Wrestling Hillary Clinton: A Memoir

But then came the killing shot that was to nail me to the cross.

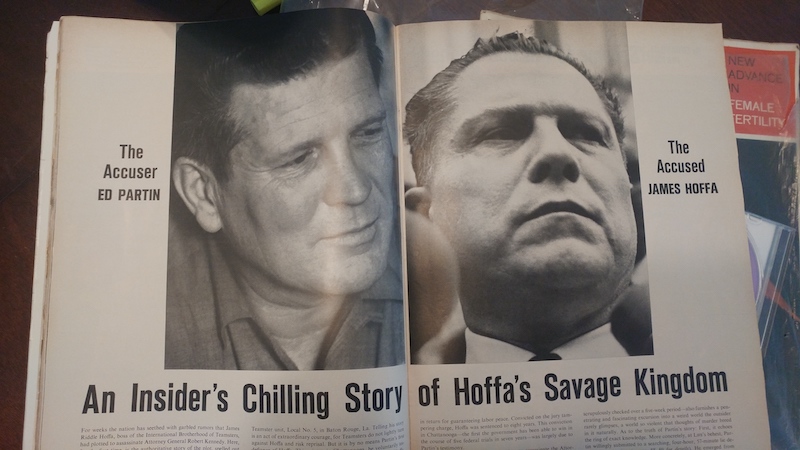

Edward Grady Partin.

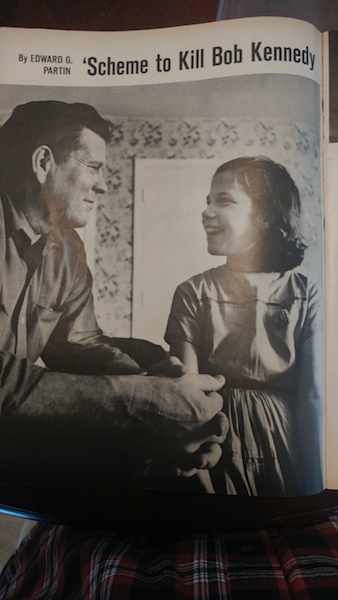

And Life magazine once again was Robert Kenedy’s tool. He figured that, at long last, he was going to dust my ass and he wanted to set the public up to see what a great man he was in getting Hoffa.

Life quoted Walter Sheridan, head of the Get-Hoffa Squad, that Partin was virtually the all-American boy even though he had been in jail “because of a minor domestic problem.”

– Jimmy Hoffa in “Hoffa: The Real Story,” 19751

As of 31 December 2024, this is mostly true.

I’m Jason Partin. Thirty four years ago, Hillary Clinton pinned me in the second round of the 145-pound finals match of the Baton Rouge city high school wrestling tournament. I almost won in the first round, but Hillary escaped my cradle by kicking his leg so hard that he broke my left ring finger, just below the middle knuckle; it healed awkwardly, and to this day my fingers split like Dr. Spock’s “live long and prosper” salute in Star Trek.

The joke about Hillary was that he was like Johnny Cash’s song “A Boy Named Sue,” a kid who grew up tough and mean because of his name, and that like Sue, Hillary “kicked like a mule, and bit like a crocodile.” Hillary had never bit anyone, but he sure could kick hard. No one had broken my craddle in almost a year; I had 36 pins that season, and most were from the craddle. It’s not a move Coach used himself, probably because he had stubby arms and couldn’t reach around an opponents head and leg at the same time, but he showed me how utilize my relatively large hands and lanky arms, to clasp with my thumbs tucked (“A wrestler looses 15% of his strength if he thumb if out,” he said), and to calmly move my hands away, letting my elbows come together like the mechanism of a bolt cutter with less strength; he never explained why, but the first time I tried it I had no doubt. Based on his old-school advice, when I rode around with him the summer before, delivering wrestling supplies to rural schools in southern Louisiana’s Cajun country, I carried a Baton Rouge Advocate newspaper and slowly crumpled one sheet at a time into tight balls, alternating each hand until the floorboard was a pile of tightly wadded paper balls. Bulky Sunday papers were brutal. But it worked, and the craddle became my signature move. With my hands strengthened by small forest worth of newspapers, and an autumn of training in the football team’s weight room, where Coach was assistant coach and could us access, I clawed my way into the Baton Rouge city tournament finals and I almost defeated Hillary Clinton, the undefeated three-time returning state champion at 145 pounds.

He kicked and he kicked again, and then he kicked some more. He grunted and growled like an animal fighting to escape a steel-spring trap again with teeth dug into its leg. He kicked with the exact frequency of a MK-19 automatic grenade launcher, 48 rounds a minute, but with much more force than the kickback of. MK-19, even when loaded with the longer high-explosive dual-purpose rounds used a year later in the first Gulf war; it could shake a heavy Humvee full of paratroopers, but it was nothing compared to the brute force of Hillary Clinton, captain of the Capital High Lions. I felt my grip weakening and victory slipping away more than I felt pain, though I’m sure hurt like hell. He broke free, stood up, and turned to face me with the speed I had grown to respect. He received a point for escaping. We were face to face again, his strongest position. He looked pissed. I had never seen him angry before, and I only had the smallest fraction of a second to realize that before the buzzer sounded. The referee pointed us to our corners. I had lost my chance. When someone’s angry, they make mistakes.

Jeremy, our 142 pounder and co-captain of the Belaire Bengals, handed me a fresh hand towel. I wiped the sweat from my eyes, and dried my hands; I saw, but did not focus on, my rapidly swelling knuckle. Coach asked, and I said I was fine. I wanted us to face off while Hillary was still riled. Coach nodded and stepped back.

I watched Hillary’s coach, a spherical mountain of an African American man who had never wrestled, yet had coached the fierce Capital Lions for as many years as Coach had coached the Belaire Bengals, calmly telling Hillary to relax. Hillary nodded. Another Lion whom I don’t recall. The Lions were all African American, an artifact of caucasian families moving away from the downtown capital building in the 60’s and 70’s, and they all covered their heads with dark maroon hoodies that made them seem, from across the mat, like a angled of Russian Matryoshka dolls stretching from 103 pounds up to 275, the maximum for heavyweights back then. The smaller Lion tried to keep pace with Hillary’s shaking arms and dancing legs. I watched Hillary’s Lion’s coach, trying to decipher his hand gestures. Hillary nodded at each one. Coach and Jeremy let me be. Seconds later, I trotted back to the center of the mat. Hillary had chosen neutral, and we each put one foot forward and faced off.

