A Part in History, Part I

But then came the killing shot that was to nail me to the cross.

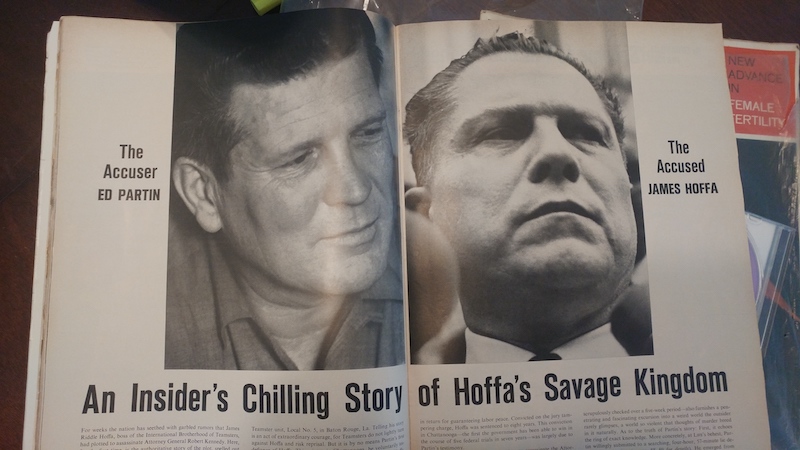

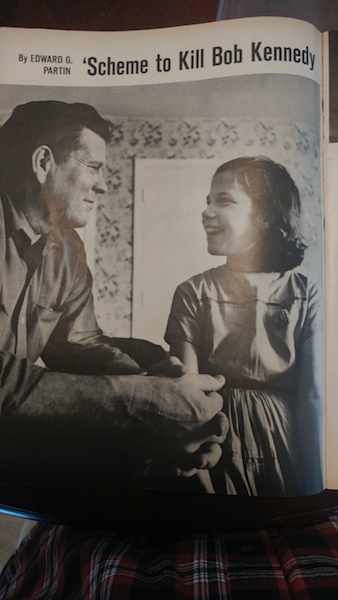

Edward Grady Partin.

And Life magazine once again was Robert Kenedy’s tool. He figured that, at long last, he was going to dust my ass and he wanted to set the public up to see what a great man he was in getting Hoffa.

Life quoted Walter Sheridan, head of the Get-Hoffa Squad, that Partin was virtually the all-American boy even though he had been in jail “because of a minor domestic problem.”

– Jimmy Hoffa in “Hoffa: The Real Story,” 19751

I’m Jason Partin.

Hillary Clinton broke my left ring finger on 03 March 1990; it healed askew, and to this day my two middle fingers have a gap above the middle finger that looks like Dr. Spock’s split-finger salute on Star Trek.

My father is Edward Grady Partin Junior, the rough-edged ex-con who became a public defense attorney, and is listed in the Baton Rouge phone book as Edward G. Partin, Attorney at Law. Despite being a former drug dealer, during the first Gulf war of 1990-1991 he was flow to Washington DC by congress so that he could argue the constitutional right to burn an American flag; soon after, he successfully sued the states of Arkansas and Louisiana and changed their laws preventing an ex-con from practicing law, owning a firearm, or voting.

Every law student in America learns that my grandfather was Edward Grady Partin Senior, the big, brutal Baton Rouge Teamster leader famous as the surprise witness who testified against International Brotherhood of Teamsters president Jimmy Hoffa, who was convicted of jury tampering based solely on my grandfather’s word. Hoffa lost his appeal to the supreme court, and the 1966 Hoffa versus the United States ruling is still taught in every American law school; his testimony against Hoffa changed the Constitution’s 4th Amendment against unlawful search and seizure without a warrant that specified what was to be searched for, why it was being sought, and where it was probably located. Sixty years later and after the 9/11 terrorist attacks on America, Hoffa versus The United States formed the foundation for President George Bush Junior’s 2001 PATRIOT Act, which allowed federal agencies to monitor hundreds of millions of Americans’s cell phones without warrants and without specifying why.

Though not as publicly known, my grandfather was also involved in killing President Kennedy, who had been assassinated on 22 November 1963, ten months before he testified against Hoffa, which is part of what this story is about.

The Hillary Clinton who broke my finger was not Hillary Rodham Clinton, who became a household name when Arkansas governor William “Bill” Clinton became president in 1992; the Hillary that broke my finger was the returning three-time undefeated Louisiana state champion wrestler, captain of the revered Baton Rouge inner city Capital High School Lions, and winner of the 1990 Baton Rouge city tournament after he broke my finger in the first round and pinned me one minute and forty seconds into the second round on 03 March 1990, one week before my grandfather passed away.

I attended my grandfather’s funeral with my two middle fingers still buddy-taped. Though not mentioned by name, the New York Times and Los Angeles Times included me as one of Edward Grady Partin’s grandchildren who attended his funeral. My broken finger wasn’t mentioned in news, but – as I’ll share later in this story – Walter Sheridan. He was the FBI agent who led Bobby Kennedy’s Get Hoffa squad of 500 agents for almost a decade and was, at the time of my grandfather’s funeral, an investigative journalist for NBC; he was a keen observer of seemingly minor details that told a larger story.

