A Part in History, Part I

But then came the killing shot that was to nail me to the cross.

Edward Grady Partin.

And Life magazine once again was Robert Kenedy’s tool. He figured that, at long last, he was going to dust my ass and he wanted to set the public up to see what a great man he was in getting Hoffa.

Life quoted Walter Sheridan, head of the Get-Hoffa Squad, that Partin was virtually the all-American boy even though he had been in jail “because of a minor domestic problem.”

– Jimmy Hoffa in “Hoffa: The Real Story,” 19751

I’m Jason Partin. My father is Edward Grady Partin Junior, a former drug dealer who was released from prison in 1987 and is currently a public defense attorney in Louisiana. My grandfather was Edward Grady Partin Senior, the Baton Rouge Teamster leader famous for infiltrating Teamster president Jimmy Hoffa’s inner circle in 1962, and what New Orleans district attorney Jim Garrison called “a person of interest” in President Kennedy’s assassination.

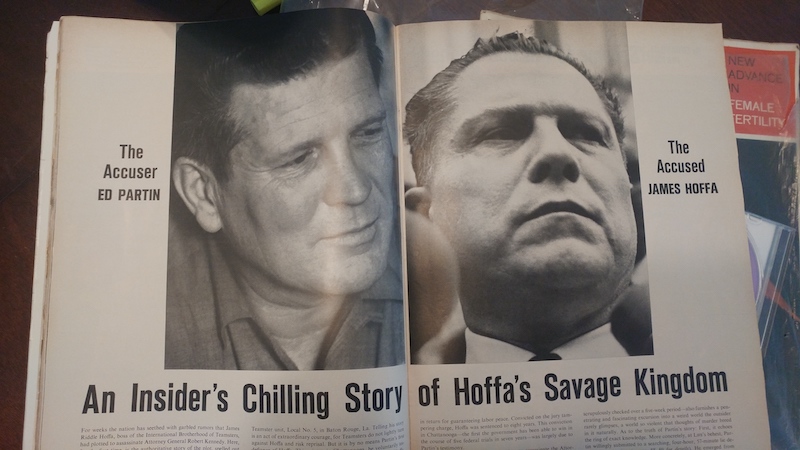

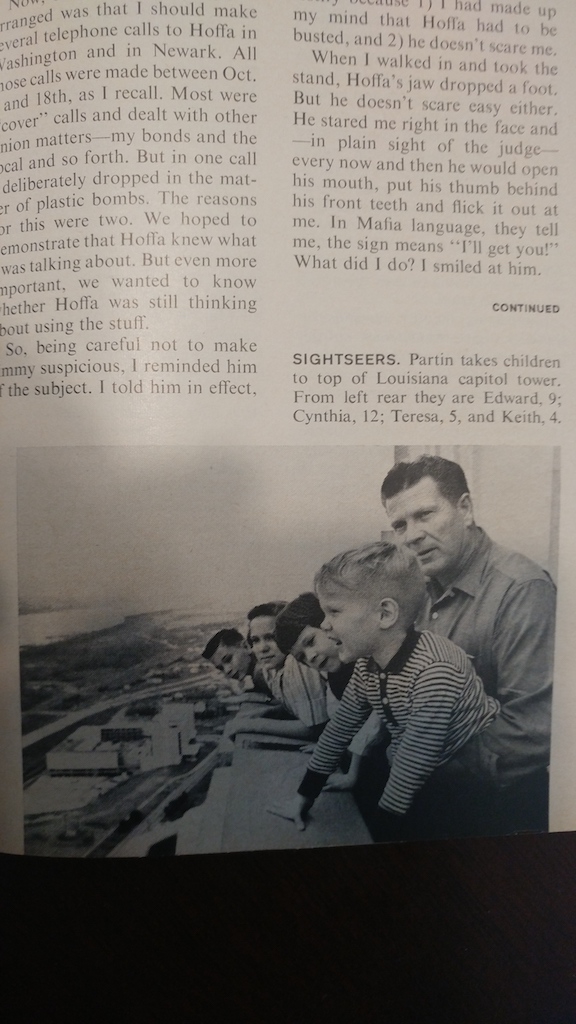

Everyone in Baton Rouge called my grandfather Big Daddy. He ran the local Teamsters for thirty years and was famous even before he testified against Hoffa. That trial was followed daily across America, and after the jury convicted Hoffa soley based on Big Daddy’s testimony, U.S. Attorney General Bobby Kennedy and FBI director J. Edgar Hoover polished the image of their witness by plastering Big Daddy and my family across national media and dubbing him an all-American hero and us an all-American familh.

