PawPaw and The Scar

My first vivid memory centers around the eight inch scar arching across the back of my scalp. It’s the spring of 1976, when Baton Rouge azeleas were in bloom and their scent drifted in through the open windows of my foster-father’s ramshackle two bedroom, one bath, ranch style home off of the coincidently named Foster Road, near the intersection of Plank Road, two miles east of the Baton Rouge airport and a mile west of Glen Oaks High School.1 I’m asleep on my makeshift bed on the living room couch, and the smell of PawPaw wakes me up.

“Hey d’er, Lil’ Buddy,” he says.

I open my eyes and see his smiling face. He’s squatting down to almost my eye level. I smile back. He says, “’Bout time you woke up.”

PawPaw was born in the pine forests near Woodville Mississippi, but he had adapted a southern Louisiana way of speaking reminiscent of the Cajun accent, and he omitted his “Th” sounds and used “D” instead, like the New Orleans Saints football chant, “Who D’at! Who D’at! Who D’at Talkin’ ‘Bout Beatin’ D’em Saints!” I know it’s a Saturday or Sunday, because PawPaw’s there telling me it’s ’bout time I woke up, and he’s wearing his tree climbing clothes. On weekdays, PawPaw’s at work so MawMaw wakes me up, and we play around the house or go walk around in the air conditioning of Cortana Mall. But on weekends, cartoons may be on or I may go climbing trees with PawPaw, and they always begin with the smell of PawPaw’s aftershave.

I hop off the couch wearing my bedtime underpants. I’m already moving into PawPaw’s open arms for a hug before my bare feet hit the stained and peeling vinyl floor. He’s a thin and wiry man, not much bigger than I am. He’s clean-shaven and smells like cigarettes, coffee, and Old Spice. His grey-speckled black hair is slicked back with oil from a jar in the bathroom that I couldn’t smell over his aftershave, and he’s wearing a clean but oil-stained long-sleeve collared grey work shirt and similar heavy-duty brown pants. His thick leather tree-climbing boots have deep scuffs from the climbing spikes that he wore on weekends and looked almost exactly like the spurs cowboys wore on the small black and white television across from my couch. I step into his open arms and we hug and he chuckles and squeezes the sleep out of me.

I step back and ask, “We gonna climb trees today, PawPaw?”

He says, “No, Lil’ Buddy. Wendy gonna pick you up today. You can help t’morrow.”

I must look disappointed, because he says, “But MawMaw’s almost outtta milk and cookie dough, so we can walk to d’ store and get some.”

I perk up, and he shoos me towards the bathroom. I step our of our hug and I scuttle to the bathroom before anyone else wakes up and uses it. I pee and pull up my underpants and crawl onto the stool PawPaw put by the sink. I wash my hands and put on the clothes MawMaw had laid out the night before. They smell like laundry soap, and I’m ready for the day to begin. I’m so anxious that I dart out the bathroom and almost run into MawMaw. She’s in her clean but worn bath robe that many years before was probably bright white. It only smelled like laundry soap once a week or so. She’s smiling broadly despite not having had her coffee yet, and she says, “Good morning, Hon!”

I tighten my arms against my body and shrug my shoulders towards my ears, knowing what’s about to happen.

She pulls her elbows back like coiled springs and squats down. I giggle and tuck my arms closer to my chest, raise my shoulders closer to my ears, and lower my chin like a turtle retreating into its shell. She squats down farther, and from my lowered gaze I see her knee-length robe lower and cover her fuzzy off-white slippers still stained from coffee spills. She squats so low that she’s almost eye to eye with me, and I risk a glance up to her face. Her eyebrows are narrowed with concentrated focus, and her hands are moving slowly towards me, as if she were trying to catch a crawfish in shallow water and didn’t want it to scoot away. Like a crawfish, I point my butt towards safety, just in case I need to scoot away and escape down the hallway.

She says, “Gimme some shugga’!”

I retract my arms and chin further into my imaginary shell. A guffaw escapes my lips.

She inches closer, patiently getting within striking distance to snatch me up and gobble me whole. I pull my arms in tightly, and keep my butt pointed down the hallway.

Her smile morphs into pursed lips as she tries to restrain laughter, and she says again, “Gimme some shugga’!” And then, menacingly, she adds, “Or I’m gonna take it!”

I try to stifle my giggles so I don’t wake the baby sleeping in my old room, where Linda and her husband, Craig, were still sleeping; she was a newborn, tiny and shriveled and with a messy mop of black hair, and MawMaw told me that sleep was important so we had to let her rest when she was quiet. Every Saturday was the same and I had to be reminded to be quiet while getting ready to help PawPaw, though usually MawMaw caught me in the kitchen, not in the bathroom across from the baby’s room. I try extra hard not to laugh so close to Linda and Craig’s door. MawMaw senses my momentary lapse in shugga’ defense, and she darts forward. Her hands grasp my shoulders before I can scoot away, and I thrash like a bass trying to throw a hook. But there’s was no escaping MawMaw’s clutches when she’s intent on giving me some shugga’, and she lands a few smooches on my cheeks and forehead despite my thrashing. I squeal in delight.

She puts a finger to her lips and whispers. “Shhhh. Everyone’s still asleep.”

I lower my guard, and she swoops down for another round of shugga’. She turns into a shugga’ sniper, precise and wasting no rounds, landing a smack every time I wiggled and exposed a cheek. I have no chance – I feel the smooch on my left and slam my head to that side, exposing the right. She snipes the right, and I overcompensate to that side and she catches another on the left. I squeal again, and she shushes me again.

She stands up, slightly out of breath, and says, “Go help PawPaw make breakfast, Hon.”

She pats me on the back to encourage me to rotate and walk towards the kitchen instead of scooting backwards, then steps into the bathroom. I wait for the door to shut before relaxing; you can never be too cautious around MawMaw.

I walk past the full-length hallway mirror, stroll into the kitchen, and climb onto the stool PawPaw keeps by the sink for me. He’s standing and making a pot of coffee for everyone else. From my perch on the stool, I’m almost as tall as he is.

