Wrestling Hillary Clinton: Part II

“[Jimmy Hoffa’s] mention of legal problems in New Orleans translated into his insistence that Carlos Marcello arrange another meeting with Partin, despite my warning that dealing with Partin was fruitless and dangerous.”

“He wanted me to get cracking on the interview with Partin. In June, Carlos sent word that a meeting with Partin was imminent and I should come to New Orleans. As [my wife] watched me pack in the bedroom of our Coral Gables home, she began crying, imploring me not to see Partin. She feared that it was a trap and that I would be murdered or arrested.”

Frank Ragano, J.D., attorney for Jimmy Hoffa, Carlos Marcello, and Santos Trafacante Jr., in “Lawyer for the Mob,” 1994

My grandfather had been the head of Teamster’s Local #5 since the 1950’s, thirty years total, and was probably the most famous person in Baton Rouge if not all of Louisiana. Most people I knew called him Big Daddy, but he known nationally as Edward Grady Partin, the big, rugged, handsome Teamster leader who was in a Baton Rouge jail on kidnapping and manslaughter charges when U.S. Attorney General Bobby Kennedy and FBI director J. Edgar Hoover freed him infiltrate the Teamster’s inner circle and find something – anything at all – to remove International Teamster president Jimmy Hoffa from power; kidnapping two young children was the “minor domestic problem” Hoffa would quip about for the remaining 11 years of his life.

Big Daddy’s 1964 testimony and Bobby and Hoover’s phrasing of his task reached the supreme court and was followed nationally, not just because it was Hoffa but also because the case was overseen by Chief Justice Earl Warren1, internationally famous for the 1964 Warren Report that mistakenly said Lee Harvey Oswald, a New Orleans native who trained in the Baton Rouge civil air force under the alias Harvey Lee, acted alone when he shot and killed President Kennedy in 1963; and that Jack Ruby, a Dallas night club owner and gopher for Hoffa and the mafia, acted alone when he shot and killed Oswald 48 hours later.

Warren was the only one of nine U.S. supreme court justices to vote against using Big Daddy’s testimony in 1966’s Hoffa versus The United States. His primary reason to reject Big Daddy’s testimony was to protect the U.S. Constitution’s 4th Amendment, hand written and introduced to congress in 1789 by our forefather’s to protect Americans from illegal search and seizure and to ward off a police-state; they wrote:

“The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.“

Warren said that the case should not have reached the supreme court, one of around 50 or 60 out of more than 50,000 petitions from lower courts, each year, saying that the FBI unambiguously violated the 4th Amendment when Big Daddy was asked to find “‘anything illegal,’ or even “anything of interest.'” The case should have been thrown out at the state level by any competent judge. Warren said that Big Daddy was, at the nascence of wireless technology planted by the FBI after securing a warrant, “the equivalent of a walking bugging device,” and that using his word to convict anyone would create a precedence that all future police and courts in the United States could refernce, which he said would “polute the waters of justice.”

In his three-page missive permanently attached to Hoffa versus The United States, Warren presented his case to uphold the U.S. Constitution concisely, then railed against Big Daddy’s character, mentioning the name Edward Grady Partin 147 times and citing specific examples of why he should not be trusted by any rational human who had read the constitution, much less a supreme court judge. Warren seemed flabbergasted that he was the only one stating the obvious; among many things, he wrote:

“Here, Edward Partin, a jailbird languishing in a Louisiana jail under indictments for such state and federal crimes as embezzlement, kidnapping, and manslaughter (and soon to be charged with perjury and assault), contacted federal authorities and told them he was willing to become, and would be useful as, an informer against Hoffa, who was then about to be tried in the Test Fleet case.“

The Test Fleet case was national news in 1962. When Big Daddy stood up from beside Hoffa’s side in court as the secret witness, Hoffa exclaimed, “Oh, God, it’s Partin!” and Big Daddy testified that Hoffa had suggested he bribe a juror in a state-level case monitored by Bobby Kennedy that said Hoffa’s trucking business, named the Test Fleet and held in his wife’s name, violated his fiduciary responsibilities as president of the world’s largest union, the Teamsters trucking union. No bribe ever occurred and no recordings were made; it was Big Daddy’s word against Hoffa’s, and though Big Daddy had a court record of perjuring under oath, his smile and southern drawl and quick qit were so convincing that he convinced the jury to trust him. They deliberated less than four hours before convicting Hoffa of a felony that would, after he lost his appeal to the supreme court, send him to federal prison for eight years.

If Warren was flabbergasted; Hoffa and his team of expensive and high-profile lawyers were shocked, dismayed, and infuriated. Many people suspected Bobby and Hoover of influencing the supreme court, perhaps with the blackmail tactics Hoover notoriously used when he used FBI bugs to recorded politicians and judges in embarrassing situations in their homes, an irony about the 4th Amendment that makes people not being blackmailed chuckle. Hoffa had $1.1 Billion in the Teamster pension account at his disposal, and he launched a media campaign to discredit Big Daddy and get the voting public to demand justice.

