Wrestling Hillary Clinton: Part VI

“Following the completion of its investigation of organized crime, the committee concluded in its report that Carlos Marcello, Santos Trafficante, and James R. Hoffa each had the motive, means, and opportunity to plan and execute a conspiracy to assassinate President Kennedy.

Congressional committee on assassinations report on the murders of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Junior, 1977 (classified until President Bill Clinton released part of the file in 1993)

The day after I was emancipated, Lea picked me up at the Abrams’s house at 10:30am for an 11am appointment at the department of motor vehicles. I was done by 12:30pm, and she dropped me off at Belaire and then went to Hammond, where she was registering for classes and meeting with three girls who had advertised in the paper that they would like a forth roommate to split costs in an house near campus.

I had my bootleg copy of Vision Quest in my backpack; my plan was to leave it at school and motivate the team to watch it after school and begin practice a few weeks earlier.

And I needed to register for classes, too; or, more specifically, sign my schedule from the end of last year, because I never got around to having Wendy sign it.

I planned to do both and then jog home to the Abrams’s house, which was only three and a half miles away; but the wrestling gym beckoned me.

I tightened my backpack straps and strolled past the front office without blinking. Less than a minute later I stepped through the gym doors and instantly felt at home.

There were no bleachers. This practice room was for practice only, and it barely held a basketball court in the center, three segments of wrestling mat rolled and pushed to the side wall, and a caged weight room for the football team. I took a deep breath, and inhaled the smell of fungicide mixed with what I think was burnt rubber from basketball skid marks on the wooden floor.

This is my home, I said to myself.

I emancipated so I could marry the love of my life without needing anyone’s signature ever again. This was what freedom felt like; real freedom, not the freedom like I had said every few days being emancipated. This is I wanted all along, I said in my head, but more like a realization than an affirmation, as if the thought popped there on its own.

A sharp noise from a clanging chain shot out form my left and echoed around the gym; it was Coach, clamping a padlock on the floor-to-ceiling chain link fence football weight room so that no one could go in unsupervised. He slid out the key and it rattled against a thick ring of keys that fit every room in Belaire, the school van, and a handful of outdoor sheds Belaire used for special-education and driver’s ed classes, and of course the weight room.

I turned and faced him and said: “Hey, Coach.” I said softly enough to not echo; it’s a skill, like any other, and I had learned it from him. In a loud and chaotic tournament with everyone’s voice bouncing off the walls, speaking softly is the most effective way to be heard. No matter how noisy the tournament, I was able to hear him when I was on the mat every time he spoke.

He smiled a bit more broadly and walked closer and said, “Hello, Magik.”

He kept walking without pausing and clasped my right tricep on his way through the door; I had no choice but to follow.

“Coach?” I said as we walked.

I don’t know why I hesitated. I took a breath and stood up straight and strolled at my own pace; with conviction, I said: “I’d like to show the team and new wrestlers Vision Quest before season begins. Could I borrow the VCR?”

He paused and looked up at me.

There was no chance of him saying “I don’t know? Can you?” like the sarcastic geometry teacher said, just so they could say, “But you may borrow the VCR.”

That was a beauty of Coach. When he said, “Good job, Magik,’ he meant it, each and every one of those 105 times; he trusted me to be doing the best I could, and nothing he could say would help me at that moment.

“Well,” he said. “When did you want to use it?”

I repeated that I’d like it before season, but realized it was ambiguous. Then the words “late October to early November, like maybe just after Halloween,”

“But if we can get waivers signed by freshmen parents sooner,” I said, feeling slightly surprised that I what I was about to say was right: “We could start practice right after Homecoming.”

Coach chewed on that for a minute; Belaire held its Homecoming Dance in that gym.

“I don’t see why not,” he said. “But I’d like to watch it first. What’s it called again?”

“Vision Quest,” I said.

“I don’t see why not,” he repeated. “But I’d like to take a look at it first. You have a copy?”

Though Coach was in the USA Wrestling hall of fame, he didn’t know much about Vision Quest, other than it stared Madona.

The 1983 film was based on a book by the same name that John Irving, the famous author who was also in the wrestling hall of fame, had said that Vision Quest was the best book about wrestling he had ever read. To put that in perspective, Irving had wrestled in high school and college, and was the an English teacher who was the assistant wrestling coach at his town’s high school team; he had told reporters that after college, he realized he could either wrestle well or coach well or write well, but could not do all; he chose to write, but he writes about people who wrestled in high school, and he’s an assistant coach.

