Chapter 1, I arrived in Khathmandu

I arrived in Kathmandu without a computer, phone, or hotel reservation. My goal was to spend three months offline, immersed in new experiences. I’d complete my journey by returning to my home in San Diego, and deciding whether or not to have surgery.

If I decided to get spinal surgery, surgeons would fuse a few of my cervical vertebra together with metal plates, and possible a few of my lumbar vertebra with metal rods and intervertebral spacers. If I got the surgery, there would be a 60 to 70% chance it would reduce chronic pain I had felt for over a decade, but a 30% chance that I would not benefit, and a slight chance I’d increase my suffering. The surgery was risky, and could lead to accelerated spinal degeneration and a lifetime of needing more surgeries. I wanted to clear my mind before making such an important decision.

Not moving hurts me more than moving, because inflammation accumulates, and muscles tighten and compress damaged spinal discs between vertebra, and that compresses nerves that radiate pain to my arms and legs and head. The flight from San Diego to Kathmandu had taken 26 hours, and I was in so much pain when I go off the plane that I knew nothing short of a life-or-death situation would get me back on a plane home.

I had read once that the good thing about a life or death situation was that it’s over quickly. That’s been true for most of my life or death situations, but now that I was past middle-age, my life or death situations unfolded slowly. The next three months would determine how long I lived, and the quality of that life. To me, this journey was a life or death situation.

When I was a soldier, life or death situations were intense bursts of machine gun fire and close-up combat that lasted less than a few hours. Now, life or death battles come in the form of clogged arteries from too many eggs at breakfast, a weakened liver from too much beer, and, ironically, deteriorated mental functions from too many pain medications.

I had been taking prescription opiods for almost four years, and had stopped a year before arriving to Kathmandhu. If I were going to make an important decision, I wanted my choice to stem from a clear mind.

At the Kathmandhu airport, I doubted the wisdom of choices that led me there. At that moment, I was too distracted by pain to enjoy the idea of traveling. But there was no way I would get on another plane until I felt better. I tried to make myself smile by imagining a three month trip turning into a lifetime of living in Kathmandu, simply because I would never sit still again, and I couldn’t walk half way across the planet to get back home.

I waited in line with a few other tourists to pick up our bags and get our passports stamped. I was uncharacteristically grumpy because of my headache and pain from degenerated spinal discs, and I was upset to discover that my backpack had been opened, and that some of my hiking gear was missing. The trekking poles were nice, and I’d miss them – they were lightweight carbon fiber, and telescoped into small and portable pieces for when I was walking through towns rather than over mountains.

I couldn’t reasonably hike without trekking poles, or at least a walking stick or cane. Ten years prior, three independent surgery centers told me that if I didn’t have both of my hips replaced by medical implants, the ones made from metals and plastics, I wouldn’t be able to walk within three years. I would decide whether or not to have hip replacement surgery, in addition to spine surgery, when I flew out of Delhi in three months.

I tightened my backpack straps, and tried to focus on any thought other than my missing trekking poles, or the pain in my head, neck, back, hips, knees, ankle, wrists, and finger.

The finger was the worse; it was broken for the first time when I was 15 years old, and for 30 years it seemed to get reinjured again and again. After the flight, I had to open and close my fist a few times to relax the swollen joint. The pain wasn’t bad, but it reminded me that past injuries stay with us for the rest of our lives, and that the choice I’d make in three months would affect my future self in the same way that my choices at 15 were affecting me now.

As I waited in line, I distracted my mind by opening my Lonely Planet travel guide book for Nepal, and flipping to the chapter for recommendations of where to stay in Kathmandu. Most people would use their smart phone, or have made reservations before arriving, but I wanted to be offline, and I enjoyed using guide books. Lonely Planet and Let’s Go had been my trusted guides for 30 years, and I felt my body relax as old memories sparked positive associations. I felt the weight of a book and smelled the new paper, and apprecaited how books stimulate all of my senses.

Nothing digital comes close, and I’m always happy to leave my smart phone at home when I travel. I compromised on this trip, and brought my phone for emergencies, but I didn’t get the travel upgrade, and any calls would cost so much that practical finances would prevent me from using it mindlessly.

