28 February 2019

“Edward Grady Partin was a big, rugged guy who could charm a snake off a rock.”

Jimmy Hoffa, 1975

My buddy John finally reached the punchline: “Partin’s going to find out that his grandfather fucked Castro up the ass and called him Jimmy!”

Our laughter drowned the din of about twenty people chatting inside. Five of us were on my balcony, overlooking Balboa Park to our east: 1,200 acres of rolling hills filled with dozens of gardens, museums, rolling bike trails, lush forests, and the San Diego Zoo. Less than a mile to our west, if we were in the condo of my neighbors and friends, Carleton and Linda, you’d see downtown skyscrapers, the airport, and the blue waters of San Diego bay. We were in America’s Finest City. It was late, and my friends were drunk.

Levi doubled over and spilled a bit of his beer, and Erin snorted like she does late at night. John closed his eyes and snuggled his Tecate, and his shoulders bumped up and down in silent laughter. Carleton stopped chuckling and stared skyward, pondering if there were any truth behind the joke; not literally, but in how my grandfather could have manipulated so many people.

“Dude,” I said, wiping a tear from my eye, “That was fucking hilarious!”

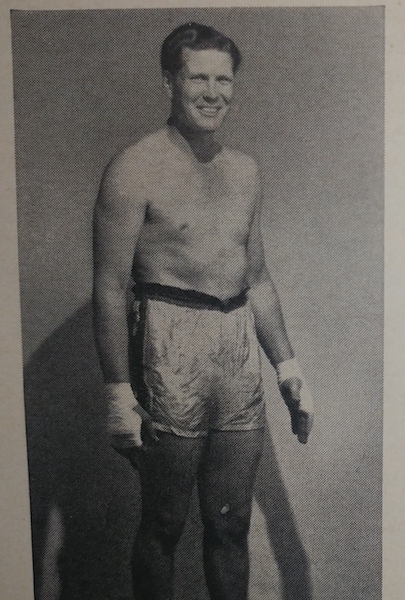

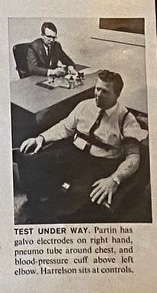

I’m Jason Partin, and I had recently showed my friends pictures of my family in Time magazine in 1964, the first time Hoover and Bobby showcased Big Daddy in media, and one of the photos Hoover chose was of my grandfather when he was younger, shirtless and smiling and sporting his boxing gloves, and another was Big Daddy strapped in a lie detector chair like some cheesy bondage porn film. John said that the cross-dressing homosexual Hoover was so enamored by my grandfather that he assigned extra FBI agents and federal marshals to follow my family, not to protect us from retaliation by Hoffa or the mafia, but to get more shirtless photos of Big Daddy. And Hoffa, after six years in a New Jersey federal peninitentary based soley on my grandfather’s word in a Chatanooga trial that Hoffa intended to bribe a juror, pounded mattresses eight hours a day on his work detail and summarized how Big Daddy fooled him by in chapter 10 of his autobiography, The Chatanooga Choo Choo, by saying, “Edward Grady Partin was a Big, Rugged Man who could charm a snake off a rock.” Almost every mob boss book from the time says something similar. John said all of that was evidence that Hoffa and the mafia were all closet homosexuals, which is why they let Big Daddy hang around them so much and spoke freely around him, like high school girls giddy around their star football player; and that’s how I remember everyone treating Big Daddy back in Baton Rouge. John’s joke was as good of a theory as any other I had heard.

Levi pushed his glasses up and rubbed his eyes. When our laughter dissipated, he popped opened a can of Tecate and asked, “What’s your plan?” he asked, making “rabbit ears” for “plan” with the can in one hand.

I shrugged. Levi rarely asks direct questions, but he had asked a fair question given the party’s occasion. I was leaving on an early morning flight to Cuba, the first stop on a three month sabbatical, in part to research my grandfather’s ties to Castro but mostly to meet an old friend, scuba dive, rock climb, listen to live music, and sip rum. I’d be gone almost three months, beginning with Cuba. The party was a going away gathering for friends, but I had invited some neighbors to join. They, like coworkers and colleagues and other people I knew casually, knew nothing about my family’s history. Gathering on the balcony allowed us to speak freely.

I reached for a beer out of habit, but stopped. I leaned back in my wrought iron chair, put a thoughtful look on my face to Levi him know I wasn’t ignoring him, and stretched my shoulders and rubbed my neck muscles. I didn’t have an answer, but I felt it was time to start something resembling a plan. To postpone answering, I scanned the view of Balboa Park while slightly exaggerating rubbing my neck, a habit I formed to let friends know I’d answer in a minute.

We were in a rare old building among the constantly evolving condos circling Balboa Park. Beside us, a historic building reportedly owned by a former president’s son but too expensive to preserve. It was one of the many early 1900’s buildings reminiscent of wild-west architecture, multi-storied with ornate wooden facades preserved in downtown’s lucrative gaslamp district, but unsustainable in the growing densely populated yet wealthy areas of Banker’s Hill. Every day, another building seemed to disappear to make way for yet another high-rise condo with underground parking. To our east was thousands of acres of forests and museums from the 1920’s World Expo; to our south was downtown, and to the west was the ocean, a Navy submarine base, and hints of the Navy SEAL training beach on Coronado Island. Hillcrest was north, with 183 restaurants crammed into a tight space but within walking distance of our relatively quiet residential neighborhood. For the next few years of construction next door, my balcony would have the grandest view in America’s Finest City.