Irving’s also in the USA Wrestling hall of fame, but he writes about that in his nonfiction, where he admits he was no where good enough to wrestle like the greats. I once overheard – and I believe this to be true – when he was at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop training under the legendary Kurt Vonegut, John Irving mentioned that the greats of wrestling were Iowa’s Dan Gable, Indiana’s Doug Blubauh, and Iowa State’s assistant coach, Dale Ketelsen, which is where Coach was when LSU recruited him from there in 1968 and Irving was at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop.

Irving would tell anyone who asked the distinction, that he was in a category of the Hall of Fame for people who wrestled good – maybe saying just their best – and were famous; their fame got them into the Hall of Fame, not their wrestling skills. It was to show kids that the skills of wrestling carry over into life. Alumni include a roster of celebrities, former professional football and basketball players who had also wrestled and said that wrestling taught them skills they used in other sports, anVice-President Dick Cheney, who would go on to shoot his friend in the face with a shotgun (because no one is perfect). Irving’s point was that he was not one of the greats, nor was Dick Cheney or other celebrities who were in that Hall of Fame, but that Coach Dale Ketelsen was one of the greatest wrestlers who ever lived.

He just hadn’t watched Vision Quest yet.

I said, “Yes, Coach. I have a copy.”

He nodded and clasped my tricep in his vice-grip, and we walked into the coaches’s shared offices and he showed me how to unlock the closet and pull out the bulbous television on a metal stand; the stand’s middle shelf had a bulky rectangular VCR, and the lower shelf was a 50-foot coil of orange extension chord. The football team used it to watch replays of their game while sitting in the bleachers, and sometimes classes of kids came in to the main gym to sit in bleachers and watch state-mandated safety and stay-off-drugs videos.

“Here,” he said, handing me his ring of keys. “I have to go to a meeting, but if you set it up I’ll be back by 2:30 and we can watch it then.”

I took the keys and he clasped my right tricep again. He held up his right forefinger like he did whenever he said something he would only say once.

“Listen,” he said. “If you’re going to be co-captain, I’d like you to make at least a B average this year.”

Armed with Coach’s hefty key rink, I scuttled back to the front office and opened the door.

“Hello, Magik,” said the principal and vice-principal’s assistant; she knew me well from when I used to be there once every few weeks for disciplinary problems in the 10th grade, and she’s the one who had reminded me a few weeks before that I wasn’t registered for classes. I can’t recall her name, but I said hello back and asked to see Mr. Vaughn. Coincidentally, he opened his office door and stepped out.

“Well hello, Mr. Magik,” he said. “Coach Ketelsen put you to work today?”

I shook my head no, and said I had to register for classes and that the lady whose name I can’t recall said he had to waiver my registration because it was late. He said sure, and the assistant pulled my record and the form that had been filled out last semester but not signed by me or my parents.

“Coach wants me to earn a B average,” I said without knowing why.

“I can see that,” Mr. Vaughn said. “You’re capable, Magik. You just need to focus.”

On impulse, I told Mr. Vaughn I had been emancipated and joined the army; I whipped out my paperwork to prove it. He looked at my contract and handed it back. He didn’t comment on how I did it, so I told him I was emancipated; I don’t know if that registered, because I quickly said that I’d like to sign up for physics.

“And calculus,” I said. I didn’t know what that meant, but I knew it was hard, only for the top students, and Ben would be in that class; Mrs. Abrams was a math teacher, and Ben was a straight-A student, and I think I felt that if he could do it, so could I; after all, I had seen him wrestle.

“Physics and calculus,” Mr. Vaughn repeated. He asked his assistant for my folder.

“You haven’t passed geometry,” he said. He looked at my record a second longer and added, “Or chemistry.”

He looked down at me from his 6-foot lean frame and said, “Why do you want to do this?”

I rattled off something about joining the 82nd and wanting to do my best in everything and wanting to be challenged and knowing I could do it. When I finished, I realized I also wanted something Lea and I could do together when she visited me during her first semester at Southeastern.

He stood tall and quiet for about twenty seconds, then said yes. He signed the waiver, and reminded me that the state requires three maths and three sciences to graduate, so to leave for the army I’d need to also pass geometry and chemistry. To make room for two classes atop my repeat math and science, I had to give up workshop and public speaking, two classes often used to bolster an athlete’s grade point average so they met state requirements, and probably a reason that to this day I’m practically useless with a Skill Saw.