PawPaw pours two bowls of Rice Crispies and slices a banana across the tops. He pours in the last of MawMaw’s milk, and the little Rice Crispy elves go Snap! Crackle! and Pop! I giggle and dig in from my perch by the counter. The kitchen table is behind us, between the counter and the refrigerator, but it’s cluttered with my Lone Ranger cowboy hat and wooden train set from Christmas, a scattering of PawPaw’s tools, and a couple of big packages of diapers with a picture of a smiling blonde baby that looks nothing like the shriveled black-haired raisin sleeping in my old room. We hadn’t eaten on the table since Craig and Linda moved back with the baby.

We’re finishing breakfast and MawMaw walks in looking like a different person. She’s wearing a flowery sundress, and her grey hair is stacked in an improbably tall beehive that probably took a full can or two of hairspray; even from across the kitchen, I can smell it over PawPaw’s aftershave. Her lips are painted bright red, and I know that when she gets closer I’ll smell the makeup counter at Dillards in Cortana Mall.

She walks over and threatens to give me some more shugga, and I giggle and began to coil up again, this time like a rattlesnake sitting atop a rock. But she gives some to PawPaw instead, a single smack of shugga’ that he doesn’t try to resist, and pours herself a cup of coffee.

PawPaw was Mr. James “Ed” White, and would be mentioned by Judge Lottingger as saying that the Whites grew “to love Jason as their own” when Lottingger would remove me from their custody a few months later. PawPaw was the same age as my grandfather, and had coincidentally been born in the forests surrounding Woodville, Mississippi, where Big Daddy was born. Unlike Big Daddy, he joined the military voluntarily to serve in WWII, where he lost an eye on a destroyer somewhere in the Pacific. His shipmates would describe him as “a force of nature” who was “always smiling” and “mischievous,” a “fearless sailor” who was an on-board Robin Hood, sneaking into officer’s quarters and stealing their beer to give to enlisted men; a few literary types described him as Puck from Shakespeare’s Midsummer’s Nights Dream, the mischevious but benign woodland elf whose pranks set stories in motion. PawPaw was discharged after losing his eye and returned to Woodville. But there was no work if you weren’t in a union, so he migrated to Baton Rouge and became the custodian and groundskeeper of Glen Oaks High School. As a side gig, PawPaw was the most respected tree surgeon in all of southern Louisiana. Every spring, he was busy repairing damage to aging stately oaks on big homes and plantations as far away as Saint Francisville – with names like The Oaks, Oak Alley, and Live Oak – and removing branches and patching breaks with black goo before termites woke up. A spring a few years before, PawPaw dropped all of his work and rushed to the daycare near Glen Oaks where Wendy had left me because his daughter, Linda White and my mom’s best friend at Glen Oaks, was my emergency contact and she called him and said I was alone and crying. PawPaw took me home and called the police, and Judge Pugh of the East Baton Rouge Parish Judicial District #19, removed me from both of my parents’s custody and made him my legal guardian.

MawMaw was born Delores Shackleton, like the famous explorer who kept him men safe when they were trapped in ice for a year, named after her first husband. Her maiden name was Lamar, of the Baton Rouge Lamar family that owned all of the billboards around town; they’re now known nationally as the Lamar Advertising Company. According to their website and SEC stock listings, they own approximately 80% of all billboards in America and consult internationally on outdoor advertising, and you can tell which signs are theirs because of the small, green, rectangular “Lamar” logo at the base of each billboard. I never learned how the daughter of Baton Rouge’s wealthiest families married groundskeeper of Glen Oaks High School – I wouldn’t know her maiden name until I was researching this book 40 years later – but not that I know her history, I know that if you’re driving down the highway and see a Lamar billboard, it’s a sign of how we’re connected to the same stories.

Together, MawMaw and PawPaw were legally responsible for me and dictated that my parents could see me once a month, and that Wendy couldn’t keep me overnight. For my perspective and though I never used the words, MawMaw and PawPaw were my mother and father.

I don’t recall what PawPaw and MawMaw were chatting about over coffee that morning, but I know that I kept a cautious eye on MawMaw. More than once, she had finished her hot coffee but held the cup, anyway, just to dart in on me just when I let my guard down. I watch her sipping her coffee and leaving red splotches of shugga’ on the rim. She notices me watching and feigns putting her cup down, and I giggle in anticipation. She leans in and pecks her head this way and that, looking for an opening on my cheek like a hen pecking for a bug in the grass.

Between my guffaws and giggles, I hear Craig and Linda taking their turns in the bathroom. That triggers MawMaw to get serious, and she tells me Wendy is coming and to make sure I’m dressed and ready. In my most self-assured tone, I tell her that I know Wendy’s coming, and I point out that I’m already wearing my traveling clothes.

PawPaw tells MawMaw that we’re walking to the store and will be back in a minute. She says she’ll clean up dishes, and gives him another smack of shugga’. He turns away and grabs a russet potato from a half-full bag on the washing machine, and we step through the carport door and weave around stacks of bright yellow phone books between MawMaw’s car and the house. PawPaw stops by the refrigerator-sized cricket cage and pulls out his Old Henry pocket knife, opens the long blade, and cuts the potato into a few chunks. He tosses them into the cage.

“Crickets need breakfast, too,” he says. A hundred crickets chirp in agreement. Beside their cage are tall cane poles with fishing line, hook, sinker, and red bobber; and one fancy spinning reel Big Daddy had given me a month ago. PawPaw puts away the Old Henry and reaches his left hand down, and I clasp it with my right hand. Together, we stroll up the gravel driveway to the blacktop, turn left, and walk through the overgrown grass and thistles along Foster Road. PawPaw’s between me and the blacktop. Cars speed along the blacktop and aren’t used to people walking beside it, PawPaw had said, which is why I hold his hand when we walk to the store. Along the way, I wave my left hand across the tops of grasses that are almost as tall as I am, enjoying the tickle against my palm and watching the blades spring back up unharmed, as if we’re elves passing by without leaving a trace, or like when I went hunting and gardening in the Achafalaya Basin around my dad’s house, walking at night without leaving trails.

We reach the tree on our side of the intersection with the Plank Road a traffic light. Cars are backed up, waiting to rush to the airport or I-110 onramp. I lurch forward and PawPaw lets my hand loose. I run towards the mighty tree.