My feet were perched on wrought iron that matched my chair and made the balcony look more like the architecture of downtown New Orleans than the insipid west coast modern style. To add to the image, across the street was a large southern Magnolia tree, mixed in with palm trees and the invasive drought-resistant sycamore trees planted by Balboa Park planners probably 80 years before, part of some garden exposition back when San Diego had more rainfall. Every spring, a family of owls nests in the Magnolia’s leaved branches, probably a welcome reprieve from the tall, thin palm trees that otherwise lined 6th Avenue; they were imported, too, but palm trees hide their thirst better than Magnolias, except to people who know those trees in their native habitats and can see the difference. To those of us who know, there’s a slight sadness at seeing displaced trees forgotten and neglected. Though our building was displaced architecture, it was meticulously maintained by a loving hand.

The owner of our building was Cranky Ken, an old-school guy who would be around my grandfather’s age, He had recently refused a $10.7 Million cash offer from Chinese investors who wanted to tear it down and build a multi-story building that would shade the sprawling southern Magnolia tree in front of us. If that happened, the 80 year old tree would fade away and die; it was already weakened from thirst in the dry southwest, and only maintained a few scraggly flowers rather than the skillet-sized and fragrant blooms back home. He grew up working the docks of New York City, where the biggest treat for him as a kid was to wander from his concrete jungle to gardens in Central Park and climb a tree. If anything made Cranky Ken less cranky, it was seeing kids climb that tree.

“Those chinks would have to pry this place from my cold, dead hands,” he told me early one morning when he stopped by my balcony to collect quarters from the building’s laundermat. His accent was like you’d expect from an old dock worker from New York, nasally and harsh.

When he was probably 35 or so, around Carleton’s age, Ken already aging too much to meet the demands of a stevedore. He somehow scored enough money in the early 70’s to move to the relatively nascent San Diego and buy a few buildings no one wanted, before it boomed and became America’s 7th largest city and every piece of real estate quadrupled in value. I never asked where he got the money, and though it’s easy to assume he and the other stevedore swiped something big from a shipping container, or he did something with the mob, which is always likely in big port towns like New York and New Orleans, the first and second largest ports in America. Stevedores vide with Teamsters for dock contracts back then, because Hoffa pushed to have his Teamsters represent everything on wheels, and the docs had motorized lift dollies, but I never asked about that part, either. I was just happy he had the money to buy our building.

The vintage red brick building was a bargain back then, and Ken bought a few others in what were then rough neighborhoods of San Diego, near City Heights, a compact area for miles east of Balboa Park stuffed with refugees, immigrants, and Section 8 housing; 82 languages and 168 dilects were spoken within the mile and a half radius of City Heights, a hub of sex trafficking and cheap methampetamine distribution. Ken emphasized that the worst region of San Diego was nothing compared to his New York neighborhood in the 50’s, and I never argued with Cranky Ken.

“This place will look like Central Park one day,” he cranked out another morning, waving his log of an arm towards the park’s lush forests, a rarity in Southern California’s arid desert. Had it not been for decades of irrigation and care, Balboa Park would like more like the rolling rocky hills of Afghanistan than Central Park; recent water restrictions were choking the Magnolia we both loved.

“People here don’t know how fucking lucky they are to have a tree like that. Look at those kids climbing it,” he said with a dismissive gesture of his sausage fingers. “Chinks, spics, negros, and wops, fags and queers: they all climb that tree now. A lot of Mexicans bring their kids here, too. It’s fucking beautiful. They don’t know how lucky they got it.”

His eyesight wasn’t good as it used to be, and I didn’t feel like telling Ken the hispanics and Asians were probably nannies of the mostly caucasian kids who climbed the tree; Banker’s Hill was named Banker’s hill for a reason. The dark complexions weren’t the immigrants of Ken’s immigration, people just off the boat who shared stevedoring work with people who grew up in old-school New York, like Ken had. Unlike the displaced trees, displaced tech workers seemed to thrive in Southern California.

Many dark-skinned immigrants in San Diego were Indian software engineers, brought over by Qualcomm on work visas that made them wealthy by India’s standards but at around half the salary of local engineers from the UCSD Jacob Irvin School of Engineering, ironically created by the founder of Qualcomm; almost every cell phone in the world used a Qualcomm chip, and the company did well. They sponsored Qualcomm Stadium, the area in Mission Valley that held concerts, sporting events, and, once a year, the LSU alumni association crawfish boil, when a fleet of 18 wheeler trucks brought crawfish from Louisiana and fed 36,000 people, the largest crawfish boil in America outside of Louisiana. Agriculture land disappeared every day to make way for tech and biotech companies, and immigration changed to bring in guys with laptops instead of shovels.