Unlike Coach, Mr. Vaughn would follow through with me the rest of the year. There’s no one way to lead, and given that I’d become valedictorian of graduate school in engineering and lead college courses in physics, whatever Mr. Vaughn did must have worked. But I don’t know why he took that risk; had I failed, he would have taken heat for signing the waiver.

Finished with registration, I jogged over to Little Saigon with Coach’s keys held in my hand. Like how I impulsively spoke with Mr. Vaughn, I don’t know what I was doing anything that day.

I walked up to the same convenience store that sold bootleg cassettes and VCR tapes and cigarettes to kids. It shared a wall with a video arcade that was filled with smoking Vietnam veterans and kids who would be at Belaire later that year. I knew a few who were smoking outside, but I told them I was in a hurry and went inside the convenience store; I remembered that they had a machine that copied keys, but I don’t remember knowing that before I jogged over.

I asked for a copy of Belaire’s key to the smaller gymnasium, and held it up for them to see. They said sure, despite the blantant engraving that said, “Do Not Copy,” and I removed it from Coach’s keyring and rummaged through my backpack for my wallet.

I had $2 in half dollars and around a five or six quarters for the arcade in the zippered coin slot, and in the slot for bills I had a $1 bill, a $5 bill modified with a corner of a $1 glued with rubber-cement so it would remain flexible (it was for Mike Bornstein’s 1-and-5 switch in a spectator’s hand: you borrowed a 1 and your thumb hid the glued corner on your 5 as you folded it; the 1 in my wallet was in case they didn’t have one or their’s was too wrinkled to look like the glued corner), and an ordinary $5. I can’t recall how much the key was, but it was around $2 and I’d have to either break my $5 bill or use my extra dollar and some quarters.

I glanced around while they ground the key. The shop was owned by Vietnamese immigrants yet catered to Belaire as well as the community we called Little Saigon. When Saigon fell in 1975, hordes of Vietnamese who had helped Americans fled. Many settled in Baton Rouge. We shared a similar hot and muggy climate and an economy based on seafood and agriculture, and both southern Vietnam and southern Louisiana were once French colonies. A Bon Mi sandwhich really is a Vietnamese po’boy; a Vietnamese iced coffee is a New Orleans cafe’ au lait made with condensed milk, like they had in the MeKong Delta in lieu of cows and refrigeration; French baquettes were the same; and Vietnamese goose pate’ rivals what you’d find in Paris.

Like Americans, the refugees were capitalists; they catered to Belaire subdivision and adapted to our needs without regard to race, religion, or beliefs; all that mattered to them was that we spent money in their shops and they adapted to their customers’s needs.

Because Vietnam officially ended in 1975, fourteen years later a lot of Belaire kids had parents who were veterans; and because Belaire had a lot of cheap, one-bedroom apartments and a splattering of ramshackle homes, there were a lot of single veterans living off of disability nearby, chain smoking in the Vietnamese-operated video arcade and shopping in the Vietnamese-operated shops that sold rolling papers and things labeled glass lamps that we all knew were bongs.

I had watched Belaire kids had been playing video games and buying booze and cigarettes in Little Saigon since I was in elementary school and lived across with Wendy, and I had been shopping there since middle school, but I had never noticed the t-shirts before.

The walls of the convenience store were lined with hard-core grey military t-shirts with all black writing that I had seen plenty of times but never thought about. Never. Not once. I ignored them the way I ignored teachers in classes where I didn’t see how the subject applied to me. Now I was seeing things through a legal adult’s eyes, one who had set his sites on the 82nd Airborne.

One shirt had Airborne wings and lightning bolts and said: “Death from Above”

One with a skull wearing a black beret said: “Airborne Ranger” That was back when only Rangers wore a black beret, before it was given to everyone in the army to wear. Another skull with a black beret said: “Rangers never die, they just go to hell and regroup.”

One shirt showed criss-crossed M-16 machine guns, laid out like the Saint Andrews cross on rebel flags, and it said: “Kill ’em all, let God sort ’em out”

One had a nuclear bomb’s mushroom cloud and said: “Made in America by ‘lazy Americans’ / tested in Japan”

And more. They were everywhere, but I had never noticed them before.

