Wrestling Hillary Clinton: Part I

But then came the killing shot that was to nail me to the cross.

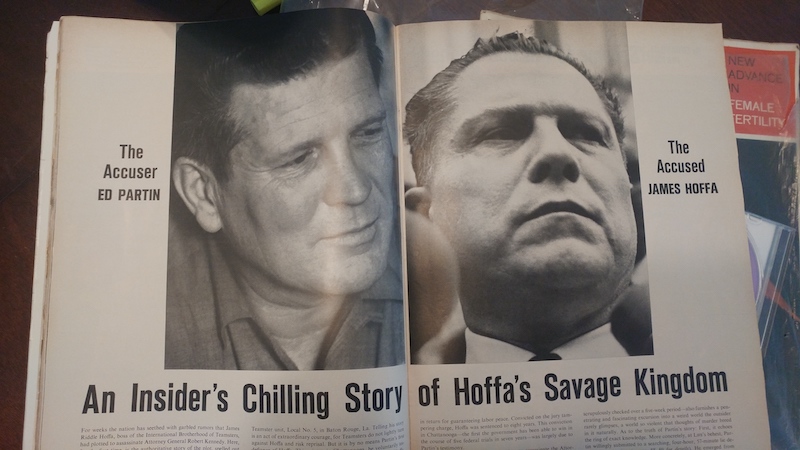

Edward Grady Partin.

And Life magazine once again was Robert Kenedy’s tool. He figured that, at long last, he was going to dust my ass and he wanted to set the public up to see what a great man he was in getting Hoffa.

Life quoted Walter Sheridan, head of the Get-Hoffa Squad, that Partin was virtually the all-American boy even though he had been in jail “because of a minor domestic problem.”

– Jimmy Hoffa in “Hoffa: The Real Story,” 19751

I’m Jason Partin. There are many Jason Partins on the internet; I’m the one listed by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office under both Jason Partin and Jason Ian Partin for inventing implants to accelerate healing in small bones, like in the fingers and wrists or the toes and ankles. I’m also the Jason Partin who is a veteran of the first gulf war and was a part of three congressional inquiries into a chemical weapon exposion after the battle for Khamisiyah airport on 03 March 1991; at that time, I was known as the 18 year old grandson of Edward Grady Partin Senior, the Baton Rouge Teamster leader famous for sending Jimmy Hoffa to prison, whose 1990 funeral was national news and the most talked-about event in Louisiana that year.

For me, 1990 was mostly about wrestling Hillary Clinton and how he broke my left ring finger, just below the middle knuckle, in the Baton Rouge city wrestling tournament finals on 04 March 1990, almost exactly one year before the battle for Khamisiyah; it healed askew, and to this day my left ring and middle fingers are permanently spread apart like the split-finger salute from Star Trek’s Dr. Spock, wishing people to live long and prosper. Today, as a hobby I’m a close-up magician and member of Hollywood’s Magic Castle, where people stare at my left hand all night and many have asked what happened to my finger.

That was two years before President Bill Clinton became president and I first heard the name Hillary Rodham Clinton; the Hillary in this story was the three-time undefeated Louisiana state wrestling champion at 145 pounds, and captain of the revered Capital High School Lions. I wrestled him in the Baton Rouge city finals, and he pinned me in three minutes and forty seconds. At the time, I was 17 years old and about to leave for the army; I wouldn’t hear about Arkansas governor Bill Clinton and his wife, Hillary, until the 1992 presidential election, when I would coincidentally be a paratrooper on President Clinton’s quick-reaction force.

In high school, the joke about Hillary Clinton was that he was like Sue in Johnny Cash’s song, “A Boy Named Sue,” a kid who learned to fight rather than be bullied for having a girl’s name; as Johnny sang, “he grew up tough and he grew up mean.” But no one thought Hillary was mean; he was terse and intense and the best wrestler in the state of Louisiana, but he wasn’t mean, and the jokes about his name were never told to his face.

Hillary was born in March of 1971, and by the end of the 1989-1990 wrestling season he was a legal adult about to turn 19. He had been shaving since at least the 11th grade, which everyone knew because referees checked our faces and forearms for stubble at weigh-in before each match. A few rare wrestlers shaved a few days before a match to make their chins and arms abrasive like sandpaper, but Hillary didn’t cheat. He shaved his face smooth each morning before competing, and his stout hairy forearms were so strong that he could cross-face anyone without needing stubble. If someone grabbed his leg, he cross-faced the hell out of them and they let go. In our first match, he cross-faced me so hard that my nose bled profusely and the referee stopped the match and I lost by forfeit.

USA Wrestling rules added two pounds to each weight class after Christmas to account for growth, and by March of 1990 Hillary was a 147 pound hairy terror. He was only 5’4″, and his extra two pounds went straight to muscle. His burly arms were proportionate, not gangly like a lot of growing teenagers, so his body didn’t waste precious pounds on an otherwise useless extra inch of arms or legs. His thighs bulged with muscles and his lats were wide, so to fit into his elastic wrestling singlet he had to wear a larger size than his lean stomach needed, and the singlet looked like a maroon-colored second skin painted over his dark black body, but with loose folds around his tapered waist.

Like a lot of us, Hillary had to sweat off a few pounds before each match. Capital High was next to the downtown 34 story art deco state capital building, the tallest in America back then, an architectural gem built during the depression by Governor Huey Long, Louisiana’s Kingfish, when labor and materials were cheap; the Kingfish’s photo still hangs at the top of the stairs by the bullet holes that killed him when he was a senator about to become president, and it was the tallest capital building in all of America and the tallest building in Baton Rouge, an obvious landmark almost as popular to visit as LSU’s Death Valley, the Tiger football stadium a few miles downriver and visible from the capital’s observation deck. Practically every kid in Baton Rouge toured the capital in middle school, and we’d see high school wrestlers from the downtown training camp running up and down the steps like Sylvester Stallone in the film Rocky. When I became one of those high schoolers, I saw Hillary wrapped in big black plastic bags, running up and down the steps every Friday before Saturday weigh-ins, sweating off a few extra pounds.

Capital High was – and still is – a mile from the state capital building. It was in what most people called a bad part of town, an overwhelmingly African American community under the I-10 and I-110 interstate overpasses that criss-crossed around our capital building, part of the urban poverty islands created by America’s interstate system in the 1950’s and 60’s at a time when Martin Luther King Junior and other leaders were fighting for African Americans to ride the same buses and attend the same schools as white children. I, like most other white wrestlers, only ventured near Capital because of the downtown all-city wrestling camp, a nonprofit gym founded by former LSU wrestlers and housed in the only building they could afford, an old asbestos-lined garage near the state capital that they padded with faded purple and gold wrestling mats left over from when LSU disbanded their team in 1979, a consequence of Title IX laws to balance the number of males and females in collegiate sports. I never learned his midweek weight, but Hillary was probably around 155 pounds before fasting for a couple of days and sweating off the last pound or two. Once, I saw him running while spitting into an old 16 ounce Gatorade bottle, cutting another pound by not swallowing for hours.

I was the opposite. I was born on 05 October 1972, so I began my senior year as a 16 year old kid. Had I been born a few days later, by Loiusiana law I would have been to young to start kindergarten, so I would have been pushed back and began kindergarten a year later, starting school at five years old instead of four, and my senior year at 17; I would have been 18 for city finals, and much larger and stronger. Instead, I was 5’6″, two inches taller than Hillary, but a lanky mid-pubescent kid with disproportionately long arms, wide hands with long knobby fingers, and scuba fins for feet.