I focused on Hillary’s hips. Coach only gave a handful of nuggets of wrestling advice in the three years I had known him, and one was to watch an opponents hips, not their eyes or hands, because where their hips went they went. That was advice from his Iowa coach before he left as an alternate on the olympic team, at a time in history when Russians were dominating the sport because they focused on taking an opponent off their feet with bear-hug throws, like Hercules defeating Antaeus by holding him above Mother Earth, his source of strength.

“But to do that,” Coach told us, “they need to get their hips close to yours. Get you to overreach, so they can step in close. The Russians realized that if you break a man’s stance, you can do what you want to him. Don’t break your stance.” He got into his stance, which he compared to holding a shovel so you could dig heavy dirt on a farm all day without fatiguing or hurting your back; legs bent and thighs strong, so that fatigue never leads you to break your stance. “Vince Lambarti said that fatigue will make a coward out of anyone,” Coach told us.

Armed with that knowledge, I got into stance and focused on Hillary’s hips. He was calm and dangerous. He wouldn’t let me get a low single again. From my periphery, I watched the referee’s chest and face for telltale signs of inhaling and tensing to exhale; his hand was poised above his head.

Another piece of advice was to just wrestle. No matter what had happened the previous round or that morning or the weekend before, just wrestle. With everything you have left in you, just wrestle. It was related to unsolicited advice he received from a gold-medal olympian, the most celebrated of a generation and second only to Iowa’s Dan Gable, a man who made international news by pinning all four opponents in the 1960 olympics, but had barely beaten Coach 4:3 in trials. Before Coach’s next match for third place, held only minutes after his loss in semi-finals and back when rounds were three minutes each, that wrestler approached Coach and said, “Someone will win. It might as well be you.”

Just wrestle. Someone will win. For the next two minutes, it doesn’t mater who. Wrestle.

The ref blew his whistle and dropped his hand and we wrestled. Hillary shot a double and I sprawled, and I sprawled again and again. I kicked both feet into the air and thrust my chest onto Hillary’s head and back, and I kept my arms tucked tightly on either side of him, and eventually Hillary’s head creeped lower and his arms extended and he was off his stance. It was then that I crossfaced the hell out of him with the force of God. His head turned and his grip broke, but before I could spin behind him, he leaped backwards and towards the edge of the mat and sprung back into his stance.

We kept eye contact and crab-walked towards the center, a truce-of-sorts wrestlers fall into without ever discussing it. We were almost to the center, but the truce was loosely defined, and Hillary’s forearm shot to my neck with the speed of a rattlesnake seeking prey. He yanked as hard as he kicked.

“Don’t be a headhunter,” was another piece of advice from Coach. I took advantage of my forward momentum and Hillary’s arm raised to my neck, and I shot a high single and took him to the mat; but, he sprung up and turned to face me so quickly that no points were scored for either a takedown or an escape. For the briefest of moments, we stood face to face again, and then I was surprised to be in a bear hug.

He caught it on my exhale, already out of breath, and threw me in a beautiful, perfect throw that would have earned him the full five points in summer freestyle. I watched the ceiling appear in my view, and in slow motion I watched my frayed size 12 Asics Tiger wrestling shoes arc through the air; temporarily blocking the basketball scoreboard with a timer made of dozens of small florescent lightbulbs that spelled out our names and the schools we represented. I watched my feet pass the faces of a few hundred fans who paid to see finals and filled Baton Rouge High’s gymnasium; whether true or not, in my mind today I see the looks on hundreds of faces, most in awe, and more than a few cringing at the inevitable. It really was a beautiful throw.

Hillary brought my shoulders to the mat with thud that shook the bleachers as if a C-130 Hercules had dropped a 15,000 pound bomb in the gymnasium. Yes, that’s exactly what it felt like. I felt the shock wave of Hillary’s throw when I hit the mat, and I felt it reverberate back and forth between us and the bleachers. Had I wind in me, it would have bellowed out. I almost blacked out from the shock wave.

I bridged. I planted the soles of my Asics flat on the rubber mat and pushed, I looked to the sky and used a year’s wroth of neck muscle training to keep my shoulders off the mat. Hillary kept squeezing my chest like a boa constricter slowly killing it’s prey. He was on his toes, adding all his weight to my chest, fighting against my fatiguing neck muscles with everything he had. Without air but with everything else in me, I bridged, but my bridge began to collapse. I stared at the timer, upside down then but somehow right side up in my mind today. Part of just wrestling is knowing things like how many seconds are left, because it changes your strategy. I had a choice: try to force my knobby knuckles between our bodies, irritating his ribs and giving me an inch to push my arm through and punch through to the other side, but taking a lot of energy and therefore oxygen; or, focus on bridging and holding out until the buzzer sounds. I had almost a minute left.

I focused on trying \ to knuckle though Hillary with my right hand, but he only constricted more and my bridge slipped a bit so I focused on that instead. I stared at the clock, and couldn’t help but notice that over their team hoodies, the former all-Louisiana team wore matching shirts from last summer’s camp, a simple white t-shirt with plain black letters; only Chris Forest, Baton Rouge High’s heavyweight, wasn’t, because he couldn’t fit into an XXL, but he stood by his 136 team captain, Clodi, who’s minister dad had found the shirts for them in a Christian supplies store under the LSU I-110 overpass. For us, the words of Ephsians 6:12 rose above religious beliefs. The shirts said: “For we wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places.”

I bridged and I watched and I hoped, but I was out of air and Hillary was a beast. My spirit was trying, but flesh was fatigued. Sometimes hope isn’t enough, and I felt the tiny bumps of my back acne touch, then I saw the ref slide beside us and put his cheek against the mat by my shoulders. He blew his whistle and slapped the mat, and it was over. We stood up, and he raised Hillary’s hand. The applause and stampeding of feet on the bleachers was louder than the bomb that had gone off earlier. It really was a beautiful throw.

I walked to Belaire’s corner. Coach stuck out his right hand and held mine. His other stubby but ridiculously strong hand clasped my left tricep. He looked up into my eyes, his short but strong stance unbroken, and said, “Good job, Magik.” I nodded. He had shook my hand the same way, and said words to the same effect, almost 152 times over three years, only missing a few matches at big tournaments when six to eight mats were out and multiple wresters were on deck at once. Only the person on the mat knows what was happening, and never once did Coach discuss the past unless it was useful for the match about to happen.

