A part in peace

“Bull fuckin’ shit. Get Colonel Don’t-Remember on the mic, Captain.” Said The Sergeant Major Hogard to a British army captain.

I saw the captain’s face look surprised. He captain didn’t know The Sergeant Major, so he didn’t get Colonel Don’t-Remember on the mic. Instead, he kept explaining what he thought I had done.

“And, offending an officer,” he continued, staying calm on his end of the microphone in the Sinai peninsula of Egypt.

Everyone in North Carolina thought about that for at least five seconds, which I felt was a long time, because I was on the floor, in pushup position, hoping they could keep me out of jail in Bum Fart Egypt.

The Sergeant Major finally said something. “Hmph. Well, I could see that.”

“Yeah,” said someone else.

“Um Hum.”

“Sure.”

“Probably had a finger pointed at him.”

“Dagnabit,” Robo Top said.

He had summed it up for all of them. No one said anything else.

I was in BFE, according to a handwriten sign I had stumbled across, with a hand-drawn a map of the Sinai Desert, and a star on it, labeled it “Bum Fart Egypt” with an arrow saying “You are here.” I don’t know who drew it it, but I’m sure we would have gotten along.

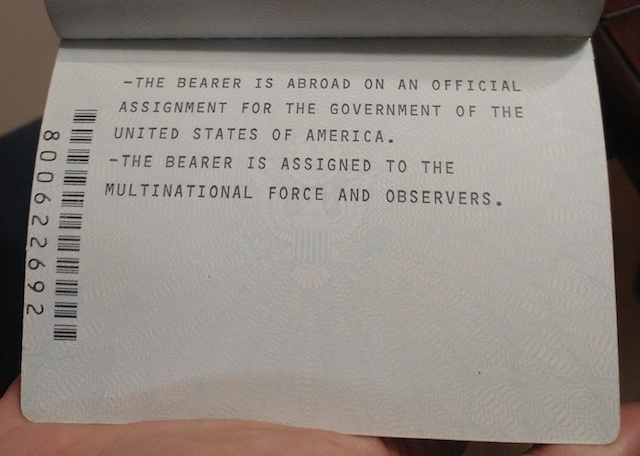

Our base was in the Sinai penninsula of Egypt, in land released by Israel after they took it in one of the Arab wars of the 1970’s. Jimmy Carter had negotiated a truce between Israel and its neighbors, and organized a 17 nation coalition to monitor adherence to the Camp David Peace Treaty. We were midway between Kind David’s kingdom in Israel, and Mount Sinai, Egypt, where the bible says God wrote down the ten commandments, including Thou Shall Not Kill. A lot of decendants from Abraham had been killing their neighbors since then, and we were there to observe and not to interfere.

We had no weapons other than pens. We wrote down what we saw. Most of us would have preferred guns, or at least a sword.

One of the roles of Communications Laisons was to ensure everyone understood their purpose, and knew when situations changed. It was not about rank; it was about having accurate current information, and ensuring diverse people from all over the world understood situation updates, and that senior commanders heard about anything unusual someone may have observed.

We flew by helicopter to visit them in remote outposts, where they rotated guard shifts and observed the blue desert skies and the Red Sea 24 hours a day. They counted the number of cargo ships navigating the sea shared between Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Israel, and they recorded the types of airplanes flying across the Sinai neutral zone. Most of the soldiers we visited were bored. Besides the Israeli wars, not much had happened in the Red Sea since Moses was said to have parted it and walked across. No one had seen anything like that, they reported to me. They were happy to have someone new to tell that joke to.

We wore the same brown desert uniforms and orange berets, not blue helmets like the United Nations. We were unique. We were the Multinational Force and Observers. Each country had different rules, and the United States has been rotating soldiers there every six months since Ronald Reagan was inaugurated in 1981, though someone had engineered it a few years before.

President Carter led the creation of a 17-country peacekeeping force there in 1979, the year Wendy regained custody of me, though I’m sure the two are unrelated. It took them a few years to work out the details, and to build a base in the Sinai desert wilderness. There’s no water in the Sinai, which is why the Egyptians banned people to there. With the exception of the scuba resort near our base, no one stayed in the Sinai peninsula.

It was full of mines that killed people. Countries been leaving explosive mines in the desert and sea of Sinai ever since Britain rearranged their borders after WWII. Mines don’t have minds, and they don’t turn off when forgotten about. They linger around for decades, and one of the MFO’s side hustles was scuba diving to recover them. I felt that work was useful.