Eighty-foot long branches draped in grey Spanish moss undulate from the trunk and sprawl in all directions. I reach for the swing and curve my fingers around the textured bark. It’s easier to grasp than the metal gate, but even though I heave and heave I can’t pull myself off the ground. PawPaw walks behind me. I feel his hands under my arms, and I gain the strength to pull myself up and into the cradle. I pause with a leg on either side, and then I’m looking up, trying to reach another branch. I can’t, but I can grasp a handful of Spanish moss instead. I pull it down and make myself look like an old man with a grey beard. PawPaw reaches up and grabs a handful for himself, and we stare at each other’s bearded faces and laugh like two old friends.

“Aw right, Lil’ Buddy,” he says. “We gotta go. Wendy gonna pick you up soon.”

He sets his moss on the branch and reaches up both hands for me. I keep my moss and swing my leg over and drop into his arms. I hit the ground, take his hand, and we walk to the traffic light and wait to cross. Outside the store’s glass door, I put my beard back on and check my reflection before PawPaw pulls the door open. The man working behind the counter flashes his big white teeth. He’s talking to PawPaw, but he looks down at me and says, “Hey d’er, Mr. Ed. Who y’ got with you today?”

I giggle and whip off my disguise and tell him it’s me. He’s surprised and tells me he didn’t recognize me. I put the beard back on, and he says I look just like an old tree elf. Of course I did! It was intentional, but he probably didn’t remember that even though I had told him before. We chat while PawPaw gets a tube of chocolate chip cookie dough, the one with a package showing Keebler elves baking cookies in a house that looked like a stately oak tree but with shorter branches. He also picks up a carton of Blue Bell milk and a six-pack of Miller Lite pony bottles. The man laughs at something PawPaw says, then reaches up and pulls down a pack of unfiltered Camels cigarettes. The man puts everything in a brown paper bag that makes crinkly noises when PawPaw holds it to his chest with one arm. We say goodbye and walk out.

I take PawPaw’s free hand and we cross the intersection. I stop at the tree and I place my beard on a branch I can reach, imagining it will grow more moss for next time. We walk home and I rattle on about how I can climb the tree all by myself now. He says of course I can, because I’m Jason Partin. He pronounces my name in his mumbled Mississippi accent, Par’un, almost like one syllable drawn out and allowed to linger a bit, and tells me I can do anything I want if I keep trying. I beam and skim my hand across the weeds and ponder what else I wanted to do now that I could do anything. I could probably climb that gate.

At home, we put away the groceries and PawPaw sits at the kitchen table. He puts a Camel in his mouth and pulls out his dented silver Zippo. Before he flicks it, he pauses with his head tilted down and his eyes up and focused on me. I see that his cigarette is backwards again, and I tell him the little camel is away from his lips and will burn up if he lights it. He chuckles and thanks me and flips the filterless cigarette around, and tells me how smart I am and how lucky he is to have me paying attention for him. He lights the proper end, takes a drag, and holds it in one hand while he pours another cup of coffee from the full pot MawMaw probably made while we were gone. I can hear her in the back, laughing with Linda and Craig. The baby’s still silent.

I hear crunching in the gravel driveway just before the smoldering tip of PawPaw’s cigarette reaches the little printed camel. PawPaw puts it out and walks outside through the carport door, and I follow. The car that pulled up is a faded yellow Datsun hatchback with its put-put-put engine. I know it was a Datsun because that’s what PawPaw called it: not a car or the car, but the Datsun, probably to identify it from the other cars that were sitting behind the barn waiting to be brought back to life like the Datsun had. I rush towards it and hear crunching sounds every time one of my feet hits the gravel.

I reach the passenger side and Debbie squats down as best she can – she’s stout and moves slowly – and opens her arms and I fall into them and we give each other the biggest hug ever. Wendy comes around and squats down and waits for me with a longing look in her eyes. She effortlessly lowers down to my height. She’s a bit taller than Debbie, but fit and athletic. I leave her and rush to Wendy, and she smiles more like her usual smile, with old-lady crows feet crinkles around her hazel eyes. She opens her arms, and tells me she’s happy to see me. I step into her arms and hug her and I say I’m happy to see her, too.. They both smell like cigarettes and pot, though I’m not supposed to use that word.

PawPaw says they’s running late, so we should hurry. He begins unloading stacks of Yellow Pages from MawMaw’s car and loading them into the Datsun’s hatchback and back seat. Another one of PawPaw’s side gigs was running seasonal work for Kelly’s Girls, the national chain of temporary work with flexible hours and geared towards young, single mothers so that they could attend school while working. Other contracts included secretarial work at the chemical plants along the road to Saint Francisville, but PawPaw didn’t have those. He had contracts for delivering Yellow Pages in spring and pre-Christmas shopping catalogs in fall, and any similar temporary deliveries; that’s why he kept a few used cars ready to give away.

Debbie, Wendy, and I help PawPaw stack Yellow Pages into the Datsun’s hatchback, and then into the back seat. Soon even Debbie’s passenger floorboard is filled. The only space left is for me is atop a few of the yellow books in the back passenger seat. Debbie and Wendy and PawPaw step back to inspect the work and smoke cigarettes and talk and laugh. I stand beside them, pretending to be grown up, too. PawPaw points out that the Datsun has squatted down a few inches like a mule with knees buckling under the weight of its load, and they laugh out loud and I laugh with them. When they’re done smoking, PawPaw boosts me up to sit atop the stack of Yellow Pages.

My feet rest on the books piled into the floorboard. I can see out the front window from my perch. To my right, I see Wendy and Debbie saying goodbye to PawPaw. They get in, and Wendy turns the key a couple of times until it shudders to a start. She puts it into first gear, lurches forward, and it stalls. They laugh, and Wendy says something about learning how to drive a stick. She restarts on the first try, and we lurch forward again. I hear the gravel shooting up as we accelerate and turns right onto the blacktop. We snap forwards as she shifts into second gear, then backwards as she accelerates. Soon, we’re in fifth and flying north on Foster Road.

The route she always took from PawPaw’s passed a small public park, barely the size of the patch of grass in the front yard of a crowded neighborhood. It has creaking swings, a wobbly merry-go-round, and a couple of humongous concrete sewer tubes for crawling over and in and out. It’s near a 7/11, which is like a convenience store but without a tree to climb. We stop to get Slushies, and they get Coke again. I stick with cherry, because it’s the sweetest and because it turns my lips red, like azaleas and MawMaw’s lipstick. We park at the park and sit inside to slurp our favorite flavors.

