Wrestling Hillary Clinton: A Memoir

But then came the killing shot that was to nail me to the cross.

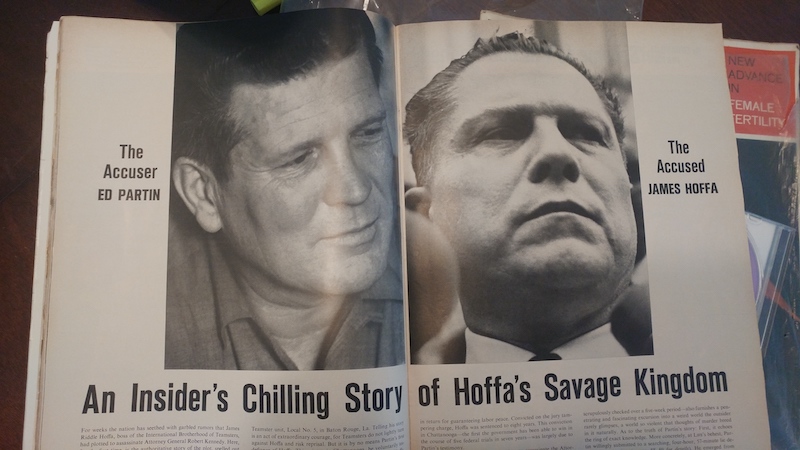

Edward Grady Partin.

And Life magazine once again was Robert Kenedy’s tool. He figured that, at long last, he was going to dust my ass and he wanted to set the public up to see what a great man he was in getting Hoffa.

Life quoted Walter Sheridan, head of the Get-Hoffa Squad, that Partin was virtually the all-American boy even though he had been in jail “because of a minor domestic problem.”

– Jimmy Hoffa in “Hoffa: The Real Story,” 19751

I’m Jason Partin. Thirty four years ago, Hillary Clinton broke my left ring finger just below the middle knuckle. It healed askew, creating a gap between my ring and middle fingers that, to this day, looks like a split-finger salute.

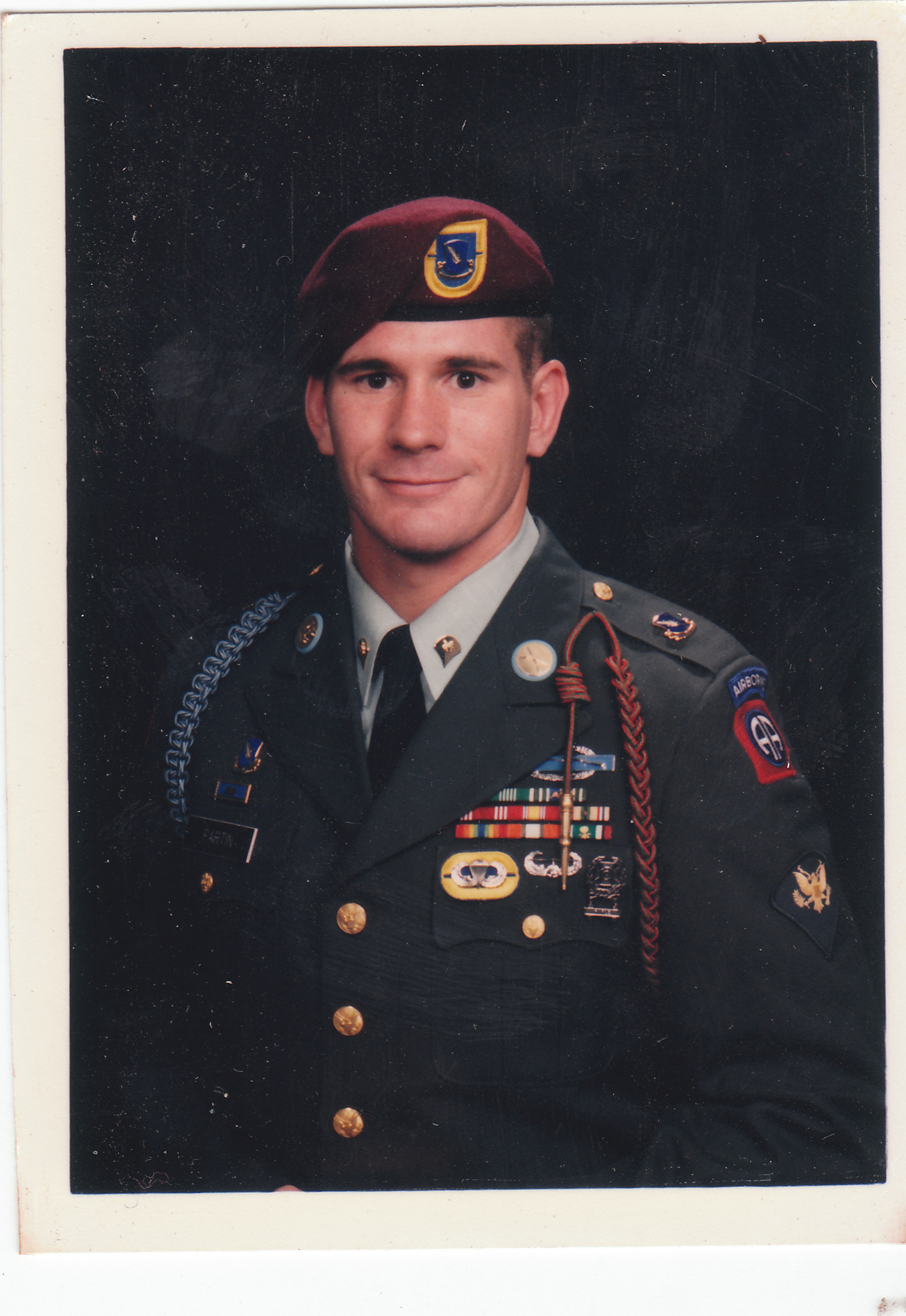

I’m a close-up magician, so for most of my life people have stared at my hands, and many have asked about that finger. When I say Hillary Clinton broke it, they usually laugh and assume it’s a joke, but it’s not. The Hillary in this story was the three-time undefeated Louisiana state wrestling champion at 145 pounds and captain of the revered Capital High Lions, and he broke my finger and then pinned me in the second round of the Baton Rouge City finals tournament on Sunday, 03 March 1990, when I was co-captain of the Belaire High Bengals, 17 years old and about to leave for the army. I wouldn’t hear about President Bill Clinton and his wife, Hillary Rodham Clinton, until Bubba was elected in 1992, when I would, coincidentally, serve two years on his quick-reaction force as a small-team leader with the 82nd Airborne, America’s Guard of Honor.

The joke in high school was that Hillary was like Sue in Johnny Cash’s song, “A Boy Named Sue,” a kid who grew up tough and mean because of his name. But he wan’t mean; he was terse and intense, focused on training harder than any wrestler I knew, but he wasn’t mean. He was born in March of 1971, and at the end of the 1989-1990 wrestling season he was a legal adult in high school and about to turn 19, and had been shaving since at least the 11th grade. At weigh-in before each match, referees checked our faces and forearms for stubble and our legs for Vaseline, because some wrestlers shaved a few days before a match to make their chins and arms abrasive like sandpaper, or rubbed Vaseline to their legs to make them slick and hard to grasp. But Hillary didn’t cheat. He shaved his face smooth each morning before competing, and his stout hairy forearms were so strong that he could cross-face anyone without needing stubble. If someone grabbed his leg, he cross-faced the hell out of them and they let go.

USA Wrestling rules added two pounds to each weight class after Christmas to account for growth. By March of 1990, Hillary, though only 5’4″, was fully grown, so his extra two pounds were pure muscle put on by lifting weights, and he was a 147 pound hairy terror. His burly arms were proportionate, not gangly like a lot of growing teenagers, so his body didn’t waste precious pounds on an otherwise useless extra inch of arms or legs. His thighs bulged with muscles and his lats were wide, so to fit into his elastic wrestling singlet he had to wear a larger size than his lean stomach needed, and the singlet looked like a maroon-colored second skin painted over his dark black body, but with loose folds around his tapered waist.

Like a lot of us, Hillary had to sweat off a few pounds before each match. Capital High was next to the downtown 34 story art deco state capital building, the tallest in America back then, an architectural gem built during the depression by Governor Huey Long, Louisiana’s Kingfish, when labor and materials were cheap; the Kingfish’s photo still hangs at the top of the stairs by the bullet holes that killed him when he was a senator about to become president, and it was the tallest capital building in all of America and the tallest building in Baton Rouge. Practically every kid in Baton Rouge toured the capital in middle school, and we’d see high school wrestlers from the downtown training camp running up and down the steps like Sylvester Stallone in the film Rocky. When I became one of those high schoolers, I saw Hillary wrapped in big black plastic bags, running up and down the steps every Friday before Saturday weigh-ins, sweating off a few extra pounds.

Capital High was – and is – a mile from the state capital building. It was in what most people called a bad part of town, an overwhelmingly African American community under the I-10 and I-110 interstate overpasses that criss-crossed around our capital building, part of the urban poverty islands created by America’s interstate system in the 1950’s and 60’s. I, like most other white wrestlers, only ventured there because of the nearby all-city wrestling camp. I never learned his midweek weight, but Hillary was probably around 155 pounds before fasting for a couple of days and sweating off the last pound or two. Once, I saw him running while spitting into an old 16 ounce Gatorade bottle, cutting another pound by not swallowing for hours.