My singlet was skin tight and pulled taunt by my long torso. I was usually smiling, and pale face was dotted red pimples. I had never shaved and there wasn’t a hint of fuzz on my chin, and fewer than a dozen scraggly hairs grew in each arm pit. Unlike Hillary’s leg and forearm hair, which was thick and curly like the Brillo pads my Granny used to clean her cast iron skillet, the hair on my arms and legs was soft like the fur on a puppy. My hair was close-cropped on the sides, almost like in the army, but a bit longer in the back, like a mullet style awkwardly popular in the 80’s; mine was more to hide an 8-inch long scar on the back of my head, a finger-width thick and shaped like a big backwards letter C. My back and shoulders were also dotted with bright red pimples, which only showed when I wore the wrestling singlet for dual meets after school on Wednesdays and for tournaments every weekend from November until March.

Though young, I had strong legs from jogging the state capital steps and hiking the hills of Arkansas with dad most summers, and my cross-face was decent because when I pushed my fist across someone’s face my bulbous thumb knuckle caught and opponents nose and hurt more than forearm sandpaper ever could. I was rarely taken down by a shot; my Achilles Heel was a lack of upper body strength, and I was vulnerable to throws and bear hugs by burly opponents like Hillary.

Hillary’s strength isn’t exaggerated in my mind, and the difference in our maturity made sense after I read a book by Malcomn Gladwell called, Outsiders,” a book about research studies showing why some people excel when others don’t, that begins when researchers learn that professional hockey players in Canada were statistically likely to be born in March, like Hillary Clinton was. Like Hillary, those Canadians started each year of school as the oldest kids in class, when the difference between four and five years old is more than 20% of life along an exponential growth curve grows with each year, especially in a system that categorizes and groups kids according to abilities. Our relative advantage or disadvantage at four to five years old leads to a lifetime of self-fulfilling prophesy few people notice; for professional hockey players, that meant a lifetime of being picked first for teams, training with other advanced athletes, and always floating to the top of whatever pool they join at the beginning of each school year. Malcomn Gladwell dubbed their advantage “The Matthew Effect,” after the New Testament’s Matthew 13:12, where Matthew wrote something like:

Whoever has, will be given more, and they will have an abundance; whoever does not have, even that will be taken from them.

Matthew 13:12 is harsh in context of kids competing and social equity, but I was lucky. If I had anything in abundance, it was what my teammates called tenacity, a trait demonstrated by getting back on the mat against Hillary no matter how badly he beat me. I inherited tenacity – but not large size and natural strength – from my biologic father, a burly street brawler and drug dealer, who inherited it from his father, a former heavyweight boxer with a criminal record you could write a book about.

Because of a quirk in the law, I was also a legal adult in 1989. A week after my great-uncle Bob’s funeral on 03 August 1989, the coincidentally named Judge Robert “Bob” Downing of the East Baton Rouge Parish 19th Judicial District granted my request to be emancipated from my family. The justice system of Louisiana based on the Napoleonic Code from when Louisiana, named after King Louis and Queen Anna of France, was a French colony. The code persisted after the Louisiana purchase and then the civil war, stubbornly clinging to law books and making Louisiana have a judicial system unique among all United States, just like it is still divided into Catholic parishes rather than counties like in every other state. Under Louisiana’s code, Judges have more leeway and rely less on predicate cases from the U.S. Supreme Court, so Judge Bob could practically do what he wanted. He told me what I had to do, and I began the paperwork as Uncle Bob lay dying.

According to Louisiana law, I had to sign a document saying I “prayed” for emancipation from my family. I’ve never been religious and I try not to lie, but I signed the paperwork and paid the $120 fee using cash from performing three kids birthday parties for $40 each. My dad was in prison again and unavailable for comment, but Judge Bob couldn’t interviewed my mom and he answered my prayer by stamping the raised seal of Louisiana – a Pelican nesting her babies above the words “Union Justice Confidence” – on an emancipation decree slightly larger than a sheet of legal paper. After Uncle Bob’s funeral, I brought the decree to an army recruiter’s office and joined the army’s delayed entry program, signing a contract to leave for basic training 11 months later and beginning service as an E2, not an E1, and therefore earning an extra $75 a month, which was more than I earned hustling magic shows every summer.

I was guaranteed $36,000 for college from the GI Bill, infantry school, and an assignment with the famous 82nd Airborne Division if I passed Airborne school. The contract depended on me graduating high school, passing the ASVAB test, and not being found guilty of a crime. If I were arrested, Judge Bob had emphasized, I’d be charged as an adult and go to jail, just like my dad and his father, and not even he could help me. I said I understood; and, though I had practically failed out of high school my first two years, I brought in my report card to show I was doing better now that I wrestled, and I said that I would work extra hard to ensure I was ready for the army and 82nd Airborne.

I was average in academics and strength for a 17 year old, but I was persistent and would show up to practice early and stay late, teaching basic wrestling moves to 250 pound football linebackers nearly as strong as Hillary so that I could practice my defense. I weighed around 152 midweek, and I fasted one to two days before weigh-in. Lea sometimes drove me to the downtown wrestling club and I joined other wrestlers tackling the state capital steps sweating off a few pounds and building leg strength; Baton Rouge is a flat city barely above sea level, and the capital building was the only place we could run uphill unless we did laps on football bleachers, which became boring after an hour or so. Sitting in class on Fridays, I ducked my head down and subtly spit into a Gatorade bottle I held between my legs. I began every morning around 4am, studying algebra and physics for an hour then doing around a hundred pushups and running four to five miles, spitting into the grass along sidewalks of the streets around Belaire High School.

When Coach noticed me training extra hard, he showed me how to be more efficient by using my gangly arms and legs as fulcrums with the cradle, wrapping my long arms around an opponents neck and a leg, locking my hands, and bringing their knee to their face and rolling their shoulders to the mat. I learned that I could pin even the linebackers once I clasped my hands. Thanks to Coach, I grew to have the strongest cradle in all of Baton Rouge, maybe even in all of southern Louisiana.

The trick was to not clasp both hands together like a handshake, but to lock them with thumbs flat against the first fingers (Coach said: “A wrestler looses 15% of his grip strength if his thumb is out”). And, instead of squeezing harder and straining against a stronger opponent (“An opponent’s legs are stronger than your arms”), Coach showed me how to bring my elbows together by focusing on moving my hands away and using my long arms as fulcrums, like how pivot points of a bolt-cutter amplifies your strength and cuts through steel. I began pinning teammates the same day he showed me that trick, and I didn’t stop all year.

To get even stronger, I took Coach’s advice and began crumpling the Baton Rouge Advocate one page at a time, forming tight balls and dropping them on the floor until there was a hill of paper balls and my forearms were screaming for me to stop. I used my duct-taped handgrips in school, oiling the springs so I could exercise under the table without teacher’s hearing squeaks, and when I wasn’t in school I crumpled every newspaper I could find, leaving my blue Belaire hoodie stained with black fingerprints. The bulky Sunday edition was dedicated to the end of tournaments, when I’d have a few days to recover before Wednesday’s dual meet. I’d save the comics for last and read them above a pile of crumbled paper balls in Coach’s floorboard.