Jeremy, a man of few words, stood up and offered me the captain’s chair next to Coach. Surprised, I sat down and accepted the fresh towel. He stepped behind us, in the corner that was now empty, the guys wandering off to watch another match. Coach and I remained. Another Belaire wrestler was on deck. I had a job to do, and nothing else mattered for the next six minutes.

Later, I overheard Pat, a former heavyweight and Baton Rouge High’s assistant coach, laughed and told Jeremey and Coach about how Hillary held me so hard the only thing I could wiggle were my eyeballs (I wouldn’t argue that). His smile went away, and he asked Coach what happened, that I had been focused all spring but seemed lackluster that day and he wanted to know if I was okay. Coach simply replied that I had a lot on my mind, because my grandfather was sick. He waddled away to sign a score sheet, and everyone nodded. They had seen the news.

Hillary was a beast, but I almost defeated him. Forty years later, I’m still proud of that. To a 17 year old kid and high school senior, almost defeating Hillary Clinton in the Baton Rouge city tournament was bigger news than when my grandfather died a few weeks later.

I attended my grandfather’s funeral on 16 March 1990 wearing a blue and orange letterman jacket with a chest full of gold safety pins, one for every pin that year, grouped in clusters of five for easy counting, with one pin on the jacket and four dangling below it. My left ring finger was buddy-taped to the middle finger, though by then it was more like a badge of pride than needing more time to heal; for the occasion, I applied two fresh strips of cloth tape, bright white and not grey and frayed like they usually were. Someone was bound to ask, and I had a great story to tell. My face shone from lingering pride at media coverage, and a small award from Coach and the team that they presented in front of all 380 Belaire seniors. I was unimpressed by the crowds that choked traffic around Green Oaks funeral home.

Besides the Patin family, the former Baton Rouge mayor was there, and so was the entire Baton Rouge police department, reporters from every major newspaper, a hell of a lot of huge Teamsters, a gaggle of FBI agents, and Walter Sheridan, former director of the FBI’s Get Hoffa task force and a respected NBC news correspondent in the 1980’s, and a surprisingly long lineup of middle aged brutes from the 1954 LSU football national champion team. Billy Pappas, our first Heismann trophy winner, who went on to play for the Houston Oilers and become, of all things, a dentist, was a hometown celebrity and one of the pallbearers, which was part of what drew crowds to the funeral. Secretly, I hoped a few old teachers and classmates from when I was a runt in middle school would see they’d see me with them, if only to ask about my letterman jacket. But no one commented on my chest full of pins or the silver medal from city finals, probably because no one knew about Hillary Clinton back then. Reporters simply listed me as one of five surviving grandchildren,. Only Walter asked about my buddy-taped fingers; he noticed details, and was he good at his job. Bobby Kennedy had hand-picked him to rejoin the force after Walter had helped his brother’s campaign for presidency in 1961; when President Kennedy won, he appointed his little brother to head America’s justice system.

Most people were focused on my grandfather and his final words. He was Edward Grady Partin Senior, the Baton Rouge Teamster leader famous for testifying against International Brotherhood of Teamsters president Jimmy Hoffa and sending him to prison.2 He was nationally famous, having been portrayed by the rugged and classically handsome actor Brian Dennehy in 1983’s Blood Feud, the one where Robert Blake won an academy award for “channeling Hoffa’s rage,” and some daytime soap opera heartthrob portrayed Bobby Kennedy without winning anything for it.

We called my grandfather Big Daddy, and all of Baton Rouge looked up to him. Half of the city attended his funeral, and the spectacle made front-page news across the nation. After the funeral, when most people got up and flocked around Billy and the LSU players, I leaned over and told Walter that Edward Partin’s final words were: “No one will ever know my part in history.” He agreed that it sounded funny when said out loud, and that Big Daddy was probably right.

Walter’s words stuck with me, and for the next thirty years, whenever I had a break time between the rounds of life, I investigated the meaning behind Big Daddy’s final words, and pondered his role in killing President Kennedy. This is his story, according to what I know so far.

In 1924, Big Daddy was born in Woodville, Mississippi, to Grady and Bessie Partin. Great-grandpa Grady was a lush who ran out on them during the Great Depression, and my eventual grandfather began providing for Grandma Foster (Bessie later remarried) and his two little brothers, Doug and Joe, men I’d eventually know to be as big as Big Daddy. In 1943, a 17 year old Ed Partin and a 12 year old Doug stole all of the guns in Woodville, and them to crime bosses in New Orleans, two hours downriver from Woodville. They bought motorcycles and had what Doug says were the best few weeks of his childhood, but were arrested by the Woodville sheriff later that summer.

Doug was set free because he was a minor, but the judge gave Ed a choice: join the marines or go to jail. He joined, punched his commanding officer in the face, and became a dishonorably discharged marine within two weeks of the judge’s decision. He returned to Woodville a free man, turned 18, and with all young men away in the war and his brute size, he easily took over the Woodville sawmill union. Soon he also ran the teamsters who drove horse wagons to and from the sawmill. After the war, when trucks and gas were in supply again, he also ran the trucker’s union in and out of southern Mississippi. He was ruthless and effective, and in the 1950’s, he and his young wife, my Mamma Jean, moved to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and Big Daddy began to run Teamsters Local #5 under International Teamster President Jimmy Hoffa, who admired his style and told everyone to trust him.

By the early 1960’s, after President Kennedy’s embargo had all-but strangled trade with Cuba, Big Daddy was meeting with Fidel Castro and shipping arms and boats from New Orleans to Cuba; allegedly, before Kennedy’s failed Bay of Pigs Invasion Big Daddy also trained Castro’s generals and a handful of what would have been their special ops soldiers. FBI director J. Edgar Hoover became interested and assigned the New Orleans FBI office to monitor him, and Hoover’s records in the JFK Assassination Report show that in 1962 Edward Grady Partin and Jimmy Hoffa plotted to kill the president’s little brother, Harvard graduate and U.S. Attorney General Bobby Kennedy, by either tossing plastic explosives Big Daddy could get from either Castro or New Orleans mafia boss Carlos Marcello into Bobby’s family home, killing him and potentially his wife and children; alternatively, because Big Daddy was adverse to killing kids, Hoffa said they could recruit a sniper with a high powered rifle outfitted with a scope to shoot Bobby as he rode through a southern town in one of the convertibles “that spoiled snot-nosed brat Booby” likes to ride around in and show off. Hoffa had been calling Bobby “Booby” and “spoiled snot-nosed brat” in public for many years, ridiculing his Harvard law degree without experience, and the nepotism of President Kennedy appointing his little brother to the highest legal role in America. At one point in a news conference, Hoffa lunged at Bobby to prove who was the bigger man. If they used a sniper to kill Bobby, Hoffa allegedly said, they’d have to ensure he couldn’t be traced to the Teamsters.