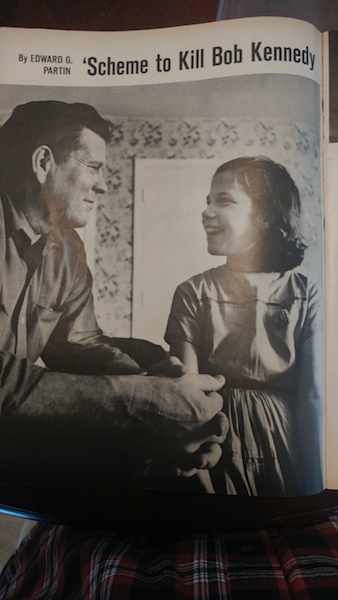

Big Daddy was portrayed as a rugged family man who saved Bobby’s life by thwarting an assassination plot by Hoffa, and who helped America change a corrupt union. His fame was flamed when Bobby was shot and killed by the redundantly named Sirhan Sirhan in 1968, and again after Hoffa was released from prison and famously vanished from a Detroit parking lot on 30 July 1975. Because Big Daddy was so big and tough and handsome and charming, a man Hoffa described by saying, “Edward Grady Partin was a big, rugged guy who could charm a snake off a rock,” America swooned when they saw his subtle smile and heard his smooth southern drawl.

In 1983, when I was in middle school and helping my dad tend his marijuana fields, Big Daddy was portrayed by the famous actor Brian Dennehy in the anticipated two-part film about Hoffa and his battle against the Kennedys, “Blood Feud.” America knew how Big Daddy and Hoffa looked and sounded, so producers found actors that matched what people expected.

Brian was less famous than my grandfather back then, but he was an up-and-coming star known for his “rugged good looks,” green-blue eyes, and charming smile. Robert Blake was already famous, a child actor, army veteran, and adult star known for a career that was “one of the longest in Hollywood history.” Blake coincidentally looked like the intense, square-jawed Hoffa, and he won an academy award for “channeling Hoffa’s rage.” A daytime soap opera heartthrob portrayed Bobby Kennedy in a relatively smaller role, because the film was focused on Hoffa and Big Daddy. The film emphasized a scene where Blake, portraying a scene from FBI records where Hoffa quietly looked into space and mimicked tossing a bomb into Bobby Kennedy’s home, then asked Big Daddy to get military plastic explosives from his contacts with the New Orleans mafia; Dennehy, under Hoover’s guidance, calmly refused, saying he wouldn’t kill Bobby’s children just for Hoffa’s benefit. Big Daddy’s reputation as an all-American hero continued, even though he was in prison by then for a range of charges worse than anything Hoffa ever pondered; he thought Brian Dennehy did a fine job portraying him, regardless of what really happened.

(Coincidentally, Brian’s breakout role came that same year, when he starred alongside Sylvester Stalone in another film with blood in it’s name, “Rambo: First Blood.” Brian portrayed a Korean War veteran and the rugged small mountain-town sheriff who led the hunt for Rambo, a former special forces Vietnam veteran wandering America with PTSD. Brian got his start portraying Big Daddy, and would eventually try to fool America and increase his fame by claiming he was an actual combat veteran, stealing valor from those who were. After admitting his mistake, he became one of the most celebrated actors of his generation. He died in 2020 during the Covid-19 pandemic, a month before his final film debuted online, in which he ironically portrayed an aging Korean War veteran in modern times. Robert Blake would be charged with murdering his second wife, file bankruptcy, and died in 2023 at age 89; his list of films, television, and plays on Wikipedia takes several pages to scroll through. I never followed the daytime soap opera’s career.)

In 2019, Big Daddy was portrayed by the burly actor Craig Vincent in Martin Scorcese’s opus about the Jimmy Hoffa and the American mafia, “The Irishman.” Scorsese raised $270 Million and hired a long list of Hollywood’s most famous actors know for gangster films, like Al Pacino, Robert DeNiro, Joe Pesci, and about a dozen others. Craig, a 6’5″ barrel-chested brute on film but kind and cheerful person in life, as chosen to portray Big Daddy because he had worked with Scorsese before, portraying a big, brutal thug alongside Pacino and Pesci in Scorcese’s Las Vegas mobster film, “Casino.”

Scorsese based “The Irishman” on a memoir called “I Heard You Paint Houses,” co-written by one of Big Daddy’s peers, Frank “The Irishman” Sheenan, a former WWII combat infantryman, Teamster leader, and mafia hitman who spent 13 years in prison before writing a memoir that says he killed Hoffa. To “paint a house” was mafia code for killing someone by painting a wall red with their splattered blood, and apparently it’s what Hoffa said to Frank when they met and Frank became a Teamster leader under Hoffa, like Big Daddy had in the 1950’s.

Frank knew Big Daddy well. He wrote extensively of Big Daddy, President Richard Nixon, and Audie Murphy, America’s most decorated combat veteran back then, with 268 confirmed kills in WWII, a star in almost 40 action films, and the second most visited tomb in Arlington Cemetary after President John F. Kennedy. Big Daddy was being courted by Nixon to free Hoffa, and was a suspect in Audie’s death, but those parts were omitted from The Irishman film because Scorsese said he was making an entertaining film to sell tickets, not a documentary. He focused on Frank killing Hoffa, and reinvented Big Daddy as “Big Eddie,” a northeast Italian brute who matched Craig’s Italian-American complexion and accent.

Craig’s 20 minute role was edited down to five minutes so that Scorcese could squeeze him in to a film that was already a whopping 3 hours and 24 minutes long, more than the patience of even the most dedicated film aficionados. To convey the bigger picture, Scorcese lowered a wide-angle camera to peer up at all the famous actors with Big Eddie standing behind them, his size exaggerated by the camera angle, looming over Hoffa and Frank but with them unaware that Big Eddie was working with Bobby Kennedy and J. Edgar Hoover and steering the plot.