When Uncle Bob was sick and I couldn’t train at the downtown camp, staying with him in the hospital and then at his home in lieu of the more expensive Hospice care, Coach picked me up once a week so I could practice in New Orleans with the top-ranked school in Louisiana, the Jesuit High BlueJays. I rode in the passenger seat of Coach’s old brown Ford F150 full of mops, five-gallon buckets of inexpensive fungicide, and extra wrestling headgear along the serpentine River Road between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, dropping off gear at Region I schools even smaller than Belaire; Coach was like the Santa Claus of Louisiana Wrestling. Just before Jesuit, we’d stop at St. Paul’s Middle School in Covington, where Coach would say hello to his son, Craig, St. Paul’s wrestling coach. They’d hug and laugh and talk about how to get more school programs started, especially in the predominately Cajun schools closer to Lafayette, where French settlers landed 300 years before and whose economy centered around agriculture and offshore oil drilling, and where all the schools were small public schools funded almost entirely by local taxes, which were meager in rural Louisiana. Like most schools in Louisiana, football dominated high school sports, and the biggest students dominated football; what Coach offered was a sport that suited every size and stature, and allowed individuals to thrive in a system that hadn’t changed in hundreds of years.

When we reached Jesuit High School, Coach would chat with Coach Sam, a diminutive Japanese champion of both wrestling and judo, about what Coach called, “This, that, and the other thing…” and I’d train for an hour with their second or third string team while the first-string was off winning national freestyle tournaments. I’d end up sweaty and with scrapes on my cheeks from Jesuit guys dragging my face across the mat, staring at their wrestling-dedicated gymnasium with two mats and rafters adorned with state titles dating back to what seemed like when Cajuns first arrived in Louisiana. Their mats smelled like the fancy fungicide that didn’t burn your cheeks and that no Baton Rouge or River Road school could afford, and all had parents in the parking lot waiting for them to finish Saturday morning practices.

On the ride back to Baton Rouge, I’d work on my cradle-locking hand strength. The drive was about an hour and a half, enough for at least one Advocate newspaper to be transformed into a pile of compacted paper balls the size of golf balls. At least once every week or two, I’d see a photo of my grandfather, and on those days I crumpled the balls even tighter. He had been on the front page of the Louisiana newspapers since I was a little kid. By March of 1990, my name was showing up in the sports section almost as often as my grandfather’s name in the politics section; I was consistently winning third or fourth place in tournaments, enough to warrant my name listed in the big tournaments where third or fourth place was respectable; I joked that it was the first time a Partin made the news for something respectable, and I grew to be proud of seeing my name and Belaire High School listed beside wrestlers from schools like Jesuit.

My teammates quipped that I had a kung-fu grip and was stronger than I looked, and they began to believe that I could actually beat Hillary. They rallied to help. They took charge despite me being co-captain, and forced a modified version of King of the Mat by insisting I remain on the mat even if I were taken down. I’d face a fresh wrestler again and again and again. After an hour of that, I was so weak that even Little 103 pound Paige could topple me.

No matter who took me down, I’d raise one knee and put both hands on it and force myself back up to face each fresh wrestler. The game would continue until Coach made us quit so he could turn off the lights and go home to Mrs. K. I was in remarkable physical condition. I had a kung-fu grip and the focus of a sniper’s scope; a few months later, I’d consider basic training, advanced infantry school, and Airborne school trivial by comparison, a sentiment shared by other wrestlers I’d meet in service over the next seven years.

Armed with physics and with Coach in my corner, I clawed my way from loosing all 13 matches my sophomore year to finishing my junior year 76-35. By the city tournament my senior year, I had an impressive record of 56-12 and was ranked third; though I had never competed in finals except for smaller tournaments like Coach’s Thanksgiving and Christmas tournaments, when many wrestlers took a break from fasting to be with families. Hillary had been captain for almost three years, and his senior record before City was 45-0. For the first time in my high school career, my name wouldn’t be limited to the loser’s bracket for third and fourth place, because I had made it to finals and was a guaranteed silver medal; I had a chance for the gold, and with all of my teammates believing in me I began to suspect that I had a chance at beating Hillary Clinton. By then I had 36 pins, most with the cradle.

I don’t know what Hillary thought of my cradle, because we had never spoken. As co-captain, I stood beside Jeremy Gann, the other Bengals co-captain, and we faced Hillary before every pre-tournament meeting and dual meet, shaking hands in front of spectators to represent the fair play each of our teams promised, but we didn’t chat. We drew attention because it was always Jeremy and me against Hillary; Belaire had the only co-captains in the state of Louisiana, maybe even the country. That was because Coach had teams vote for their captain using his version of the Most Valuable Player or Coach’s Award, a ranking system of the top five choices that facilitates competing teams to agree upon a winner, similar to how ranked-voting is discussed as an alternative to voting for only one candidate in American democracy. (The only reason we had co-captains was that Jeremy voted only for himself, and I ranked Jeremy first and listed four other wrestlers but not myself.) It’s possible that we either intimidated or confused captains every time we stepped on the mat as co-captains, which is why not many people asked us about it.

But I can’t imagine Hillary being intimidated by anything, and never spoke away from the mat, either. We saw each other at the state capital steps when we ran with other equally terse wrestlers, and I never saw him at the downtown all-city training camp. Despite Capital High being jogging distance to the downtown wrestling camp, the Lions kept to themselves and didn’t train with the mostly caucasian all-city team, with only Baton Rouge High’s Clodi and Chris standing out among us.

In hindsight, it’s easy to see why Capital never joined us, just like it’s easy to see how Hillary had such a physical advantage over me. The capital is surrounded by civil war barracks and the original LSU campus, called “Old War School,” which supported the surrounding plantation homes by training military leaders to preserve slavery. Governor Huey “Kingfish” Long built the state capital and then drained the nearby swamps to build today’s LSU, keeping the original LSU as a museum to The Old War School, showcasing where southern gentlemen trained as officers in the confederate army. In the state capital lobby a plexiglass display protects bullet holes from when The Kingfish, by then known as presidential candidate and U.S. Senator Long, was assassinated by his bodyguard, a tribute every middle school kid who takes a field trip sees and hears about; surrounding the capital grounds are buildings pot-marked with bullet holes from what one of my teachers once quipped as “The War of Northern Aggression,” though no plexiglas protects them and there’s no sign telling you why they were there. From the crow’s nest atop the capital, we stand atop the tallest skyscraper we could imagine and peer upriver towards Saint Francisville and see Fort Pickens, site of the longest battle of the civil war, where Baton Rouge soldiers trained by officers at the original LSU fought 378 days to preserve their way of life. It’s no wonder Hillary looked so intense when he ran up and down the state capitals 34 flights of stairs again and again, and why The Matthew Effect applies not just to kids in school, but to neighborhoods and generations of families born into relative advantage or disadvantage.

I had wrestled at Capital High School twice for dual meets, once in 1989 and once in 1988. They called their gym the Lion’s Den, an intimidating name to match their reputation as rough kids in a bad neighborhood. They intimidated visiting teams with their black skin hidden under the dark hoodies, especially when they trotted onto the mat to warm up. They formed a disciplined line and stomped their left feet on every other step as they trotted in a straight line behind Hillary, lined up 103 pounds to the 275 pound heavyweight like a row of black and maroon Russian Matryoska dolls marching to a James Brown funk beat on the 1 of a 4 bar count: One! two-three-four, One! two-three-four, One! two-three-four as they circled the mat a few times and gradually increased their speed, stopping to drop and do sprawl drills and then clustering together as if to form a single maroon entity in the center. They did the same routine when visiting other schools, but it never had the same impact as in the Lion’s Den, a dilapidated and asbestos padded room with peeling maroon paint faded and duct-taped mats that were so dusty faded few people noticed they were purple, not maroon, and had been donated by Coach and the other LSU wrestlers around the same time they founded the downtown wrestling camp. The Lion’s Den was an obvious reference to the Old Testament and Daniel being tossed into the lion’s den to test his faith, and we quipped that it took more than faith to leave Capital’s gym alive.

