Wrestling Hillary Clinton

But then came the killing shot that was to nail me to the cross.

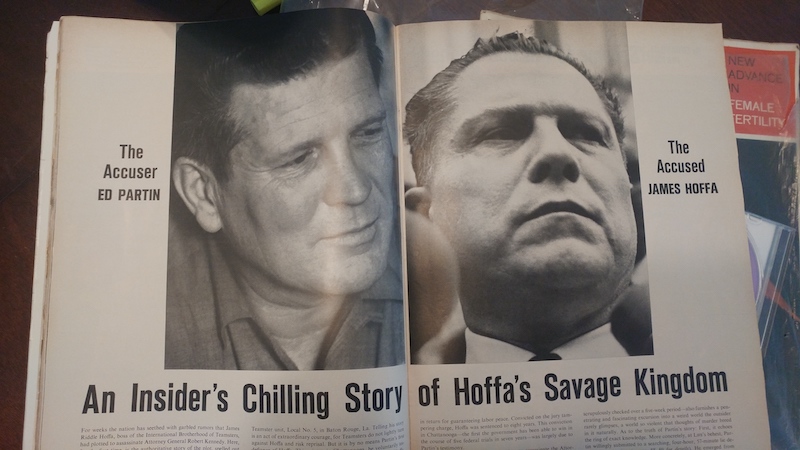

Edward Grady Partin.

And Life magazine once again was Robert Kenedy’s tool. He figured that, at long last, he was going to dust my ass and he wanted to set the public up to see what a great man he was in getting Hoffa.

Life quoted Walter Sheridan, head of the Get-Hoffa Squad, that Partin was virtually the all-American boy even though he had been in jail “because of a minor domestic problem.”

– Jimmy Hoffa in “Hoffa: The Real Story,” 19751

As of 09 January 2025, this is mostly true; I’ll come back to that after two intertwined stories that continue to shape history.

I’m Jason Partin. Thirty four years ago, Hillary Clinton pinned me in the second round of the 145-pound finals match of the Baton Rouge city high school wrestling tournament. I almost won in the first round, but he escaped my cradle by kicking so hard that he broke my left ring finger, just below the middle knuckle. It healed awkwardly, and to this day my two middle fingers point away from each other, and look like Dr. Spock’s “live long and prosper” salute in Star Trek. I’m a close-up magician, so for thirty years I’ve been asked about that hand, and most people laugh when I say Hillary Clinton broke it. They assume it’s part of the act, but it’s not: wrestling Hillary Clinton is the my proudest moment of my life.

The joke about Hillary was that he was like Johnny Cash’s song, “A Boy Named Sue,” a kid who grew up tough and mean because of his name, but he was a hairy black dude bursting with muscles, and faster and stronger than most 18 year olds. I was 17, lanky, relatively weak, with negligible underarm hair and a face dotted with pimples. But no wrester had broken my cradle in almost a year, and by the time I stepped onto the mat to face Hillary I had pinned 36 opponents that season, a few with the half-nelson, but most with my cradle.

The cradle wasn’t a move Coach used himself, probably because he had stubby arms that wouldn’t easily reach around an opponent’s head and leg. His signature move was the half-nelson, but he had coached for more than forty years and knew a thing or two about all types of wrestlers. As one author for USA Wrestling reverently said in the 90’s, not knowing Coach would pass away in 2014 with Alzheimers, “Coach Dale Ketelsen has forgotten more about wrestling than most of us will ever know.”

Coach showed me how use my relatively large hands and spindly arms to have the strongest cradle in all of Baton Rouge, maybe even in all of southern Louisiana. The trick was to not hold both hands together like a handshake, but to lock them with thumbs flat against the first fingers (“A wrestler looses 15% of his strength if he thumb if out”), and, instead of squeezing harder, move your hands away from your body, bringing your elbows together like pivot points of a bolt cutter (“An opponent’s legs are stronger than your arms”). I was a senior taking physics that year, and the bolt cutter example stuck in my mind, not because of a textbook or charismatic teacher in front of a chalkboard, but because I had hands-on experience and saw immediate results. I began pinning people with Coach’s trick the same day he showed me, and I didn’t stop all season.

Armed with physics and with Coach in my corner, I clawed my way from loosing all 13 matches my sophomore year to being seeded third in the Baton Rouge city tournament, with an impressive record of 56-12. Two days and three matches later, I was 59-12 and stepping onto the mat to face Hillary Clinton, captain of the Capital High Lions, the returning three-time Louisiana state champion. He was undefeated almost two years, formidable enough to place in summer freestyle nationals against kids from Iowa and Pennsylvania who grew up with the sport. (Coach was from Iowa, and practically introduced wrestling to Louisiana in 1968; my school, Belaire, didn’t have a program until 1981.) I spent most of my senior year focused on one thing: wrestling Hillary Clinton.

He was up 3-1 when I took took him down in the first round by sprawling and spinning behind him, catching his head and leg in my cradle. I was the first person to score on him all weekend, and it must have pissed him off, because he grunted like an animal trying to rip its leg from a coil-spring trap. He kicked against my hands with the cadence and urgency of a 50 caliber machine gun trying to destroy a charging tank, but with much more force; when I felt my finger snap it less like physical pain, and more like the pain of lost hope, but I’m sure it would have hurt like hell if I weren’t wrestling. I clung to my surviving thumb and two fingers, but with what teammates called my kung-fu grip weakened, Hillary broke free, stood up, and turned to face me with the speed I had grown to respect. The referee awarded him an escape point.

The score was 4:3. I was still down, because I hadn’t held his shoulders above the mat long enough to score back points. We were face to face again, Hillary’s strongest position, and his eyebrows furrowed with anger; I had never seen him angry before, and I only had the smallest fraction of a second to realize that before the buzzer sounded. The referee pointed us to our corners. I had lost my chance: people make mistakes when angry.

Jeremy, our 140 pounder and co-captain of the Belaire Bengals, handed me a fresh hand towel. I wiped the sweat from my eyes, only to have more pour down my forehead, pool in my eyes, and drip off my nose and chin. I alternated between shaking my limbs to stay limber and dabbing sweat off my face, mindful of the break; the knuckle was a swollen, and my ring ginger useless rigid plank. Coach asked, and I said I was fine. Coach nodded and stepped back. I wanted to face Hillary while he was still riled.

My breath whooshed in and out through pursed lips and stared at Capital’s corner. Two of the maroon hooded Lions dried each of Hillary’s arms while he bounced and shook his limbs like a mirror image of me. I focused on his coach, a spherical mountain of an African American man, and tried to decipher his hand gestures. He had never wrestled, and the Lions never participated in all-city practices, so many of their signs were different than any other school I knew. Capital High was near the downtown Louisiana state capital building, a dilapidated school with peeling maroon paint, and a dingy gym with a duct-taped purple and gold mat Coach had given them after LSU disbanded their team after 1979’s Title IV law.

We used to see the them running up and down the capital building’s 34 flights of narrow art deco steps in a line of ascending weight classes, like maroon hooded Matryoshka dolls, with Hillary leading the charge and their coach standing at the base near the old civil war museum, and a few buildings that were still pot-marked from yankee bullets; he was too big to fit in the narrow stairwell. Hillary always ran an extra round up and down, just by himself. He probably ran when no one was there to see him.

Hillary listened intently and nodded after each gesture of the mountain’s massive hands. Coach and Jeremy let me be. Seconds later, the referee called to us, and I trotted back to the center of the mat. Hillary won the coin toss, and of course he chose neutral. We each put one foot forward and faced off. The ref stood poised, whistle in mouth, with one hand raised.

I focused on Hillary’s hips. Coach only gave a handful of nuggets of wrestling advice in the three years I had known him at that point, and one was to watch an opponents hips, not their eyes or hands, because where their hips went, they went. That was advice from an Iowa coach when Coach left as an alternate on the olympic team, at a time in history when Russians were dominating the sport because they focused on taking an opponent off their feet with bear-hug throws, like Hercules defeating Antaeus by lifting him above Mother Earth to severe his source of strength.

“But to do that,” Coach told us, “they need to get their hips close to yours. Get you to overreach, so they can step in close.”

He’d pause and let that sink in, raise a stubby finger, and say, “The Russians realized that if you break a man’s stance, you can do what you want to him.” He’d put down his finger, and finish, “Don’t break your stance.”

I saw him say that the same way three times, once at the beginning of each season. He’d stop talking and demonstrate a strong stance, which he compared to holding a shovel so you could dig heavy dirt on a farm all day, legs bent and thighs strong so they would never fatigue. You could shovel pig shit all day like that, another coach once quipped about Belaire’s stance.

“Vince Lambarti said that fatigue will make a coward out of anyone,” Coach would remind us two or three times a year.