A few months later, Big Daddy helped 23 year old Baton Rouge Teamster Sydney Simpson kidnap his two young children after he lost them in divorce court. (Though he was averse to killing kids, my grandfather seemed okay with kidnapping them; that was the “minor domestic problem” Jimmy Hoffa quipped about for the next ten years.) Sydney and Big Daddy were arrested and put in a Baton Rogue jail. Coincidentally, later that day, Big Daddy was also charged with manslaughter in Mississippi, saving Mississippi police from searching for him. Word got out, other charges began to roll in. Big Daddy faced life in prison.

He told Sydney, “I know a way to get out of here. They want Hoffa more than they want me,” and when Sydney asked what if he knew enough to help the FBI get Hoffa, Big Daddy replied, “It doesn’t make any difference. If I don’t know it, I can fix it up,” and said, “I’m thinking about myself. Aren’t you thinking about yourself? I don’t give a damn about Hoffa. . . .'” Big Daddy made a phone call, and a few days later Bobby Kennedy had him sprung from jail. (Poor Sydney remained and went to prison, but his words were recorded by attorneys for posterity to ponder.3) Through Walter, Bobby offered Big Daddy immunity if he would infiltrate Hoffa’s inner circle, and find “something” or “anything” to remove Hoffa from power.

Bobby acted out of desperation. He and J. Edgar Hoover had spent untold taxpayer money supporting 500 agents on their Get Hoffa task force for almost ten years. Journalists called their Blood Feud the longest, most expensive, and fruitless pursuit of one man in any government’s history, and Bobby had a black eye in the face of his big brother. He probably would make a deal with the devil to get Hoffa. Big Daddy accepted the offer, called Hoffa to set up a meeting, and began telling Walter everything he saw and heard behind closed doors. As Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote, Edward Partin became the equivalent of a walking bugging device. For the next two years, the Get Hoffa Task Force revolved around Big Daddy and what he told Walter.

On 22 November 1963, a few months after Big Daddy made his deal with Bobby, President John F. Kennedy was shot and killed by at least one gunman as he rode through downtown Dallas in his open convertible with the Texas governor and his wife. Less than an hour later, New Orleans native and Castro sympathizer Lee Harvey Oswald, a former marine who trained in the Baton Rouge civil air force under the alias Harvey Lee, was arrested for shooting and killing Dallas police officer J.D. Tippit with a bulky .38 revolver outside of a movie theater a few blocks from where Kennedy was shot. Oswald was arrested, and police immediately charged him with killing both Tippit and President Kennedy. Oswald’s words, spoken before being read his Miranda Rights, were: “I am only a patsy!” He was escorted to jail, and FBI and Dallas police looked where he worked, the 6th floor of a downtown book repository overlooking where Kennedy was shot, and they found Oswald’s 6.5mm Italian army surplus carbine, modified by a Dallas gunsmith to include a high-powered scope.

Hoffa, upon hearing the news of Kennedy’s death and Oswald’s arrest, told his entourage in Florida, “Bobby’s just another lawyer now.” He ordered all Teamster halls to keep American flags at full mast.

Officer Tippet’s murder was overshadowed by President Kennedy’s, but Dallas knew that they lost Tippet, too. He was a respected officer, a WWII soldier who won the bronze star and had a family at home. Police had to protect Oswald from vengeance, and he was heavily guarded while he awaited trial. But two days after being arrested, Oswald escorted out of the Dallas police station in handcuffs and on international live television, and Jack Ruby – a Dallas nightclub owner, air force veteran, low level mafia runner, and associate of Hoffa and my grandfather – walked through the police station, past a few dozen armed police officers, and slid a Colt .38 “detective’s special” handgun from his trenchcoat pocket, and shot Oswald in the stomach point-blank.

A Pulitzer-prize winning journalist photo of the shot showed Oswald doubled over in pain, and Ruby’s middle finger on the trigger, a mafia technique for close-up kills. (In theory, when shooting from the hip with a stubby gun, you’re more accurate if you point your trigger finger along the barrel and pull the trigger with your middle finger; killers say it’s the ultimate Fuck You.) A few hours later, Oswald was pronounced dead in the same hospital that had held President Kennedy’s body and the wounded Texas governor, and where police had found another 6.5mm round, like the ones in Oswald’s room of the repository, inexplicably lying on a gurney beside the governor. Jack Ruby was arrested and would be found guilty in a court of law; it was the first time someone was shot on live television, and dozens of millions of witnesses had no doubt of Ruby’s guilt, but most suspected a conspiracy involving, at the least, Lee Harvey Oswald, who couldn’t stand trial from his grave.

Vice President Lyndon Johnson became president, and asked Chief Justice Earl Warren to oversee a committee digging into possibly conspiracies to kill President Kennedy. Ten months later, the hastily assembled 1964 Warren Report was released. It mistakenly concluded that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone when he shot and killed President Kennedy, and that Jack Ruby acted alone when he shot and killed Oswald. A second, longer study was planned behind the scenes; it would become the 1979 JFK Assassination Report, but for some reason it was kept classified, and the government’s official verdict for a man who never stood trial adhered to the 1964 Warren Report.

Around the same time the Warren Report was released to public scorn – few believed one man could do so much damage, especially one with abysmal military marksmanship records – Jimmy Hoffa’s jury tampering trial was being overseen in a small courtroom in Chatanooga, Tennesee, by Bobby and Walter and a team of federal agents reporting to Hoover. It was the Test Fleet case, a charge of jury tampering in 1962, soon after Big Daddy was sprung from jail, and in he was in Hoffa’s corner of the courtroom. When he stood up as the surprise witness, Hoffa’s otherwise stoic and calculating face went pale. He exclaimed “Oh God! It’s Partin!” in front of the jury, probably sealing his fate before Big Daddy gave his testimony. Big Daddy smiled and, in a calm southern drawl, told the jury that Hoffa suggested he bribe a juror by tapping his back pocket and implying that $20,000 “should do it.” There was no other evidence. A few days later, the jurors deliberated less than four hours and found Jimmy Hoffa guilty of jury tampering. The judge sentenced Hoffa to eight years in federal prison based solely on Big Daddy’s word.4

