Introduction to A Part in History

But then came the killing shot that was to nail me to the cross.

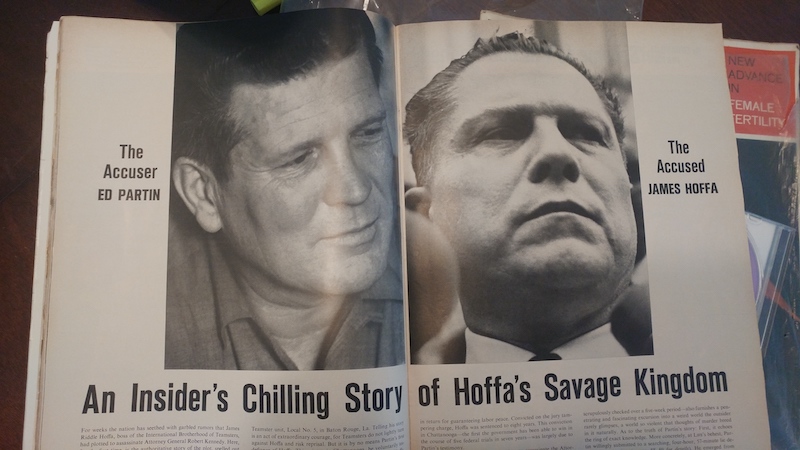

Edward Grady Partin.

And Life magazine once again was Robert Kenedy’s tool. He figured that, at long last, he was going to dust my ass and he wanted to set the public up to see what a great man he was in getting Hoffa.

Life quoted Walter Sheridan, head of the Get-Hoffa Squad, that Partin was virtually the all-American boy even though he had been in jail “because of a minor domestic problem.”

– Jimmy Hoffa in “Hoffa: The Real Story,” 19751

I’m Jason Partin.

Hillary Clinton broke my left ring finger on 03 March 1990; it healed askew, and to this day my two middle fingers have a gap above the middle finger that looks like Dr. Spock’s split-finger salute on Star Trek.

My father is Edward Grady Partin Junior, the rough-edged ex-con who became a public defense attorney listed in the Baton Rouge phone book as Edward G. Partin, Attorney at Law. His 1985 conviction was based on 2.1 pounds of marijuana scraped from the cracks of his attic during a legal search and seizure. At the time, having more than two pounds of marijuana was a felony, and he served his sentence before earning a General Equivalency Diploma in lieu of high school, earning a college degree in history and political science, and then passing law school and successfully suing the states of Arkansa and Louisiana to change their laws to allow convicted felons to practice law, vote in elections, and own firearms.

My dad, just like every law student in America, studied my grandfather; he was Edward Grady Partin Senior, the Baton Rouge Teamster leader famous as the surprise witness whose testimony convicted International Brotherhood of Teamsters president Jimmy Hoffa of jury tampering in 1964, ten months after President Kennedy was shot and killed. At the time, his two year infiltration into Hoffa’s kingdom was illegal search and seizure. Because America’s system of justice is, for the most part, based on predicate cases, my grandfather’s word continues to shape history because it changed how America monitors and prosecutes people without a warrant.

Before my grandfather’s testimony, U.S. constitution’s 4th Amendment unambiguously stated that a warrant was necessary for our government to search or seize private property, and that the warrant must specify what, where, and why something was being searched or seized. U.S. Attorney General Bobby Kennedy and FBI director J. Edgar Hoover Hoffa had freed my grandfather from a Baton Rouge jail and asked him to monitor Hoffa’s inner circle for “something” or “anything” that could convict Hoffa Jimmy Hoffa. Two years later, and though it was only Big Daddy’s word against Hoffa’s, a jury took only four hours to believe Big Daddy when he said Hoffa implied he rig a previous jury.

Hoffa tasked an army of attorney’s to fight his conviction. They challenged the government’s abuse of both the 4th Amendment and the 6th, which, among many things, guarantees a person charged with a crime the right to confront witnesses. Hoffa lost his final appeal in 1966’s Hoffa versus the United States, and began serving eight years in prison based solely on my grandfather’s word.