Armed with that knowledge, a few of us ran cross-country track or swam, just for extra exercise. A few hit the football team’s weight room after wrestling practice. A couple of us did all of the above, and I, per Coach’s old-school suggestion, I spent idle time crumbling pages of each day’s Baton Rouge Advocate into tight balls, littering them on the floor in front of a black and white television late at night. I was in remarkable physical condition – a few months later I’d be disappointed by the U.S. army’s basic training, advanced infantry training, and Airborne school, all of which were a pale shadow in the light of wrestling. But with my kung-fu grip weakened, my signature move was useless against Hillary and I lost what little advantage I had. There was nothing else to do, so I got into stance and focused on my opponent’s hips.

Hillary was calm and his stance was perfect. In my periphery, I was aware of the referee’s chest and cheeks: sometimes, they telegraph blowing the whistle, giving a fraction of a second advantage before wrestling.

Coach’s most persistent piece of advice was to just wrestle. No matter what happened the previous round or that morning or the weekend before, just wrestle. With everything you have left in you, just wrestle. He never elaborated, he only said “Just Wrestle.”

His words had roots a gold-medal olympian, the most celebrated of a generation; that guy pinned all four opponents in the 1960 olympics, but had barely beaten Coach 4:3 in overtime during olympic trials. Before Coach’s next match for third place, held only minutes after his loss in semi-finals and back when rounds were three minutes each, that legend approached Coach catching his breath in the locker room and said, “Someone will win. It might as well be you.”

Someone will win. For the next two minutes, it doesn’t mater who. Just Wrestle. Of course rules mattered, but they were ingrained deep down from practice and a part of our core. Coach was on the USA Wrestling rules committee, and he had advocated making the full-nelson illegal after a few kids had their necks broken. Rules let you give more, not less. With that knowledge deep down, nestled next to your primal state, just wrestle.

The referee blew his whistle and dropped his hand, and I began wrestling before spectators heard the whistle end.

Hillary was faster and shot a high double that caught both my legs. I sprawled, kicking both feet into the air like a bucking bronco, and slammed my chest onto his shoulders. He resisted with the strength of Atlas, and pulled my legs with all his might. I sprawled again and again, and he held my thighs and tried to push his hips under mine and tried to look towards the sky. But my lanky legs gave me an advantage, a fulcrum that I leveraged to push the weight of the whole world onto Hillary’s broad hairy shoulders. Sprawl by sprawl, Hillary’s arms crept further from his body, and his head began to bow under the force of my sprawl. He was no longer in a good stance, and that’s when I cross-faced him with the force of God.

Hillary’s head turned and he released his grip. My right hand continued moving into a cradle, my body acting from a core with no concept of pain. I began to spin behind Hillary, my left hand targeting his raised left leg, ring finger stuck straight out, but he sprung backwards, towards the mat’s edge, and popped up into a perfect stance.

We kept eye contact and crab-walked back towards the center, a truce-of-sorts wrestlers fall into without discussing it. We were almost to the center when Hillary’s forearm shot to my neck like a rattlesnake snagging prey. He yanked my head forward, wanting me to plant all my weight on my leading foot. Hillary had a lethal head-heal pick, but Coach had told me how to stop him.

“Don’t be a headhunter,” Coach said. He was given that advice from the US Olympic coach, because the Russians used the same head-heel setup. I used the forward momentum generated by Hillary’s yank, and swung my hips under his and shot a high single that took him to the mat; but he sprung back up and faced me so quickly that no points were scored either way. We stood face to face again for the briefest of moments, then he moved so quickly that I don’t recall how I ended up in a bear-hug: I may have blinked.

Hillary caught me on exhale, my lungs almost empty, and he instantly threw me in a beautiful, perfect throw. I watched the ceiling appear in my view, and I watched my size 12, dingy grey and frayed Asics Tiger wrestling shoes rise above my head. They once belonged to Coach’s son, Craig Ketelsen, a 171 pound wrestler in the early 1980’s, and Belaire’s first state champion. I loved those shoes. I watched them fly through the air above my head in slow motion. They temporarily blocked the basketball scoreboard, a late 1970’s giant orange neon monster with dozens of small lightbulbs that spelled out our names and the schools we represented. It had a massive countdown timer so everyone in southern Louisiana could see how many seconds were left in each round.

Craig’s shoes flew past the orange lights in slow motion, memories forming faster than thoughts form words, a pinhole camera snapshot rather than a written description of a moment in time. The shoes passed the scoreboard above Baton Rouge High’s bleachers, and our names flashed into view again. They began to arc back down, a perfect 360 degree circle. I saw the faces of a few hundred fans who paid to see finals on a single mat placed in the center of the gym floor. Our stands were filled mostly parents and teachers who didn’t know the sport well, but almost had looks of awe on their faces. It was a beautiful throw. Some faces were cringing at the inevitable: I was about to hit the mat like a meteor crashing into Earth.

Hillary slammed my shoulders to the mat with a thud that shook the bleachers as if a C-130 Hercules had dropped a 15,000 pound bomb in the gymnasium. Yes, that’s exactly what it felt like. The shock wave reverberated back from the bleachers and I felt that, too. Had I wind left in me, it would have bellowed out. I don’t know if my eyes were open or closed, but my memory is of the same pitch blackness you’d see deep under Earth, in a bunker and in the middle of night.

My body bridged so quickly that Hillary didn’t get the pin: my feet planted the rubber soles of Craig’s Asics flat on the rubber mat, and my long lever legs pushed with everything they had. My eyes, now seeing light, stared to the trellised roof high above Baton Rouge High’s gym floor, and I realized I had to get my shoulders up, quickly, and I heaved with neck muscles strengthened by nine months of weight training, and pivoted onto the top of my head. I had promised myself I’d never get pinned again, and I would die before I broke that promise.

I bridged and Hillary squeezed my chest with the patience of a boa constrictor, bit by bit, waiting for the slightest exhale to squeeze a bit more. His tightening was controlled, calm, and deadly, like when a disciplined sniper takes precise shots at the peak or valley of each breath, focused on his target more than himself. My bridge began to collapse, and I stared at the bright orange clock – upside down then but somehow right side up in my memory today, as if my mind righted it over time – and I saw that I had almost a minute left.

I tried force my right hand between Hillary and me, making a tight fist so that its gnarly knuckles would rasp across his rib cage and cause enough pain for him to loosen his hold, but he only exhaled and pulled himself closer to my spine, compressing my ribs even more. I was burning precious fuel and my bridge buckled a bit, so I focused on saving energy instead.

I couldn’t move. Frozen in space, I stared at the clock, hoping for time to speed up. I didn’t pray. I’ve never been a religious person, and thinking takes up energy better spent wrestling. Instead, I tried to relax and drift closer to my core.

In my periphery, gathered behind Coach and Jeremy, I saw a few guys from last summer’s all-Louisiana junior olympic team. I knew the white t-shirt they were wearing over their different colored hoodies, the shirt we all wore last summer. It was a simple white cotton shirt with plain black letters that formed a chest full of words. Only Chris Forest, heavyweight for the Baton Rouge High Bulldogs, wasn’t wearing one; he couldn’t squeeze his broad torso into an XXL. Next to Chris and two feet shorter was the Bulldog’s team captain, Clodi Tate, the 136 pound city champion as of two matches ago. The summer before, Clodi’s dad, a minister, had found the shirts in a Christian supplies store under the I-110 overpass near LSU. They were printed with Ephsians 6:12, but it wasn’t about religion for most of us, it was about wrestling. It said: “For we wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places.”

The words on my buddies shirts were upside down, but I knew the words by heart. I would repeat them to myself almost exactly a year later, late at night on 02 March 1991, just before my third ground fight inside an Iraqi bunker and a day before our team captured Khamisiyah airport and when the C-130’s dropped two 15,000 bombs onto it and unknowingly unleashed a mushroom cloud of Saddam Hussein’s chemical weapon stockpile. By that afternoon, I’d be covered in melted asphalt and other people’s blood and dust falling from the mile high mushroom cloud in the sky, more fatigued than I ever had been in my life; we had spent three days without sleep and with negligible food, crawling over thousands of melted Iraqi corpses who died along the roads leading to (or from) Kamisiya during the air bombing campaign, fighting survivors dug deep in bunkers (ironically searching for evidence of Saddam’s weapons of mass destruction), and planning to capture Khamisiha and use it to launch a parachute attack into Bagdad. The war ended – officially at least – and the allied forces decided to destroy Khamisiya and it’s fleet of Soviet MiG fighter jets so that Saddam couldn’t use it again. I have no doubt that the words of Ephisians 6:12 are true for me.

Today, the words written on the all-Louisiana team shirt they would ring true for thousands of high school wrestlers every year since then, even the ones who never heard of Hillary Clinton or knew what happened in the 1990 Baton Rouge city finals. The words may have been upside down, but they were already a part of a core state that had no concept of up or down. Whatever I am, it wrestled, and it would die before it quit fighting against rulers of the darkness of this world.

But my body was out of air and Hillary was an unrelenting beast. The guys in my corner began to fade into one dark grey blur, and the clock became a single spot of fuzzy orange light.

