Wendy was WARPed

My mom used to joke that she was born Wendy Anne Rothdram, WAR, and that marrying a Partin WARP’ed her. I never understood that joke as a kid, and I didn’t even know Wendy was my mom for many years.

Wendy and my dad, Ed Partin Jr., were married briefly. They had dropped out of high school to have me, and had eloped to Mississippi, two hours upriver, because, unlike most states, Mississippi state law didn’t require parental approval for kids to marry. But, all states honor Mississippi marriage certificates, and they returned to Baton Rouge as husband and wife and began living in one of Big Daddy’s houses.

Soon after I was born in 1972, my dad took off for Miami on his motorcycle with his friends, and they took a boat from Miami to either Jamaica or Cuba to buy drugs and bring them back to Baton Rouge. He was gone for a several weeks, and Wendy was alone in Big Daddy’s house, and, as she’d repeat in family court records for the next seven years, she found herself married to a husband who did not love her, and she felt lonely and scared and alone. She saw handwritten note on a coffee shop wall asking to share gas driving to California, and, impulsively, she left with him, abandoning me at a daycare center.

Her best friend, Linda White, was my emergency contact. The daycare center called Linda when Wendy failed to pick me up, and Linda’s dad, Ed White, took me home when they couldn’t find someone else that late in the evening. He called the police, and a judge removed me from my Partin family’s custody, citing Wendy’s intemperance and my dad’s disappearance and criminal history, and also because all Louisiana judges knew my Partin family well. The judge appointed Ed White as my legal guardian, giving him authority to choose when Wendy and my dad saw me. For the next few years, I knew Ed White as PawPaw.

PawPaw was the most respected tree surgeon in southern Louisiana, and he worked mostly during summer insect season to protect old oak trees, and after the winter hurricane season to repair broken branches. During those seasons, he hired newly released male convicts and trained them to become landscapers or even tree surgeons. Off season, he ran the Baton Rouge franchise of Kelly’s Girls, a business that placed young, uneducated women in unskilled or secretarial jobs so they wouldn’t be dependent on people who may not treat them well. Through Kelly Girls, he had a contract to deliver telephone books every spring, and he paid young ladies to deliver them on their own schedule so that they could attend school or look after their children. He’d lend them an old car, if they needed one to work for him. He showed young adults who didn’t have their own mentors how to earn their livelihood without a high school diploma, and it makes sense that he’d meet my parents, Ed and Wendy Partin.

My first memory of Wendy was when my hair was still growing out after my stay in Our Lady of the Lake Hospital. She and her friend Debbie showed up at PawPaw’s and loaded Debbie’s car so full of bright yellow telephone books that I had to sit on the front seat’s center arm rest with books stacked behind me. Wendy drove, and Debbie chatted with me and asked to see my scar. I rotated my head, and Debbie inspected my scar and commented how brave I must have been. I agreed, and told her about the hospital and color television. We chatted back and forth about which cartoons I liked for a while, and I told her about Popeye, who looked and sounded like PawPaw – they even both smoked a lot, and PawPaw had been a sailor in WWII, too. It was only a coincidence that Popeye looked after Olive Oil’s baby, Sweet Pea, and protected them from the big Brutus; mostly, I liked the Popeye theme song every time he ate his spinach and grew bug enough to fight Brutus.

I finished telling Debbie about Popeye, and she and Wendy began delivering phone books, picking up one from the back seat and carrying it to doorsteps in a neighborhood not too far from PawPaw’s. Soon there was enough space for me to sit on a small stack of them in the back seat, and Debbie rotated so she could see me and we could chat more about color television and Popeye and fishing and MawMaw’s cookies while Wendy drove us in and out of a few more neighborhoods. Wendy would interrupt us occasionally to point out all of the nice houses and their beautiful yards; it was springtime, just after winter hurricane season, and the azeleas were blooming bright red under the stately oaks with their dark green leaves with grey and black Spanish moss hanging down. When we stopped, Wendy would pick an azelea and sniff it and hand it to Debbie and me to smell. They smelled nice, but not nearly as nice as freshly baked chocolate chip cookies.

When we ran out of telephone books, Wendy got back on on the interstate and Debbie pulled out a small bag, put it on her lap, and rolled a joint with almost as much deftness as my dad; though, in fairness, she wasn’t driving with her knee while rolling it.

