Meditation on the Buddha’s final words

Beggars shouted at me and tugged my backpack as soon as I walked across the border from Nepal into India. Several crippled men were dragging themselves across the dirt road to join a man without legs clutching my pants as he begged for money. Healthy men shouted that they worked for the passport agency or bus company so I should pay them to get through the border and on a bus out of town.

I saw the border-control office and choose to quickly get there by stepping over the crippled man, shaking my leg free from his hand. Don’t judge: witnessing poverty is different than reading about it. The most compassionate of us make hard choices in these situations, especially when those choices are made quickly in an unfamiliar setting.

For the next five hours several passengers and I tried to repair a tire that had already been repaired multiple times. The inside looked more like a quilt of thin rubber patches than something you’d want between you and the road. We removed multiple tires, looking for ones with the least damage or thickest patches, and tried making new patches from salvaged scraps.

If forced to choose, I’d keep my passport, money, and Frisbee rather than my bag of clothes. I can buy new clothes, but Frisbees are unavailable in most of the world and have opened more opportunities for me than money. Sharing a fun moment leads to friends who help you along your way.

People began abandoning the bus to find a ride anywhere else. I decided that anywhere else would be better than my current location of somewhere else, so I ended up hitchhiking and caught a bus that took me to a train station, where I boarded the first one headed in the general direction of Kushinagar, India.

The vendors dressed according to local traditions and prepared foods that reflected their cultures. I sampled cuisine from across northern India on a single train ride.

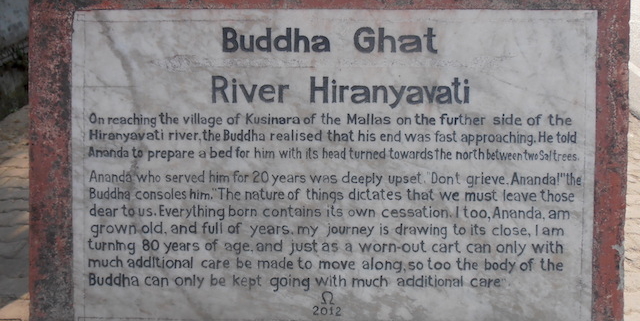

I had arrived late at night, but fortunately met someone who led me to a monastery that hosted guests, one of several funded by Asian countries so their citizens can take pilgrimages to Buddhist sites in India. The next morning, I grabbed my yoga mat and walked to the river where the Buddha chose to be cremated. I had read that the site was marked by a ghat, a concrete platform and stairs that Hindus use to access holy rivers. I was tired and sore, with a throbbing headache and spasms between my shoulders, and looking forward to unwinding and re-centering with yoga and meditation at the Buddha Ghat, which I imagined would be as peaceful and serene as the story behind it.

I was disappointed at the ghat but when the bus had broken down I had fun. Something about my expectations for each event created physical connections in my brain that affected how I reacted. I knew this intellectually, and my intellect would chose to always have fun, which is why I starting thinking about what happened in my mind that overrode my intellect, especially the subtle physical sensation I felt from disappointment.

Does the name Pavlov doesn’t ring a bell? (ha!) Pavlov’s dogs were conditioned to salivate at the sound of a dinner bell, even when there was no dinner, showing how our minds condition physical responses. More recently, brain-imaging has shown that our bodies react micro-seconds before our brain evaluates a situation. In other words, attachment to happens before thoughts develop.

I wanted to analyze where my attachment began, which requires concentration. It’s easier to concentrate on something external, such as working, watching a movie, or reading a book, than it is to concentrate on your mind. I wanted to understand the phenomenon so I laid out my yoga mat and did about 30 minutes of yoga before meditating.

Meditation according to eastern philosophy isn’t what most people in the western world envision. In the Buddha’s language meditation was a concept that combined concentration, analysis, and mental development. To meditate is to concentrate on one thing and analyze it, developing your understanding on a level deeper than words can express. Meditation is related to mindfulness, being aware of your mind and body sensations without judgement or attachment, seeing them on a deeper level than conditioned thoughts.

Try it for ten minutes. Be neither full nor hungry, tired nor restless, and sit in a comfortable position so there’s no reason to want to move. Be completely relaxed. Can you concentrate on your breath or body sensations for ten minutes without a single thought popping into your head? Five minutes? One minute? I was surprised by how hard it was when I first started practicing.