The Irishman was released in theaters the summer of 2019 with lines of people waiting to see it. When the Covid-19 pandemic shuttered theaters globally in 2020, Netflix bought rights to The Irishman and it set global streaming records. For the next two years, hundreds of millions of people all over the world saw a fictionalized glimpse at my family’s part in history.

I had chatted with Craig a few times when he researching his role. He had called my uncle, Kieth Partin, first, because Keith was president of the Baton Rouge Teamtsers like his father, Big Daddy, had been. He tried to speak with my great-uncle, Doug Partin, Big Daddy’s little brother who had been the Baton Rouge president for thirty years after Big Daddy went to prison in 1980, but Doug was aging in a Mississippi veteran’s convalescent home and focused on Big Daddy killing Audie Murphy. (Most historians say it was a faulty aircraft, not Big Daddy, that killed Audie and the other four passengers.) The Teamsters seemed to be a family business, Craig noted; James R. Hoffa Junior was the president of the international Teamsters, so Craig was probably right.

Craig was the first person I had spoken with who had dug into history focused solely on my grandfather. He knew the facts, but wanted to know which personality traits and motivations of Big Daddy. I couldn’t help him. I was too close to Big Daddy and my family to see us from an outsider’s perspective, I said. But Craig planted a seed that sprouted when The Irishman fictionalized Big Daddy, and grew when I sheltered at home for the two years of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Big Daddy died my senior year of high school, a few months before I left Louisiana for the army and fought in the first Gulf war of 1990-1991, and two weeks after Hillary Clinton broke my left ring finger just proximal of the middle knuckle, which healed askew and to this day my two middle fingers are permanently spread like the split-finger salute Leornard Nemoy made famous as Dr. Spock in the Stark Trek. Coincidentally, or perhaps not, in the early 2000’s I’d invent a series of medical implants that healed small bones and are listed under either Jason Partin or Jason Ian Partin in the US Patent and Trademark Office website and describe small screws connected by tiny springs that reach across fractures and compress bones together to accelerate healing; when I presented to investors, I held up that hand to show what happens to bones that heal askew, though I never mentioned my grandfather and how I broke my finger. But it was on my mind every time, and the memory is as fresh in my mind today as it was then.

Big Daddy’s funeral was on 11 March 1990, and Hillary broke my finger in the Baton Rouge city wrestling tournament finals on 03 March 1990. Big Daddy’s funeral was covered by national news and still online with the NY Times and LA Times, where I was listed simply as one of his five grandchildren. My match against Hillary is listed in archives of the Louisiana High School Athletic Association, LHSAA.org. I was listed as Jason Partin, winner of the silver medal at 145 pounds.

The Hillary Clinton who broke my finger was not Hillary Rodham Clinton, who was then the first lady of Arkansas governor Bill Clinton. He became president in 1992, leading that Hillary Clinton to become a household name, presidential candidate in 2008, and the United States Secretary of State under President Barak Obama from 2009 to 2013. The Hillary who broke my finger and won the gold medal in 1990 was the returning three-time undefeated Louisiana state champion at 145 pounds, and winner of the Baton Rouge city tournament gold medal after he pinned me one minute and twenty seconds into the second round.

The first time I remember seeing Hillary was a Wednesday evening on 08 November 1989. I must have seen him before, because he was captain of the Capital High School Lions, an inner-city public school a mile from the new Baton Rouge state capital, under the intersections of Interstate 10 and 110 in a pocket of urban poverty. Their team was 100% African American and they ritualistically wore dark maroon hoodies that shadowed their faces. I was a caucasian kid from Belaire High School who didn’t realize I was seeing history unfold, but I recall our first match so well because of my eventual broken finger and the seven beatings Hillary laid upon me the rest of that season.

That Wednesday was the first dual meet of Louisiana’s 1989-1990 wrestling season. The Belaire Bengal wrestling team piled into the sliding side door of Belaire’s big blue sport van immediately after school let out. I stood by the door with my hand on the handle. I was waiting for our 275 heavyweight, a big bellied rapper named Dana “Big D” Miles, to squeeze in to the bucket seat beside Michael, our 135 pounder and Belaire’s Junior ROTC captain, an alert and cheerful wrester whose father had been one of only a handful of African American special forces officers in the Vietnam conflict. (The conflict ended in 1975, the same year Hoffa vanished, and by 1989 many of the veterans in Belaire subdivision had 12 to 15 year old kids in school; to my knowledge, I was the only son of a drug dealer.) Michael and I were each the size of one of Big D’s legs.

Coach, a man about Michael’s size, was in the driver’s seat with his seat pulled all the way forward to accommodate D, who laughed and patted his bulging belly as he squeezed in. He had jogged in a trash bag that morning and not eaten yet that day, and made jokes about having to cut weight for wrestling after gaining it for football season. His jokes were delivered in a hip-hop rhythm intentionally mimicking to the then-famous duo, The Fat Boys, in self-depricating self-awareness that was so obvious we all loved him for it.