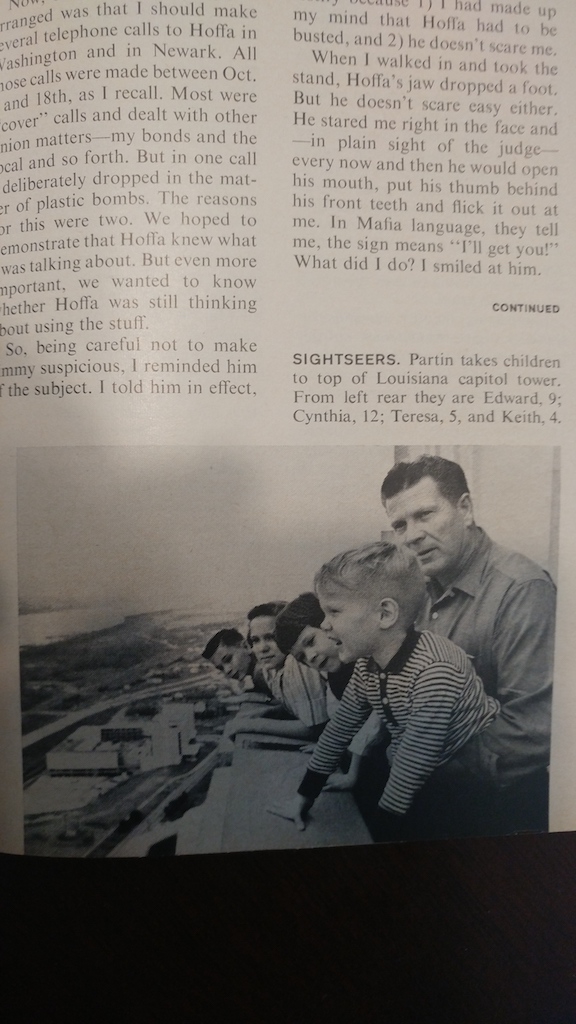

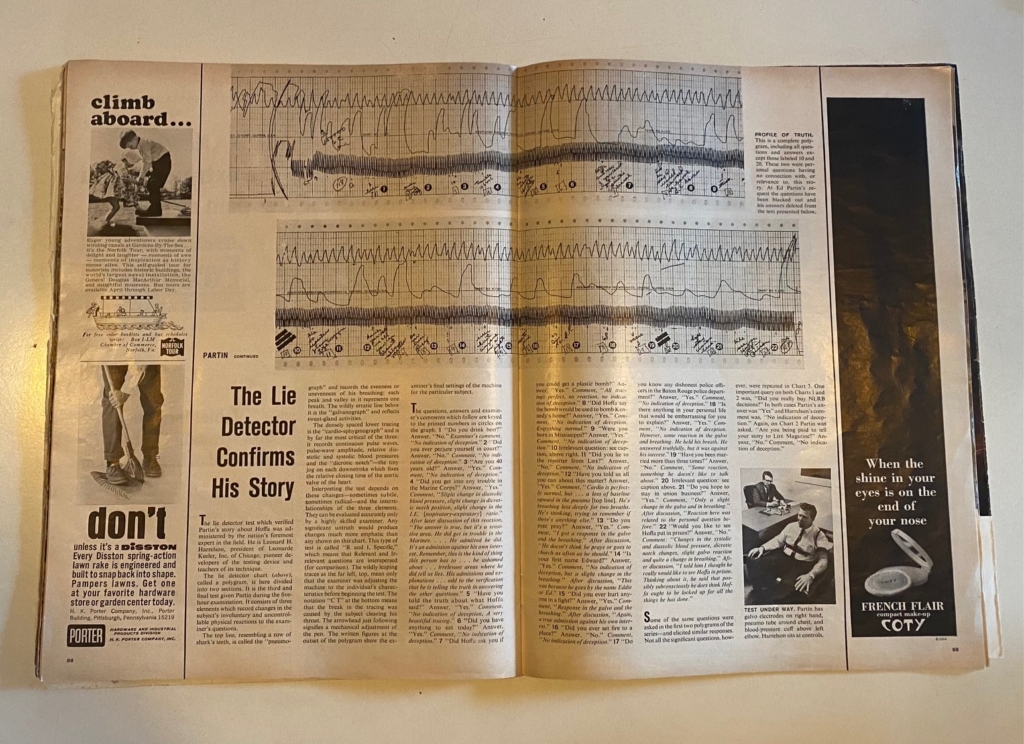

To protect their star witness from deformation by Hoffa’s army of lawyers, Bobby used his connections in the most popular media of the day, and magazines like Look! and Life showcased the Partin family to America. Hoover, ironically a homosexual behind closed doors, plastered a one-page photo of Big Daddy shirtless in his boxing shorts and gloves, smiling his most charming smile, and a two-page photo of him strapped to a lie detector as if in bondage; Hoover published all the wiggly lines of the lie detector results, and though no one but FBI experts understood them, he personally swore that the new technology proved that Big Daddy spoke did not lie when he said that Hoffa suggested he bribe a juror, and that he and Hoffa plotted to murder U.S. Attorney General Bobby Kennedy using military plastic explosives obtained from Carlos Marcello.

Pundits rallied to less avail; like with any government controversy, they pointed to the waste and corruption, saying that the pursuit of Hoffa had been the most expensive and fruitless pursuit of one man by a government in the history of America – something that was may have been true until America targeted President Noriega and Osama Bin Laden – and that the assault on our 4th Amendment was a desperate grab by Bobby Kennedy to stay off embarrassment of him and his big brother, President John F. Kennedy.

People in Baton Rouge, like most people who ignore pundits and government rhetoric, focused on what was important to them, and they were happy to see their names and hometown in national spotlight. Photos of Big Daddy around town stood out: his smiling face supporting the teacher’s union strike when they picketed outside the capital, and his strong pose atop the state capital building, standing in the crow’s nest observation deck and holding a young Uncle Keith in his arms while my dad and aunts Janice, Cynthia, and Theresa peered over the same railing I stood atop once a week, dripping sweat from my plastic sweat suit.