I moved forward in line, and pushed my backpack forward with one foot as I read The Lonely Planet for Nepal. It looked like I’d have fun, but at that moment I could only focus on the next step, which was getting a comfortable place to stretch and relax, and finding somewhere to enjoy a Nepali beer.

I splurged on a nice hotel, one with a jacuzzi and breakfast room, and spent two days reading about Nepal, practicing yoga, and exploring around the hotel. I sampled a few local beers. They were good. But, I was spoiled because I had come from San Diego, the self-proclaimed Beer Capital of the America, with more micro-breweries per capita than any other city. The year before, San Diego breweries had won 535 out of 2,000 medals at the Great American Beer Festival. As I mentioned, now that I’m older, life or death choices happen more slowly; at least I wouldn’t have too many eggs in Nepal, nor would I have access to opiods.

After two days, I felt coherent enough to find a new place to stay and begin my journey. I found a monestary a few miles uphill from my hotel, near a 2,000 year old temple overlooking the city. To this day, I can’t pronounce the temple, Swayambhunatha, a World Heritage Site overlooking Kathmandu Valley, and the now smog-chocked city of 2 million people honking horns and rushing to and from work. The monestary was a peaceful refuge, and met the criteria I sought.

Thibetan refugees had fled China 50 years before, and Buddhist monks created Benchen Phuntsok Dargyeling Monastery, a 10 minute walk from Swayambhuntatha. They built a guest house attached to the monks’ living quarters, and called it Benchen Vihar Guest House. I stayed there for 8 U.S. dollars U.S. per night; the monks used proceeds to support a free medical clinic for anyone in need. Originally, they created the clinic for Thibetan refugees who were crossing the Himalayas from what was once Tibet to Kathmandu, and now they serve anyone in need.

“Watch out for the monkeys,” said the monk who showed me my room. “They will steal anything you leave out, and some have attacked and bitten tourists.” As if part of a rehearsed skit, a large monkey jumped from the roof and landed on the communal picnic table near my room, and growled at us.

“Get!” shouted the monk. The monkey barred his teeth and raised an arm to show us how big he was. The monk picked up a rock and threw it at him, hitting the monkey in the chest, and sending him scurrying back up to the roof over my room

“I hate them,” the monk stated as a matter of fact, dispelling my preconceived notion of monks being peaceful.

“This is my job,” he would tell me a few days later. “I used to sell Buddha statues to tourists. I made a little money, but not much. Tourists stopped coming because of the war and earthquake, and I had no way to earn my livelihood, so I became a monk. It’s not a bad job. I have to wear a robe, and practice prayers every morning, and show tourists like you the guest house. I have enough to eat, friends, and medicine. I get to practice speaking English. No one is trying to kill me. It’s a good job. All I have to do is maintain the precepts, and practice doing no harm.”

The precepts included not drinking beer, and refraining from sex outside of marriage. That sounded horrible to me, which is one of many reasons that I earned my livelihood as an engineer and a teacher instead of a monk.

The room he had shown me was as comfortable as budget rooms in The Lonely Planet, but it was far removed from Kathmandhu. The Lonely Planet didn’t even list the monestary as in Kathmandu; it was under their “Elsewhere” category, which is where I wanted to be to make my first decision.

I wanted to hike across the Himalaya Mountains, to follow one of the trade routes between Kathmandhu and what used to be Tibet. These routes were narrow foot paths that snaked up and over the world’s highest mountains, and for at least a thousand years traders from the Thibetan plateau had led teams of yaks burdened with wool into Kathmandhu, and returned with spices and foods from the fertile Kathmandhu valley.

You could spend weeks on one trail. I read in the Lonely Planet that the Annapurna trail was popular with tourists because it went across the Himalayas, and once over the top you could continue walking to Tibet, or continue in Nepal and end back up where you began.

Approximately 100,000 people start hiking the Annapurna circuit every year, but not all complete the circle. Most of those who don’t complete the loop will turn back because of fatigue, altitude sickness, or being unprepared: the trail crosses Thorong Pass, one of the world’s highest, and it is a barren, windswept, frozen trail for the final week of hiking. It’s not an easy hike; most people find it challenging.