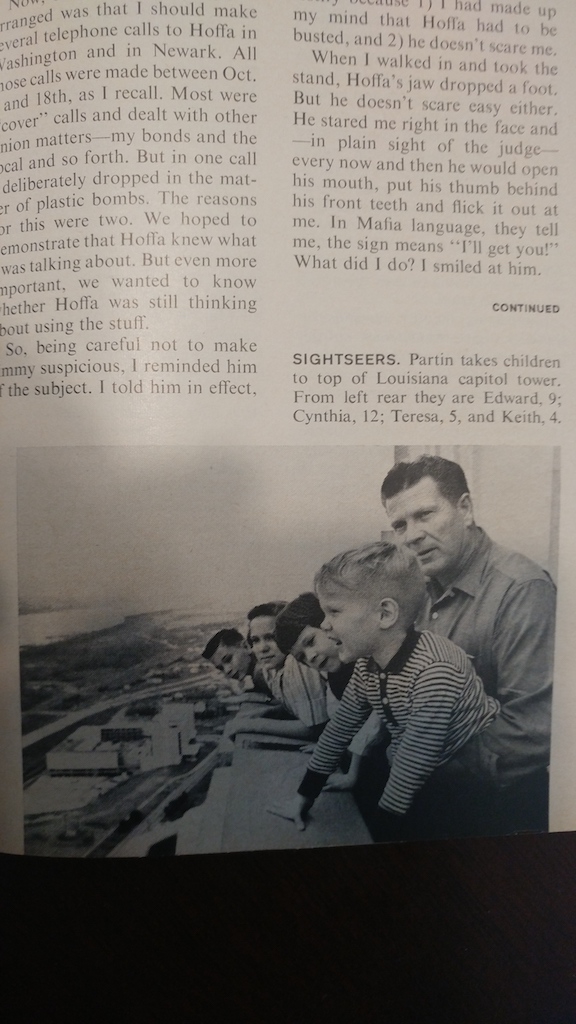

Everyone called my grandfather Big Daddy. He was what was then called classically handsome: tall, broad shoulders, narrow waist, strawberry-blonde hair, sky-blue eyes, a charming smile, and an soothing southern accent. In his second autobiography, published a few months before he vanished from a Detroit parking lot in 1975, Jimmy Hoffa described Big Daddy more concisely: “Edward Grady Partin was a big, rugged guy who could charm a snake off a rock.”

In 1983, Big Daddy was portrayed by Brian Dennehy in 1983’s “Blood Feud.” Big Daddy was more famous than Dennehy back then, but the young actor was chosen for what became his trademark:rugged good looks and a charming smile. Conveniently, he looked like a smaller version of Big Daddy. The iconic actor Robert Blake, whose intense and square-jawed face looked like Hoffa’s, won an academy award for “channeling Hoffa’s rage.” Some daytime soap opera heartthrob whose name I can’t recall portrayed Bobby Kennedy, and Ernest Borgnine portrayed J. Edgar Hoover.

In once scene, Blake, as Hoffa, is standing in a room with Dennehy, as Big Daddy, and Blake stares into space and slowly mimics tossing a bomb into Bobby Kennedy’s home. He describes using plastic explosives to kill Bobby and his family, and asks Big Daddy to get some from his contacts in the New Orleans mafia.

Big Daddy refused, saying he wouldn’t kill kids; but, in real life and soon after that 1962 meeting, Big Daddy was arrested for kidnapping two small children on behalf of fellow Baton Rouge Teamster Sydney Simpson, who had lost them in custody court. That kidnapping charge was the “minor domestic problem” that Hoffa sarcastically used “bunny ears” to describe how Bobby Kennedy and the FBI whitewashed my family’s history to protect their only witness against Hoffa. The film, like in real life, whitewashed his kidnapping charges, rape charges, and manslaughter charges, so that he was still seen as an all-American hero.

Forty years after Blood Feud, Big Daddy was portrayed by the burly actor Craig Vincent in Martin Scorsese’s $257 Million to make his opus about Hoffa in 2019, “The Irishman.” Craig was a 6’6″ Italian-American with a barrel chest, dark complexion. and northeastern tough-guy accent; he didn’t look like Big Daddy, who had strawberry blonde hair at the time, sky blue eyes, a whimsical subtle smile, broad shoulders, and a tapered waist. To adapt to Craig’s accent and darker complexion, Scorcese changed Big Daddy to be “Big Eddie.”

Scorsese focused the film on a colleague of Big Daddy’s, Frank “The Irishman” Sheeran. It sold out theaters until Covid-19 shuttered public spaces worldwide, then Netflix bought the rights and The Irishman set global streaming records; approximately one Billion people saw a simplified version of my grandfather’s part in history.

Craig and I spoke when he was researching his role, and though the role was changed to fit him, he wanted to know what were the personality traits that led Big Daddy to fooling so many people. I couldn’t answer concisely, and I still can’t. My memory of him is so intertwined with wrestling Hillary Clinton that, during Covid, when almost out of every 10 people on Earth were watching Craig portray a simplified version of my grandfather, I spent it trying to write a memoir about my experiences with Big Daddy, but it turned out to be more about wrestling Hillary Clinton.

I saw Hillary for the first time on a Wednesday afternoon in mid-November of 1989, when the Baton Rouge air was becoming less muggy and the days were short. Immediately after school let out at around 2:30 in the afternoon, 15 wrestlers from the Belaire High School Bengals piled into the sliding side door of Belaire’s big blue Chevy van.

I had just turned 17 years old, a senior at Belaire, and co-captain of the Bengals. I stood outside the van and counted as wrestlers crammed in. It was our first dual meet of the 1989-1990 wrestling season, and our energy was palpable because it was our first match since the end of my junior year; herding 15 teenagers was like encouraging crawfish to band together into a team.