My grandfather was Edwards Grady Partin Senior, but everyone I knew in Baton Rouge called him Big Daddy. He was big, handsome, and charming. In Hoffa’s second autobiography, published a few months before he vanished from a Detroit parking lot in 1975, he described my grandfather concisely: “Edward Grady Partin was a big, rugged guy who could charm a snake off a rock.” That says a lot after Hoffa spent the final years of his live in prison based solely on Big Daddy’s word.

In 1983, Big Daddy was portrayed by Brian Dennehy in 1983’s “Blood Feud.” He was more famous than Dennehy back then, but the young actor looked so much like Big Daddy that producers cast him and America got their first glimpse at what would be Dennehy’s trademark style: rugged good looks and a charming smile. Practically everyone in America watched Blood Feud, but by then they had seen Big Daddy plastered across media by Bobby and Hoover so much that they knew what to expect.

The iconic actor Robert Blake, whose intense and square-jawed face looked like Hoffa’s, won an academy award for “channeling Hoffa’s rage.” Some daytime soap opera heartthrob whose name I can’t recall portrayed Bobby Kennedy, and Ernest Borgnine portrayed J. Edgar Hoover. In once fictionalized scene to make the FBI look tough, Brian Dennehy is almost bawling with fear of stepping into Hoffa’s lair agin, and the actor that portrayed Walter Sheridan, the head of a 500-agent Get Hoffa Task force that, until Saddam Hussein and Osama Bin Laden, was what journalists said was something like: “history’s most expensive and fruitless pursuit of one man by any government on Earth,” slapped Brian Dennehy.

If there’s one point I’d like to make: that never happened. Walter became a trusted NBC investigative journalist and died peacefully in 1996. He never told me what he thought of that scene in Blood Feud.

In another scene, Blake, as Hoffa, is standing in a room with Dennehy, as Big Daddy. The camera zooms in on Blake as he stares into space and thinks out loud, slowly mimicking tossing a bomb into Bobby Kennedy’s home. He describes using plastic explosives to kill Bobby and his family, and asks Big Daddy to get some from his contacts in the New Orleans mafia. Big Daddy refused, saying he wouldn’t kill kids; but, in real life and soon after that 1962 meeting, Big Daddy was arrested for kidnapping two small children on behalf of fellow Baton Rouge Teamster Sydney Simpson, who had lost them in custody court. In real-time, Hoffa then went on to describe a second, alternative plot: to find someone unattached to the Teamsters and give them a sniper rifle with a scope, and to shoot Bobby as he rode through some warm southern town that was overtly against of the Kennedy’s politics; a few months later, that’s how President Kenendy was shot and killed as he rode through Dallas, Texas, in his convertible and was presumably shot by Lee Harvey Oswald, a New Orleans Native who trained in the Baton Rouge civil air force under the alias Harvey Lee and knew Big Daddy well.

That kidnapping charge was the “minor domestic problem” that Hoffa sarcastically used “bunny ears” to describe how Bobby Kennedy and the FBI whitewashed my family’s history to protect their only witness keeping Hoffa in prison. It wouldn’t be until 1992 that President Bill Clinton released the first part of the classified 1976 John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Junior assassination report that Big Daddy also traded arms with Cuba’s dictator, Fidel Castro, and was a probably a person behind the scenes of President Kennedy’s assassination; by then, Hoffa’s puns about Big Daddy being an “all-American” hero were lost on people who didn’t remember history.

In 2019, sixty years after Kennedy’s death, Big Daddy was portrayed by the burly actor Craig Vincent in Martin Scorsese’s opus about Hoffa, “The Irishman,” based on a 2004 memoir called “I heard you paint houses,” by Charles Brandt and Frank “The Irishman” Sheeran, a mafia hitman, Teamsters leader, and colleague of Big Daddy’s who claims to killed Hoffa in a suburban Detroit home in 1975.