Debbie and I swap a few sips from our cups, and Wendy turns on the radio. A song comes on, and they squeal. Debbie turns up the volume, and they begin singing along to Janis Joplin’s song about Baton Rouge. Wendy turns towards me with her crinkly smile, and they sing: “Busted flat in Baton Rouge, waitin’ for a train… Feelin’ nearly faded as my jeans…” 2

I sing along a beat behind. When Janis says the windshield wipers are markin’ time, I stop trying. I let Wendy sing the words she knew so well; I’m just along for the ride. Debbie finishes rolling a dainty joint, runs her tongue along the flap, and drags her thumb along the seal. She puts away her little hand-sewn pot bag with all the blue and red hand-sewn flowers on it, cracks her window, and lights the joint with her Bic. She takes a drag and passes the smoldering joint to Wendy.

Magically, without exhaling, Debbie sings the part of Me and Bobby McGee about a dirty red bandana. Sometimes when I rode with her, Debbie wore a faded blue bandana around her neck like a cowboy, and sometimes she folded it into a triangle and wore it like a pirate’s hat atop her straight dark black hair. I never saw her blow her nose or wipe out sawdust with it, like PawPaw did with his white one. PawPaw told me that the Lone Ranger wore a white hanky so people knew he was clean, and to keep sun off his neck and soak up water from shallow springs for Silver. But Debbie and I always played in the shade and we never rode horses, and Louisiana has water overflowing from every river and drainage canal, so I think she just liked wearing a bandana that matched her little blue bag and reminded her of Janice.

Me and Bobby McGee finishes and Wendy turns off the radio. The joint wasn’t finished, and Debbie keeps me entertained while they smoke by teaching me a new magic trick. She used to pull my nose off and put it back on, but I eventually realized it was Debbie’s thumb, not my nose. She showed me how to make it look like I pulled off her nose, and I got so good at it that I could fool PawPaw and MawMaw every time, even when I did it three or four times in a row. But, on that Saturday, Debbie pulls of her thumb and I’m stumped. I giggle. She does it again. I giggle again, but I think I see how to do it and try. I fail – I keep my right thumb straight and beside my fist, and it looks nothing like holding my left thumb. She shows me how to tuck my thumb inside my fist and poke the tip between two fingers. I try again, and it looks better. But, I can’t nail it down quickly like the nose trick. I keep trying with Debbie’s oversight and occasional input between hits on the joint. Smoke hands in the air, and we keep practicing until the joint is a roach too small to smoke. They toss it out, and we finally go play on the merry-go-round. I’m feeling fine, so high I can touch planes flying in the sky.

They take turns spinning me around and around, faster and faster. I go higher and higher with each turn, because the wobbling makes a steady arc, higher on the side away from them, and bringing me back to their eye-level on the down swing. The creaks of old and neglected bearings made a melody sweeter than anything on the radio, and the greens of the trees are more vibrant than ever before. The red azeleas blur around me, and I look up at the bright blue sky and see a few puffy white clouds swirl. I giggle dizzily. They stop pushing, and the merry go round squeaks get farther and farther apart until I’m stopped, spent from laughing so hard and so long.

Wendy’s won’t stop laughing. She walks over to azelea bushes under the noontime shade of a few tall pine trees. She picks a red flower, tucks it above her left ear between strands of her long straight strawberry blonde hair, and skips back and sits beside us. She stands on one of the thick sagging plastic swing seats, grasps the chains with both hands, and leans back while pushing her feet forward. She begins swinging, and sports the sweetest smile you’ve ever seen. Her eyes are crinkled like an old lady’s crow’s feet, a smile that I notice more when it’s not there than when it is.

On the way home, we stop at Brian the one-armed drug dealer’s house. It’s full of people passing joints under Brian’s big oak tree. Cindi, Debbie’s sister, is there with her baby. They all seem to know who Debbie and Wendy well, but Cindi and Brian are the only one who calls me by my name. Craig and Linda hadn’t been there since they moved back, though Craig’s paintings of moss-draped trees and swamp elves adorn the outside walls. Without Craig and Linda there, Brian is the only person who talks with me. He says he’s happy to see me, and he shows me the motorcycle he was trying to modify so that he could ride again. He heaves me up with his arm and sets me on the seat and shows me how to pull the new cables on the right handle that pull the clutch on the left. It’s a fine motorcycle and I like Brian, but I say I’m hungry and I would like some cookies. It’s all I can think about. He apologizes and said they don’t have any. I must look disappointed, because Wendy stepped over and says she’ll take me home. She says it would be just us, because Debbie is staying. I look over and see her sitting cross-legged, under the shade of Brian’s oak tree and surrounded by Cindi and their friends. Her little bag is out on the big wooden power-line spool Brian used as an outdoor table. She’s rolling a joint with both hands; Brian could have done it with one. She pauses rolling and waves goodbye. I wave back, and Wendy and I get in the Datsun. I get to sit in the front seat this time. We wave goodbye to everyone, and move forward smoothly; Wendy had gotten better with a stick after practicing stopping and starting at each house that received a yellow phone book. We drive along Foster Road with the windows rolled up. It’s warm and windless inside. I doze off.

I wake up to Wendy shaking me. Her head’s turned away and she’s talking to a man whose face is peering into her window. I had never seen a police officer before. His shiny gold badge flashed blue and red. I stared, mesmerized. He glances at me smiles the same smile as Brian. I feel fine. He looks back at Wendy.

“I’m sorry, officer,” she says, still shaking me. “My brother’s sick and I was trying to get him home. I was scared and didn’t know what to do.”

He looks at me again and gently asks, “What’s your name, son?”

“Jason Partin,” I say, pronouncing my name like Debbie did, with a Cajun accent and two clear syllables: Pah’tan. Her name was Debbie LeBeaux, pronounced L’Bow, like bow and arrow, or like the LSU football chant, “Geaux Tigers!” She pronounced my name like the women I saw in a commercial for Patin the Plumber, the one where a woman sees her overflowing toilet and wags a finger at her puppy-dog faced husband and says, “You shoulda called Pah’tan!” Most adults, other than Debbie and PawPaw, pronounced my name like the big bosomed country singer, Dolly Parton. Even Wendy said it that way. I don’t know why I pronounced it Pa’tan for the officer, but I assume Debbie had been teaching me new French words at some point, or she may have said my name in her accent and it stuck. Or, I may have been so high from second hand smoke that I couldn’t say my own name. The officer is holding what I now know was Wendy’s driver’s license. He gazes down at it and then back up at me, and his smile broadens.