Their gym’s doors were adorned with crudely painted but obviously adored murals of a gold Lion of Judah in the red, yellow, and green colors of the Zulu parade in New Orleans, and the dark maroon hoodies stood out in the Lion’s Den more than in any other gym. But for me, the most remarkable part was seeing all of those wrestlers follow Hillary silently and reverently no matter where they warmed up. I wondered what he did to inspire such devoutness, and how he improved when he was the most formidable wrestler on their team. I got better by being beaten by Hillary and by focusing on him, but I never learned what drove him to become state champion every year since 1987; he was an introvert, like I was, and I assumed he got more motivation from his life experiences than from the banners that adorned schools with more wealth, like Jesuit.

The Lion’s Den bleachers were always filled with parents and neighbors who could walk there, and who stomped their feet to the rhythmic beat of Hillary and the Lions jogging in a circle on the mat to warm up. In both dual meets, the bleachers were filled with African American families who could walk to the Lion’s Den, but I can’t recall a single caucasian face nor do I remember any Belaire parents driving all the way downtown after school on a Wednesday to watch us compete; I never learned if other schools drove to the rough neighborhood of Capital to watch dual meets, though I would see some of Capital’s parents at weekend tournaments, wearing maroon shirts and sporting headgear the colors of Zulu’s parade. Capital had several state champions, individuals rising above circumstance in a way unique to the sport of wrestling compared to all team sports.

Baton Rouge High hosted City in 1990; it was a public school, but the most prestigious in Baton Rouge and a magnet program that creamed the highest academic students and was somehow funded with new, bright green uniforms and wrestling mats. Probably because the city tournament was at Baton Rouge High, the bleachers were packed with almost two thousand people watching matches on four mats, including the twenty or thirty fans of Capital who sat together near Hillary and the Lions.

I won my first three matches, two on Saturday and one on Sunday, upsetting the number two seed in semifinals, Frank Jackson, a formidable opponent from Brusly High that I had faced a few times in 1989-1990 season. Frank and I went into city tied 3:3 overall, and I defeated him that day by holding him in my cradle for almost a full minute in the final round; the buzzer sounded and I won 3-2, bringing our lifetime record to 4:3 in my favor; it was the last time we’d compete against each other. We shook hands and the referee raised mine, and we joked that the punishment for winning our match was facing Hillary Clinton; that was the last time we’d speak. I walked to Belaire’s corner and accepted a towel from Jeremy; Coach shook my hand and looked up and said, “Good job, Magik.” The gym cleared after semifinals, and Baton Rouge High Bulldogs rearranged the mats to have just one in the center.

People paid $2 to come back inside and see final, and bought food from a small concession stand to raise money for things like free fungicide and ear guards. Coach’s daughter, Penny, worked the concession stand when she wasn’t taking classes at LSU, and sometimes Mrs. K was there to support us. I, like a lot of wrestlers around Penny, smiled and stuck out my chest and squared my shoulders when I ordered a $2 slice of pizza (though she often gave me one for free). She’d seen my match against Frank and had a few tips to offer. Penny was a freshman at LSU who grew up in Iowa with a household of wrestlers, and she often offered tips or told stories of her two brothers cutting weight every year. Her brother, Craig, moved to Baton Rouge when the Ketelsens did and was Belaire’s only wrestler in the early 80’s and our first state champion and became a respected Coach in New Orleans, so I relished in her advice and lingered over my slice of pizza. I did fine, according to Penny, though I seemed reserved compared to how I wrestled in practice.

Stage fright, I quipped, which wasn’t true. I was more comfortable in competition than in any other aspect of my life. Penny was right, I took more risks in practice than in competition and my scores against serious competitors were always low and close together, uneventfully leading to wins with scores like 3-2 or 5-4. I don’t know why I did that, but it was so different than how Coach or Craig wrestled that of course Penny would comment. But even she forgot that, unlike Craig, who had wrestled all of his life, I was only a second-year wrestler and I was doing better than any of the sophmores or juniors who, because of the quirk about my birthdate, were the same age as I was. All of the Bengals were doing well, though we couldn’t be generalized like the Lions or the Bulldogs. We lacked the formality of Lion’s warm-up routine or the crisp matching uniforms of the Bulldogs; we were an obvious collection of teammates who each did things their own way. That was another affect of Coach, a diminutive man who knew what worked for a 126 pounder may not work for a 160 pounder or heavyweight, so we were given freedom to find our own way. My way was conservative in competition, aggressive in practice. A few months later, instructors in the army’s advanced infantry school would point to a hand-scribbled sign over our training field that spoke how I felt about practice: More sweat in training means less blood in combat. Coach never pressured me to be anything different than I was. Neither did Penny, she simply commented on what she saw and she was right; I wondered if I’d wrestle differently if I had come from a family like hers and had the confidence of years of training but with nothing to prove.

Recharged after chatting with Penny and eating for the first time in two days, I walked away from the concession stand, watched finals for the lower weight classes, and began preparing to wrestling Hillary Clinton for the seventh time.

He had one all six matches against me that season and once two years before, in my first match against him. We showed up for a scrimage at Capital High and I shot first, like I would in practice against teammates, but Hillary wasn’t my teammate and he cross-faced me so hard my nose burst and he pinned me while I choked on blood; that was in 1987, before the Reagan administration admitted AIDES existed and was contagious to even heterosexual people, and wrestling rules didn’t stop matches at the sight of blood yet. He quickly pinned me that match, and he pinned me three times in 1989; by that time the rules had changed and matches would stop for blood, but I so rarely shot that he didn’t get a chance to cross-face me again and I stayed on the mat longer and longer each time, and grew stronger and more talented with every loss, and I accelerated in skills and focus after the Christmas and New Years break of 1989-1990.

It was over Christmas of 1989 that the 82nd Airborne parachuted into Panama and overtook the country within a few hours. For thirty days, daily news showed the paratroopers surrounding President Noriega’s compound with machine guns and huge speakers, blaring heavy metal music into the compound 24 hours a day to get Noriega to surrender. Several Navy SEALS and Army Delta-Force commandoes died, and the world watched interviews with paratroopers not much older than I was. I jumped rope and watched the news and saw myself in the future, and to help myself then I began training harder than I imagined Airborne or SEALS or Delta Force training; I began to see each time on the mat like combat, real and important and a test of everything we had done or not done to prepare for that moment; every unfocused moment increased the chances I’d die like the SEALS or Delta Force commandoes who were much older and stronger than I was at 17. While the 82nd was on the news, I began focuses every waking minute on the tangible goal of defeating Hillary Clinton rather than the nebulous idea of possible future wars I’d fight. I’ve never been a person who remembers my dreams, but I woke up being a bit more confident in every move, as if I wrestled in matches all night long. After the 82nd returned to Fort Bragg in January of 1990, I silently vowed I’d let me neck snap before I was ever pinned again, and no one, not even Hillary, had pinned me in the months leading up to city finals six weeks later. Other coaches noticed and they bumped my seating up to third, which kept me out of Hillary’s bracket for the first few rounds and paired me against Frank in semifinals, saving what coaches planned would be the most exciting match for finals when only one mat was on the floor and everyone was watching.