Seven other Bengals piled in a family Astro minivan besides us. It had been borrowed by two of the wrestlers, Big-Head Ben Abrams, an 18 year old, third-year 189 pounder, a Bengal baseball star and enthusiastic but only average wrestler who, to this day, insists his nickname was just Big Ben, like the clock in London; and Ben’s little brother, Todd “Mace” Abrams, a 16 year old, first-year 164 pounder who was the state martial arts champion specializing in Ku Kempo, but who was only a mediocre wrestler who suffered from asthma. They were joined by Steve Long, a great-nephew of Louisiana governors Huey Long and Earl K. Long, Belaire’s 171 pounder, and the Abrams’s neighbor; he was what people called a “corn fed country boy,” strong enough to win most matches by brute force.

I stood by the door of Belaire’s Chevy with my hand on the handle, and waited for our 275 heavyweight, a big bellied rapper named Dana “Big D” Miles, to squeeze in to the bucket seat beside Michael, our 135 pounder and Belaire’s Junior ROTC captain. They and Miasha, a second year wrester and our 151 pounder, lived within walking distance of Belaire and had made every practice for three weeks. They were the only African Americans on our team.

I’m one of the whitest people you could imagine. I’m easily sunburned, and today I have grey hair and a big bald spot, but back then I had freckles from a long summer of sunshine, and thick auburn-red hair I kept as a mullet that ended at collar-level, which was a USA Wrestling requirement. I weighed 141 pounds, but was our 145 pounder and was an above-average wrestler. I sat next to Big D, who pushed Michael against his window. Michael and I were each the size of one of Big D’s legs, and there wasn’t much we could do about being crammed against the windows.

Coach, a man about Michael’s size, was in the driver’s seat with his seat pulled all the way forward to accommodate D, who didn’t call himself Big D, he said his hiphop name was Lil’ Fila Ice-D T, pronounced as a rhythmic rhyme and spelled as if he had swallowed every popular rapper’s name, chewed them up, and spit them out. His humor was obviously self-deprecating, which is why he started his name Lil’ when everyone knew he looked more like The Fat Boys’s long lost quadruplet. Coach called him Mr. D.

Big D patted his bulging belly and laughed loudly as he squeezed in and pushed Michael against the driver’s side window. D had jogged in a trash bag that morning and not eaten yet that day. As he squeezed into the van, he made jokes about having to cut weight for wrestling after gaining it for football season; in his backpack he carried a Tupperware container full of chips and sandwiches for after weigh-in.

Though large, D was in peak physical condition after a season of football practice; that’s where he had met our wrestling coach, who was also an assistant football coach. Now that football season was over, Coach was focused on wrestling and nurturing our fledgling team.

The Bengal’s co-captain was in the front passenger seat with a stoic countenance that bordered on an annoyed scowl. He was Jeremy Gann, a terse 140 pounder and returning 135 pound state silver medalist who concentrated before a match and relaxed after. His long lanky legs folded atop the glovebox so that he could lean his backrest forward. He never carried a backpack, and was used to feeling hungry for one to two days before a match.

Coach rotated his his squat, acorn-shaped head towards the back of our van, and silently counted to make sure there were 15 kids inside. Perhaps because of his military training, he counted us like a platoon sergeant would count soldiers before and after a battle, silently so they wouldn’t know they were being counted and that there would likely be fewer coming home.

He had been a marine reservist during the 1950’s Korean conflict, though he never went overseas until he wrestled in the 1960 Rome Olympics. Coach was an alternate at 126 pounds, a backup wrestler under the U.S. Army wrestler and American gold winner Doug Blubauh, who, after the Olympics, named World Wrestler of the Year. He won the gold by defeating a three-time world champion from Iran whose name I could never pronounce.

In olympic trials, Doug had barely defeated Coach in sudden-death overtime, and that was back when matches were an Herculean nine minutes of relentless three minute rounds instead of three two minute rounds like in my day. In sudden-death, the first point scored won, and you could forfeit a point for stalling if you weren’t giving your best effort every second. It had taken Doug almost another three minutes of sudden-death to finally take Coach down and win the match. When he won the gold medal a year later, Doug would become world-renowned for pinning all four opponents in the olympics, including the Iranian who had, I heard, never been pinned before. Coach would start a wrestling program at an impoverished rural high school, then accept a role as assistant coach for Iowa State under Dr. Harold Nichols, the legendary coach of Iowa State Cyclones who ran their program for 32 years and brought them to six national championships.

In USA wrestling, Coach Dale Ketelsen was a living legend known, as the one who learned from the best and would have won olympic gold in any other year. At Belaire, he was Coach, head coach of wrestling, assistant coach of football, and the driver’s education instructor.

I glanced past Coach to Big Head Ben, and he gave me a thumbs-up from the driver’s seat of Mr. Abrams’s Astro Van, which Todd had nicknamed The Millennium Falcon because it had so much storage space and there was a knack to starting it that only he and Ben knew.

Todd smirked and saluted. I smirked my best Han Solo smirk and nodded back at Ben and Todd. The Abrams brothers and Michael were the only ones who knew that I had joined the U.S. army’s delayed entry program and requested the 82nd Airborne division. It was probably the most commonly known of what we oversimplified as Special Forces or Special Operations; Sylvester Stallone wore a special forces green beret in Rambo: First Blood; John Wayne wore an Airborne maroon beret in The Longest Day; to us, they were the same.

I turned and crammed my canvas Jansport backpack on the floorboard, then squeezed beside Big D and twisted my shoulder so I could slam the door shut.