Unfortunately, some do not live to complete their hero’s journey. Three years before I arrived, 500 tourists and guides were trapped in a surprise snowstorm near Thorong Pass. 32 of them died in the weeks it took mule teams to dig through the snow and reach them.

Many more suffered frostbite, and lost fingers, toes, and limbs. They had expected clear weather, because they were hiking in peak tourist season, but an unexpected storm brewed in the Indian Ocean and pushed moisture up the mountains. That moisture quickly became clouds, and snow, the trail became blocked in both directions.

I was at the very end of the hiking season, just before winter, because I wanted to immerse in the culture of Nepal without distractions from crowds of tourists.

Nepal was coming out of a 10 year civil war. 180,000 people had died or disappeared. Then, in 2016, an earthquake devastated Kathmandhu Valley, killing 10,000 more. Almost all of Kathmandhu had been devastated, and ancient temples had been reduced to piles of rubble. Tourism had plummeted, and people were desperate to earn a living.

I hadn’t known any of this when I bought my airplane ticket. In any capitalist culture, supply and demand dictate prices, and not many people wanted to spend their vacations hiking over a dangerous mountain, in a war zone, in a poor country, with minimal infrastructure because of an earthquake. Less demand meant more supply of plane seats, and cheaper tickets; it’s a classic case of cause and effect, and studied in almost any economics class.

I had bought my airplane ticket on an impulse because it was inexpensive, and seemed like an opportunity to enjoy one last mountain hike before I made my decision on whether or not to get surgery on my spine and hips.

I spent a week at Benchen Guest House, borrowing books from their library, meditating and throwing rocks at monkeys that tried to steal food and books from the picnic table. I chatted with the monks, and hung out in their medical clinic to see if I could be useful, and ate at their vegetarian restaurant; it was delicious, and offered to the community at a low cost so that anyone could have healthy food. I realized they were creating a process of improvement: healthier food now, meant less need for healthcare later. And if they had less expenses for their medical clinic, they could invest more into their restaurant.

“Maybe one day you could build a refuge for the monkeys,” I told the monk from my first day, smiling at my joke.

“I hate them,” he replied.

He didn’t understand my humor – sarcasm is not universally understood, and is a bad habit that takes me a week or two to change when I travel. He seemed genuinely upset to be reminded about the monkies that made his job more difficult, so I changed the subject and invited him to throw a Frisbee.

“A what?” he asked. I showed him the plastic disc that I called a Frisbee. He wasn’t interested, and didn’t seem like chatting, so I threw the Frisbee by myself for a while; it helps reduce inflammation in my arthritic shoulders, and keeps my ligamtments active in their full range of motion. Hopefully, moderate exercise every day would allow me to maintain my quality of life as I get older. My choice of surgery was really a choice about the life I wanted to live in my retirement, and I hoped that future would include playing games with grandchildren.

On my second to last day, I carried the Frisbee, a few snacks, and a book in my backpack, and hiked to the top of Swayambhunatha. I hoped I could find it without having to ask directions; I couldn’t pronounce “Swayambhunatha,” and most locals who saw me assumed I wanted directions back to the tourist hotels in the city center. I walked silently, avoiding people who kept directing me elsewhere, until I found the trailhead at the base of the mountain below Swayambhunatha.

I did not find the trail by skill, nor by luck, but by the dozens of vendors selling Buddhist statues to tourists from push-carts at the base of the trail. When they saw me, they let me know exactly where I should be, and that place was at their carts, buying a Good Luck Buddha. I thought about the monk at my guest house, and smiled imagining his career change.

I declined politely, and walked past other carts that sold snacks to Nepali pilgrims who hike to the temple for spiritual pursuits and exercise, and stalls that sold idols, flags, incense, and other spiritual and regligious items, similar to how Catholics light candles and pray to statues of their saints. Swayambhunatha is a holy site for many Buddhist and Hindu pilgrims, and I learned that many of them called it “The Monkey Temple.”

I liked that; I could pronounce it, and I’d probably remember it.

I joined a few pilgrims making the steep hike up to the temple, trying to ignore the hundreds of monkeys who followed us and kept trying to grab food from our bags. I already felt annoyed, and I could see why my monk friend grew to loathe them. I would try to ignore them, and focus on my goal of climbing to The Monkey Temple.

