A Part in History: Introduction

But then came the killing shot that was to nail me to the cross.

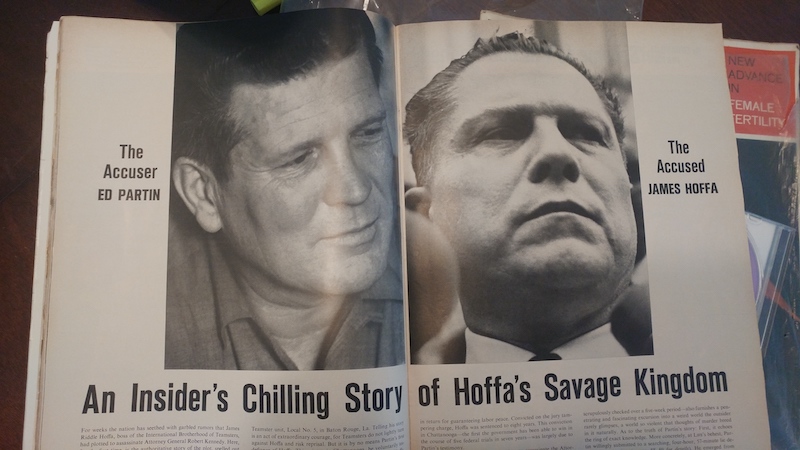

Edward Grady Partin.

And Life magazine once again was Robert Kenedy’s tool. He figured that, at long last, he was going to dust my ass and he wanted to set the public up to see what a great man he was in getting Hoffa.

Life quoted Walter Sheridan, head of the Get-Hoffa Squad, that Partin was virtually the all-American boy even though he had been in jail “because of a minor domestic problem.”

– Jimmy Hoffa in “Hoffa: The Real Story,” 19751

I’m Jason Partin. My father is Edward Grady Partin Junior, and my grandfather was Edward Grady Partin Senior, the Baton Rouge Teamster leader famous for infiltrating Jimmy Hoffa’s inner circle in 1962; his surprise testimony in 1964 sentenced Hoffa to eight years in prison.

Hoffa appealed, but the 1966 U.S. supreme court case, “Hoffa versus The United States,” upheld my grandfather’s testimony. Hoffa was pardoned by President Nixon in 1972 (coincidentally the year I was conceived). Nixon resigned in 1974, and Hoffa vanished in 1975. Hoffa was pronounced dead in 1982, and his disappearance is still one of the FBI’s most famous unsolved cases.

In 1983, Edward Partin Senior was portrayed by Brian Dennehy in the movie Blood Feud. The film’s name was from media in the 1960’s that dubbed the fierce public battles between Jimmy Hoffa and Bobby Kennedy, president John F. Kennedy’s little brother, who had been tasked with one job as United States Attorney General: Get Hoffa. Bobby oversaw FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, and they tasked Walter Sheridan to lead 500 agents in pursuit of what media said was history’s most expensive, fruitless, pursuit of one many by a government: The Blood Feud.

When my grandfather, whom everyone in Baton Rouge called Big Daddy, revealed himself as the mole in Hoffa’s camp, he became an overnight celebrity and was dubbed an all-American hero in Look! and Life magazines for risking his life to stop Hoffa and save Bobby Kennedy’s life against an FBI-alleged plot by Hoffa to kill him. Just like everyone knew what Hoffa looked and sounded like, suddenly everyone knew Big Daddy looked and sounded like.

Brian Dennehy was less famous than my grandfather back then, but he was an up-and-coming star known for his “rugged good looks,” green-blue eyes, and charming smile. Producers felt that Brian could convince viewers that was the Ed Partin described in Hoffa’s second autobiography, published a few months before he vanished: “Edward Grady Partin was a big, rugged guy who could charm a snake off a rock.” That phrase, plus all of the national magazine photos and a few news blurbs where Big Daddy spoke in his drawl, made Brian a good fit.