“I hope you feel better, Jason,” he says. Glancing back at Wendy, his smile fades and he says that she should slow down and get home safely. She laughs awkwardly and says she will, and takes her license back with a shaking hand.

He stands back, and Wendy drives forward so slowly and smoothly that I don’t notice at first. For a moment, I’m confused. I watch the officer slide backwards without moving his legs. He goes out of sight, and I lean between the seats and peer at him and his car behind us. I keep staring backwards at his car. On it’s roof, red and blue lights revolve. Their reflections pulse on his badge and reach us inside the Datsun. He must have seen me staring, because he smiles and waves. I smile and wave back, and then I notice his Batman utility belt. It has a revolver pistol like The Lone Ranger’s, and lots of impressive gadgets. I decide I’d like to be like him, whatever he is, if I got to wear a Batman utility belt. I turn around and look ahead. Wendy’s leaning forward, and her hands are clutching the steering wheel. She’s shaking slightly.

My body reminds me how hungry I feel. Fortunately, we’re driving along a part of the blacktop that I know isn’t too far from home. Wendy nervously tells me not to tell Mr. White that we got pulled over by a cop. I say okay, and figure it’s a secret like Debbie’s pot bag, or how to make your thumb look like someone’s nose. Besides, it wasn’t important compared to how hungry as I was. We turn left into PawPaw’s driveway and stop, and I open the door hop out before Wendy turns off the car. My feet land on the gravel with a satisfying crunch, and I immediately run towards the carport. MawMaw opens the door and steps into the frame. I rush past her car and she squats down and opens her arms. I leap into her hug. She squeezes me, and says, “Gimme some shugga!”

I squeal in delight and try to escape her arms and she has a huge grin and says, “I’m gonna get me some shugga!” I squeal again and abandon trying to escape, and instead I throw up my hands and cover my face in defense. She has that bright red lipstick on, and I know what that means. Despite my best efforts, she manages to plant several red stains on my cheeks, forehead, and backs of my hands; every time I had covered one spot, I left another spot exposed. Like I said, she was an expert shugga’ sniper, so I didn’t have a chance.

She says, “Tell Wendy goodbye.” I turn around and wave goodbye. Wendy’s standing beside the Datsun and waves back. Her smile is gone. I quickly turn around and rush inside and wipe off the red shugga’ and to wash my hands so I can eat some cookies. I pause at the hallway mirror and inspect my face. MawMaw was good. She had planted a few smeared red smooches on each cheek, and a perfectly shaped pair of red lips on my forehead. I step into the bathroom and onto my stool and turn on the faucet and scrub them all off.

Back in the kitchen, MawMaw already has a plate of cookies and a glass of milk waiting. Outside the window, I see smoke from PawPaw’s fires, and a few of the big men who worked for him tossing branches onto the flames. His truck is just outside of the gate. MawMaw asks what I did all day. I show her how I could take off my thumb. She’s impressed, and makes a serious face and asks how I did it. I tell her it’s a secret, and that a magician never tells secrets. Instead, I tell her about the big, fancy houses Debbie and I ran to and from while delivering Yellow Pages, and about the Slushies and the merry-go-round.

I finish the cookies and help MawMaw wash the plate. She tells me to go watch television so that she can make dinner. I go into the living room, push the television on and rotate the dial until I find the reruns of Adam West as Batman that came on every Saturday afternoon, just before The Lone Ranger. I crawl onto the couch and think that the man today had a better utility belt than Batman. I grab a few tools from off the coffee table and shove them in a leather work belt pouch and begin making my own utility belt. I hear PawPaw comes inside and MawMaw tell him where I am. He walks in smelling like diesel smoke and chainsaw oil, and says, “Hey d’er, Lil’ Buddy. Whatcha makin’?”

“A utility belt,” I say. “Better than Batmans!”

He chuckles and tells me that’s a smart thing to do. He goes to the bathroom to take a shower, and I practice whipping tools out of my utility belt smoothly and invisibly, getting them to my hand before anyone notices.

I wake up early Sunday morning to the smell of PawPaw by my side, wash my hands, and make myself a bowl of Rice Crispies, with the little elves on the box that go Snap! Crackle! and Pop! PawPaw said we’d be burning wood after one of the helpers shows up, and then I could help both of them.

I look out the window, and between the pond and the barn I see piles of tree limbs by the pond that PawPaw had unloaded last Sunday, next to his rusty pickup truck. I can’t recall which type of truck – I’ve never been good at identifying automobiles – but it was probably a late 60’s Ford F150. Most big trucks look the same to me: beds littered with rusty tools, a giant steering wheel, and a single bench seat so high up that even PawPaw has to climb into it. They all had the same thundering rumble you felt in your chest, thump-thump-thump, unlike a car’s weak put-put-put. PawPaw’s tuck had dents and dings and holes from rust, and the dark rust blends in with the bark of trees so perfectly that most people wouldn’t give it a second glance, which is why I look twice to make sure it’s not there. He used it on weekdays to go to his gig at Glen Oaks; whether or not I saw it around the house was like a calendar for me, telling me whether or not I’d get a whole day with PawPaw.

Big Keith Partin, pronounced like Dolly Parton, shows up. He has short wavy blonde hair and a thick country accent similar to Dolly’s. Unlike PawPaw, he speaks clearly and slowly, more like a charming drawl than what most people would call a redneck or coonass accent. He’s my dad’s little brother, but he’s a giant, like all Partins except me. His frame fills the carport door, and he makes PawPaw look as small as the elves on the box of Rice Krispies. He looks just like Big Daddy, with the same blue eyes, bulky frame, and perpetual smile, but obviously younger. He smiles like a big kid. He ducks his head and twists his broad shoulders to step inside, stands up in front of the washing machine, and his head almost touches the ceiling. He tells me I’ve grown. He asks me to make a muscle, and I do. So does he. His is bigger, and he laughs gently and says hard work and exercise makes you stronger. His sky blue eyes twinkle.