I was excited when I landed in Egypt a week before. I was wearing a new, brown desert camo uniform, and didn’t have to get badges sewn on it. My commanders in the 82nd strongly encouraged me to wear my badges on my old, green jungle uniforms, when I was at Ft. Bragg. They couldn’t make me do it. No one could make me do anything; I was just like my dad. But I was the most highly decorated enlisted man in the 82nd Airborne, a Full Bird Lieutenant Colonel commander told me. He was commander of the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment. I should wear all of my awards, he said. I’m the only one of his paratroopers who chooses not to, he pointed out.

His commander had strongly suggested that he talk to me about that, I suspected. His boss was a Three Star General who commanded 14,000 paratroopers in the 82nd Airborne Division. Most people did what he asked. He looked just like a famous muppet, I remembered.

The award in question was my Combat Infantry Badge, a patch on your uniform about the length of your finger. It’s a civil war era rifle, and surrounded by a wreath. It signifies that the person in that uniform was an infantryman, and had fought in combat. Walking while wearing it implied that you won. It carried more points for ranking a soldier’s potential in 82nd Airborne planning spreadsheets, and in batallion commander performance evaluations, but soldiers who had been given it weren’t required to wear it.

Regulations said that each soldier could choose whether or not to showcase awards that were earned or given; only the unit affiliations were required. And the Uniform Code of Military Justice, section 17, row 4, second sentence, implied that I could not be made to adorn my uniform; there were religious connotations, and I could even claim to be a conscientious objector if I wanted.

The full bird listened to my reasoning. I was proud of my Expert Infantry Badge. I had earned it through intention and effort and iterations; only three of us out of hundreds who tried received it that year. But I had been given the Combat Badge. I was there, in combat, and I was lucky to have lived, but I didn’t do anything special. I just listened to some good leaders, I said truthfully and respectfully. I choose to become an expert, I said sincerely and repectfully when he asked me to explain myself. I feel gratitude for what was given, and appreciate what I earn, I said. He smiled as he listened.

After I responding to his probing, he leaned forward from his reclined chair and slipped his feet back into his flip-flops. He was in a t-shirt from a concert tour in the 1970’s. It was one of the bands my dad liked, but I can’t remember which one. It was Saturday, because his boss had asked him to make sure my uniform accurately represented our deployment status before Monday.

The Full Bird was in shorts, because it was his office. I was in a pressed jungle camo uniform, because Captain Holly asked me to when the Full Bird called him at home to get me.

My jungle uniforms had badges for airborne, air assault, combat with the 82nd, and Expert Infantry. And my name, rank, country, and unit, of course. He wanted me to swap the expert badge for the combat badge, which most people in Ft. Bragg bragged about.

He sighed, but he was smiling, and the sigh sounded almost like a chuckle. He leaned forward and looked me in the eyes. He said, in a calm and kind voice, “You’re right, as usual. But I can choose who spends every weekend cleaning latrines. You have two years left in the army, right?” He smiled. He was right, as usual.

By Monday, all of my uniforms had my Combat Infantry Badge. Friends helped me find a tailor open on Sundays in the War Zone next to base, and they kept laughing and slapping me and telling me “I told you so!”

I had been happy to receive new desert camo uniforms with my new unit patch, an orange dove with an olive branch. They didn’t require any country-specific badges. I arrived in BFE knowing only four people, and we were dispersed throughout the Sinai, and we rotated our schedules so that we rarely saw each other. And we had only been there a week, so we didn’t know how things worked there yet, so we weren’t pushing our boundaries yet.

No one knew what to do with us, because we were “Communications Liaisons,” something they had never heard of. All they knew is that a general had requested that we join them. They were annoyed. All they knew about me was my name and rank, and that I was from the 82nd.

A Captain misidentified me the first week. He confused me with someone named Parker. He left for two weeks after telling a first sergeant who wore a wrinkled uniform and smelled like cigarette smoke to make an example out of me. That first sergeant obeyed, and when he first spoke to me, he told me that I couldn’t come her from the 82nd Fucking Airborne and act like a delinquent under his motherfucking command. It took me a two days of doing pushups and listening to him to learn what he thought had happened.

Someone had woken up that captain late one night a week before, drunk, banging on the door of his one-room trailer with one window. He peeked out, and even though he didn’t have his glasses on he could see one of the new paratroopers kicking his door. The paratrooper couldn’t see him, because it was dark inside the trailer, and the window was a mirror to anyone in the moonlight.