Blood Feud was a hit, a two-part prime-time series that brought Americans to the screen. Big Daddy, Hoffa, and Bobby Kennedy were the focus. Robert Blake portrayed Hoffa, Ernest Borgnine was Hoover, Walter’s role was reduced to one quick scene, and a daytime soap opera heartthrob portrayed Bobby Kennedy. (Blake he won the academy award for best actor that year because he was so good at what media called “channelling Hoffa’s rage. By then, Brian Dennehy was known as an actor who could reliably portray big, rugged, charming men; his break-out role was as the sheriff who hunted Sylvester Stallone in 1983’s “Rambo: First Blood,” a movie that coincidentally had blood in it’s name, and where Bryan stood up against a well known and intense actor. From his cushy Texas federal penitentiary cell, Big Daddy told me he thought Bryan Dennehy did a fine job portraying him, and that Robert Blake nailed Hoffa. We never discussed Rambo until six years later, when I was a senior in high school and had joined the army’s delayed entry program, which will pop up later in this story.)

Thirty years after Blood Feud, Big Daddy was portrayed by the burly Craig Vincent as “Big Eddie” Partin in Martin Scorsese’s 2019 opus about Hoffa, The Irishman, based on a 2014 memoir by Frank “The Irishman” Sheenan called “I Heard you Paint Houses,” a mafia code for painting walls red with someone’s blood, and that was how Hoffa first addressed Frank, a WWII American infantryman with two years in combat, a mafia hitman with dozens of kills, and, after meeting Hoffa, a local Teamster. (He knew Big Daddy well and speaks of him throughout his book, but I never heard Frank’s name growing up, whereas Hoffa and a lot of the other characters were weekly chatter.) Frank claimed to have killed Hoffa in a Detroit suburban house on behalf of the mafia, though the FBI’s case is still open; “Frank’s “I Heard You Paint Houses” was mostly authored by a professional true-crime writer.

Scorsese raised $270 Million and hired a long list of Hollywood’s most famous actors know for gangster films, like Al Pacino, Robert DeNiro, Joe Pesci, and about a dozen others. Craig was chosen to portray Big Daddy because he had worked with Scorsese before, playing a big, brutal, thug in alongside Pacino and Pesci in the Las Vegas mobster film Casino. But the film version didn’t include the book’s parts about Audie Murphy, an actual all-American hero; he was America’s most decorated war hero, with almost 300 confirmed kills in WWII, namesake of the Audie Murphy Veterans Hospital, and star of more than 40 films including a film version of his own memoir about his two years in WWII, “To Hell and Back.” (Audie’s history was probably why Frank spoke so much and so highly of him in the parts of his memoir attributed to him.) And because The Irishman film centered around Frank, Scorsese defocused the book’s parts about Big Daddy, Audie, and President Nixon negotiating Hoffa’s release from prison; changed Big Daddy’s southern accent to match Craig’s northeastern Italian accent; and called the revised character “Big Eddie” Partin.

The film was a success. It sold out theaters the summer of 2019, and when Covid-19 shuttered the world in 2020, The Irishman was picked up by Netflix and set worldwide streaming records and was available for streaming 24 hours a day. Hundreds of millions of people all over the world got a glimpse at Big Daddy’s small part in history.

In one scene with all the famous actors together, Scorsese lowered the camera angle and placed Big Eddie behind the big names, exaggerating his size and making him loom large over people who didn’t see it that way. I believe that Big Daddy, who died in 1990, just before I graduated high school and left for the army, would have appreciated how he was portrayed in a global film 30 years after his death.

When I spoke with Craig during the pandemic, we chatted for a few hours. To research his role, he had called my uncle, Byron Keith Partin, Big Daddy’s son who looks just like him and was the current president of the Baton Rouge Teamsters, and my great-uncle, Douglas Wesley Partin, Big Daddy’s little brother, who was in a Mississippi veterans home and looked just like Keith when he was younger, and who was also a president of the Baton Rouge Teamsters. But Craig couldn’t get an answer to his question about what were the characteristics of Big Daddy that he could use to portray a man who fooled so many. Everyone simply pointed him to Bryan Dennedy’s version and said that was a pretty good impersonation, but that you had to see him in person to get it. Invariably, everyone kept quoting Jimmy Hoffa’s description, and saying that Doug and Keith looked just like him, but there was something special about Big Daddy. I had said practically the same thing when Craig and I had first spoken.

I thought about Craig’s question almost daily during the first year of the pandemic, and then I called him back.