The Bengal’s co-captain, a terse 140 pound returning state silver medalist named Jeremy, was in the front passenger seat with a stoic countenance and his long lanky legs folded atop the glovebox so that he could lean his back rest forward. His family had moved to Belaire from a wrestling-focused town in Pennsylvania when he was in the 10th grade, and he instantly dominated Belaire’s fledgling team and was our captain the year before. Coach, a former marine, counted to make sure there were 15 kids inside. I glanced around to ensure no one was being left behind, a habit I picked up from Coach the year before, then sat beside Big D and twisted my shoulder so I could slide the door shut.

We pulled out of Belaire’s gym parking lot and turned onto Tams Drive towards Florida Bulevard, the long road through town that predated the interstates and was jammed with traffic lights and strip malls. The Bengals cheerfully bantered about cutting weight and told the handful of freshmen and new wrestlers war stories from the year before. Jeremy pulled his hoodie over his head, reclined his backrest, and stared at road ahead. I folded my knees onto the back of his seat like he had folded his against the glovebox.

Eight and a half miles later we saw the 39 story new state capital building, an art deco gem built by Louisiana governor Huey Long during the Great Depression perched on a slight rise above the Mississippi River levee and the old state capital. Coach turned onto North Street and passed the North Street Church, which had a cemetery potmarked with bullet holes from northern soldiers who reached Baton Rouge after winning battles in Mississippi. Baton Rouge was riddled with souvenirs of the civil war; a state park north of us was Fort Pickens, site of a year-long seige and the longest battle of the civil war, and to this day civil war enthusiasts use metal detectors to scour the thick pine forest around the battlefield and find bullets and cannonballs and occasional rusty but coveted muskets.

The bullet holes along North Street reminded us of how recent the civil war had been, but as teenagers we didn’t give it much thought. Few people appreciate their home town, and I was no exception, especially because we were focused on our first match of the season, and I was intent on my first time representing the Bengals as co-captain.

We passed under the cars and trucks rumbling across the elevated I-10, and a few blocks later we turned on 23rd Street and parked parallel alongside Capital High. I flung the door open the moment Coach put the van in park, and was practically squirted out by the pressure of Big D against my left arm. I stood by as everyone piled out, stuck my head in to make sure the van was empty, and slammed the door shut and followed the team. Coach and Jeremy led us into Capital’s gym.

I had never been to Capital before. It was in what most people considered an undesireable and crime-ridden part of town, separated from the gardens and museums around the capital building by I-110. Like a lot of downtowns in the 1960’s and 70’s, the new interstates split neighborhoods and created pockets of poverty that persist today and ironically have streets renamed after Martin Luther King Junior, a point nailed home by practically every comedian from Richard Prior to Eddie Murphy. President Eisnhower, a WWII general with his face immortalized on old silver dollars, spearheaded the American interstate system and modeled it after Germany’s Autobahn, which had allowed Hitler’s army to quickly mobilize and dominate Europe’s relatively sleepy forces. The interstates shifted American commerce shipping from railways to interstates, and coincided with the influence and power of Jimmy Hoffa’s 2.7 Million Teamster truck drivers who delivered almost every product on every store shelf in every town in America. I-10 was one of the first, staring a few miles from Florida’s Atlantic coast, passing through the port of New Orleans and Baton Rouge, and stretching more than 3,000 miles before ending within sight of the Pacific coast and the Santa Monica pier. A few years after my first trip to Capital nighborhood, soon after the internet began and www.Mapquest.com was launched, I plotted a map from Capital High to Santa Monica and it was only three lines: get onto I-10, go 3,384 miles, and exit onto Santa Monica Boulevard.

I-110 was a short jaunt built to access the Baton Rouge airport, the one where Lee Harvey Oswald trained under the alias Harvey Lee, and the relatively new row of petrochemical plants north of the airport. Big Daddy had been influential in having I-110 built, and his Teamsters bypassed the airport, rail lines, and ships of Baton Rouge’s Mississippi River port to truck processed oil and plastics past the state capital and onto I-10 and into the veins and arteries of America.

The consequence to neighborhoods like Capital were universally considered a net positive impact on America’s economy, and as a token gesture streets were renamed after Martin Luther King, which led to generations of comedians like Richard Prior and Eddie Murphy quipping that every Martin Luther King Junior Bulevard was in the most derelict parts of cities. Baton Rouge didn’t rename streets, but a MLK community center was put near the intersection of I-110 and I-10. I never went to the center, and I grew up feeling connected to the endless stream of 18 wheelers rumbling across the elevated interstates that created shadows over downtown homes, believing the eminent domain was a good thing. I never asked anyone from Capital what they thought.

The first I thing I noticed was a hand-painted sign above Capital’s double gym doors in large yellow letters and against a black scroll that said: “Welcome to the Lion’s Den.” Inside, they had laid out a faded purple and gold LSU wrestling mat donated after the team disbanded in 1979, one of around 100 collegiate wrestling teams that shuttered like movie theaters during Covid after the controversial Title IX law passed and required equal numbers of male and female athletes in collegiate sports. The quick solution was to drop unprofitable male-dominated sports with negligible spectators, like wrestling, then slowly start building women’s sports teams.