I reached the temple, and was rewarded for the effort as soon as I walked through the 2,6000 year old stone gates. The temple was holy. Loving care had been put into every detail, and I paused to admire the seamless flow of tourists passing through the gates and walking clockwise around the pagoda, the rounded temple typical of Buddhist shrines.

They walked quietly, and reached out with one hand and spun prayer wheels attached to the pagoda. Many pilgrims carried small prayer wheels in their left hands, and spun those clockwise, too. Inside of each prayer wheel was a prayer, or a meditation, that was intended to calm the pilgrims and add positivity to the world. They believed their combined clockwise motions – the pilgrims, their prayer wheels, and the pagoda’s prayer wheels – were part of the path to spiritual enlightenment, and to the peace and enlightenment of all humans, because all humans are from the same source.

An elderly monk saw me observing the process. He smiled and pointed to a metal object held by concrete between two stones, and he said, “The Method,” in a way that told me he didn’t know many other English words. He pulled his hand back to his lap, and continued smiling.

A boy who had been playing in the shade behind him walked over and looked at me curiously. I waved, and he waved back enthusiastically. I knew they’d like to practice English, and that I’d like to learn more about “The Method,” so I reached into my backpack and removed a few pieces of fruit, and offered to share with the boy and the monk. They motioned for me to sit and join them, and we ate our fruit. The boy accepted half of a cookie I had brought, but the monk politely declined. I ate my half of the cookie, then we sat in silence for about ten minutes.

“The Method,” he repeated, pointing to the object. It was a chankra, a weapon of knowledge. Chankras are one of the oldest religious symbols in the human story, dating to before written history, and has been adapted by Hindus and Buddhists as a way to teach enlightenment without a lot of words. It was the weapon of Indra, one of the first gods we know of, and his weapon was a tool to give humans knowledge. In a way, Indra was like the Greek god Prometheus, who gave humans fire, except that Indra’s knowledge was rooted unifying all humans peacefully.

“The Method!” He leaned back, and smiled calmly. I hoped he knew more words in English, but I was having fun regardless. I knew about Chankras, and that the one in front of us had eight prongs representing the method, the path to follow, and the way to enlightenment. It was similar to the Catholic Ten Commandments, but with less ambiguity.

According to The Buddha, the eightfold path is: Right Action (don’t harm others with your actions), Right Speech (don’t harm others with harsh words, lies, or gossip), Right Livelihood (don’t earn your living making or selling things that harm others), Right Mindfulness (be aware of your mind’s reaction to the five physical senses, and your mind and body’s reaction to the sixth sense of thoughts, ideas, and imagination), Right Concentration (do not get lost in thought and forget to be mindful; do not become attached to transient thoughts and reactions that pull you from the present moment), Right Effort (begin with the intention to do no harm, and to end all suffering, and to be happy and help others be happy; and follow through with the daily practice to remain mindful and present in each moment), Right Understanding (continuously improve your wisdom based on what you experience and know to be wholesome), and Right View (see the world for what it really is: a series of effects and their causes, and that our words and actions have ripple effects on our happiness and the happiness of others). According to the Buddha, if you follow the Eightfold Path, you’ll find joy and happiness here on Earth, now, at this moment. He was human and had done it, and gave away his method for all of humanity to practice, if they wanted to.

I wanted to hear what this old monk, and the little boy, felt about The Method, and I wanted to let them practice their English, and I wanted to begin learning Nepali, so I spent the next hour or two in a conversation. I used common Nepali phrases, conveniently written in my Lonely Planet guide book, and we had the best day of my trip so far. My pain was subsiding, and I was beginning to get into the flow of traveling and learning from people.

The boy and I took a break from practicing English and Nepali, and we threw my Frisbee for about 30 minutes. He learned quickly – faster than I learned Nepali – and we sat back down with the elderly monk to listen to more about The Method.

The monk’s English improved by a word or two, and the boy seemed to have learned entire sentences, but I still couldn’t pronounce “Swayambhunatha.” It’s funny; I was a “communications laison” between 17 countries once, yet I have no natural skillset for speaking different languages. Fortunately, I’ve been a good listener, and my method of communicating had worked for me for 30 years; it usually involves sharing food and playing, and it had worked that day.

