Stretch Armstrong and My Dad

About a month or two after I leave the hospital, when I no longer wear a turban and most of my hair has grown back, I’m sitting on my couch and watching Saturday afternoon television with Craig Black. He jokes that we live in a Black and White household. I think he’s talking about the television and I say yeah, it’s a black and white house, not like the big color TV at the hospital.1 When The Lone Ranger is over and before boring news begins, I get up and walk to the kitchen.

Linda is standing in front of the stove. She adds milk to the pot of mac and soon-to-be cheese, pours in the packet of orange powder, and stirs with a wooden spoon. PawPaw calls out from the bathroom, where he sometimes sat on the porcelain throne, waiting for a poop, and perhaps finding the only spot in our tiny home where he could repose quietly. Linda sets down the spoon, picks up PawPaw’s pack of Camels from the cluttered kitchen table, lights one, takes a short drag to flame the tip, and hands it to me. The smoke curls up and reaches into nostrils, and I almost gag. It’s not like wood smoke, it’s more like smoke from when PawPaw pours diesel on a fire-ant mound, sharp and harsh and biting. I move the cigarette away from my face, holding it upright, pinched between my right thumb and forefinger just above the little printed camel. My other fingers are stuck out, making my hand look like a sideways okay sign that’s holding a smoldering twig. I’m barely pinching it above the little blue printed camel, careful to avoid crumpling the soft paper that lacks a filter. But not too loosely, because I don’t want to drop it and add more burn marks to the pot-marked linoleum. I walk across the kitchen towards the bathroom, as focused as a juggler crossing the stage with plates spinning atop tall poles.