When Clodi began to warm up so did I; he was 136 pounds, but seeded first and likely to pin his opponent quickly, and then it would be Belaire’s other co-captain, Jeremy, was also seeded first. But Jeremy had faced the second seed a few times and they were closely enough matched that he could be pinned, and I knew that his and Clodi’s match could be over within a few minutes. I wanted to ensure I was warmed up, just in case. I skipped rope while listening to a mixtape that included songs from the 1985 Vision Quest soundtrack. I used an old Sony Walkman despite having a CD player by then, a Toshiba player and the nicest available in Baton Rouge’s shopping mall, given to me by Uncle Bob before he passed; it was his final gift to support me when spine cancer kept him bedridden, a way to be in spirit after he was gone, but back then there weren’t CD burners to make custom playlists like we could with dual-cassette boom-boxes, and even the best CD players skipped when I jumped rope, so for tournaments I still listened to my Walkman.

I had been using the same mixtape for a year. It had songs like “Lunatic Fringe” by Red Rider and “Hungry for Heaven” by Rio, both from Vision Quest, and “Jump!” and “Panama” from Van Halen’s 1985 album aptly titled “1985.” Van Halen was probably the most popular hard rock band back then, especially before their split with David Lee Roth. I knew all the lyrics by heart, and as I watched the mat my mind sang along in a ritual I repeated around 50 to 60 times a year. Ironically, Panama spoke about not having discipline:

Jump back, what’s that sound?

Here she comes, full blast and top down

Hot shoe, burning down the avenue

Model citizen, zero discipline

The repeated chorus is what most people remember, and it’s what the news played every time they showed the 82nd with machine guns and towering speakers pointed towards Noriega’s compound:

Panama

Panama

Panama

Panama, oh-oh-oh-oh

Panama

Panama, oh-oh-oh-oh

Panama

After a week of hearing Van Halen 24 hours a day, President Noriega was probably the only person on Earth other than David Lee Roth who knew the lyrics to Panama better than I did. I listened to it before every dual meet and before every match at tournaments up until city, skipping rope and working up a sweat.

The tape alternated songs to shuffle how I skipped rope. Belaire’s heavyweight, a cheerful beat-boxer who mimicked Chuck D fromn Public Enemy and all three of the The Fat Boys, pointed out that in Rocky V Sylvester Stallone developed rhythm to fight the big Russian by listening to his African American peers, so Big D added a few of electronic jams to my playlist and got me to dance to them while I skipped rope. The most memorable song was “Don’t Stop the Rock” by Freestyle; every time the chorus came up, I sped up my pace and criss-crossed my hands and bounced on one foot at a time to the beat:

Freestyle’s kickin’ in the house tonight

Move your body from left to right

To all you freaks don’t stop the rock

That’s freestyle speakin’ and you know I’m right.

da, da, da-tada-da-ta

da, da, da-tada-da-ta

da, da… tada-da-ta

I skipped and breathed slowly and coaxed out a thin sheen of sweat, transitioning my body to burning the tiny bits of fat that tenaciously clung to my body no matter how much I trained or cut weight; if I had a physical advantage over anyone, even Hillary, it was that I seemed to maintain strength in later rounds, probably because I tried to slow-burn fat rather than stronger but shorter lived muscle glycogen. I had learned that from one of Coach’s Olypian-training folders, and though it wasn’t his style he encouraged me to lean into my strengths. I ran cross-country before wrestling season and jumped rope in my free time, and it seemed to work for me. I kept one eye on the mat to ensure I didn’t miss my match, a risk to anyone wearing headphones who likes to warm up alone. A few teammates kept an eye on me, just in case. We scored as a team based on each individual’s performance, and though we were ostensibly less disciplined than other teams, we were never out of each other’s sites, especially because a forfeited match cost the team a lost opportunity.

Clodi won by pin in the first round, then Jeremy won by points after all three rounds. We were happy for that – a gold medal increased the team score, and Belaire’s fledgling team was doing well enough to place in the top four that year. Jeremy had dropped down from 145 at the beginning of the season, unable to even score on Hillary, and I dropped down from 152 to fill the empty spot; we had several 152 pounders, and though I began the season at 145 just for the team score, I had grown to focus on trying my best to beat Hillary, just like that kid in Vision Quest had focused on dropping weight to wrestle Shoot, the three time undefeated state champion in the film. After seven losses, City could be my turn to win; I had done all I could to train, and now it was time to step onto the mat. I pushed the stop button on the Walkman, jogged to the chair beside Coach, took off my hoodie, and handed the Walkman and jump rope to Little Paige. Jeremy took his seat next to Coach. A handful of Bengals in blue hoodies gathered by the bleachers about ten feet behind them. I put on my headgear and trotted to the center of the mat, shaking my arms and moving my legs.

The referee stood beside us as we put our lead feet on the line and faced off. He asked us to slap hands, a handshake of sorts to encourage fair play. He stood back with his whistle in his mouth and his hand raised, and suddenly dropped his hand and blew his whistle, and both of us were in motion before the sound waves reached spectators in the upper bleachers, and a fraction of a second later Hillary and I collided so hard the gym rafters rattled as if a truckload of C4 explosives detonated in the center of the gym.

A minute and a half after our clash we were drenched in sweat. He was up 2-1 after having taken me down with a low single; I escaped by standing up so hard I shot for the moon, burning most of my muscle glycogen but freeing myself to keep fighting. Hillary and I faced each other and circled slowly. My heartbeat was racing and my breath was deep and faster than I could sustain, but Hillary seemed the same. We were near the center, an arm’s reach apart, and he tapped my head to temporarily block my view and allow him to shoot another low single.

But I was watching his hips and was therefore undistracted by his tap, and I sprawled and cross-faced him and spun behind; instantly and automatically, my right arm shot around his neck and my left arm slid under his leg, and I clasped my hands and had a cradle on Hillary for the first time: I felt rather than thought that I could win. I only had a moment to savor the feeling, because his muscular leg began kicking against my hands with the cadence and urgency of 1-2-3 chest compressions on a dying teammate in the midst of battle, but with the force of a .50 caliber machine gun firing relentlessly at charging tanks and rattling our heavily loaded humvee with every burst of fire. He kicked like the man Sue fought in Johny Cash’s song, the one who “kicked like a mule and bit like a crocodile.”

Hillary didn’t bite like a crocodile, but his kicks were so fierce and relentless that they ripped my focus away from victory and towards clinging on to the cradle so he wouldn’t get escape points. My sweaty hands began to slip apart. Soon my right hand was clasped only my left ring and pinky finger. He kicked again, and my left thumb slid too far away from my grip to do any good. I clamped on with my kung-fu grip with everything I had in me; when I saw the 82nd and vowed to never quit, it wasn’t just about being pinned, it was about not quitting my grip or my focus, no matter what I was doing, and I wanted to hold Hillary down and prevent him from scoring escape points, and to maybe earn back points if I could hold him still for three seconds. Hillary knew situation, and he was probably more focused than I was; he kicked with bone-rattling strength again and again, grunting as loud as a shotgun blast with every push.

