A Part in History: The Big Picture

But then came the killing shot that was to nail me to the cross.

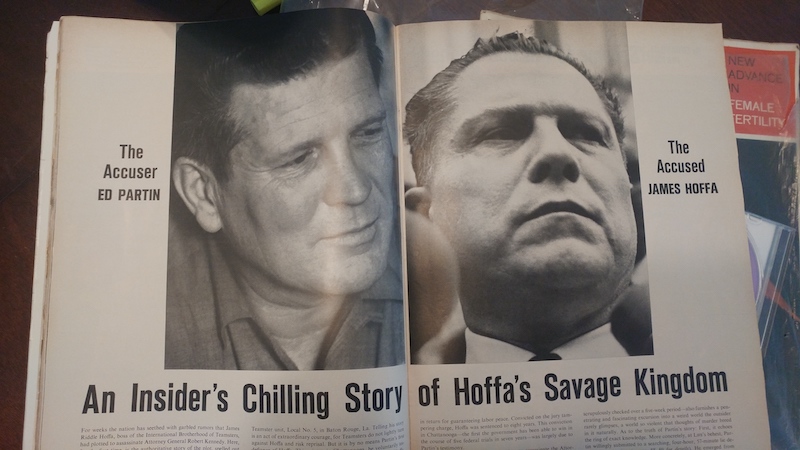

Edward Grady Partin.

And Life magazine once again was Robert Kenedy’s tool. He figured that, at long last, he was going to dust my ass and he wanted to set the public up to see what a great man he was in getting Hoffa.

Life quoted Walter Sheridan, head of the Get-Hoffa Squad, that Partin was virtually the all-American boy even though he had been in jail “because of a minor domestic problem.”

– Jimmy Hoffa in “Hoffa: The Real Story,” 19751

I’m Jason Partin.

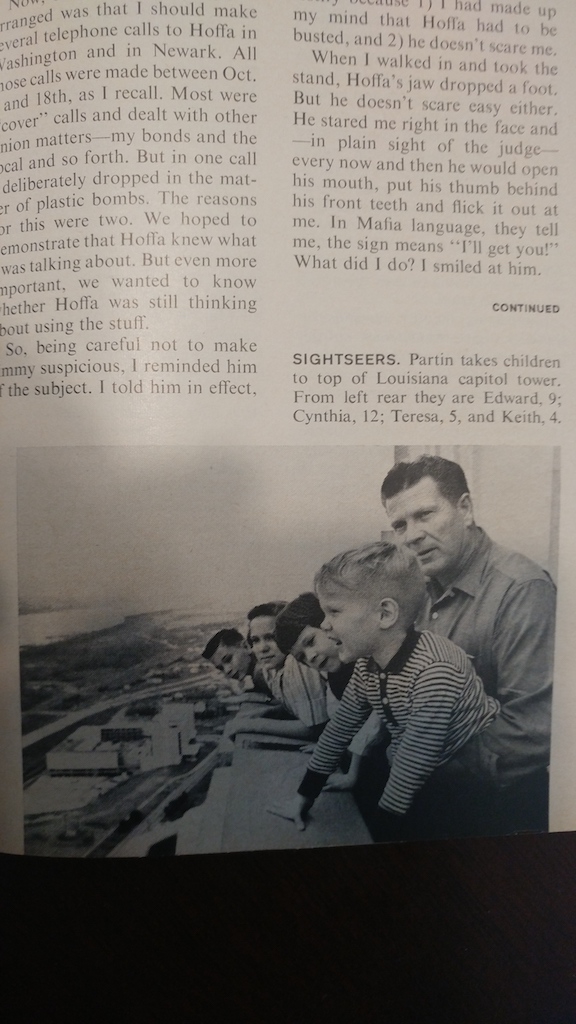

My father is Edward Grady Partin Junior, a former drug dealer who went to prison during President Reagan’s war on drugs in the 1980’s, and now a public defense attorney in Louisiana. My grandfather was Edward Grady Partin Senior, the Baton Rouge Teamster leader famous for sending International Brotherhood of Teamsters president Jimmy Hoffa to prison in 1964, ten months after President Kennedy was assassinated. He was also known as a “person of interest” in President Kennedy’s assassination.

Everyone in Baton Rouge called my grandfather Big Daddy. Hoffa, a teetotaling athlete but relatively small in stature, surrounded himself with big brutal men, and he was enamored by Big Daddy’s classic good looks: tall, broad-shoulders with a narrow waist, strawberry-blonde hair, sky-blue eyes, a consistent subtle smile, and charming southern drawl. In his second autobiography, penned from prison and published just before he vanished from a Detroit parking lot on 30 July 1975, in a chapter about Big Daddy, Hoffa began by saying: “Edward Grady Partin was a big, rugged guy who could charm a snake off a rock.”