I was the opposite. I was born on 05 October 1972, so I began my senior year as a 16 year old kid. Had I been born a few days later, by Loiusiana law I would have been to young to start kindergarten, so I would have been pushed back and began kindergarten a year later, starting school at five years old instead of four, and my senior year at 17; I would have been 18 for city finals, and much larger and stronger. Instead, I was 5’6″, two inches taller than Hillary, but a lanky mid-pubescent kid with disproportionately long arms, wide hands with long knobby fingers, and scuba fins for feet. My singlet was skin tight and pulled taunt by my long torso.

I had negligible underarm hair, and my pale face and shoulders were dotted with bright red pimples. I had never shaved. Unlike Hillary’s leg and forearm hair, which was thick and curly like the Brillo pads my Granny used to clean her cast iron skillet, the hair on my arms and legs was soft like the fur on a puppy. My hair was close-cropped on the sides, almost like in the army, but a bit longer in the back, like a mullet style awkwardly popular in the 80’s; mine was more to hide an 8-inch long scar on the back of my head, a finger-width thick and shaped like a big backwards letter C. Though young, I had strong legs from jogging the state capital steps and hiking the hills of Arkansas with dad most summers, and my cross-face was decent because when I pushed my fist across someone’s face my bulbous thumb knuckle caught and opponents nose and hurt more than forearm sandpaper ever could. I was rarely taken down by a shot; my Achilles Heel was a lack of upper body strength, and I was vulnerable to throws and bear hugs by burly opponents like Hillary.

When I read Outliers and put Matthew 13:12 in context, I instantly thought of Hillary shaving when I was getting my first pimples. A 2008 book by Malcolm Gladwell, “Outliers: The Story of Success,” centers around a Canadian study investigating why, statistically, more professional hockey players are born in March than any other month. They, like Hillary, started each year of school as the oldest kids in class, and the difference between four and five years old is more than 20% of life, it’s a leap along an exponential curve of physical and mental development that continues and grows with each year, especially in a system that categorizes and groups kids according to abilities, creating a self-fulfilling prophesy few people notice. Malcolm called that advantage “The Matthew Effect,” after the New Testament’s Matthew 13:12, where Matthew wrote something like:

Whoever has, will be given more, and they will have an abundance; whoever does not have, even that will be taken from them.

But I was lucky. If I had anything in abundance, it was what my teammates called tenacity, a trait demonstrated by getting back on the mat against Hillary no matter how badly he beat me. I inherited tenacity – but not large size and natural strength – from my biologic father, a burly street brawler and drug dealer, who inherited it from his father, a former heavyweight boxer with a criminal record you could write a book about.

Because of a quirk in the law, I was also a legal adult in 1989. A week after my great-uncle Bob’s funeral on 03 August 1989, the coincidentally named Judge Robert “Bob” Downing of the East Baton Rouge Parish 19th Judicial District granted my request to be emancipated from my family. The justice system of Louisiana based on the Napoleonic Code from when Louisiana, named after King Louis and Queen Anna of France, was a French colony. The code persisted after the Louisiana purchase and then the civil war, stubbornly clinging to law books and making Louisiana have a judicial system unique among all United States, just like it is still divided into Catholic parishes rather than counties like in every other state. Under Louisiana’s code, Judges have more leeway and rely less on predicate cases from the U.S. Supreme Court, so Judge Bob could practically do what he wanted. He told me what I had to do, and I began the paperwork as Uncle Bob lay dying.

Judge Bob already knew my family well, especially my dad, Edward Grady Partin Junior, from when he was first arrested at age 17 and I began bouncing in and out of the Louisiana foster system, spending some months with the Partins and some with my mom and her family, Uncle Bob and Auntie Lo. East Baton Rouge Parish had only one family court judge, and our cases were discussed when a new judge took over. Judge Bob’s predecessor, Judge Pugh, had first removed me from Partin custody; he died soon after by alleged suicide. Pugh was replaced by Judge J.J. Lottinger, who transferred from 30 years in state legislation and retired in the early 80’s; Judge JJ passed the torch to Judge Bob, who presided in the summer of 1989. After I filed the paperwork and paid the fee, he interviewed my mom and answered my prayer by stamping the raised seal of Louisiana – a Pelican nesting her babies above the words “Union Justice Confidence” – on an emancipation decree slightly larger than a sheet of legal paper.

My girlfriend, Lea, a film buff a year older than I was and nicknamed Princess Lea, like in Star Wars, picked me up and drove me from the courthouse to the army recruiter’s office, where I held up the certificate that said I was a legal adult. I signed a contract and began the army’s delayed entry program. I was guaranteed $36,000 for college from the GI Bill, and an assignment with the 82nd if I passed Airborne school. The contract depended on me graduating high school, passing the ASVAB test, and not being found guilty of a crime. If I were arrested, Judge Bob had emphasized, I’d be charged as an adult and go to jail, just like my dad and his father, and not even he could help me.

I was average in academics and strength for a 17 year old, but I was persistent and would show up to practice early and stay late, teaching basic wrestling moves to 250 pound football linebackers nearly as strong as Hillary so that I could practice my defense. I weighed around 152 midweek, and I fasted one to two days before weigh-in. Sometimes Lea drove me to the downtown wrestling club and I joined other wrestlers tackling the state capital steps sweating off a few pounds and building leg strength; Baton Rouge is a flat city barely above sea level, and the capital building was the only place we could run uphill unless we did laps on football bleachers, which became boring after an hour or so. Sitting in class on Fridays, I ducked my head down and subtly spit into a Gatorade bottle I held between my legs.

When Coach noticed me training extra hard, he showed me how to be more efficient by using my gangly arms and legs as fulcrums with the cradle, wrapping my long arms around an opponents neck and a leg, locking my hands, and bringing their knee to their face and rolling their shoulders to the mat. I learned that I could pin even the linebackers once I clasped my hands. Thanks to Coach, I grew to have the strongest cradle in all of Baton Rouge, maybe even in all of southern Louisiana.

The trick was to not clasp both hands together like a handshake, but to lock them with thumbs flat against the first fingers (Coach said: “A wrestler looses 15% of his grip strength if his thumb is out”). And, instead of squeezing harder and straining against a stronger opponent (“An opponent’s legs are stronger than your arms”), Coach showed me how to bring my elbows together by focusing on moving my hands away and using my long arms as fulcrums, like how pivot points of a bolt-cutter amplifies your strength and cuts through steel. I began pinning teammates the same day he showed me that trick, and I didn’t stop all year.

To get even stronger, I took Coach’s advice and began crumpling the Baton Rouge Advocate one page at a time, forming tight balls and dropping them on the floor until there was a hill of paper balls and my forearms were screaming for me to stop. I used my duct-taped handgrips in school, oiling the springs so I could exercise under the table without teacher’s hearing squeaks, and when I wasn’t in school I crumpled every newspaper I could find, leaving my blue Belaire hoodie stained with black fingerprints. The bulky Sunday edition was dedicated to the end of tournaments, when I’d have a few days to recover before Wednesday’s dual meet. I’d save the comics for last and read them above a pile of crumbled paper balls in Coach’s floorboard.

When Uncle Bob was sick and I couldn’t train at the downtown camp, Coach picked me up once a week and I rode with him along the serpentine River Road between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, dropping off five-gallon jugs of inexpensive fungicide at Region I schools even smaller than Belaire and stopping at St. Paul’s in Covington, where Coach would say hello to his son, Craig. His team had more Creoles, the olive-skinned decedents of Caribbean slaves and mostly Spanish rulers who lived in New Orleans, than the Belaire team, which was closer to Lafayette and therefore had more Cajuns, the mostly caucasian decedents of around 6,800 French exiled from Canada after a war with the British, but with a dark tint from mixing with Native Americans in what we now call Acadia. Coach and Craig would hug and then chat about Louisiana wrestling, and then Coach would take me to Jesuit High School, where Coach would chat with Coach Sam, a diminutive Japanese champion of both wrestling and judo, and I’d train for an hour with their second or third string team while the first-string was off winning national freestyle tournaments. Sweaty and with scrapes on my cheeks from Jesuit guys dragging my face across the mat, I’d ride back with Coach and work on my cradle-locking hand strength. The drive was about an hour and a half, enough for at least one Advocate to be transformed into a pile of compacted paper balls the size of golf balls. At least once every week or two, I’d see a photo of my grandfather, and on those days I crumpled the balls even tighter.

By March, teammates quipped that I had a kung-fu grip and was stronger than I looked. They began to believe that I could actually beat Hillary, and they rallied to help. Though I was co-captain, they took charge and played a modified version of King of the Mat, insisting I remain on the mat even if I were taken down. After an hour, I was so weak that even Little Paige could topple me.

No matter who took me down, I’d raise one knee and put both hands on it and force myself back up to face each fresh wrestler. The game would continue until Coach made us quit so he could turn off the lights and go home to Mrs. K. I was in remarkable physical condition. I had a kung-fu grip and the focus of a sniper’s scope; a few months later, I’d consider basic training, advanced infantry school, and Airborne school trivial by comparison, a sentiment shared by other wrestlers I met in service. Some of us would sneak in extra pushups after lights-out to stay in shape.