He probably sighed; the 82nd had a reputation of being heavy drinkers, and a few hundred had shown up last week. He was expecting trouble. He didn’t need his glasses; he saw everything already. He leaned against his window to read the soldier’s name tag, which brought him into the paratrooper’s view.

“Come out and fight like a man!” he yelled as he gave the window a few quick slaps. The captain, who had graduated from West Point in political science, and had never seen combat, didn’t open the door.

That guy looked like me. He was a white guy with a shaved head, and he was wearing a desert camo uniform without any badges. His name tag said Parker, and he had on the same 82nd Airborne “AA” patch, for All Americans, though the joke among other MFO countries was that it meant “Alcoholics Anonymous.”

Parker stood next to me in line at breakfast the next morning because we had lined up alphabetically to complete some paperwork. He reeked of booze. There were seven bars on base, and most of the new arrivals from Fort Bragg had been partying. There wereathe surprising number of women on base, because of the Danish and Italian military that were also a part of the MFO. The Devils in Baggy Pants were in heaven, and the locals wanted to set an example about what was not acceptable. The Captain pointed towards me.

“Partin, Sir?” the First Seargent asked. I couldn’t hear them, but I wondered why a captain was pointing towards me, and wondered what the new first seargent had said. He didn’t look happy. But he never had, so I didn’t think much of it as I waited in line for breakfast. I was tired. It had been a late night. There was a 24 hour gym, and a few friends and I worked out because we had nothing else to do. We didn’t drink, like the rest of the Devils.

“Yeah, that sounds right,” I heard the captain with glasses say. ” Make an example of him for the other soldiers; they all reek of alcohol.” I agreed. Parker reeked of booze, though I called him the same nickname everyone who knew him well did, Chuck. We had no idea why, just as I never understood how he could get squared away so quickly every morning. He smelled like booze, but he looked fine. Even I looked tired, and I never drank.

Chuck and I had been on a lot of missions together since Desert Storm. We considered each other as close as the closest of brothers; not Cain and Able, but brothers who are there for each other if necessary. You’d want him on your side in battle. He got a little rough when he drank, though. Once, he stabbed me in the back three times after he had a few beers. A few of us were fighting, like friends do, and I was winning, like usual. Chuck hated losing, so he grabbed a dive knife off the floor of the boat and started pounding me with it. He acted just like his favorite t-shirt with a cartoon of a frog in a stork’s beak, stopping itself from being swallowed by choking the stork’s neck with all of the strength; his shirt said, “Never Give Up!”

Chuck never gave up. He kept hitting me with a dive knife as I tightened my choke hold, and after a few minutes the knife blade pierced its protective sheath. He stabbed me in the back twice before he heard me shouting to stop, then he stabbed me once more.

“That’s it, asshole!” I said, and choked him out with more effort.

I wasn’t bleeding too badly. it would have been worse if I hadn’t been wearing a 5mm thick dive suit. He gasped for breath, and laid against the boat rail, then he laughed and threw a pack of C4 explosives at me. Of course, we stored the detonation caps separately, per army regulations.

Now he was standing in front of me, in alphabetical order, waiting for pancakes, and reeking of booze. He had no idea where he ended up after last call at the Danish bar, some time around 0200 hours.

“Yes, Sir. I’ll get that squared away, Sir,” was the last thing I heard the first sergeant say before the captain left for two weeks.

He called me into to his office. He and yelled and ordered me to drop to the ground and start doing pushups. I was shocked, but responded and tried to understand the situation. At first, all I learned was that he didn’t like arrogant Airborne assholes who thought they knew everything about the motherfucking army just because their white ass jumped out of an airplane. I couldn’t see him because my face was towards the floor as I did push ups, but I listened to every word.

“You think you’re a big, bad mutherfucker, do you? Push! Push!” He reeked of cigarette smoke. I doubted he had done a pushup in years.

For the next week, he yelled at me and ordered me to do pushups whenever he had nothing better to do; which was often, I thought to myself. I never saw him do one.

I was in BFE, but on a multinational military base with complex regulations. The Uniform Code of Military Justice was a guideline, but there weren’t clear rules here, and no one understood how everything was supposed to blend in together with so many different ways of doing things. People made a lot of assumptions, and there wasn’t any way to know who was right and who was wrong, so most people blindly followed orders. I did a lot of pushups that week, but kept my mouth shut, unless asked to speak.