Debbie lit the joint with her cigarette lighter, took a drag, handed it to Wendy, and cracked her windshield to exhale up and out the car. Wendy took a drag and handed it back to Debbie and exhaled out the crack in her window, and they passed the joint back and forth and laughed so much that I was having fun with them despite not getting high from the second hand smoke that escaped their windows.

They finished the joint quickly – Debbie rolled them much smaller than my dad or Sonny – and we we laughed all the way to where Wendy and Debbie sometimes stayed. It was a remarkable house, brightly painted with dancing figures of abstract people, and swoops and swirls of colors and psychedelic symbols, and was occasionally in the news simply because it was so unique. I was surprised to see Craig Black there, not knowing he was an artist and, before he and Linda had a baby, had shared the house with his high school friends who were still living there four years later. But, he was tired and sluggish, like most people there, and didn’t seem to recognize me. The air was thick with smoke – no one cracked windows in their psychedelic house.

Wendy introduced me to a few of her friends, but I don’t recall their names. One guy, though, stuck out: Bryan, the one armed drug dealer. He had big, bushy hair, almost like an afro, and a wide smile, and he remembered me and said my name correctly. Bryan had lost one arm in a drunk driving accident on his motorcycle, and could roll a joint with only one hand. I thought that was the coolest trick I had ever seen, and I gravitated towards him the rest of the day. He never seemed to get sluggish, and was always smiling and joking with Wendy.

I had fun with Wendy and Debbie and Brian, but I was tired and feeling sluggish by the end of the day. Wendy said she had to take me back to Mr. White’s, and I fell asleep soon after we got in her car and were back on the interstate.

I didn’t sleep long, because Wendy was speeding and a police car pulled her over. I woke up with Wendy shaking me, explaining to the policeman standing outside her window that her little brother was sick and she needed to get me home quickly. He looked at me and asked my name, and I told him Jason Partin, and he looked at Wendy’s driver’s license in his hand and told her to drive more slowly, and smiled at me and said he hoped I felt better. I didn’t know what to say – I had never spoken to a cop in uniform before – so I said nothing. But, I was probably smiling – I had inherited Bug Daddy’s subtle smile – and the officer smiled back and probably mistook my silence for shyness, and told Wendy to get home our parents safely.

Wendy laughed on the way home, said I did a good job of ‘playing it cool,’ and asked me not to tell Mr. White about the policeman or seeing Craig or Brian.

She dropped me off at PawPaw’s. MawMaw wss the only one home, and I was so hungry that I instantly forgot about the day. I wiped MawMaw’s red lipstick shuggah’s off my face, and asked her what was for dinner and asked if she had any cookies. We did, and they were probably the most delicious cookies I had ever eaten. I devoured three of them and was still hungry and anxious for dinner. It was as if I had the munchies.

A few months later, I began spending nights with Wendy on my monthly visit, not just day trips while she worked for Kelly’s Girls. At first, we’d stay with Auntie Lo and Uncle Bob. They lived in a big house in a nice all-white neighborhood called Sherwood Forest, and I even had my own bedroom there. Behind the house was Westminister Elementary School, which didn’t have kids bussed in and only served Sherwood Forest kids. The school was empty on weekends, and Wendy would walk me there and play with me on their playground. It was almost as much fun as PawPaw’s oak tree swing.

