Wrestling Hillary Clinton: Part I

But then came the killing shot that was to nail me to the cross.

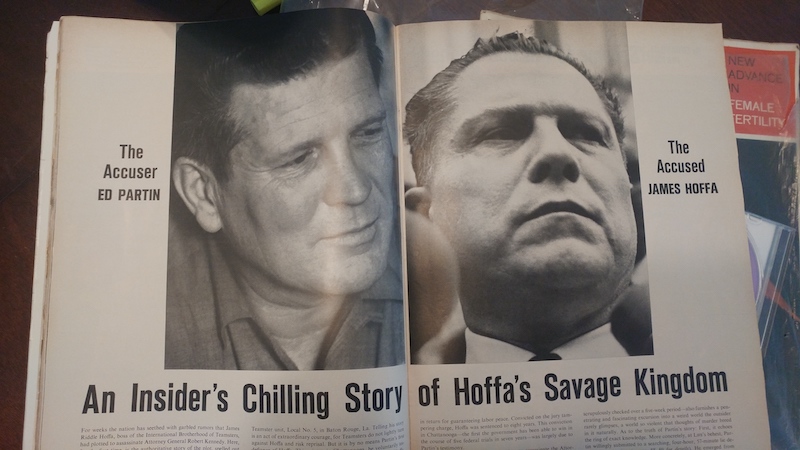

Edward Grady Partin.

And Life magazine once again was Robert Kenedy’s tool. He figured that, at long last, he was going to dust my ass and he wanted to set the public up to see what a great man he was in getting Hoffa.

Life quoted Walter Sheridan, head of the Get-Hoffa Squad, that Partin was virtually the all-American boy even though he had been in jail “because of a minor domestic problem.”

– Jimmy Hoffa in “Hoffa: The Real Story,” 19751

I’m Jason Partin. My father is Edward Grady Partin Junior, and my grandfather was Edward Grady Partin Senior, the Baton Rouge Teamster leader famous for infiltrating Jimmy Hoffa’s inner circle in 1962. His surprise 1964 testimony, the sole reason Hoffa was convicted of jury tampering and sentenced to eight years in federal prison, was ten months after President Kennedy’s assassination.

My family was showcased across national media alongside the new first family, the Johnsons, and my grandfather was shown to have been part of a bigger plan; his testimony thwarted Hoffa’s plot to assassinate President Kennedy’s little brother, U.S. Attorney General Robert “Bobby” Kennedy. Because of obvious retaliation by 2.7 Million Teamsters loyal to Hoffa and the mafia families who depended on funding from the $1.1 Billion Teamster pension fund, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover assigned federal marshals to protect my family 24 hours a day. The media said that by risking his life and the lives of his family to stand in front of a jury, my grandfather was an all-American hero.

In 1983, seven years after Hoffa vanished from a Detroit parking lot, Edward Partin Senior was portrayed by Brian Dennehy in the movie Blood Feud. Producers chose actors to match the physical appearances America knew back then, and directors coached them to fit countless television and media appearances. Robert Blake won an academy award for “channelling Hoffa’s rage,” and a daytime soap opera heartthrob portrayed Bobby Kennedy. Brian was less famous than my grandfather back then, but he was an up-and-coming star known for his “rugged good looks,” green-blue eyes, and charming smile, and he could convince viewers that he fit a famous line from Hoffa’s second autobiography, penned while in prison and released a few months before he vanished, that summarized my grandfather: “Edward Grady Partin was a big, rugged guy who could charm a snake off a rock.”

(Coincidentally, Brian’s break-out role followed Blood Feud later that same year, when he co-starred alongside Sylvester Stallone in another film with blood in the name, “Rambo: First Blood.” Brian was the sheriff and Korean war veteran who took no nonsense and led the manhunt against Rambo, a Vietnam Special Forces veteran with PTSD and a huge knife, who had escaped into the mountains around the sheriff’s small town. Over the next few decades, he won accolades for portraying big, rugged men who could charm audiences with his smile.)

Everyone in Baton Rouge called my grandfather Big Daddy. He watched Blood Feud from his cushy Texas federal penitentiary cell on a surprisingly large color television. He thought Brian did a fine job of portraying him, and that Robert Blake nailed Hoffa. I never asked what he thought of Rambo.

