Annapurna and Bodh Gaya.

I learned more than I can say with words at a Thibetan Monastery in Nepal. I was in Kathmandhu teaching magic to a group of school kids who had lost their school building during an earthquake. The quake had killed more than 10,000 people, and happened as they were recovering from a decade long civil war that had killed dozens of thousands more.

They learned quickly, as kids do when they’re having fun and have seen how to work well as a team. They practiced in the 2,500 year old plaza in front of where their school had been. Almost half of the buildings had not been repaired. Rocks and bricks and lumber littered the plaza.

We laughed and they begged to learn more, and I tried to teach them how to learn anything they wanted, and to choose how they earned their living. They were lucky, and were relatively wealthy; their private school gave them access to the internet, and allowed them time for extracurricular activities with visitors from other countries.

We finished the day. I gave them the Nepali coins I had used to teach coin tricks, and walked back to the Monastery.

I was renting a simple room with a private toilet and hot water for $8 a night. The monks used that money to help operate a healthcare clinic free to anyone. It was their job, and a few told me it was better than not having a job. They had to wear robes, own nothing extravagent, and wish people happiness. In exchange, they were given room, board, a community, access to healthcare, a free library, and freedom to make their own choices.

One of the monks told me that before he was a monk he sold Buddha statues to tourists, and that now he earns his livelihood as a monk. Not as many tourists came Kathmandhu after the war and earthquake, and that even in the best of times there were too many kids selling Buddha statues to tourists. I did not know how to answer when he asked how I earned my livelihood; my plane ticket had cost more than he would likely earn in a lifetime of selling Buddha statues.

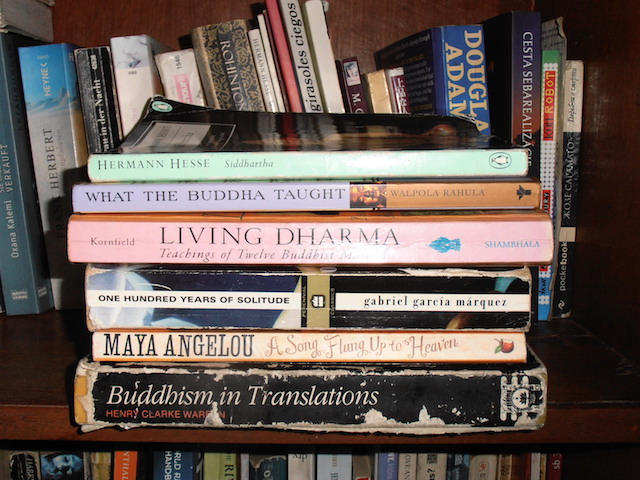

I had free access to their library. I read at least a dozen of their books, and the few I had brought books with me. There was a book exchange on a bookshelf in the hallway that connected the library with guest rooms. It contained at least 200 books, and about half were printed in English. Twenty to thirty in Sanskrit or Pali, and the remainder were in various countries from around the world. There were no picture books on how to become enlightened.

I smiled and thought that becoming enlightened was more likely if you read English and had a free library at your fingertips. And these 200 books. And a community to exchange them. And free time, without concern for a safe place to sleep and enough food to eat. I was fortunate, yet I’m not enlightened. For me, nirvana would more than just reading and writing about it.

I left the library and carried a book to the top of the Buddhist temple that had overlooked Kathmandu for 1,500 years. I read Siddhartha by Herman Hesse in one sitting. It’s a short book.

I didn’t notice I had been crying until the final few chapters , when tears that had collected on my cheeks dripped onto the book. I looked up, saw the city disappear behind dark smog, and looked back down at my watch. Three and a half hours had passed. I finished the book and walked down the mountain and shared my lunch, then walked through the city and back to the monestery.

I went to my room and lightened my backpack by removing books I had brought. I walked to the book exchange, and left 100 Years of Solitude, a copy of I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, a 1971 literary memoir set near where I grew up, and several books by and about Buddhist meditation masters.