Armed with physics and with Coach in my corner, I clawed my way from loosing all 13 matches my sophomore year to finishing my junior year 76-35. By the city tournament my senior year, I had an impressive record of 56-12 and was ranked third; though I had never competed in finals except for smaller tournaments like Coach’s Thanksgiving and Christmas tournaments, when many wrestlers took a break from fasting to be with families. Hillary had been captain for almost three years, and his senior record before City was 45-0.

For the first time in my high school career, I was a guaranteed silver medal and had a chance for the gold. By then I had 36 pins, most with the cradle.

I don’t know what Hillary thought of my cradle, because we had never spoken. As co-captain, I stood beside Jeremy Gann, the other Bengals co-captain, and we faced Hillary before every pre-tournament meeting and dual meet, shaking hands in front of spectators to represent the fair play each of our teams promised, but we didn’t chat. We never spoke at the state capital steps when we ran with other equally terse wrestlers, and I never saw him at the downtown all-city training camp. Despite Capital High being jogging distance to the downtown wrestling camp, the Lions kept to themselves and didn’t train with the mostly caucasian all-city team, with only Clodi and Chris standing out among us. In hindsight, it’s easy to see why: the capital is surrounded by civil war barracks and the original LSU campus, called “Old War School,” which supported the surrounding plantation homes by training military leaders to preserve slavery. Governor Huey “Kingfish” Long built the state capital and then drained the nearby swamps to build today’s LSU, keeping the original LSU as a museum to “The Old War School,” showcasing where southern gentlemen trained as officers in the confederate army. In the state capital lobby a plexiglass display protects bullet holes from when The Kingfish, by then known as presidential candidate and U.S. Senator Long, was assassinated by his bodyguard, a tribute every middle school kid who takes a field trip sees and hears about; surrounding the capital grounds are buildings pot-marked with bullet holes from what one of my teachers once quipped as “The War of Northern Aggression,” though no plexiglas protects them and there’s no sign telling you why they were there. From the crow’s nest atop the capital, we stand atop the tallest skyscraper we could imagine and peer upriver towards Saint Francisville and see Fort Pickens, site of the longest battle of the civil war, where Baton Rouge soldiers trained by officers from The Old War School fought 378 days to preserve their way of life. It’s no wonder Hillary looked so intense when he ran up and down the state capitals 34 flights of stairs again and again.

Baton Rouge High hosted City in 1990. I won my first three matches, two on Saturday and one on Sunday, winning that match 3-2 and upsetting the number two seed, Burly’s captain, Frank Jackson, in semifinals. The gym cleared and Baton Rouge High Bulldogs rearranged the mats to have just one in the center. People paid $2 to come back inside and see final, and bought food from a small concession stand to raise money for things like free fungicide and ear guards. Coach’s daughter, Penny, an Iowa girl, worked the concession stand when she wasn’t taking classes at LSU, and sometimes Mrs. K was there to support us. I, like a lot of wrestlers, would nibble on a slice of pizza after weigh in, smile around Mrs. K, and stick out our chest and square our shoulders around Penny, who sometimes offered tips on technique. She was impressed that I held Frank, who was almost as burly as Hillary, in a cradle for almost a full minute in the final round; apparently, he was giving everything he had to break it, which is why the referee didn’t call either one of us for stalling.

I left Coach’s side and began warming up with Clodi. He was 136 pounds, but seeded first and likely to pin his opponent quickly. Jeremy was also seeded first, but he had faced the second seed a few times and they were closely enough matched that he could be pinned. I wanted to ensure I was warmed up, just in case. Clodi silently stretched in his green hoodie, and I skipped rope in my blue and orange one.

I listened to a mixtape on my old Sony Walkman that included songs from the 1985 Vision Quest soundtrack. I had a CD player by then, the one given to me by Uncle Bob before he passed, his final gift to support me when spine cancer kept him bedridden, but back then there weren’t CD burners to make custom playlists like we could with dual-cassette boom-boxes, and even the best CD players skipped when I jumped rope, so for tournaments I still listened to my Walkman and a mixtape Lea helped me make. We picked songs like “Lunatic Fringe” by Red Rider and “Hungry for Heaven” by Rio, both from Vision Quest, and “Panama” from Van Halen’s 1985 album aptly titled “1985,” because I thought the album and David Lee Roth were awesome (I was one of the kids who took David’s side when Sammy Hagar replaced him for the 5150 album). I knew the lyrics by heart, and as I watched the mat my mind sang along in a ritual I repeated around 50 to 60 times a year.

I alternated tracks with a few of the new electronic jams that helped me skip rope more quickly, like “Don’t Stop the Rock” by Freestyle. That was because Dana “Big D” Miles, our 275 pound heavyweight and beat-boxer in the spirit of The Fat Boys, said I should develop more rhythm, like Sylvester Stalone learned from Apollo Creed’s trainers in Rocky III. I said I’d try, and every time the chorus of “Don’t Stop the Rock” came up I criss-cross my hands and skipped my feet to the beat:

Freestyle’s kickin’ in the house tonight

Move your body from left to right

To all you freaks don’t stop the rock

That’s freestyle speakin’ and you know I’m right.

da, da, da-tada-da-ta

da, da, da-tada-da-ta

da, da… tada-da-ta

I skipped and breathed slowly and coaxed out a thin sheen of sweat, transitioning my body to burning the tiny bits of fat tenaciously clinging to a few muscles. I kept one eye on the mat to ensure I didn’t miss my match, a risk to anyone wearing headphones who likes to warm up alone. Clodi won by pin in the first round, then Jeremy won by points after all three rounds. I pushed the stop button on the Walkman, jogged to the chair beside Coach, took off my hoodie, and handed the Walkman and jump rope to Little Paige, our freshman 103 pounder. Jeremy took his seat next to Coach. A handful of Bengals in blue hoodies gathered by the bleachers about ten feet behind them.

I put on my headgear and trotted to the center of the mat, shaking my arms and moving my legs. The referee stood beside us as we put our lead feet on the line and faced off. He asked us to slap hands, a handshake of sorts to encourage fair play. He stood back with his whistle in his mouth and his hand raised, and suddenly dropped his hand and blew his whistle, and both of us were in motion before the sound waves reached spectators in the upper bleachers.

We collided so hard the gym rafters rattled; a minute and a half later, we were drenched in sweat and Hillary was up 3-1. My heartbeat was racing and my breath was deep and faster than I could sustain, but Hillary seemed the same. We were near the center, an arm’s reach apart, and he tapped my head to temporarily block my view and allow him to shoot a low single. I was watching his hips and was therefore undistracted by his tap, and I sprawled and cross-faced him and spun behind; instantly and automatically, my right arm shot around his neck and my left arm slid under his leg, and I clasped my hands and had a cradle on Hillary for the first time.

I only had a moment to savor the feeling, because his muscular leg began kicking against my hands with the cadence and urgency of 1-2-3 chest compressions on a dying teammate in the midst of battle. Hillary was fierce and relentless, and I felt my teeth rattle with each of his kicks.

My sweaty hands began to slip apart. Soon my right hand was clasped only my left ring and pinky finger. He kicked again, and my left thumb slid too far away from my grip to do any good. I clamped on with my kung-fu grip like I was dangling from a rope and would die if I let go. He kicked again, and I felt my ring finger snap.

Of course it hurt like hell, but I was too focused to pay attention to anything but grasping at a win I felt was close enough to smell. I clung on with my right hand with all the tenacity I could muster, but he kicked again and Hillary broke free and stood up and turned to face me with the speed I had grown to respect. We were face to face again, his strongest position, and his bushy eyebrows furrowed with anger. I had never seen him angry on the mat before, and I only had the smallest fraction of a second to realize that before the buzzer sounded. The referee awarded him an escape point, and me a takedown without back points, which required holding them with control for at least two seconds. I was down 4-3. The ref pointed us to our corners. I had lost a chance: people make mistakes when they’re angry.

Jeremy was beside Coach and ready with a fresh hand towel that smelled of fungicide, like everything carried in the back of Coach’s truck. I wiped the sweat from my eyes, only to have more pour down my forehead, pool in my eyes, and drip off my nose and chin and splash on the mat by my shoes. I alternated between shaking my limbs to stay limber and dabbing sweat off my face, mindful of the break on my ring finger, swollen to a useless rigid plank. Coach asked, and I said I was fine. He nodded his acorn-shaped head, briefly showing the bald poking through his whispy grey hair, and stepped back. I kept my focus on Hillary; I wanted to face him while he was still riled and I was calm.

My breath whooshed in and out through pursed lips while I stared at Capital’s corner, hoping for a glimpse of the strategy he’d apply in our next round. Two of the maroon hooded Lions dried each of Hillary’s arms while he bounced and shook his limbs like a mirror image of me. They were always intimidating with their black skin hidden under the dark hoodies, especially when they trotted onto the mat to warm up as a team, following Hillary and lined up 103 pounds to the 275 pound heavyweight like a row of black and maroon Russian Matryoska dolls trotting in a synced rhythm that reverberated in every gym they visited. Once a year we competed in the Lion’s gym, like the one Daniel was tossed into, a dilapidated and asbestos padded room with peeling maroon paint faded and duct-taped mats. The doors were adorned with crudely painted but obviously adored murals of a gold Lion of Judah in the red, yellow, and green colors of the Zulu parade in New Orleans. The Lion’s Den bleachers were always filled with parents and neighbors who could walk there, and who stomped their feet to the rhythmic beat of Hillary and the Lions jogging in a circle on the mat to warm up.

