New Orleans

“[Jimmy Hoffa’s] mention of legal problems in New Orleans translated into his insistence that Carlos Marcello arrange another meeting with Partin, despite my warning that dealing with Partin was fruitless and dangerous.”

Frank Ragano, J.D., attorney for Jimmy Hoffa, New Orleans mob boss Carlos Marcello, and Cuban exile and Miami mob boss Santos Trafacante Jr., in “Mob Lawyer,” 1994

I straddled my backpack on both shoulders and limped across the Plaza San Francisco de Asis towards a small bar and grill. It had double doors wide open so that live music flowed out of the bar and across the plaza, and the open doors attracted my attention more than the other venues circling the square plaza. I needed to move my body and stand up for a while to settle my mind. I’m slightly claustrophobic – for lack of a better word – and after a long flight I always felt cooped up and about to burst from pent up energy. The double wide doors seemed like an acceptable compromise between being outdoors and wanting food and a drink, and it had a standup bar.

Sitting is one of the worst thing anyone can do for their body. At least five randomized, double blinded clinical trials with and a meta analysis of more than 850,000 people followed over fifteen years by independent research teams says so. I walked into a bar so that I wouldn’t become a statistic. As for why sitting is risky: a right angle bend increases lumbar disc pressure 120% due to muscles yanking on your spinous process to maintain static equilibrium, so every minute sitting is, to your spinal discs, an unrelenting pressure that squeezes out lubrication, cushioning, and nutrients. In normal activity, walking and moving, your discs pump and nutrients and toxins exchange via mechanical osmosis. Your disc isn’t innervated in the nucleus, so we don’t feel the pressure until our annulus is desiccated years later, and the outer innervated layer is relatively dry and itchy and painful. It’s too late to do anything by then, because the disc isn’t vascularized. Any healing potential is negligible; from nature’s standpoint, you’re beyond child rearing years and redundant, not worth the time and energy to heal.

Sitting also puts pressure against the back of your thighs and restricts blood flow, so toxins accumulate in your legs and you have less oxygen reaching your brain and your mental processing becomes sluggish. Most people don’t notice, and believe sitting is relaxing. People who sit for a living, like truck drivers and office workers, have the highest rates of low back pain and diabetes; with sluggish blood flow, your body doesn’t use sugars as nature intended, and diabetes develops. Nurse aides have back pain, too; not because they sit, but because they reach over to move patients and send spikes of forces many times normal load through uninervated nucleuses, and the long term consequence is similar to sitting, though without disproportionately high rates of diabetes, like truckers and sedentary office workers.

The Buddha famously advised acting moderately, and he added, unambiguosly, to keep your mind alert you should not sit on chairs or high above the ground, but to sit cross legged when you want to watch your mind and lose unwholesome habits. In other words, he noticed his mind’s sluggishness when sitting too long, and his thoughts suffered. (I read he was the first to teach vispassana, observing your mind and seeing that your thoughts are like breathing, partially in control and partially automatic; a clear mind can discern the two, and detach yourself from unwholesome thoughts.) Winston Churchill noticed the same thing, and he used a standing desk to plot England’s WWII strategy. Thomas Jefferson saw it, too, when planning the U.S. constitution, and he designed and patented his own desk. (Jefferson’s standing desk on display at his Monticello home, and he’s a reason the American constitution strongly advocates patent rights to kindle and reward innovation.) Earnest Hemmingway used a stand up desk later in life, including the years he lived in Havana; he put a shotgun in his mouth when he retired to Idaho, so any advice or research result should be taken as a food for thought and not applied as doctrine. The Buddha himself said to not trust anything he said blindly, but to learn from experience.

I chose to stand whenever I can, from my personal experience in a brief stent as an office engineer in 1999, and by remembering Big Daddy and learning from his experiences.

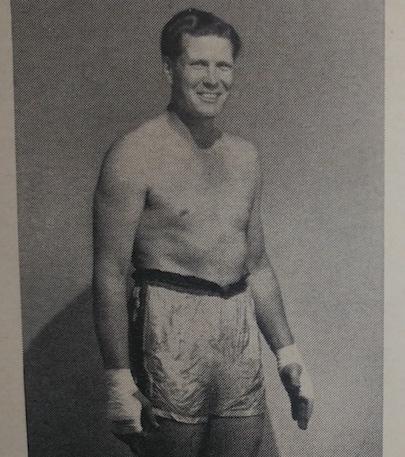

Big Daddy was released from prison five years early for declining health due to diabetes and an undisclosed heart condition. He had never sat around all day until he went to federal prison in 1980, and when I saw him in 1986 he was a deflated ballon of his former glory. I was young and influential, and his change stuck in my mind. He had been active when I first knew him, never sitting like the thousands of Teamster drivers he oversaw and represented, ironically fighting to increase their short-term paychecks and provide them long-term health benefits from companies and the Teamster pension fund (a Ponzi scheme that depended on increasing the number of young Teamsters paying monthly dues to honor older pensions, and an increase in union contracts with Louisiana companies and Hollywood movies filmed in Louisiana). He was always busy, helping his mother, Grandma Foster, around the house, fishing in False River, hunting elk in near Boulder and Flagstaff, boxing, beating people, tossing safes and bodies into rivers, and fending off small teams of low-level mob hitmen foolish enough to try their luck with nothing but a few knives and measly .38 specials. Sitting killed him when ten years of mafia hits could not. He died on March 11th, 1990, at age 66.