To paint houses was mafia lingo for coloring a wall red with splattered blood, and Hoffa’s Teamster story is intertwined with America’s mafia stories. Scorsese had raised $257 Million to make his film for entertainment, and hired all the best name actors, like Robert DeNiro, Al Pacino, Joe Pesci, and around a dozen more veteran actors known for bringing in audiences. Craig Vincent was chosen for a small role portraying Big Daddy; Craig is a 6’6″ Italian-American with a barrel chest, dark complexion. and northeastern tough-guy accent who had worked with Scorsese, Pacino, and Pesi in 1995’s Los Vegas mafia classic, Casio. To adapt to Craig’s accent and darker complexion, Scorsese changed Big Daddy to be “Big Eddie,” and, because the film was centered around “The Irishman,” around two chapters of Big Daddy’s role in “I heard you paint houses” was simplified or omitted.

Craig and I spoke when he was researching his role, because he wanted to know what personality traits allowed Big Daddy to fool Hoffa, the mafia, the supreme court, the Warren Commission, and probably all of the FBI; more specifically, what made a jury of peers believe Big Daddy over Jimmy Hoffa after only four hours of deliberation? I couldn’t answer concisely, but Craig and I chatted for an hour or two again over the next year, and I learned that his filmed 20 minutes would be edited down to only five minutes, because no one knew how to squeeze Big Daddy into an already whopping three hour and twenty nine minute epic packed with more known characters people wanted to see.

The Irishman sold out theaters the summer of 2019, but Covid-19 shuttered public spaces worldwide soon after. Netflix bought the rights and streamed The Irishman globally, and it set streaming records as almost a Billion people saw a simplified version of my grandfather’s part in history.

Craig’s question planted a seed in my mind that led to this memoir, and I spent the two years of Covid-19’s shutdown pondering how to answer the next time an epic film is made with Big Daddy in a small role. My mind kept going back to his Baton Rouge funeral on 11 March 1990, where I showed up with my two middle fingers still buddy-taped from being broken two weeks earlier. The New York Times and Los Angeles Times listed me as one of his surviving grandchildren; the only person who noticed my finger was Walter Sheridan, the former director of the FBI’s 500-agent Get Hoffa Task Force. A few months later, I was a paratrooper in the first Gulf war, Desert Shield and Desert Storm, and the year between when Hillary Clinton broke my finger and the final 15,000 pound bombs that ended the war is, to me, my strongest memories of who Big Daddy was and why it matters.

The Hillary who broke my finger was not Hillary Rodham Clinton, who became a household name when Arkansas governor William “Bill” Clinton became president in 1992; the Hillary that broke my finger was the returning three-time undefeated Louisiana state champion wrestler, captain of the revered Baton Rouge inner city Capital High School Lions, and winner of the 1990 Baton Rouge city tournament on 03 March 1990. He broke my finger in the first round and pinned me one minute and forty seconds into the second round, and the Louisiana High School Athletic Association website lists me as winning the silver medal.

Other than a few mentions when my grandfather was famous and I was a high school wrestler, I’m mostly offline. I’m the Jason Partin and Jason Ian Partin listed on a handful of patents on the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office website; all of my inventions are medical devices and implants to accelerate healing of small bones, like in the spine and the one in my finger that Hillary broke. A few web sites on military history mention me, and a few international magazines for magicians – the type with cards and coins and sleight of hand – mention me from roles I’ve served over the years. When Craig and I first spoke about his role as my grandfather, I was the Jason Partin on the University of San Diego’s Shiley-Marcos School of Engineering website as leading some engineering courses and managing their innovation program in a facility called Donald’s Garage, named after the mechanical engineer Donald Shiely; and I was the Jason Partin on the University of California San Diego’s website as advising their entrepreneurship program in The Basement, a similarly named program as Donald’s Garage and also meant to get student’s into hands-on learning rather than repeating what they learned in books.

I told Craig that the analogy of parroting books and him trying to learn Big Daddy’s character from history records was the same. To understand someone, you have to either become them or study the people who knew them well and see how they reacted. For Big Daddy, that would mean jumping into Jimmy Hoffa’s world, which included the mafia, and the Kennedys. Only a few people left alive can do that, and most of them are good at taking secrets to their graves.

To answer Craig’s question about Big Daddy, I’d have to begin with wrestling Hillary Clinton, and then go from there.

Go to the Table of Contents

- From “Hoffa: The Real Story,” his second autobiography, published a few months before he vanished in 1975 ↩︎