I’m not a coward. Vince Lambarti’s words were meant to spark training, not judgement; I first pondered that a few months later, when I saw a hand-written sign above the advanced infantry training field that said: “More sweat in training means less blood in combat.” Less blood, not none. Sometimes hope isn’t enough. The other wrestler wins. Your teammates loose. They weren’t cowards, either. Fatigue is relative.

Our wrestling singlets were skin-tight and exposed our shoulders so there could be no doubt of a pin. The acne on my back protruded further than the singlet, and I felt the bumps contact the mat and push against my skin. My vision blurred, and I could no longer see the orange light, but I saw the referee’s blurred face when he slide beside us with his whistle pinched between his lips. He blew the whistle and slapped the mat. It was over. Hillary Clinton had won.

We stood up and the referee raised Hillary’s hand. The applause and stampeding of feet on the bleachers shook the gym more than the bomb that had gone off earlier. It really was a beautiful throw, and Hillary earned his pin. The Louisiana High School Athletic Association recorded that he pinned me with twenty seconds to go in the second round, and I couldn’t argue with that. Hillary Clinton would go on to win a gold in city and regionals, and then state, still undefeated. I’d never hear from him again.

I walked to Belaire’s corner. Coach stuck out his right hand and took mine. His other stubby but ridiculously strong hand clasped my left tricep. He looked up into my eyes, his squat but unflappable stance a permanent part of him, and he said: “Good job, Magik.”

I nodded. He had shaken my hand and clasped my tricep the same way and said words to the same effect almost 152 times over three years. He only missed a few matches at big tournaments that had eight mats and multiple wresters on deck at once. When he wasn’t there, Jeremy sat in Coach’s chair, and at least one other wrestler was temporary co-captain. We never mimicked Coach’s handshake, it was from a place deeper than we could grasp.

Jeremy, a man of few words but of kind actions, someone who never agreed with the team’s decision to make me co-captain, stood up and offered the chair next to Coach. Surprised, I sat down and accepted the fresh towel in his hand. He had nothing to prove with his gesture; he had dropped to 140 earlier that year to avoid wrestling Hillary and had won his city finals match when I was warming up on deck. Jeremy was the champion, not I. But he stepped behind me, in the corner that was now empty. I sat beside Coach. Another wrestler was on deck. I had a job to do, and nothing else mattered for the next six minutes.

Later that day, I saw Pat, a former Baton Rouge High heavyweight and now their assistant coach, standing with a few other coaches, laughing. He had assisted the all-Louisiana team, but, like Chris Forest, Pat couldn’t fit into the XXL shirt. He always laughed, and at the end of long days in summer camp his laughter kept us practicing longer than Vince Lambarti’s words ever could. I overheard him saying how Hillary held me so hard the only thing I could wiggle were my eyeballs. Everyone laughed at Pat; he could wiggle his eyeballs, and whenever someone was pinned he told that joke and showed what they must have looked like. I had seen it a million times, so I didn’t look in their direction. I was staring at the clock again, unable to remember when I stopped being able to read it.

I thought I was pinned with thirty or so seconds left to go, and I wondered what had happened in those final ten seconds. I wanted to know what my body did when my mind stopped remembering. What does it mean to give it everything you have, or to “be all you can be,” that hokey army recruiting slogan, when you’re out of air, trapped, and your body slides closer and closer to some primal thing that existed before we had thoughts. Somewhere between what you know and who you are, there’s something that nurtures your core and shapes it into an unchanging, permanent, ineffable pinpoint of force stronger than muscles or memories. Belaire Bengals or Capital Lions, Louisiana or Iowa, north or south, black or white: what made your body move when your mind was blank?

In essence, I was contemplating nature vs. nurture.

It had been on my mind a lot that year. My dad was in an Arkansas federal prison for growing a few marijuana plants – a casualty of Reagan’s war on drugs – and my grandfather had just been released from six years in a cushy Texas federal penitentiary; he was a rapist, murderer, thief, adulterer, lier, bearer of false witness, racketeer (I wasn’t sure what that meant), embezzler, betrayer of teammates, and a man who, according to Mamma Jean, crossed the line when he stopped going to church on Sundays; that’s a sin, you know.

Nature vs. nurture, to me, could be explained in ten seconds missing from my memory, and I was more interested in that than anything a gaggle of coaches had to say.

The crowd parted, and Pat’s smile went away. He leaned down and privately asked Coach: What happened? Magik almost had him pinned. He was focused all spring. It looked like he gave up. Is he okay?

Coach replied that I had a lot on my mind, because my grandfather was sick. Coach was a man of few words; Jeremy was loquacious compared to him. He put on the reading glasses he kept draped around his neck, glanced down at the clipboard he always carried, and waddled away to help someone do something. Everyone nodded. All of Baton Rouge had seen the news; Edward Partin was released early because of declining health, and wasn’t expected to live long. My teammates were kind enough to let me be.

Hillary was a beast, but I almost defeated him. Forty years later, I’m still more proud of that than anything I’ve done since. To a 17 year old high school senior with a family I didn’t want to discuss, almost defeating Hillary Clinton in the Baton Rouge city tournament was bigger news than when my grandfather died a few weeks later.

On 16 March 1990, I rode a Honda Ascot 500cc motorcycle to my grandfather’s funeral. I was wearing a white helmet airbrushed with blue letters that said “c/o 1990?,” a jab at overzealous seniors who wore shirts that said, “Class of 1990!” I sported my cherished but gaudy fuzzy orange letterman jacket with blue sleeves a big letter B on the left chest, and I had meticulously adorned it with 36 small gold safety pins, grouped in clusters of five for easy counting; one pin was stood out by itself and made the others more remarkable.

The jacket had an admittedly awkward looking wrestling letterman pin with one man down and the other behind him, Mercury’s winged feet for cross-country track, and the comedy and tragedy faces of theater (because I was a magician who helped build interactive sets, I lettered as a thespian). The safety pins tinkled in the wind when I slowed the motorcycle down and rode along the shoulder, the small engine barely audible over the traffic jam of cars and idling 18 wheel trucks heading towards Greenwood Funeral Home.

My right hand was on the gas side, my left hand was on the clutch side with its middle fingers buddy-taped; for the occasion, I applied two fresh strips of bright white cloth tape that morning. I slowly braked onto the grass beside a paved parking spot and as close as police would allow, turned off the bike, and draped my helmet on the handlebars.

My face shone from lingering pride at media coverage and a small award from Coach and the team that they presented in front of all 380 Belaire seniors. Most athletic. Coach’s award. A few others. There was a color photo spotlight about me in the newspaper about performing magic at Baton Rouge General’s childrens hospital as part of David Copperfield’s Project Magic, a rare instance of a Partin other than my grandfather in the news. After all of that attention, I was unimpressed by the crowds of people and reporters clustered outside of the funeral home. I walked up to Aunt Janice, she bent down to hug me, and we went inside.

Besides the Patin family, the former Baton Rouge mayor was there, and so was the entire Baton Rouge police department, reporters from every major newspaper, a hell of a lot of huge Teamsters, a gaggle of FBI agents, and Walter Sheridan, former director of the FBI’s Get Hoffa task force and a respected NBC news correspondent in the 1980’s, and a surprisingly long lineup of aging brutes from the 1954 LSU football national champion team. Billy Pappas, our first Heismann trophy winner, former pro for the Houston Oilers, and the biggest celebrity on the biggest float in the Spanish Town Mardi Gras parade, was one of the pallbearers; his handsome face was on billboards all along I-10, his bright white smile advertising his dental business, and everyone wanted to see him.

No wonder no one asked about my letterman jacket or buddy-tapped fingers, not even the reporters and television crews supposedly focusing on things like that. The New York Times simply listed me as one Edward Grady Partin Senior’s grandchildren. (They mistakenly said “and great-grandchildren,” but I was the second oldest and knew all of my cousins from both his marriages, proving that even the NY Times makes mistakes.)

Only Walter asked about my fingers. He noticed details, and was good at his job. That’s probably why J. Edgar Hoover and Bobby Kennedy hand-picked him to rejoin the force with one job: get Hoffa.2 For twenty years, he focused on nothing else, and he was a friend – of sorts – to Mamma Jean and Grandma Foster. I barely knew him, but I knew that year he was focused on my grandfather and his final words.

My grandfather was Edward Grady Partin Senior, the president of Baton Rouge Teamsters Local #5, famous for testifying against International Brotherhood of Teamsters president Jimmy Hoffa and sending him to prison. Hoffa had famously vanished in 1975 and was pronounced dead in 1985, and most people assumed my grandfather was a part in his demise. The Partins didn’t think much about Hoffa at all. We called my grandfather Big Daddy, and so did a lot of people in Baton Rouge. He was front page news weekly, with governors seeking his endorsement and corporate managers hoping to avoid his wrath. He drove the economy, shipping all agriculture and oil products to and from Louisiana, and he overtly built the Baton Rouge International Speedway (originally the Pelican Speedway) with materials skimmed from deliveries to construction site all across the south, and until he sold it, he ran the racetrack with the generosity of a man who wanted his neighbors to have good time without being bogged down by cash or rules. Before he went to prison in 1981, political commentators said that he’d become governor if he only had a college degree.