Thirty years after Blood Feud, Big Daddy was portrayed by the burly Craig Vincent as “Big Eddie” Partin in Martin Scorsese’s 2019 opus about Hoffa, The Irishman, based on a 2014 memoir by Frank “The Irishman” Sheenan, a Teamster leader who knew Big Daddy well and claims to have killed Hoffa on behalf of the mafia. The body’s never been found, and the FBI case is still open, but Frank sounded convincing. By then, most people had forgotten what Big Daddy looked and sounded like, and Scorsese said he was making a film for entertainment, not as a documentary, so he didn’t need to find actors who matched the original characters.

Scorsese raised $270 Million and hired a long list of Hollywood’s most famous actors know for gangster films, like Al Pacino, Robert DeNiro, Joe Pesci, and about a dozen others. Craig was chosen to portray Big Daddy because he had worked with Scorsese before, playing a big, brutal, thug in alongside Pacino and Pesci in the Las Vegas mobster film Casino. Scorsese eliminated a chapter of The Irishman centered around Audie Murphy, President Nixon, and Big Daddy; downgraded Big Daddy’s role to a minor one; and changed his southern drawl to match Craig’s northeastern Italian accent.

Craig’s original screen time was 20 minutes, but it was edited down to 5 minutes to squeeze it in to The Irishman’s whopping 3 hour and 29 minute format, an ambitious length for modern attention spans, but still shorter than 1983’s Blood Feud. Despite it’s formidable size, The Irishman sold out theaters until Covid-19 shuttered public spaces, then it set global streaming records on Netflix for two years of the pandemic.

Millions of people all over the world got a simplified glimpse at Big Daddy’s small part in history. In one scene with all the famous actors together, Scorsese lowered the camera angle and placed Big Eddie behind the big names, exaggerating his size and making him loom large over people who didn’t see it that way. I believe that Big Daddy, who died in 1990, would have appreciated how he was portrayed.

Big Daddy had known Frank and all the other characters well for more than ten years, but he never discussed them beyond what was already public in Look!, Life, movies, and the 1966’s supreme court case, Hoffa versus The United States. And he never answered questions about Audie Murphy or President Nixon; he just smiled his charming smile, as if he knew the funniest joke in the world that he’d never share with anyone.

There are dozens of Jason Partins on the internet. When I began writing this memoir in 2019, shortly after Craig researched his role and we spoke for a few hours, I Googled my name for the first time and saw that a few Jason Partins were criminals, a few were people typical in anyone’s town, and one was an aging mixed martial arts competitor who coincidentally looked like a younger version of me. One was – and is – my second cousin, Jason Partin. He’s my grandfather’s nephew and a year younger than I am. That Jason was the football star of the Zachary High School Broncos when we were kids in Louisiana and I was wrestling with the Belaire High Bengals. He went on to play for Mississippi State University, and he currently owns the largest physical therapy treatment center in Baton Rouge. Today, his smiling face looks down from the Lamar Advertising billboards that line I-110 between downtown Baton Rouge and Zachary.

I’m the Jason Partin listed by the United States Patent and Trademark Office as an inventor on several patents as either Jason Partin or Jason Ian Partin. When I began writing this, I was the smiling Jason Partin dressed in a suit on two university’s web sites. I ran a hands-on innovation laboratory called Donald’s Garage, named after Donald Shiley, a mechanical engineer who co-invented of the world’s most successful heart valve in his home garage after work. I designed and led engineering classes at The University of San Diego’s Shiley-Marcos School of Engineering, and I was an advisor for the University of California at San Diego’s entrepreneurship program in what they called The Basement. Both sites used the same professional head shot, which still floats around the internet but is outdated (I have much less hair now, and the thin gray only has hints of the auburn hair I began to loose in the early 2010’s). On the side, I led physics project-based learning at San Diego’s High Tech High School, a public charter school a few miles from Donald’s Garage.

I’ve never discussed my family history with anyone I do not know well and trust, which means I’ve never discussed it with most professional colleagues. When you grow up in a family like mine, you learn to take secrets to your grave.

There were a few other Jason Partins listed as inventors on patents for a range of gadgets, but all of my patents are for medical devices, implants, and technologies that help heal bone fractures and repair soft tissues. Most are focused on small bones and joints, like the facet joints spinal vertebra, ankles and toes, and wrists and fingers. No photo accompanies patents. I haven’t invented anything since I began loosing my hair and working with universities and nonprofits to facilitate hands-on learning and entrepreneurship in public schools.