My dad was 9 years old in that photo, and I looked so much like him and we were so close in age that many people mistakenly thought I was him: some old timers called me Ed when I walked by the Teamsters office. When I stood in the crow’s nest high above Baton Rouge, staring at LSU’s Tiger Stadium downriver and the chemical plants upriver, I wasn’t thinking of wrestling Hillary Clinton, I was pondering nature versus nurture.

The issue of Life with my family atop the state capital was shared with the new first family, the Johnsons, who were thrust into the spotlight when President Kennedy was shot and killed only ten months before Big Daddy’s testimony; because of everything going on all at once, all of Baton Rouge focused on that issue, and so did most of the country and much of the world. The media said that Big Daddy was an “all-American hero” for risking his life and the lives of his family to clean up corrupt unions and stand up against Hoffa’s mafia colleagues, men like New Orleans boss Carlos Marcello. The moniker stuck, and Big Daddy’s prestige grew in Baton Rouge because he could defy America’s most powerful man, the mafia, and the constitution of the United States with impunity. For an entire generation, the Partins, more than the Johnsons, were the talk of town.

Big Daddy returned to Louisiana and continued to run the Louisiana Teamsters, and his picture made front page news in Louisiana every month or so. His name came up again nationally when Bobby Kennedy was assassinated in 1968 and Hoffa vanished in 1975, and as part of the almost monthly campaign against organized crime. In 1983’s film “Blood Feud,” people remembered what Big Daddy and Hoffa looked like, and the burly and handsome actor Brian Dennehy portrayed Big Daddy in one of his first major roles, the same year he portrayed the Korean war veteran and sheriff who pursued Sylvester Stallone in Rambo: First Blood, a film about a Special Forces Vietnam veteran with PTSD who shot up a small town with an M-60 after deputy sheriffs drew First Blood.

In Blood Feud, named for the years of intense public battles between Hoffa and Bobby, Robert Blake won an academy award for channeling Hoffa’s rage, Ernest Borgnine portrayed J. Edgar Hoover, and some daytime soap-opera heartthrob whose name I can’t recall portrayed Bobby. Big Daddy was our home-town hero and everyone talked about him more than anyone else in the film, and every time Brian Dennehy was in a new film Baton Rouge people were reminded of his role as Ed Partin.

The Partins were a Louisiana legacy. Half of Baton Rouge had worked for Big Daddy at some point, driving trucks to ship Louisiana’s agriculture products across the country to ships in the ports of Baton Rouge and New Orleans to be sent up the Mississippi river or out the Gulf of Mexico and across the globe. The burgeoning petrochemical industry along Chemical Alley upriver of the capital building depended on Teamsters to ship gas and plastic pellets along the purpose-built I-110 that connected the chemical plants and Baton Rouge airport to the cross-country I-10 that spans from Florida to the Santa Monica pier, passing the port of New Orleans so Teamsters can drop off or load up oproducts that are on every shelf in every town and keep America’s economy afloat. The threat to America’s economy by one man, and his untraceable $1.1 Billion dollar pension fund that was lent to mafia bosses around the country is what had led the Kennedys to starting the Blood Feud.

Like how Hoffa used Teamster money and resources to finance and control Hollywood films, Big Daddy brought the movie industry to Louisiana using his influence and Local #5 dues, then hired Teamsters to drive equipment trucks from one end of I-10 in Hollywood directly to Baton Rouge, a 3,300 mile straight shot. Once there, Teamsters stood by Teamster trailers that housed actors and film-industry union workers, and they got to stand beside famous actors and take photos with them; everyone who had met John Wayne said Big Daddy brought him there, and many locals were tapped to star as extras in films.

The 1988 film “Everybody’s All American,” an epic football tale spanning 25 years of a celebgrated football player’s life, staring Dennis Quaid, Jessica Lange, Timothy Hutton, and John Goodman, was filmed in Baton Rouge the winter two years before it was released, and in it you can see a handful of my classmates and some of my teachers as uncredited extras in a stadium of 10,000 Baton Rouge people dressed up in 1950’s garb; ironically, I was not in the film, because I was with my dad in Arkansas over Christmas, but if you squint at the screen, you can see Lea and a couple of wrestlers cheering in the stands when Dennis Quaid runs for a touchdown.

In one scene, a crowd gathered around the state capital was reshot because of a snowfall so rare in our warm southern city that, though surreal and magical, would have been too fantasatstic for a serious film set in the warm south, where people wore short sleeve football jerseys and rode around in convertibles even in autumn. But it was because of the rare snowfall that everyone in town talked about the first shooting and their small part in it, and Everybody’s All American was still daily chatter by the time I wrestled Hillary Clinton. The film’s name was an obvious shout-out to Big Daddy, who, because of Bobby and Look! and Life, many people mistakenly thought was an all-American hero. No one cared about details like whether or not Big Daddy was trustworthy.

I never talked about my Partin family. I was one of the few people who knew that Big Daddy was a rapist, murderer, thief, adulterer, lier, bearer of false witness, racketeer (I wasn’t sure what that meant, but I knew it could send you to prison), embezzler, drug addict, betrayer of teammates, collaborator with Fidel Castro, and a man who, according to Mamma Jean, alerted her to his lifestyle when he stopped going to church on Sundays. She was a woman who could quote the bible and the U.S. Constitution, especially the 5th Amendment and Warren’s Miranda Rights that remind us we have the right to remain silent, a right few people practice with her diligence.