At Hoffa’s trial, Hoover announced that he’d assign extra federal marshals to protect the Partin family from inevitable retribution. He then released parts of FBI records to Life magazine, and told media that Big Daddy thwarted a plot by Hoffa to bomb Bobby’s home using plastic explosives. Edward Grady Partin was dubbed an all-American hero, and Big Daddy and Mamma Jean’s five children, my dad (Edward Grady Partin Junior), Janice, Keith, Cynthia, and Theresa were showcased alongside the Johnson family, by then known as the first-family of America’s new president. (Mamma Jean’s absence from photos and quotes wasn’t discussed.) To America, the star witness against Jimmy Hoffa was a trustworthy family man who risked the lives of his children to steer America in the right direction by standing up to corrupt unions and the newly recognized organized crime syndicate. Big Daddy returned to running Local #5 with federal immunity and a squad of federal marshals following my family wherever they went: part of the deal with Big Daddy was that his kids be protected.

Over the next two years, Hoffa’s army of attorney’s attacked Ed Partin’s credibility in national media, claiming he was a Castro sympathizer, rapist, murderer, dope fiend, and thief; but no one could find records of all his crimes. It wasn’t a lack of resources. Hoffa had $1.1 Billion in untraceable cash from monthly dues of 2.7 million Teamsters – a ridiculous sum in 1950’s money – that he had skimmed to lend money to mafia families so they could to build casinos and hotels if they hired Teamster truckers to haul building materials, guns, and a slew of things; and to Hollywood producers so they could make films that used Teamster trucks to haul equipment and trailers to house actors. Hoffa had a bottomless stash of money, almost 3 million fiercely loyal Teamsters, and the best lawyers money could buy. Frank Ragano, now known as a “lawyer for the mob,” had only had two clients other than Jimmy Hoffa, New Orleans mafia boss Carlos Marcello, and Miami mafia boss and Cuban exile Santos Trafficante Junior, men known for their ruthless tactics and debts to Hoffa (Marcello alone owned $21 Million from money he borrowed to build New Orleans hotels), and Hoffa used his lawyer’s contacts and everything in his power to discredit Big Daddy or intimidate him into recanting his testimony, men like Frank “The Irishman” Sheeran, a combat veteran, Teamster leader, and mafia hitman all in one. They began to spread word that all mafia debt – around $121 Million – would be forgiven if “someone” could do “something” to get Edward Grady Partin to change his testimony, or to have Hoffa’s case thrown out because Bobby Kennedy violated the fourth amendment in his zest to get Hoffa.

They failed, despite the unambiguity of the single-sentence fourth amendment. It was hand-written by our founding fathers in 1789 to protect Americans from a police-state, and it says: “The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.” They argued that Bobby violated the second amendment by sending Big Daddy into Hoffa’s camp to find “something” or “anything” against Hoffa, but Chief Justice Earl Warren was the only one of nine justices to dissent. Big Daddy’s testimony was upheld, and Hoffa vs The United States forever weakened American freedom because of the word of one “all-American hero,” and from then until today, prosecuting teams would point to Hoffa vs The United States, lower courts would uphold the fourth amendment’s new interpretation, and prosecutors know that and continue to push the limits of the fourth amendment and Hoffa vs. The United States.

Hoffa began his prison sentence in 1966 – up to eleven years by then – and spent six days a week for six years pounding prison mattresses in his prison work detail, pondering things and writing his memoirs. He was pardoned by President Nixon in October of 1971, and Jimmy Hoffa was a free man until he famously vanished from a Detroit parking lot on 30 July 1975.

In 1979, behind closed doors, the U.S. congressional committee on assassinations completed the JFK and Martin Luther King Junior Assassination Report. For reasons I don’t know, President Carter kept it classified, and so did Presidents Bush Sr. and Reagan. President Bill Clinton released the first part in 1992, but only after 10 million people saw Oliver Stone’s film, JFK – based on New Orleans district attorney’s memoir, “On the Trail of Assassins” – and demanded that the report be made public. It reversed The Warren Report, and said that, though they didn’t have proof and therefore it’s inconclusive, the three leading suspects with the means and motivation to kill President Kennedy were Jimmy Hoffa, New Orleans mafia boss Carlos Marcello, and Miami mafia boss and Cuban exile Santos Trafficante Junior.

A deluge of books and films flowed following the1992 partial release of the JFK Assassination Report, and that beheamtih said almost everything I’ve summarized so far. Coincidentally, at the time, I was on President Clinton’s quick-reaction team, a paratrooper on the 82nd Airborne – ironically called the All Americans – with a chest full of medals that would have impressed even the 17 year old kid that had been me. In the 90’s and early 2000’s, a slew of books and television specials began to accumulate. Most were crap, written by partially informed people who may have hoped for a lucrative movie deal and inadvertently clouded the pool of facts with speculation and hyperbole.

I’ve paid attention to media every time more of the JFK Assassination Report trickled out, after presidnts Bush Jr., Obama, and Trump, Biden and then Trump again released more of the report. The drip slowed but continued to leak for thirty years, yet without closure of who killed Kennedy and why. Nor has anyone explained why presidents since Jimmy Carter have kept so many things secret about the report; a president should be motivated to share everything they knew about how to stop people from killing presidents.

In the summer of 2019, film producing legend Martin Scorcese had spent around $257 Million to make and market his opus about Hoffa’s demise, “The Irishman,” based on a 2004 memoir by Frank “The Irishman” Sheeran, “I Heard You Paint Houses.” Frank claimed to have painted the wall of a Detroit suburb home red with Hoffa’s splattered blood. He knew Big Daddy well, and mentions him throughout the book; for that, and because Hoffa’s prison sentence had to mentioned, my grandfather had a small part in The Irishmen to help move the plot along; Scorceses himself said he was making entertainment, not a documentary, and his job was to sell tickets.

The Irishman was a whopping 3 hours and 29 minutes long. The burly actor Craig Vincent’s portrayal of “Big Eddie Partin” was edited down to five minutes, less time than a high school wrestling match. But he took his role to heart. Craig spoke with our family to research his role, calling Keith Partin, current Teamster Local #5 president after Doug Partin retired twenty years before, and Craig found Janice on a website of Partin genealogy.