In 1962, Hoffa asked Big Daddy to be what court records would eventually call a sergeant at arms. He stood between Hoffa and the doors of hotels and meeting rooms, listening to Teamster business while keeping guard against the country’s most notorious mafia hitmen and FBI agents out to get Hoffa. At the time, US Attorney General Bobby Kennedy and FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, under President Kennedy’s orders, had already spent years and untold millions of taxpayer dollars to fund 500 federal agents focused on nothing but pursuing Hoffa in what was dubbed by media as the “Get Hoffa Task Force.” Hoffa laughed off their efforts, and a public feud unfolded and was a main gossip topic among Americans for years. Their public spectacle was so fierce it was known as “The Blood Fued.”

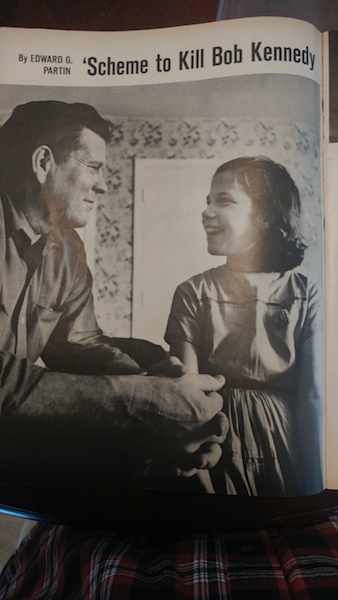

A few months before Big Daddy was Hoffa’s trusted sergeant at arms, Hoffa plotted to kill Bobby and his family by blowing up their home. He asked Big Daddy to help by obtaining military plastic explosives, C4, from Big Daddy’s colleague, New Orleans mafia boss Carlos Marcello, who controlled shipping in and out of America’s second largest port and traded extensively with Fidel Castro’s military in Cuba, despite President Kennedy’s 1961 embargo and the recent failed Bay of Pigs invasion. Baton Rouge’s much smaller Mississippi port was only an hour or two upriver, bypassing federal inspectors, and local stevedores loaded goods onto Big Daddy’s trucks driven by Teamsters fiercely loyal to him and ostensibly loyal to Hoffa, so it was a reasonable request for an horrific plot.

Big Daddy declined, saying he drew the line at killing kids (though he’d be arrested a few months later for kidnapping the two and six year old children of a fellow Teamster who had lost a court custody settlement, the “minor domestic problem” Hoffa referenced with ironic “bunny ears” almost daily for the final eleven years of his life). Soon after, behind closed doors and without being recorded, Hoffa asked Big Daddy to help him evade a small, state-level trial in Chatanooga, Tennessee, by bribing or otherwise intimidating a juror into voting not guilty. Hoffa didn’t suspect that Bobby and Hoover had already offered Big Daddy a deal if he’d report everything he heard from inside Hoffa’s camp, someone supreme court records would later call “a walking bugging device.”

FBI director J. Edgar Hoover validated Big Daddy’s claim via his top FBI agents and an series of lie detectors tests, then Bobby, who was his boss, and they and met with President Kennedy and warned him that Hoffa’s threat could be meant for him instead. Kennedy said there was always a threat, and he dismissed the warning. He wash shot and killed as he rode through his open convertible four days later, 22 November 1963.

Ten months after Kennedy was murdered, Big Daddy stood up from his seat behind Hoffa as the prosecutor’s surprise witness against his boss. Courtroom journalists wrote that the otherwise stoic and focused Hoffa’s face paled and he uttered: “My God, it’s Partin.”

Big Daddy smiled and calmly testified against what was then considered the world’s most powerful man not a Kennedy, and in a courtroom filled with bodyguards and hitmen. Big Daddy was so charming that the jury deliberated a mere four hours before finding Hoffa guilty. Bribing a juror is a federal offense, which brought Hoffa into Bobby’s territory. He was convicted of a felony and sentenced to prison, not for murder or racketeering, but for jury tampering because he implied – not asked – that Big Daddy bribe a juror. There were no witnesses or recordings, and the juror had never been approached. After the world’s most expensive and fruitless pursuit of one man by a government, Bobby won because of Big Daddy’s charm.

Hoffa had a sense of humor; he titled Chapter 10 of his autobiography The Chatanooga Choo Choo because he felt Bobby Kennedy railroaded the justice process to get him in the Chatanooga, Tennesse trial, and Chatanooga Choo Choo was a famous song back then that spoke to his readers. At the same time he was making jokes, Hoffa was using the $1.1 Billion pension fund and his army of attorneys to appeal the verdict and fight his the conviction all the way to the supreme court, challenging both Big Daddy’s character and Bobby and Hoover’s assault against the 4th Amendment. That Amendment was penned by a quill held by the hands of America’s founding fathers, a single sentence that unambiguously gave citizens the right to privacy, and restricted government search and seizure to a process that included a warrant specifying what is to be searched and where it would be found. Big Daddy had been tasked by Bobby and Hoover to find “something,” or “anything,” they could use against Hoffa.