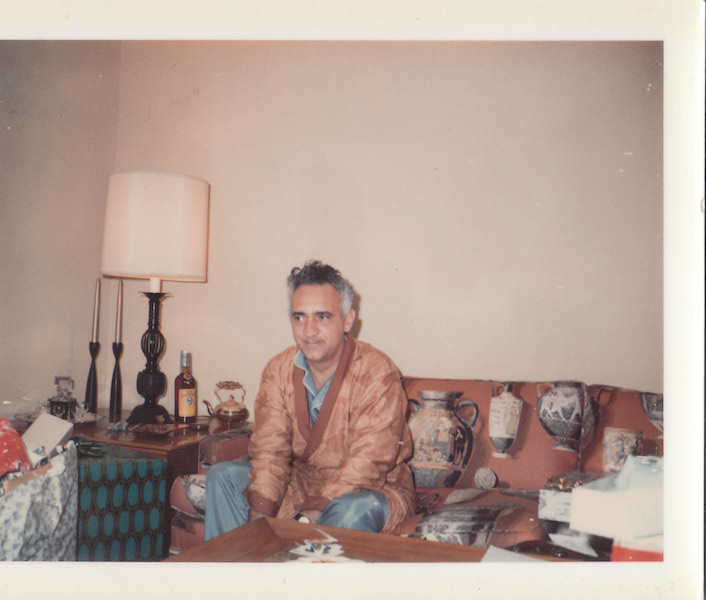

Auntie Lo and Uncle Bob were nice, but they never walked to the playground to play with us, because Uncle Bob and Auntie Lo liked to play golf at the Sherwood Forest Country Club on weekends then relax with a few glasses of Scotch while Auntie Lo cooked dinner. But, they kept lots of art supplies for me around the house after I told them about Craig’s art and how much fun he and his friends seemed to have painting, and they would sit with me at the dining room table after dinner and sip Scotch while I drew and painted. Usually, Wendy would leave after dinner. I think she liked Bryan, and was trying to spend time with him without anyone else around.

Uncle Bob and Auntie Lo’s yard had lots of azaleas, though they stopped blooming by the time I began sleeping their. Auntie Lo said they only bloom in spring, and that she loved her azaleas and her pecan trees. She and Uncle Bob would take me walking around their back yard, picking up pecans before Uncle Bob mowed, and I’d help shell them for Auntie Lo to make a pecan pie. Uncle Bob didn’t eat deserts, but he’d sip his Scotch and smoke cigarettes while I ate at least two slices, and we’d peel extra pecans to mail to family in Canada. Uncle Bob said he was from Prince Edward Island, and I thought Prince Edward Island sounded like where my dad and grandfather and PawPaw came from, because I heard other people call all of them Edward.

I liked coming back to Auntie Lo and Uncle Bob’s. I had my own room, so I could leave things there and not have to pack them back into my backpack. They put my artwork up on the walls, next to Wendy’s ribbons from swimming meets and tennis tournaments, and sheets with her poetry writing. Uncle Bob would point them out, saying Wendy used to be an athlete and used to enjoy learning and writing. He’d emphasize Wendy’s neat handwriting, and say that Wendy used to care about a lot of things, and he’d ask me what I enjoyed doing. I told him fishing and hunting. I couldn’t do those things in Sherwood Forest, but I was growing to enjoy drawing and painting. After I said that, every time I visited there’d be new paint brushes or easels or books with blank pages and drawing lessons to practice. I became quite apt, and even made a little spare change selling my artwork to Auntie Lo for 10 to 25 cents each; she’d buy several, and ask me to add up how much she owed, and then how much change I should give her back.

Uncle Bob wasn’t always there. He worked about an hour downriver from Baton Rouge, in New Orleans, but Auntie Lo stayed home all the time. Both were unabashed alcoholics, and they radiated a joy of life, what Uncle Bob called la joire de vive. he said that la joire de vive stemmed from doing whatever they wanted without regrets. When Uncle Bob was home for weekends, they’d get sloppy drunk by 3 or 4pm every day, and Wendy and I would eat Auntie Lo’s dinners while they laughed and slurred their speech and occasionally stumbled over their furniture on the way to or from their generously stocked liquor cabinet in the formal living room. Wendy usually left after dinner, probably back to the brightly painted house or to Bryan’s trailer in the woods, and I stayed awake with Uncle Bob in the living room after Auntie Lo would pass out and snore loudly from their bedroom. We’d sit around the dinner table with Uncle Bob smoking and drinking and asking me about what I was enjoying doing lately.

Very rarely, Uncle Bob would go to bed first, and Auntie Lo would stay up cleaning the kitchen and having the time of her life drinking by herself and loudly washing dishes and talking about how nice their plates and glasses were. On one of those nights, I was asleep when I heard Auntie Lo’s loud and slurred voice punctuated by a clicking sound she made by snapping her tongue against her teeth and making a loud POP! that resonated throughout the house and was a bellweather that she was almost incoherent. When she began making that sound, Uncle Bob called it being three sheets to the wind, and even he stayed away from her flailing limbs.