After 20 to 40 minutes of meditating near the plastic trash and human feces I saw the moment with more clarity and it was beautiful. I’m not saying I saw the trash and turds as beautiful, I saw the moment as beautiful. I couldn’t have seen that beauty with attachment to anything, even something perceived as positive. That statement makes more sense in my head than in words because I don’t have the words to describe it. But, I can list a few things and try to paint a picture of the experience.

I felt relaxed, without expectations, and wasn’t looking for anything therefore I noticed more. Not just the things I’m describing but things I don’t know how to express in words

I felt relaxed, without expectations, and wasn’t looking for anything therefore I noticed more. Not just the things I’m describing but things I don’t know how to express in words

Across the river, a family brought their herd of goats to drink as their children played near the water, creating a mirror image thanks to the murkiness of the water.

The teenagers drove their motorcycles to a bridge and chased each other through the small waterfalls formed under the bridges support columns, laughing and enjoying their moment unaware of the ugliness I had seen earlier.

A kingfisher bird darted between a tree branch and the water surface, snatching his dinner from the murky water and flashing his bright underbelly and tail feathers each time.

Lotus petals have an electric charge that makes them hydrophobic. In other words, water is repelled from their surface by electrical force. It gets better… the petals are micro-textured with the size and spacing necessary for water to bead up, scraping away dirt as it forms a ball and rolls off the hydrophobic surface, leaving a brightly colored flower. From an evolutionary standpoint this is brilliant (ha!) because it maximizes energy from sunlight, and bright flowers attract more insects that help the lotus plant propagate. The lotus flower has been on Earth for millions of years, so our ancestors would have noticed the phenomenon and attributed it to mysticism or used it as a metaphor.

I’ve seen lotus flowers used in temples of India, Asia, and Egypt to communicate concepts before humans developed written languages. Since the invention of writing, Hindus in India have written about the lotus as a metaphor of the intention behind their religion.

The fog lifted, literally, (ha!) and I stood up to leave. For the first time, I saw a rock building towering above the trees, and realized it was the stupa encasing ashes of the Buddha. I walked around the fenced compound and entered the pristine gardens, joining several groups pilgrims and monks in meditation.

I slept at the monastery again, waking up early to explore more of Kushinagar. I found a small temple with a 1,500 year-old statue of the reclining Buddha, depicting when he said his final words before passing away.

Pilgrims from all over the world would come and go. I sat cross-legged for several hours, observing while meditating. I saw groups from two countries show up and share the experience rather than focusing on what they expected. The groups evolved into a chant despite not speaking the same language. I listened to their voices resonate for an hour.

Pilgrims from all over the world would come and go. I sat cross-legged for several hours, observing while meditating. I saw groups from two countries show up and share the experience rather than focusing on what they expected. The groups evolved into a chant despite not speaking the same language. I listened to their voices resonate for an hour.

Six months after leaving Kushinagar, I consider turds on the Buddha Ghat a metaphor for ourselves and our choices. Physically, when I desire relief from pain I become attached to that desire and reduce my ability to perceive pleasure. Not that I don’t work towards physical health, but I’ve experienced lack of joy for long periods of time when my physical pain didn’t match my expectations. Similarly, I’ve made difficult choices, such as leaving the boy on the street in Lumbini and stepping over a crippled man to get my passport stamped, or many things in San Diego where I could be doing more to help others but chose otherwise. I’m a mixture of turds and kingfishers. To see what is wrong is to suffer and to not see what is right is to suffer. To be attached to wrong or right, ugly or beautiful, leads to a form of suffering.

I slept at the monastery for one more night, then early the next morning I walked through a thick fog, both literally and figuratively. I stood in the fog with my backpack, waiting for a bus by the same highway where I had been dropped off a few days prior. I knew the bus and trains would lead to physical discomfort. I saw a hint of attachment to hope that things would improve and smiled at how quickly old habits can return. Conditioned behavior is a habit than can be unlearned by mindful meditation.

This is a good time to share the Buddha’s final words. It’s more of a story than a sentence, with him ensuring the person who cooked his last meal knew the food was unrelated to his death, and emphasizing that he was only human and that they had everything they needed to continue without him. He asked if anyone had doubt about his teachings in a way that ensured no one would be embarrassed to speak out. Hundreds of monks replied that they had no doubt, and the Buddha spoke his final words.

His final words don’t translate to English well. He used the Hindu concept dukkha, which is approximately translated to “suffering” from obvious causes such as death, disease, and sadness but includes includes worry, anger, disappointment, impatience, judgement, or any unrest of the mind. Dukkha is anything other than experiencing a moment for what it is, remaining unblemished like a lotus flower shedding dirty water.

My paraphrasing of the Buddha’s final words is: