three hours west of where I was checking voice mail and sending messages from my cell phone. I didn’t know how Cuba monitored air waves, or if local law enforcement harbored resentment about America forcing a base on their soil in Guantanamo Bay, or about what was going on there.

In addition to Guanatanamo, many Cubans were still resentful of President Kennedy’s botched Bay of Pigs invasion that killed some of their fathers, and distrustful of seemingly benign tourists after America killed Cuba’s adopted son, El Che Guevara, using CIA operatives in Bolivia. A few old Cubans may even remember their father’s talking about President Rosevelt’s Rough Riders killing their great-grandfathers, and many may have more stories, whether true or not, and you never know which local official harbors deep seeded resentment against gringos. The slang word, gringo, stems from Latin Americans wanting Americans in green uniforms to go away.

I glanced at my watch. I could still beat the happy hour crowd. Should I get another WiFi card and wait, just in case?

I sighed and put away my phone.

I was on sabbatical, I reminded myself, and could look forward to lots of diving and climbing over the next few months. I had a book to research and write. Havana was the perfect place to be still and write. Hemmingway had written The Old Man and The Sea in Havana, before Kennedy enacted the embargo against Castro, and he donated his house the the people of Cuba as a place of quiet contemplation that I planned to visit his home and be still for a while, to see if the ghost of Papa Hemmingway would poke his head up and be my muse. I had intel that Big Daddy had been in Havana after Kennedy’s embargo against Castro, when no one was supposed to visit, a year before Kennedy’s murder on 22 November 1963. Before flying to Cuba, I had downloaded the equivalent of a library’s worth of old court reports, news articles, and records onto my phone, along with a respectable playlist of music and eight downloaded albums, and I had spent all day on airplanes reading my family history and listening to a mix of New Orleans jazz and funk, ranging from Dr. John to Galactic and Trombone Shorty, and including a few bands Spotify recommended based on Cuba’s Cima Funk and The Buena Vista Social Club. I was going to finish a lot of lingering projects once freed from the tether of my cell phone, motivated by the ghost of Hemmingway, and lubricated by a few daiquiris.

I thought: I had a lot on my mind when I first listened to Wendy’s voice mail, and may have been distracted and therefore overreacted.

Obviously, Wendy had a lot to handle back then. Big Daddy had federal protection, FBI and marshalls following him for physical protection, and Bobby Kennedy, who was assassinated in 1968, had built a federal support group to keep Big Daddy out of jail as long as Hoffa was in prison; Bobby hated Hoffa enough to ensure he could reach up out of the grave and keep him locked up, because if Big Daddy were facing prison, he’d say anything to get out, including releasing Hoffa. President Nixon would pardon Hoffa, and everyone knows what happened to both of them in the 70’s. For jurors in the cheap seats: in 1972, Wendy was a single, teenage, uneducated mother married to Edward Grady Partin Junior, surrounded by federal marshals theoretically protecting us from mafia hits, while Hoffa languished in federal prison and could only be released if Edward Grady Partin Senior recanted his 1964 testimony. While in prison, Hoffa sent word to the families that Big Daddy should be kept alive (any FBI recordings would be to his advantage) and that he’d forgive all “family” debt owed by his “friends.” The national mafia families collectively owed Hoffa around $121 Million, though that part wasn’t mentioned out loud; it’s since been verified, but that doesn’t help Wendy and me. In the late 60’s and 70’s, $121 Million would be forgiven for “everyone” if “anyone” found “any way” to get Big Daddy to either recant his testimony, or testify against Bobby Kenedy’s team for using illegal wiretapping to plot their strategy. Fate, in a cruel twist, listed Wendy and my address in the Baton Rouge phone book under my father’s name, Edward G. Partin, and most low level hitmen could read. $121 Million was a lot of money back then.

Wendy and I rarely discussed the 1970’s and early 80’s, when I finally began living with her, but her therapists and psychiatrists said she had PTSD from the experiences. I didn’t want to nudge her for details beyond what she wanted to discuss. When she began talking about the time around when I was born and she abandoned me, she’d pause, change gears, and laugh, saying she was born WAR, but marrying a Partin WARP’ed her, and that’s why she drinks now. She never visited our history with me, and sometimes when she called it was the beginning of wanting to talk but always evolved into sadness. I had allowed myself to become conditioned, to expect the same pattern, and that’s what I began to see in her Havana voice mail. My initial sense of dread began to transition into irritation at repeated patterns: how did I go so wrong in raising my mother?

I thought: It had been a long day, and I may have overreacted to her voice mail.

I said to myself: She was probably just drunk and sad about one of her dogs.

I sighed and thought: What do I do next?

I sighed again. I wanted a drink. I was Wendy’s son, and old habits are hard to break. I straightened my back and neck, looked forward, breathed, smiled, breathed again, and limped across the plaza and to a bar. In the back of my mind, I hoped no one would notice anything remarkable about me, except, of course, the obvious XXL Force Fins strapped to my backpack; I’d ditch them at the casa and switch to a discrete daypack for the next few days.

I had the feeling it would be a remarkable trip, regardless if I reached Wendy before going offline. In the worse case, I had read in The Lonely Planet that the diving and climbing in Cuba alone was worth the trip, even if you didn’t solve Kennedy’s murder or bring McDonalds breakfast sandwiches to prisoners locked up in Guantanamo. No matter what happened, I was luckier than a most people on Earth that day. That’s Freedom. According to a professor I know at the University of San Diego’s Shiley-Marcos School of Engineering, that feeling of gratitude leads to success in socially responsible entrepreneurship, whatever that means. An abundance of freedom means you have enough to share.

Wendy would pass away six weeks later of liver failure secondary to alcohol abuse. She had been on the liver transplant waiting list for three years; I never suspected, but more of our conversations and her jokes make more sense in 2020 hindsight. Wendy Anne Rothdram Partin would have turned 64 on August 14th, 2019. The doctor marked her death at 9:36am. I would have given her longer, if I could.

Go to Table of Contents