I stood on the Bulldogs new, bright green mat and ignored the maroon-hooded Lions circling Hillary as if to shield their captain from distractions. I focused on their coach, a spherical mountain of an African American man who couldn’t squeeze into even the largest of sweatsuits. I tried to decipher his hand gestures, hoping for a hint of help against Hillary.

The Mountain had never wrestled and the Lions never participated in all-city practices, so many of their signs were different than any other school I knew. Hillary nodded after every one of The Mountain’s gestures. Coach and Jeremy let me be. My cradle was useless, but there was nothing I could do about it. All that mattered was that my breath stabilized and my heartbeat calmed down. I bounced and shook my arms gently to keep them warm and to maintain a sheen of slippery sweat on my legs, a tiny advantage that no one would consider cheating. The Mountain kept lowering his hand, as if telling Hillary to calm down and focus; in hindsight, he was probably telling him to not shoot on me again, to focus on his strengths and my weaknesses.

The referee called to us a few brief seconds later, and I trotted back to the center of the mat. Hillary won the coin toss, and he gave two thumbs up to indicate he wanted us both standing in neutral position. We put one foot forward and faced off. The referee stood poised, whistle in mouth, and raised his hand. I focused on Hillary’s hips.

Coach only gave a handful of nuggets of wrestling advice in the three years I had known him. One was to watch an opponents hips, not their eyes or hands, because where their hips went, they went. You can fake hand motion to get someone to react, and you can misdirect them with where you stare, but your hips belie where you will go. That was advice from an Iowa coach when Coach was an alternate on the olympic team, at a time when Russians dominated international wrestling because they focused on taking an opponent off their feet, setting up throws with taps to the head that provided just enough distraction for them to penetrate your defenses and get close enough to pick you up. Coach told the same story once a year, at the beginning of practice, practically without change.

“But to do that,” he explained slowly, getting eye contact with each of us before continuing, “they need to get their hips close to yours. Get you to overreach, so they can step in close.”

He paused to let that sink in, then raised a stubby finger and said, “The Russians realized that if you break a man’s stance, you can do what you want to him.” He put down his finger, and said: “Don’t break your stance.”

“Here!” he said, jumping into a gravediggers stance.

“It’s like shoveling dirt all day. Or pig slop,” he said.

One wrestler a time, he patiently caught eye contact with each of us before moving again.

“Here!” he said when we were all looking, and he sprawled onto the mat and landing face down but still in that gravedigger stance, one leg closer to his hips than the other, foreshadowing what he’d look like standing. He pushed with his stubby arms and effortlessly popped back up in that same stance.

“Here!” he said again and dropped back down. He asked a few football linebackers watching from the adjacent weight room to pile on, and he popped up again, just as effortlessly. Lea said it was like little wrinkled Yoda lifting an X-Wing from the Degobah Swamp, and that I looked as dumbfounded as Luke.

“Vince Lambarti said that fatigue will make a coward out of anyone,” Coach would remind us two or three times a year, saying that we could run track or swim before wrestling season and use the football team’s weight room when they were done.

It was easy to understand focusing on hips and training in other sports, but Coach’s most persistent piece of advice, repeated before practically every dual meet and tournament, was the real secret and what separates average athletes from champions. His advice boiled down to two simple words: “Just wrestle.” No matter what happened the previous round or that morning or the weekend before, just wrestle. With everything you have left in you, just wrestle.

I once asked Coach to elaborate, and all he said was that his words had roots from the most celebrated wrestler of a generation, Doug Blubaugh, a gold-medal winner in the 1960 Rome olympics who pinned all four opponents in record time. In trials, Doug had barely defeated Coach, winning 4:3 and only in sudden-death overtime, back when matches were a staggering nine minutes instead of the measly six of my generation. Coach lost and dropped to the third place bracket, held only minutes after his loss in semifinals, knowing that if he won he would only be an alternate in Rome in case Doug got sick or injured. Coach sat, fatigued and distracted by his loss, and Doug walked over to him and said: “Someone will win. It might as well be you.”

Just wrestle.

On the mat against Hillary, I forgot about my finger and focused on his hips and prepared to wrestle. Someone will win. For the next two minutes, it doesn’t mater who, just wrestle.

In my periphery, I was aware of the referee’s chest and cheeks; sometimes, they telegraph blowing the whistle and you may gain a fraction of a second of advantage. I saw the referee blow his whistle and drop his hand, and I began wrestling before the sound wave reached the bleachers.

But Hillary was faster, and he shot a high double that caught both my legs. I sprawled, kicking both feet into the air like a bucking bronco and slamming my chest onto his broad hairy shoulders. He resisted my weight like Atlas shouldering the world and tried to pull my legs closer to him, to get his base under mine. But my lanky legs began to give me a mechanical advantage, and sprawl by sprawl Atlas faltered. Hillary’s arms crept further from his body and his head began to bow, and that’s when I cross-faced him with the force of God.

His head turned and he released his grip. My right hand continued moving into a cradle, my body acting from a core with no concept of pain in my finger. I began to spin behind, my gimpy left hand targeting his raised left leg, but he sprung backwards and towards the mat’s edge, and he popped back into a perfect stance.

We kept eye contact and crab-walked back towards the center, a truce-of-sorts wrestlers fall into without discussing it, ensuring we stay away from the edge of the mat and the hardwood floor and bleachers. We were almost to the center when Hillary’s forearm shot to my neck like a praying mantis snags its prey. He yanked my head forward, tempting me to plant all weight on my leading foot.

Hillary had a lethal head-heal pick, but Coach had told us how to stop it.

“Don’t be a headhunter,” he said.

He was given that advice from the US Olympic coach, because the Russians used the same head-heel setup as Capital High. Don’t react mindlessly, like a brute, and grab their head like they want you to: keep your stance, remain calm, and be alert. The 1960 Olympics were at the height of the Cold War, and the Soviets were already sneaking nuclear missies into Cuba for what would almost cause WWIII in 1961’s Cuban Missile Crisis, so the world was watching the Soviets versus Coach and the U.S. team that year, seeing how they’d react; they didn’t, and that’s why everyone came home alive and with new colleagues in the Soviet Union, bonded by a love of something greater than politics.

“To grab your head,” Coach had said, “They must overreach their stance first.” He paused and raised his stubby forefinger and got eye contact with each of us one at a time before continuing: “Keep your stance. Stay calm. Be alert. Wrestle.”

Hillary’s muscular arm tapped my head forward, but instead of planting my foot to resist I went along with the momentum; my hips dropped below his center of gravity, and I swung my left leg beside his right, and flowed into a high-single that took him to the mat faster than thoughts could materialize. But Hillary’s legendary speed was faster than you could imagine; he sprung back up and faced me so quickly that no points were scored either way. We stood face to face again for the briefest of moments, then he moved so quickly that I don’t recall how I ended up in a bear-hug; I probably blinked.

Hillary’s bear hug caught me on exhale, when my lungs almost empty, and he instantly threw me in a perfect throw that would have earned five full points in summer freestyle, where Hillary beat even the Jesuit varsity wrestler year after year. A five point throw is the holy grail, a perfect 360 degree arc with the opponents feet off the mat, and I was trapped in mid-air, off my stance, weakened like Antaeus lifted from Mother Earth by Hercules. Those Russians were right, and I was in Hillary’s control.

The ceiling appeared in my view, and above the bleachers I could see the giant Baton Rouge High scoreboard, a late 1970’s giant neon monster with dozens of small orange lightbulbs that spelled out our names and the schools we represented, and with a massive countdown timer so that people as far away as Texas could see how many seconds were left in each round. I watched my size 12 Asics Tiger wrestling shoes, old and frayed and worn into a dull and dusty grey color, that once belonged to Craig when he was a 171 pounder and Belaire’s first state champion, lent to me by Coach when my already disproportionately large feet grew a bit more over Christmas. I watched those shoes fly through the air above my head and in slow motion and creep past the orange neon lights. Hillary and my names and the names of the schools we represented came into view again. They slowly arced back down, inertia keeping them a bit behind my shoulders and hips. I saw faces of fans staring wide-eyed in awe: it was a beautiful throw. Some people, probably those experienced with wrestling, cringed empathetically, because they knew I was about to hit the mat like a meteor crashing into Earth.

Hillary slammed my shoulders to the mat with a thud that shook the bleachers as if a C-130 Hercules had dropped a 15,000 pound bomb in the gymnasium. Yes, that’s exactly what it felt like. Almost exactly a year later, on 04 March 1991, I would watch two C-130’s drop the Volkswagen-sized bombs onto Khamisiya Airport, close enough for shock waves to rattle our Humvees and cover us in dust and sand and debris, sending a mushroom cloud into the sky that eclipsed the sun; I would smile, making my teammates think I was calm in the storm when I was actually grateful that I wasn’t wrestling Hillary Clinton again. Anything felt better than being slammed to the mat by that beast.