I was unsure how Ken differentiated between spics and Mexicans, but San Diego’s population was around 42% hispanic and overwhelmingly from Mexico, especially with the border only a flat 16 mile bike ride away, or a quick trip from downtown via the Red Line. Downtown was down the hill from our building, a steep hill lined with more and more high-rises every year.

As for queers, at the other end of Banker’s Hill was Hillcrest, America’s second largest gay and transgender community and home of the world’s largest rainbow flag, perched above a brewery with beers named “Thick and Stout,” “Pearl Necklace Pale Ale,” and a Sunday brunch with bottomless mimosas that took on a whole new meaning when bartenders wore ass-less leather chaps. John says Hoover would have loved Hillcrest.

Cranky Ken had the vernacular of his generation, but he was fair. The median income in City Heights for a family of four was $24,000 per year, almost half of the annual interest rate on a two bedroom condo in Balboa Park thanks to the remarkably low interest rate in the 2010’s, less than 4% compared to the 13% or so I recalled growing up. To live, many families joined forces and crammed themselves into Section 8 housing, which could get them evicted if they had a landloard worried about losing their government subsidies; fortunately, Ken, to use his words, “couldn’t give a rat’s ass about the government or subsidies.”

I was in front of enough college kids every day to know that the lexicon of Ken’s generation was frowned upon now, but those kids don’t see the intentions behind crusty exteriors. Ken was a product of his generation and used adjectives considered racist or bigoted today. Hoffa, whom I believe was a decent person who did more to empower the working class – black, white, brown, or whatever – more than practically any government program, wrote in his first autobiography that my grandfather raped a Negro girl, as if a detail more than simply “rape” or “girl” was necessary.

Everyone seemed to use words back then considered offensive today. Chief Justice Earl Warren described the man Hoffa allegedly asked my grandfather to bribe, a Negro man, as if that affected the verdict. Hoover called Martin Luther King Junior “the most dangerous Negro” in America, believing that America’s social harmony depended on keeping African Americans low in social hierarchy.

Bobby Kennedy, notoriously at odds with Hoover after President Kennedy made his young little brother Hoover’s boss, followed his brother’s cries for racial justice, but held open disdain for homosexuality and called Hoover a “cocksucker” and a list of jaunts that would cause outrage today, yet empower the young political aspires among his agreeing peers.

Adjectives seemed to mean a lot to Ken’s generation, which many caucasian men his age dubbed the greatest generation. That generation also fought as hard as southern soldiers in the civil war to keep African Americans from sharing swimming pools with them. Arkansas governor Orval Faubus called their national guard to stop a 15 year old African American girl from attending Little Rock High school, and Alabama governor George Wallace, a WWII vet honorably discharged, did the same thing to stop a young African American lady from attending The University of Alabama after she was accepted based on merit.

Even the 82nd Airborne, which was formed in 1942 by the greatest generation and said to represent All Americans, didn’t allow African Americans; those volunteers went into the famed 555 “Tripple Nickle” paratrooper unit and performed so well against Nazi facism that American commanders fought to get the military integrated almost two decades before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 barely squeaked through congress, when enough of the greatest generation had passed and new ideas championed by people like President Kennedy finally got traction.

Kennedy, known as “the father of special forces” and the namesake of the Kennedy Special Warfare center, tried to keep Vietnam in check with small teams of diverse and highly trained soldiers who immersed and understood local cultures rather than judging them, saying that was a higher road than sending large numbers of undisciplined soldiers to use expensive military weapons from what President Eisenhower warned was the “military industrial complex.” Look where that got him. It’s no wonder Bobby spoke more harshly and wanted to wield a bigger stick; of course, that swing led to Bobby being shot and killed in 1968 by the redundantly named Sirhan Sirhan in response to Ameica’s support of Israel and the six-day war.

People Ken’s age had lived through all of that, and I absorbed his stories like a sponge, especially because understanding the 1960’s helped me understand my grandfather’s time period more than books or films, especially those from the northeast. They spoke a blunt truthfulness – their version of the truth – that simplified getting to know them and read between the lines of what they said.

Cranky Ken had alert pitbull eyes with a tenacious focus when he talked, and he had a permanent frown framed by disproportionately large jowls that somehow held their shape whenever he blew up and ranted about something that upset him. He was the type of person most people didn’t want to start a long conversation with, and you definitely never corrected his view of the world, unless you wanted to hear what a 15,000 pound bomb sounds like. When he learned that I was leading a course on entrepreneurship, he scoffed and said I should tell those “rich college kids” that I lived in a building owned by someone without a degree.

He was sincere, and he had a point that I used in class, but if you didn’t know Ken you could assume he was being mean. To him, and a lot of his generation that looked up to the uneducated but immensely powerful Hoffa, they viewed the privledged Kennedy’s with scorn, especially Bobby, who bore the brunt of Hoffa’s rage because of his Harvard law degree and President Kennedy’s nepotism for appointing him to America’s highest legal position when Bobby was only 35 years old. In a way, the Blood Feud between Hoffa and Bobby was working class versus elite, or what Marx called the proletariat versus the bourgeoisie.