As soon as the door clicked closed, Jeremy pulled his Belaire-blue hoodie over his head, reclined his backrest, and stared into the front windshield. I folded my knees onto the back of his seat like he had folded his legs against the glovebox, and set my big feet atop my small backpack. My seat couldn’t recline.

Coach pulled out of Belaire’s gym parking lot and Ben followed. We turned onto Tams Drive towards the Little Saigon shopping mall, and turned right along Florida Boulevard. The road was long road was jammed with traffic lights, strip malls, and po’boy shops, but I had been seeing them since I was a little kid and was more focused on what was happening inside the van.

Jeremy remained silent. The other Bengals cheerfully bantered about how hard it was to skip breakfast and lunch, and veterans told war stories of last seasons tournaments. Big D’s voice was as big as his belly, and he’d interject with improv hip-hop beats and encourage people to enjoy the ride. Miasha said Michael had less rhythm than I did, which was saying a lot because, as I mentioned, I’m one of the whitest people you can imagine; until Eminem came along, some stereotypes were statistically true.

Eight and a half miles later we saw the 39 story new state capital building, an art deco gem built by Louisiana governor Huey Long during the Great Depression, that perched on a slight rise above the Mississippi River levee and surrounded by manicured gardens and a few museums. Capital High was in Capital neighborhood on the other side of the elevated I-110 and I-10 interstates, separated by towering concrete columns that shivered as Big Daddy’s fleet of 18 wheelers rumbled overhead on their way over the half-mile wide Mississippi River Bridge on their way into the concrete veins and arteries of America.

Homeless camps took advantage of the overhead interstates to shield their tents and cardboard huts from rain, and they openly used the cheap addictive drug of choice back then, crack; gun shots were frequent; as a combat veteran, I don’t feel the analogy of a combat zone is hyperbole for the two-mile strip under Baton Rouge’s elevated interstates. Not even Big D ventured there, and he stopped making jokes and peered through the windows.

We passed a new Martin Luther King Junior community center, and Big D woke up and he and Miasha told the same joke that comedians like Richard Pryor and Eddie Murphy had made on television specials: whenever they drove by a street named after Martin Luther King, even they locked their doors.

Coach turned onto North Street and passed the North Street Church, which had a cemetery pot-marked with bullet holes from northern soldiers who reached Baton Rouge after winning battles in Mississippi, an often forgotten part of civil war history that was captured in the fictionalized John Wayne epic, The Horse Soldiers; it was filmed in the former slave plantations around Baton Rouge and Natchez; Big Daddy’s Teamster 18 wheelers had driven Hollywood’s equipment, and Teamster trailers had housed the actors in remote battlefields an hour or so north of downtown Baton Rouge. Many people wondered why John Wayne attended the world premier of The Horse Soldiers in a small, downtown Shreveport movie theater; but we knew that was because Mamma Jean’s family was from Spring Hill, a tiny suburb of Shreveport, and Big Daddy wanted to impress her family by showing that he could get John Wayne to visit them. Those are the type of family stories I never talked about with any of the Bengals other than Ben. Not even Coach knew much about my family history other than the same films and news programs that everyone else had seen.

A few blocks later, Coach turned on 23rd Street and parked parallel on the road alongside Capital High, which didn’t have a dedicated gym parking lot like Belaire did. I flung the door open the moment Coach put the van in park. Jeremy opened the side door, and I squirted out. D finagled himself out the door, and everyone else followed.

I stuck my head in to make sure the van was empty, slammed the door shut, and strapped on my backpack. Coach and Jeremy led us into Capital’s gym. I followed the squad of Bengals, and we walked towards their double doors.

The first thing I noticed was a hand-painted sign above the doors, crisp yellow letters against a black scroll and spelled out: “Welcome to the Lion’s Den.” Inside, the Den was a small windowless building shared with wrestling and basketball. The Lions had spent their afternoon rolling out and taping together three hefty segments of a faded purple and gold LSU wrestling mat. It was centered between their two basketball goals, and framed on either side by worn wooden bleachers.

The mats had been donated to Capital after the LSU Tiger wrestling team disbanded in 1979, one of around 100 collegiate wrestling teams were eliminated after the controversial Title IX law passed; it required equal numbers of male and female athletes in collegiate sports, and the quick solution was to drop unprofitable male-dominated sports with negligible spectators. LSU had donated their mats to schools that wanted to start teams, and that’s how Capital became seeded as the youngest team in Baton Rouge. Our dual meet was always the first of the year, a way for both young teams to warm up for the season without being brutalized by established programs like the Catholic High Bears or Baton Rouge High Bulldogs.

The Lion’s Den walls were painted maroon to match their singlets and warm-up hoodies, but the paint was so faded that the maroon was a close approximation of the faded purple, and the yellow on their murals matched the worn gold. Tufts of gray asbestos dangled from the rafters like the Spanish moss that hung from Baton Rouge’s stately oak trees. The Capital High coach, a mountain of an African American man, was so tall he seemed to brush the asbestos with his mostly bald head.

The Mountain had never wrestled, but he stepped up and took on the daily effort of running a public school team. He lumbered over and smiled and looked down at Coach and extended his right hand. Coach reached his right hand up and grasped The Mountain’s beefy hand, and simultaneously reached his left hand up and clasped The Mountain’s stout forearm with a gripthat crush boulders if it wanted to.

Coach said, “Good to see you, Coach.”

The Mountain beamed and said he was looking forward to our match.