The impact sent a shock wave that reverberated back from the bleachers, and I felt that, too. Had I wind left in me, it would have bellowed out. Everything went dark, but my body acted on its own and bridged so quickly that Hillary didn’t get the pin. My feet planted the rubber soles of Craig’s Tigers flat on the rubber mat, and my long lever legs pushed with everything they had. The distinction between a reaction and an action is that an action is beneficial, usually conditioned through training until it’s a habit, and something deep inside me planted my feet when my thoughts would not have been fast enough. Mother Earth reached through Craig’s shoes and gave my legs strength, and they pushed with a force greater than I had ever known possible. My neck muscles, strengthened by nine months of weight training, quivered under Hillary’s efforts to mash me down, but somehow my body kept fighting and my shoulders hovered a few inches above the mat. My eyes, now seeing light after the shockwave dissipated, stared to the trellised roof high above the gym floor. I tried to breathe but could not.

Hillary went onto his toes and put almost all of his 147 pounds onto my chest, though it felt like all of the football team had piled on, too. Not even Yoda could have moved him. Hillary squeezed his massive hairy arms with the patience of a boa constrictor, bit by bit, waiting for the slightest exhale to squeeze a bit more. His tightening was controlled, calm, and deadly, a disciplined and dispassionate sniper who took calculated shots at the peak or valley of breaths. I tried force my right hand between our chests, making a tight fist so that its gnarly knuckles would rasp across his rib cage and cause enough pain for him to loosen his hold, but he only exhaled and pulled himself closer to my spine, compressing my ribs even more. I was burning precious fuel and my bridge began to buckle, so I stopped fighting and focused on saving energy.

I couldn’t move. Frozen in space, I stared at the clock. There was almost a minute left. I could see Coach and Jeremy watching me in silence, and Paige and a gaggle of blue-hooded Bengals violating rules by leaving the bleachers and watching from the floor behind our corner. I didn’t pray. Like I said, I’ve never been a religious person, and thinking takes up energy better spent wrestling, even if wrestling motionlessly. I put everything I had into bridging and waited.

I could feel and see, but no air was coming into my nose for me to smell anything. I couldn’t smell the fungicide, which would have been fresh after the gym was rearranged and cleaned for finals, nor could I smell Hillary. He had held me down seven times that year, and I knew his smell intimately from having been held in a headlock by him several times, especially when he caught me in a head throw at the Robert E. Lee High School Invitational, where his bushy armpit covered my nose and I took in deep breaths for almost thirty seconds before I heard the referee slap the mat and call my pin. It’s a scent you never forget, pungent like a burnt roux at the bottom of a cast iron skillet, or black tea burnt on an electric stove.

In my periphery, gathered in the public space behind Coach and Jeremy, about half of Belaire’s team gathered to watch, a few of them knowing me since elementary school, when they picked on me and called me Dolly, like the big bosomed country singer Dolly Parton, an inevitable nickname for a kid named Jason Partin, but who had nominated me for captain the year before. But what was most remarkable wasn’t my Belaire teammates, which took cues from Coach by showing up to support those of us who made it to the second day, it was the all-city wrestlers from the previous summer freestyle camp, the same ones who wrestled on the all-Louisiana team during summer junior olympics and called me Magik, with a “k” to differentiate it from Magic Johnson or the newly formed Orlando Magic basketball team, which had just stolen Shaquelle O’Neal from LSU. He was seen around town in a custom Mercedes, cut and re-welded six inches longer and taller to host his long legs and torso; it was rumored he wore a size 22 shoe, and he and the Orlando Magic were the talk of Baton Rouge in 1989 and 1990.

About six of the all-city wrestlers gathered behind the Belaire guys, all wearing the same white t-shirt over their different colored hoodies. Only Chris Forest, heavyweight for the Baton Rouge High Bulldogs, wasn’t wearing one; he couldn’t squeeze his broad torso into an XXL. Next to Chris and two feet shorter was Clothodian Tate, the Bulldog’s captain and 136 pound champion. The summer before, Clodi’s dad, a minister, found the t-shirts in a Christian supplies store under the I-110 overpass near LSU, just were it branches off of I-10 and where a few small shops sprouted up under the rumble of Teamster trucks overhead. The shirts were simple white shirts printed with Ephsians 6:12 in an unremarkable font, but the message wasn’t about religion for most of us, it was about wrestling because it said:

“For we wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places.”

My flesh was out of oxygen, but my body somehow kept wrestling with whatever fuel was left for it to fight against darkness. I began to hear the beginning of “Lunatic Fringe” in my mind, but I was too focused on wrestling to wonder how. The guys in my corner began to fade into one dark grey blur, and the clock became a single spot of fuzzy orange light at the end of my tunneled vision. Lunatic Fringe transitioned from the opening riff into the slow opening lyrics that spoke of seeking:

Lunatic fringe

I know you’re out there…

The acne on my back protruded further than my tight singlet and I could feel the bumps contact the mat and push against my skin. The orange light dimmed and then vanished, and I don’t recall hearing the second verse of Lunatic Fringe. But I saw the referee’s blurry face when he slid beside my head with his whistle pinched between his lips, and I felt skin contact rubber. I heard a whistle and the slap of a hand against the mat, and my vision quest was over. Hillary Clinton had won.

We stood up and the referee raised Hillary’s hand. The applause and stampeding of feet on the bleachers shook the gym more than the bomb that had gone off earlier. It was a beautiful throw, and Hillary earned his win. The Louisiana High School Athletic Association recorded that he pinned me at 3:40, twenty seconds to go in the second round, and those records persist in LHSAA.org archives for the world to know that Hillary won the gold, and that Clodi won most outstanding wrestler, which no one argued; had Clodi been fifteen pounds heavier and a couple of years older, he may have beaten Hillary; in two years of practice with Clodi, I never once scored on him.

I walked to Belaire’s corner. Coach stuck out his right hand and took mine. His other stubby but ridiculously strong hand reached up and clasped my left tricep. He looked up into my eyes, his squat but unflappable stance now permanent part of how he stood, and he said: “Good job, Magik.”

Jeremy offered me a fresh hand towel. He was a man of few words but of kind actions who never agreed with the team’s decision to make me co-captain, but he stood up and offered the chair next to Coach. Surprised, I accepted the towel and sat down. He had nothing to prove with his gesture; he was the champion, not I. Jeremy stepped behind me and into the corner that was now empty; a quick glance let me see our team back in the bleachers with their parents, and I turned around and sat beside Coach. Another wrestler was on deck. I had a job to do, and nothing else mattered for the next six minutes.

Later that day, a few of us were helping the Bulldogs clean up their gym. I couldn’t help much, because my finger had a splint from the medic and I had kept a bag of ice from the concession stand on it for an hour or so. Instead, I stared at the blank clock, powered off but still foreboding if only because of it’s bulk handing over our heads. I heard laugher I recognized, and in my periphery I saw Pat, a former Bulldog heavyweight and now their assistant coach, standing with a few other coaches and Andy and Timmy, the burly twins who still called me Dolly. They were laughing with a small group of other old-timers with Pat, who volunteered at the downtown camp and who, like Chris Forest, couldn’t squeeze into an XXL shirt.

“Hillary stuck Magik so hard,” Pat said in a playful tone, “the only thing he could wiggle was his eyeballs.”

Pat wiggled his eyeballs and everyone laughed; he set up that joke every time someone was pinned. I had seen him do it a million times. I would have laughed again, too, had I not been so focused on the timer. I was thinking about how it faded from my vision, and wondering how I was unable to remember the exact moment I stopped being able to see it. What happened in the ten or so seconds I couldn’t recall? I acted according to my conditioning, but where was I while it was happening?

My mind was blank. I wondered how I had heard Lunatic Fringe; it was the first time I observed thoughts or mental objects acting independent of me, something that would happen again and again in the first Gulf War and many missions thereafter when I was fatigued and acting on autopilot; but you never forget your first time. It’s confusing until you get used to it.

The laughter dissipated and the gaggle of wresters and coaches parted. In my periphery, I saw Pat’s smile go away. He leaned down and softly asked Coach: “What happened? Magik almost had him pinned. He was focused all season. It looked like he gave up. Is he okay?”

Coach replied that I had a lot on my mind, and that my grandfather was sick. Coach was a man of few words; Jeremy was loquacious compared to him. He put the reading glasses he kept draped around his neck onto the tip of his nose, glanced down at the clipboard he always carried, and waddled away to help someone do something.

After he left, Pat glanced towards me. Everyone had seen the news: Edward Grady Partin was released from prison early because of declining health, diabetes and an ambiguous heart condition, and he wasn’t expected to live long. It had been in the paper almost weekly all season, but Pat was caught up in the tournament and had forgotten. He looked away and hustled off to see if he could help Coach.

