Wrestling Hillary Clinton

“I missed wrestling in the junior olympics because I overslept,” is what I told most friends later that summer. It was true, in a way. I never told Coach what happened, because he didn’t ask; he never asked about anything that happened in the past, only what I was doing today for tomorrow. But when Mrs. Abrams asked if I were okay – she didn’t ask what had happened to my face – I told her all of what had happened that day. I was transparent, like she had taught me to be.

“I passed out and didn’t wake up until late this morning,” I began. I was staring at my big feet. Not from shame, but from exhaustion. It had been a long senior year that had terminated in a long week at the downtown olympic training camp.

“I must have cut too much weight. I was training and passed out from not having drank enough water.” Not drinking water was common for wrestlers the day we weighed in, because every gram of matter mattered when your team relied on you to fill a weight class.

But I wasn’t first-string, and the team wouldn’t miss me, but I had still tried to make weight. What I didn’t tell Mrs. Abrams is that I had run out of money. I used cutting weight as an excuse for why I didn’t eat pizza with her sons, Big Head, Mace, and Erik the Viking. I wasn’t staring at my feet from shame, I was staring at my feet as a consequence of fatigue.

Coach had ended a lot of practices by reminding us what Coach Vince Lambardi always said, that fatigue would make a coward out of anyone. And though I couldn’t change how tired I was, I could try to not be a coward and tell Mrs. Abrams the whole truth, so I told her about that morning, and a lesson I had learned from Coach. But I focused on that day and not what led up to it, except to clarify what would have been unusual.

After I woke up that morning, I had used my last quarter to call her from a pay phone at the convenience store. It seemed like only yesterday I would have only needed a dime. And, back then, no one had cell phones or electronic devices, so if you were in trouble, you could only call numbers you had memorized. Fortunately, Baton Rouge only had one zip code, so, growing up, I only had to remember seven numbers for Big Head, though I hadn’t called his house since phone calls were a dime. But I knew he wouldn’t be home. He was with most of my friends, in Florida for Senior Trip, but Mrs. Abrams would be there. She was still recovering, emotionally, from Mr. Abrams passing away, and her parents, Mr. Jack and Miss Joyce, had returned home to Texas after watching Big Head and me graduate from Belaire High.

I had been training lightly late after our last day of practice, a routine I had developed of tossing around the dummy before mopping the mat and bathing. But on that evening something went wrong, and though I never have remembered passing out, I remember waking up the first time and not knowing what day it was.

I woke up with the side of my face stuck to the mat. I rolled over and felt the skin on my right cheek stretch, and I heard the unmistakable sound of peeling something off of a hot vinyl car seat or wrestling mat. My head hurt, and my vision was blurry.

The first thing I noticed was that I couldn’t even distinguish the asbestos from the ceiling joists.

The second thing I noticed was that my shirt stank.

Then I passed out again.

I woke up again, and crawled across the mat to the water fountain. I drank deeply, and fought back the urge to vomit. I wasn’t thinking, I was moving out of habit, and I moved to the bathroom and was shocked by my reflection in the mirror.

The right side of my face was covered in small, raised rings of red ringworm. I realized I must have been asleep for a while, and I slowly rotated my body to see my back. The backs of my arms were covered in ringworm, too. I pulled up my shirt and saw a few larger rings on my shoulder blades. I moved my eyes as far into their corners as I could and looked at the back of my head. I moved my hair aside and search all around my scar, and was pleasantly surprised to see that it was free from ringworm. That splash of preventive fungicide must have worked; I could celebrate that, at least.

I suddenly felt too dizzy to stand, so I stumbled back to the mat and leaned against the dummy. He didn’t have ringworm, and hadn’t missed any bus trips to the junior olympics, and I told him his day was going better than mine. He didn’t answer.

I alternated between sipping water and talking to the dummy, trying to form a plan that hopefully involved food. After a while, I walked outside and across the street to the convenience store, but I was down to a few half dollars and a quarter, and I had to make a choice, so I called Mrs. Abrams and planned to use my half dollars for gas in my motorcycle.