Usually, she was still cheerful when three sheets to the wind, but that night she sounded angry, and her clicks came quickly and she slurred words I didn’t understand. As I became awake, I heard Wendy’s softer voice responding to Auntie Lo, defending herself for coming home late.

“We don’t look after Jason so you can come home drunk!” Auntie Lo mumbled, followed by a POP!

“You’re not looking after him, you’re drunk!” Wendy retorted.

“It’s my house and I’ll drink whenever I like!” Auntie Lo mumbled loudly. Good point, I’d recall years later. “We didn’t want him or you here!”

Their argument quickly escalated in volume and degraded into insults. A few minutes later, I heard the unmistakable Slap! of someone’s hand contacting someone’s cheek. An instant later, I heard another one. And then another. I got out of bed and crept to my door and peered down the hall to where I could see them in the kitchen.

Auntie Lo was a large woman, and Wendy was a petite girl. If you’ve ever seen Julia Child, the famous chef who towered over her guests on television, you’d have an idea of what Auntie Lo looked like and acted like when sober: large, flamboyant, unabashed, and with hands that waved through the air as she talked. In a way, she was charming and unthreatening when sober, the way we appreciate someone comfortable with who they are. But, when drunk, which was most of the time after 2 or 3 pm, her size and gestures were grotesque, especially contrasted against Wendy’s small frame and graceful movements from her days as an athlete.

Auntie Lo was leaning against a kitchen counter with her head hung low, but she snapped her head up every time she spoke or made that popping sound. Wendy was between her and the refrigerator, standing upright with her arms crossed and shaking. Her cheek was bright red. Auntie Lo’s nose was red, as usual. Behind me, I could hear Uncle Bob snoring in the master bedroom.

“I’m going to tell Robert that you hit me!” Auntie Lo proclaimed, followed by “POP!” The effort drained her, and her head slumped back down and she steadied herself against the counter.

“You slapped me first!” Wendy said in a shrill voice muddled by alcohol and tears.

“I’ll tell him you hit me first!” she bellowed after recovering from her slump. “POP!”

Wendy said something that I didn’t understand, but it sounded like a curse word and seemed to infuriate Auntie Lo, who swung her huge hand and slapped Wendy with surprising speed for her drunken state. Wendy reeled, then screeched and jumped forward and began swinging both hands wildly at Auntie Lo’s face, quickly and fiercely alternating left-right-left. Auntie Lo blocked the slaps, then heaved all of her weight behind a swing and sent Wendy flying into the refrigerator. The effort expended her focus, and she slumped onto the floor as Wendy screeched and turned towards me and rushed down the hall.

Her face red and swollen, and tears streaming down her cheeks. She pushed me inside the room and told me we were leaving, and ripped open my dresser cabinets and yanked out a few sets of clothes and packed them with surprising delicacy into my backpack, and held me by my arm as we left my bedroom. I noticed that Uncle Bob wasn’t snoring any more, and wondered if he’d come out and calm everyone down. He didn’t. He was a wise man.

Auntie Lo had somewhat recovered and was trying to stand up, and she reached out to grab my leg as Wendy rushed us past her and out the carport door and to her car. She was crying and not looking at me, but kept telling me everything would be okay and that we were going to Debbie’s. She backed out of the driveway and sped down the street, and a few minutes later we were on the interstate. We soon arrived at Debbie’s mom’s apartment, and Wendy held my hand as we knocked on the door. It was late, but Debbie and her mom and brother were awake and watching television. They invited us inside without questions, and Debbie’s mom opened a bag of cookies for me to snack on and yelled that we were welcome to stay as long as we needed.

She always yelled, no matter what her mood, and always seemed to have bagged candy for me whenever we visited. They were on state disability for mental illness, and were given just enough to afford a tiny apartment in a bad part of town, a television, and a cabinet full of cheap snacks. Debbie’s mom had szizophrenia and couldn’t work, Wendy had told me, and Debbie lived there with her mom and younger brother. They were always nice to me, but I was anxious to leave because I didn’t like their cramped little apartment with its blaring television and their loud voices; it was like being in the middle of a family fight all the time, even when they were being nice to each other and me. And I never liked prepackaged cookies as much as freshly baked – they were crumbly instead of chewy, and cold instead of warm.