It was because of Big Daddy that I asked to be assigned to the 82nd Airborne, my ultimate test of nature versus nurture. The 82nd sported an patch on their left shoulder with two A’s under an Airborne tab that stand for the All Americans, a name given to them when they were created as the 82nd Infantry to fight what was called The Great War before we began calling it World War I.

The Great War began only a generation after the civil war, something I thought about every time I ran up and down the state capital and saw the old War School and pot marked buildings around downtown. Brother fought brother, something I never understood; neither did some leaders when America entered The Great War, and one of them noticed that the newly formed 82nd was the first time in American history that a military unit had soldiers from every one of the United States; hence, the moniker All Americans. Someone in a higher power wanted to inspire unity among former enemies, and for the first time the All Americans went to war in Europe, leading to Germany’s surrender in 1919.

WWII began 20 years later. Hitler began winning battles with German paratroopers; parachutes were new, and the joke back then was who, in their right mind, would jump from a perfectly good airplane? America’s answer was the 82nd Infantry, and they reactivated the unit and made the All Americans America’s first paratrooper unit, the forefathers of our special forces. An Airborne tab was added above the AA on their shoulder patch, and they jumped behind enemy lines five times in WWII, suffering losses of almost all in order to hold a line for more troops to arrive, and they are credited with turning the tides of major battles like The Battle of the Budgle against Hitler’s Panzer tank division in occupied Belgium and Luxenburg, and the Anzio beachhead assault into Mussolini’s Italy.

They were so feared by the Germans that to this day my future unit, the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment of the 82nd Airborne Division, was named “The Devil’s in Baggy Pants” after a German officer documented the specialized pants that had bulging pockets to hold the extra ammo they carried, knowing they would be so deep behind lines they wouldn’t be resupplied. The Nazis had assumed no one would be able to penetrate their heavily manned and fortified defensive positions ahead of the Anzio beachhead assault, but one officer was so surprised by the 504th’s tenacity that he wrote:

“American parachutists…devils in baggy pants…are less than 100 meters from my outpost line. I can’t sleep at night; they pop up from nowhere and we never know when or how they will strike next. Seems like the black-hearted devils are everywhere…”

Today, the 82nd Airborne is the president’s quick-reaction force: 12,000 paratroopers on call to deploy anywhere in the world within two hours without congressional approval for up to thirty days. In the 1980’s, the 82nd Airborne was national news every year or so: they jumped into Panama in 1989 and Grenada in 1985, landed in the Dominican Republic in 1983 and Honduras in 1979, and before that they were one of many Vietnam units in the news throughout the 1960’s and 70’s. Their mission has always seemed to be parachute in, take heavy losses, and capture airports or beachheads and hold that line until reinforcements arrive; you’d have to be crazy to volunteer for that, or have something to prove.

The All Americans were as famous as Big Daddy was when I was a kid. They were celebrated by actors as big as John Wayne – a little guy compared to Big Daddy – whose photo with Mamma Jean sat on her dresser; the Partins knew John Wayne from when he starred civil war movies filmed around Louisiana and Mississippi’s plantations, shown wearing their maroon berets, coincidentally the color of the Capital Lions singlets. But, as a kid who knew about John Wayne and had seen all his movies, what stuck in my mind more than the maroon beret was the 82nd’s nickname, The All Americans, and the sarcastic taunt of being an “all-American hero” Jimmy Hoffa used about Big Daddy in news and in his autobiography. I figured that if I wanted to test nature versus nurture, there was no better way than to join the real All Americans and see what I could do.

The Christmas and New Year of 1989-1999, when I was already signed up for them and training to wrestle Hillary Clinton, the 82nd was on television and newspaper news every day, because President Bush Senior had sent them to Panama as a continuation of President Reagan’s war on drugs that dominated news in the 80’s. The 82nd flew to Panama overnight in a fleet of C-130’s (nicknamed the Hercules) and C-141 Starlifters skimmed over the jungle trees at 4am, then piled out of the side doors and filed the air with parachutes, machine guns, and testosterone. They overtook Panama within a few hours and surrounded President Noriega’s compound until other American forces joined, landing in the airport the 82nd had captured.

Over Christmas and New Years, I skipped rope to my playlist with Van Halen’s “Jump!” and “Panama,” and watched international news follow the 82nd and two platoons of .50 cal machine gunners from the 504th anti-armor company, and show them holding Noriega captive by surrounding his compound for weeks. To capture Noriega alive, guys I’d grow to know well brought in speakers big enough to host a music festival and blared heavy metal 24 hours a day, depriving Noriega and his personal guard of sleep with songs taken from Van Halen’s 1985 album played all day and night for weeks, songs that so ironic that not even Hollywood could contrive the scene, like “Jump!” and “Panama.” I suspected Noriega was the only person on Earth other than David Lee Roth who knew the lyrics to Panama as well I as did.

The news was so detailed that we noticed no 82nd paratroopers died, yet a handful of the then newly-known Navy SEALS did, and so did two Delta Force anti-terrorism commandos, a team we suspected existed after Chuck Norris’s cheesy 1986 film, “The Delta Force,” the first in an equally cheesy three-part franchise based, in part, on the 1985 hijacking of TWA Flight 847 and the 1979-1980 Iran Hostage crisis where 53 Americans were held aboard an airplane for 444 days, part of the reason Carter lost to Reagan in 1980, in addition to the resulting oil crisis that led Teamsters to lining up for miles to fill their rigs; it’s funny the things I remembered from listening to Big Daddy and the Teamsters as a kid, and those memories filled my mind as I watched news report on the 82nd every day as 1989 transitioned to 1990. Every day, I pondered my delayed-entry contract, which said I’d have a choice to withdraw at any point up until I was scheduled to depart six months later, but I couldn’t imagine anything that would change my conviction that I would be an All American, if only as a stepping stone to whatever was next. I jumped rope a bit faster, did an extra set of pushups or two, and ran another lap around the track when I thought I was too fatigued to continue.