Coach, a former olympian and assistant coach at Iowa, had been recruited to start LSU’s program in 1968, the same year Martin Luther King Junior was assassinated by a lone sniper in Atlanta in a way so similar to President Kennedy’s murder that they share a congressional assassination report. Though Coach led the LSU Tigers to be ranked 4th in the nation, defeating even legendary teams like Iowa in dual meets, the Tigers became a casualty of Title IV. Coach donated their mats to schools around town, took a job as Belaire’s driver’s education teacher in 1980, and started our wrestling team with his youngest son, Craig Ketelsen, as our first wrestler and then our first state champion, who today is on the board of the Louisiana High School Athletic Association that keeps records of tournaments like the one where Hillary would break my finger four months later.

When Craig was at Belaire, Coach raised enough money to replace Belaire’s mats donated mats with a new blue and orange mat to match our uniforms, but Capital hadn’t raised enough funding to replace the old LSU mats. Their gym walls were painted maroon to match their singlets and warm-up hoodies, but the paint was so faded that the maroon was a close approximation of the faded purple, and the yellow on their murals matched the worn gold.

Their gym rafters had tufts of gray asbestos dangling like the Spanish moss that hung from Baton Rouge’s stately oak trees on the grounds of schools with names like Glen Oaks, and the former slave plantations like White Oak and Oak Alley. The windowless and small gym that was shared with wrestling and basketball trapped the smell of their sweat. They had no air conditioner to help dry out the walls and wooden bleachers, and I could smell hints of mold, a putrid odor familiar to all of us in the hot and muggy deep south. Their locker room was a windowless prison cell that made my mild claustrophobia spike and my heartbeat accelerate, especially with the suffocating smells preventing me from breathing deeply.

We stripped down to our singlets in their locker room and the referee checked our weight, then we donned our hoodies and gathered in the gym on our side of the mat. No one from Belaire venture into Capital neighborhood, so we had no parents or spectators in our corner.

Capital’s spectators in the stands wore the same green, red, and yellow colors of Capital’s murals. I had yet to learn about Ethopia’s Lion of Juddah on their green, yellow, and red flag that symbolizes strength and pride in Africa, and I thought the Lions were paying tribute to the colors of New Orlean’s Zulu parade. By my high school prom a few months later, I would evolve to think The Lion’s Den was named from the Book of Daniel, where Daniel was tossed into a den of lions to test his faith, because many wrestlers, myself included, fasted to cut weight before facing a pack of lions, just like Daniel had fasted so he could settle his mind and listen to God. Their motivations to paint the murals were probably a combination of reasons lost to those parents who filled the bleachers that day and watched their children’s first match of the season.

Hillary led the pack. The Lions trotted onto the mat to warm up in a line that began with their 103 pounder and ended with their 275 pound heavyweight, like a line of purple hooded Russian Matryoska dolls, but with Hillary moved to the front. He wore his maroon hoodie low over forehead, and his dark face was hidden in the shadow. The shadow, and his broad chest pushing against his maroon hoodie, demanded attention. Had he been a professional television wrestler trying to create an intense image, he couldn’t have done better than that tight fitting maroon hoodie and the shadow obscuring his face.

The joke about Hillary, though never to his face, was that he was tough because he was like Sue in Johny Cash’s song, “A Boy Named Sue,” the one written in the 1960’s by the poet and cartoonist Shel Silverstein about a boy whose dad who abandoned his family after naming Sue, saying that having a girl’s name would make Sue defend himself against bullies and grow up tough and mean and able to stand up against a harsh world.

But Hillary wasn’t mean. He was terse and scowled all the time, but he wasn’t mean. He was an focused athlete, putting in extra hours by running up and down the 39 flights of stairs in the state capital on weekends, doing pushups while other kids sat in bleachers, and staring intently at every match of his Lions he oversaw, learning from nuances most of us missed. He was the oldest wrestler I knew, already 18 years old in high school and able to vote in presidential elections and legally buy beer (still possible in 1989 because Louisiana was the last state to raise the legal age to 21).

I would later hear that Hillary was born in mid-October of 1971, a few days shy of being one year before I was born, and that he began kindergarten at age 5. That meant turned 6 a month later, the oldest and biggest kid in kindergarten. He hadn’t grown taller since the 11th grade, and by the time we were seniors in high school all of his calories went towards building stronger, denser muscle.

He was 5’4,″ and his burly arms were proportionate, not gangly like a lot of growing teenagers. His thighs bulged with muscles, and his lats were a hands-width wider than his narrow waist. To fit into Capital High’s skin-tight maroon wrestling singlet, he had to wear a larger size than his lean stomach needed; it was taut across his chest but hung in loose folds around his waist.

Hillary had been shaving since the 10th grade. Everyone in the same weight class would stand side by side to weigh in at tournaments, where referees checked for clean-shaven faces. Unscrupulous wrestlers shaved a few days before a match to make their chins and arms abrasive, like course sandpaper, but Hillary shaved his face smooth each morning before competing. He kept his body hair natural, though, probably because his forearms were covered in Brillo pads like we used to scrub cast iron pots and his chest hair was already a mat of thorny spines that hurt like hell when he put all of his weight into pinning you. He was so strong and skilled he didn’t need to cheat. His face scowled when waiting in line with the rest of us to weigh in, and he rarely spoke to us; Jeremy was loquacious compared to Hillary.