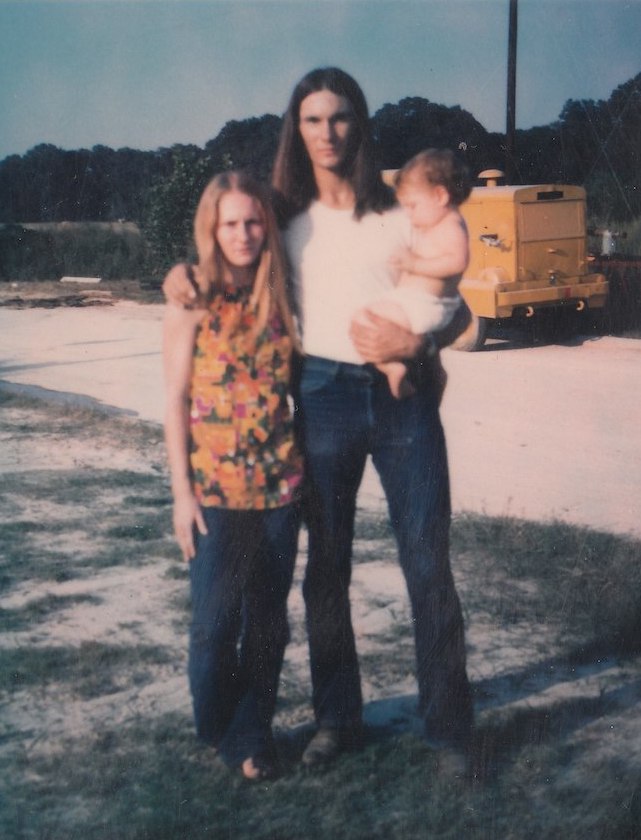

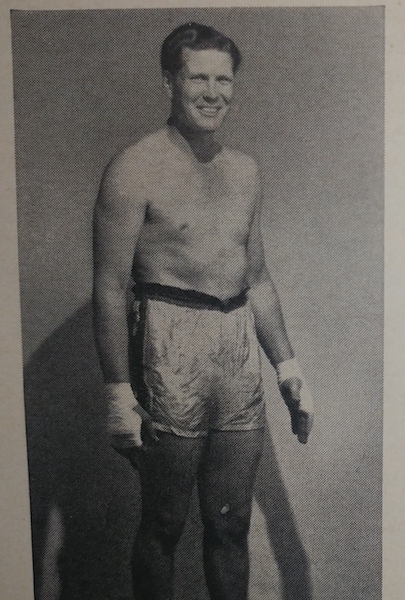

I stop in front of the big hallway mirror with the Camel smoking in my right hand like a steam pipe on a train engine, and I peer at my hair. The bandage has been off for a couple of weeks, and my hair has grown back to a fuzzy ball that makes my head look like a maroon colored chia pet. I drag my left hand across the top. It’s soft and tickles my palm, and it pops back up when my hand moves away, just like the tall weeds I brush when walking along Foster Road with PawPaw. I hold the cigarette motionless and slightly above my nose level so that the smoke doesn’t bother me. I stare at myself staring at myself holding the cigarette. I’m a handsome kid, I think, like MawMaw and Debbie say I am. My dad says I’m grown up enough to make my own decisions. He’s handsome – at least, that’s what I’ve heard some of the women at Brian the one handed drug dealer’s house say – and everyone says I look just like him, so it’s confirmed: I must be handsome, too. I also think I look grown up holding a cigarette, especially with a big scar like my dad’s leg scar. I twist my head again but still can’t twist and stretch enough to see my scar, but I know it’s there. I stare back at myself, and without knowing why, I rotate my wrist and take a drag from the Camel. Instantly, I’m coughing and hacking and almost drop the cigarette onto the pot-marked linoleum, but I hold on tightly – though not too tightly – and focus on not dropping it while I cough and cough and cover my mouth with my free hand.

“D’at you, Lil’ Buddy?” PawPaw calls out from his throne. His voice is all-knowing, mischievous, and playful. There’s no fooling PawPaw: he knew what I had done.

I’m coughing and can’t answer. I turn around and push open the door and hold out the cigarette for him to take from his seat on the throne. He chuckles and takes it and reminds me that cigarettes are only for grown ups, and I have a ways to go. I walk back to the kitchen, wanting some milk to wash away the scratching in my throat. Linda says something about me learning a lesson, pours milk, and goes back to her and Craig’s bedroom. MawMaw comes out and chases me and gives me some shugga’ and a plate of cookies and a small glass of milk with some cartoon character on it that I don’t recall. She scoots me to the table to play with my train. I see her turn and take up Linda’s job of stirring the mac and cheese, and I hope we have fish sticks with dinner, piled with ketchup the color of my hair. I put on my Lone Ranger cowboy hat and move my trains around for a while, making little train noises like the mouse with a motorcycle made to move his motorcycle; in my mind, I’m a little conductor and the train is moving to the beat of my rumble. When PawPaw’s out of the bathroom, I go in and wipe off my milk mustache and the red shugga mark that MawMaw had snuck in and smacked on my cheek.

I walk out and hear the sound of gravel crunching. A rumbling truck engine turns off. MawMaw steps away from the stove and turns to the carport door. She parts the drapes blocking the small window on the top half, and frowns.

“Hmmph!” She mutters. “Ed, she says in her loud serious voice, you better come in here.”

She steps towards me on the far side of the cluttered kitchen table and wraps an arm around my shoulders. A fist pounds on the door; it seems to buckle inward with each rap, and the window panes rattle like when a jet airplane passes over. PawPaw opens the door and immediately says: It ain’t your day, Ed.

“I don’t care what day it is!” My dad’s voice booms. Like PawPaw’s truck, his reaches into your chest and clenches your lungs and makes you pay attention.

“Ed, please,” PawPaw says in his serious voice. “Next week. You know d’ rules.”

“Goddamnit, he’s my son, and I’ll see him whenever I want!” He pokes his head inside from a spot by the window above PawPaw’s head and gets eye contact with me, and sticks arm arm through. It’s holding one of the fancy paper bags with a rope handle from Cortana Mall. He says in a softer voice, “Hey Justin – goddamnit, I mean Jason – I brought you something. Do you want to see it?”

PawPaw sees me looking at my dad with anticipation, and he steps aside without saying anything. MawMaw lifts her arm and I rush to my dad. He steps inside between PawPaw and me and kneels down and looks at the bag and smiles sheepishly. He says, “I think this is what you wanted.”