Bobby, silent about believing his brother was killed by Hoffa, hovered over Hoffa’s trial like a hungry vulture, intense and brooding. To protect their witness, Hoover and Bobby plastered Big Daddy and my family across national media and dubbed Big Daddy an all-American hero. Federal agents were assigned to follow my family in a nationally publicized precedent because the Partin were not protected witnesses, they were blatantly in the face of everyone and Big Daddy’s fame at home rose. Big Daddy returned to Baton Rouge and continued running the Teamsters, taking my dad and uncle deer hunting as if nothing unordinary had happened.

In 1966, Hoffa’s supreme court case was overseen by Chief Justice Earl Warren, a 40 year veteran of the court already famous for landmark cases like Brown versus the Board of Education that addressed segregation, Roe versus Wade that addressed abortion, and the case that led to Miranda Rights being read to anyone arrested to remind them of their right to remain silent, a horrific case of rape in Arizona where the defendant confessed to his arresting officer without knowing he had the right to an attorney before speaking.

Warren had also just led newly appointed President Lyndon B. Johnson’s investigation into Kennedy’s assassination, the 1964 Warren Report, that erroneously concluded that Lee Harvey Oswald, a marine veteran and New Orleans native who trained in the Baton Rouge civil air force under the alias Harvey Lee, acted alone when he shot and killed Kennedy, and that Jack Ruby, an air force veteran, low-level mafia runner, and Hoffa ally in Dallas, acted alone when he shot and killed Oswald in front of the Dallas police station and on international live television two days later.

(U.S. law does not try deceased people, so Oswald was never convicted. The trial that called Big Daddy a “person of interest” in Kennedy’s murder was not against Oswald, it was against a New Orleans businessman who worked with local FBI and CIA agents stationed next door to an office Oswald used to organize pro-Castro rallies. That trial was spearheaded by New Orleans district attorney Jim Garrison, and it was followed daily for years in the late 1960’s, fueling the overwhelming international sentiment that Kennedy was killed as part of a larger conspiracy reaching into all aspects of government.)

Because of Warren and Hoffa’s fame and growing conviction that Kennedy’s murder was part of a conspiracy involving the New Orleans FBI and CIA offices, Hoffa versus The United States was followed daily by practically every American.

He was the only justice to come from a criminal prosecution background, yet he opposed Bobby and Hoover’s methods. Of nine justices, only Warren voted against using Big Daddy’s testimony to sentence Hoffa to eight years in prison; six voted yes, two abstained. The name “Partin” was used on 24 pages of their verdict, and Chief Justice Warren attached railed against Big Daddy’s character and the injustice of using his testimony to convict Hoffa, mentioning “Edward Partin” 148 times in his three pages missive.

Warren’s comments and the 1966 Hoffa versus The United States decision, like all supreme court cases used to steer America’s system of justice, has been a public document since, and is still, to this day taught in most American law schools, including the Kennedy’s Harvard, as an example of how clear-cut Amendments in America’s Bill of Rights can change after a supreme court decision.

The 4th Amendment simply says that Americans should be protected from illegal search and seizure, and that anything obtained by subterfuge needs to be authorized by a warrant specifying exactly what is to be seized and where it is. Warren was the only one of nine justices to vote against using Big Daddy’s testimony to convict Hoffa. He wrote:

“I see nothing wrong with the Government’s thus verifying the truthfulness of the informer and protecting his credibility in this fashion. (Lopez v. United States, 373 U. S. 427 (1963). This decision in no sense supports a conclusion that unbridled use of electronic recording equipment is to be permitted in searching out crime. And it does not lend judicial sanction to wiretapping, electronic “bugging” or any of the other questionable spying practices that are used to invade privacy and that appear to be increasingly preva-lent in our country today.”

and a few paragraphs later:

“Pursuant to the general instructions he re- ceived from federal authorities to report “any attempts at witness intimidation or tampering with the jury,” “anything illegal,” or even “anything of interest,” Partin became the equivalent of a bugging device which moved with Hoffa wherever he went.“

Without Big Daddy, Warren said, “there would probably have been no convictions here,” and to use his testimony would “pollute the waters of justice.”

Warren may have been right; 25 years later, immediately after Osama Bin Laden orchestrated the 9/11 Twin Towers and Pentagon attacks, President George W. Bush and US Attorney General John Ashcroft used Hoffa versus The United States as a foundation case for the PATRIOT Act, which allowed cell phone monitoring and other search and seizures of all Americans without a warrant, among many other things still debated in law schools as whether or not our constitution has been bent so much that it’s breaking.