I felt my finger snap and my grip shift. It hurt like hell, but I was too focused to pay attention to anything but not quitting. I clung on with my right hand with all the tenacity I could muster, but he kicked again and Hillary broke free and stood up and turned to face me with the speed I had grown to respect. We were face to face again, his strongest position, and his bushy eyebrows furrowed with anger. I had never seen him angry on the mat before, and I only had the smallest fraction of a second to realize that before the buzzer sounded. The referee awarded him an escape point, and me a takedown without back points: we were tied 3-3. The ref pointed us to our corners.

I had lost a chance: people make mistakes when they’re angry. Some Greek poet had said that when the gods want to torture someone, they first make them angry, and almost every coming of age film in the 1980’s showed heroes trying to temper themselves; Mr. Miagi had taught the Karate Kid patience, Yoda had warned Luke that anger leads to the dark side of the force, and the only match the wrestler from Vision Quest lost was one where he got mad about his nose bleeding. The only one who benefitted from being angry was television’s Bruce Banner, who turned into the Incredible Hulk when he was angry, but even an angry Incredible Hulk would have been humbled by a focused Hillary Clinton. I wanted a few more seconds before Hillary could calm back down.

Jeremy was beside Coach and ready with a fresh hand towel that smelled of fungicide, like everything carried in the back of Coach’s truck. I wiped the sweat from my eyes, only to have more pour down my forehead, pool in my eyes, and drip off my nose and chin and splash on the mat by my shoes. I alternated between shaking my limbs to stay limber and dabbing sweat off my face, mindful of the break on my ring finger, swollen to a useless rigid plank. Coach asked, and I said I was fine. He nodded, briefly showing the bald spot poking through his whispy grey hair on his flat, acorn-shaped head, and stepped back beside Jeremy. I kept my focus on Hillary; I wanted to face him while he was still riled and I was calm.

My breath whooshed in and out through pursed lips while I stared at Capital’s corner, hoping for a glimpse of the strategy he’d apply in our next round. Two of the maroon hooded Lions dried each of Hillary’s arms while he bounced and shook his limbs like a mirror image of me. I stood on the Bulldogs new, bright green mat and ignored the maroon-hooded Lions circling Hillary as if to shield their captain from distractions. I focused on their coach, a spherical mountain of an African American man who couldn’t squeeze into even the largest of sweatsuits. I tried to decipher his hand gestures, hoping for a hint of help against Hillary. The Mountain kept lowering his hand, as if telling Hillary to calm down and focus; in hindsight, he was probably telling him to not shoot on me again, to focus on his strengths and my weaknesses.

The Mountain had never wrestled and the Lions never participated in all-city practices, so many of their signs were different than any other school I knew. Hillary nodded after every one of The Mountain’s gestures. Coach and Jeremy let me be. My cradle was useless, but there was nothing I could do about it. All that mattered was that my breath stabilized and my heartbeat calmed down. I bounced and shook my arms gently to keep them warm and to maintain a sheen of slippery sweat on my legs, a tiny advantage that no one would consider cheating. Hillary’s face was calm, and he shook his feet as his teammates wiped his arms but not his legs; it would be harder to grasp his legs this round, but that was true for both of us and didn’t really change how we wrestled.

The referee called to us a few brief seconds later, and I trotted back to the center of the mat. Hillary won the coin toss, and he gave two thumbs up to indicate he wanted us both standing in neutral position. We put one foot forward and faced off. The referee stood poised, whistle in mouth, and raised his hand. I focused on Hillary’s hips.

Coach only gave a handful of nuggets of wrestling advice in the three years I had known him. One was to watch an opponents hips, not their eyes or hands, because where their hips went, they went. You can fake hand motion to get someone to react, and you can misdirect them with where you stare, but your hips belie where you will go. That was advice from an Iowa coach when Coach was an alternate on the olympic team, at a time when Russians dominated international wrestling because they focused on taking an opponent off their feet, setting up throws with taps to the head that provided just enough distraction for them to penetrate your defenses and get close enough to pick you up. Coach told the same story once a year, at the beginning of practice, practically without change.

“But to do that,” he explained slowly, getting eye contact with each of us before continuing, “they need to get their hips close to yours. Get you to overreach, so they can step in close.”

He paused to let that sink in, then raised a stubby finger and said, “The Russians realized that if you break a man’s stance, you can do what you want to him.” He put down his finger, and said: “Don’t break your stance.”

“Here!” he said, jumping into a gravediggers stance.

“It’s like shoveling dirt all day. Or pig slop,” he said.

One wrestler a time, he patiently caught eye contact with each of us before moving again.

“Here!” he said when we were all looking, and he sprawled onto the mat and landing face down but still in that gravedigger stance, one leg closer to his hips than the other, foreshadowing what he’d look like standing. He pushed with his stubby arms and effortlessly popped back up in that same stance.

“Here!” he said again and dropped back down. He asked a few football linebackers watching from the adjacent weight room to pile on, and he popped up again, just as effortlessly. Lea said it was like little wrinkled Yoda lifting an X-Wing from the Degobah Swamp, and that I looked as dumbfounded as Luke.

“Vince Lambarti said that fatigue will make a coward out of anyone,” Coach would remind us two or three times a year, saying that we could run track or swim before wrestling season and use the football team’s weight room when they were done.

It was easy to understand focusing on hips and training in other sports, but Coach’s most persistent piece of advice, repeated before practically every dual meet and tournament, was the real secret and what separates average athletes from champions. His advice boiled down to two simple words: “Just wrestle.” No matter what happened the previous round or that morning or the weekend before, just wrestle. With everything you have left in you, just wrestle.

I once asked Coach to elaborate, and all he said was that his words had roots from the most celebrated wrestler of a generation, Doug Blubaugh, a gold-medal winner in the 1960 Rome olympics who pinned all four opponents in record time. In trials, Doug had barely defeated Coach, winning 4:3 and only in sudden-death overtime, back when matches were a staggering nine minutes instead of the measly six of my generation. Coach lost and dropped to the third place bracket, held only minutes after his loss in semifinals, knowing that if he won he would only be an alternate in Rome in case Doug got sick or injured. Coach sat, fatigued and distracted by his loss, and Doug walked over to him and said: “Someone will win. It might as well be you.”

Just wrestle.

On the mat against Hillary, I forgot about my finger and focused on his hips and prepared to wrestle. Someone will win. For the next two minutes, it doesn’t mater who, just wrestle.

In my periphery, I was aware of the referee’s chest and cheeks; sometimes, they telegraph blowing the whistle and you may gain a fraction of a second of advantage. I saw the referee blow his whistle and drop his hand, and I began wrestling before the sound wave reached the bleachers.

But Hillary was faster, and he shot a high double that caught both my legs. I sprawled, kicking both feet into the air like a bucking bronco and slamming my chest onto his broad hairy shoulders. He resisted my weight like Atlas shouldering the world and tried to pull my legs closer to him, to get his base under mine. But my lanky legs began to give me a mechanical advantage, and sprawl by sprawl Atlas faltered. Hillary’s arms crept further from his body and his head began to bow, and that’s when I cross-faced him with the force of God.

His head turned and he released his grip. My right hand continued moving into a cradle, my body acting from a core with no concept of pain in my finger. I began to spin behind, my gimpy left hand targeting his raised left leg, but he sprung backwards and towards the mat’s edge, and he popped back into a perfect stance.

We kept eye contact and crab-walked back towards the center, a truce-of-sorts wrestlers fall into without discussing it, ensuring we stay away from the edge of the mat and the hardwood floor and bleachers. We were almost to the center when Hillary’s forearm shot to my neck like a praying mantis snags its prey. He yanked my head forward, tempting me to plant all weight on my leading foot.