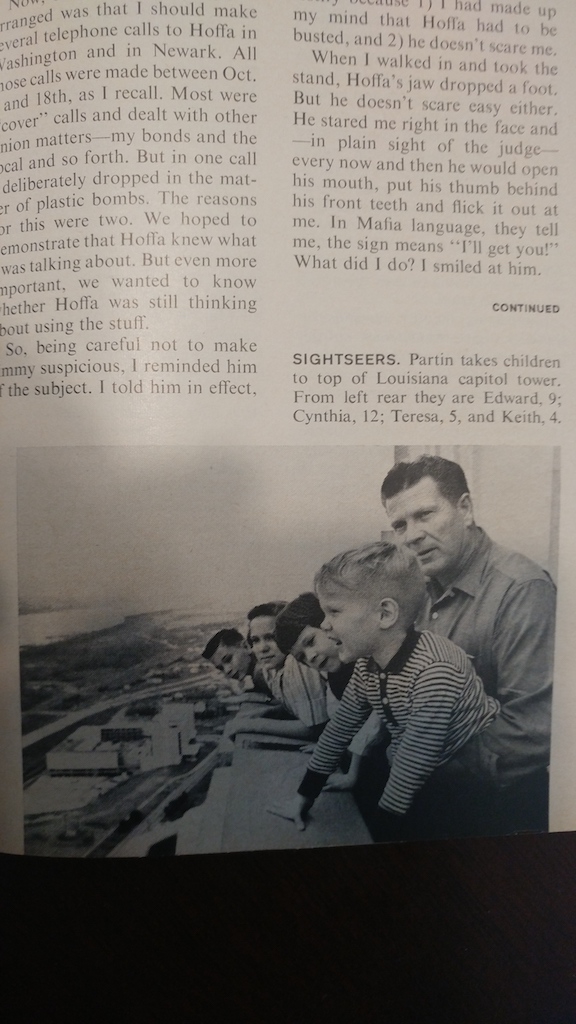

My grandfather had been the head of Teamster’s Local #5 since the 1950’s, thirty years total, and was probably the most famous person in Baton Rouge if not all of Louisiana. Most people I knew called him Big Daddy, but he known nationally as Edward Grady Partin, the big, rugged, handsome Teamster leader who was in a Baton Rouge jail on kidnapping and manslaughter charges when U.S. Attorney General Bobby Kennedy and FBI director J. Edgar Hoover freed him infiltrate the Teamster’s inner circle and find something – anything at all – to remove International Teamster president Jimmy Hoffa from power; kidnapping two young children was the “minor domestic problem” Hoffa would quip about for the remaining 11 years of his life. All of Baton Rouge relished the Life magazine spotlight on the Partins shared with newly appointed President Johnson’s family, especially the photo of Big Daddy with his five children atop the state capital building, smiling and holding my dad in his arms. My dad and I looked so so much alike that many people confused us, especially because we were only 17 years apart in age. He was my dad, and ever since I was a toddler calling my grandfather Big Daddy made sense.

Big Daddy’s 1964 testimony and Bobby and Hoover’s phrasing of his task reached the supreme court and was followed nationally, not just because it was Hoffa but also because the case was overseen by Chief Justice Earl Warren, internationally famous for the 1964 Warren Report that mistakenly said Lee Harvey Oswald, a New Orleans native who trained in the Baton Rouge civil air force under the alias Harvey Lee, acted alone when he shot and killed President Kennedy in 1963; and that Jack Ruby, a Dallas night club owner and gopher for Hoffa and the mafia, acted alone when he shot and killed Oswald 48 hours later. To protect their star witness from deformation by Hoffa’s army of lawyers, Bobby, the president’s little brother who was thrust into power solely to get Hoffa, and Hoover, a man in power so long he had seen two presidents assassinated, showcased the Partin family across national media, plastering photos of Big Daddy shirtless in his boxing shorts and gloves, strapped to a lie detector, and posing with my dad, Uncle Keith, and aunts Janice, Cynthia, and Theresa as a smiling family perched atop the state capital, happier than pigs on a small Iowa farm. For a few years, the Partin family was famous nationally, maybe even internationally.

Bobby said that Big Daddy was an “all-American hero” for risking his life and the lives of his family to clean up corrupt unions and stand up against Hoffa’s mafia colleagues, men like New Orleans boss Carlos Marcello. Life magazine, whose editor was a buddy of Bobby, dedicated issues to Big Daddy and the Partin family and shared with the new first-family, the Johnsons, after vice-president Johnson assumed presidency. The moniker stuck, and Big Daddy’s prestige grew in Baton Rouge because he could defy America’s most powerful man, the mafia, and the constitution of the United States with impunity.

Big Daddy returned to Louisiana and continued to run the Louisiana Teamsters, and his picture made front page news in Louisiana every month or so. His name came up again nationally when Bobby Kennedy was assassinated in 1968 and Hoffa vanished in 1975, and as part of the almost monthly campaign against organized crime. In 1983’s film “Blood Feud,” people remembered what Big Daddy and Hoffa looked like, and the burly and handsome actor Brian Dennehy portrayed Big Daddy in one of his first major roles, the same year he portrayed the Korean war veteran and sheriff who pursued Sylvester Stallone in Rambo: First Blood, a film about a Special Forces Vietnam veteran with PTSD who shot up a small town with an M-60 after deputy sheriffs drew First Blood.

In Blood Feud, named for the years of intense public battles between Hoffa and Bobby, Robert Blake won an academy award for channeling Hoffa’s rage, Ernest Borgnine portrayed J. Edgar Hoover, and some daytime soap-opera heartthrob whose name I can’t recall portrayed Bobby. Big Daddy was our home-town hero and everyone talked about him more than anyone else in the film, and every time Brian Dennehy was in a new film Baton Rouge people were reminded of his role as Ed Partin.

Big Daddy ran the Louisiana Teamsters for thirty years, including when he was in his cushy minimum security prison with a color television in his room in the early 1980’s, just like Hoffa ran the International teamsters from behind federal bars where he pummeled mattresses eight hours a day for his prison work detail, writing his memoir about how Big Daddy and Bobby Kennedy put him there. From his prison room, Big Daddy said he would endorse governortorial candidate John Edwards, a four-time governor despite two-term limits because Edwards was impeached twice and didn’t complete two terms; Edwards refused the endorsement, saying my grandfather was too controversial, and boasting he was so popular that he’d win without the endorsement and the only way he’d loose was if he were caught in bed with “a live boy or a dead hooker.” Yet Big Daddy was too controversial for him.

In 1981, my equally huge but much less controversial great-uncle Doug Partin was elected president of the Teamsters in Big Daddy’s place, just like Hoffa was eventually replaced by his protege, Fitzgerald. Uncle Keith, my dad’s little brother and, like Doug, an inexplicably mellow gentle giant, was on deck to take Doug’s place. Keith and Doug looked identical, sharing Big Daddy’s sky blue eyes and strawberry blonde hair, which came from Grandma Foster’s family line and bore no resemblence to great-granddady Grady’s hazel eyes, and Keith missed the dark brown eyes from Mamma Jean that dominate the difference between me, my dad, Aunt Janice, and the blue-eyed Partins who made the news most often.

The Partins were a Louisiana legacy, and half of Baton Rouge had worked for Big Daddy at some point, driving trucks to ship Louisiana’s agriculture products across the country to ships in the ports of Baton Rouge and New Orleans to be sent up the Mississippi river or out the Gulf of Mexico and across the globe. The burgeoning petrochemical industry along Chemical Alley upriver of the capital building depended on Teamsters to ship gas and plastic pellets along the purpose-built I-110 that connected the chemical plants and Baton Rouge airport to the cross-country I-10 that spans from Florida to the Santa Monica pier, passing the port of New Orleans so Teamsters can drop off or load up oproducts that are on every shelf in every town and keep America’s economy afloat. And, like Hoffa funded Hollywood films, Big Daddy brought the movie industry to Louisiana, using Teamster trucks to haul equipment and Teamster trailers to house actors and workers, and to employ local people and get them to star in Hollywood films.

The 1988 film “Everybody’s All American,” an epic football tale spanning 25 years of a celebgrated football player’s life, staring Dennis Quaid, Jessica Lange, Timothy Hutton, and John Goodman, was filmed in Baton Rouge the winter two years before it was released, and in it you can see a handful of my classmates and some of my teachers as uncredited extras in a stadium of 10,000 Baton Rouge people dressed up in 1950’s garb; ironically, I was not in the film, because I was with my dad in Arkansas over Christmas, but if you squint at the screen, you can see Lea and a couple of wrestlers cheering in the stands when Dennis Quaid runs for a touchdown.

In one scene, a crowd gathered around the state capital was reshot because of a snowfall so rare in our warm southern city that, though surreal and magical, would have been too fantasatstic for a serious film set in the warm south, where people wore short sleeve football jerseys and rode around in convertibles even in autumn. But it was because of the rare snowfall that everyone in town talked about the first shooting and their small part in it, and Everybody’s All American was still daily chatter by the time I wrestled Hillary Clinton. The film’s name was an obvious shout-out to Big Daddy, who, because of Bobby and Look! and Life, many people mistakenly thought was an all-American hero.

I never talked about my Partin family. I was one of the few people who knew that Big Daddy was a rapist, murderer, thief, adulterer, lier, bearer of false witness, racketeer (I wasn’t sure what that meant, but I knew it could send you to prison), embezzler, drug addict, betrayer of teammates, collaborator with Fidel Castro, and a man who, according to Mamma Jean, alerted her to his lifestyle when he stopped going to church on Sundays. She was a woman who could quote the bible and the U.S. Constitution, especially the 5th Amendment and Warren’s Miranda Rights that remind us we have the right to remain silent, a right few people practice with her diligence.