But no plan comes together if you don’t know the full situation, and my plan fell apart a few minutes later, when I discovered that my motorcycle was missing from its hiding spot in the alley behind downtown’s wresting gym. When I realized it had been stolen, I leaned against the trash can I had been pushing in front of it and simply sighed. It had been a long week.

But at least I still had my half dollars, so I walked back across Government Blvd and used two of them to by a sugary fried pie snack that I devoured in less time than it took me to write this. Then I used my last two halves to buy a cheap hotdog. I had a few dimes left over as change, so after I devoured the hotdog I bought as many cheap candies as possible. The candy jar on the checkout counter, next to the jar of pig jowls and chitlins, was full of 5 cent balls of sugar flavored like New Orleans’ pralines. I swallowed at least five of them before slowing down and enjoying the last few.

One of the beautiful things of youth is being able to eat like that and actually feel better afterwards. I similed as I walked down the sidewalk, towards the River, and a mile later I was standing on the levee by the riverboat casino and the big Red Stick that marked where the French discovered and named Baton Rouge, much to the surprise of the naitive Americans who lived there and had painted a large tree pole bright red to advertise their land. It was a popular spot to relax and watch people board the Baton Rouge riverboat casino permanently docked under the bridge.

Across from the big Red Stick was the Centroplex, where I had wrestled Hillary. I think 2,000 people paid to see the finals, but it held 10,000, and hosted concerts and basketball games and big wrestling tournaments, like the city meet. Hillary pinned me 47 seconds into the second round, but it had been one of the best matches I had ever fought. He was just that good.

He went undefeated in the state tournament two weeks later, and I lost both of my first two matches in surprise victories for the underdogs. I didn’t make excuses, and Coach simply told the coaches who asked that I had been tired from helping take care of my grandmother. He hadn’t known about Mr. Abrams’ funeral and my grandfather about to die – he didn’t have much time to read the newspaper during wrestling season – and I was too busy with team-captain duties to talk about anything other than wrestling.

I stared at the Centroplex, and realized why I wasn’t upset that my motorcycle was gone, or that I was covered in ringworm, or that my stomach had begun to cramp from too much sugar too soon after fasting. It had happened, and now I had a choice. Coach had taught me that. I saw it now. I wasn’t just repeating his words. I saw it.

Coach rarely offered advice, and the only two pieces of advice I remembered was how to have a happy marriage, “No matter what kind of day you have, when you get home, kiss your wife on her cheek, and ask her how her day was,” and how to choose a career, “Hog farming. You can’t go wrong, hog farming.”

And not only did he not offer advice, he never talked about himself. Everything I learned about him was from other coaches.

He had driven me around Louisiana the summer after Uncle Bob died. I had gone to the same wrestling camp then, but missed the 1989 junior olympics because I moved in with Uncle Bob and Auntie Lo to help him for the last few weeks of his life. I don’t know how Coach learned that, but somehow he knew that I could use extra practice, and he asked if I would like to help him deliver gym supplies to New Orleans, and that if I wanted, he’d wait while I practiced with the Catholic schools. It would be good for the team, he said, and I agreed.

I when I saw him at school after Uncle Bob died, just after I was emancipated and joined the army. when I was looking for a gym to use over summer, and he offered to drive me to and from New Orleans the rest of the summer so that I could train with the big Catholic schools that had year-round programs. (That’s probably why they beat Belaire so badly every year).

He’d pick me up by 6am, and drop me back off at Mrs. Abrams’ by 4pm, and wait for me to wrestle for an hour or two at different schools, depending on their schedule. He used the time to drop off big bottles of fungicide and mops at the smaller schools surrounding the big Catholic schools. They were even poorer than Belaire, and he told me he started an athletic supply company so that he could purchase bulk fungicide cheaply and give it to them, but the big Catholic schools paid him a fair price for the supplies, so it wasn’t money out of his pocket. I sensed that he preferred spending time on more important things than exchanging money.

His son was a coach at one of the big Catholic schools, but you wouldn’t have known it. Craig Ketelesen was huge, and an excellent wrestler. He had been Belaire’s only state champion. And they didn’t speak like father and sons I knew. Neither had pulled a knife on the other, that I had seen, and Coach always said Craig’s name correctly. They just seemed happy to know each other, and after my dad went to jail, I gravitated towards any families that seemed happy to know each other.