On 16 March 1990, two weeks after Hillary Clinton broke my finger, I rode a Honda Ascot 500cc shaft-drive motorcycle to my grandfather’s funeral, a small and low-maintenance machine that a teammate lent me and that got around 55 miles per gallon and let me take trips to New Orleans, where I performed card tricks near Jackson Square for tips, modifying my methods to accommodate my broken left finger.

My two left middle fingers were buddy-taped; for the funeral, I applied two fresh strips of bright white cloth tape, not because the fingers still needed it, but because I liked the way it looked and how it made me feel, and I hoped someone would ask about it so I could tell them about wrestling and what I was doing after I graduated high school. Though season was over, I still did pushups throughout each day, favoring my right arm and doing one-handed pushups to prepare for basic training a few months later.

I was wearing a white helmet airbrushed with blue letters that said “c/o 1990?,” a jab at overzealous seniors who wore shirts that said, “Class of 1990!” and a form of psuedo-apathy about my abysmal grades from 9th and 10th grade that made my graduation uncertain; had it not been for Coach asking me to try my best in academics, I probably would have had to attend summer school and forfeit my army contract, but I would graduate with a 1.87/4.00 GPA and make the requirement by 0.37 points; my senior GPA was a respectable 3.20/4.00, and I was proud of that. I knew that I had failed out of ninth grade, but given that everyone in my family was in prison I thought I was a decent kid doing the best I could; my senior year added conviction that I could do anything I began in earnest. I learned to ignore teachers who had advice to offer; they were, to me, just like all other adults ignorant of what happens behind closed doors.

I sported my cherished but gaudy fuzzy orange letterman jacket with blue sleeves a big blue letter B on the left chest, and I had meticulously adorned the orange fluff over my heart with 36 small gold safety pins, grouped in clusters of five for easy counting. The letter B had an admittedly awkward looking wrestling letterman pin, the one modeled after an old Greco Roman statue with one man down and the other grasping him from behind. For cross-country track, I had Mercury’s winged feet; for chess, a rook; and for theater, the comedy and tragedy faces of theater. Though I swam for practice, catching a ride to Catholic High’s pool, I was an abysmal swimmer who sank like a rock and didn’t letter.

Across the back of my jacket was a sprawling black-colored “Magik” that I had splurged on and had embroidered at a t-shirt and nick-knack shop on Florida Boulevard in a run down strip mall walking distance from Belaire, nicknamed Little Saignon because of the flood of Vietnamese who moved there after Saigon fell in 1975; like southern Louisiana, southern Vietnam was a humid, muggy agricultural and seafood region that the French had colonized and spread foods like French baguettes and pate, so the muggy port town of Baton Rouge – Red Stick in French – was a logical move for thousands of Vietnamese who had supported America and had to flee the communist takeover. To blend in, and after a few of their kids dressed as GI Joe for Halloween trick-or-treating were shot by Vietnam veterans living in Belaire’s cheap apartments, the Vietnamese-owned businesses in strip malls along Florida Boulevard began selling shirts with Airborne wings and berets that said things like “Death from Above” and “Kill ’em all, let God sort ’em out,” and not checking ID’s when selling cigarettes and cheep beer; in the ninth grade and tenth grade, I, like most of my buddies back then, spent a lot of time there.

I stopped drinking alcohol beginning in 1986, when Big Daddy was released from prison and began spending more time with me at Grandma Fosters; he never drank because, he said, it loosened lips and made people say things they wouldn’t want anyone to know. But Lea and I often hung out at the heavy metal t-shirt shop that also sold glass tobacco pipes and ornate desk lamps that most kids knew were bongs, and I dropped quarters into a few stand-up video games they kept near the cigarette machine and listened to whatever music they played, which is how I first heard Van Halen’s 1984 album aptly called “1984” and Guns-N-Roses 1988 album called “Appetite for Destruction.” They advertised their bon-migh sandwhiches as “Vietnamese Po’Boys,” and catered to kids from Belaire High School with the latest heavy metal and hip hop bling. Below my black embroidered nickname was a hand-sized black and white skull wearing what looked like a magicians hat, but was actually a character of Slash, the guitarist for a new band called Guns and Roses, who wore a top hat he stole from a Los Angeles thrift store wherever he went and that became his signature look on MTV. I was the first kid in school who knew trivia about Guns-N-Roses, and the patch made me stand out among the stereotypical jocks who also wore letterman jackets.

I spent all of my money on Pac-Man and Galaga, the embroidery and Slash patch, and a Vietnamese Po’Boy to celebrate not cutting weight for a while, so I didn’t have enough to pay the tailor to add the skull and top-hat. Lea lent me a sewing kit, and I painstakingly hand-sewed the patch under my nickname. Sometimes, real life is more fantastic than fiction; the patch was prophetic, because I’d learn that – though not known by news crews and therefore not known in America – that when the side doors of my future team’s C-141 Starlifter opened and the hot muggy air whooshed inside, someone slipped a Guns-N-Roses cassette into the speaker system and blared Slash’s quintessential guitar riff; for the first time, 123 paratroopers on a one-way trip heard Axl Rose’s wailing voice scream “Welcome to the Jungle.” I would look back on that jacket and everyone at Big Daddy’s funeral and feel that if there was such a thing as fate or an answer to life’s mysteries, it was served alongside a Vietnamese po’boy off Florida Boulevard and buried with my grandfather in Greenwood Funeral Home.