It was because of Big Daddy that I asked to be assigned to the 82nd Airborne, my ultimate test of nature versus nurture. The 82nd sported an patch on their left shoulder with two A’s under an Airborne tab that stand for the All Americans, a name given to them when they were created as the 82nd Infantry to fight what was called The Great War before we began calling it World War I. The Great War began only a generation after the civil war, where brother fought brother, and someone noticed that the 82nd was the first time in American history that a military unit had soldiers from every one of the United States, and the army assigned the moniker All Americans to the 82nd in an effort to inspire unity among former enemies. When Hitler began using paratroopers in WWII, the 82nd became America’s first paratroop’ unit, the forefathers of our special forces, and the Airborne tab was added above the AA on our shoulders.

The All Americans were as famous as Big Daddy was when I was a kid. The Christmas and New Year of 1989-1999, when I was already signed up for them and training to wrestle Hillary Clinton, they were on the news every day after President Bush Senior sent them to Panama as a continuation of Reagan’s war on drugs. They flew there overnight in a fleet of C-130’s, nicknamed the Hercules, and C-141 Starlifters skimmed over the jungle trees at 4am, then piled out of the side doors and filed the air with parachutes, machine guns, and testosterone. They overtook Panama within a few hours, and surrounded President Noriega’s compound until other American forces joined.

Over Christmas and New Years, I skipped rope and cut weight and watched international news follow the 82nd and two platoons of .50 cal machine gunners from the 504th anti-armor company, and show them holding Noriega captive by surrounding his compound for weeks. To capture him alive, guys I’d grow to know well brought in speakers big enough to host a music festival and blared heavy metal 24 hours a day, depriving Noriega and his personal guard of sleep with songs taken from Van Halen’s 1985 album played all day and night for weeks, songs that so ironic that not even Hollywood could contrive the scene, like “Jump!” and “Panama.” I suspect Noriega is the only person other than David Lee Roth who knows the lyrics to Panama better than I do.

The news was so detailed that we noticed no 82nd paratroopers died, yet a handful of the then newly-known Navy SEALS did, and so did two Delta Force anti-terrorism commandos, a team we suspected existed after Chuck Norris’s cheesy 1986 film, “The Delta Force,” the first in an equally cheesy three-part franchise based, in part, on the 1985 hijacking of TWA Flight 847 and the 1979-1980 Iran Hostage crisis where 53 Americans were held aboard an airplane for 444 days, part of the reason Carter lost to Reagan in 1980, in addition to the resulting oil crisis that led Teamsters to lining up for miles to fill their rigs.

The 82nd was the president’s quick-reaction force: 12,000 paratroopers on call to deploy anywhere in the world within two hours without congressional approval for up to thirty days. Before Panama, the 82nd was on the news for Grenada in 1985, the Dominican Republic in 1983, and Honduras in 1979; before that, they were one of many units in Vietnam for more than a decade. In WWII, the 82nd was known for five combat jumps behind enemy lines in Europe that turned the tides of war, and celebrated by actors as big as John Wayne, a little guy Big Daddy knew from when the actor filmed civil war movies around Louisiana and Mississippi’s plantations, shown wearing their maroon berets, coincidentally the color of the Capital Lions singlets. But, what stuck in my mind more than the maroon beret was their nickname, The All Americans, and the sarcastic taunt Jimmy Hoffa used about Big Daddy in news and in his autobiography. I wanted to test nature versus nature by becoming a real All American, not an actor playing one or a false god worshiped as one.

On 16 March 1990, two weeks after Hillary Clinton broke my finger, I rode a Honda Ascot 500cc shaft-drive motorcycle to my grandfather’s funeral, a small and low-maintenance machine that a teammate lent me and that got around 55 miles per gallon and let me take trips to New Orleans, where I performed card tricks near Jackson Square for tips, modifying my methods to accommodate my broken left finger. My two left middle fingers were buddy-taped; for the funeral, I applied two fresh strips of bright white cloth tape, not because the fingers still needed it, but because I liked the way it looked and how it made me feel, and I hoped someone would ask about it so I could tell them about wrestling and what I was doing after I graduated high school.

I was wearing a white helmet airbrushed with blue letters that said “c/o 1990?,” a jab at overzealous seniors who wore shirts that said, “Class of 1990!” and a form of psuedo-apathy about my abysmal grades from 9th and 10th grade that made my graduation uncertain; had it not been for Coach asking me to try my best in academics, I probably would have had to attend summer school and forfeit my army contract, but I would graduate with a 1.87/4.00 GPA and make the requirement by 0.37 points; my senior GPA was a respectable 3.20/4.00, and I was proud of that.

I sported my cherished but gaudy fuzzy orange letterman jacket with blue sleeves a big blue letter B on the left chest, and I had meticulously adorned the orange fluff over my heart with 36 small gold safety pins, grouped in clusters of five for easy counting. The letter B had an admittedly awkward looking wrestling letterman pin, the one modeled after an old Greco Roman statue with one man down and the other grasping him from behind. For cross-country track, I had Mercury’s winged feet; for chess, a rook; and for theater, the comedy and tragedy faces of theater. Though I swam for practice, catching a ride to Catholic High’s pool, I was an abysmal swimmer who sank like a rock and didn’t letter.

Across the back of my jacket was a sprawling black-colored “Magik” that I had splurged on and had embroidered at a t-shirt and nick-knack shop on Florida Boulevard in a run down strip mall walking distance from Belaire, nicknamed Little Saignon because of the flood of Vietnamese who moved there after Saigon fell in 1975; like southern Louisiana, southern Vietnam was a humid, muggy agricultural and seafood region that the French had colonized and spread foods like French baguettes and pate, so the muggy port town of Baton Rouge – Red Stick in French – was a logical move for thousands of Vietnamese who had supported America and had to flee the communist takeover. They advertised their bon-migh sandwhiches as “Vietnamese Po’Boys.”

To blend in, and after a few of their kids dressed as GI Joe for Halloween trick-or-treating were shot by Vietnam veterans living in Belaire’s cheap apartments, the Vietnamese-owned businesses in strip malls along Florida Boulevard began selling heavy metal patches and veteran shirts with Airborne wings and berets that said things like “Death from Above” and “Kill ’em all, let God sort ’em out,” and not checking ID’s when selling cigarettes and cheep beer. I never drank alcohol, a trait I picked up from Big Daddy, who said it loosened lips. But Lea and I often hung out at the heavy metal t-shirt shop that also sold glass tobacco pipes and ornate desk lamps that most kids knew were bongs, and I dropped quarters into a few stand-up video games they kept near the cigarette machine. Below my black embroidered nickname was a hand-sized black and white skull wearing what looked like a magicians hat, but was actually a character of Slash, the guitarist for a new band called Guns and Roses, who wore a top hat he stole from a Los Angeles thrift store wherever he went and that became his signature look on M-TV.

I spent all of my money on Pac-Man and Galaga, the embroidery and Guns-N-Roses patch, and a Vietnamese Po’Boy to celebrate not cutting weight for a while, so I didn’t have enough to pay the tailor to add the skull and top-hat. Lea lent me a sewing kit, and I painstakingly hand-sewed the patch under my nickname. The patch was prophetic, and I’d learn that – though not known by news crews – when the side doors of my future team’s C-141 Starlifter opened and the hot muggy air whooshed inside, someone slipped the Guns-N-Roses “Appetite for Destruction” cassette into the speaker system and blared Slash’s quintessential guitar riff; for the first time, 123 paratroopers on a one-way trip heard Axl Rose’s wailing voice scream “Welcome to the Jungle.” Sometimes, real life is more fantastic than fiction.

I slowed the motorcycle down and rode along the shoulder of Airline Highway, the small engine barely audible over the traffic jam of cars and idling 18 wheel trucks headed towards Greenwood Funeral Home. I slowly braked onto the grass beside a paved parking spot and as close as police would allow, turned off the bike, and draped my helmet on the handlebars and my jacket on the seat. There was a slight rumble from idling 18 wheelers on Airline, and a breeze that smelled of springtime azaleas made the pins on my jacket tinkle like tiny wind chimes. My face shone from lingering pride at media coverage and a small award from Coach and the team that they presented in front of all 383 Belaire seniors. Most athletic. Coach’s award. A few others. We had just lost three of our elected senior representatives to a drunk driving accident when they were thrown from the back of an open pickup truck and split their heads open on Florida Boulevard, so everyone was emotional and teachers wanted to focus on something positive; my using a helmet despite Louisiana’s lax laws was mentioned. So many kids applauded my brief moment on stage that I was still riding the high, and after all of that attention I was unimpressed by the crowds of people and reporters clustered outside of the funeral home.

I strolled past the rows of police and federal marshals dressed like Men In Black wannabes, a lingering effect of men loyal to Hoover’s archaic dress code, and I walked up to Aunt Janice. She bent down to hug me, and we went inside.

Besides Grandma Foster, Big Daddy’s mother and the only other tiny person in our family, there were twenty or thirty Partins, mostly from Big Daddy’s marriage after Mamma Jean, who stayed nearby at her sister’s house and was waiting for us to join later. There must of been two hundred people I didn’t know, but there were a handful I either knew or recognized. The former Baton Rouge mayor was there, and so was the entire Baton Rouge police department, reporters from every major newspaper, a hell of a lot of huge Teamsters, a gaggle of FBI agents, and Walter Sheridan, former director of the FBI’s Get Hoffa task force and a respected NBC news correspondent, and a surprisingly long lineup of aging brutes from the 1954 LSU football national champion team who had served as Big Daddy’s entourage.