I left my teachers, and explored The Monkey Temple for a couple of hours. It was worth the effort. I hope you can visit one day; my words would not do it justice.

After exploring the temple, I wanted to relax and read a book for a while. I sought a quiet spot, free from people trying to sell me Buddhist statues, and free from monkeys trying to steel my backpack. I found a footpath leading into the forest below the temple, and followed it for ten or fifteen minutes until I found a clearing with a view of the smog hiding Kathmandhu.

The ground was damp, so I sat on my Frisbee and meditated for a few minutes. Slowly, I began to relax. My mind drifted to the improbability of me being there at that moment. It had been two weeks since I had spoke with my doctor in San Diego about this trip, and already it seemed like a lifetime ago.

I had been in so much pain for a month leading up to my flight that I scheduled an extra 15 minute time slot with my primary care physician at the Veterans Administration Hospital, Dr. Shaw. He obliged, and we had 30 minutes to go over last-minute concerns. A few months before, he had gone over my medical records – I have almost 30 years of medical history on file with the V.A., going back to when I was 17 years old – and made sure I wouldn’t put myself in unnecessary risk. We took blood samples, x-rays, MRI’s, and CT scans to compare progress of my diseasses from a few years before, and he suggested vaccinations to protect me from the diseases of developing countries.

Dr. Shaw was from India. He knew the risks. More importantly, he cared about his patients, and treated them as individuals rather than applying statsitcs-driven medine, as much as the beurocratic V.A. system would allow. We had known each other for almost ten years; he, too, was a hiker, and had taken his children to India a few years before so that they could see the difference between where he grew up and San Diego, where they had been born and raised.

“Great to see you, man!” he said when he walked into the room where I was waiting. We slapped hands in a rhythm that was somewhere between a handshake and a ritual between old friends. “What brings you back so soon?” I had been there only three months before, and wasn’t scheduled to return until after my trip, when I’d decide on surgery.

“I fucking hurt,” I said. It was the first time in many years that I began our conversation by talking about pain; I’d rather talk about hiking or books with Dr. Shaw before we looked at my test results. But, this time, I was in so much pain that I couldn’t be polite. He saw that, and leaned forward, concerned, and we talked about what was going on in my mind.

“What’s going on,” he said in a more somber tone than he had greeted me. He wanted to listen to me, to understand what I meant by “I fucking hurt,” which means different things to different people.

The mandatory “pain scale” used by the V.A. asks you to rate your pain on a scale from 1 to 10, with 1 being almost imperceivable, either drowned by normal sensations throughout each day, or a minor inconvenience, like an ant bite. A pain level of 10 is defined as the most pain you’ve ever experienced in your life. That’s ridiculous, because it tries to equate a “6” between two different people who may have had different experiences in life, or who have different pain thresholds.

A middle aged woman who has experienced childbirth and broken bones may have a different definition of “6” than a young man with soft hands, born into wealth, who’s “10” may have been a hangover the morning after drinking too many beers. And, what does a “6” mean when you’ve felt a “6” every day for almost 20 years? Is your 6 now your baseline, a permanent floor to base future pain? Or, does your scale remain the same, and on the rare days where your pain subsides to a “5,” and though someone else may not want to experience a 5, you feel it’s like a gift from God, giving you repreive, and a chance to refocus before the 6 returns tomorrow.

When I first met one of the V.A. nurses, they asked my pain level. I wanted to give them my scale, rather than a number they would associate with their own experiences. At the time, my worse hangover was a 2 or 3, but that’s not a universal measurement, either, so I asked them if I could describe my “9.” They said yes, and I described it as I pointed to the scars, and adapted the words and timing of my story based on their reactions. I wanted to ensure she understood, more than I wanted to tell my story. I could tell by her raised eyebrows and look of surprise that they may understand, then said I felt a “6” that day. They said, “Dear God! I’ll get a doctor!”

I can no longer remember my baseline, but I know that I had been feeling a 6 for a month leading up to my fight to Kathmandu. Then, for two weeks, I felt a 7 every day. I was on the verge of an 8, and was concerned that something new was happening in my body. I wanted an emotionally detached observer to go over my recent test results. Dr. Shaw obliged, and was kind enough to add an extra 15 minute time slot to my visit.