Like a lot of kids, I never forgot the lessons my grandfather taught me, nor will I forget his final words: “No one will ever know my part in history.” It sounds funny, if you say it out loud and enunciate Ed Partin: no one will ever know my part in history; I hope that helps you see where I get my interest in Hoffa’s disappearance and the Kennedy assassination, and why I try not to sit still too long.

And, now you can laugh at my favorite pun with Wendy: Ed Partin was a big man with a part in history, and I’m just a small part in his story. She had her WARP’ed joke about Ed Partin, I had my small part in his story.

I took a deep breath, exhaled slowly, straightened my posture, and strolled inside the bar. Happy hour was just beginning, and small bands were beginning to play to entice people inside after work. I walked past the band and stood at the bar a few feet from the young trumpet player farthest from the doors, and rested a foot on the brass rail below the bar. A long time ago, people designing bars and wild-west saloons didn’t have 850,000 person meta analysis’s, but they realized that a foot rail reduces spinal loads, and the muscles from balancing pump blood up from your feet to get oxygen and keep your mind alert, especially if you alternate feet every now and then. I have big feet, so there’s a lot of blood down there that pools and makes my brain stagnant if I didn’t move around a bit now and then. I’m no buddha, but, even before I had so much scar tissue, I noticed the benefits of standing more often when I began studying engineering at LSU. Those were the good old days, when I still had cartilage, enjoyed flying, and rarely landed with the plane.

I glanced around the bar. Only about half the people were focused on the band, but even those chatting or laughing moved their bodies to the beat, channeling the band’s vibes or vice versa. Good music is a collaborative experience, and the vibe was right. It was the perfect time for me to start happy hour, before the crowds arrived after work, and I could read at the bar. I should have been happy, in my version of a slice of heaven, but I caught myself sighing again. My mind had drifted back to Wendy and my aching back, and my posture had slouched. I realized I wasn’t helping the room’s energy. Drastic measures would be necessary.

I straightened myself again and kept an eye up for the young light skinned bartender to notice. He saw me and began walking over. He had a wide smile and was wearing a casual Cuban styled button up short sleeve shirt, and sported a haircut that required a bit of extra effort every day before work and probably spoke softly to his female clientele. He was calm and confident, and leaned forward and said something I didn’t understand because of the band, but I assumed and shouted that I’d like a Hemingway daquiri and whatever seafood tapas were on special. I rotated my head to listen to what he said, but I couldn’t make out the words. I smiled enthusiastically at whatever he said, and gave a “thumbs up.” He smiled back, patted the counter to say he understood, and went to work.

He brought out the daquiri a few minutes later, but the food from the kitchen took about a song and a half longer. I sipped the drink on an empty stomach while I waited, and the placebo effect loosed my mind before the alcohol seeped into my brain. I finally began to unwind when it hit. I sighed a good type of sigh, not intentional, like when I decided to walk in, but the type of sigh that begins as a feeling of contentment and builds inside you and spills out through your lips as a sigh. The music sounded brighter, my thoughts had subsided, and my body joined the party. I was finally contributing to the room’s energy, in my own way.

I moved to the beat while inspecting what the bartender had delivered. The daily special was “calamar a la parilla,” grilled squid, cooked longer than ideal and toughened. I wasn’t complaining, I just liked nuances of seafood and was trying to enjoy myself, and I build up ideals that can rarely be met. It was fine calamar a la parilla for anyone who didn’t know otherwise. My eyes lit up, though, when I dipped a slice of squid in the side of mojo sauce, the first time I had ever had it. It was packed with roasted garlic and a tang from what was probably freshly squeezed orange juice, with just enough chili pepper heat to, as Chef Paul Prudhome of Commander’s Palace fame said, “wake up the taste buds and let them sense everything.”

I sliced the next bite of squid thinly and spread the creamy mojo on thickly to add some squish and compensate for tough calamar. I savored the next bite; the creamy mojo balanced the chewy better than I could have planned; sometimes, rolling the dice pays off more than choosing one way or another. I sighed again, a pleasant, content, relaxing sigh that rippled through my body and spoke more eloquently than the worry and discomfort, and all I could hear for a blissful moment was that mojo sauce and the rhythm of a six man band.