I slowed the motorcycle down and rode along the shoulder of Airline Highway, the small engine barely audible over the traffic jam of cars and idling 18 wheel trucks headed towards Greenwood Funeral Home. I slowly braked onto the grass beside a paved parking spot and as close as police would allow, turned off the bike, and draped my helmet on the handlebars and my jacket on the seat.

There was a slight rumble from idling 18 wheelers on Airline, and a breeze that smelled of springtime azaleas planted along the cemetery road to showcase red flowers in March. The breeze made the pins on my jacket tinkle like tiny wind chimes, though not quite: the chimes on Auntie Lo and Granny’s porches were hollow and echoed when they rang, but the sound of my small solid pins died flat. Though flat sounding when only a few, the tinkle from so many of them created an illusion of chimes that rang like church bells in my ears. I paused to listen to them, proud of how many there were, and realizing how I would have been surprised by them only a year before. Time flies, and a lot had happened in that year.

My face shone from lingering pride at media coverage and a small award from Coach and the team that they presented in front of all 383 Belaire seniors. Most athletic. Coach’s award. A few others. We had just lost three of our elected senior representatives to a drunk driving accident when they were thrown from the back of an open pickup truck and split their heads open on Florida Boulevard, so everyone was emotional and teachers wanted to focus on something positive; my using a helmet despite Louisiana’s lax laws was mentioned. When Coach stood beside me in front of everyone and looked up into my eyes and said, “We love you, Magik,” I hugged him and rested my head atop his thin grey hair and sobbed. So many kids applauded my brief moment on stage that I was still riding the high, and after all of that attention I was unimpressed by the crowds of people and reporters clustered outside of the funeral home.

I glanced at the rows of police and federal marshals dressed like Men In Black wannabes, a lingering effect of men loyal to Hoover’s archaic dress code; their concealed weapons and bulky wireless communications gadgets so obvious to me that I wanted to show them how a magician hid doves and Coke bottles before a stage show; as a kid, I had imagined that Mamma Jean was followed by diligent Johova Witnesses wearing black suit and ties with pockets bulging from the bibles they carried door to door. Walter Sheridan, head of around 500 FBI agents on the Get Hoffa task force but a man who work casual business suits that blended in more, described the best FBI technology back then as a way to explain why Big Daddy’s testimony against Hoffa was unrecorded: they tried to put the device on him, but it was as big as “a king-size pack of cigarettes,” and it was noticeable when Big Daddy’s muscles bulged through the tailored business suit he wore when meeting with Hoffa.

Anyone who knew anything knew how to spot a wireless device, which meant you should know how to hide one. But I kept silent and strolled past them and walked up to Aunt Janice, who was waiting by the double doors to great family and welcome them in. I was the last one. She bent down to hug me, and we went inside.

Besides Grandma Foster, Big Daddy’s mother and the only other tiny person in our family, there were twenty or thirty Partins, mostly from Big Daddy’s marriage after Mamma Jean, who stayed nearby at her sister’s house and was waiting for us to join later. There must of been two hundred people I didn’t know, but there were a handful I either knew or recognized. The former Baton Rouge mayor was there, and so was the entire Baton Rouge police department, reporters from every major newspaper, a hell of a lot of huge Teamsters, a gaggle of FBI agents including two wearing the Men In Black garb, Walter Sheridan, and a surprisingly long lineup of aging brutes from the 1954 LSU football national champion team who had served as Big Daddy’s entourage in the 60’s.

Billy Cannon, a veteran of the 1954 team and LSU’s first Heismann Trophy winner, was there. He was a two time All American, former pro for the Houston Oilers, and the biggest celebrity on the biggest float in the Spanish Town Mardi Gras parade. Growing up, I saw Billy’s handsome smiling face was on billboards all along I-110, between downtown and his home in Saint Francisville, his bright white smile advertising his dental business on their way to and from work in the chemical plants north of downtown. When Hollywood filmed Everybody’s All American, people in Baton Rouge felt it was a movie about Billy; the fictitious film was based on a Sports Illustrated writer’s book of the same name who would have remembered Billy, so there’s probably some truth to that, and part of the reason they set the film in Baton Rouge. Of course Billy would be Big Daddy’s pallbearer; it made Big Daddy seem larger than life, even after death.

After everyone finished speaking, Billy, Doug, Kieth, Joe, and two Teamster beasts I didn’t recognize heaved to pick up Big Daddy’s casket and carry it past all the reporters to be laid in Greenwood cemetery. With all of those celebrities at the funeral home, it’s no wonder no one asked about my letterman jacket or buddy-tapped fingers, not even the reporters and television crews supposedly focusing on things like that. They knew Walter by then, because he had been tapped to represent NBC as a trusted news correspondent to cover New Orleans district attorney Jim Garrison’s highly publicized trial against Charles Shaw, to this day the only court case against someone suspected of killing president Kennedy, so all of those reporters could have had their facts checked. Instead, the New York Times listed me as one Edward Grady Partin Senior’s surviving grandchildren and mistakenly said he had “great-grandchildren,” but I was the second oldest and knew all of my cousins from both Big Daddy’s marriages and a few suspected from his extramarital affairs, proving that even the NY Times makes mistakes, just like Life magazine, The Warren Report, and the Grand Jury that declined pulling Big Daddy into Garrison’s trial.