Every time Ken saw one of my books about the Kennedys that called them Camelot or America’s Royal Family, he scoffed and agreed with Hoffa that Bobby was “a snot nosed little brat,” and pointed out a few instances of the smaller but tougher Hoffa leaping across a stage and putting his fist in Bobby’s face, making the notoriously hot-headed and bullying Bobby back down in front of witnesses and deepening his hatred of Hoffa.

Though history paints Bobby Kennedy and President Kennedy as being universally adored, many people felt the way Hoffa did, especially those who favored the communist-hunting days of McCarthyism and feared social change, mostly middle aged white males. One of the main reasons Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas was that so many right-wing people there were so openly toxic in their disdain of Kennedy and what they viewed as his socialist, “nigger loving” polices that it was easier to find patsies; in some photos that made the news, southern members of the State’s Rights Party lynched effigies of Bobby and Hoover (who was blatantly racist and said society was better if they didn’t vote and were tamed, but he followed the orders of his boss, Bobby, and seemed to be pro civil rights in the media). If you picked the right town, it was less about orchestrating Kennedy’s murder than facilitating it.

Coincidentally, Ken looked like Chuckie O’Brien, Hoffa’s adopted son of sorts. From what I read and heard, their relationship was more like a man empowering a young and loyal fatherless kid than a father caring for a son, but there’s no doubt they were close. Ken looked like Chuckie, but I sensed his personality was more like Hoffa’s. When he spoke, I tried to lean in and listen to layers behind the words he used.

Ken and Chuckie were the same age and the result of similar upbringings, and both had muscles under layers of age that hinted at growing up boxing in rough neighborhoods. Chuckie’s mom did accounting for the Chicago mafia, which is how most historians believe Hoffa started his connections. I never met him, but if he was anything like Ken, I think I’d trust him, and if I were in a tough situation, I’d choose Ken or Chuckie to be in my corner over any one of the waterlogged twats on SEAL Team 6.

Chuckie proved his tenacity in Hoffa’s 1964 jury tampering trial in Nashville, the one where Big Daddy was the surprise witness who sent Hoffa to prison. At the trial, Chuckie was sitting near Big Daddy when a gunman walked in the courtroom and pointed a pistol at Hoffa. Before security officers, Hoffa’s bodyguards, or the federal marshals hidden in rows of the open courtroom could react, Chuckie leaped across his bench and tackled the gunman. He landed a fury of punches, ripped the gun from the larger man’s hand, and pistol-whipped him with it; the irony was that everyone except security guards had been checked for weapons before court began. It happened so quickly that the would-be assassin was bloody and senseless by the time security guards could pry Chuckie off of him.

It turned out that the pistol was a pellet gun, but no one knew that at first, and after seeing the government-trained twats fail to do their jobs, Chuckie began patrolling the hallways with a .410 shotgun, staying awake and focused on protecting his idol and father-figure. Not even the Teamster bodyguards loyal to Hoffa had Chuckie’s love of what he called “the old man,” and that love is what hurled him between Hoffa and the gunman. Without knowing that, someone back then may have glanced at Chuckie and dismissed him as a nothing more than Hoffa’s gopher, which probably worked to Chuckie’s advantage when he took someone by surprise.

He would have done anything for Hoffa. Sure, SEAL Team 6 can take out Osama Bin Laden in a midnight raid, but they had the support of President Obama’s direct phone line, a few hundred thousand soldiers and spies, and a fleet of stealth helicopters piloted by a team just as disciplined as any ground force I’ve ever known (though, pridefully, I point out the old infantry addage that if you’re not infantry you’re supporting infantry; feet on the ground took out Osama Bin Laden and Hitler’s nest, and the most expensive bunker-busting bombs and Spectre gunships of the first Gulf war still relied on my team going deep inside a bunker before we took Khamnisiya). Chuckie’s small feet on the ground had puny .410 shotgun, a bird and rat hunting gun of the same shot strength as the .28 gage that, years later, Vice-President Dick Cheney would use when he made national news when he was was duck hunting and shot his 78-year-old friend in the face, doing no more harm than making Cheney the butt of comedy shows and turning Dick the Duck Hunter an internet meme. In President Bush Junior’s memoir, the surprisingly witty Texan and supporter of large-scale military actions wrote that every time Cheney walked into the oval office, the staff shouted, “Duck!”

Cheney, a wrestler in high school and college, may have made it into the National Wrestling Hall of Fame, but he’ll never be revered marksman. He was almost as innacurate as Lee Harvey Oswald. Chuckie wasn’t a good shot either, which is probably why he chose a shotgun. But even without a shotgun he proved he’d tackle an armed man twice his size and beat him bloody with the man’s own gun.

I can only imagine what Chuckie thought when Big Daddy stood up and sent Hoffa to prison, but I have an idea, because almost 60 years later, even leading up to when he passed away in 2020, on his deathbed Chuckie was still telling people:

“Fucking Partin. I should have killed him when I had the chance.”

Chuckie stood below Big Daddy’s nipples, yet he was unintimidated by a big and brutal man who terrified everyone else in Hoffa’s circle. He spoke of mafia loyalty to anyone regardless of race or religion, just as long as they were part of the family. Like Ken, Chuckie defined family ambiguously, if at all, but he was loyal to it and as fierce as a pitbull.