Of course, he knew it was riduculous to gain insight on anyone’s health and well being in 15 minute time slots, which is why we worked well together. We were both in on the joke, and it was more fun to laugh than to cry. To paraphrase Kurt Vonnegut, there are two choices when reacting to pain or bureaucracy, tears or laughter, and I prefer laughter because there’s less cleaning up to do after.

We went over my records and recent test results, and looked at x-rays MRI’s from several years ago to compare to more recent ones. Nothing was remarkable, and we had 10 minutes remaining. That’s when I told him what was really bothering me: my memory had been slipping, I thought.

He sat up, alert, and pressed for details. I told him that it was subtle, and may be in my imagination, but one incident bothered me. I was working on a home project that used simple math, and I couldn’t remember what you get when you multiplied 6 times 7. That moment was remarkable, not because of the simple math, but because the answer is 42, which is the answer to Life, The Universe, and Everything in my favorite science fiction book, The Hitchiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

Dr. Shaw and I laughed about that for a moment – he had read the book, too. The nonsensical answer to Life, The Universe, and Everything was a joke, but I didn’t laugh when I couldn’t remember that 6 times 7 was 42. Dr. Shaw took it seriously, too.

We scheduled some tests, and noted our concern in my record. If he left the V.A., and I had to get another doctor, his record would allow me to continue treatments seamlessly rather than starting a new relationship 15 minutes at a time.

He looked at test results from my blood samples from the day before, and said, “You’ve tested positive for marijuana again. It can cause short term memory loss. And, the V.A. wants me to tell you that it’s an illegal drug.”

“I’m sorry,” I said with mock humility, “I forgot what we were talking about.” We laughed, and when I saw him relax and sit back in his chair I said, “I know. But this isn’t that; this was a gaping hole in something I should have known mindlessly. I spent at least a minute trying to see the answer, and when I realized the answer was 42 I became alarmed.”

I paused, and looked down. My cheeks trembled, and my eyes watered a tiny bit. Dr. Shaw didn’t say anything. He waited patiently for me to continue when I chose to.

“I stopped smoking, and started observing my mind for lapses in memory. It happened once again, with a name I should have easily known. It may have been happening before, but could have blended in with things like forgetting where I put my keys or eyeglasses, typical lapses when you get older and have more things on your mind. But this was forgetting the answer to Life, The Universe, and Everything. I’m concerned.” I could have said, “I’m scared,” or “I’m terrified,” but by saying “I’m concerned,” I was focusing on what was within my control, and what I should do about it.

We talked about options, then laughed about how the V.A. considers marijuana an illegal drug, yet for ten years they had been prescribing me opiods, one of the most addictive drugs on Earth. He knew the irony, and we had discussed that when I asked him to add to my medical records that I was to never be prescribed opiods again, no matter what I said in the future. I wanted to ensure that opiods were no were no longer an option for me to deal with pain.

He asked about my alcohol consumption, and I told him I was down to one or two glasses of beer, two or three times a week, and we both knew that was well below the V.A.’s threshold of concern. He noted the number of beers on the V.A.’s mandatory questionaire, then laughed about how the “two beer” limit was from old information, when a beer was defined as 12 ounces of 3.5% alcohol malted beverage.

Today, in San Diego, our typical beers are 8% India Pale Ales, in 16 ounce pours. One of my beers equaled four beers on the V.A. questionnaire, which meant I had consumed 8 beers, according to the V.A.’s intention, but their beauracracy wasn’t quick to improve as the beer culture changed.

Dr. Shaw was wise enough to know that good healthcare is impossible with questionnaires, that people are individuals and not statistics. He took time to know me as a person before recommending healthcare options. We had even recommended books to each other that helped us empathize with our different upbringings, and I trusted his opinion more than the output of a V.A. computer program. He had nothing more to add to my trip, but noted my memory concerns, in case I forgot to tell him next time.

We had five minutes left, and we talked about his last trip to India, and which books I’d bring on my trip. I told him “Siddhartha,” by Herman Hesse, which is what I was reading two weeks later at the top of The Monkey Temple, trying meditation instead of opiods to reduce my pain, so that I would have a clear mind to choose whether or not to have metal rods permanently placed along my spine, and metal joints placed in both hips.