Billy Cannon, a veteran of the 1954 team and LSU’s first Heismann Trophy winner, was there. He was a two time All American, former pro for the Houston Oilers, and the biggest celebrity on the biggest float in the Spanish Town Mardi Gras parade. Growing up, I saw Billy’s handsome smiling face was on billboards all along I-110, between downtown and his home in Saint Francisville, his bright white smile advertising his dental business on their way to and from work in the chemical plants north of downtown. When Hollywood filmed Everybody’s All American, people in Baton Rouge felt it was a movie about Billy; the fictitious film was based on a Sports Illustrated writer’s book of the same name who would have remembered Billy, so there’s probably some truth to that, and part of the reason they set the film in Baton Rouge. Of course Billy would be Big Daddy’s pallbearer; it made Big Daddy seem bigger than life, even after death.

After everyone finished speaking, Billy, Doug, Kieth, and three other Teamster brutes heaved to pick up Big Daddy’s casket and carry it past all the reporters to be laid in Greenwood cemetery. With all of those celebrities at the funeral home, it’s no wonder no one asked about my letterman jacket or buddy-tapped fingers, not even the reporters and television crews supposedly focusing on things like that. The New York Times simply listed me as one Edward Grady Partin Senior’s grandchildren; they mistakenly said “and great-grandchildren,” but I was the second oldest and knew all of my cousins from both Big Daddy’s marriages, proving that even the NY Times makes mistakes, just like Life magazine and The Warren Report.

Only Walter asked about my fingers. Most people wouldn’t recognize him; he had a small role in “Blood Feud,” too, as the head of the FBI’s Get Hoffa task force, but it was uncredited and no one knew what he looked like, anyway. Hoover oversaw around 6,300 FBI agents, and at one point 500 of them were under Walter with only one goal: Get Hoffa. They were, until America’s efforts to get President Noriega and Osama Bin Laden, the most expensive and extravagantly resourced American effort against an individual.

Walter was, in my mind, team captain of the Get Hoffa Task Force. Hoover was his coach. Bobby Kennedy, whom I didn’t understand yet, hand-picked Walter to rejoin the force and get Hoffa.2 Yet he was a humble man, and he didn’t take credit for his role in finally ending the pursuit. He was known to be truthful and diligent, which is probably why NBC sought him to cover the New Orleans trials against men charged in President Kennedy’s murder in New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison’s rally against what many people believed – and still believe – was a conspiracy involving senior members of the CIA and FBI.

I barely knew Walter, but he was a friend – of sorts – of Mamma Jean and Grandma Foster, and for all of the 1990 wrestling season he kept checking with Aunt Janice and asking what Big Daddy had been saying. He seemed interested in anything a Partin said or did, and I told him I broke my finger wrestling in city finals. I didn’t use Hillary’s name, because I didn’t know yet how funny it would sound if I said Hillary Clinton broke it; I spent a lot of summers and holidays with my dad in Arkansas, but I wouldn’t know that Bill Clinton was governor and that his wife was named Hillary for another two years. Walter congratulated me and seemed interested in whatever I had to say, and I talked his ear off about how I was headed to the 82nd.

The mayor and the football players said a lot of words, and so did a few of my younger cousins. Tiffany, Janice’s daughter and the only cousin older than I was, spoke. She was 18, almost six feet tall, and, like my dad, Janice, and me, had Mamma Jean’s dark brown eyes instead of Big Daddy and Grandma Foster’s sky blue eyes. Tiffany was gorgeous, like Mamma Jean and Janice, and had been homecoming queen in a Houston high school. She and all of my aunts and most of my cousins lived near the house Bobby bought for Mamma Jean in exchange for her silence. Tiffany was a remarkable public speaker, and she held the hundred or so people listening captive. She told stories about Big Daddy’s sweet smile and dotting affection for his family, and everyone was already in tears when Jennifer took her turn.

Jennifer was Cynthia’s oldest daughter and a high school sophomore in high school, but she was still taller than I was. Jennifer had written a letter preparing for the funeral in January, when we knew Big Daddy only had months or weeks left to live. She read it in front of everyone and put it in Big Daddy’s pocket before they closed the casket. Aunt Cynthia would send a copy to Doug after the funeral, scribbling a note to explain it and saying:

Uncle Doug,

Jennifer, my daughter, wrote this in school almost 2 months ago. She put it in Daddy’s pocket, along with Janice’s letter.

In his autobiography, Doug photocopied Jennifer’s hand-written letter, which said:

I never really knew my grandfather. His whole life is a mystery to me. For he ended up being a bother to Hoffa and a good friend to Kennedy. The only way I learned about his part was from reading Life magazine and books. Now time is flying by so very fast, and I am afraid I will never look at his tender and loving eyes again. For he is extremely ill and near death. Lord, when he dies, his new life will begin. So give him mercy, for he tried his best. I know he’ll go to the heavens above and look down upon me and feel my love.

To Big Daddy from your loving granddaughter,

Jennifer

January 1990.

Jennifer sobbed as she read her letter, and when she finished everyone was bawling; not even I wanted to point out the understatement of being a “bother” to Hoffa, nor did I want to tell my cousins that the Big Daddy they knew from Life magazine and books wasn’t the one I knew from growing up with him in Baton Rouge rather than with our close-lipped Mamma Jean in Houston. She and Tiffany were the only two of about a dozen of my cousins to speak. I did not because no one asked me to, and neither did my cousin, also named Jason Partin, a football star for the Zachary Broncos who was younger than I was but already over six feet and around 190 pounds; his father, Joe, was Zachary’s football coach and principal, the only Partin not a Teamster. Jason and Joe had a mumbly southern accent like I did back then, and we lacked Big Daddy’s charming drawl or our female cousin’s soft appeal, which may be why none of us were asked to speak.3

After the funeral, when most people got up and flocked around Billy and the aging Tigers, I leaned over and told Walter – who didn’t seem to care about football – that I had joined the 82nd. He smiled, but didn’t pry. I then told him what Edward Partin’s final words were, and I chuckled as I said it: “No one will ever know my part in history.” He agreed that it sounded funny when said out loud, and that my grandfather was probably right.

Not satisfied, I added, “He taught me how to throw a punch.”

Walter was unfazed.

“It’s all about your stance,” I said. “And long arms – it lets you surprise someone.”

Walter said nothing, but he had a kind smile and I continued.

“And stay calm,” I said, holding up the lanky knobby forefinger on my right, untaped hand. “Pay attention to your heartbeat.” I lowered my finger and said, “That’s how he beat the lie detector.”

I smiled, letting Walter know I knew that secret. Hoover, when he was Walter’s boss, had put a photo of Big Daddy, strapped to a lie detector machine and surrounded by federal scientists in white lab coats, in Life Magazine. They showed the squiggly lines of his results, and Hoover said that was proof that a year before President John F. Kennedy was shot and killed, Jimmy Hoffa had plotted with Big Daddy to kill his little brother, U.S. Attorney General Bobby Kennedy by obtaining military C4 plastic explosives from New Orleans mafia boss Carlos Marcello, who would probably get them from Fidel Castro, and blowing up Bobby’s house with Bobby and his wife and children inside; that scene was so well known by then that it was a key part of 1983’s film “Blood Feud,” emphasizing how Big Daddy risked his and his family’s life to come forward against Hoffa. But we all knew Big Daddy could fool any lie detector test by remaining calm and practicing whatever he wanted to say so that no machine could detect the little hiccups between feelings and thoughts and words, like how a wrestler practices a move until it’s a habit. Walter smiled back, and I knew I was ready for whatever the 82nd could throw at me.

I left Louisiana two months later and began basic training in Fort Benning, Georgia, home of the U.S. infantry and Airborne schools.

On 03 August 1990, Saddam Hussein ordered his army of 400,000 soldiers and all of their tanks, the world’s largest fleet at that time, larger even than America’s, to overtake the small country of Kuwait. They rolled across the border and succeeded as quickly as America had overtaken Panama only six months before, then turned their turrets towards Saudi Arabia, brining in SCUD missiles and the chemical weapons Saddam had already used on his enemies in Iraq’s internal wars; if there were a tournament of terrifying ways to die, serin nerve agent would win at least a silver medal.

President Bush Senior called the 82nd Airborne. Two hours later, Defense Ready Force 1, the first of nine 82nd Airborne battalions and the one on two-hour recall that month, boarded a few C-141’s en route to Saudi Arabia. 18 hours later, a handful of young paratroopers armed with puny M-16, M-60, and M243 machine guns, a handful of M-203 grenade launchers (the MK-19 grenade-launching machine gun with armor-piercing rounds wouldn’t be delivered for another few months), about ten .50 cals, five TOW anti-tank missile systems capable of punching through 38 inches of armored steel, and a handful of the newly issued and contentious 9mm Berretta sidearms that had replaced the trusty .45’s that had “won two world wars,” not like the televised debacle only two years before, where an army of police officers and FBI agents armed with 9mm’s squatted behind their cars and shot what seemed like hundreds of rounds yet were still outgunned by two bank robbers wearing body armor and calmly standing in the middle of a street in Miami. But the 82nd would fare much better. Those few plane fulls of young men faced off against half a million Iraqi soldiers and dozens of thousands of Soviet T54 and T55 tanks. President Bush said they drew a line in the sand that no one dared cross.