When Craig asked me what the traits were that led Big Daddy to being so easily trusted, I couldn’t answer concisely. We chatted a few times, and I was lost for an answer other than to say you had to know him, and that there are few of us left alive. I admitted that most people had long forgotten who Ed Partin was. Craig, who is a few years older than I am, didn’t recall seeing 1983’s Blood Feud, or reading the incessant news and public debate about Big Daddy and Hoffa in the 60’s and 70’s. Had he not been researching Big Daddy’s role, he would never have thought to ask that question. Craig’s interest sparked my thought: why was the case still open? And, if Martin Scorcese couldn’t create a character based on Big Daddy’s aura, who could? I still don’t know.

Scorcese’s film opened in theaters with critical acclaim and box office success, but Covid shuttered theaters and Netflix picked up rights to The Irishman, which set global streaming records, but shifted priorities away from solving old crimes. It was a remarkable two years in humanity that we have yet to understand and simplify; given that we’re still trying to understand Kennedy’s death sixty years later, I probably won’t live to see the long-term effects of Covid. Like billions of people, I sheltered in place and worked on a project. I begin coaxing aging and dying memories from the nooks of my brain with time and persistence and not a lot else to do. As I distilled the mountain of information into a manageable mound, a new perspective began to take shape. I realized that wanted to share the bigger picture with a larger audience, but it would be more ambiguous than Hollywood’s desire for a simple solutions, so I put pen to paper.

This website is that Covid project, aged a few years.

I’m Jason I. Partin, former co-captain of the Belaire Bengal Wrestling team (like James R. Hoffa, I sign legal documents using my middle initial, but I pronounce my name Jason Ian Partin, and answer to any one of my nicknames, Magik, JP, Jase, or J). The internet has a gaggle of Jason Partin’s, including my cousin, Jason Partin, a Baton Rouge physical therapist Joe Partin’s grandson (he played football at Zachary while I wrestled at Belaire). But there’s only one jasonpartin.com (another url of mine, LSUmagic.com redirects there). The only social media I use is Linkedin, and it says I’m a combat vet of the first Gulf War, former unarmed peacekeeper in the Middle East, some sort of engineer or faculty, and a part-time magician who frequents Hollywood’s Magic Castle. I can’t provide facts any more useful to you than I already have, but I can write a memoir about my perspective of a man whose footprint continues to shape our world.

This isn’t just about killing President Kennedy. It’s about why, and it’s about freedom and what it means to be an American, at least from my perspective, and that’s heavily influenced by Big Daddy, Walter, Hoffa, Bobby, J. Edgar Hoover, and my experiences since leaving Louisiana and joining the army in 1990. One of the most obvious media, and it’s impact on public opinion. Thomas Jefferson said he’d rather have a free press than anything else, and Hitler said if I control the media I control the people; free media must be truthful, and what Bobby did to Hoffa using his connections at Life magazine, the most widely read and trusted media of that generation, was against the values and morals and ethics and laws he swore to uphold as a fresh Harvard law school graduate thrust into America’s highest role overseeing our justice system. Today, words like fake news and media influence from foreign nations is taken for granted; to preserve democracy of an truthfully informed public, we need to address truthfulness in media that’s continuously updated as new facts emerge and shine light on patterns we can use. I don’t know how, I just know it’s important, because I’ve seen the consequences of media bias. I don’t know if media or Bobby or Hoover influenced the supreme court, but truth in media and fairness in our justice system are linked. I’m sure James R. Hoffa would have more to say about that than I do.

We could start with Hoffa vs. The United States, and the ripple effects that reverberate in our daily lives without people realizing when and where ground zero began. When Bobby Kennedy bent the fourth amendment to get Hoffa, our Bill of Rights lost the power to protect people from unlawful search and seizure. To this day, we feel the effects.

Of the many examples, perhaps the most poignant is after the terrorists attacks flew airplanes into New York’s twin towers and Washington’s pentagon, when President George W. Bush Jr’s legal team used Hoffa vs. The United States as a cornerstone to build the Patriot Act, officially known as “The Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism – USA PATRIOT – Act of 2001.” That brilliant acronym overshadowed how was used to monitor hundreds of millions of Americans’s cell phones without a warrant, and it paved the way for torturing Guantanamo Bay prisoners held for what has now been decades without a lawyer or trial. According to some people, American rights only exist on American soil, and even then the foundation is shaky. It seems if we wanted to strengthen it, we could start by reassessing a cornerstone of the Patriot Act, Hoffa vs. The United States, and seeing what removing it for repair would do to everything else.

My grandfather’s word is a part in the Patriot Act, if only because he helped Bobby Kennedy bend the second amendment. Many other people are shouting for us to hear. In 2019, exactly when The Irishman was selling dozens of millions of tickets, a book by Jack Goldflake, a Harvard Law professor and former assistant US Attorney General who reported to President George W. Bush and led the legal justification Patriot Act, sold around a million copies saying what I just said. He justified the law, but questioned it’s justice, and became yet another voice in the loud crowded party of democracy. I can’t speak to law like he can, but I remember people who shaped our current world, and I’m probably the world’s last living expert on them.

I don’t know what would happen if it turns out that Big Daddy lied, or that the supreme court was wrong. Would Jimmy Hoffa get those years of his life back? Could the government un-hear what it monitored after Hoffa vs The United States? The concept applies to other court cases, and any policy built on a faulty foundation. When do you repair the foundation, and at what cost? To plan for the remodel requires understanding the past upon which assumptions are based. That’s where I hope this memoir helps all Americians, and by default, democracy and all humans on Earth.

A memoir is based on memory, therefore anything I write is inherently flawed. A lot has happened in half a century, and my memory isn’t what it used to be. And to prevent writing how most of us talk in daily chatter, full things like “um,” “hmm,” “what’s for dinner,” and “Dude,” I compress conversations into dialogue, “so that what’s said moves the story along.” But I cite quotes in media whenever I can, and I try to weave a story that’s as true as possible given our ignorance of what happens behind the scenes of public documents. And sometimes, to keep the voices at a reasonable volume, I blend a few childhood friends and old army buddies into single characters; otherwise, it would be sipping water from a fire hydrant. Trust me, I know: The JFK Assassination Report is based on a massive collection of documents that fills a medium sized government library, downloadable with 2001-era technology in about an hour and a half, and even with fancy programs it’s a lot to digest, not to mention the 2,000 or so books on Amazon and 10,000 blogs by wiki-esque sleuths. It’s hard to separate fact from mistaken but regurgitated information. To me, memoirs are the closest thing we have to analog copies of what happened, and every day there are fewer and fewer of us left alive to share our memories.