We walk past the gate and to the pond between the house and barn. Keith and PawPaw begin burning piles of wood, strategically placing the piles atop fire-ant mounds. The name isn’t a coincidence – they’re called fire ants because when you step in their mounds, an army races up your leg and 10,000 little but painful scintillating fires ignite your skin and send your mind racing, not knowing which part of your body to dose first. Diesel is like napalm to their army, and it’s worth the risk of dousing yourself when you’re attacked. I’m not allowed near the fire ants and diesel fires. Keith reminds me about my dad’s leg scar from pouring gas on his fire ants, and the gas catching on fire.

PawPaw takes out his cigarette and says, “That’s why we use diesel. It don’t burn as easy as gas do.” He puts his cigarette back between his lips and pours diesel on a fresh pile of branches stacked atop a knee-high ant mound.

Keith carries a branch bigger than PawPaw from the back of the truck and heaves it onto the pile. The smoke rises, and they go to and from the barn, hauling wood and trash to be burned.

I had forgotten to bring my cane pole and mesh cricket tube, and I’m bored. I look up at the gate. It’s leaning against the thick round pine-tree poles that used to hold it up. It’s much taller than the barb wire fence that circles the old cow farm. It was taller than Keith, probably eight feet or so and almost just as wide, with about six round horizontal bars going to the top. I grabbed one and put a foot on another. It didn’t have the texture of tree bark and was slippery, but I moved upwards anyway. Soon, I’m grasping the top bar with my right hand, the stronger one, and I swing my left hand up and feel myself move closer to the sky. I reach the top bar for the first time. But, before I can celebrate, my feet slip off. I hold on with both hands curved over the round bars for a brief moment, dangling as vertical as a plumb line, but I can’t keep my grip and I slip off and start falling. I hit the ground and remarkably land on both feet with my knees bent. Before I feel the pain in my knees or can straighten up, the gate comes crashing down on my head. I crumple under it’s weight.

On the ground and with the gate atop of me, I scream louder than I ever had before, louder than PawPaw’s truck or a jet airplane or even that shriveled raisin sleeping in my room when she wakes up. I’m trapped, unable to do anything but try to purge the pain with my screams.

“Ed! Ed! I hear Keith yell. Come quick! It’s Jason!”

I could hear myself screaming and could see the world turned sideways. Keith was at 90 degrees, running towards me with huge strides made by his long legs. His big booted feet crush branches and weeds, and the earth trembles with each step. Behind him is a dark cloud of diesel smoke rising from one of the freshly lit piles. He shouts: “Ed! Jason’s hurt! Come on!”

PawPaw’s tiny frame bursts through the smoke. He’s running so fast that it looks like he’s flying over the ground, never stepping foot. His legs are a blur of motion. I’m still screaming, seeing everything unfold as if watching a television show while lying sideways on the couch.

Keith reaches me first and heaves the gate off me as if it were a small branch to be discarded. He picks me up and cradles me in an arm and shouts: “Oh God, Ed! He’s bleedin’ bad! Hurry!”

“Get in d’ truck!” PawPaw yells. He’s waving an arm as he runs. “Get in d’ truck! D’ passenger side. Go!”

Keith reaches the truck in a couple of strides and flings the creaky door open and slides inside with me cradled in his left arm. My feet touch the door and my head is by the steering wheel. I’m shrieking. Dark red blood pools in the cracked vinyl bucket seat so quickly that it forms lakes in the indentations. Blood flows like rivers along cracks in the vinyl, and red waterfalls cascade into the floorboard by Keith’s feet. I haven’t stopped screaming.

PawPaw flings open the driver’s door and leaps in. In one smooth motion he slams the door and cranks the ignition and throws the steering column shift into gear and accelerates faster than I had ever felt that truck go. My head flops backwards, and Keith adjusts his arms and exclaims something about all the blood. The truck kicks up gravel as we pass the house. PawPaw takes a hard left and sends a wave of rocks skittering across the blacktop. Momentum drains the lakes of blood onto the floorboard, and I’m steadily filling them back up with a fresh supply.

“Oh God Ed! He’s bleedin’ bad! Hurry!”

No one had to tell PawPaw to hurry: he’s force of nature hell-bent on savin’ his Lil’ Buddy. The truck engine roars louder than it ever had, and the universe buckles to PawPaw’s will. We fly down Foster Road and hit Plank Road at full speed. PawPaw’s arms strain to pull the big steering wheel hard enough to make the turn. In mid turn, he sticks his head and left arm out the window and waves his white handkerchief up and down, higher than the roof and then back down, again and again and again, a white blurred arc shining bright enough for the world to see. His right arm is shaking from holding the steering wheel by itself, yet he pulls it with will power that would have steered the Titanic free from harm. Tires screech and we skid through an improbably sharp left turn. He’s shouting: “Get out d’ way! Get out d’ way!” The universe abides, and the river of cars along Plank Road parts like the Red Sea did for Moses.

I’m cradled in Keith’s arm and probably below the level of the window, but through the lens of my memory I see the oak tree and its branch with my swing pointing us the right way. Regardless of whether I actually saw the tree or not, the momentum of our sharp turn makes my head flop over, and the tree vanishes from my mind. All I can see is blood flowing with the same momentum that moved my head, splashing around Keith’s feet. He shouts something. I’m drained and unable to refill the lakes. I loose consciousness.

I wake up to the smell of PawPaw. I open my eyes and see him sideways, like when I wake up on the couch. I sit upright. He’s asleep on a chair next to me. He reeks of body odor and chainsaw oil and cigarettes, and he has thick stubble on his chin and cheeks, grey as the moss on our tree. He wakes up and sees me looking at him and and smiles, but his eye belie his fatigue; I say eye, not eyes, because that was the first time I noticed that PawPaw’s left eye was never bloodshot; more than forty years later, Craig would tell me PawPaw lost an eye on a destroyer in WWII. That day in the hospital, I see that his left eye is as it always has been, but his right eye is streaked with red blood veins. Under that eye, the leathery creases in his dark tanned skin are caked white with dried salt. He looks as if he is squinting with his bloodshot eye, as if all the lubrication where gone and his eyelid wouldn’t slide all the way back up.