Big Daddy was portrayed by the classically handsome actor Brian Dennehy in 1983’s Blood Feud, at a time when America knew what Big Daddy looked like and therefore Brian was a logical choice. Robert Blake slicked back his hair to look like Jimmy Hoffa, and won an academy award for “channeling Hoffa’s rage.” Some daytime soap opera heartthrob portrayed Bobby Kennedy, but he didn’t win anything for it. Brian could have won an award, but he tainted his public image by stealing valor after his role as sheriff in that years’s “Rambo: First Blood,” and no one wants an asshole like that to win anything. I don’t recall who portrayed Walter, but the producers tried to make his character look like a hero by letting him slap Brian Denehy (Hollywood fabricates details to make people believe someone is a hero), but Walter would never be foolish enough to slap Big Daddy.

The mayor and the football players said a lot of words, and so did a few of my younger cousins. Tiffany, the only one older than I was and a public speaker who was a homecoming queen in Houston the year before, had everyone in tears. So did Jennifer, a younger cousin and another beauty queen in Houston, who talked about how Big Daddy was a hero who saved Bobby Kennedy’s life. After the funeral, when most people got up and flocked around Billy and the aging Tigers, I leaned over and told Walter – who didn’t seem to care about football – that Edward Partin’s final words were: “No one will ever know my part in history.” He agreed that it sounded funny when said out loud, and that Big Daddy was probably right.

Big Daddy’s final words stuck with me, and for the next thirty years I pondered what he meant. Practically every book and film has it wrong, and a lot of the information wouldn’t trickle out until 1992 and memoirs of dying Teamsters in the early 2000’s, so please read this with a clear mind. This is his story, according to what I know so far.

In 1924, Big Daddy was born in Woodville, Mississippi, to Grady and Bessie Partin. Great-grandpa Grady was a lush who ran out on them during the Great Depression, and my eventual grandfather began providing for Grandma Foster (Bessie later remarried) and his two little brothers, Doug and Joe, men I’d eventually know to be as big as Big Daddy. In 1943, a 17 year old Ed and a 12 year old Doug broke into the Sears and Roebuck store and stole all of the guns in Woodville. They hauled them two hours downriver to the city of New Orleans, and found men wanting to buy lots of stolen guns. With a bag full of cash, they bought motorcycles and rode all the way back to Woodville. Doug said the next few weeks were the best of his childhood, but that they were arrested by the Woodville sheriff after speeding through town, hooting and hollering and showing off.

Doug was set free because he was a minor, but the judge gave Ed a choice: join the marines or go to jail. He joined, punched his commanding officer in the face, stole a watch off the unconscious body, and became a dishonorably discharged marine within two weeks of the judge’s decision; he returned to Woodville a free man. He turned 18, and with all the young men away at war, he easily took over the Woodville sawmill union. After the war, when trucks and gas were in supply again, he also ran the trucker’s union of southern Mississippi.

Big Daddy was ruthless and effective. A young International Teamster President named James “Jimmy” R. Hoffa admired his style and told everyone to trust him. In 1954, he and his young wife, Norma Jean Partin (my Mamma Jean) moved to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and Big Daddy began to run Teamsters Local #5 under Jimmy Hoffa. Hoffa was amassing an army and needed lieutenants. His 2.7 million Teamsters paid him monthly dues in untraceable cash, and Senator John F. Kennedy of the U.S. labor relations committee had set his sites on taxing that cash and reigning in Hoffa’s power. In 1960, President John F. Kennedy appointed his little brother, Harvard law graduate Bobby Kennedy, as U.S. Attorney General with two tasks: get Hoffa, and stop organized crime, a new concept in America that the government denied publicly while secretly working to stop it.

By 196, Kennedy’s Cuban embargo had all-but strangled trade with Cuba, but Big Daddy was meeting with revolutionary leader Fidel Castro and shipping arms and boats from New Orleans to Havana. He trained Castro’s generals and a handful of what would have been their special ops soldiers; Big Daddy was legendary at keeping secrets, better than any magician I knew from the Baton Rouge Ring #178 of The International Brotherhood of Magicians (where I was – with quite a bit of pride – the “sergeant at arms”), so I don’t know what Big Daddy trained Cuba’s generals about; I assume it was more than how to organize people, because Castro was pretty good at that already.

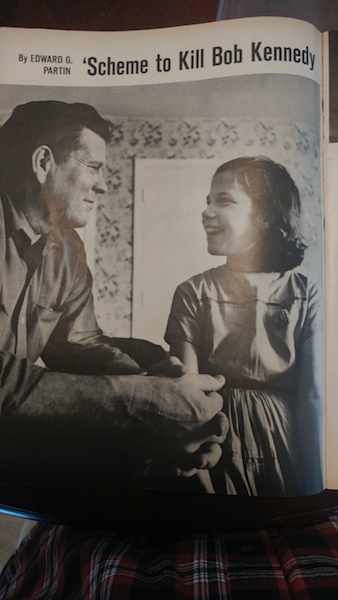

Legendary FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, the cross-dressing anti-communist who used secret recordings of senators and congressmen’s personal lives to blackmail them into prosecuting all suspected communists during McCarthiasm, became interested in Big Daddy and Castro and assigned the New Orleans FBI office to follow him and report what they learned. Hoover’s records of Big Daddy were classified, but they’d resurface in 1992’s release of the John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King JuniorAssassination Report show that in 1962, Big Daddy met with Jimmy Hoffa in an undisclosed location, probably Teamster international headquarters, and Hoffa plotted to kill Bobby Kennedy.

Hoffa wanted Big Daddy to get plastic explosives from a contact they both knew to be Carlos Marcello , the New Orleans mafia boss, who would probably get them from Castro. Hoffa wanted to toss explosives into Bobby’s home, according to Hoover, and this scene was a focal point in 1983’s “The Blood Feud.” The camera zooms in on Robert Blake’s face and torso: he ignores Big Daddy, and wistfully imagines killing Booby. His hand gently lofts an imaginary grenade, and he slowly whispers through pursed lips: “Boom…” He relaxes, satisfied, and smiles.

Big Daddy said he was averse to killing kids, so they shouldn’t bomb the home. Hoffa agreed; and that’s part of why Big Daddy was called an all-American hero. (The scene where the guy playing Walter slapped Brian Dennehy was to show how the FBI motivated nervous witnesses). But the film omitted that Hoffa then said they could recruit a sniper with a high powered rifle, one outfitted with a scope to shoot from afar (back then, scopes were as high-tech and expensive as night vision goggles in the first Gulf war), and that the sniper could shoot Bobby as he rode through a southern town in one of the convertibles “that snot-nosed brat Booby” likes to ride around in and show off. Hoffa often called Bobby “Booby” in public, and at one point lunged at the much-taller Bobby in front of reporters to show who was the bigger man: the film was called “Blood Feud” for a reason. Bobby, in return, pulled no punches in his public pursuit of Hoffa.

Everyone in America knew Hoffa would be suspected if anything happened to Bobby Kenedy. If they used a sniper to kill that snot-nosed brat, Hoffa said, they’d have to ensure he couldn’t be traced back to the Teamsters.

A few months after Hoffa and Big Daddy plotted to kill Bobby Kennedy, Big Daddy helped 23 year old Baton Rouge Teamster Sydney Simpson kidnap his two young children after he lost them in divorce court. (Though he was averse to killing kids, my grandfather seemed okay with kidnapping them; that was the “minor domestic problem” Jimmy Hoffa quipped about for the next ten years.) Sydney and Big Daddy were arrested and put in the Baton Rogue jail. Coincidentally, Big Daddy was also charged with manslaughter in Mississippi, saving their police from searching for him across the state line. Word got out, other charges began to roll in. Big Daddy faced life in prison.

Big Daddy told Sydney, “I know a way to get out of here. They want Hoffa more than they want me,” and when Sydney asked what if he knew enough to help the FBI get Hoffa, Big Daddy replied, “It doesn’t make any difference. If I don’t know it, I can fix it up,” and said, “I’m thinking about myself. Aren’t you thinking about yourself? I don’t give a damn about Hoffa. . . .'” Big Daddy made a phone call, and a few days later Bobby Kennedy had him sprung from jail. (Poor Sydney remained and went to prison, but his words were recorded by attorneys.3 ) Through Walter, Bobby offered Big Daddy immunity if he would infiltrate Hoffa’s inner circle, and find “something” or “anything” to remove Hoffa from power.