I saw irony. Two years before, on Halloween and in an event that made national news, a kid from Belaire Middle School who was born in America to refugees from Saigon went trick-or-treating with his friends who had decided to dress as Saturday morning’s G.I. Joe characters. The Vietnamese looking kid wore a helmet and camouflage hunting outfit and carried a toy gun. When he took his turn knocking on a door in Belaire to say trick or treat, he was met by a Vietnam veteran with PTSD who instantly shot and killed the kid.

Like with the t-shirts and uninteresting classes, I hadn’t given that kid’s death a second thought, other than when I heard Wendy and her boyfriend talk about that’s why they needed to move away from Belaire and build a dream home away from Belaire and downtown. For the first time, I was seeing that they were mistaken, that it wasn’t them that was inspiring violence, it was us.

I didn’t know what to think. I walked around in a daze, confused at why I couldn’t stop staring at the army t-shirts and hats I had never noticed when shopping for bootleg cassettes and VCR tapes.

Then I saw a pile of jacket patches that caught my attention.

About half of the patches matched the t-shirts, and I can still see them in my mind’s eye: the First Armored Division’s tank and lightning bolt, the 10th Mountain’s crossed swords, the 101st Airborne’s Screaming Eagle, the Big Red One, and of course the 82nd’s AA’s, for All Americans, and the Airborne tab above them. Mixed in were patches from the hard-rock bands Pink Floyd, Black Sabbath, Leonard Skynard, Led Zepplin, and more of my dad’s era of bands; a few were Motley Crue, Twisted Sister, Ratt, and Def Leopard. But, what had caught my attention and jumped out at me, was a double-fist sized black and white skull wearing a magician’s top hat. It was Slash’s meme from the Guns-N-Roses band.

It was meant to be.

I did the math and realized I’d have to spend my Mike Bornstein $5. Without hesitation, I peeled off the $1 corner (another reason you use rubber cement is that it can be readjusted and reused). With cash in one hand and that patch in the other, I waited for my key.

I met Coach at 2:30 and had my bootleg copy of Vision Quest ready to go.

I waited by Coach’s desk. It was a cluttered mess of folders, paperwork, old black and white photos, wrestling magazines, and training manuals; but, in the opposite way from how I never thought about the army t-shirts in Little Saigon, I knew every piece of Coach’s clutter.