I peer in the bag, and it’s a Stretch Armstrong! I exclaim something and pull the unopened box out of the fancy bag. I see the green face and pointed ears and bald head, and instantly tell him it’s not Stretch. Stretch looks like Keith, with white skin and blonde hair and big muscles. This one’s Evil Stretch, the green villain with ears like Keebler elves; his ears were the giveaway, because though I had seen him green on the hospital’s big color TV, he was light black on our small box. It’s hard to hide those ears, no matter what color he was. Even though he’s Evil, I know he still stretches, so I’m happy and I fumble with the box, trying to open it. My dad says we can go to the mall next week and I can pick out what I want. I’m stoked! That means I’d have Stretch and Evil Stretch! He asks if I’d like that, and I exclaim yeah!

“Okay Ed,” PawPaw says. “Thank you for d’ gift, he says, but you know d’ rules. You gotta go.”

My dad stands up and towers over us and booms, “Fuck the rules!” He tells PawPaw again that he’s my father and can see me whenever he wants.

Please, Ed, PawPaw says. Next week.

MawMaw moves to his side. I keep fumbling with the box. Shouting doesn’t bother me. Calm at the helm of a ship, PawPaw would sometimes say of me whenever my dad and him spoke in serious voices. PawPaw says he tries to stay calm when a hurricane’s blowin’ over trees, that’s he’s waitin’ and watchin’ for things to settle down before stepping out to help, and he learned that from me. I wait, but I’m growing frustrated at my box despite trying to stay calm about it.

My dad steps towards PawPaw and pokes his finger down and says, “Look here, Ed. He’s my son. I don’t care what the fuck Judge Pugh said. He’s dead now. Fuckin’ idiot shoulda never did what he did. Justin’s my son, and I’ll see him whenever I want!”

He pokes his finger into PawPaw’s chest to emphasize that he does whatever he wants whenever he wants, and PawPaw stumbles backwards. He catches himself against the counter where we eat breatkfast, rights himself, and says, “Ed, you got to go.” My dad stands his ground, narrowing his eyebrows and shooting lasers of will power at PawPaw.

MawMaw moves by my side and puts her arm around me again. I’m focused on that box and about to loose my cool. I wish had a knife.

My dad booms some explicatives that I don’t recall, and Linda and Craig walk into the kitchen and stand between MawMaw and PawPaw. Craig’s almost as tall as my dad, but so thin he seems smaller than PawPaw. Linda tells my dad to leave. My dad inflates his chest and stands tall. Craig has his stoned eyes and stares at my dad but says nothing. My dad brushes Craig aside as if he were a blade of grass blocking a path, and reaches down and grabs my right arm and yanks me closer; but MawMaw clings to my other arm and I jerk to a halt. My dad pulls again, and Evil Stretch and I are lifted in the air between MawMaw and my dad. I’m taller than PawPaw now. My dad’s hand is a vice grip on my upper right arm, the one cradling the box, and MawMaw’s two hands are wrapped around my left wrist. I’m stretched between them like two kids stretching Stretch Armstrong on TV.

Linda lurches to MawMaw’s side and grasps my forearm and I feel a stab of pain. I break my calm and cry out, but no one seems to hear. Everyone except Craig is shouting something. PawPaw steps towards my dad, and my dad shoves PawPaw with his free hand. PawPaw flies backwards, and Linda lets go of my arm and leaps onto my dad. My dad shoves her away. PawPaw lurches between Linda and my dad, and says in the loudest voice I would ever hear him use that he’ll call the police again. My dad shouts something so loud that my chests clutches my lungs and I can’t breath; that shout must have woken up the baby, and her shrill cry echoes through the kitchen and drown out even my dad’s shouts.

Linda rushes towards the bedroom. Craig strolls after her. The kitchen is quiet except for the baby’s crying and my sobbing and PawPaw’s panting. He takes my arm from MawMaw and holds my hand. My dad lets go of my arm. Everyone stand there for a few moments. The baby stops crying.

“Let me say goodbye to him outside,” my dad says.

“Five minutes,” PawPaw says, breathing normally now. “Stay in d’ carport.”

I hold up my left arm and tell all of them that it’s bleeding. MawMaw says someone’s fingernails must have scratched it. She says she’ll get a Band-Aid and bring it out to me. My dad reaches down and I take his hand and stifle my sniffles; no one likes hearing a baby cry. We step into the carport and my dad picks me up and sets me down on the hood of MawMaw’s car. PawPaw closes the door but keeps it cracked with a peeking-sized gap. The crickets are chirping, unfazed by the commotion. Calm in the storm. I still have the box with Evil Stretch. My dad kneels down and his eyes are just barely below my nose. His long straight black hair is matted. He smells like swamp and pot. He looks up at me with our dark brown eyes and smiles.