I bit my tongue, figuratively, and focused on my breathing, literally. I kept silent, except when I answered a question with “Yes, first seargent,” or “No, first seargent.” I questioned every choice in my life that led up to that week. No matter what happened, I knew I would not re-enlist, no matter how much I enjoyed my team back in Ft. Bragg. I was even scheduled for the Special Forces selection phase, but not even that could entice me as I simmered under house arrest.

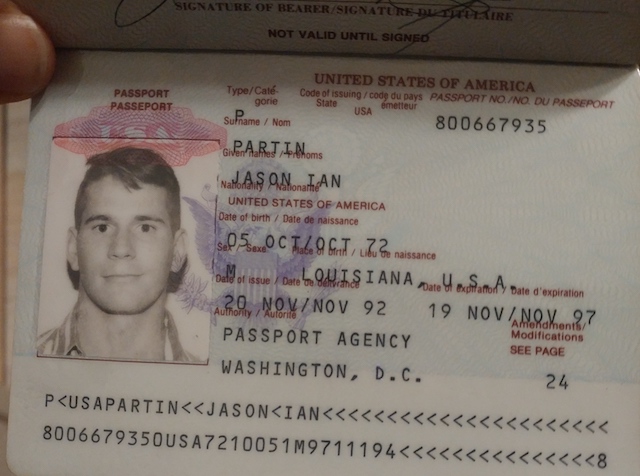

I would leave the army in almost exactly one year, I knew. I had arrived in BFE in January 1993, and my army contract would end exactly one year later. I could do pushups and keep my mouth shut for entire year, I imagined. I wondered what I’d do when I got out. I had no idea. I had thought I was going to accept my promotion, then complete Special Forces selection and then reinlist. A few hundred pushups a day while smelling cigarette smoke was enough to extinguish that plan. Whatever it I would do in a year, I was sure I’d never want to do pushups again.

I did pushups for him every day for a week until we could coordinate a phone call with my former platoon in North Carolina. We used a radio that communicated to a sattelite, which converted our radio to a phone signal in North Carolina. This was new technology then, and not everyone knew what they were doing. In more irony than could be imagined, I was the Communications Liaison that they didn’t know what to do with.

The British Captain responsible for the radio had contacted the Delta Dawg company commander, Captain Christopher Holly, who had assembled a team to speak on my behalf. They agreed that I could very have offended an officer, especially if he had pointed his finger at me, but said there was no chance I had been drinking, so there must be a mistake. They would fly to BFE to understand the situation if necessary, they said.

A few minutes later, a Full Bird Colonel joined the call, and told the Captain to get Colonel Don’t-Remember on the radio – right now, he added. The captain complied, and I was released about twenty minutes later. But I wasn’t free. They stopped making me do pushups and calling me an asshole, but I couldn’t leave until the captain with glasses returned and met me in person.

I knew the Full Bird Colonel well, though. A few months before, he saw me almost offend his boss, the 82nd Airborne commander, a Three Star General.

I was waiting for the Colonel at Division Headquarters. Before he finished his meeting, he overheard me laughing with a few of the soldiers I knew at HQ. I had a framed photograph in my hands that I had found in the War Zone, a rough part of North Carolina where off-duty soldiers go. They had a flea market, where civilians and retired soldiers sold nostalgia to kids stationed away from home, near the War Zone. I was holding it next to the Three Star General’s photograph, and everyone was laughing, because it was obviously funny.

The photo was of a puppet named Waldorf, one of the Muppets. He was the old man you sat upstairs and made jokes about Kermit the Frog’s show. Most soldiers in 1992 would have grown up with the Muppets on television, and as soon as anyone saw the photo of Waldorf next to a photo of General Shelton they realized the joke and started laughing. It’s true. You can look up General Shelton and Waldorf’s. They could be twins. The General became the U.S. Chief of Staff under President Bush, but I don’t know what happened to Waldorf.

I bought the photo and brought it to show because a picture’s worth a thousand words. They were all rolling against the walls laughing, but in a way that was friendly. No one would laugh at General Shelton – he was a respected leader. He had served two tours in Vietnam as one of America’s first Special Forces commanders, and now he oversaw 14,000 paratroopers and a small army of tanks and planes. I was holding the Muppet next to his when walked up behind us laughing.