“Hey d’er, Lil’ Buddy,” he says. “’Bout time you woke up.”

He pulls out his handkerchief, now dirty and stiff in places, and sniffs, wipes deep inside his nostrils, and smiles the most grateful smile you’ve ever seen.

I’m in Our Lady of the Lake Hospital’s children’s ward, though that’s a lie: they have no lake, so I can’t go fishing while I stay there. I have a shaved head and I’m wearing a turbine made from bandages. The gate scalped me, cutting a gouge along the back of my head, peeling a flap loose and exposing my skull and shredding my veins. The nurses change the bandage, and use two mirrors to show me a big letter C on the back of my head. PawPaw tells me I have 82 stitches, that they needed a lot of room to put the second brain inside.

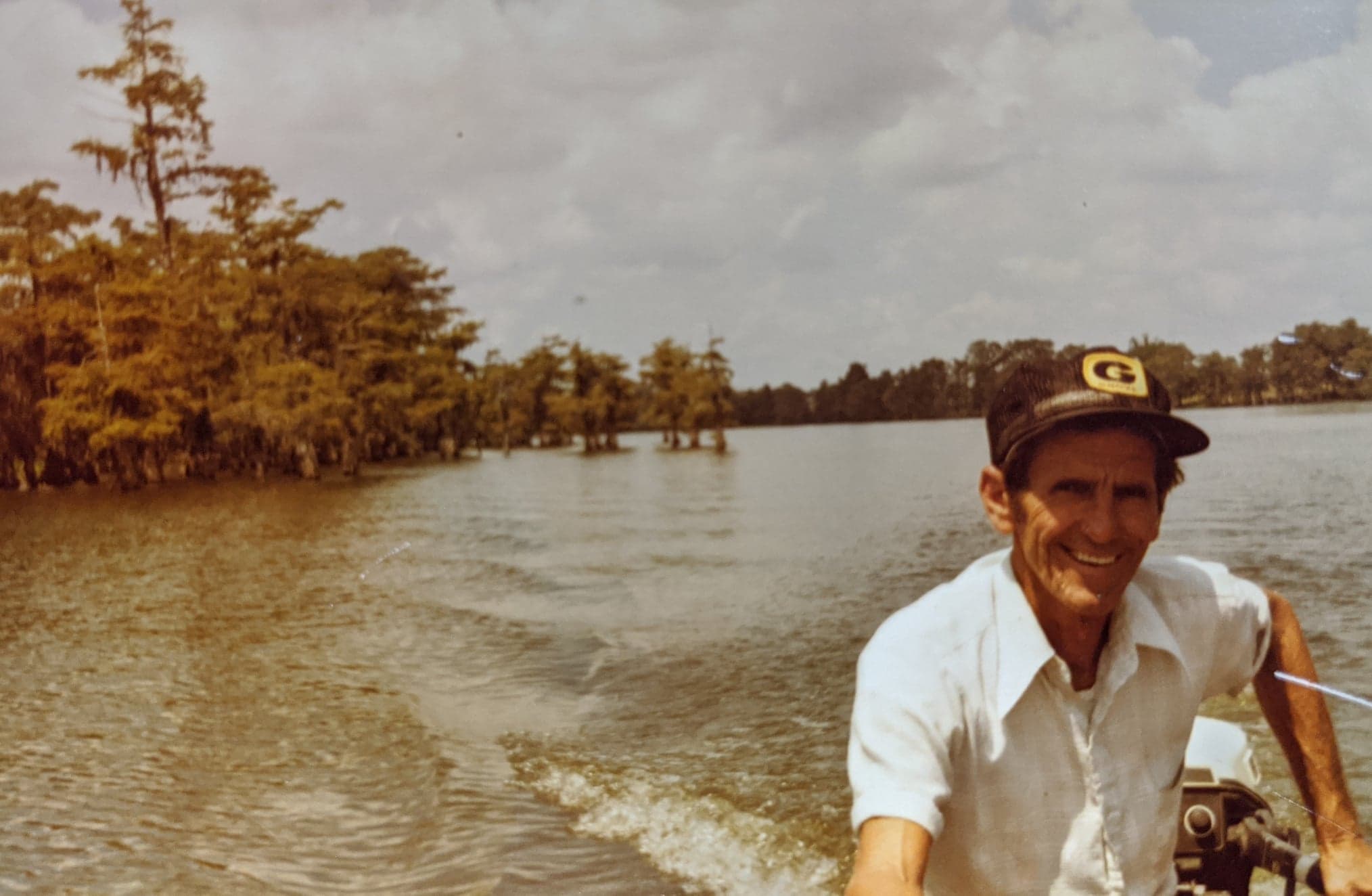

MawMaw shows up and PawPaw goes home to get cleaned up. They alternate staying with me for a few days. Doctors shine a flashlight in my eyes every day and keep asking me questions, like what’s my name, what town do we live in, and who’s my favorite cartoon character. (It was Spiderman.) They must not have been too smart, because they keep forgetting my answers and ask the same things every time they come to see me. I tell PawPaw that, and he says that’s what happens when you have two brains: you remember more than other people. He says I’m the strongest and bravest kid in the hospital, and now that I have two brains I’ll be the smartest person in Baton Rouge. I agree. I feel as strong as he told me I was. I ask if we can go fishin.’ He chuckles and says we’d go fishin’ in the pond as soon as I’m home, or maybe even drive out to False River and fish from the scanoe. I ask when. He says maybe in a couple of days, depending on what the doctors say.

I watch a lot of television while I wait. Our Lady of the Lake had a big color television in the play room, the first time I had seen color TV, much less on a TV as big as a wall. Popeye and Friends comes on Saturday morning after the Buckskin Bill Black show. It was the first time I had seen Popeye; it wasn’t the earlier version, when Popeye was by himself, it was – perhaps coincidentally – when Popeye takes care of Olive Oil and her baby, Sweet Pea, by eating spinach and getting stronger. I think Popeye looks like Pawpaw, especially after seeing PawPaw squinting when I woke up. And, like Like PawPaw, Popeye smokes and laughs a lot and mumbles when he talks. The next time the doctors forget my favorite cartoon character, I tell them it’s Popeye. That causes a commotion, and I have to explain myself. Later, when they forget again, I remind them that it’s Popeye. They don’t ask me to explain why that time.