The Hemingway daquiri was strong and good and I ordered another. I sipped it gently to lower the liquid in the steeply angled margarita glass, one like Uncle Bob’s martini glasses that Auntie Lo would spill when she got sloshed; they were Wendy’s aunt and uncle first, and we’re creatures of habit. I never saw Uncle Bob spill a drop, and he’d quote some Asian philosophy from the Tao Te Ching that nothing can be added to a full cup, and it soon spills. I sipped a bit more so I wouldn’t spill as I ostensibly danced to the band’s groove; I was actually stretching. Stretching became grooving after a few more sips, though I didn’t notice the transition. Cuban Funk seems to be made to move Even the private driver I had hired to take me from the airport had tapped his fingers on his steering wheel as we cruised into town with Buena Vista Social Club blaring on his upgraded Bluetooth stereo. All around town, it seemed, people tapped their fingers to the beat of whatever music was nearby, and people in the bar did the same while chatting with each other or focusing on the band and moving whatever part of their body wasn’t stuck to their chair. I couldn’t imagine a better first day of vacation.

I had heard of the Buena Vista Social Club in America, if only because of the film, but there was more music worth discovering. I was anxious to listen to bands I hadn’t heard yet. I had a few ideas to prime the pump, because I’ve seen Cuba’s Cima Funk play with New Orleans’s Dumpstaphunk – with a ph – at Tipatinas, an old fruit stand turned hip music venue near the river’s Irish Chanel. Cima Funk opened with a few local musicians for Trombone Shorty, two of the Neville brothers, and a few members of Galactic, who had just purchased Tipatinas and was having a party to celebrate. Everyone there was enthusiastic about the Afro-Cuban music scene, which is like the Pope saying he digs another preacher’s sermon. A seed was planted in my mind at a late night show after a couple of local beers, and a week later I saw a few other Cuban and Carribbean bands two hours away, at Lafayette’s Festival International, and the seed sprouted. I saw a news blurb about the Obama entrepreneurship loophole, and the sprout skyrocketed. I requested a visa and was approved, and a year later the tree bore fruit and I was standing in Havana savoring a Hemmingway dacquiri, as if it were meant to be. Cristi called it synchronicity.

Despite the bar’s vibe and my groove, I didn’t stop thinking about Wendy. My initial reaction had left fight or flight hormones lingering longer than I could force away. I tried to focus on the music, but I kept going back to my initial sense of dread, doubting my decision and wondering if there was something to her message.

Maybe I had just been grumpy after a long series of flights, I thought to myself. I had been squished between different groups of big, chatty people on each leg, and I almost leaped from the plane before we rolled to a stop. As soon as we could take off seatbelts, I stood up and held my carry-on backpack and walked briskly from the plane to a row of private cars and asked for the closest place to buy a WiFi card ang get public access. It seemed like so long ago that I was surprised by the lingering feelings and the ruminating thoughts about Wendy and her history.

The band took a break, probably refreshing their energy before people began filtering in after work. I took advantage of the quiet to focus my thoughts, and I opened my phone and the synced Dropbox folder titled JipBook – I’m Jason Ian Partin – and read Chief Justice Earl Warren’s missive about Big Daddy. He was the only dissenting judge against allowing Big Daddy’s testimony to send Hoffa to prison. He wrote:

“Here, Edward Partin, a jailbird languishing in a Louisiana jail under indictments for such state and federal crimes as embezzlement, kidnapping, and manslaughter (and soon to be charged with perjury and assault), contacted federal authorities and told them he was willing to become, and would be useful as, an informer against Hoffa, who was then about to be tried in the Test Fleet case. A motive for his doing this is immediately apparent — namely, his strong desire to work his way out of jail and out of his various legal entanglements with the State and Federal Governments. And it is interesting to note that, if this was his motive, he has been uniquely successful in satisfying it. In the four years since he first volunteered to be an informer against Hoffa he has not been prosecuted on any of the serious federal charges for which he was at that time jailed, and the state charges have apparently vanished into thin air. Shortly after Partin made contact with the federal authorities and told them of his position in the Baton Rouge Local of the Teamsters Union and of his acquaintance with Hoffa, his bail was suddenly reduced from $50,000 to $5,000 and he was released from jail. He immediately telephoned Hoffa, who was then in New Jersey, and, by collaborating with a state law enforcement official, surreptitiously made a tape recording of the conversation. A copy of the recording was furnished to federal authorities. Again on a pretext of wanting to talk with Hoffa regarding Partin’s legal difficulties, Partin telephoned Hoffa a few weeks later and succeeded in making a date to meet in Nashville, where Hoffa and his attorneys were then preparing for the Test Fleet trial. Unknown to Hoffa, this call was also recorded, and again federal authorities were informed as to the details.“

Warren’s missive was lengthy, even for a missive. He obviously had a big bug up his ass and wanted to let it out. After a few more paragraphs of ranting about Big Daddy, Warren mentioned my grandmother, Mamma Jean, though not by name.