He was ridiculously tall. His photograph hadn’t conveyed that he was that big. I snapped to attention, like everyone else in the room. He’s from North Carolina, an engineer, and a nice and forgiving human being. He may have not even noticed that I was wearing my Expert Badge instead of my Combat Badge, but I know that soon after that day, my commander gave me a choice of wearing the Combat Badge I had been given, or earning two years of scrubbing latrines on weekends. Now, he was trying to keep me out of jail in Egypt.

I was freed a week later. The captain who wasn’t wearing his glasses when he read Parker’s name tag returned another week later, on schedule, and laughed when he heard my voice. “That’s not him,” he told the first sergeant who had been making me do pushups, who still wore a rumpled uniform, and still smelled like cigarette smoke. The captain asked Chuck to say something, and they realized their mistake.

The First Sergeant in a crumpled uniform that smelled of cigarette smoke laughed, too, and was friendly with me for the next six months. He never apologized to me, and I never saw him do a pushup. But he was a nice guy, after you got to know him.

Chuck wasn’t in trouble; the lesson had been shared with everyone by then, the newness of the bars was wearing off for the new rotation of Americans. And no one wanted to do more paperwork.

A few days later, I heard magic words. The first sergeant told me I had unrestricted freedom for the next six months. I reported to him, on paper, but his instructions were clear: I was free to choose what I did. I had a diplomatic passport, freedom to cross borders in the Middle East without restriction, and broad guidelines to be a Communication Liaison. As long as I didn’t offend anyone, I could do no wrong.

“Excuse me, first sergeant? I don’t understand,” I said in response. He clarified, and I smiled broadly as I began to see the future.

I was able to do as I chose, but not necessarily what I felt like. There were boundaries, but boundaries are like rules; once you understand them, you can have a lot of fun within them. It was like Big Daddy being given freedom to do as he pleased, as long as he remained in Louisiana. Once you understood the rules, you could have fun. Money was no object – I was even getting paid extra $110 a month in hazardous duty pay – and for practical purposes, six months to a 20 year old is a lifetime of opportunity. Time didn’t matter, either. I felt abundant. I was in heaven. I can see why Big Daddy became addicted to respecting boundaries in order to have freedom; that feeling fills a lot of empty space.

I could write a book about the next six months, but for this story I only need to mention Professor Borris Rubinsky. I met him near the end of my second stay in the Middle East – the first had been the Gulf War. We were on a crowded public bus in Israel and I stood up so that his 13 year old daughter could use my seat during the four hour ride beteen Eilat on the Egyptian border and Jerusalem in the heart of Israel. Borris and I had lots of time to talk.

We talked about a lot of things, and I learned that he was called a “Professor Emeritus” at the University of California in Berkley, which I knew was ground-zero for the Hippies that my parents talked about. He talked about his work, and his teams. He ran a research lab, where students designed tiny robots. They were so tiny that they could be injected into your blood and float around your cells, just like in science fiction books. They had sensors that knew the difference between healthy cells and cancer cell, and could choose which cells to destroy. They were like Special Forces teams that healed people. I leaned forward, and listened closely.

He studied frogs. Like Kermit, I joked. I told him how the Cajuns where I’m from make a spicy tomato sauce called frog legs sauce piquante that I loved. He said he studied unique frogs that lived below 0 degrees in salt water near the Arctic Circle. His students traveled there to study them. If we learned why they don’t freeze, we could save human lives. We could freeze cancer cells that were invading healthy cells, and let the healthy cells live even though they would be below freezing temperature. We could learn from Kermit, he said. It ain’t easy being green, I said. I thought about my green jungle uniform back in North Carolina.

I realized we could have saved Uncle Bob, at least for a while longer. Even with more time, he would have only delayed the inevitable, and he still wouldn’t be able to take anything with him. But I thought I’d liked to talk with him now, as an adult, like how I was speaking with Borris.

We passed the Dead Sea, and I noticed that it had continued to evaporate since the last time I was there. It had only been a month or two, but the difference was remarkable. A few weeks later, Israel announced that the Dead Sea was officially two bodies of water after thousands of years as one. They began planning an irrigation channel from the Mediterannean Sea to replinish it, the Med-Dead channel. I appreciated the name; I was always a fan of puns.

Israel had been siphoning water from the waters that had fed the Dead Sea naturally. These waters orginated near the Sea of Galalie, where John the Baptist baptized a 31 year old rabai named Jesus. People said Jesus fed thousands from those waters, and now it was being siphoned off to grow vegetables for hundreds of thousands of Russian Jews who had become neighbors inside of Israel.