Only Debbie was soft spoken, and I sat next to her while her mom tried to calm Wendy by shouting motherly advice. Debbie and I ate crumbly cookies and chatted about both of our art projects. I told her that I was selling my paintings, and she showed me some bracelets she was making from beads. She gave me one, and told me that everything was going to be okay. I didn’t know why people kept saying that, or even what it meant, but somehow Debbie’s tone led me to believe that everything was already okay. Somehow, even the crumbly cookies tasted good with Debbie around.

We stayed there two nights, and I lived out of my backpack again. When I was dropped off at PawPaw’s, no one told me what not to say, so after I wiped off MawMaw’s shuggah I told them what happened. MawMaw seemed upset, but PawPaw smiled and took me fishing and told MawMaw that baking cookies would calm her down. He was right, and everything turned out okay.

The next few years of monthly visits with Wendy weren’t as consistent or predictable as they were with my dad. She was trying to find a job with health insurance that paid enough for her to afford an apartment with a separate bedroom for me. Those were requirements from the judge who had removed me from her and my dad’s custody, and were necessary before either of them could petition to regain custody. She would complain that no one wanted to hire her because her last name was Partin, though Uncle Bob suggested it was because she didn’t have a high school diploma and kept hanging around her hippie friends at their art colony. As they moved, we’d follow, and sometimes we’d stay with Debbie’s family, and sometimes we’d stay at Bryan’s trailer, and sometimes we’d stay in places only one time that I’d never see again or remember.

I began spending more and more time at Uncle Bob and Auntie Lo’s because I began kindergarten in August of 1977; and, according to what I remember being said, they lived near a good school but PawPaw lived near a black school. At first I thought that meant Craig Black’s art studio, but I was only four years old and prone to mistakes, just like my dad.

I was born on October 5th, two days before the age cut-off for kindergarten, so I began school at age four. If I had been born two days later, I would have had to wait a year. Instead, I began school as the youngest kid in class, and that’s a significant and under-appreciated difference. Most adults didn’t consider that a year is 25% of a kindergartener’s life, which is akin to being a 12 year old trying to learn and play with 16 year olds who were bigger and had four years more experience. Years later, this difference would be emphasized in popular books that showed, statistically, that the best Canadian hockey players had the same birth month, and that they had begun kindergarten as the oldest and biggest kids, and therefore were always the best hockey players in class, and therefore were placed with other good hockey players every year, and collectively, over time, they rose above the younger, smaller kids and became celebrated hockey players.

I was the smallest and least literate kid in Miss Founteneaux’s kindergarten class, and though she made all of us feel safe and special and loved, the other kids knew I was her favorite. Not because I was smart or handsome or charismatic as Big Daddy, but because I simply loved being there. I looked forward to every day, and as soon as Auntie Lo let go of my hand after walking me to school I’d run to Miss Founteneaux’s room with my backpack full of art supplies and my knife in my pocket and give 100% to everything she asked. And she was pretty. And she smelled nice. I was sure we’d marry one day.

I’d have to walk back home alone, because by 2:30pm Auntie Lo was at least two sheets to the wind and unstable on her feet, and oozing the smell of Scotch from every pore in her large body. I’d arrive home to a pot of something simmering on the stove and her soap operas on television. I’d grab a few snacks she’d have waiting and go into her bedroom to watch after-school shows on PBS. That’s how I knew she looked and sounded like Julia Child, and why, for a while, I thought that Craig Black was the hippie painter of trees, Bob Ross, and that PawPaw was the Cajun chef Justin Wilson. That made sense to me, especially because I was used to seeing Big Daddy on television and the news all the time, so I naturally assumed that all of my family were famous.

Wendy would pick me up at PawPaw’s on Sunday evenings and drop me off at Auntie Lo and Uncle Bob’s. I’d be back at PawPaw’s by Friday evening, usually before Uncle Bob returned on weekends. Wendy wasn’t allowed to stay there any more, but would still take me once a month to stay a weekend wherever she was living at the time. Uncle Bob wouldn’t allow my dad to pick me up at their house, so my weekends with him began and ended at PawPaw’s. The other two weekends were with MawMaw and PawPaw and Craig and Linda, the Whites and Blacks. Occasionally, Uncle Bob would be back in Baton Rouge early, and I’d spend a Thursday and Friday with him; he was the only person I’d leave kindergarten early to go see. He always spoke with me as if I were an adult, and never seemed anxious to be somewhere else or doing something else, like Wendy or Auntie Lo.