By the time of Covid in 2020 to around 2022, the internet was faster and I wrote programs to simplify my search. Again and again, I found that the foundation of my beliefs were based on faulty memories. One that surprised me most was after the Louisiana High School Athletic Association dug up hand-written wrestling results from the 1980’s and posted them on LHSAA.org. New evidence, to me at least, proved that Hillary Clinton didn’t break my finger: Hillary Moore did.

That hurt my brain at first. I was probably more shocked than you are right now. I called a bunch of old buddies and confirmed that, of course they said, Hillary’s last name was Moore (a few reminded me of that throw – it really was that good). You’d think I’d recall Hillary’s last name because he beat me so badly, but wrestling is not like that. We shook hands before every match and in front of a few fans and parents as representatives of each other’s teams at the Belaire-Capitol dual meets, but we never spoke. Not once. I can’t tell you what he sounded like. To me, he wasn’t anything more than A Boy Named Sue, stronger than Hercules and the three-time undefeated state champion that I had set my sights on. The term hero’s journey had just entered mainstream vernacular, with films like Star Wars, The Karate Kid, and more: Hillary was the Shoot in my Vision Quest, the thing lurking in Yoda’s tree cave that Luke Skywalker had to face. Like Luke carrying his light saber to face his demons, wrestlers sometime carry things onto the mat with them. That’s what coach meant: Just wrestle. Names didn’t matter. Neither did winning. That’s what I learned from wrestling Hillary Clinton.

Maybe I remembered Hillary as Hillary Clinton because earlier that day I defeated the wrestler from Clinton high school to make my way to finals, and his name and school had been under Hillary’s for the next round. I used to see Clinton’s gym when I rode with Coach around southern Louisaina, delivering wrestling supplies during summer freestyle season; he’s credited with staring Louisiana Wrestling, and for getting the sport to what it was in 1990.5 And, obvious now in hindsight, I probably made a mistake with Hillary’s name in 1992, when incumbent president Bill Clinton sparked to the world finally know about Hillary Clinton.

At that time, just before I first read the JFK Assassination Report, I was in the All American pre-Ranger course. Around 5,000 Rangers graduate a year, and a few come from the All Americans. Competition is fierce and elitist to represent the 82nd Airborne among all other teams. Of the 268 E4 to E8 paratroopers, already adorned with airborne and air assault and combat badges, that removed our ranks and our badges and began the two week course, only nine of us crossed the finish line. Of the nine of us, six wrestled in high school, two also in college. As we ate and slept for the first time in longer than we could recall, we swapped stories, and because of the remarkable statistics of us having wrestled, we chatted about wrestling, why we crossed the line and others didn’t, sacrifice, cutting weight, coaches, teammates, luck, and more. We spoke of what spoke to us from memories from our youth. I was 19, and that was the first time I told the story about Hillary Clinton and held up my Spock-like left hand to show the proof. (I omitted the parts about Big Daddy’s funeral, Jimmy Hoffa’s tale, and any thoughts on who may have killed President Kennedy and why, for what I hope are obvious reasons.) Everyone laughed, and the name stuck. Thirty years passed, and I probably told that joke and held up my hand a hundred times or more.

Today, my memory of wrestling Hillary Clinton is indistinguishable from a real memory, strengthened every time I made a joke about Hillary’s name and showed my poorly-healed finger and mimicked Spock’s monotoned blessing: live long and prosper. I can still see the other wrestlers in my mind at that match, people I knew from freestyle like Colothian Tate, captain of the Baton Rouge High Bulldogs, who won AT 136 and was voted most outstanding wrestler, and would go on to win state and wrestle for Iowa; my co-captain of the Belaire Bengals, Jeremy Gann, who won first at 142, would win second in state, and go on to still be a man of few words who helped his kids and their teams wrestle; and Hillary, captain of the Capitol Lions, who would win state at 145 and I’d never hear from again, but rumors are that he’s still alive and kicking. We all got together now and then, and a few of us would wrestle in the annual Meterie Old Timer’s tournament and keep in touch for more than thirty years.

And most importantly to me, after wrestling on Fort Bragg’s team and being honorably discharged with a chest full of medals and stack of papers that called me an All American hero, I proudly served as Coach’s assistant for the Belaire High Bengal wrestling team. Big Rodney, our heavyweight, still coaches Louisiana teams, and Little Paige Russel would wrestle in college then, while in the air force and stationed overseas, become South Korea’s midweight MMA champion. For years, I watched Coach shake each wrestler’s hand the same way, and tell them they did a good job.

Coach passed away in 2014, but never once in 24 years did we discuss the past, other him tossing out a few of anecdotes about wrestling and lessons from his coaches. I can only imagine what we could learn if he were still around. As one commentator wrote before Coach’s funeral, before we knew of his Alzheimer’s therefore the sentiment should be heard rather than a jab, Coach Dale Ketelsen had forgotten more about wrestling than most of us will ever know. After his passing, when Louisiana finally renamed the Robert E. Lee memorial tournament the Coach Dale Ketelsen memorial tournament, everyone said it was about time.

In a memoir, words mean less than how a moment impacted you. Hillary was a beast, and a beast by any other name would have thrown me just as savagely. Regardless of the official results, I won that match in 1990. It’s not about your opponent, it’s about wrestling, and someone I love and trust told me I did a good job.

Given those disclaimers, this story is true.

Go to the Table of Contents

- From “Hoffa: The Real Story,” his second autobiography. The first was a flop penned in prison, “Hoffa on Hoffa.” The second polished with the help of a cowriter and editor: “Hoffa: The Real Story” was penned by James R. Hoffa and Oscar Fraley (Editor), and was first published on 01 January 1971, then re-published by Stein and Day on 01 October 1971; as of now, there are ten editions, and I quote from my grandmother’s first edition.

↩︎ - I copied the blurb about Big daddy from Wikipedia on 27 December 2024; it was:

Edward Partin

Edward Grady Partin Sr. (February 27, 1924 – March 11, 1990), was an American business agent for the Teamsters Union, and is best known for his 1964 testimony against Jimmy Hoffa, which helped Robert F. Kennedy convict Hoffa of jury tampering in 1964.[1]

Teamster Union and mob activities

Partin was the business manager of the five local IBTbranches in Baton Rouge for 30 years. In 1961, he was charged by the union with embezzlement as union money was stolen from a safe. Two key witnesses in the grand jury died. He was indicted on June 27, 1962, for 26 counts of embezzlement and falsification and released on bail.