Ronald Reagan had seen part of the future – they did tear down the wall in Berlin Germany, and the Soviet Union did collapse. We out spent them on Star Wars, and other things, though we didn’t waste money on vegetables for kids.

When the Soviet Union collapsed, 240,000 uneducated and unskilled Jewish men, women, and children fled Russia because they were finally able to leave after WWII. Israel accepts all Jewish immigrants, and when I was there in 1993 they were overwhelmed by a surge in unskilled workers; they only had a few million people, so everyone felt the impact of having to feed people who couldn’t contribute back yet. They spoke a different language, and didn’t know how to survive in the desert. They had become neighbors, and Israel was trying their best. They had shut off the border between Israel and Palestine, because they didn’t want unskilled jobs going to Arabs when they could be going to Russian Jews. Tensions flared, and fighting could erupt at any minute, not unlike the previous 2,000 years.

A few Israeli soldiers rested their Uzi machine guns on their laps and glanced at us, wondering what a big American was doing talking to a Jew on a civilian bus. I wasn’t in uniform, but with my haircut and how I stood it was obvious that I was in some type of military.

Borris said I’d make a good engineer. I knew Mike was an engineer, but I didn’t understand what he had done before he owned a video arcade and I played Pac Man with him. I knew that Jimmy Carter and General Shelton were engineers, but I don’t know what they did before they were President of the United States and Commander of the 82nd. Borris seemed like a nice guy, and he was on sabbatical, getting paid to do whatever he wanted for six months, just like I was. I decided to become an engineer, and I began investigating how to do that as quickly and efficiently as possible.

I had less than eight months to discover what I’d do. My last day in the army would be January 14th, 1994, the weekend that America honored Martin Luther King on his birthday. I was prepared for college, but I didn’t know what I wanted to do.

I was prepared because I had learned about delayed gratification and compounding interest from Uncle Bob and Granny. When I was 16 years old and joining the army’s delayed entry program, I ensured that my contract included the army college fund. It cost $100 per month, leaving me $600 per month before taxes, which was still a fortune to a poor kid from Baton Rouge.

I had also asked for $100 per month to automatically invest in Series EE savings bonds; they compound quarterly, and you could earn 27%, in a way, by not paying taxes on your profits, if you used the money to pay for an education, which wasn’t bad for a kid who had failed Algebra in high school, twice.

For the last few months in the MFO, I received college entrance and studied for placement exams. The only people I knew who had been in college were officers, and they helped me study.

The British communications captain was a great guy, after you got to know him. He frequented the makeshift British pub soldiers had built, and where Chuck had gotten drunk when we first arrived. He even hosted a party on July 4th, and invited some of us to celebrate the American Rebellion with the Brits.

We laughed and grilled hot dogs with him and friends from a few other countries. The first sergeant with a rumpled uniform even set off a few small fireworks that he lit with his cigarettes. He wasn’t a bad guy, either, but I never felt comfortable around him, and I rarely smiled around him, which was unusual for me. I almost always smiled, but it’s difficult to override an uncomfortable feeling around someone after they’ve bullied you. It’s as if you’re on edge around them, like having PTSD, but only around certain people. I’d still defend him and help keep him safe; that’s how effective teams treat people.

We had fun, and the British captain had a lot to drink. We left him taped to a pole under the American flag, naked, and wrote “More Tax for Tea” on his chest with a red marker. I left Egypt in August of 1993, where I received the greatest honor of my military career. AT-4, my platoon from Desert Storm, had pulled some favors and got me back with them for the last six months of my service in Fort Bragg. They even had a plaque custom engraved from me. “From All the Guys in AT-4,” it said above an Expert Infantry Badge. They were like family to me.

I began college January 17th, 1994, the Tuesday after a three-day holiday weekend that honored Martin Luther King on his birthday. At night and on weekends, I worked as an Emergency Medical Technician with an ambulance team on weekends.

Within six months, I was Co-Captain of the university’s wrestling team. I graduated in three years, with honors. I’m most proud of my service, though. I became a volunteer “Baton Rouge Big Buddy Program.” They trained volunteers and screened them for safety, then paired them with Little Buddies whose mothers wanted them to have a positive male role model in their life. Pa Pa would have been proud of me, even though he never learned what happened to his Little Buddy.

Shortly before I graduated and left Louisiana for the last time, I wrote an article about the important work they do to LSU’s newspaper editor. They printed it, and listed my name as “Magik Partin.” It’s true. You could look it up.