I was the opposite. I usually wore a sly grin, though that’s more of a facial feature I inherited from Big Daddy; our cheekbones are high and pull up on the corners of our mouths, making it look like we’re smiling even when we’re not. (Brian Dennehy did a fine job of mimicking that smile in Blood Feud, and it would become his signature look in the following decades, but for me and a few of my cousins it came naturally.)

My smile was part of my features, but I was also a genuinely happy kid, emotionally. Physically, I epitomized the awkward gangly years of a growing teenager. I was the youngest senior wrestler in Louisiana.

I was born on 05 October 1972, and I began kindergarten in late August of 1977, when I was four years old. I was always the youngest, smallest kid in class. Had I been born a few days later, or if the cutoff date were shifted two days, I would have been too young to start kindergarten and held back a year to ripen before starting school. That would have led to me beginning my senior year at 17, and by wrestling season I’d be like Hillary and able to vote and buy beer. And, knowing what I know now, I would have been 5’11” and around 190 lean pounds of muscle; instead, I walked into The Lions Den that Wednesday as a 16 year old, 145 pound, 5’5″ tall, mid-pubescent kid with disproportionately long arms, wide hands, long knobby fingers, and scuba fins for feet.

My toes were bulbous monstrosities hidden inside of size 11 wrestling shoes bulging like a stuffed boudin sausage skin. My blue Belaire singlet was pulled taunt by my long torso. I had negligible underarm hair, and my pale face and shoulders were dotted with bright red pimples that stood out against the blue singlet. I had auburn hair that seemed to turn red with the increased sunlight of spring, and I kept it cut like a mullet, stopping just before my collar so I was still within state wrestling rules.

My voice had already changed, so at least I didn’t squeak when I talked, but my body was slow to catch up. I had never shaved and didn’t need to. The hair on my arms and legs was soft like the fur on a puppy. I never stripped naked to weigh in because I was embarrassed to have only a few scraggly black hairs hidden by my underwear.

My Achilles Heel, the weakness I couldn’t seem to overcome, was my lack of upper body strength when standing. I was vulnerable to throws and bear hugs by stronger opponents like Hillary. My saving grace was that I had quads thick with muscle from hiking the Ozark Mountains with my dad most summers in the early and mid ’80’s, carrying hefty backpacks full of horse and chicken manure to his marijuana fields hidden far from roads, and I used my leg strength to shoot quickly in the first moments of a match, and I used my physical conditioning to cling to leads while an opponent fatigued themselves trying to score. When they shot on me, my lanky legs sprawled up and pushed their heads down with the added force of long levers giving me an advantage; I owed my meager winning record more to physics and guidance from Coach than strength and talent.

I was taller than Coach but shorter than Jeremy. I stood beside them with my blue hoodie lowered so I could see more clearly, and watched Hillary lead the Lions onto the faded LSU mats to warm up.

The Lions remained eerily silent as they trotted across the wooden gym floor in single file, like a disciplined military unit efficiently moving a double-time. The small windowless gym echoed with every stomp of their feet, but softened once they trotted onto the faded LSU mats. They jogged in a circle and stomped extra hard on every fourth step to create an intentional rhythm that reverberated in rhythm popular with musicians like George Clinton and James Brown, who said funk is alwys on the one of a four beat: ONE two three four, ONE two three four… The echos reverberated in the small enclosed room and we could feel the beat in our chests while we waited our turn to warm up.

I called people in the bleachers spectators, but at Capital they were participants. They stomped in unison with the Lions, and their ramshackle bleachers shook and rattled on every one-beat; loose screws would squeak, and flakes of paint would fall from the bleachers and land on the gym floor.

Every team had its own warm-up ritual, but what stood out about Capital – besides the obvious racial difference – was the contrast of their vocal silence against the musical echo of their feet echoing in the gym. When they finally stopped circling and sprawled into a tight circle, they landed with their faces close together on a silent cue none of us heard. The spectators calmed down and gave the team a moment of silence, and Hillary spoke so softly that I never heard what he told his team as they prepared for battle. For about two minutes, the den became a church; there’d be no stomping or squeaks from the stands, just an occasional cough or someone clearing their throat.

When it was Belaire’s turn, we pulled up our blue hoodies and trotted onto the mat silently and without being synced. It was the first time in our history we filled an entire squad, and no one had thought about a routine or ritual yet. Jermey led, I was second, and 13 Bengals followed in whatever order worked out that day.

We split into two groups like a flock of birds following two leaders, and each group split again into small teams that each warmed up uniquely. We naturally fell into zones of proximal development, small groups of three to five wrestlers who could all learn something from each other, and that zone would change every week as everyone evolved. Our warm-up routine was like a flowing stream that was never the same when you saw it again.

(The zone of proximal development is a concept that came from the Soviet Union after WWII, when 30 Million Russians died and left millions of orphans to fend for themselves in massive gymnasiums without much supervision; toddlers naturally formed small groups, developing their own languages and patterns and mixing in and out of other groups to where give-and-take was balanced. Coach had a master’s in education theory and, because of his role to compete against the Soviet national wrestling team in 1960, at the height of the cold war and while then Senator John F. Kennedy was building his presidential bid, was knowledgable about all things Russian; he had mentioned the zone of proximal development offhandedly, and though Jeremy and I didn’t understand how the Bengals flowed into groups we never questioned it. Even Jeremy and I would weave in and out of being in each other’s groups each week, naturally flowing into zones where we could both learn and teach within the same group. For the next 20 years of Coach’s tenure as Belaire’s coach, the Bengals never developed a routine, unless you consider the Zone of Proximal Development a flexible routine.)