The Mountain, like all Louisiana coaches, knew Coach well. In 1968, Coach was recruited by LSU to form the Tiger Wrestling program; by 1979, he had led the LSU Tigers to be ranked 4th in the nation, defeating even the Iowa State Cyclones in dual meets. But there was no funding to keep the team together after Title IV.

Out of work and without a team, in 1980 Coach donated LSU’s mats to schools around town, took a job as Belaire’s driver’s education teacher and assistant football coach, launched USA into Louisiana, and then started the Belaire wrestling program with his youngest son, Craig Ketelsen, as the first and only wrestler. Craig became Belaire’s first state champion, and everyone Louisiana knew their story. To be a wrestler under Coach was to be welcomed anywhere.

The Lions lined up from 103 pounds to Heavyweight, like a row of purple-hooded Russian nesting Matryeska dolls. All appearing somewhat similar to me compared to the ostensibly more diverse Bengals, especially with those dark maroon hoodies, which I’d later realize were the same maroon as an Airborne beret. Belaire, with our simple bright blue hoodies, lined up in order, too, but without consistency in our uniforms.

I ended up standing next to Hillary; he was a hairy beast.

The joke about Hillary that year, though never to his face, was that he was tough because he was like Sue in Johny Cash’s song, “A Boy Named Sue,” That kid’s dad abandoned his son after naming his son, saying that having a girl’s name would make Sue defend himself against bullies and grow up tough and mean and able to stand up against a harsh world. But Hillary wasn’t mean. He was terse and scowled all the time – at least when I saw him, and given where he grew up that could be expected – but he was never mean.

Hillary was 18 and the oldest wrestler I knew. He was 18 years old at the beginning of his senior year, able to vote in presidential elections and legally buy beer (which still possible in Louisiana because it was the last of the United States to raise the drinking age to 21, and that wouldn’t happen for another three to eight years, depending on how you define it, because state legislators changed the drinking age to 21 but intentionally kept the purchasing age at 18).

There were 19 year old seniors, but that meant they had been held back a year and were ineligible for wrestling. Hillary, as far as I know, maintained the state-mandated C average for variety wrestlers. He was born in mid-October of 1971, a few days shy of being one year before I was born, and he began kindergarten at age 5 and turned 6 a month later. He had always the oldest kid in class, except for when there were kids in his class that had been held back a year or two, which was common in schools without the infrastructure to help all kids succeed.

Hillary was a few fingers shorter than I was, so maybe 5’2.″ But his burly arms were proportionate, not gangly like a lot of growing teenagers, and his thighs bulged with muscles. He looked like a black Wolverine in purple tights instead of the yellow costume of comic books, which was the same yellow of the singlets worn by the Robert E. Lee High Rebels in their oversized school near the gates of LSU.

Hillary had been shaving since the 10th grade. Everyone in the same weight class would stand side by side to weigh in at tournaments, where referees checked for clean-shaven faces and to ensure no one had shaved their legs or arms a few days earlier to make them abrasive. Hillary’s clean shaven face scowled when he stood in line.

I was the opposite. I usually wore a sly grin, though that’s more of a facial feature I inherited from Big Daddy; our cheekbones are high and pull up on the corners of our mouths, making it look like we’re smiling even when we’re not.

My smile was part of my genetic features, but I was also a genuinely cheerful kid who relished practicing and performing sleight of hand magic, and I kept a deck of cards and a coin purse full of 1970’s Kennedy half dollars in my backpack to play with while sitting in class wishing I were outside or on a wrestling mat. My nickname was Magik, with a k, to differentiate it from the LA Laker’s basketball player Magic Johnson and the newly formed professional basketball team, The Orlando Magic, which had just stolen the LSU Tiger’s star player, a towering giant with size 22 basketball shoe named Shaquille Oneal, who would go on to play for the LA Lakers and, in his later years, an international celebrity and sports-center host with custom-made dress shoes. Physically, I epitomized the awkward gangly years of a growing teenager, and I was the youngest senior wrestler in Louisiana.

I was born on 05 October 1972. I began kindergarten in late August of 1977, four years old and a tiny spec of a human being compared to most of the other boys. Had I been born a few days later, or if the cutoff date were shifted two days, I would have been too young to start kindergarten and held back a year to ripen before starting school. That would have led to me beginning my senior year at 17, and by wrestling season I’d be like Hillary and able to vote and buy beer.

Instead, I had turned 17 only a month before I stood facing him the first time, and I walked into The Lions Den as a 5’5″ tall, mid-pubescent kid with disproportionately long arms, wide hands, long knobby fingers, and scuba fins for feet. My toes were bulbous monstrosities hidden inside of size 11 wrestling shoes bulging like a stuffed boudin sausage skin.

My blue singlet was pulled taunt by my long torso. I had negligible underarm hair, and my pale face and shoulders were dotted with bright red pimples that stood out against the blue singlet. My mullet wasn’t for fashion; it hid a few small scars on the back of my head, and one curved 8-inch scar shaped like a backwards letter C; it was, and is, about a finger width thick and bumpy from when the stitches pulled my scalp back on. I had been embarrassed by it since I was a little kid, so I always wore the back of my hair as long as possible; it was a convenient coincidence that mullets were fashionable back then.

My voice had already changed. I had stopped squeaking when I talked, but I still didn’t talk much out of habit.

I was taller than Coach but shorter than Jeremy. I stood beside them with my hoodie lowered so I could see more clearly, and watched the Lions trot onto the faded LSU mats to warm up.