Hillary had a lethal head-heal pick, but Coach had told us how to stop it.

“Don’t be a headhunter,” he said.

He was given that advice from the US Olympic coach, because the Russians used the same head-heel setup as Capital High. Don’t react mindlessly, like a brute, and grab their head like they want you to: keep your stance, remain calm, and be alert. The 1960 Olympics were at the height of the Cold War, and the Soviets were already sneaking nuclear missies into Cuba for what would almost cause WWIII in 1961’s Cuban Missile Crisis, so the world was watching the Soviets versus Coach and the U.S. team that year, seeing how they’d react; they didn’t, and that’s why everyone came home alive and with new colleagues in the Soviet Union, bonded by a love of something greater than politics.

“To grab your head,” Coach had said, “They must overreach their stance first.” He paused and raised his stubby forefinger and got eye contact with each of us one at a time before continuing: “Keep your stance. Stay calm. Be alert. Wrestle.”

Hillary’s muscular arm tapped my head forward, but instead of planting my foot to resist I went along with the momentum; my hips dropped below his center of gravity, and I swung my left leg beside his right, and flowed into a high-single that took him to the mat faster than thoughts could materialize. But Hillary’s legendary speed was faster than you could imagine; he sprung back up and faced me so quickly that no points were scored either way. We stood face to face again for the briefest of moments, then he moved so quickly that I don’t recall how I ended up in a bear-hug; I probably blinked.

Hillary’s bear hug caught me on exhale, when my lungs almost empty, and he instantly threw me in a perfect throw that would have earned five full points in summer freestyle, where Hillary beat even the Jesuit varsity wrestler year after year. A five point throw is the holy grail, a perfect 360 degree arc with the opponents feet off the mat, and I was trapped in mid-air, off my stance, weakened like Antaeus lifted from Mother Earth by Hercules.

Those Russians were right: I was in Hillary’s control, and there was nothing I could do about it until I was on the ground again. The ceiling appeared in my view, and above the bleachers I could see the giant Baton Rouge High scoreboard, a late 1970’s giant neon monster with dozens of small orange lightbulbs that spelled out our names and the schools we represented, and with a massive countdown timer so that people as far away as Texas could see how many seconds were left in each round. I watched my size 12 Asics Tiger wrestling shoes, old and frayed and worn into a dull and dusty grey color, that once belonged to Craig when he was a 171 pounder and Belaire’s first state champion, lent to me by Coach when my already disproportionately large feet grew a bit more over Christmas. I watched those shoes fly through the air above my head and in slow motion and creep past the orange neon lights. Hillary and my names and the names of the schools we represented came into view again. They slowly arced back down, inertia keeping them a bit behind my shoulders and hips. I saw faces of fans staring wide-eyed in awe: it was a beautiful throw. Some people, probably those experienced with wrestling, cringed empathetically, because they knew I was about to hit the mat like a meteor crashing into Earth.

Hillary slammed my shoulders to the mat with a thud that shook the bleachers as if a C-130 Hercules had dropped a 15,000 pound bomb in the gymnasium. Yes, that’s exactly what it felt like. Almost exactly a year later, on 04 March 1991, I would watch two C-130’s drop the Volkswagen-sized bombs onto Khamisiya Airport, close enough for shock waves to rattle our Humvees and cover us in dust and sand and debris, sending a mushroom cloud into the sky that eclipsed the sun; I would smile, making my teammates think I was calm in the storm when I was actually grateful that I wasn’t wrestling Hillary Clinton again: nothing shocked me more than being slammed to the mat by that beast.

The impact sent a shock wave that reverberated back from the bleachers, and I felt that, too. Had I wind left in me, it would have bellowed out. Everything went dark, but my body acted on its own and bridged so quickly that Hillary didn’t get the pin. My feet planted the rubber soles of Craig’s Tigers flat on the rubber mat, and my long lever legs pushed with everything they had.

The distinction between a reaction and an action is that an action is beneficial, usually conditioned through training until it’s a habit, and something deep inside me planted my feet when my thoughts would not have been fast enough. Some philosophers and religious folks say that the distinction between the two is where the subconscious or God is present; if so, Mother Earth reached through Craig’s shoes and gave my legs strength, and they pushed with a force greater than I had ever known possible. My neck muscles, strengthened by nine months of weight training, quivered under Hillary’s efforts to mash me down, but somehow my body kept fighting and my shoulders hovered a few inches above the mat. My eyes, now seeing light after the shockwave dissipated, stared to the trellised roof high above the gym floor. I tried to breathe but could not.

Hillary went onto his toes and put almost all of his 147 pounds onto my chest, though it felt like all of the football team had piled on, too. Not even Yoda could have moved him. Hillary squeezed his massive hairy arms with the patience of a boa constrictor, bit by bit, waiting for the slightest exhale to squeeze a bit more. His tightening was controlled, calm, and deadly, a disciplined and dispassionate sniper who took calculated shots at the peak or valley of breaths. I tried force my right hand between our chests, making a tight fist so that its gnarly knuckles would rasp across his rib cage and cause enough pain for him to loosen his hold, but he only exhaled and pulled himself closer to my spine, compressing my ribs even more. I was burning precious fuel and my bridge began to buckle, so I stopped fighting and focused on saving energy.

I couldn’t move. Frozen in space, I stared at the clock. There was almost a minute left. I could see Coach and Jeremy watching me in silence, and Paige and a gaggle of blue-hooded Bengals violating rules by leaving the bleachers and watching from the floor behind our corner. I didn’t pray. Like I said, I’ve never been a religious person, and thinking takes up energy better spent wrestling, even if wrestling motionlessly. I put everything I had into bridging and waited.

I could feel and see, but no air was coming into my nose for me to smell anything. I couldn’t smell the fungicide, which would have been fresh after the gym was rearranged and cleaned for finals, nor could I smell Hillary. He had held me down seven times that year, and I knew his smell intimately from having been held in a headlock by him several times, especially when he caught me in a head throw at the Robert E. Lee High School Invitational, where his bushy armpit covered my nose and I took in deep breaths for almost thirty seconds before I heard the referee slap the mat and call my pin. It’s a scent you never forget, like burnt roux at the bottom of a cast iron skillet, or black tea burnt on an electric stove; it’s a smell you never forget, and the absence Hillary’s familiar pungency was just as a poignant in my mind.

In my periphery, gathered in the public space behind Coach and Jeremy, about half of Belaire’s team gathered to watch, a few of them knowing me since elementary school, when they picked on me and called me Dolly, like the big bosomed country singer Dolly Parton, an inevitable nickname for a kid named Jason Partin, but who had nominated me for captain the year before.

But what was most remarkable were the all-city wrestlers from the previous summer freestyle camp, the same ones who wrestled on the all-Louisiana team during summer junior olympics and called me Magik, with a “k” to differentiate it from Magic Johnson or the newly formed Orlando Magic basketball team, which had just stolen Shaquelle O’Neal from LSU. He was seen around town in a custom Mercedes, cut and re-welded six inches longer and taller to host his long legs and torso; it was rumored he wore a size 22 shoe, and he and the Orlando Magic were the talk of Baton Rouge in 1989 and 1990. They all wore different colored hoodies to represent their teams, but they were aligned with the sport of wrestling more than any arbitrary school color.