Each group methodically drilled single leg shots, doubles, stand ups, and sprawls, the building blocks of any great wrestler. Different zones practiced these moves with increasing levels of speed and intensity, but all with the intention of waking up muscles after a long day of sitting in classes. After warming up, the team gathered beside Coach in Belaire’s corner of Capital’s mat, and everyone in the Lion’s Den watched as Jeremy and I stepped onto the mat to meet Hillary in the center.

Belaire was the only team in Louisiana with co-captains. Hillary cocked his head and stared at both of us with stoic indifference, more like he processing new information rather than wasting energy pondering why there was two of us. The referee spoke softly to us and reminded us to wrestle fairly. Jeremy and Hillary slapped hands in a modified handshake to show the spectators we would take the message back to our teams. We returned to our corners and matches began at 103 pounds and proceeded up each weight class. Jeremy sat beside Coach and I stood by the team, because rules restricted the number of people on the mat corner to two.

I began warming up when the 129 pounders shook hands, because you never know how quickly matches can end and there was only the 135 and 140 pound match before mine. Hillary did, too, and coincidentally we warmed up almost identically.

Hillary kept his hoodie on and slipped headphones into its shadows. I put on my Walkman headset and pushed play. I don’t recall which song started, but it was probably either Lunatic Fringe by Red Ryder, from the soundtrack to 1985’s wrestling film, Vision Quest, the one where Mathew Modine played a high school senior cutting unhealthy amounts of weight to take on Shoot, the undefeated Washington state champion; or Metal Health by Quiet Riot, which is what I used to start a session lifting weights and always got my heart pumping and my head focused, if only by conditioned response like Pavlov’s dogs. I don’t know what Hillary listed to, but for some reason I believe that his headphones were silent, serving more as a social que for people leave him alone so he could focus on both his team and his warmup.

We began whipping our arms around our chests and stepping up and down as if we were climbing steps on the state capital or hiking up an Ozark mountain. Then we shook our heads and hands and feet faster, breathing in deeply and exhaling slowly. Hillary did jumping jacks and squat thrusts, I skipped a rope, like Mathew Modine in the opening scenes of Vision Quest. My breath was calm, my heartbeat only slightly elevated. A thin sheen of sweat formed on my arms and legs, and behind the scenes my body began pulling energy from meager stores of fat instead of muscle glycogen.

Jeremy pinned his opponent, which triggered Hillary and me to move towards the mat. He took off his sweatshirt and donned his light brown hockey mask, like the one worn by Jason in the 1980’s Friday the 13th slasher films. It wasn’t an actual hockey mask, it was a wrestling mask for kids who competed with a broken nose. A hockey mask is rigid and covered in holes, but a wrestling mask is padded to be soft on the outside and has only two holes for eyes and one for the mouth, but it looked so much like a hockey mask that we all called it one. It was just like the one worn by Jason in the slasher film franchise Friday the 13th; I was the only one to smile about that irony, because so many people called me by my nickname, Magik, that no one considered me Jason any more. Only two other wrestlers in the state used a face mask. Hillary’s nose wasn’t broken like theirs was, but the mask protected him from cross-faces and, I suspect, added to his reputation as a silent killer on the mat; I may have been intimidated had I not been chuckling about the irony of wresting Jason.

I donned the state mandated headgear and took a few minutes to adjust the straps so they’d press tightly over my ears and protect them against cauliflower ear, that wrestling disease that comes from tight headlocks that destroys cartilage. I barely understood the ref when he called us, but I knew the routine and what to expect. I trotted over and stood in the center and leaned forward to face Hillary. The whites around his dark brown eyes were barely visible in the shadows of his face mask. We slapped our right hands as a modified handshake to acknowledge we were ready.

The referee blew his whistle and I instantly shot a low single. Hillary sprawled, cross-faced the hell out of me, spun behind, drove my face into the mat, threw in a half-nelson, and turned me to my back before I realized how much it hurt. I could feel blood gathering in my nostrils, then I felt my shoulders touch the mat. The referee slapped the mat beside my face.

Hillary pinned me in 22 seconds; it had taken me longer to adjust my headgear before the match.

We stood back up in the center, and the referee held Hillary’s hand up in the air. The applause from Capital’s bleachers was deafening, even with my padded headgear. I could feel the reverberations in my chest as they stomped their feet and hollered. Hillary seemed unfazed, as if the outcome were inevitable and he merely had to go through the motions before having his hand raised. It was almost a compliment that he took time to warm up for our match. One of the things I’d learn to respect about Hillary was that he treated each and every thing he did as if it were the most important moment of his life.

I returned to our corner. Coach grasped my right hand in his and squeezed my left tricep in a vice-like grip with his left hand, looked up into my eyes, and sincerely said, “Good job, Magik,” just like he had 87 times in the past year and a half. I accepted the hand towel Jeremy handed me to wipe off sweat out of habit; I had more sweat from warming up than wrestling.