Bobby acted out of desperation. He and FBI director J. Edgar Hoover had spent untold taxpayer money supporting 500 agents on their Get Hoffa task force for almost ten years. Journalists called their Blood Feud the longest, most expensive, and fruitless pursuit of one man in any government’s history (that was probably true until Saddam Hussein, or perhaps Manuel Noriega, and then Osama Bin Laden, until Seal Team 6 ended that pursuit). Bobby had a black eye in the face of his big brother, and he probably would make a deal with the devil to get Hoffa. Big Daddy accepted his offer and called Hoffa to set up a meeting. Hoffa asked his right-hand man, Chuckie O’Brien, to toss him $20,000 in cash from the safe for legal fees – that’s how much he trusted him – and Big Daddy began telling Walter everything he saw and heard behind closed doors. As Chief Justice Earl Warren would write, Edward Partin “became the equivalent of a walking bugging device.” For the next two years, the Get Hoffa Task Force revolved around what he told Walter, and Walter wrote transcripts for Hoover, and Hoover wrote summaries for Bobby; at one point in mid November, Bobby and Hoover escalated the report about Big Daddy and Hoffa to President Kennedy, who said there were always threats.

On 22 November 1963, a few months after Big Daddy made his deal with Bobby, President John F. Kennedy was shot and killed by at least one gunman as he rode through downtown Dallas in his open convertible with the Texas governor and his wife. Less than an hour later, Lee Harvey Oswald was arrested for shooting and killing Dallas police officer J.D. Tippit with a bulky .38 revolver, about the size of a standard police issue, outside of a movie theater a few blocks away. Oswald was arrested, and police immediately charged him with killing both Tippit and President Kennedy.

Oswald was a New Orleans native and Castro sympathizer, a former marine, and a defector to The Soviet Union who returned to New Orleans with a Russian bride and their baby girl – inexplicably paid for by the FBI – who trained in the Baton Rouge civil air force under the alias Harvey Lee. Before being read his Miranda Rights, Oswald exclaimed: “I am only a patsy!”

He was escorted to jail, and FBI and Dallas police looked where he worked, the 6th floor of a downtown book repository overlooking where Kennedy was shot, and they found his 6.5mm Italian army surplus carbine, modified by a Dallas gunsmith to include a high-powered scope. (Oswald had inexplicably moved from New Oreleans to Dallas, and was given a job in the book repository.) Police matched the 6.5mm rounds with a failed assassination attempt on a Dallas-based army general a few months before, a missed shot through this office window that embedded in a wall near the general’s head (Oswald was a bad shot), and evidence mounted. Photos of him with his pistol and that rifle were found, and his pro-Castro pamphlets were collected.

Hoffa, upon hearing the news of Kennedy’s death and Oswald’s arrest, was in Florida in a pre-planned meeting, and he told his entourage: “Bobby’s just another lawyer now.” He told all Teamster halls to keep American flags at full mast, and said he was glad President Kennedy was dead.

Kennedy’s death overshadowed officer Tippet’s murder, but Dallas knew that they lost a hometown hero. Tippet was a decorated police officer, a WWII soldier who won the bronze star, and a respected family man in his neighborhood; Oswald would probably be a target for revenge. He was heavily guarded so that he could stand trial, both for the core of America’s justice system of innocent until proven guilty by a jury of your peers, and to learn who, if anyone, had orchestrated Kennedy’s assassination and made Oswald say, “I’m just a patsy,” but police failed to protect Oswald, so we never will learn what more he had to say.

Two days after being arrested, policed escorted Oswald out of the police station in handcuffs and on international live television, and Jack Ruby, a Dallas nightclub owner, air force veteran, low level mafia runner, and associate of Hoffa and my grandfather, walked through the police station, past a few dozen armed police officers outside, slid a Colt .38 “detective’s special” handgun from his trenchcoat pocket, and shot Oswald in the stomach point-blank. Despite all of the police protection, Ruby was so close to Oswald that he could shot a double leg takedown, had he been a wrestler instead of a hitman with a plan to shoot Oswald at least a few times. He only got one shot off before police subdued him.

Live television captured Oswald’s death: millions of people saw someone killed on live television for the first time. A Pulitzer-prize winning photo showed Oswald doubled over in pain, and Ruby’s middle finger on the trigger, a mafia technique for close-up kills. (In theory, when shooting from the hip with a stubby gun, you’re more accurate if you point your trigger finger along the barrel and pull the trigger with your middle finger; killers say it’s the ultimate Fuck You.) A few hours later, Oswald was pronounced dead; Ruby would eventually be found guilty of first-degree murder by a jury and sentenced to life in prison.

Vice President Lyndon Johnson became president. He escalated Kennedy’s 50 or so thousand “special forces,” championed by Kennedy to minimize loss of life in the decade-old, CIA-led mission to halt the spread of communism, and soon 500,000 drafted soldiers fought in the Vietnam police-action with billions of dollars in high-tech equipment, prompting some people to claim Kennedy’s death was motivated by internal ideologies and financed by lucrative military contracts. Others claimed the mafia, a new term for organized crime that was a new concept in America, was to blame. And of course, many people suspected Jimmy Hoffa and the Teamsters, though few other than Hoover and Bobby knew of his links to the heads of mafia families (I don’t think even Walter knew the extent). To quench the growing fire, President Johnson asked Chief Justice Earl Warren to oversee a committee digging into possibly conspiracies to kill President Kennedy.

Ten months later, the hastily assembled 1964 Warren Report mistakenly – or intentionally – said that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone when he shot and killed President Kennedy, and that Jack Ruby acted alone when he shot and killed Oswald. A second, longer study was planned behind the scenes; it would become the 1979 JFK and MLK Assassination Report, but for some reason it was kept classified. The federal government’s official verdict for a man who never stood trial adhered to the 1964 Warren Report; inexplicably, the part in Hoover’s report about Hoffa and Big Daddy’s plotting to recruit a sniper with a scope to shoot Bobby Kenedy as he rode through a southern town would be classified until 1992. I don’t know why.

Around the same time the Warren Report was released to public scorn – few believed one man could do so much damage, especially one with abysmal military marksmanship records – Jimmy Hoffa’s jury tampering trial was underway in a small courtroom in Chatanooga, Tennesee. It was the Test Fleet case, a charge of jury tampering in 1962, from soon after Big Daddy was sprung from jail. Hoffa was annoyed, but confident of another win against the nipping little snot-nosed brat. Bobby and Walter and a team of federal agents reporting to Hoover lurked everywhere. Big Daddy was in Hoffa’s corner of the courtroom, near Chuckie. When he stood up as the surprise witness, Hoffa’s otherwise stoic and calculating face went pale, and he exclaimed “Oh God! It’s Partin!” in front of the jury, probably sealing his fate before Big Daddy gave his testimony.

Big Daddy smiled the smile that made people trust him, and in a calm southern drawl captured pretty well by Brian Denehy in Blood Feud, Big Daddy told the jury that Hoffa suggested he bribe a juror by tapping his back pocket and implying that $20,000 “should do it.” There was no other evidence. A few days later, the jurors deliberated less than four hours and found Jimmy Hoffa guilty of jury tampering. The judge sentenced Hoffa to eight years in federal prison based solely on Big Daddy’s word.4

At Hoffa’s trial, Hoover announced that he’d assign extra federal marshals to protect the Partin family from inevitable retribution. He then released parts of FBI records to Life magazine, and told media that Big Daddy thwarted a plot by Hoffa to bomb Bobby’s home using plastic explosives. Edward Grady Partin was dubbed an all-American hero, and Big Daddy and Mamma Jean’s five children – my dad (Edward Grady Partin Junior), Janice, Keith, Cynthia, and Theresa – were showcased alongside the Johnson family, by then known as the first-family of America’s new president. Mamma Jean’s absence from photos and quotes wasn’t discussed, though she’s mentioned extensively in court records as Big Daddy’s “estranged wife.” (Mamma Jean had fled him and hid her children in fishing camps throughout Louisiana; Walter, who was good at his job, found them and made a deal with her in exchange for photos with my dad and his siblings, and she maintained her 5th Amendment right). To America, the star witness against Jimmy Hoffa was a trustworthy family man who risked the lives of his children to steer America in the right direction by standing up to corrupt unions and the newly recognized mafia: an all-American hero.

Big Daddy returned to running Local #5 with federal immunity. (Secretly, Bobby moved Mamma Jean and their five children to a house in Houston, part of Big Daddy’s deal, and Hoover had a squad of federal marshals following my family wherever they went.)

Over the next two years, Hoffa’s army of attorney’s attacked Ed Partin’s credibility in national media, claiming he was a Castro sympathizer, murderer, dope fiend, and thief. He had perjured. He had “raped a Negro girl,” but he was let free because one juror would not vote guilty; Doug said that juror told everyone, “Ain’t no white man should go to jail for nothing he did to a Negro girl.” (He used another word.) But no one could find records for all the crimes, as if the proof had vanished like a magician’s tiny red handkerchief.

It wasn’t a lack of resources. Hoffa had $1.1 Billion in untraceable cash from monthly dues – a ridiculous sum in 1950’s money – that Hoffa used as the Teamster pension fund when work was slow, and when work was good he invested it like a pro. He lent $121 Million to mafia families so they could build casinos and hotels, but only if they hired Teamster truckers to haul building materials, guns, and a slew of things. And he lent to Hollywood film producers, so they could hire Teamster trucks to haul equipment and trailers to house actors. He had almost 3 million fiercely loyal Teamsters motivated to keep him in power, mafia bosses who wanted to keep him in control of the pension fund, and the best lawyers money could buy.