Only Walter Sheridan asked about my fingers; but he was a senior FBI director who reported directly to J. Edgar Hoover and Bobby Kennedy, so he was probably good at noticing details other people overlook. Most people wouldn’t recognize Walter; he had a small role in “Blood Feud,” too, where the actor who portrayed him slapped Big Daddy to show how tough the FBI could be. Walter would write that when he met Big Daddy, he was shocked at how much bigger he was in person than Walter had imagined, even after hearing how Teamsters and mafia bosses were intimidated by him. He’d write that in all of his years overseeing informants for the mafia, every single one wanted him to promise anonymity, and that Big Daddy was the only one brazen enough to want the spotlight; when Hoffa signaled a death-hit on Big Daddy that day in court, Big Daddy simply smiled that charming smile as if he didn’t have a worry in the world.

Coincidentally, Walter Sheridan looked like Jimmy Hoffa; as a kid, I was confused by why his photo was on both the front and back covers of his book, but it turns out that the blurred front cover was supposed to be Jimmy Hoffa. Hoffa vanished on 30 July 1975, when I was just a toddler, so of course I had never met him, but Walter had known my family for almost 25 years and I had seen him once or twice. He managed the federal marshals Hoover had personally selected to follow and protect us after Hoffa’s threat, and he seemed interested in anything a Partin said or did.

When he asked about my buddy-taped fingers I told him I broke my finger wrestling in city finals. I didn’t use Hillary’s name, because I didn’t know yet how funny it would sound if I said Hillary Clinton broke it; I spent a lot of summers and holidays with my dad in Arkansas, but I wouldn’t know that Bill Clinton was governor and that his wife was named Hillary for another two years. Walter congratulated me and seemed interested in whatever I had to say, and I talked his ear off about how I was headed to the 82nd. I only stopped because the funeral began.

The mayor and the football players said a lot of words, and so did a few of my younger cousins. Tiffany, Janice’s daughter and the only cousin older than I was, spoke. She was 18, almost six feet tall, and, like my dad, Janice, and me, had Mamma Jean’s dark brown eyes instead of Big Daddy and Grandma Foster’s sky blue eyes. Tiffany was gorgeous, like Mamma Jean and Janice, and had been homecoming queen in a Houston high school. She and all of my aunts and most of my cousins lived near the house Bobby bought for Mamma Jean in exchange for her silence. Tiffany was a remarkable public speaker, and she held the hundred or so people listening captive. She told stories about Big Daddy’s sweet smile and dotting affection for his family, and everyone was already in tears when Jennifer took her turn.

Jennifer was Cynthia’s oldest daughter and a high school sophomore in high school, but she was still taller than I was. Jennifer had written a letter preparing for the funeral in January, when we knew Big Daddy only had months or weeks left to live. She read it in front of everyone and put it in Big Daddy’s pocket before they closed the casket. Aunt Cynthia would send a copy to Doug after the funeral, scribbling a note to explain it and saying:

Uncle Doug,

Jennifer, my daughter, wrote this in school almost 2 months ago. She put it in Daddy’s pocket, along with Janice’s letter.

In his autobiography, Doug photocopied Jennifer’s hand-written letter, which said:

I never really knew my grandfather. His whole life is a mystery to me. For he ended up being a bother to Hoffa and a good friend to Kennedy. The only way I learned about his part was from reading Life magazine and books. Now time is flying by so very fast, and I am afraid I will never look at his tender and loving eyes again. For he is extremely ill and near death. Lord, when he dies, his new life will begin. So give him mercy, for he tried his best. I know he’ll go to the heavens above and look down upon me and feel my love.

To Big Daddy from your loving granddaughter,

Jennifer

January 1990.

Jennifer sobbed as she read her letter, and when she finished everyone was bawling; not even I wanted to point out the understatement of being a “bother” to Hoffa, nor did I want to tell my cousins that the Big Daddy they knew from Life magazine and books wasn’t the one I knew from growing up with him in Baton Rouge rather than with our close-lipped Mamma Jean in Houston. She and Tiffany were the only two of about a dozen of my cousins to speak. I did not because no one asked me to, and neither did my cousin, also named Jason Partin, a football star for the Zachary Broncos who was younger than I was but already over six feet and around 190 pounds; his father, Joe Partin, Big Daddy’s little brother, was Zachary’s football coach and principal and the only Partin not a Teamster. Jason, Uncle Joe, and I had mumbly southern accents back then, unlike Big Daddy’s charming drawl or our female cousin’s soft southern belle appeal, which may be why none of us were asked to speak.2

After the funeral, when most people got up and flocked around Billy and the aging Tigers, I leaned over and told Walter – who didn’t seem to care about football – what Edward Partin’s final words were, and I chuckled as I said it: “No one will ever know my part in history.” He agreed that it sounded funny when said out loud, and that my grandfather was probably right.

Not satisfied, I added, “He taught me how to throw a punch.”

Walter was unfazed.

“It’s all about your stance,” I said. “And long arms,” I added, stretching out my right arm to demonstrate.

“It lets you surprise someone,” I said, as if I had actually ever punched someone.

Walter said nothing, but he had a kind smile and I continued.

“And stay calm,” I said, holding up my knobby right forefinger to emphasize the point.

I lowered my finger and said, “Pay attention to your heartbeat.”

With a tone of voice that probably conveyed the conviction I felt, I stated, “That’s how he beat the lie detector.”