Hillary strolled walked back to Capital’s corner and began prepping their 152 pounder for battle against Miasha, a junior and second year wrestler who never cut weight because he preferred to have fun with everything he did, and he cheerfully placed in the top four or five of most tournaments with a full belly from lunch; he hopped off the bleachers and removed his hoodie and jogged onto the mat without warming up.

Coach and Jeremy sat on the corner of the mat, and I sat immediately behind them in first row bleachers, separated from the mat by about ten feet of wooden floor. Rules only allowed two people on the corner of the mat. From my perch behind them, I watched Miasha wrestle with as much focus as I could muster, but I was distracted by being lad to have the hand towel. I used it to dab the drops of blood I felt building in my nostrils, a result of Hillary’s brutal crossface. To feel what it was like, rotate your head to one side and try to hold it there with all of your strength, and have someone push a baseball bat covered in abrasive Brillo pads across the bridge of your nose and force you to look the other way.

Capital’s 152 pounder pinned him towards the end of the first round. My nose had stopped bleeding by then. I kept the towel in my hands so no one would notice the red blots.

After Capital’s heavyweight pinned Big D, both teams lined up and walked beside each other, slapping hands to congratulate each other and completing the circle from when team-captains shook an hour and a half before. I don’t recall the overall team score, but Capital won about 70% of the matches. Still, it was a victory. Coach reminded us that this was the first time in Belaire’s history that we had a full squad, and that momentum carries teams forward.

It was November, so days were short and we rode back to Belaire illuminated by street lights and traffic signals along Florida Boulevard. Despite it being fall weather in most of America, the deep south was still warm, a reason that Dallas was chosen to kill Kennedy as he rode through town in an open convertible, a subtlety of planning lost on people from colder climates. All of our windows were cracked open to allow air flow and flush away the stench of our sweaty post-match uniforms. Everyone joked with each other and talked about what they’d do differently next time.

The Bengals were chatty on the rides back, and even Jeremy would loosen up and joke around about how each person did. We talked about what happened on the mat and how we could improve; Miasha said he missed my match because he blinked.

I don’t know why Belaire evolved to chat about our matches on rides home, but I believe that immediate constructive review helped us improve. A famous Harvard research study years later would compare learning from three groups of people, one that only reviewed material immediately after a class, one that only reviewed before an exam a week later, and one that reviewed somewhere between; unequivocally, immediate review improved performance.

A bit more than year after that match, when I’d be a paratrooper in the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment during Desert Storm, our teams would do the same thing after every battle. We called it an After Action Review, an essential part of small team growth used by practically every combat force in the world, especially small teams who learn from each other like the Bengals learned through zones of proximal development. I would use a form of an after action review professionally for the rest of my life, and I’d use that Harvard study to accelerate through my college courses after the army, and I always looked back at the ride back from Capital as the first time I thought deeply about how to use what I experienced today to improve my performance tomorrow.

I had a lot of time for internal reflection. My nose was sore and I was staring at the blood-stained hand towel. I ran my tongue across my front teeth, which had had braces until only three months before, and I thought that at least I didn’t have to wear a mouth guard any more; that was one thing for which I could be grateful.

I held the towel in my left hand and made a tight but relaxed fist with my right hand with the thumb pointed up. I pushed it down across my left forearm and felt the rigid force push the left hand and its towel down. I rotated my thumb sideways and pushed again, but my right wrist deflected instead. That was one of the first lessons I learned from Coach, using biomechanics to add strength to my half-nelson; the effect is so pronounced that you could try it now and instantly see the benefit. I still do it to this day, a talisman I carry with me at all times to remind me of the meaning behind the overused cliche to work smarter, not harder.

I performed my own after-action review inside my head. I had shot well, and didn’t see anything to improve my shot or setup. I needed to be stronger. And faster. I sat with my face rotated away from Big D and squished against the side window, watching lights from strip malls and po-boy shops fly by. I thought to myself: I’ll set my alarm 20 minutes earlier for tomorrow morning’s workout before I left for school.

Coach turned away from Florida Bulevard by the strip mall filled with bright lights from the Vietnamese business district with hand-written signs illuminated by flood lights and advertised things like: “Bon-Mi, a Vietnamese po-boy.” Baton Rouge had dubbed Little Saigon after Saigon fell in 1975 and refugees fled to the similar weather and seafood-and-agriculture economy of Baton Rouge. Belaire had a hard time filling teaching positions because locals had gradual left to newer subdivisions, and many of our classes were led by a stream of substitutes and Teach for America volunteers. It was by luck that Coach accepted the role as our driver’s education teacher and assistant football coach in 1980.

He turned onto Tams drive and pulled into our gym’s parking empty parking lot, where parents were parked under the lights and waiting to take their children home. Everything and everyone looked different to me, and it wasn’t the lighting. Only three hours had passed since we left, but I was a different person and seeing things from a new perspective. The stream appeared the same, but it wasn’t.

Go to the Table of Contents

- From “Hoffa: The Real Story,” his second autobiography, published a few months before he vanished in 1975 ↩︎