After his loss in the supreme court, Hoffa began serving his sentence year sentence in a New Jersey federal penitentiary; another charge was added, bringing his total sentence to eleven years. Conspiracy theorists read Hoffa versus The United States and concluded that the supreme court, judges appointed by presidents for life terms and supposedly immune to outside influence, was bribed or blackmailed to convict Hoffa. Hoover, already known as a manipulator of public figures during the McCarthy era of communist witch-hunting, because he had a massive library of surveillance of politicians in illicit, immoral, or private acts like adultery homosexuality, had somehow tapped every one of the justices except Warren.

Jack Ruby, a former Hoffa ally who had called Hoffa multiple times before and after Kennedy was killed, was in prison then after having been convicted of first degree murder two years prior; when he shot Oswald, it was the first murder ever witnessed on live television, so there were millions of witnesses, and he immediately confessed, so there was no doubt of his guilt; the first-degree charge came from Ruby slipping that he had planned to shoot Oswald more than once, which meant it was not a lesser charge for third degree murder resulting from momentary passion. A year after Hoffa began his sentence and after Ruby changed his statements multiple time, Ruby died of complications secondary to lung cancer, crying that the FBI had been poisoning him with cancer pills; he had been a lifelong smoker before the risks were so well known.

Two months before Ruby died, New Orleans district attorney Jim Garrison arrested New Orleans businessman Charles Shaw for Kennedy’s murder. Garrison’s Grand Jury allowed New Orelans police officers to round up all of the FBI and CIA agents who had worked with Shaw and Oswald. That was the trial where Big Daddy was “a person of interest,” but the photo evidence of him with Oswald and Ruby vanished, so the Grand Jury did not indict him. Shaw was found not guilty, and to this day the court records and Garrisons’s book are cited by conspiracy theorists.

(In the 1992 Oliver Stone film based on the book, JFK, the towering 6’6″ Garrison has a cameo portraying Chief Justice Earl Warren, showing the long-lasting impact he had on conspiracy theories.)

Hoffa wasn’t following the Shaw trial because he was isolated in a harsh prison cell. After a lifetime leading labor unions, he spent his middle age days assigned to a prison work detail and pounding prison-made mattresses, and spent his nights in a small cell, pondering how Big Daddy fooled him and how to get in control of his Teamsters, which were being run by someone he thought would be a puppet, but who had embraced the power and his relationships with politicians and mafia families using him to tap into the Teamster pension fund; Hoffa was so focused on returning to power that he wrote that his only regrets were engaging in battle with Bobby and trusting Fitzsimmons. Unsurprisingly, Hoffa also shifted his focus away from labor reform, something he saw as necessary when humans were crushed by management during the Great Depression, to prison reform. He said the system was worse than he imagined, something my father would also attest to, just like Big Daddy and my great-Grandpappy Grady, who also served jail time around the turn of the century.

Most of America was overhelmed with all of the news and theories about Hoffa and Shaw and Kennedy’s assassination, especially because the dominating news became the escalating conflict in Vietnam. Former vice-president and newly appointed president Lyndon B. Johnson had reversed President Kennedy’s intent on keeping the number of American forces in Vietnam to under 55,000, saving American lives by nurturing and using Special Forces, colloquially called Green Berets, to train local forces instead; under Johnson, the draft system exploded, and around 550,000 young men and women were deployed. At the same time, racial violence sparked more focus away from Kennedy’s murder, even though Martin Luther King Junior was shot and killed in 1968 by a sniper who was then shot and killed, similar to what unfolded with Kennedy, and even though Bobby was shot and killed soon after by the redundantly named Serhan Serhan, who has served in prison since.

I’m not an expert in history or sociology, but I believe America had simply become fatigued with all of the killing, which may explain the 1968 west coast “summer of love,” where mostly caucasian young adults took prodigious amounts of psychedelics to escape the news, a pattern that I believe persists with prescription anti-drepressants and anti-anxiety pills today. Hoover’s blackmail methods would be irrelevant in today’s world, which may be why few young people understand why a senator, congressman, president, or supreme court justice would violate American ideals because they consumed narcotics or engaged in hanky-panky behind closed doors, especially with the reputation of the 1960’s reputation as a time of free love and abundant drugs.

President Nixon pardoned Hoffa in 1971 (just before I was conceived by a 17 year old Edward Partin Junior, a handsome high school drug dealer usually high on a prodigious list of narcotics and who seemingly deflowered half of the teenage girls in Baton Rouge), with the unusual requirement that Hoffa travel to Vietnam and use his labor organizing skills to negotiate the release of American prisoners of war. Hoffa agreed, but instead focused on regaining control of his Teamsters from Fitzsimmons. (My dad, who dropped out of high school and didn’t have the waiver against being drafted by being in college, somehow avoided service in Vietnam.)