Instead of a team of SEALs and a fleet of stealth helicopters, I’d gladly ask Chuckie or Ken to be in my corner any day.

I was leaning back in my chair with my feet on the balcony, rubbing my neck and lost in thought; I didn’t know what I’d do in Cuba, or what I’d expect to find that almost 60 years of investigations by the FBI, CIA, reporters, and hobbyists had overlooked. John exhaled smoke from his Marlboro and pointed to my shoes dangling over the railing and said, “Dude, you have huge feet.”

I looked at him and held up my big hands and said, “You know what they say about people with big hands and big feet…”

I waited until a couple of the guys smiled, then I softened my voice and said, “It’s hard to find gloves and shoes that fit.”

Our laughter dimmed the dining rom din for a few brief moments, but was silenced by a siren sounding and blue and red lights dancing across the maroon brick balcony. An ambulance rushed past us on the way up from the way downtown, illuminating the otherwise dark view across Balboa Park. The doppler effect warbled as it passed us, and the the ambulance disappeared up 6th Avenue, probably on its way up the road to Scripps Memorial Hospital. In the relative silence and darkness from loosing our night vision, someone popped open the cooler. Ice rumbled and they fished out a round of fresh Tecates and Abita Ambers. I reluctantly declined. Carleton crunched his empty Tecate can under the sole of his loafers, which had a metal plate with a bottle opener built into the bottoms, and accepted an Abita.

“I don’t have much of a plan,” I said to Levi. “The part about my grandfather popped up last minute. I’m mostly going there to scuba dive and rock climb. I’m meeting an old friend and few guys I met in the Himalayas last year, and I’m meeting a friend in the state department to catch up and talk about Guantanamo. I’ll probably listen to what he has to say about the Bay of Pigs fiasco, and then go from there.”

Erin, a lady more comfortable with Tecates and Marlboros than the wine and California charcuterie laid out on the dining room table, exhaled and said, “Of course you have a friend in the state department.”

I shrugged and said, “A lot of my buddies stayed in the service. The natural evolution was some type of special ops and then secret service. I don’t really know what he does, but he hobnobs with presidents and religious leaders and shit like that. He’s still just a dude, though. I’d like to ask if any new records popped up.”

Almost all of Big Daddy’s criminal records vanished like a tiny red handkerchief from a magicians hand. Why, if not how, was summarized by Chief Justice Earl Warren in 1966’s Hoffa versus the United States, where he described why Big Daddy would want to testify against Hoffa. He wrote:

“A motive for his doing this is immediately apparent — namely, his strong desire to work his way out of jail and out of his various legal entanglements with the State and Federal Governments. And it is interesting to note that, if this was his motive, he has been uniquely successful in satisfying it. In the four years since he first volunteered to be an informer against Hoffa he has not been prosecuted on any of the serious federal charges for which he was at that time jailed, and the state charges have apparently vanished into thin air.“

Not all had disappeared. In 2004, the year Hurricane Katrina swallowed New Olreans and countless things were lost and fourteen years after Big Daddy’s funeral, a small blip in national news attracted attention: a team of men dressed in black, like the film series Men in Black, walked into the Baton Rouge police station and removed all records from Big Daddy’s 48 hour stay in jail back in 1962, including the testimony of his cellmate, Teamster Sydney Simpson, and CIA pilot Barry Seal, who was based in Baton Rouge. The news was overshadowed by Katrina and by another Baton Rouge tidbit that made the late-night comedy circuit: one of our fire stations burned down when firefighters responded to a call and left a propane burner burning inside that was frying a 15 pound turkey in a 20 gallon pot of vegetable oil. (Anyone frying a turkey should know that you use peanut oil, not vegetable oil, because has a higher flash point.) Thanks to late night comedians, I was alerted to the news. Most people said my home town police and firefighters being lampooned on national media, but a few of us kew why the records mattered so much in 1962, and pondered why they were of interest in 2004.

Big Daddy and 26 year old Sydney Simpson were arrested for kidnapping Simpson’s two and six year old children, and then they were also charged manslaughter in Mississippi. Big Daddy faced life in prison, called the New Orleans FBI office, and was released. Simpson stayed in, and his testimony was taken and used by Hoffa’s lawyers in an unsuccessful attempt to discredit Big Daddy. According to Warren in Hoffa versus The United States, Simpson went on record as saying:

“A few days later, Partin was released from the jail. From the day when I first saw the deputy until the date when Partin was released, Partin was out of the cell most of the day and sometimes part of the night. On one occasion, Partin returned to the cell and said, ‘It will take a few more days and we will have things straightened out, but don’t worry.’ Partin was taken in and out of the cell frequently each day. Partin told me during this time that he was working with Daniels and the FBI to frame Hoffa. On one occasion, I asked Partin if he knew enough about Hoffa to be of any help to Daniels and the FBI, and Partin said, ‘It doesn’t make any difference. If I don’t know it, I can fix it up.'”

“While we were in the cell, I asked Partin why he was doing this to Hoffa. Partin replied: ‘What difference does it make? I ‘m thinking about myself. Aren’t you thinking about yourself? I don’t give a damn about Hoffa. . . .'”