Siddhartha is a novella that won Hesse the Nobel Prize 80 years before. It’s the story of a young man in India, Siddhartha, a on his journey through every experience and emotion in the human condition. Though it was set 2,500 years ago, human emotions and struggles are the same. Herman Hesse had concisely tapped into the truth of human existence in a few thousand words, and I didn’t realize I was crying until my tears dripped on the final few pages of the book. Even the monkeys around me seemed calm, as if they could sense and share the strength of my emotions that stemmed from me reading Siddhartha’s journey.

I closed the book, and I knew I’d leave for Annapurna in the morning. I said goodbye toe the monkeys, and they barred their teeth and tried to steal my backpack as I stood up. I can see why even monks grow to despise them.

I walked back down the steps and past the Buddhist statues, and gave the remaining half of my lunch to one of the dozens of beggars surrounding the food stalls, and, miraculously, I found my way back to Benchen. I didn’t want to ask directions, because I couldn’t remember it’s name; not from a memory lapse, but because I’ve always been slow to remember new words.

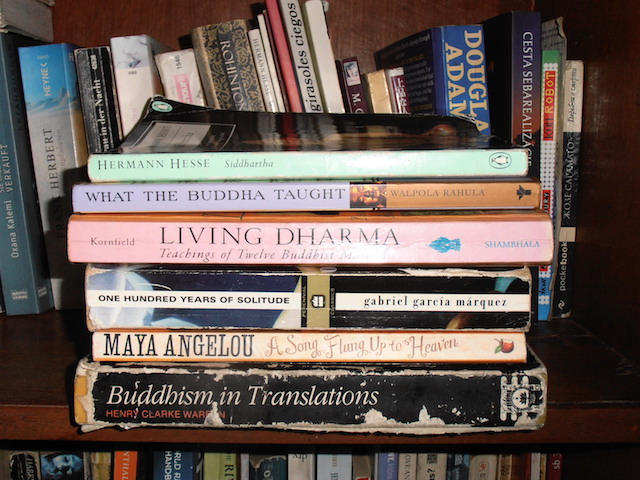

I packed my big backpack, and returned the books I had borrowed from the monks library. I added the books I had brought from San Diego to their guest library, part of a common trend in backpacking destinations to take a book, or leave a book, and that process is one of my favorite ways to share books with strangers. I left Siddhartha, Maya Angelou’s “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings,” and “One Hundred Years of Solitude.”

I looked for a book to take. I saw at least six copies of Siddhartha in different languages; dozens of books on Budhhism, meditaion, Hinduism; and a few on social justice and global economics. Suddenly, I laughed so loudly – it was more like a ‘snort!” followed by chuckling – because I saw a copy of Douglas Adams’s “The Hitchiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.”

The copy at the monestary was a later edition, and had all five books in one binding. Adams called it a five part trilogy, and I couldn’t imagine a better ending to my stay at Benchen Guest House than to pick up the Hitchiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, to feel it in my hands, and to read the only advice it gives to anyone on a journey to the unknown: Don’t Panic.

I didn’t need another book yet, because I still had a few unread in my backpack, and I returned to my room and slept peacefully to the sound of monkeys howling.

At 6am the next morning, I woke up, practiced yoga for twenty or thirty minutes, used the bathroom, and took an extra long hot shower because I knew it could be my last hot shower for a month. I left my key in the door, and shut the door to prevent monkeys from entering; they may have opposable thumbs, like us, but they haven’t mastered opening doors. Yet.

I left Benchen Monestary and began walking down the road until a taxi stopped. I read my Lonely Planet and somehow pronounced “The bus station, please,” and thirty minutes later I was purchasing a ticket to a town eight hours away.

I joined a group of Nepali’s on a bus designed for someone several inches shorter than I am, and six cramped and bumpy hours later the bus driver let me off by a nondescript bridge along the dirt road, adjacent to the Annapurna Circuit trailhead. I watched the bus drive away, tried to loosen my neck and relax my hips with a few quick yoga poses, and began walking uphill.

Return to the Table of Contents.