On my last day, I’m watching Batman and Superfriends on the big color TV. They have back-to-back episodes, and it’s the season where super friends teach magic tricks at the end of each episode. That’s how I learn that Batman isn’t really strong, it was just a magic trick, unlike Popeye. Batman teaches Robin how to break a rolled up newspaper with bare hands when other people can’t. Batman keeps a glass of water hidden nearby, and somehow no one notices that he dips his fingers in it and wets the paper when no one’s looking. He breaks the wet weak paper effortlessly, and seems stronger than he is. I feel let down. It was just a trick. No wonder he needs a utility belt.

But, I’m impressed by Aquaman. He doesn’t use tricks to pretend he’s strong, he makes things vanish. To this day, I still use what I learned in Our Lady of the Lake that spring. Aquaman’s sitting at a table and he wraps newspaper around the bottom of Batman’s empty glass of water. (I assume Aquaman drank the water.) You can’t see the glass, just the shape. He turns it upside down and covers a coin on the table with it. He says he’ll make the coin disappear. He lifts the newspaper covered glass to make sure the coin’s still there, and slowly puts it back down. He concentrates, then slams his hand down onto the glass. The newspaper crushes, but we don’t hear glass break. He lifts the crumpled newspaper and shows that the glass vanished instead of the coin. All of the Superfriends gasp! Not even Superman’s x-ray vision can find the glass, and not even Wonder Woman’s magic lasso can uncover the secret. Aquaman explains misdirection to us. He said he talked about the coin so we would focus on it, not the glass in his hand. When he le let the glass fall into his lap while we watched the coin. He kept the newspaper held lightly, like I hold PawPaw’s Camels so they don’t squish, and it looked like he still held the glass when he set it on top of the coin. The trick was over before anyone knew it had begun.3

During the commercial break, I play with the pile of toys in Our Lady of the Lake’s kids common room. I was shy around other kids, and pushed myself around the room on a wooden four wheel bicycle with handlebars like Brian’s motorcycle. Suddenly, a commercial caught my attention and I stopped moving and stared at the television. The kids on TV had a Stretch Armstrong, a blonde haired strongman that looked remarkably like Keith. The strongest of the kids could stretch Stretch Armstrong’s arms out, holding one arm in each and and heaving like it was an exercise band. The other kids were impressed. They all laughed together, stretching Stretch Armstrong between them. I wanted one. Maybe it seeing something on color TV, or maybe it was seeing the group of kids playing together with it when I secretly wanted to play with the kids in our common room; regardless, I wanted a Stretch Armstrong more than anything I’ve ever wanted before or since.

“I want a Stretch Armstrong,” I tell PawPaw on the way home from Our Lady of the Lake Sunday morning.

I’m riding in the passenger side of his truck. On the bucket seat between us, the foam showing through threadbare vinyl is stained dark red. The floorboard has so much old oil and grease that I can’t see if it’s stained red, too. PawPaw’s clean shaven again and smells like Old Spice again. I say I want to get as strong as Keith, and that takes hard work and exercise. What would happen if Keith weren’t there to lift the gate next time? I need to be able to lift it myself.

“We’ll see, Lil’ Buddy” he says, chuckling like Popeye.

We’re driving down Plank Road. I hold my hand flat out the window, and I notice that it flies up and down like Superman. I imagine I’m flying like superman, higher than airplanes. We gently turn right at the oak tree. It looks smaller now. I must have grown. I’m flying and I’m the bravest little man in Baton Rouge, and I know all the secrets that super heroes know. Only PawPaw knew that about me, though. The kids in the common room didn’t. I just needed a Stretch Armstrong to help me get stronger, then I’d show everyone what I could do. I could do anything I wanted, after all, especially now that I had a second brain.

Go to The Table of Contents

Footnotes:

- PawPaw lived off Hooper Road, not Foster Road. Hooper intersects near Plank a mile east of the Baton Rouge airport, about two miles north of Tony’s Seafood and a few miles west of Glen Oaks High School. Foster Road is farther away and looked similar back then, but more developed and not as walkable. I probably remembered Hooper Road as Foster Road because people would say they were taking me to my foster parent’s house, and we sometimes took Foster Road to get there. ↩︎

- Wendy remembered the song as “Saturday in the Park,” by Chicago, and said that we used to sing the lyrics, “Saturday / in the park / I think it was the 4th of July.” I remember singing that with her, too, especially when we did it on the 4th of July, but never with Debbie. Debbie passed before I could ask her. Debbie adored Janis Joplin and always carried a blue bandana, similar to Janice’s red one, so maybe my mind links the song to being with Debbie and Wendy linked being in a park with Chicago. According to Wikipedia, Me and Bobby McGee was released in 1971, a few months after Janis’s 1970 death, and Saturday in the Park was released in 1972. Both songs were popular on the radio in 1976, and Me and Bobby McGee still is. It was probably played more often in Baton Rouge than Saturday in the Park because of the lyrics about Janis passing through Baton Rouge, which may be another reason it sticks in my mind so strongly when I think of listening to the radio in Wendy’s Datsun throughout the 70’s. ↩︎

- Superman and Wonder Woman didn’t see Aquaman perform that trick. He sat at the table by himself, which is verifiable in internet archives of the Superfriends cartoons that aired between 1973 and 1982. I see the episode accurately in my mind today, because I watched it again, but I remember thinking about Superman and Wonder Woman watching him perform, and that probably clouded my earlier memories. I probably watched so many cartoons in the hospital that I imagined the Super Friends as real people, and knew that that Superman was strong enough to tear Batman’s rolled up newspaper without needing a glass of water, and he could have also seen through Aquaman’s newspaper to know that the glass was already gone, no matter how good Aquaman was at misdirection. As for Wonder Woman’s lasso of truth, it made sense to me that if you really wanted to know a secret, just ask Wonder Woman to use her magic rope; that’s probably why Aquaman wouldn’t performed magic around her. Aquaman, of course, would have already known the secret Batman used to make paper weak with water, because he was Aquaman. As for Stretch Armstrong, Wikipedia says he was a toy released in 1976 and presumably marketed heavily during Saturday morning cartoons, though he didn’t obtain the long-lasting pop culture standing of the Superfriends. ↩︎