Despite evidence like that, the jury was so enamored by Big Daddy’s charm that they only deliberated four hours before accepting his word that Hoffa suggested he bribe a juror in the Test Fleet Case with $20,000 from Hoffa’s hotel room safe. Two years later, the only supreme court justice to dissent against using Big Daddy’s testimony was Earl Warren, and Hoffa went to prison based on Big Daddy’s word.

A lot of Hoffa’s defense wasn’t allowed to be used, like records from Cuban generals under Castro thanking Big Daddy for training them. Those records were taken, along with some evidence of Barry Seal, the CIA pilot based in Baton Rouge, yet the men in black didn’t leave receipts and no federal agency claimed responsibility and the records haven’t been seen since.

Perhaps coincidentally, 2004 was the year Frank “The Irishman” Sheenan published his memoir, “I Heard You Paint Houses,” where he claims to have painted a Detroit house red with Hoffa’s blood; in the memoir, he intentionally slipped in pieces of the puzzle to what happened to President Kennedy, and inadvertently gave me clues to Big Daddy’s relationship with President Nixon and Audie Murphy. Martin Scorcesese instantly snapped up the film rights, and raised $257 Million to make an epic entertainment film that was coming out later the summer of 2019. For all anyone knows, Scorcese’s team may have dressed like men in black to get the records from Baton Rouge’s jail. I had only read the book once, around the time it came out, and I planned to reread it on my flight to Cuba and see if other pieces of the puzzle I knew now fit better with hindsight.

“After 9/11,” I said, “my buddies bounced around all the new three-letter organizations. We’re all still friends and meet up whenever we can. I haven’t seen this guy in a few years, but we’re still tight.”

“It’s like hanging out with y’all,” I added.

Levi and Carleton raised their cans as a toast. I raised an imaginary glass and caught eye contact; they rotated their heads and locked eyes with Erin and John before everyone sipped.

John lit another cigarette from the butt of his last one. I don’t know how he does it. He’s a big guy, around 6’2″ and 240 pounds, and he works almost 70 hours a week as a civil engineer with a desk job, but he can out-cycle me when we ride 16 miles to the Tijuana border and back for beer and tacos, and out-paddle me in any type of surf. He never had biologic children, but he adopted his wife’s two kids long ago and now they were empty-nesters. Her loud laughter from the dining room would pierce our balcony now and then; she hated when he smoked, which happened after a his first six-pack of Tecate was crushed for recycling and he broke out a backup 12-pack that he kept stashed in the wheelbed of his truck. I had known them since their kids were pre-teens. Now they were old enough to join us in a bar now and then, and they’d ask us questions typical of their generation like, “Who was Jimmy Hoffa?”

I looked at Erin and said, “You’d like my buddy. He reads a lot.”

I smirked and added, “And he’s into kinky shit.”

She smiled whimsically and raised a beer; we caught eye contact and she sipped without breaking her gaze.

John snickered and said, “Erin wants to know his shoe size.”

She didn’t deny it.

I told Levi, “My visa makes me use local businesses, nothing owned by the state, so I’ll probably just start up conversations and see what happens. And I’m meeting a few guys there to go a climbing in a small town a couple of hours from Havana. They’re on a journalism visa for what they call eco or adventure travel, but they want to get some politics through the Cuban editors about healthcare.”

Blank stares. John’s eyes were closed, and he giggled as he dragged on his cigarette. I paused to see if he’d share the joke, but it rattled around inside his head without spilling into conversation.

“We’ll climb in a tobacco growing region with old-school guys,” I said. “Vin-yal-es or something like that.”

Despite living in San Diego for a long time and in Central America for a year and a half, my Spanish was, and is, muy malo. For someone who was, according to the U.S. government, a supposed “communications liaison” in the 1990’s, I was notoriously bad among my peers at pronouncing foreign words. I relied more on tones, hand gestures. and drawing things in the sand than dictionaries. Today, I’d just use a translation app if I needed to communicate basics. Deeper conversations always come from nuances, and as a point of pride or self growth or whatever you could call it, I hoped to improve my Spanish by turning my phone off and not using apps, getting away from tourist zones for a few weeks and immersing with people so we could build trust before I asked questions. If I had a plan, that was it.

“It’s a valley with limestone cliffs a couple of hours from Havana,” I added, “Fertile ground for farming. Fidel gave up smoking, but kept the cigar in his mouth out of habit or for the image. He visited the farms for fun and photo ops, like any president rolling up his sleeves and visiting American farmers.”

I stretched my arms above my head and and felt crepitus in my shoulders from old rock climbing injuries and parachute crashes, and said, “He deemed rock climbing as an unnecessary risk, so it’s illegal, but he loved diving and set up dive centers all around the island, which brought in most active tourists. There’s not much tourism in Vin-yal-es, and the valley’s still old-school. Maybe someone will remember seeing my grandfather: he was remarkable looking.”

John’s guffawed and said, “Partin’s going to find all of the 70 year old Cubans with blue eyes who look like him, and go from there.”