Hoffa vanished from a Detroit parking lot on 30 July 1975. His body has never been found, despite dozens of television specials focused on things like digging up New Jersey football fields and using the latest genetic testing in homes, crematoriums, and anywhere so-called experts said he was disposed.

I began kindergarten a year after, and I never met any of the men I’ve discussed, except for, of course, Big Daddy, who had taught me to hunt with a rifle and skin deer with a knife in the forests around one of his Baton Rouge houses; at home, he was an ideal grandfather and had a knack for teaching marksmen, and twelve years later I’d be awarded expert marksman badges with every weapon the U.S. army and NATO had to offer; I would owe it not to army training (which wasn’t that effective – even Lee Harvey Oswalds marine marksman records show he was an abysmal shot), but from my few years knowing Big Daddy before he finally went to prison in 1980, when I was a sponge and listening to everything he and my dad said.

_______________________________

In 1983, when I was in middle school and helping my dad tend his marijuana fields in the forests where I used to hunt, Big Daddy was portrayed by the famous actor Brian Dennehy in the anticipated two-part film about Hoffa and his battle against the Kennedys, “Blood Feud.” America knew how Big Daddy and Hoffa looked and sounded, so producers found actors that matched what people expected. Brian was less famous than my grandfather back then, but he was an up-and-coming star known for his “rugged good looks,” green-blue eyes, and charming smile. Robert Blake was chosen as Hoffa; he was already famous, a child actor, army veteran, and adult star known for a career that was “one of the longest in Hollywood history.” Conveniently, Blake looked like the intense, square-jawed Jimmy Hoffa.

A daytime soap opera heartthrob portrayed Bobby Kennedy in a relatively smaller role, because the film focused on Hoffa and Big Daddy. One slowed down and showed a close-up of Blake, alone with Big Daddy and lost in thought, mimicking tossing a bomb into Bobby Kennedy’s home. That’s when he asked Big Daddy to get C4. Dennehy refused in his tough-but-charming character. Blake’s other scenes were more reminescent of Hoffa’s media appearances, and he won an academy award for “channeling Hoffa’s rage.”

(Coincidentally, Dennehy’s breakout role came later that year in another film with blood in the name, “Rambo: First Blood.” He starred alongside Sylvester Stalone and portrayed a rugged but fair Korean War veteran and small mountain-town sherif who led the hunt for Rambo, a Vietnam special forces veteran, like the ones sent by Kennedy and trained in the now-named Kennedy Special Warfare Center, wandering America with PTSD, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Dennehy’s fame rose quickly. To increase his tough-guy image among fans, Dennehy falsely claimed he was a real-life Korean war combat veteran; after admitting his lie, something veterans call “stealing valor,” but he recovered and went on to become one of the most celebrated actors of his generation. He died in 2020 during the Covid-19 pandemic, a month before his final film debuted online, in which he ironically portrayed an aging Korean War veteran in modern times. Robert Blake would be charged with murdering his second wife, file bankruptcy, and die in 2023 at age 89; his list of films, television, and plays on Wikipedia takes several pages to scroll through. I never followed the daytime soap opera’s career.)

Big Daddy was released from prison early due to declining health, and he returned home in 1986, my sophomore year in high school and first year on a wrestling team; he was a deflated version of himself, but still had that same smile, one that looked as if he knew the funniest joke in the world that he’d never share. Big Daddy, said from prison that he Dennehy did a fine job portraying him. He died in 1990, my senior year of high school and two years after Rambo, Part III was released; I never asked what he thought Denney’s later career or the Rambo franchise. He was a dishonorably discharged marine, and I never heard him comment on anything having to do with veterans.

In 2019, Big Daddy was portrayed by the burly actor Craig Vincent in Martin Scorcese’s opus about the Jimmy Hoffa and the American mafia, “The Irishman.” Scorsese raised $270 Million and hired a long list of Hollywood’s most famous actors know for gangster films, like Al Pacino, Robert DeNiro, Joe Pesci, and about a dozen others. Craig, a 6’5″ barrel-chested brute on film but kind and cheerful person in life, as chosen to portray Big Daddy because he had worked with Scorsese before, portraying a big, brutal thug alongside Pacino and Pesci in Scorsese’s Las Vegas mobster film, “Casino.”

Scorsese based The Irishman film on a memoir called “I Heard You Paint Houses,” co-written by one of Big Daddy’s peers, Frank “The Irishman” Sheeran, a former WWII combat infantryman with two years of experience killing Germans, a Teamster leader appointed by Hoffa himself, and mafia hitman who spent 13 years in prison for racketeering before writing a memoir that says he killed Hoffa. To “paint a house” was mafia code for killing someone by painting a wall red with their splattered blood, and Frank painted houses as a side-gig while he ran a local Teamsters union.