On August 14, 1962, Partin was sued for his role in a traffic accident injuring two passengers and killing a third. He was also indicted for first-degree manslaughter and leaving the scene of an accident. He also surrendered himself for aggravated kidnapping.

He was finally convicted of conspiracy to obstruct justice through witness tampering and perjury in March 1979.[2] Partin pled no contest to numerous other corruption charges in the union, including embezzlement, and was released in 1986.[3]

Testimony against Hoffa

In 1963, Jimmy Hoffa, the president of the Teamsters, was arrested for attempted jury tampering in attempted bribery of a grand juror of a previous 1962 case involving payments from a trucking company. Partin testified that he was offered $20,000 to rig the jury in Hoffa’s favor. The testimony was the primary evidence of the Justice Department that led to Hoffa being sentenced to eight years in prison.[4] The entire case rested on his testimony and he was considered the lone witness.

Partin denied under oath that he was compensated by the Justice Department, but it was revealed that his ex-wife had her alimony payments given to her by the department. He originally denied that he would receive immunity or retroactive immunity for his testimony but it was later altered when he was under oath at a grand jury trial.[citation needed]

See also

J. Minos Simon, a Partin attorney

Blood Feud (1983 film)

References

“Edward Partin, 66; Union Aide Became Anti-Hoffa Witness”. The New York Times, March 12, 1990. March 13, 1990. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

Ap (1990-03-13). “Edward Partin, 66; Union Aide Became Anti-Hoffa Witness”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-12-19.

“Reading Eagle – Google News Archive Search”. news.google.com. Retrieved 2019-12-19.

“Reading Eagle – Google News Archive Search”. news.google.com. Retrieved 2019-12-19.

↩︎ - See Hoffa vs The United States, 1966 US Supreme court records. ↩︎

- That’s my opinion, and I’m not a lawyer. But it’s similar to what’s written in Hoffa vs. The United States by Chief Justice Earl Warren, and he was a lawyer. Warren was a 40 year veteran of the U.S. Supreme court, and the only one of nine justices who dissented against using my grandfather’s testimony to convict Jimmy Hoffa. (Two abstained.) In his missive explaining why he dissented, permanently attached to the court records and in the U.S. National Archives since 1966, Warren references Edward Partin 147 times. Here’s an excerpt:

“This type of informer and the uses to which he was put in this case evidence a serious potential for undermining the integrity of the truthfinding process in the federal courts. Given the incentives and background of Partin, no conviction should be allowed to stand when based heavily on his testimony. And that is exactly the quicksand upon which these convictions rest, because, without Partin, who was the principal government witness, there would probably have been no convictions here. Thus, although petitioners make their main arguments on constitutional grounds and raise serious Fourth and Sixth Amendment questions, it should not even be necessary for the Court to reach those questions. For the affront to the quality and fairness of federal law enforcement which this case presents is sufficient to require an exercise of our supervisory powers.

From the United States Library of Congress “Hoffa vs. The United States”

Title: U.S. Reports: Hoffa v. United States, 385 U.S. 293 (1966)

Names: Stewart, Potter (Judge); Supreme Court of the United States (Author)

Created / Published: 1966:

↩︎ - Coach passed away in 2014. When I began writing this, his oldest son, Craig, was head coach at St. Paul’s School in Covington, Louisiana, and on the board of the LLHSA. When I asked Craig if I could use Coach’s name in a memoir I was writing, he asked Mrs. K and Penny, and they all gave me their blessing. What they wrote about him was, like Coach, concise, humble, and truthful.

Dale “Coach” Glenn Ketelson Obituary: 2014

Dale Glenn Ketelsen, 78, Retired Teacher and Coach, passed away March 22, 2014 at Ollie Steele Burden Manor with his wife by his side. A Memorial service will be held Saturday, March 29 at University United Methodist Church, 3350 Dalrymple Drive. Visitation will begin at 10 am with a service to follow at 12 pm conducted by Rev. Larry Miller. Dale is survived by his wife of 52 years, Pat Ballard Ketelsen, 2 sons: Craig (Emily) Ketelsen of Covington, La; Erik (Bonnie) Ketelsen, Atlanta, Ga and one daughter, Penny (Lee) Kelly, Nashville, TN; 5 grandchildren: Katie, Abby, Brian and Michael Ketelsen and Graham Kelly; a Sister-in-Law, Karen Ketelsen of Osage, Iowa, and numerous neices and nephews. He was preceded in death by his parents, 2 sisters and a brother. Dale was born in Osage, Iowa where he attended High School, lettering in 4 sports. Upon graduation, he attended Iowa State University as a member of the wrestling team where he was a 2 time All American and won 2nd and 3rd in the NCAA finals in Wrestling. He was a finalist in the Olympic Trials for the 1960 Olympics. After graduation, he joined the US Marine Reserves and returned to ISU as an Asst. Wrestling Coach. In 1961, he took a job as Teacher/Coach at Riverside-Brookfield High School in Suburban Chicago, Ill. While there, he also earned a Masters Degree from Northern Illinois University. In 1968, he was hired to start a Wrestling program at LSU in Baton Rouge, La. He was on the Executive Board of the National Wrestling Coaches Association and a founding member of USA Wrestling. He was the wrestling host for the National Sports Festival in 1985, He was instrumental in promoting wrestling in the High Schools in Louisiana. He was head Wrestling Coach at Belaire High School for 20 years and Assistant Wrestling coach at The St. Paul’s School in Covington, La. He was devoted to Faith, Family, Farm and the sport of Wrestling. Among his many honors were induction into the National Wrestling Hall of Fame and being named Master of Wrestling (Man of the Year) for Wrestling USA magazine. He was a long time member and Usher of University United Methodist Church. In lieu of flowers, the family asks that donations be made to Alzheimer’s Services, 3772 North Blvd., Baton Rouge, La. 70806.

Published by The Advocate from Mar. 26 to Mar. 29, 2014.

According to online reports, he revived a high school team in Iowa that went on to win a conference championship, produce 30 all-conference wrestlers, 20 district champions, eight regional champions and two state titlist; in the twelve years as head coach of the new LSU program, his teams won two SEC Intercollegiate Wrestling tournaments, and produced 15 individual conference champs, and rose LSU to be ranked 4th in the nation, surpassing even Iowa. As a young man, he wrestled at 126 pounds. At the weakest point in life, Coach was stronger than my grandfather ever was. May they both rest in peace.

↩︎