“You know I love you, son? Right?”

“Yes.”

“Do you love me?”

“Yes.”

His smile widens and his eyes soften. He whips out his big Buck folding knife and effortlessly slice open the box and pulls out Evil Stretch. I pull him out and instantly try to stretch him. I can’t. My dad takes him and stretches him farther than I had been stretched a few moments before, and says that one day I’ll be big and strong, just like him.

MawMaw steps out with a Band-Aid and we fret over getting it just right. I like wearing bandages, because people see them and tell me how brave I am. I was an expert on bandages by then, and I knew which angles stayed on the best. We get it just right. MawMaw says I’m brave or strong or calm or something like that, and I beam. She walks back inside and leaves the door open a bit wider; I can see the kitchen counter now. I hear her and PawPaw talking, but can’t make out the words. My dad tells me next week we’ll go to the mall and get whatever I want. I say something about Stretch Armstrong and ice cream and the horse merry-go-round, and he says of course, I’m his son, and he loves me.

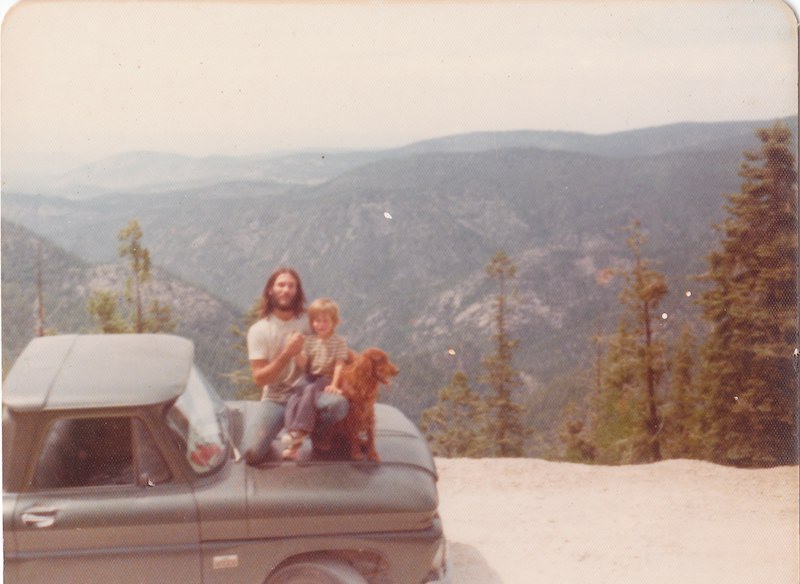

MawMaw comes out with a plate of cookies and tells my dad he can take one to go. PawPaw is standing in the doorway, a few inches taller because of the step up, but still tiny compared to my dad. My dad takes a cookie and asks if he can show me his dog in the truck. PawPaw says yes, and he and MawMaw wait by the door and I take my dad’s hand and carry Evil Stretch to his truck. He opens the passenger door and a big red dog the color of ketchup leaps out and wiggles and runs around us. He tells her to sit and tells me her name is Anne. She’s an Irish Setter. She’s our dog now. She’s sitting and her nose is at my face, and she licks me and I fall in love. He says he has to go, but says I can play with Anne when he picks me up next week. I think that sounds like the best day ever. He lifts her into his truck, hugs me goodbye, and tells me he loves me. I say I love him, too. I run back to MawMaw and the plate of cookies, wave goodbye, and we step inside.

Later that evening, after mac and cheese and fish sticks with lots of ketchup, I sit at the table and try to stretch Evil Stretch. I can’t, no matter how many times I try. I grow irritated, frustrated, or some other word I don’t know yet. I point my finger at his face and tell him I’m bigger and stronger than he is. He says nothing; that makes me feel more irritated. What good is a Stretch if it doesn’t stretch? It’s his fault, I tell him. He remains silent, goading me with his pointy ears and evil stare. I pick up one of PawPaw’s flathead screwdrivers. It’s as big in my hand as Big Daddy’s knife is in his, bigger looking than my dad’s folding Buck, if only apparently so because of scale in my hand.