Craig helped me as if he were my coach, or if I were a part in his family. But he never told me about his father. Instead, I learned about Coach from the coaches on our drive home along the River Road between New Orleans and Baton Rouge.

They’d talk to me while I helped unload equipment, and speak about how much Coach helped them. I barely understood them, because the Cajun French accent is thick down there, but they seemed to talk about a different Coach than I had known for three years. The same characteristics, but a different history.

Coach was a short, stubby man with thick forearms, like Popeye. When I asked how his grip was so strong, he said it was from tossing bails of hay all day on his father’s farm in Iowa, but I could strengthen mine by crumbling newspapers into tight balls, one sheet at a time. He even had the day’s newspaper in his truck, though he rarely had time to read it, so he let me crumble sheets on the drive to and from New Orleans each day.

I never thought more about Iowa until I heard other coaches talking about him, and how he led LSU’s wrestling team to beating the famous Iowa wrestling team. LSU had recruited him from there, where he was assistant coach to the legendary Dan Gable, coach of Iowa and the U.S. Olympic Wrestling Team. And Coach himself had been on the olympic team, and a national champion, and was in the Wrestling Hall of Fame, and had brought Dan Gable to Baton Rouge to coach all high schoolers no matter which school they came from. Everyone seemed to find ways to send their high school wrestlers to LSU’s summer wrestling camp without money exchanging hands.

And, some would say, he was a marine in the Korean war. Others would say he had also played football and baseball for Iowa the year they went to the national series. One coach handed me a copy of USA Wrestling magazine focused on Coach, and told me that he had started Louisiana’s chapter, and that’s what allowed all schools to access wrestler’s health insurance. Insurance cost is what had kept them from providing a safe place for kids to train when school was out for summer, they told me. Coach helped all of Louisiana.

Other coaches told me more, but I couldn’t understand the thick accents near tiny towns like Napoleonville, Thibodaux, St. Martin, and Broussard. And, closer to Baton Rouge, I was surprised that I couldn’t understand what is now called African American coaches; at that time, and unfortunately still in 2020, Baton Rouge was so segregated that schools would be 96%-100% African American, within walking distance of neighborhoods that still had shotgun shacks left over from the civil war, and bullet holes still in their churches from what many people in Baton Rouge called the War of Northern Aggression. Then, as now, schools are funded by local taxes, and the cycle continues, but I never forgot the summer of 1989 when I saw it first-hand and reaccessed my views of privilege. I was lucky to know Coach.

I was noticeably surprised when Coach pulled into Capital High School, near the state capital, and Hillary Clinton’s coach greeted us. I couldn’t understand what he said, but I saw that he extended his hand low enough for Coach to shake it, and Coach clasped it and reached up to the coach’s huge bicep and clasped it firmly. His forearms were almost as thick as the other coach’s bicep, but I was the only one who seemed to notice.

“Good to see you, Coach,” Coach said. It was the same way he greeted every other coach, regardless of their size. It was the same way he greeted me every morning, except he called me Magik. And it was the same way he greeted Mrs. K; though he kissed her on the cheek instead of clasping her bicep. I never saw him actually ask he how her day was, but I knew he cared about everyone’s day the same. That was the Coach I knew.

All that time, I thought he had started Belaire’s wrestling team as part of his job. He was Belaire’s driver’s education teacher and an assistant football coach and an amateur magician, though his hands were too small to back palm a standard poker-sized playing card. But he tried, regardless, more to joke with me than to impress anyone. Most people are afraid to mess up magic tricks in front of people, but Coach didn’t fear failure. That was the Coach I knew.

I read in USA Wrestling that in 1979, probably the year I saw Fleetwood Mac’s Rumors tour, the United States enacted Title IX to provide equitable access to sports for women. But, perhaps people confused equitable with equal, and the law was phrased so that schools had to have equal numbers of women athletes as male athletes, and with teams like football and baseball being exclusively male, and money-generators for schools, the only practical way to comply with Title IX was to eliminate sports that were open to females but dominated by males was to eliminate wrestling, rugby, and several martial arts teams, like judo and karate. Coach went from being an Olympian and building America’s 4th ranked university team to being Belaire High School’s driver’s ed teacher. I don’t know how I got so lucky.