“Pursuant to the general instructions he received from federal authorities to report “any attempts at witness intimidation or tampering with the jury,” “anything illegal,” or even “anything of interest,” Partin became the equivalent of a bugging device which moved with Hoffa wherever he went. Everything Partin saw or heard was reported to federal authorities, and much of it was ultimately the subject matter of his testimony in this case. For his services, he was well paid by the Government, both through devious and secret support payments to his wife and, it may be inferred, by executed promises not to pursue the indictments under which he was charged at the time he became an informer.

This type of informer and the uses to which he was put in this case evidence a serious potential for undermining the integrity of the truthfinding process in the federal courts. Given the incentives and background of Partin, no conviction should be allowed to stand when based heavily on his testimony. And that is exactly the quicksand upon which these convictions rest, because, without Partin, who was the principal government witness, there would probably have been no convictions here. Thus, although petitioners make their main arguments on constitutional grounds and raise serious Fourth and Sixth Amendment questions, it should not even be necessary for the Court to reach those questions. For the affront to the quality and fairness of federal law enforcement which this case presents is sufficient to require an exercise of our supervisory powers. As we said in ordering a new trial in Mesarosh v. United States, 352 U. S. 1, 352 U. S. 14 (1956), a federal case involving the testimony of an unsavory informer who, the Government admitted, had committed perjury in other cases:

This is a federal criminal case, and this Court has supervisory jurisdiction over the proceedings of the federal courts. If it has any duty to perform in this regard, it is to see that the waters of justice are not polluted. Pollution having taken place here, the condition should be remedied at the earliest opportunity.”

I didn’t know if the waters of justice are still polluted, nor did I know what Warren would have sadi about The Patriot Act, especially because he contradictorily championed the1940’s unjust imprisonment and detention of 250,000 Japanese and Japanese-Americans in west coast camps shockingly similar to Hitler’s concentration camps. It was the 60’s, and I hoped America was different back then. I doubted I’d ask anyone in Guantanamo what they thought about it.

I sighed, and shook my head to swirl the daquiris around and refocus. I had reread Warren’s reports so many times that I doubted I’d notice anything new. But, I’ve learned that I see things differently with age, and every now and then a single word triggers a thought and leads me down a new path. Uncle Bob had been right: you can’t pour more martini into a full cup, and you can’t be open minded to only some things. It’s tedious to reread sixty year old reports with an open mind, especially exhausted from flying, and I couldn’t focus. I was still on west coast time, and felt I should leave soon, mostly because I had had two daiquiris and wanted to avoid the temptation of standing next to a bar.

I put my phone in the padded pocket on my backpack by the foot rail and waited for eye contact with the bartender. He had been busy running plates of food from the kitchen cutout to tables around the room. When he saw me, I smiled and held up Uncle Bob’s old gold money clip with a discrete credit card and neatly folded greenbacks; it was so old school that it spoke eloquently without me needing words.

“La cuenta, por favor,” I said when he approached, just to practice articulating Spanish words. He patted the counter, swung around, and returned a moment later with a bill and slid it across the bar to beside my empty glass. We chatted with the now quiet room, and he asked how I spoke Spanish so well. I chuckled to imply I was flattered or that it wasn’t a big deal, and said I lived in San Diego, on the border of Tijuana, and I couldn’t help but learn Spanish, “como la o’smosis.” He chuckled back at that, which told me I probably pronounced it correctly. I have a hard time with most accents and never quite lost my southern murmur, or Wendy’s quick grouping of words when buzzed, so I practice saying new words to help me focus.

The band began plaing again and I paid in U.S. Dollars and said, with eye contact and a nod of my head that could be heard over the band, “No necicitto cambio.” The bartender picked up the cash and smiled genuinely and waved as he said “Gracias! Buen viaje!” I put on my backpack and turned towards the door and began walking out. I dropped $5 bill folded in half into the band’s tip jar shaped like a spittoon, smiled, and clasped my hands and bowed a thank you to them without interrupting. At least, I hope it was a tip jar and not the band’s spittoon. I think it was a tip jar, because the trumpet who had played next to me locked eyes and nodded with his horn without missing a note.

I walked out the double doors, paused, and breathed in deeply. I caught a whiff of sea breeze, then sighed and smiled. I limped to my downtown casa particular, trying not to let my gimpy gait be noticeable, and realizing how tired I must be to not even walk straight. Anyone watching probably assumed it was the daiquiris, and they might have been right.

Go to Table of Contents