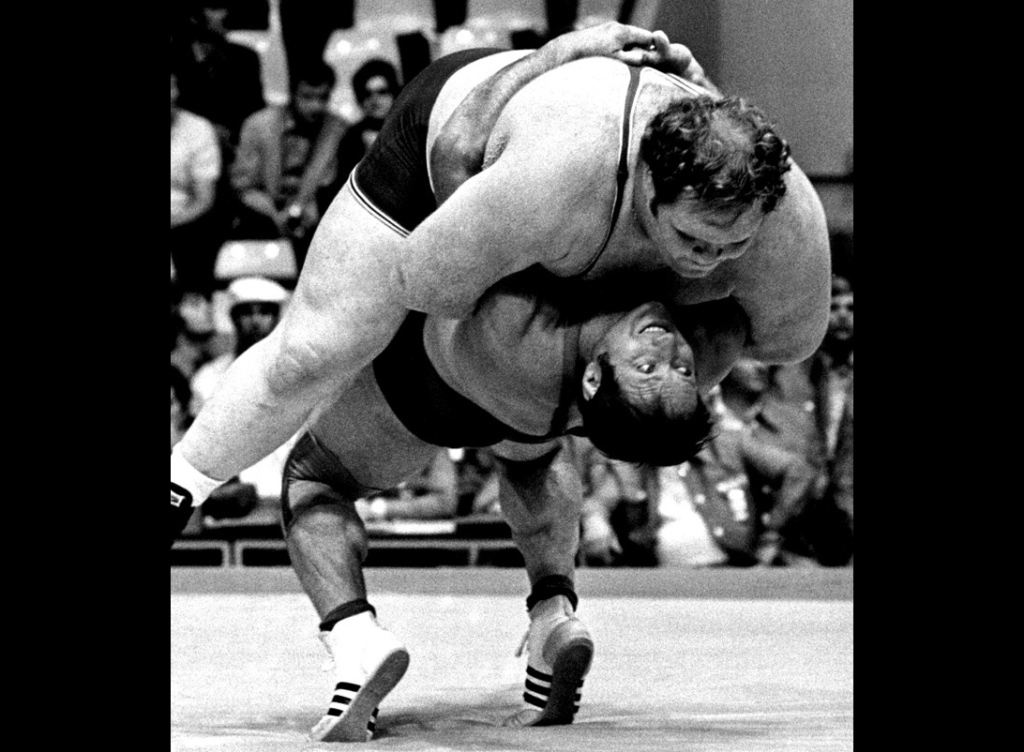

I picked up one photo from the 1972 Munich olympics, the year I was born, a famous one you can easily find online now and stuck in my mind then mostly because it was from 1972. It shows what was then the world’s heaviest heavyweight and largest Olympian to ever wrestle, a 22 year old American Titan who weighed something like 444 pounds, being heaved in a perfect arched bear-hug throw by West Germany’s aging heavyweight, a 38 year old still competing, but who wasn’t much bigger than Big Ben and was dwarfed by the American. They were in what was called the ultra-heavyweight, so one of their arms weighed more than Coach, but he knew the German, who had won a gold in the 1960 Rome Olympics when Coach was there. The American had defeated the German in Freestyle earlier that week, but in Greco-Roman, the tiring and aging German did in the second round what is sometimes called the greatest throw in wrestling, and he pinned the Titan and won an unexpected victory.

The 1972 Olympics news was dominated by the Munich Massacre, armed terrorists who kidnapped then killed Israeli athletes and coaches and a German, but Coach never talked politics. He talked about the wrestlers he knew and the lessons he learned. He kept in touch with practically every wrestler he met, no matter where they were from, and, like USA Wrestling said, he had forgotten more about the sport than we’ll ever know.

The Titan said he never thought he’d be defeated, especially by someone so small. Coach quoted him and had told the team that you never know what will happen, so just wrestle. He also said that that match was why USA wrestling and the Olympic committee changed rules to maximize heavyweights at 275; if you watch the video and notice the German’s neck crumpling under the Titan, you’ll instantly understand why.

Coach had a story for every rule. The half nelson is not as powerful as the full-nelson, but after a high school’s kid’s neck was broken by the full nelson, Coach, who served on national committees, said they had to make the sport safer. But, he added, safety rules are what allow you to give everything you have when you’re on the mat. Just get out there and wrestle.

I heard Coach coming and I replaced the photo and double checked that the TV was warmed up and the VCR tape queued up. He walked in and I handed him his ring of keys and he put them in his front pocket and they bulged the size of an apple. He tossed his clipboard full of paperwork on his desk, and smiled at me.

Coach was a man of few words. He pulled up one of the other coach’s chairs for me, and we sat down to watch Vision Quest together in silence.

About ten minutes in, Coach asked, “Is this what it’s all like?”

I said yes.

“But it has that lady,” he paused and thought for a moment and said, “Madona!”

“Yes, Coach,” I said. “But she’s just in a small part singing a song and Holden and that girl slow dance to it.”

He continued watching a few more minutes, then said, “Well. Okay. That’s fine. You can show it to the team.”

He stood up, patted my shoulder, held up his forefinger, and said: “Just get all the kids to complete the forms on my desk first. And get a physical. They need a physical.”

“And shoes,” he said, “they’ll need shoes. Tell them to come see me if they can’t get any. And headgear; I already have that for them.”

I said, “Okay, Coach.”

He waddled away to go do something.

I stayed and finished watching Vision Quest. It was how long I would have stayed for practice, anyway.

I did not, not even for a second, think or feel that it was a special moment between Coach and me. He was a man of conviction and intentionality, and after having Coached hundreds of kids he knew how to maintain boundaries. I suspected he was wary of authorizing a film he had not seen, especially for incoming freshmen who, as I knew, could be as young as 11 years old. It turns out that was just the case. Vision Quest had flopped in the box office compared to other hits like The Karate Kid, but when Madona skyrocketed to fame it was re-released as “staring Madonna,” though she only had a one-minute role; Coach had seen his daughter, Penny, watching MTV in their living room, so he only knew Madonna by her video, Like a Virgin, which most wrestlers watched dozens of more times than Vision Quest.

Still, it was one of my favorite moments with Coach, partially because of why he stayed, but mostly because he stood up and walked away and trusted me to do the right thing.

Go to the Table of Contents