I put it to Evil Stretch’s rib cage, rotating my wrist so the flathead is sideways, so that I can pierce between rib bones and not bounce off like an amateur who doesn’t know any better; I don’t know how I know that, and it’s not the exact words in my mind, but I recall rotating my wrist and I think I had overheard something about the ribs protecting the heart and lungs. I knew I should aim for either, like shooting a deer or elk in that area so they either die instantly or soon bleed to death. I knew a thing or two about almost bleeding to death, I thought, and I was bigger and stronger than Evil Stretch and would make him bleed to death. I thrust the screwdriver into his side, right where the soldier’s spear pierced Jesus, and the rubber resisted and I had to lean in and push harder. His skin gave away and the screwdriver slid deep and I relaxed, satisfied, happy to be the stronger one of us. I pulled out the screwdriver and Evil Stretch’s wound dripped a snot-colored milky goo that clung to the tip of the screwdriver without forming drops. I was mesmerized, having forgotten that I intended him to bleed and curious what the bloody goo was. I squeeze, and Evil Stretch’s wound pours goo. It drips down his side, and a few drops spill on the table by my train set. I feel differently, no longer irritated or frustrated, but scared or worried that I had broken my toy. I was back to reality, and my new toy was leaking. I had to save it. I set the screwdriver back down and tried to push the goo back in, like the doctors had done to my brain and blood, but the more I tried to force the goo into the gash with my right hand, the more my left hand squeezed and the more came out. I wasn’t thinking like I had with the cigarette. I become more and more agitated, rushing to push goo back in but squeezing more and more out. Despite not wanting to sound like a baby, I begin to cry.

I hear PawPaw behind me say, “What wrong, Lil’ Buddy?”

Between sniffles, I tell him that I stabbed Evil Stretch, and now he’s bleeding to death.

PawPaw picks up Evil and inspects his wound. He tells me we’ll be like doctors. Before we put the blood back in, we have to get him to stop bleeding. PawPaw cradles him gently. I see my finger dents in his body, because he’s unable to rebound like he had only minutes before. PawPaw wipes off the goo and applies superglue to the cut, but the glue doesn’t hold. PawPaw’s hand carefully holds Evil horizontally, without squeezing him, and we step over to the refrigerator and PawPaw opens the top freezer, moves things around, and rests Stretch on a flat spot. He says something about the cold making the goo flow less. He shuts the door and we chat about things I don’t recall while he smokes a Camel. I’m so upset I don’t want any cookies, and after a second cigarette we finally open the freezer. PawPaw was right, the goo wasn’t flowing any more. We try super glue again, but it fails again. We try to make a bandage out of duct tape, but it won’t stick, either. I’m distraught, but PawPaw says something about waiting and seeing, and we put Stretch back in the freezer and plan to check on him in the morning.

Super glue and duct tape didn’t work the next morning, and PawPaw says it’s time to say goodbye. We take him to the trash can by the cricket cage and PawPaw pushes a box over for me to stand on. I hold Evil Stretch on my open palms, like PawPaw had, and say a few words. I say I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to hurt him. I say he wasn’t really evil, that I just called him that. I look at PawPaw and he nods, then I drop Stretch into the trash and step down. PawPaw tells me I’m the nicest Lil’ Buddy in the world, and we go back inside.

Go to the Table of Contents

Footnotes:

- Craig Black made that joke often, even 40 years later when he retired as the landscaper and resident artist of Houmas Plantation in Burnside, a small town along the river road between Baton Rouge and New Orleans. The Baton Rouge advocate ran a feature story about him and his art, which focused on elves in forests scenes, but set in the swamps of southern Louisiana and with elves that had a hint of PawPaw twinkling in their eyes. He pointed to the big oak tree PawPaw had planted when Craig was a boy, and said that a family may enjoy his art in their living room, but a hundred thousand people a year found relief from the heat or enjoyed a picnic lunch in it’s shade, and that was a deep type of art that he learned growing up in a Black and White household. A year after he retired, when I was calling people and verifying or rejecting my versions of events, he agreed with my recollection of the time around my head scar, with the qualifier that he was usually stoned and prone to mistaken memories in the 70’s. ↩︎