John’s one of a few people know Big Daddy had sky blue eyes and strawberry blonde hair. Most photos of him in his prime are in black and white, and by the time people were used to color photos he had gray hair, and the poor quality of developing back then blurred his blue eyes to seem a dull grey-blue. In his prime, Big Daddy was one of the most classically handsome people you’d ever see, a smiling man who was tall, blonde, blue eyed, broad shouldered, and who had a narrow waist. He had a classic aryan look that Hitler would have adored, which was part of why John said Hoover was enamored with him.

I have Mamma Jean and my dad’s dark brown eyes, and I used to have auburn hair with streaks of red and no clear lineage of that. After a late night of drinking, I told John about all of the blue-eyed people in Baton Rouge, Woodville, and Flagstaff who probably didn’t know they were my cousins, and that when I was in high school and LSU I avoided dating blue-eyed girls, especially tall ones. I hadn’t considered that anywhere he went Big Daddy probably caught the eye of local ladies, so maybe John was on to something. I wondered how many blue-eyed Cubans were my dad’s age.

“Hey Levi,” John said. “If you’re Fidel Castro, what’s your safe word?”

“You mean Raul now.” Levi said.

John said, “Yeah, whatever. What’s the safe word for a Cuban dictator?”

“Free market,” Carleton suggested.

“Hurricane,” Erin said.

“Rough Rider,” I said, and John instantly countered: “Dude, that would just make him harder than Chinese calculus!”

We erupted into laughter.

When we calmed down, Levi said with foresight two steps ahead of John, “How about ‘Harder?”

“Dude!” John exclaimed. “Harder? That’s the worse safe word ever!”

We were chuckling and I said, “Yeah, like making it ‘Deeper’ or something like that.”

“What about Hoover’s safe word?” Levi asked.

“Easy,” Erin said. She waved across Levi’s puffy curled hair. “‘Communist’ would make him softer than Levi’s mop top.”

She stole my punchline, but I was glad someone said it. When the laughter died down, I said, “I was thinking of using the climbing trip to write a memoir, sort of like Wild.”

“I loved that movie!” Erin said in her high-pitched voice. She calmed down and said, “And the book. I always wanted to hike the Appalachian Trail.”

Erin took a deep drag and exhaled smoke up towards the stars and said, “Why don’t you do it? You’re The Most Interesting Man in The World. Write about one of your trips.” She was a bit drunk, so I smiled and nodded and didn’t tell her she that’s what I had just said.

Erin spent her ample vacation time traveling the world with focused itineraries she posted on Facebook before she left home, a sort of travel blog that was more about planning than reporting. When home, she hosted dinner parties with themes from whatever country she had visited, and she also hosted a huge block party and multi-cultural pot-luck after every year’s Pride parade, the one that passed my balcony and followed the equally sized but much more tame St. Paddy parade. She was the unofficial mayor of Hillcrest, catering to all types of people, though she dreamed of retiring to a more relaxed pace of life and setting up her own architectural firm on some Carribbean island – any one, just as long as they had beer and ships full of sailors coming into port every few weeks. I don’t think she had a safe word.

Despite her diet and smoking, Erin was an avid hiker. Like a lot of us who lived near Balboa Park, she lived and worked in Hillcrest, in part, so she could quickly immerse in nature and huff and puff Balboa’s five miles, a forested oasis in an otherwise concrete jungle. She hoped to meet a man who wanted to settle down. I joked that she was in the wrong neighborhood and attended the wrong parties. Her Pride party brought in a hundred gay guys in better shape than any of us – a commedian in the 1990’s said he didn’t want to be gay, but he wanted to be in gay shape, because apparently it took a lot of muscle to suck dick (gay competition was fierce and somewhat superficial, and without kids many had time to frequent gyms). At my parties, most of my friends were happily married and of no interest to singles of any persuasion. In Hillcrest, the biggest compliment Erin would get was from cross dressing men who liked her shoes; when we were together, those same men would comment on my shoe size and seem disappointed that I didn’t banter with them about it.

Erin dropped her cigarette into a Sierra Nevada bottle half full of luke-warm beer and cigarette butts. It sizzled and extinguished. The smell waifed out and made me slightly nauseous – it’s funny how you notice those things when you’re not drinking heavily but your friends still are. John put his out and lit another. Erin’s a finger width shorter than John, a bit heavier than average, and can out-swim me. I don’t get it.

Erin fished another beer from the cooler and asked me, “Who was that guy playing your grandfather in the new Scorcese movie? The one who called you when they were filming?”

“Craig Vincent,” I said.

Blank stares.

“Remember Casino?” I asked.

Most people nodded or grunted yes. Carleton said: “Casio was a 1995 Martin Scorcese about Las Vegas, starring Al Pacino and Joe Pesci.” There were a couple of “oh, yeah”‘s. Levi looked at Carleton and asked something about how he knew so much about older movies; John chirped in and said those weren’t old movies, because we all remember seeing them, which garnered a restrained laugh from everyone but Carleton who viewed them as “classics.”