I saw that someone from some another place and time had left a copy of a book that always made me smile, The Hitchiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. It gives you the answer to Life, the Universe, and Everything; but not the question. I laughed out loud, and turned my head sideways to read its edition. Douglas Adams made me smile every time.

The next morning, I took a bus seven or eight hours to the beginning of the Annapurna trail and began walking uphill. I carried four books in my backpack: The Lonely Planet Guide to Nepal, The Lonely Planet Guide to India (it was big, and heavy), What the Buddha Taught by Walpola Rahula, and the Tao Te Ching. I had a deck of poker playing cards, four well worn U.S. half dollar coins, and a Frisbee; a water purifier, and enough clothes to survive at least two sub-freezing nights at high altitude.

I always carried a Leatherman pocket tool with a knife, and I had enough cash to live comfortably for months in Nepal if I wanted to, and enough in a bank account to live comfortably indefinitely. All of my life’s work had been done.

Crossing Thorang-La pass on the Annapurna circuit trail was challenging. The route is thousands of years old, and lined with symbolism and small temples and prayer flags to help people stay in the present moment, to not worry about the future or dwell on the past. It takes focus to hike the entire circuit, up one side of the Himalaya Mountains and down another. Many other people have done it, and many more will. Three years before, 32 people had died at the pass after a surprise snow storm. It took mule teams weeks to reach them.

I almost died on the day I crossed the pass. My body was in more pain than I can describe; my vision was blurred on the periphery, and I had to focus on the center to watch where I stepped. My breath wheezed in and out of asthmatic lungs in thin air.

I could feel stiff stainless steel bone screws in my ankle digging holes into the softer cancellous bone they held together. The screws did a little damage every day, and I did not take enough time to let my bones rest and rebuild. To do that I would have needed more time on my Nepali visa and youth. I didn’t not think that would happen, but I could understand how people would pursue it.

I had not slept or eaten in two nights. I had read about worse situations. I had seen worse and everything’s fine, so I wasn’t worried. I could not sleep because I had mild altitude sickness. I had been above 3,000 meters for too long.

Thorang-La Pass is 5,416 meters, and the path is downhill from there. I was alone in a small rock shelter at 4,800 meters the morning of my last day, my pulse was down from 120 beats per minute to 82, more than my typical 50 to 54 range. I was fine.

I hadn’t been taking pain medications so that I could watch my body like a doctor who needs unfiltered access to how I felt. My body was ready to summit. All that had to be done was done. I began walking.

Eight hours passed very slowly yet also instantly. I reached the highest point and saw a sign that said:

THORANG-LA PASS

5416 mtr.

CONGRATULATION FOR THE SUCCESS

Among other things.

I took off my backpack, sipped water from a water bottle I had carried around the world, crossed my legs, and meditated for twenty or thirty minutes. I still felt like crap.

A man I had seen a few times took my photo, and I took his. He began walking down, and I limped around, hoping someone wanted to throw a Frisbee. That’s when I noticed that someone had severe altitude sickness, and would likely die if we didn’t get them off the mountain soon.

One person had a satellite phone, and had gone to find a clearing with enough space. The three people remaining were waiting for him.

She was a woman, and her husband held her, waiting. They leaned against a small rock hut, where a man boiled water for tea. I paid him a few coins worth $1.50 in the United States.

I helped keep her calm while we prepared for a helicopter rescue; at 5416 meters, that is very unlikely, and dangerous. No two of our group of six people spoke the same language. We were there four hours. I do not know how I remembered to set up a helicopter landing pad, or how I remembered to tell jokes while checking a pulse, or that I remembered how to communicate intention when you don’t speak the same languages, but I watched myself doing it. They flew away, I remained. I read that the helicopter ride would cost more than $10,000 U.S. I do not know if she survived, or if her husband remembers the Nepali man who made us tea while she was unconscious and we waited.

I helped set up an emergency helicopter landing zone, with rocks placed to indicate wind and hill angles. The helicopter came, imperfectly in the thin air. We carried her to the helicopter and everyone but the man who made tea and I left.