After we unloaded a few bottles of fungicide and a new mop, we hopped back in Coach’s big Ford F150 truck, the one we used to shuttle wrestling mats around for multi-mat tournaments in the winter. It was an unusually cool day for a summer in Baton Rouge, about 90 degrees – or, as Granny would say when she spoke Canadian, “It’s a’boot 32 degrees today” – so we rolled down the windows and drove slowly down the levee, towards LSU, and let the wind blow inside to cool us and remove the stench of fungicide.

“Coach,” I began.

“Yep?” He answered without taking his eyes off the road or his two small hands off the huge F150 steering wheel.

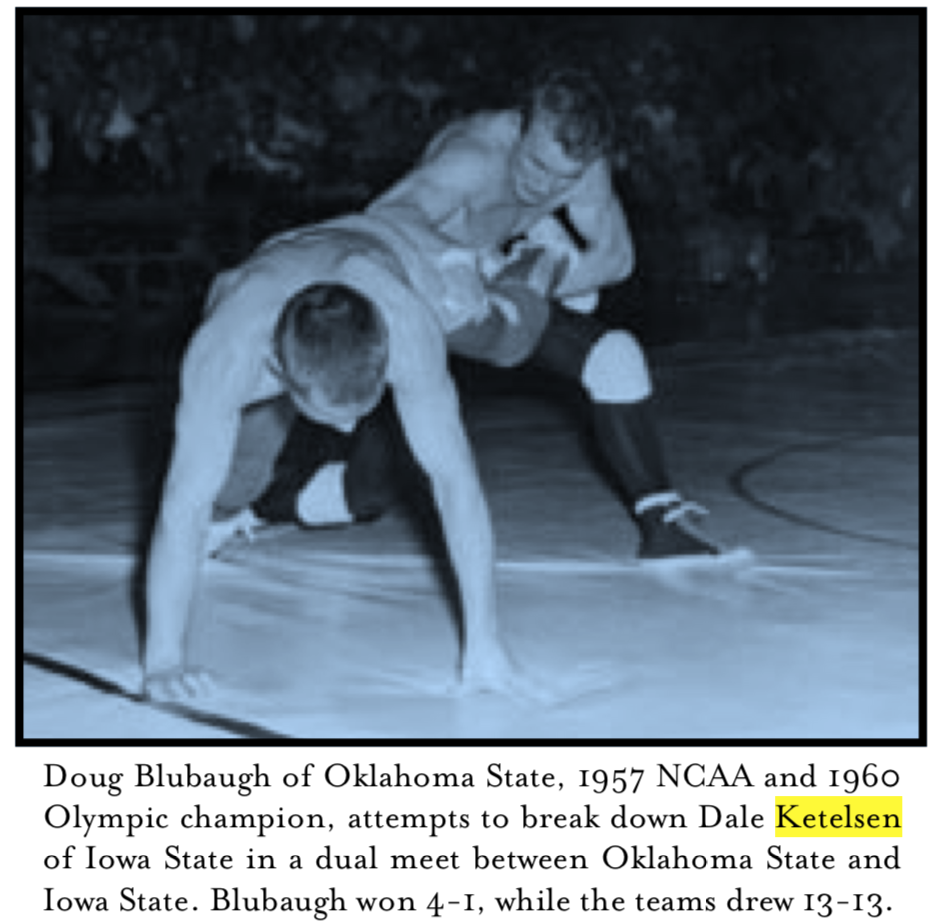

“Why didn’t you compete in the olympics again? All the Coach’s told me you were the second best in the world back then, and only lost because that year because Doug Blubaugh happened to be in your weight class. You could have won the gold in ’64”

Doug won the gold medal in 1960. He pinned every opponent, some of them in record times. He had beat Coach 3-2 in the U.S. trials, and Coach was his alternate for the olympics.