It was a fun life, despite the confusion. I was in love with Miss Founteneaux and best buddies with Uncle Bob; unrestricted by Auntie Lo therefore able to do whatever I wanted after school; and able to see Debbie with Wendy. I was a fierce rabbit hunter with my dad; a mighty fisherman and budding Tree Surgeon with PawPaw; and recipient of boundless cookies and shuggah from MawMaw. I was happy.

All of that ended the Christmas of 1979. I recall the time for several reasons. First, it was the last time I saw Big Daddy pull a knife on my dad, and the last time I’d see him before he began his prison sentence. And, because I watched news with Uncle Bob and listened to him, it was the year that a few hundred Americans had been trapped on an airplane by terrorists in Iran and American special forces died trying to save them. It was also the same year that some of my Partin family lamented the oil crisis and soaring gas prices, because it affected the Teamsters trucking profits so much, and they talked about the terrorists whenever they blamed President Carter for the oil crisis. It seemed that my family talked about Presidents more than most people’s, and everyone commented on President Carter’s handling of things and wondered if the newly elected president, a Hollywood actor named Ronald Reagan, would do better. I was only seven years old and didn’t understand anything they were saying, but the stories were so consistent and so frequent that the words stuck in my mind, especially because the only person who never discussed those things was PawPaw, and the last time I saw him was Christmas of 1979.

I was sitting around Auntie Lo’s huge, white frosted Christmas tree that she said reminded her of snow in Canada, the only thing she missed since moving to the warm southern climate, and were sipping eggnog and laughing about the untouched plate of cookies but empty glass of Scotch that was evidence Santa had visited. (Uncle Bob and I had discussed that Santa was not real – I had almost said bullshit at first – and he said that he wouldn’t lie to me, but he had asked me not to ruin the fun for Auntie Lo, and I agreed). Wendy and Debbie were there, and I was eating a second slice of pecan pie when PawPaw knocked on the carport door and opened it without waiting. He had a huge present wrapped for me, and when I tore it open I was unsure what it was. It was a big red pole with a giant spring on it, and I stared at it, perplexed. He laughed and asked if he could show me how it worked, and I handed it to him and he quickly jumped on it and began hopping up and down on the pogo stick like a bullfrog hopping around his pond. He laughed so hard that I laughed, too. But Auntie Lo got flustered and tried to get him to stop because she was worried about her hard wood floors getting scuffed. She asked him to leave. Wendy agreed. Uncle Bob remained silent, as usual, and Debbie smiled at me compassionately, like she always did whenever I seemed confused.

PawPaw lowered his head and asked if he could say goodbye to me outside. Wendy was my guardian by then, so she said yes and I followed him out the carport door and walked with him towards his old pickup truck. Wendy stood in the doorway and waited.

The blood stains were gone from his truck, but it still smelled like his cigarettes and diesel gasoline from burning trees on his farm. He bent down to look me in the eyes, smiled, and told me he loved me and hugged me. I was confused by how he was acting, but I hugged him back as always, and I told him I loved him. He released me and looked at me with tears in his eyes, and said, “I’ll always remember that funny joke you told me, Lil’ Buddy.” I asked which joke, and he said he once reached for his belt and I told him “Belts are for holding up your pants, not for hitting your Lil’ Buddy!” I didn’t remember saying that, but he asked me to tell it to him again, so I said it and he smiled and said that was it, and hugged me again and waved to Wendy in the doorway and got into his truck and drove off, back to his family’s Christmas.

I went back inside with Wendy and watched Auntie Lo scrub the scuff marks off the floor around her frosted tree. It was before noon, but she was already drunk from the heavily spiked eggnog, and angrily making POP! sounds as she complained about her floor. Later, without me knowing, she threw away the pogo stick. I never saw PawPaw again, which made 1979 was the saddest Christmas I can recall.