Frank knew Big Daddy well and spoke of him reverently in his memoir, saying that because Big Daddy knew Marcello, Hoffa assumed he also painted houses. But those parts were omitted from The Irishman film, because Scorsese said he was making an entertaining film to sell tickets, not a documentary. He focused on Frank’s claim of killing Hoffa and reinvented Big Daddy as “Big Eddie,” a northeast Italian brute who matched Craig’s Italian-American complexion and accent. Big Daddy’s role shrunk to fit the big screen.

The Irishman was released in theaters the summer of 2019 with lines of people waiting to see it. When the Covid-19 pandemic shuttered theaters globally in 2020, Netflix bought rights to The Irishman and it set global streaming records at the same time that Brian Dennehy’s final film was being streamed by people who probably didn’t know the connection. For the next two years, hundreds of millions of people all over the world saw a fictionalized glimpse at my family’s part in history.

I had chatted with Craig a few times when he researching his role as my grandfather. Craig had called my uncle, Kieth Partin, first, because Keith was president of the Baton Rouge Teamtsers like his father had been. Keith was too involved to see Big Daddy from an outsider’s perpspective. Craig tried to peak with my great-uncle, Doug Partin, Big Daddy’s little brother and Keith’s uncle, who had been the Baton Rouge president for thirty years after Big Daddy went to prison in 1980, but Doug, an air force veteran, was aging in a Mississippi veteran’s convalescent home with diminished mental alertness, probably early stage dementia, and he wouldn’t stop talking about his recent self-published and unedited autobiography, “From My Brother’s Shadow: Teamster Douglas Westley Partin Finally Tells His Side of The Story.” Craig then called my aunt, Janice, Big Daddy’s oldest daughter who had married and had a different last name, but still ran the Partin geneolgy website; she broke down into tears and was unable to help.

I couldn’t help, either. Craig and I chatted on the phone for a few hours every time we spoke. Craig’s mother had coincidentally worked with the New Jersey mafia, and he grew up knowing the names of characters with whom he shared on the screen. He knew I came from three generations of Teamster leaders, and that the current International Brotherhood of Teamsters president was James R. Hoffa Junior, who had become an attorney, like my father, but had been elected to take the reigns of his father’s union. We spent more time discussing the bigger picture of nurture versus nature than Big Daddy’s character.

Though I didn’t have my thought organized enough to say so concisely, I felt the answer to Craig’s questions was, of all places, buried in my finals match and Big Daddy’s funeral, which was covered by national news and packed with local politicians and celebrities. I grew up in a small capital city of around 150,000 people who followed the Partins in the news daily, and since childhood I always focused more on their reactions than analyzing my family’s. I felt that a person’s personality doesn’t convey how people feel around them, and to accurately portray Big Daddy would require focusing on others, not him. My feeling wouldn’t be feasible in a film focused on someone like Frank Sheeran, a liar, thief, murderer, racketeer, and barely functioning alcoholic whose words were polished by a professional co-writer. Sheeran died in 2003, just before his book was published, but his agent received generous compensation for the film rights that Scorsese obtained in 2014, and, justifiably so, focused on maximizing his company’s profits by focusing on Frank’s claims.

Scorcese had so much momentum from his $257 Million investors that the film proceeded focused on Frank. Craig’s 20 minute role was edited down to five minutes so that Scorcese could squeeze him into a film that was already a whopping 3 hours and 24 minutes long, more than the patience of even the most dedicated film aficionados.

But, to convey the bigger picture, Scorsese, probably the most celebrated and revered film makers of both my generation and my father’s generation, still listed as creating the greatest films of all time, like Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, Goodfellas, and a list on Wikipedia about as long as than Earl Warren’s list of reasons to distrust my grandfather, lowered a wide-angle camera to peer up at all the famous actors with Craig stoically standing behind them, looming over Hoffa and Frank and other leaders of the time, his size exaggerated by the camera angle, a puppet master of publicly known men. The scene was reminiscent of Raging Bull, which used camera angles to bring the audience into the boxing ring with Robert DeNiro and show the brutality of battling a larger foe; Big Daddy, a heavyweight boxer in his late teens and early 20’s, would probably appreciate the comparison.

That scene was effective at telling a complex story, though it’s unlikely that Big Daddy wasn’t smiling in real life. And, despite The Irishman’s claim, the FBI case looking for Hoffa’s body is still open. Every few years a new agent younger than shirts I wear is assigned to the case, and he – invariably it’s a male agent – uses the same internet search as Craig Vincent, with no more background than having read Wikipedia and watched Blood Feud; and, after 2019, also The Irishman.

But Craig had a vested interest in details about Big Daddy that no FBI agent or investigative journalist shared. He knew the facts, which are available to anyone with the internet and who is willing to order a few books rather than read blogs like the one I’m writing now, and he had watched old black and white news reals of Big Daddy. He studied Brian Denney’s portrayal, and he read countless books published after the JFK Assassination Report was partially released in 1992, written by Hoffa’s attorneys, Teamster leaders, and mafia henchmen.