Like Donald Shiley, I never completed a PhD. I’m one of the few engineering and physics instructors in America without that piece of paper. Donald’s Garage is in a small private Catholic university with around 6,000 students, small class sizes, and a tuition of $56,000 or so per year; The Basement is at one of California’s largest state universities, with around 80,000 students, classrooms that could hold all 300 of my high school’s seniors, and a tuition of $8,900 or so. Both of their innovation laboratories are focused on entrepreneurship and facilitating deeper learning through hands-on trial and error rather than rote memorization of books or web sites.

The skills we hope students strengthen are collaboration, grit, determination, patience, and persistence; no book or web site or instructor can give someone those skills, but almost anyone can develop them with access to resources and a helping hand. Among friends, the joke is that of course I’d focus on healing fingers in a hands-on laboratory, because my left hand is awkward looking compared to most peoples’s.

I broke my left ring finger just below the middle knuckle in a high school wrestling match two weeks before Big Daddy’s funeral. It healed askew, and to this day it looks like Dr. Spock’s split-finger salute in the Star Trek films and television shows, when he wished people to live long and prosper. On x-rays, you can see the fracture line and calcium buildup that would have been stymied by a small screw or simple pin across the fracture. When I raised investment capital in the early 2000’s – a long and tedious process that required persistence and luck more than talent – I held up my hand and showed its x-ray and said that my finger would have been a candidate for small bone-healing implants.

My left hand’s also scarred from a machete gash along the length of the first finger from when I was ten years old, and a mishmash of barbed wire pinpoints and small slices from when I was 13. Even without the scars, the knobby middle knuckles of both hands stand out, and so does the calcium buildup and callouses around the two first knuckles of each fist, a result of poor choices when practicing Ku-Kempo as a teenager, punching wooden panels with perfect form to develop muscle memory and strengthen the alignment of knuckles, hand metacarpals, wrist carpals, and the radius; doing countless pushups when training to compete against better wrestlers my senior year of high school; and, because I was in the army’s delayed entry program, to prepare for what I thought would be challenging service as a paratrooper in the 82nd Airborne after high school.

Thousands of people have stared at my hands since 1990, maybe more. I’ve been an amateur magician since a kid, and for decades I’ve performed in the downstairs member rooms of Hollywood’s Magic Castle, and in a few San Diego venues near the convention center, like The Gathering Restaurant and Lounge in Mission Hills, a 30 year old venue owned by an aging lifetime member of The International Brotherhood of Magicians. When asked, I sometimes joke and say I broke my finger wrestling Hillary Clinton. That usually gets a chuckle, but it’s true.

In 1990, Hillary Rodham Clinton was the wife of Arkansas governor William “Bill” Clinton, but few people knew their names because President Clinton wouldn’t be elected until 1992. The Hillary Clinton I knew was the three time undefeated Louisiana state wrestling champion at 145 pounds, a fierce beast who would have impressed even Big Daddy. The joke about that Hillary – though never to his face – was that he was like a boy named Sue in Johny Cash’s song “A Boy Named Sue,” who “grew up tough” and “grew up mean” because of his name.

But Hillary wasn’t mean. He was terse and focused and intimidating, but he was never mean. He was the toughest 145 pounder in Louisiana and captain of the revered Capital High School Lions when I was co-captain of the Belaire High Bengals, and any jokes about his name were made respectfully and never within hearing distance.

In hindsight, when I Craig was preparing to portray Big Daddy and he asked what I remembered that could help him bring a bit of authenticity to the role, I wish I had started with wrestling Hillary Clinton. I didn’t have time to think about it then, and it had been almost 35 years since our final match and Big Daddy’s funeral. I showed up at Green Oaks Memorial with my two middle fingers buddy taped and Hillary on my mind, and, for me, the two events are locked together stronger than my fingers were.

Unlike Edward Grady Partin Senior from The International Brotherhood of Teamsters, you’ve probably never heard of the Hillary Clinton from Capital High School. Everything about Big Daddy is online or published in a plethora of books about Hoffa and the Kennedy’s, but to share my memories of him I need to start with Hillary. Like Big Daddy, he mattered then and his legacy matters today.

That’s why I am finally sharing their story.

Go to the Table of Contents

- From “Hoffa: The Real Story,” his second autobiography, published a few months before he vanished in 1975 ↩︎