I smiled, letting Walter know I knew that secret. Hoover, when he was Walter’s boss, had put a photo of Big Daddy, strapped to a lie detector machine and surrounded by federal scientists in white lab coats, in Life Magazine. The photos of Big Daddy and his lie detector results and Hoover’s analysis took up two entire pages of a magaizine so big that the open issue covered an entire high school desktop. Everyone had seen it, but only the family and – I assumed – Walter knew that Big Daddy could fool any lie detector test by remaining calm and practicing whatever he wanted to say so that no machine could detect the little hiccups between feelings and thoughts and words, like how a wrestler practices a move until it’s a habit.

Walter smiled back, presumably letting me know that I shared a secret with the highest levels of federal agencies, and that’s when I knew I was ready for whatever the 82nd could throw at me.

I left the funeral and paused by the Honda Ascot to listen to the tinkle of my 36 safety pins. I removed the buddy-tape and put the strips in my front pocket, took a deep breath of azalea air, donned my letterman jacket, straddled my motorcycle, and smiled. I was emancipated, a legal adult and able to do anything I began in earnest. I may have lost a battle to Hillary Clinton, but I had won the war of nature versus nurture. I was free. I put on my helmet and started the motorcycle and rode along the now empty Airline Highway without worrying about where I was headed.

I left Louisiana two months later and began basic training in Fort Benning, Georgia, home of the U.S. infantry and Airborne schools, ready to join the 82nd Airborne in Fort Bragg, North Carolina. Unlike John Wayne and Big Daddy, I was going to be a real All American.

Go to the Table of Contents

- Chief Justice Earl Warren mentions Big Daddy 147 times in his three page missive attached to Hoffa vs The United States; my grandfather’s disripute was public knowledge, which confused and infuriated Jimmy Hoffa, and is why he, his lawyers, and many pundits believe Bobby Kennedy or J. Edgar Hoover influenced the supreme court to weaken America’s 4th Amendment and send Hoffa to prison.

This is an excerpt from Warren’s missive:

“This type of informer and the uses to which he was put in this case evidence a serious potential for undermining the integrity of the truthfinding process in the federal courts. Given the incentives and background of Partin, no conviction should be allowed to stand when based heavily on his testimony. And that is exactly the quicksand upon which these convictions rest, because, without Partin, who was the principal government witness, there would probably have been no convictions here. Thus, although petitioners make their main arguments on constitutional grounds and raise serious Fourth and Sixth Amendment questions, it should not even be necessary for the Court to reach those questions. For the affront to the quality and fairness of federal law enforcement which this case presents is sufficient to require an exercise of our supervisory powers.

Warren reiterated Big Daddy’s history to his fellow justices again and again, with the frequency and force of Hillary’s kicks, yet Warren did not break through to his peers. I don’t know why. Here’s a taste you can sample and ponder how anyone believed Big Daddy:

“Here, Edward Partin, a jailbird languishing in a Louisiana jail under indictments for such state and federal crimes as embezzlement, kidnapping, and manslaughter (and soon to be charged with perjury and assault), contacted federal authorities and told them he was willing to become, and would be useful as, an informer against Hoffa, who was then about to be tried in the Test Fleet case. A motive for his doing this is immediately apparent — namely, his strong desire to work his way out of jail and out of his various legal entanglements with the State and Federal Governments. And it is interesting to note that, if this was his motive, he has been uniquely successful in satisfying it. In the four years since he first volunteered to be an informer against Hoffa he has not been prosecuted on any of the serious federal charges for which he was at that time jailed, and the state charges have apparently vanished into thin air.

↩︎ ↩︎ - On 11 March 1990, The Baton Rouge Advocate reported:

Edward Grady Partin, a teamsters’ union leader whose testimony helped convict James R. Hoffa, the former president of the union, died Sunday at a nursing home here. Mr. Partin, who was 66 years old, suffered from heart disease and diabetes.

Mr. Partin, a native of Woodville, Miss., was business manager for 30 years of Local 5 of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters here.

He helped Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy convict Mr. Hoffa of jury tampering in 1964. Mr. Partin, a close associate of Mr. Hoffa’s, testified that the teamster president had offered him $20,000 to fix the jury at Mr. Hoffa’s trial in 1962 on charges of taking kickbacks from a trucking company. That trial ended in a hung jury.

Mr. Hoffa went to prison after the jury-tampering conviction. James Neal, a prosecutor in the jury-tampering trial in Chattanooga, Tenn., said that when Mr. Partin walked into the courtroom Mr. Hoffa said, ”My God, it’s Partin.”

The Federal Government later spent 11 years prosecuting Mr. Partin on antitrust and extortion charges in connection with labor troubles in the Baton Rouge area in the late 1960’s. He was convicted of conspiracy to obstruct justice by hiding witnesses and arranging for perjured testimony in March 1979. An earlier trial in Butte, Mont., ended without a verdict.

Mr. Partin went to prison in 1980, and was released to a halfway house in 1986. While in prison he pleaded no contest to charges of conspiracy, racketeering and embezzling $450,000 in union money.

At one time union members voted to continue paying Mr. Partin’s salary while he was in prison. He was removed from office in 1981.

Survivors include his mother, two brothers, a sister, five daughters, two sons, two brothers and several grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Like The Warren Report and Life Magazine, The New York Times is sometimes mistaken: Big Daddy had no great-grandchildren yet. I was his second oldest grandson, and I was only 17 and I knew my cousins from both marriages and a few suspected from possible extramarital affairs – he was exceptionally handsome and charming – though I didn’t see any of them at the funeral. ↩︎