Frank Ragano, known as the “lawyer for the mob,” had only had two clients other than Jimmy Hoffa, New Orleans mafia boss Carlos Marcell and Miami mafia boss and Cuban exile Santos Trafficante Junior, men known for their ruthless tactics and debts to Hoffa (Marcello alone owned $21 Million from money he borrowed to build New Orleans hotels). Hoffa used his lawyer’s contacts and everything in his power to discredit Big Daddy or intimidate him into recanting his testimony. They began to spread word that all mafia debtwould be forgiven if “someone” could do “something” to get Edward Grady Partin to change his testimony, or to have Hoffa’s case thrown out because they could prove Bobby Kennedy violated the fourth amendment in his zest to get Hoffa.

The 4th Amendment was hand-written by our founding fathers in 1789 to protect Americans from a police-state. It says: “The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.” Ragano and other Hoffa attorneys argued that Bobby violated the second amendment by sending Big Daddy into Hoffa’s camp to find “something” or “anything” against Hoffa. Walter’s assignment for Big Daddy was a clear violation of the fourth amendment, and Hoffa’s lawyers spent two years preparing for that battle.

But they failed. Chief Justice Earl Warren, a household name by then, oversaw “Hoffa vs. The United States,” a landmark case still taught in practically every law school in America today, because a bent 4th Amendment weakens American freedoms like a broken finger weakens a kung-fu grip against Hillary Clinton. Of nine justices, only Warren dissented against using Big Daddy’s testimony (two abstained). I don’t know why.

Jimmy Hoffa, one of the world’s most powerful people, began an 11-year prison sentence in 1966. For his work detail, he spent six years pounding mattresses eight hours a day, six days a week; at night, he wrote and iterated his autobiography, and plotted how to regain control of the Teamsters.

Coincidentally, Jack Ruby died in prison that year from lung cancer, after claiming the FBI poisoned him with cancer-pills (Ruby was a lifelong smoker). For two years, his statements vacillated between him loving President Kennedy and wanting to protect his widow from seeing a lengthy trial, saying he was an avenger for Kennedy’s death, to spikes of moodiness and ranting about conspiracies and recanting his earlier statements. Though I can’t find the reference today, what sticks most in my mind is what I’d read in 1993, in a bulging dossier given to me by someone I truest; it was a photocopied 1965 small-town news article verified by an FBI agent whom I also trusted, and the reporter quoted Jack Ruby as saying: “No one will ever know my part in history.”

In 1971, Jimmy Hoffa published his first autobiography from prison. In it, he ranted about Big Daddy and that snot-nosed spoiled brat Booby, and said the situation was too complex for even Hollywood to swallow (he would know: he had been financing Hollywood films for years), so he wrote all of the characters as if writing a script. He then sent word to President Nixon, who was up for re-election, and offered his endorsement and the support of almost 3 million voting Teamsters if Nixon would offer Big Daddy a pardon for perjury, allowing him to recant his 1964 testimony without penalty and free Hoffa.

Richard “Dick” Nixon called WWII hero and star of 40 Hollywood films, Audie Murphy, “America’s Most Decorated War Hero,” a legendary infantryman with 278 confirmed kills against Nazi forces in practical hand-to-hand machine-gun combat to protect his teammates from an entire company of soldiers acting on the evils of Hitler’s Nazi party. He was awarded every medal America had to give; some of them multiple times. If anyone could get something done, it would be Audie Murphy. Even mafia hitmen with names like Frank “The Irishman” Sheenan spoke highly of Audie: 278 kills is remarkable by any standard.

Dick sent Audie him to Baton Rouge with a draft pardon, asking him to convince Big Daddy to free Hoffa. Audie flew his small plane there and landed his small plane in the same airport Harvee Lee had used ten years before. A few weeks later he escorted Big Daddy to San Diego – where Audie lived and raced horses at the Del Mar racetrack – and they drove to Nixon’s beachfront home north of Camp Pendleton, perched on the cliffs above a surf spot humorously named “Slippery Dick’s. Big Daddy refused again.

Audie persisted, and returned to Baton Rouge in his plane with four colleagues; he was broke by then, suffering from PTSD, and on a national crusade to educate America and the returning Vietnam veterans on the suffering that even he experienced as a result of combat; he was a good person, and did the best job he could. But he was desperate, and he left his plane at the airport and met with Big Daddy and begged him to free Hoffa, so that Hoffa would finance another film for the aging actor and war hero (being a celebrity doesn’t put bread on the table or hay in the stalls). perhaps a followup of his family’s film, “To Hell and Back,” could introduce the long-term consequences of war to voters and get us to stop voting for assholes and dumbasses (those are my words: Audie didn’t curse or accept lucrative advetising endorsements for booze or tobacco, because he promised his mom he’d be a good influence on kids who looked up to him). Audie may have said something to alarm Big Daddy; two weeks after Audie left, on 28 May 1971, his plane went down in Virginia for unknown reasons, killing Audie and all four passengers instantly. In Uncle Doug’s 2019 autobiography, “From My Brother’s Shadow: Teamster Douglas Wesley Partin Tells His Side of The Story,” he says that if you knew Ed Partin, you’d have no doubt that he was behind killing America’s most decorated war hero and an airplane full of innocent passengers. I agree with Doug, but I’m biased, and so was the mafia: if Big Daddy could kill Audie Murphy, he was a man even the mafia feared.

After Audie died, America lost a true American hero. Hoffa donated at least $1.4 Million to President Nixon’s campaign and endorsed a republican for the first time in Teamster union history; after winning re-election, Hoffa pardoned Hoffa on the condition that he remain away from the Teamsters for eight years, and help Nixon’s image by traveling to Vietnam to negotiate the release of American POW’s.

(Incidentally, after Audie’s death and all of its publicity, my 17 year old dad, Edward Grady Partin Junior, moved from Mamma Jean’s house in Houston to Grandma Foster’s house near the airport, rekindling his relationship with Big Daddy and becoming Glen Oaks High School’s drug dealer. He met my mom, a 16 year old girl and junior at Glen Oaks, who had an abusive father and was experimenting with marijuana to quiet her PTSD. A few months later she lost her virginity to my dad. According to doctors at The Baton Rouge General Hospital, I was born ten months later, on 05 October 1972, at 9:36 in the morning, weighing 8 pounds and 9 ounces. I never met Audie, but I’ve read everything he’s ever written, and think I would have looked up to him, even though he never made it through Airborne school, what he called “the paratroops.”)

Hoffa famously vanished from a Detroit Parking lot on 30 July 1975, creating one of the FBI’s most famous unsolved mysteries. Coincidentally, American began withdrawing from the Vietnam conflict ended that year; almost 56,000 Americans had died, and so did 4.5 million Vietnamese; no one knows why. President Nixon was impeached and resigned, and President Ford pardoned him a few years later for reasons that never interested me enough to read about.

In 1979 and behind closed doors, the U.S. congressional committee on assassinations completed the JFK and Martin Luther King Junior Assassination Report after fifteen years of diligence. For reasons I don’t know, President Jimmy Carter kept it classified. (He was dealing with the oil crisis and 300 Americans held hostage on a runway in Iran, and a failed rescue attempt by the nacent anti-terrorist team Delta Force, among many other things, and no one knows what was happening behind closed doors, other than perhaps J. Edgar Hoover.) Presidents Ronald Reagan and George Bush Senior also kept the reports classified.

Over Christmas and New Years, 1989-1990. the world watched President Bush Senior send America’s Quick Reaction Force, the 82nd Airborne, parachuting into Panama to overtake Noriega’s government (two Delta force guys and some SEALS died). Eight months later, on 03 August 1990, President Bush Senior sent the fatigued 82nd Airborne to “draw a line in the sand” against Saddam Hussein after Iraq invaded Kuwait with 400,000 soldiers and the world’s largest fleet of tanks since Hitler’s forces in WWII, and then turned their sites on Saudi Arabia. Eighteen hours later, a few C-141 airplanes full of young paratroopers armed with machine guns, and a few platoons of three-man Humvee teams armed wtih 50 caliber machine guns and TOW II anti-tank missiles, landed in the 117 degree August heat of Saudia Arabia; they heard the news about a line being drawn, and quipped that they were only “speed bumps in the sand.” But they did their job, and they held their ground and soon more than 560,000 allied troops from a coalition of countries stood behind them, with General Stormin’ Norman Scwartzcoff in their corner. Nine months later, the allies liberated Kuwait, and most Americans returned home alive.