“Well,” Coach began. A few moments passed. He never did anything quickly when he wasn’t on the mat. He took a hand off the steering wheel and held up a stubby finger, but didn’t take his eyes off the road.

“You see,” he said, then paused with that hand in the air, as if measuring the speed of wind that blew fungicide out the window. Even his finger seemed stronger than my forearm. I picked up a sheet of newspaper and slowly crumbled it into a tight ball while Coach answered. This could take a while, I thought. I had no where else to be.

“It’s like this…” He lowered his finger and used both hands to turn the big wheel and steer us onto Government Boulevard.

“After I lost to Doug,” he paused to pull down the turn signal, and looked both ways before turning into the alley behind downtown’s wrestling gym. He turned off the truck, kept his left hand on the steering wheel, and turned towards me to continue.

“… I sat in the locker room and felt sorry for myself for a while.” He paused, and thought about which detail would help me the most. I had never seen him do anything without long-term intentionality.

“Pat came in and sat by my side.” He looked out the window and up at the sky and smiled subtly, like every time he spoke about Mrs. K. “A few minutes later, Doug came in, and he told me something that changed my life.”

Of course he paused after saying that, and got out of the truck to unload fungicide. He gave me his key so I could open the door, and we filled the mop closet with fungicide and a new mop. Back in his truck, he slowly got back onto Government and the interstate, and we rolled up the windows and turned on the air conditioner so I could hear him continue, but not be too hot, because it had warmed up afternoon. It must have been a’boot 35 by then.

“He said, ‘someone has to win next, and it might as well be you.'” He smiled, but didn’t take his eyes off the road or his hands off the wheel. My mind sang an old song my dad had played and sang in his car while rolling joints, and another part of my mind pondered what Coach meant. I had no idea, but I sat quietly and thought about it, because I knew he had reasons for anything he told me. I crumpled a sheet of newspaper with each hand before asking him how that changed his life.

“Well,” he began…

To make a long story short, he explained in ways that related to my matches that every time I won or lost, no matter if I won or lost, there was always a next time for both wrestlers, so both can learn and apply it to the next match. But the 1960 olympics were at the end of an era for Coach, and there would be no more matches. He had been an athlete in high school and college – I knew from he had earned a full scholarship in wrestling, and had been the first in his family to go to college – and did his best in the marines, and did his best on national teams and the olympic trials. With Pat by his side, he knew she was part of the next chapter in his life, and that he’d have no regrets because he had done his best in every match, including when Doug defeated him 3-2, and that the next thing he would focus on would be becoming the best husband and father he could be. When LSU disbanded their team, he helped a few coaches at Catholic schools took until Belaire offered him a job as the driver’s ed teacher, and he began the legal paperwork to create Belaire’s team.

I silently thought about what he said and listened to my dad’s song on my mind’s radio.

Six months later, sitting silently on the banks of the levee, looking at the Baton Rouge Centroplex, contemplating the loss of my motorcycle and missing junior olympics, staring at where Hillary had pinned me 47 seconds into the second round, and I finally saw what Coach meant. In my mind, it wasn’t the exact words he used. That would take too long. Instead, ironically, what I saw that day was what I saw written on the gift I bought for Auntie Lo a few days earlier, “The past can not be changed, but the future is whatever you want it to be.”

I was surprisingly happy sitting on the levee a year after missing the 1989 olympics, covered in ringworm and dizzy from too much sugar. I had two more months until I left for the army, and suddenly viewed the summer differently because I saw the future. The summer wasn’t a loss because I missed the olympics, it was a gift of two months of freedom. In hindsight, that’s all wrestling had been about.

Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to loose, is what Janice Joplin sang in her song that began, “Busted flat in Baton Rouge, waiting for a train,” and as when I rode with Coach I had listened to him as my mind sang every song Janice knew to the rhythm of windshield wipers marking time.

But that day, because I didn’t know Coach’s home phone number, I called Mrs. Abrams. We spoke briefly, and I hitchhiked 14 miles to Belaire High School and jogged 2.2 miles to Mrs. Abrams’ home, and I knocked on her door and waited patiently for the next chapter in my life to begin.