I walked down the mountain for a few hours until I felt my headache begin to dissipate and my heart rate return to under 80 beats per minute. I sat, cross legged on a rock overlooking a valley where wind channels air into earth and rock cliffs that tumble down onto waterfalls and fire from natural gas vents. People have worshiped that spot since before we knew how to record experiences by writing words.

I knew I should eat something. I had been vomiting for a few days, but believed I could eat something and that I should.

I unwrapped a Snickers candy bar I had put it in my pocket so that it would not be frozen – the temperature had been below freezing for several days, and the first snow of winter was beginning to fall.

I bit through a layer of cold sweet chocolate, into guey caramel, and crunched through a salty peanut, as the peanut fragments began to separate my life changed. I do not know how to describe it. I finished the Snickers and hiked down the mountain trail.

Two days later, I hiked through rainfall that obscured the snow capped moutains I had summited and entered the Kingdom of Mustang without a permit. My life has not been the same since. I can describe what that looks like to me.

Things began to change quickly. I was not worried.

I left the mountains, hiked through a jungle, and traveled across Nepal to where I believe Siddhartha Gautama had been born. I stood among the foundation of the eastern gate of a city that I believed to have been his, and I looked across the flat grassland and muddy rivers where I know he had stared, and left his family.

I ate lunch, and did not see more than five people in the two hours I sat there. I walked back to where a tuk-tuk driver was waiting.

He took me to the small towns near the city, showed me a small hill with a 2,600 year old rock foundation. It had sections that looked as if they could hold wooden posts that would provide walls and a roof, and I believed it had been a house or a temple built lovingly.

I believed that Siddhartha had returned to that house after leaving his city, and for the first time in seven years spoke to the son and wife he had left.

People no longer called him Siddhartha. Kings and kingdoms called him The Enlightened One. He was a teacher of a method to end suffering. He never claimed to be anything other than a human, and that his method was clear, unambiguous, and easy to understand. I wondered what the Buddha said to his son. Two days later, I crossed the border into India, where the Buddha died after teaching a way for 45 years. I believe the last words he spoke were: Practice your goal with diligence.

I crossed into India, and instantly poor crippled men drug their legless bodies across a dirt road to beg at my feet, and dirty children mobbed around me with hands outreached begging for food or money or acknowledgement. I began learning more.

A month later, after experiences that would not add to this story, I was meditating near a 2,000 old tree where 125,000 monks had gathered. Behind it was a towering stone temple. Everything was free. Many children and grown men sold Buddha statues to tourists.

I was invited to a conference on Philosophy of the Mind and Modern Physics at the Thibetan University during their 50th anniversary. I had to wait for a security clearance because the Dali Lama would be there – he had spearheaded the University in India after his homeland ceased being Tibet and dozens of thousands of people deserved a free education. As you enter the courtyard, you saw a sign:

Do not dwell in the past,

Do not dream of the future.

Concentrate the mind on the present moment.

395 w.f.c. (Buddha)

He laughed often, and spoke of the wisdom of unity.

He, too, knew about the challenges to our shared environment, and the need to work together as a united people on Earth.

I left two days early, and spent more time across from the hill where the Buddha first spoke. I laughed with Deepak and bought books from his push cart for two weeks. He had earned his livelihood and raised a family with his push cart for 35 years. He could only select a few books, and he happily shared his favorites. He invited me to meet his family, and gave me a hand painted Buddha statue to take home. I made room in my backpack, and went home a month later.

I have not taken enough time to reflect on my journey from a peacekeeper in the Middle East and walking the historic path of Jesus Christ and kneeling at the Western wall as I prayed to God to save Mrs. Abrams’ life, to where I chatted with Deepak 25 years later. A quarter of a century had passed in the blink of an eye. I do not know how much longer I will live.

I returned to the United States a month later, and lived my life without the need for pain killers or alcohol at the time I’m writing this. I have no plans to return to living any other way.

I believe everything’s a series of causes and effects; end a cause to end its effect. I also believe everything’s a choice. Mindfulness helped me see that. That’s how I know.

Whatever you believe, I wish you happiness, and the causes of happiness; freedom from suffering, and the causes of suffering.

Return to the Table of Contents.