All of them expounded on Big Daddy’s conflicting charm and brutality; but, Craig still couldn’t understand how Big Daddy could fool so many people, especially Hoffa and the mafia with their street-smarts, and Hoover’s FBI known for the world’s most sophisticated surveillance methods back then. His question was more insightful than any investigator I ever met, and our chats sowed a seed that sprouted in my mind during the two year global shutdown that followed Covid-19.

I dusted off old family letters and photos, and spent two years of the Covid lockdown pondering how to answer Craig’s question of “how,” a fair question from an actor, but focusing on “why,” which is how my mind has always worked and probably why I didn’t follow my family’s footsteps.

I had followed presidents since the JFK and MLK Assassination Report since 1993, almost immediately after Oliver Stone’s JFK film sparked voters to demand incumbent president Bill Clinton release it. At the time, I was a paratrooper on President Bill Clinton’s quick-reaction force, and I held secret clearance and a diplomatic passport. (I was like a lot of teenagers who rebel against their family values, typically getting into drugs or crime; in my case, I joined the army and became an engineer who enjoyed a good film and researched history in my spare time.) But, even with my clearance I didn’t learn more than what was released in 1992.

A deluge of books and films followed the public’s access to the JFK Assassination report, probably because people felt exonerated to talk and because some hoped for a lucrative book and movie deal. The hubbub drowned my interest. I became intrigued again twenty-five years later, after speaking with Craig. Armed with a library card and the internet, I began looking at history with fresh eyes that now saw through reading glasses typical of middle aged men.

I Googled what I could using my Macbook and wireless WiFi access, concepts unfathomable to even J. Edgar Hoover, who died in 1972, the year I was born, after 48 years of running the FBI under eight presidents and with access to America’s top technology and practically unlimited budgets. Not much had changed about America’s understanding of Kennedy and Martin Luther King’s murder, and with all the war and violence in the news America still seems, on average, distracted away from focusing on productive improvement on our system.

On a whim, I distracted myself by Googling my name for the first time.

There are many people named Jason Partin on the internet. Most are average people in their communities, and post photos and opinions on Facebook or Twitter (now “X” thanks to the engineer Elon Musk) typical on noisy social media rants reminiscent Doug’s self-written and unedited autobiography. A few are criminals, and one is a mixed martial artist who coincidentally looks like a younger version of me and has a few Youtube videos of him in cage matches.

One is my cousin, my great-uncle Joe Partin’s son and Big Daddy’s nephew, who is two years younger than I am and was the Zachary High School Bronco’s football star when I was wresting for the Belaire High Bengals in the 1980’s; he went on to play football for Mississippi State, and today his smiling face looks down from Lamar Advertising billboards along I-110 between downtown Baton Rouge and Zachary, promoting his physical therapy business. His dad was Coach Joe, Zachary’s principal and football coach and a beloved community leader; like I did, they both rebelled against typical Partin values.

I’m mostly offline, known by friends and colleagues for practicing my Miranda Rights, a trait I picked from my family’s association with the FBI, mafia, assassins, and drug dealers. I never discussed my family history. By the time I was an adult in San Diego, America’s short-term memory had forgotten the fame of the Partin name, so no one asked.

When Craig and I spoke, I was the Jason Partin on the website of The University of San Diego Shiley-Marcos School of Engineering. I had gone to college and then graduate school after the military, and by the late 2000’s I was leading a few college engineering courses and running an innovation center called Donald’s Garage, named after Donald Shiley. He was an engineer who co-invented the world’s most financially successful heart valve in his garage, a tiny black gizmo made from the inert material pyrolytic carbon whose patents were so strong that Pfizer purchased the product in the 1980’s for something like $780 Million, a huge sum of money back then, enough to make three or four “The Irishman” films today for what distills down to a few words written in a patent, a concept installed into our county’s founding documents by the same men who penned the 4th Amendment, a way they saw to motivate innovators and grow America’s prosperity using new and unforeseen technologies. All of my courses centered around entrepreneurship, so the patent process and America’s legal system were fresh in my mind.

In the university’s photo, I have the same smile as my cousin’s billboards, the exact smile Big Daddy had inherited from his mother, my great-grandma Foster, the common genetic link between that Jason and me; it’s mostly a facial feature from our high cheekbones pulling up on the corners of our mouth, making it seem like we’re smiling even when we’re not. (Our eyes crinkle when we really smile, just like Big Daddy’s and Grandma Foster’s.) That same photo was used for the University of San Diego’s technology incubator, called The Basement, where I was an advisor for their entrepreneurship program.