I had never shaved and didn’t need to. The hair on my arms and legs was soft like the fur on a puppy. I never stripped naked to weigh in because I was embarrassed to have only a few scraggly black hairs hidden by my underwear.

After weigh in, the Bengals put our hoodies back on and went into the gymnasium and watched the Lions warm up first. Hillary led the pack. The Lions trotted onto the mat to warm up in a line that began with their 103 pounder and ended with their 275 pound heavyweight, like during weigh in, but this time with Hillary in front. He wore his oversized maroon hoodie low over forehead, and his dark face was hidden in the shadow.

The Lions remained eerily silent as they trotted across the wooden gym floor in single file, like a disciplined military unit efficiently moving a double-time. The small windowless gym echoed with every stomp of their feet, but softened once they trotted onto the faded LSU mats. They jogged in a circle and stomped extra hard on every fourth step to create an intentional rhythm that reverberated in rhythm popular with musicians like George Clinton and James Brown, who said funk is alwys on the one of a four beat: ONE two three four, ONE two three four… The echos reverberated in the small enclosed room and you could feel each one-beat in your chest.

I usually called people in the bleachers spectators, but at Capital they were participants. They stomped in unison with the Lions, and their ramshackle bleachers shook and rattled on every one-beat and added to the overall mystique of being in the Lions Den. Belaire, a football-dominated school, would raise the roof at outdoor football games, but our wrestling meets were filled with a few quiet friends and parents, and I had never saw anything resembling Capital’s crowd at a dual meet.

Every team had its own warm-up ritual, but what stood out about Capital – besides the obvious racial difference – was the contrast of the musical echo of their feet echoing in the gym against their eery silence; no one uttered a word or glanced at us, they just stomped and circled in a gradually diminishing radius. When they finally stopped stomping, they sprawled into a tight circle and landed with their faces close together.

The spectators calmed down and gave the team a moment of silence, and Hillary spoke so softly that I never heard what he told his team as they prepared for battle. For about two minutes, the den became a church. There was be no stomping or squeaks from the stands, just an occasional cough or someone clearing their throat. Hillary looked each soldier in the eye and spoke a few words. Each one nodded back.

When it was Belaire’s turn, we pulled up our blue hoodies and trotted onto the mat silently and without being synced. Jermey led, I was second, and all the other Bengals randomly split into two flocks following two leaders, and each half split again into smaller groups.

We naturally fell into zones of proximal development, small groups of three to five wrestlers who could all learn something from each other. The zone of proximal development is a concept that came from the Soviet Union after WWII, when 30 Million Russians died and left millions of orphans to fend for themselves in massive gymnasiums, without supervision but with researches carrying clipboards recording how kids evolve unconditioned.

Toddlers, I later read, naturally formed small groups where everyone learned a bit from each other; that’s the zone of proximal development. Zones constantly change as people learn, and Belaire’s warm-up routine was never the same twice. We adapted to learn from each other as our skills and maturity evolved.

I don’t know how or why the we naturally evolved into warming up like we did. It probably had to do with Coach having a master’s degree in education theory, and because he told us history of the Russians and how they learned to dominate global wrestling in the 1950’s. When Coach wrestled in the 1960 Olympics, it was the height of the cold war and all the world watched; to put that time into perspective, the American Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba was in 1961, and the Cuban missile crisis that brought the US and Russia to the brink of nuclear war, was in 1962. Coach had learned all kinds of things about Russia while training with the U.S. olympic wrestling team and their army of advisors.

Coach, a man of few words, had mentioned the zone of proximal development once, using fewer words than I just did, and the Bengals fell into the habit organically. During our warm ups, he stood off mat and in the sidelines while each group methodically drilled single leg shots, doubles, stand ups, and sprawls, the foundation blocks of any great wrestler.

Weight classes were an obvious influence on our groups, but so were interpersonal dynamics. Ben was in my zone, and so was Big D; they stayed together because only Ben was big enough for D to toss around without inflicting friendly-fire damage. So was Michael; he and I were similar in styles, yet different enough to continuously learn from each other, which a hallmark of the zone of proximal development. And, he, Ben, and I had realized we could topple Big D if all three of us banded together.

We finished warming up when Jeremy said so, and gathered beside Coach in Belaire’s corner of Capital’s mat. The referee stepped into the center of the mat and called the captains to join him.

Belaire was the only team in Louisiana with co-captains, and no one had seen two wrestlers step onto the mat when a captain was called. Hillary cocked his head and stared at both of us with stoic indifference, more like he processing new information rather than pondering why there were two of us on his mat.

The referee spoke softly to us and reminded us to wrestle fairly. Jeremy and Hillary slapped hands in a modified handshake to show the spectators we would take the message back to our teams. I held out my hand, but Hillary turned before slapping it and I don’t know if he had noticed. I glanced around, and Jeremy was already half way back to Belair’e corner.

I jogged to catch up. Jeremy sat beside Coach and I stood by the team, because state rules restricted the number of people on the mat corner to two.

Matches began at 103 pounds and proceeded up each weight class. I began warming up when the 129 pounders shook hands, because you never know how quickly matches can end and there was only the 135 and 140 pound match before mine. Most wrestlers began warming up only when the weight before them began, but, Hillary warmed up at the same time that I did. He slipped a set of large headphones under his hoodie and stepped into a corner away from spectators.

I put on my small foam headset and pushed play on my Walkman’s wrestling mix tape, a collage of 1980’s mid-paced heavy metal you could skip to, like Metal Health by Quiet Riot, and the more mellow and melodic Lunatic Fringe by Red Ryder, a song from the soundtrack of 1985’s wrestling film, Vision Quest.

Hillary and I warmed up the same way, though I don’t know what he listed to on his Walkman. We began whipping our arms around our chests and slowly pumping our legs up and down with oversized steps. Then we shook our heads and hands and feet faster, breathing in deeply and exhaling slowly. Hillary never glanced my way.

Hillary began doing jumping jacks and squat thrusts. I skipped a rope to raise my heartbeat and break a thin sheen of sweat that meant I’d be tapped into fat energy, just like the kid in Vision Quest did and what I had read in some of the olympic training guides scattered across Coach’s desk at Belaire. Hillary and I both warmed up at a pace we could probably keep up for hours without depleting energy.

Jeremy pinned his Lion, which triggered Hillary and me to move towards the mat. I donned the state mandated headgear over my ears and struggled for a few seconds to adjust the vinyl straps, which were still a bit stiff after being left motionless in Belaire’s supply closet all summer.

I barely understood the muffled sound of the ref calling us, but I knew the routine and what to expect. I trotted over and stood in the center and leaned forward to face Hillary. The whites around his dark eyes were barely visible in the shadows of his face mask. I briefly wondered how he saw anything through those holes, then took a deep breath and slowly exhaled and let my breathing do what it needed to do. We squatted into our stances and slapped our right hands as a modified handshake to acknowledge we were ready.

The referee blew his whistle and I instantly shot a low single. Hillary sprawled, cross-faced the hell out of me, spun behind, and drove my face into the mat.

I didn’t have time to process what happened before he threw in a half-nelson and turned me to my back. Hillary rose up on his toes and thrust all of his weight onto my chest, and he cranked up on my head with his burly arm; my nose pressed into his hairy armpit, and my eyes were wide open and staring at the asbestos dangling from the roof rafters.

I could feel blood gathering in my nostrils, but there was enough air flowing to smell his dank underarm odor. My mind was whirling and overwhelmed with pain in my nose, strain in my neck, and pressure on my chest; his Brillo-pad chest hair rubbed my bald and pimply chest raw.

I remember his dank odor, but not feeling my shoulders touch the mat. I was so overwhelmed that I didn’t snap out of it until I heard the referee slap the mat next to my shoulders and blow his whistle in our ears to signal a pin.

We stood back up in the center, and the referee held Hillary’s hand up in the air. Even with my headgear on, the applause from Capital’s bleachers was deafening. I could feel the reverberations in my chest as they stomped their feet and hollered. I was dazed. I glanced at the basketball scoreboard used as a timer. Hillary had pinned me in 22 seconds; it had taken me longer to adjust my headgear.

Hillary would make more sense in my mind after 2008, when Malcomn Gladwell published a book that summarized what happened. In “Outliers: The Hidden Secrets of Success,” Gladwell began with an obscure Canadian research study that looked into why professional hockey players were overwhelmingly likely to be in January to March. It wasn’t astrology. Like with Hillary and me, an arbitrary age cutoff allowed those kids to begin competing in hockey almost a full year sooner than their peers; for a four to five year old, that’s a 20% linear time jump on an exponential scale for strength and mental experiences curve. Over time, those differences accumulate with all skills; those who began with an advantage are usually given more, and those who begin with a relative disadvantage are given less.

Gladwell said it was an example of The Matthew Effect, a term coined by a criminal sociologist who predated Gladwell and used The Matthew Effect to explain why crime-ridden areas deepen poverty and wealthier areas springboard success, taking the term from the New Testament Book of Matthew, 13:12, where Matthew quoted Jesus as saying something like:

“Whoever has shall receive more, and whoever has not shall have even that taken away from him.”

The only thing Malcomn Gladwell identified as being within one’s control was determination and perseverance, and even that was influenced by people like our parents, teachers, peers, and coaches.

If I had anything besides Coach to balance Hillary’s birthdate advantage, it was what my teammates called tenacity. I had lost all 13 matches in the tenth grade, my first year and when I was only on the team for a month (in a sense of irony, I was suspended from school and made ineligible for sports because I parroted the word “nigger” when joking with Miasha and Micheal in the hallway, who had just called me “a little white nigger” because I spoke like a coonass redneck, which would have been fine to say at Belaire, because almost half of us were coonass rednecks). But, Coach let me train with the team as what he called a Red Shirt, a term from football that lets kids wear red shirts and practice with the team until they’re big enough to compete.

I ended my junior year with a winning record of 54-38, more than twice the number of matches Jeremy and other good wrestlers because of seeding brackets that strive to prevent the top two wrestlers from facing off until finals, stacking the tournament like The Matthew Effect and resulting in the lowest seeds bumping down to the looser’s bracket and having to claw their way up again. I had simply out-wrestled better wrestlers by being persistent and wrestling more often.

I returned to our corner. Coach grasped my right hand in his and squeezed my left tricep in a vice-like grip with his left hand, looked up into my eyes, and sincerely said, “Good job, Magik,” just like he had 105 times in the past year and a half.

I had more sweat from warming up than wrestling, but I still accepted the hand towel Jeremy handed me to wipe off sweat. I took it and stepped behind him and Coach. Rules only allowed two people on the corner of the mat, so I sat on the front row bleachers and in a spot the other Bengals had saved for me. I leaned forward to watch the next match and dabbed my nostrils.