In 1993, three years after Big Daddy died, President Bill Clinton released the first part of the JFK and MLK Assassination Report, but only after 10 million people saw Oliver Stone’s film, JFK, based on New Orleans district attorney’s memoir “On the Trail of Assassins.” Voters demanded that the report be made public; sometimes democracy works, and memoirs can make a difference. The partially released JFK assassination report reversed The Warren Report, and concluded that though they didn’t have proof and therefore it’s inconclusive (seriously – you can’t make that up), the three leading suspects with the means and motivation to kill President Kennedy were Jimmy Hoffa, Carlos Marcello, and Santos Trafficante Junior. The parts about Big Daddy were discussed ad nauseum and finally deemed a coincidence.

A deluge of books and films flowed following the partial release of the JFK and MLK Assassination Report. Most were crap. They made the waters of history murky, and the list is too long to bother with. The full report was kept classified. Each president released a bit more, but part is still confidential to this day. I don’t know what Carter, Reagan, Bush Sr, Clinton, Bush Jr., Obama, Trump, Biden, and then Trump again saw that they wanted to prevent the public from seeing; if I were president, I’d want everyone to know how to stop killing presidents. But what do I know about presidents?

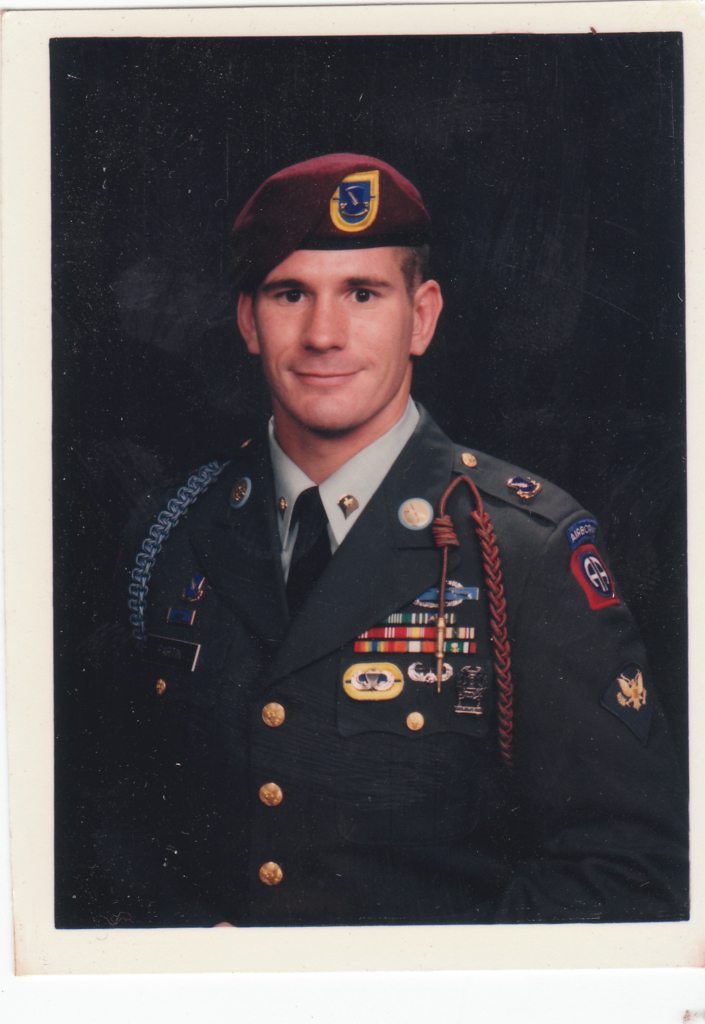

I was a 19 year old paratrooper on President Clinton’s quick-reaction force in 1992. I had already served on President Bush Sr’s quick reaction force, the one famous for drawing a line in the sand against Saddam Hussein’s fleet of tanks, and I sported a chest full of medals that would have blown my 17 year old mind if I were to see me two years later. My dress greens were adorned with shiny silver parachutes with wings, helicopters with wings, and a few other things with wings (Airborne likes wings). My lapels shone with the blue and gold crossed muskets of an infantrymen, and fancy braided ropes dangled from my shoulders and looped under my arms. A medal from the prince of Kuwait, a desert palm tree with two crossed scimitars, was prominent on my chest. A few rows of colored ribbons were where my 36 gold pins had been two years before; I still don’t know what they all meant, though paperwork for one credited me and a buddy with capturing some of Saddam Hussein’s Republican Guard in a bunker outside of the Khamisiya airport.

I wore a maroon beret with a flaming gold sword across a blue shield, and I sported spit-shined jump boots. My shoulders were adorned with two red and blue 82nd Airborne patches – a big AA topped with an Airborne tab – one on my left for my current unit, and one on my right that was mine forever, saying I had fought in combat with the 82nd Airborne.

The AA stood for “All Americans,” a name given to the 82nd Infantry when they were formed to fight WWI, surprisingly soon after the civil war, and the first time in American history that we had soldiers from every state in the same military unit. To heal wounds, the 82nd was dubbed The All Americans, and they united to fight a common enemy. In WWII, they were reactivated and became America’s first paratrooper unit, the forefathers of modern special forces.

I wore my uniform with less pride that I worn Belaire’s letterman jacket when I represented that team. I was an All American with a uniform that said so, just like I had been an all-Louisiana wrestler sporting a simple white t-shirt with plain black lettering that told the world what I stood for. But I was disappointed by the lackluster honor of people claiming to be America’s Guard of Honor, more of a feeling of lowered expectations than anything specific, though I somehow knew it was related to Ephsians 6:12. I spent idle time reading books, and training with the Fort Bragg wrestling team. I was 187 pounds by then, and a below-average wrestler who didn’t make the official team, a big fish in the Louisiana pond but a minnow in the ocean of competition from Fort Bragg, the world’s largest military base in terns of population, home of the 82nd Airborne and Delta Force.

I did better as a paratrooper. Like I earned second in city finals, I earned runner up for the 82nd’s soldier of the year, second out of around 12,000 paratroopers – though I’m still most proud of wrestling Hillary Clinton, and Coach shaking my hand and telling me I did a good job. I began to hob knob with generals. I kept my opinions of Big Daddy to myself, but even a kid like me could see the irony of being a bona fide All American hero, not just a media portrayal of one who was celebrated by people who never bothered to read Hoffa or Walters’s books.

And it gets funnier. In the fall of 1992, I was being reviewed for a diplomatic passport to serve in the Multinational Force and Observers in Sinai, Egypt, an entity created by President Jimmy Carter’s Camp David accords and part of why he earned the Nobel Peace Prize. I was to be an unarmed “communications liaison,” a so-called expert in linguistics and modern technology like the SINCGARS radio systems and nascent and unknown GPS satellite system. The FBI flagged me as a person of interest because of my name. I cleared, and when the JFK Assassination report was released I read it and anything lying around I could get my hands on. Those reports, combined with the deluge of books in the mid 90’s and a few stories from Uncle Doug, led me fill in the blanks myself.

But I didn’t think much about it. I had a series of jobs to do, and thirty years passed faster than Hillary Clinton’s hands could snake a head-heal pick.

By 2019, I was a middle aged man with an unimpressive job title and an impressive collection of scars and awkwardly healed bones that I rarely discussed. I wore nondescript clothes to work, managed an innovation laboratory at the University of San Diego, and led a few courses in engineering, physics, and entrepreneurship. USD started a new “cyber-security” program and combined it with the newly named Shiley-Marcos School of Engineering, and portly professors with PhD degrees in leadership and tenured jobs gave long speeches about what it takes to serve your country. (I had no PhD, and was not invited to say anything at the ceremony). My seven years was reduced to a few sentences at the beginning of a three page cirruculum vitae, and dwindled down to a single line buried in my Linkedin profile. I liked my job, and student reviews said I was good at it.

I hadn’t thought about Big Daddy in years, but my interest was rekindled in the spring of 2019 because the internet was ablaze with advertisements about a film from producing legend Martin Scorcese about Jimmy Hoffa’s final years. It was called “The Irishman.”

Scorcese spent around $257 Million to make and market “The Irishman,” a movie adapted from the 2004 memoir “I Heard You Paint Houses” by Frank “The Irishman” Sheeran. Frank was a former WWII infantryman, Teamster leader, mafia hitman, and colleague of my grandfather. They knew each other well, and Frank mentions my grandfather throughout the book, and, like almost any soldier of his generation, he dwelled on Audie Murphy’s loss and Nixon’s interest in having Hoffa free POW’s. But Frank wasn’t a good person. He claimed to have painted the wall of a Detroit suburb home red with Hoffa’s splattered blood, hence the name of his book (a house painter was mafia lingo for a hitman.) Because he mentions Edward Partin, and because Hoffa’s prison sentence had to mentioned in any film about Hoffa’s life, Big Daddy had a small part in The Irishmen to help move the plot along. Scorcesese omitted the chapter about Nixon and Audie and Big Daddy; I don’t know why, but I assume it was like Jimmy Hoffa said, that it was a complex story and too crazy, even for Hollywood. And, like how Hoffa financed films that planted anchor biases into America’s collective mind, I assume whomever invested a quarter of a billion dollars in the definitive film about Jimmy Hoffa had an agenda, even if they didn’t realize it.