“Wrestling Hillary Clinton,” I said.

I waited for him to ask; it was an old joke I had used for 30 years, every time I held up my left hand and people asked what happened.

“It’s an old joke,” I said. “A kid named Hillary Clinton broke my left ring finger in my final wrestling match my senior year of high school. It was two weeks before Big Daddy’s funeral, and I showed up with my two middle fingers buddy-taped. It healed askew, and to this day my two middle fingers fork like Dr. Spock’s split-finger salute.”

I paused. Craig didn’t say anything.

“Bill Clinton wasn’t elected until 1992,” I said. “The name’s a funny coincidence I’ve joked about since.”

“But the two events are linked in my mind,” I said. “And how people talked about him and the scene of people at his funeral answers your question.”

That sparked his mind. We talked about how scenes define characters, and he suggested contacting a professional writer he knew, one like the co-author of Frank Sheenan’s memoir. I thanked him, but said I wanted to try writing it myself first.

This is the current version; I keep it on JasonPartin.com

There are dozens of Jason Partins on the internet. When I began writing this memoir, I Googled my name for the first time and saw that a few were criminals, a few were people typical in anyone’s town, and one was an aging mixed martial arts competitor who coincidentally looked like a younger version of me. (I do not look like Big Daddy; I look more like my grandmother and father.) One was – and is – my second cousin, Jason Partin. He’s my grandfather’s nephew and a year younger than I am. That Jason was the football star of the Zachary High School Broncos when we were kids in Louisiana and I was wrestling with the Belaire High Bengals. The last time we saw each other was at Big Daddy’s funeral. He went on to play for Mississippi State University, and he currently owns the largest physical therapy treatment center in Baton Rouge. Today, his smiling face looks down from the Lamar Advertising billboards that line I-110 between downtown Baton Rouge and Zachary.

When I began writing this, I was the smiling Jason Partin dressed in a suit on two university’s web sites (I inherited Big Daddy’s smile, which is more a feature of our cheeks pulling up on the corners of our mouths than a genuine smile). I ran a hands-on innovation laboratory called Donald’s Garage, named after Donald Shiley, a mechanical engineer who co-invented of the world’s most successful heart valve in his home garage. Coincidentally, I had invented medical devices using pyrolytic carbon, the same material Donald used. I was also listed as an advisor to a few programs on using entrepreneurship programs in public schools to facilitate equitable education, with a biased focus on hands-on learning in engineering and physics.

I’m the Jason Partin listed by the United States Patent and Trademark Office as an inventor on several patents as either Jason Partin or Jason Ian Partin. There were a few other Jason Partins listed as inventors on patents for a range of gadgets, but all of my patents are for medical devices, implants, and technologies that help heal bone fractures and repair soft tissues. Most are focused on small bones and joints, like the facet joints spinal vertebra, ankles and toes, and wrists and fingers.

I show up on Linkedin as a university instructor (though I use the word facilitator or coach), a consultant for corporate quality assurance, and as a collaborator on international medical device regulations written by agencies with three-letter names, like the FDA, ISO, etc. I’m a graduate of Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge, with a bachelor’s degree in civil and environmental engineering, and The University of Alabama at Birmingham, with a master’s degree in biomedical engineering. I’m also listed on a few military databases as a veteran of the 82nd Airborne in the first Gulf war of 1990-1991, and as a communications liaison with a multinational peacekeeping force in the Middle East in the early 1990’s. (Judging by recent news, we didn’t succeed; fortunately, there’s still hope.) And, I’m listed on the Louisiana High School Athletic Association’s web site, LHSS.org, as silver medalist in the 1990 Baton Rouge city high school wrestling tournament at 145 pounds, having been pinned by Hillary one minute and forty seconds into the second round.

Hillary would go on to win state, with an undefeated record for 1989-1990.

To this day, every time I look at my left hand I see a lifetime of events leading up to writing this. During the pandemic, I began writing a memoir overlapping wrestling Hillary Clinton with Edward Grady Partin’s small part in history, and that’s part one of the story.

Go to the Table of Contents

- From “Hoffa: The Real Story,” his second autobiography, published a few months before he vanished in 1975 ↩︎