Hillary strolled walked back to Capital’s corner and began prepping their 152 pounder for battle; that wrestler pinned Miasha early in the second round with the same half-nelson Hillary had used on me. I don’t recall our 158 pound match. Todd panicked when the 165 pound Lion smothered his mouth and nose with a headlock towards the end of his first round; still gasping when he sat in the bleachers, he fumbled through his backpack for an inhaler, and through wheezing voice told me it was his final match. Steve and his wrestler went into overtime, and Steve, though gasping for breath, manhandled his Lion into a takedown. Big Head Ben fizzled out and was manhandled towards the end of the second round and pinned with only six seconds remaining.

After Capital’s heavyweight pinned Big D in the third round, both teams lined up and walked beside each other, slapping hands to congratulate each other and completing the circle from when team-captains shook an hour and a half before.

I don’t recall the overall team score, but Capital won about 70% of the matches. From Coach’s perspective, it was a victory for Belaire. He reminded us that this was the first time in our history that we had a full squad, and said that momentum carries teams forward.

15 of us loaded back into Coach’s van, and the other wrestles filled the Abrams’s Astrovan. It was November, so days were short and the ride back along Florida Boulevard was illuminated by street lights and traffic signals and strip mall parking lights that strobed through our van’s windows. All of the windows were cracked open to allow air flow and to flush away the stench of our sweaty post-match uniforms.

Everyone except me was laughing and chatting with each other and talked about what they’d do differently next time. Big D quipped that he couldn’t help me because he blinked and missed my match; I said he was probably too busy eating a sandwich to see anythings without mayonnaise on it. Michael studied; he had been pinned in the second round by a returning city champion, and had a test or something the next day, and he was probably going to quit the team and focus on his ROTC scholarship so that he could go to college at West Point, like his dad had.

The Bengals bantered and I slid into deep thought. Absentmindedly, my right hand reached up along the van’s window and to the back of my head, where my fingers traced the biggest scar across the back my scalp, a habit I’ve had since I was at least five years old. The scar’s skin is slippery, and my fingers fit it’s width and slide along the backwards C shape and over the bumps from where stitches bunched the skin and ridges formed. My two first fingers followed the scar up and down until I caught myself doing it and brought my hand back along the window and into my lap.

I grasped the towel and rolled it to hid the dabs of dried blood that had become darker than Capital’s hoodies. I stared at the lights flickering past us at 45 miles per hour. A thought popped up, the one that had probably arisen before or while I was lost in my scar, and probably because of my sore nose and bloody towel. The first time my nose bled was my first match in the 10th grade, at Belaire’s Thanksgiving tournament, a tradition Coach brought from Iowa that was a way for new wrestlers to get practice with a small, one-day tournament that was sparsely attended due to family obligations; though he never said so. I was 121 pounds wrestling at 123 and had shot first, just like against Hillary, and that kid, who was also African American and whose armpit smelled similar, sprawled and crossfaced me and threw in a half just like Hillary had.

The difference between Hillary and that wrestler was that he was only marginally better than I was, and he didn’t know how to pin someone with the half; but, I choked on my blood and panicked when I couldn’t breathe, and I forced my left shoulder to the mat to end our match.

The referee raised his hand and I walked off the mat and Coach shook my hand and said, “Good job, Magik,” but I knew better. He handed me a towel and taught me to hold pressure on my nose without looking at the towel for at least the length of a full six minute match, and I spent the entire time trying to convince myself that I was pinned. But I finally admitted that I had quit and committed hari-kari. I would never quit again, but I would lose the next 12 matches before telling Michael and Miasha that I would gladly be an honorary nigger.

I matured a bit by the beginning of my 11th grade year, and I rejoined the team and vowed to never quit again, more from bravado and parroting Karate and Boxing movies of the era. I had adhered to that promise and it had become a habit; I hadn’t quit against Hillary, he was just that good. I was confused: ever since my first match, I had never been beaten that badly before and had assumed it was impossible to not last until at least the second round.

Coach turned away from Florida Bulevard by the strip mall filled with bright lights from the Vietnamese business district, it had hand-written signs illuminated by flood lights and advertised things like: “Bon-Mi, a Vietnamese po-boy.” We were almost home. I stopped thinking about my match and began getting ready to exit the van’s door like I was jumping from the side doors of a C-130 aircraft with 63 airsick and heavily armed paratroopers anxious for me to get out of the way.

We pulled into our gym’s parking empty parking lot. Parents were parked under the lights and waiting to take their soldiers home. Everyone piled out, Big Head Ben Abrams let a few guys out and said he’d take the rest home. Jeremy, Michael, and Miasha walked home. Big D’s equally large parents picked him up in a van almost as big as Belaire’s; I never learned what they did for their livelihood to need such a monster of a van, or why we couldn’t use it for dual meets.

I waited until all the Bengals left, strapped on my backpack, straddled my motorcycle, donned my helmet, turned the key, and pushed the ignition. The light illuminated Belaire’s two-story dark red brick wall of our relatively large gym.

Coach waved from beside the big Ford F150 he used to haul mats between schools for tournaments. I waved back and rode out of the parking lot and onto Tams and towards home. Coach stayed; he was like the army’s pathfinders in Vietnam, the guys who parachuted into dense jungles with extra padded combat gear and cleared trees for others to follow, then guarded the area when helicopters picked the others up and took them home. Coach was always the first one to arrive, and the last one to leave.

I was focused on riding and I didn’t glance back to see when Coach left for his home. I knew he’d be at Belaire when I showed up the next morning.

Go to the Table of Contents

- From “Hoffa: The Real Story,” his second autobiography, published a few months before he vanished in 1975 ↩︎