The burly Italian-American actor Craig Vincent, a veteran of a small role in Scorcese’s Casino, was asked to portray “Big Eddie Partin,” a simplified Irish version of Big Daddy. He took his role to heart, and called our family to research his role. Keith Partin was easy to find, because Kieth was listed on the International Brotherhood of Teamsters website as current president of Baton Rouge Local #5. (Teamsters breed Teamsters: Doug Partin was president between Big Daddy and Keith, and James Hoffa Junior is the current international president.) Kieth sent Craig to Aunt Janice, and she sent him to me. Not many of us are left alive who knew Big Daddy, and Craig wanted to get as close to the source as he could.

When Craig asked me what the traits were that led Big Daddy to being so easily trusted, I couldn’t answer concisely. Craig and I chatted a few times, and I was lost for an answer other than to say that you had to be in a room with him to understand his charm. As Hoffa said, he could charm a snake off a rock. He fooled Mamma Jean, I said, and she was one of the sharpest people I ever knew. I couldn’t explain it more than that.

The Irishman was a whopping 3 hours and 29 minutes long, even after massive edits and major simplifications. Al Pacino, Robert DeNero, Joe Pesci, Ray Ramona, and all the big names drew big crowds to packed theaters. Craig’s role was edited down to five minutes, less time than a high school wrestling match, but a lot of details can be hidden in brief moments. To portray what type of person would stand up in a room full of Hoffa’s bodyguards and mafia hitmen and point a finger at Hoffa, Scorcese changed the camera angle to make Big Eddie loom large over everyone in the room. Craig did a good job. Scorcese gave him all 20 minutes to use for future auditions; if you’re a producer with $257 Million, please call Craig Vincent.

Covid shuttered theaters in early 2020, and Netflix picked up rights to The Irishman. It set global streaming records. Like billions of people, I sheltered in place and worked on a project I had postponed until I felt I had time to focus. As I distilled the mountain of information into a manageable mound, I realized that Big Daddy’s testimony continues to shape history, and I wanted to share his story.

I’m Jason I. Partin, former co-captain of the Belaire Bengal wrestling team. Like James R. Hoffa, I sign legal documents using my middle initial, but I pronounce my name Jason Ian Partin (in Louisiana, it’s ee-ann). Like Jimmy, I answer to any one of my nicknames: Magik, JP, Jase, J, or Dolly (with a last name of Partin and seven years of two-week to six-month deployments on diverse teams with strict radio discipline against using real names, it was inevitable that I was always nicknamed after the charismatic country singer Dolly Parton, payback for all of the jokes about Hillary and a Boy Named Sue.)

The internet has a gaggle of Jason Partin’s, including my cousin, Jason Partin, a Baton Rouge physical therapist Joe Partin’s grandson (he played football for the Zachary Broncos while I wrestled for the Bengals). But there’s only one jasonpartin.com; another url of mine, LSUmagic.com redirects there. My website currently says I’m a close-up magician who frequently performs at Hollywood’s Magic Castle (only the member’s rooms so far), and that I’m some type of engineer and consultant. People who know me well say I have Big Daddy’s smile, though not a smidgen of his charm. I lost my Louisiana accent decades ago.

My Linkedin profile adds things like my medical device patents, documents with puns built in, like “Active Compression Technology to facilitate healing of broken bones,” small implants that use tiny Nitinol springs to pull broken bones together with a focus on hands and feet, with ACT now! written in the patent application; a pyrolitic carbon wrist-resurfacing implant with a fin to stabilize it in the radial bone (it looks remarkably like a San Diego “fish” style surfboard and is dubbed The Fish); a hydrogel spine nucleus implant that rehydrates diurnally, compressing in the day and swelling at night, like a healthy nucleus does (I ran out of jokes for that one); and a handful more under Jason Partin, Jason I. Partin, and Jason Ian Partin, depending on whims of attorneys and patent agents.

I’m listed as a co-author on a couple of ASTM spine fusion implant strength testing (each disc is about one square inch; balancing body weight, rucksacks, etc. leads to around 600 psi across a fusion implant), one in mixed-metal implant corrosion testing (certain types of stainless steel act like one half of a battery terminal when near Nitinol inside the body), and a safety standard for wrestling mats (impact softening, durability, anti-microbial, etc.)

There’s more, but hopefully enough to get to the point and telling you about Big Daddy, what I couldn’t tell Craig Vincent before Covid, which will take a few more short stories. It’s bigger than you think.

For example, Hoffa vs The United States is a cornerstone of the 2001 Patriot Act. After 9/11, President George W. Bush Jr assigned assistant U.S. Attorney General and Harvard Law School Jack Goldsmith to justify monitoring the cell phones of all Americans without a warrant or probable cause; that would have been impossible Without Bobby Kennedy bending the 4th Amendment to get Hoffa, allowing lower courts to cite the 1966 supreme court decision.

The Patriot Act, officially called “The Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism – USA PATRIOT – Act of 2001,” which is even stickier when dummied down to The Patriot Act. It was used to imprison and, inadvertently torture, suspects behind 9/11 in Guantanamo Bay without a lawyer or a trial for more than 20 years; to this day, many are still there.

Not all things got worse after 1966. Some things have improved, especially to the common use of “Negro” used in the JFK and MLK Assassination Report, or how no one today would tolerate Big Daddy freed from rape charges by a jury of his peers because “ain’t no white man deserve to go o jail for nothing he did to a Negro girl.” I have not finished reading the MLK portion of the report, so I can’t comment. If you ask Hillary Clinton, I’m sure he’d have more to say about all of that than I would.

As for the second Gulf war that officially lasted more than twenty years – my generation’s Vietnam – and was based on President Bush Junior’s mistake that Saddam still harbored weapons of mass destruction, and for the hundreds of thousands of maimed soldiers returning home with PTSD, Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome, the hidden disease Audie Murphy died trying to end for all Americans, I could talk your ear off. Big Daddy didn’t kill Audie Murphy – I uncovered that before the internet showed the black box of his airplane – but with my background I think the least I could do for Audie is to continue his fight to help those who suffer long after a war officially ends. PTSD isn’t just for soldiers; every one of Big Daddy’s rape victims, kidnapped kids, beaten corporate mangers who refused Teamster Labor, and others all had PTSD without serving in the military, just like millions of Americans with their own stories to tell. In a way, I decided to share my story to help all Americans, however you define that.

I do not have a plan to help us move forward. (That’s not true, it’s just a long one, and we’re not ready to have that conversation yet.) American military special operations teams live and die based on the five paragraph operations order. In sequence, it is Situation, Mission, Execution, Service & Support, Command & Signal; we win when we focus on understanding the situation before forming a plan, to understand the tumor to be removed before beginning surgery, and then using lower paragraphs to methodically heal and move forward. To help us understand the situation that lingers since the 1960’s, I wrote a memoir to let you know what I knew then, and what I’ve gleamed thirty years and hundreds of books later. When the situation is clear, the mission is usually obvious to a team focused on not loosing anyone in battle.

But a memoir is based on memory, so anything I write is inherently flawed; that’s a problem with every witness in the conflicting JFK assassination report and the tsunami of books to come out since it was released, and by default everyone who has learned from a faulty foundation is biased and may be good people, but they are as mistken as Chief Justice Earl Warren in the Warren Report. I wrote what I believed to be true, and cited sources when I could.

As I used the internet to check facts and challenge my assumptions, I was shocked when I first read the Louisiana High School Athletic Association records on LHSAA.org; new evidence, to me at least, proved that Hillary Clinton didn’t break my finger, Hillary Moore did.

That hurt my brain at first. I was probably more shocked than you are right now. I called a bunch of old buddies and confirmed it. Of course they said, Hillary’s last name was Moore. A few reminded me of that throw – it really was gorgeous.

You’d think I’d recall Hillary’s last name because he beat me so badly, but wrestling is not like that. We shook hands before every match, and in front of a few fans and parents as representatives of each other’s teams in dual meets, but we never spoke. Not once. I can’t tell you what he sounded like. To me, he wasn’t anything more than A Boy Named Sue, an opponent stronger than Hercules, the first obstacle in a series of heroes journeys. I never focused on his name, and when other wrestlers mentioned him to me, they said something like: “Hey dude! I heard Hillary kicked your ass again.”

Maybe I remembered Hillary as Hillary Clinton because in late 1992, a few months before I first read the JFK Assassination Report, I took a break from practice with the Fort Bragg wrestling team to enter the 82nd’s pre-Ranger course. Only around 5,000 Rangers graduate from the Fort Benning course each a year, and a few come from Fort Bragg to test their metal. Competition is fierce to represent the All Americans among all other units. Of 269 paratroopers who began – ten shy of Audie Murphy’s kill count, and almost half of the Mai Lai massacre – only nine of us crossed the finish line. Of the nine, six of us wrestled of us in high school; two also in college.