About six of the all-city wrestlers gathered behind the Belaire guys, all wearing the same white t-shirt over their different colored hoodies. Only Chris Forest, heavyweight for the Baton Rouge High Bulldogs, wasn’t wearing one; he couldn’t squeeze his broad torso into an XXL. Next to Chris and two feet shorter was Clothodian Tate, the Bulldog’s captain and 136 pound champion. The summer before, Clodi’s dad, a minister, found the t-shirts in a Christian supplies store under the I-110 overpass near LSU, just were it branches off of I-10 and where a few small shops sprouted up under the rumble of Teamster trucks overhead. The shirts were simple white shirts printed with Ephsians 6:12 in an unremarkable font, but the message wasn’t about religion for most of us, it was about wrestling because it said:

“For we wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places.”

My flesh was out of oxygen, but my body somehow kept wrestling with whatever fuel was left for it to fight against darkness. I began to hear the beginning of “Lunatic Fringe” in my mind, but I was too focused on wrestling to wonder how. The guys in my corner began to fade into one dark grey blur, and the clock became a single spot of fuzzy orange light at the end of my tunneled vision. Lunatic Fringe transitioned from the opening riff into the slow opening lyrics that spoke of seeking:

Lunatic fringe

I know you’re out there…

The acne on my back protruded further than my tight singlet and I could feel the bumps contact the mat and push against my skin. The orange light dimmed and then vanished, and I don’t recall hearing the second verse of Lunatic Fringe. But I saw the referee’s blurry face when he slid beside my head with his whistle pinched between his lips, and I felt skin contact rubber. I heard a whistle and the slap of a hand against the mat, and my vision quest was over. Hillary Clinton had won.

We stood up and the referee raised Hillary’s hand. The applause and stampeding of feet on the bleachers shook the gym more than the bomb that had gone off earlier. It was a beautiful throw, and Hillary earned his win. The Louisiana High School Athletic Association recorded that he pinned me at 3:40, twenty seconds to go in the second round, and those records persist in LHSAA.org archives for the world to know that Hillary won the gold, and that Clodi won most outstanding wrestler, which no one argued; had Clodi been fifteen pounds heavier and a couple of years older, he may have beaten Hillary; in two years of practice with Clodi, I never once scored on him.

I walked to Belaire’s corner. Coach stuck out his right hand and took mine. His other stubby but ridiculously strong hand reached up and clasped my left tricep. He looked up into my eyes, his squat but unflappable stance now permanent part of how he stood, and he said: “Good job, Magik.”

Jeremy offered me a fresh hand towel. He was a man of few words but of kind actions who never agreed with the team’s decision to make me co-captain, but he stood up and offered the chair next to Coach. Surprised, I accepted the towel and sat down. He had nothing to prove with his gesture; he was the champion, not I. Jeremy stepped behind me and into the corner that was now empty; a quick glance let me see our team back in the bleachers with their parents, and I turned around and sat beside Coach. Another wrestler was on deck. I had a job to do, and nothing else mattered for the next six minutes.

Later that day, a few of us were helping the Bulldogs clean up their gym. I couldn’t help much, because my finger had a splint from the medic and I had kept a bag of ice from the concession stand on it for an hour or so. Instead, I stared at the blank clock, powered off but still foreboding if only because of it’s bulk handing over our heads. I heard laugher I recognized, and in my periphery I saw Pat, a former Bulldog heavyweight and now their assistant coach, standing with a few other coaches and Andy and Timmy, the burly twins who still called me Dolly. They were laughing with a small group of other old-timers with Pat, who volunteered at the downtown camp and who, like Chris Forest, couldn’t squeeze into an XXL shirt.

“Hillary stuck Magik so hard,” Pat said in a playful tone, “the only thing he could wiggle was his eyeballs.”

Pat wiggled his eyeballs and everyone laughed; he set up that joke every time someone was pinned. I had seen him do it a million times. I would have laughed again, too, had I not been so focused on the timer. I was thinking about how it faded from my vision, and wondering how I was unable to remember the exact moment I stopped being able to see it. What happened in the ten or so seconds I couldn’t recall? I acted according to my conditioning, but where was I while it was happening?

My mind was blank. I wondered how I had heard Lunatic Fringe; it was the first time I observed thoughts or mental objects acting independent of me, something that would happen again and again in the first Gulf War and many missions thereafter when I was fatigued and acting on autopilot; but you never forget your first time. It’s confusing until you get used to it.

The laughter dissipated and the gaggle of wresters and coaches parted. In my periphery, I saw Pat’s smile go away. He leaned down and softly asked Coach: “What happened? Magik almost had him pinned. He was focused all season. It looked like he gave up. Is he okay?”

Coach replied that I had a lot on my mind, and that my grandfather was sick. Coach was a man of few words; Jeremy was loquacious compared to him. He put the reading glasses he kept draped around his neck onto the tip of his nose, glanced down at the clipboard he always carried, and waddled away to help someone do something.

After he left, Pat glanced towards me. Everyone had seen the news: Edward Grady Partin was released from prison early because of declining health, diabetes and an ambiguous heart condition, and he wasn’t expected to live long. It had been in the paper almost weekly all season, but Pat was caught up in the tournament and had forgotten. He looked away and hustled off to see if he could help Coach.

My grandfather died a week later; I would attend his funeral with my two left middle fingers buddy-taped and Hillary Clinton fresh on my mind.

Go to the Table of Contents

- From “Hoffa: The Real Story,” his second autobiography, published a few months before he vanished in 1975:

“But there’s another Edward Grady Partin, one the jury never got to hear about.

This Edward Grady Partin is mentioned in criminal records from coast to coast dating from 1943, when he was convicted on a breaking and entering charge, to late 1962, when he was indicted for first-degree manslaughter. During that twenty-year period Partin had been in almost constant touch with the law. He had had a bad conduct discharge from the Marine Corps. He had been indicted for kidnapping. He had been charged with raping a young Negro girl. He had been indicted for embezzlement and for falsifying records. He had been indicted for forgery. He had been charged with conspiring with one of Fidel Castro’s generals to smuggle illicit arms into communist Cuba.”

Hoffa’s version of my grandfather wasn’t propaganda or hyperbole; to be forthwright, the FBI director of Hoover’s “Get Hoffa” task force, Walter Sheridan, focused on my grandfather’s backgreound in his bestselling 1972 opus, “The Fall and Rise of Jimmy Hoffa” – coincidentally published the month I was born. Of the hundreds of names detailed in the appendix, my grandfather takes up space second only to Hoffa. I trust Walter. He wrote:

“Partin, like Hoffa, had come up the hard way. While Hoffa was building his power base in Detroit during the early forties, Partin was drifting around the country getting in and out of trouble with the law. When he was seventeen he received a bad conduct discharge from the Marine Corps in the state of Washington for stealing a watch. One month later he was charged in Roseburg, Oregon, for car theft. The case was dismissed with the stipulation that Partin return to his home in Natchez, Mississippi. Two years later Partin was back on the West Coast where he pleaded guilty to second degree burglary. He served three yeas in the Washington State Reformatory and was parolled in February, 1947. One year later, back in Mississippi, Partin was again in trouble and served ninety days on a plea to a charge of petit larceny. Then he decided to settle down. He joined the Teamsters Union, went to work, and married a quiet, attractive Baton Rouge girl. In 1952 he was elected to the top post in Local 5 in Baton Rouge. When Hoffa pushed his sphere of influence into Louisiana, Partin joined forces and helped to forcibly install Hoffa’s man, Chuck Winters from Chicago, as the head of the Teamsters in New Orleans.

↩︎