I’m also the Jason Partin listed on the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s website for a handful of medical device inventions under the names Jason Partin and Jason Ian Partin. Coincidentally, my third invention used pyrolytic carbon to resurface the wrist joint and I cited Donald Shiely’s patent fifteen years before his widow donated $21 Million to USD in 2017, creating Donald’s Garage with hopes it will nurture future innovators. No photos are attached to patents, and a few other Jason Partins had patents, though I was the only one focused on medical devices.

Most of my inventions are also focused on healing small joints and bones, like in the spine and hands and feet, like a two-piece bone screw connected by a tiny spring to pull compression across a fracture site. The patents are less focused on how to heal than on why existing treatments fail, and what we can do to improve. The finger implant with a tiny spring traces back to a specific springtime in Baton Rouge, the day of Big Daddy’s funeral on 11 March 1990. It was covered by national news and available on the NY Times and LA Times web sites, and I’m unnamed but listed as one of Big Daddy’s grandchildren; only a few people noticed that I showed up with my two left middle fingers buddy-taped; the ring finger had been broken two weeks earlier in the Baton Rouge city wresting tournament finals, and was just beginning to heal. It healed askew because calcium built up on one side, and to this day my two fingers part like Dr. Spock’s split-finger salute in Star Trek; staring at that split finger salute every time I did pushups beginning in basic training that summer probably steered my thoughts to healing it; had doctors had my inventions then, I wouldn’t be making the same Star Trek jokes at San Diego’s Comic Con that I do today.

I’m also the Jason Partin listed on the Louisiana High School Athletic Association’s website as having been pinned one minute and twenty seconds into the second round on 03 March 1990, winning that year’s silver medal at 145 pounds. I’m also listed in three congressional committee hearings for what happened in the final days of the war during the battle for Khamisiyah airport on 04 March 1991, almost a year after my finger healed.

To me, my 1989-1990 wrestling season, Big Daddy’s funeral, and the subsequent first Gulf war of 1990-1991 answers why Big Daddy, Hoover, and Bobby did what they did, though I still don’t have a concise answer that would go viral on Twitter or X or whatever the future holds. (As students in my class and wrestler’s on my teams have joked for 40 years, I’ve never given a concise answer for anything, and I use too many parenthetic thoughts for a generation growing up with terse and easily spread social media summaries.)

At the beginning of Covid, an aspiring San Diego filmmaker set up a movie camera in Balboa Park and asked people passing by if they’d lower their mask and tell their biggest secret. Not knowing what would happen, I said sure, why not, and told her that my grandfather, Edward Grady Partin, was behind President Kennedy’s assassination.

A week later the video went viral on both a new platform called Tik Tok. The 20 second clip went viral, and was shown to my by a friend’s teenage daughter, who almost didn’t recognize me without my grey beard and said loosing it shaved ten years off my age. The filmer also posted a slightly longer version on the established Youtube as the lead secret of a handful of people from that day. Within three days, it was seen by 10.2 Million people and had 6,837 comments. According to the consensus, I have “a charming smile,” and “seem trustworthy,” echoing perceptions of Big Daddy sixty years before. I inherited his smile, which is more of a facial feature from our high cheekbones pulling up on the corners of our mouth and a perpetual cheerfullness; when he smiled or I smile cheerfully, our eyes crinkle.

A few hundred comments said I should “watch out,” because “someone” will come after me; at least fifty said it would be the FBI or CIA who would silence me.

Within a week Wikipedia wobbled back to parrot The Irishman film’s description of Big Daddy. It hasn’t changed since, and I never learned if “someone” went after any of the Jason Partins for what I said. If they did, I think it would be interesting to learn what happened if they encountered the 220 pound cage fighter who shares my name.

After the Wikipedia episode, I spent the Covid-19 pandemic working on a memoir showing what I recall, hoping someone else can see the big picture using what I wrote. It is on my website, JasonPartin.com, waiting for the next time a film about my family is released during a global pandemic. Maybe, like Frank “The Irishman” Sheeran, what I write will spark a film – or stream or virtual experience or whatever the future of media becomes – to help correct the course of misinformation that began with Big Daddy’s smiling face in Life Magazine, where he was erroneously dubbed an all-American hero, and to finally use all of our information to improve society for everyone. It had been 60 years since Kennedy was killed, but the reasons why persist, and many of the people involved are still alive.

Like Frank “The Irishman” Sheeran, my grandfather was no hero. He was a rapist, thief, racketeer, adulterer, murder, rapist, kidnapper, and perjurer; and, according to my grandmother, he alarmed her when he stopped going to church on Sundays to lead Teamster meetings. But, he was, by every definition, a dedicated local Teamster leader, if not the loyal one Hoffa assumed.

As for nurture versus nature, the jury’s still out, and it’s taking much longer to reach a decision than it did to convict Jimmy Hoffa based on Big Daddy’s charming smile.

Go to the Table of Contents

- From “Hoffa: The Real Story,” his second autobiography, published a few months before he vanished in 1975 ↩︎