He was a film buff. Carleton and Linda were DINKS, Dual Income No Kids, about 15 to 20 years younger than the average age of our group on the balcony. They had just enough overlap to remember things like phones hooked to your wall with a cord, but they grew up with the internet and learning to find information and entertainment rather than waiting for it to come to theaters. I sometimes went to parties in their condo, where hipsters their age commented on my tendency to wear Cuban boleros from local thrift stores and collect used vinyl by quipping that I was an O.G., an Original Gangster, and therefore an honorary 30-something year old hipster. I didn’t argue with them.

A few times over the years Carleton and I stayed up late, passing glass bowls of weed back and forth in the predawn hours when Cranky Ken walked by to get quarters, ken would stop outside the balcony and chat us about old gangster movies. He didn’t care what people smoked or drank as long as they paid rent and he didn’t hear from them. He liked us, and Carleton joked that my rent was a song and occasional story. There’s probably truth to that, but Ken’s affinity for me is mostly because I’m handy with a Leatherman tool, and after I moved in neighbors stopped calling him to fix small things.

Cranky Ken was an unabashed fan of Hoffa and the history of his Blood Feud with the Kennedys, but he was remarkably timid when asking me what I remembered. When I share a story, it’s the only time he refrains from offering his opinion; the closest thing I’ve heard him offer as an opinion about my grandfather is that Brian Dennehy did a good job portraying him in 1983’s Blood Feud, and that they looked a lot alike.

Big Daddy was handsome and blonde and blue eyed, and his personality made a lasting impact. It’s likely that someone in Cuba, which was overwhelmingly brown skinned and with brown eyes, would remember seeing him. I didn’t have a plan other than to meet people who would have been Carleton’s age in the 1960’s, when my grandfather was in Cuba, and go from there.

I said: “Craig was the big dude in a cowboy hat that Joe Pesci reached up and slapped because Pacino told him to.” Joe Pesci was an actor who fit Chuckie O’Brian’s stereotype, and over the decades he had earned a fine livelihood films portraying squat pitbulls loyal to a boss, and the scene in Casio epitomized that dynamic.

John chipped in, “Did he slap him and say, ‘who’s your big daddy now!'”

When I stopped laughing enough, I wiped both eyes and said, “I have a theory. About The Godfather. I started thinking about it after Craig and I talked.”

“I reread a book by some mafia guy,” I said. “At one of the used book shops in North Park. I can’t recall his name – but he was the confidential advisor to Scorcese on The Godfather.”

“That was Francis Ford Coppula,” Carleton interjected. “Not even on the same scale.”

“Thanks,” I said. “Coppula. Anyway, the guy was in the mob and worked with writers to make the film authentic. He wrote something that stuck in my mind. It was off-hand, as if even he didn’t get it.”

My hand made a gesture as if holding something briefly, then tossing it over the balcony, and I said, “He was an intermediary between Coppula and the mafia. They wanted to be anonymous, but they wanted the film to show them as families more than gangsters,” I paused, rambling my words because I had not having articulated the idea out loud yet, and the words that spilled out were: “I think they asked him to put in the horse head scene as a warning to Hoffa and the Teamsters.”

I glanced around and saw blank stares on every face except Carleton’s. He misunderstood the blank stares, and said, “There was a scene where a Hollywood film producer woke up with his race horse’s bloody head on his bed.”

Everyone grumbled that they knew that, but didn’t see the point. I said, “Hoffa used to fund Hollywood films with the Teamsters Pension fund.” I paused for effect and then said, “It was around a billion dollars back then. I think it was $1.1 Billion by 1962.”

Carleton and Erin looked up as if calculating that in today’s cash; they looked back down and seemed impressed.

“He also lent it to the families to build Vegas casinos and New Orleans hotels.” I said. “But Coppula would have known about Hollywood and seen The Teamsters logo across the final screen of credits. The logo was two horses, Thunder and Lightening, from when the Teamsters drove horse waggons. They’re behind a huge, blue, ship’s steering wheel,” – my head cocked and I paused a brief moment – “or dharma wheel. It’s impossible to miss,” I nodded towards Carleton, “if you sit through all the film credits.”

“Hoffa was in jail then,” I said, on a roll, leaning forward and speaking faster usual, “and he was negotiating with Nixon for a pardon. He may have offered information, and I think the families were telling Hoffa that his power was through with them and Hollywood, and they were warning him to keep his mouth shut around Nixon.”

I inhaled and puckered my lips to say, “B’…,” but John’s face began to crinkle with expectation; I leaned back and slowed down and said, “…My grandfather wasn’t changing his testimony, and Life magazine showcased him against the mafia just as The Godfather was being written, saying the mafia was trying to bribe him on behalf of Hoffa.”

“Media twats dismissed it,” I said. “They said the mob didn’t bribe. But they probably didn’t read the details of why Hoffa was in jail before flapping their lips. It’s no different than today. When the mob didn’t change my grandfather’s mind, I think the families were worried Hoffa would talk when he got out, so they had Coppula add the horse head scene to send him a message.”

For the first time that evening – and in general – John had nothing to say. Levi was looking up thoughtfully, and when he smiled I knew he connected the dots and saw a bigger picture. Even Carleton looked like he had learned something. Erin’s gaze was on me, and she was smiling as she sipped her Tecate. Levi smirked and fished around the cooler for a bottle of Sierra Nevada. Everyone refilled or relit. My mind wandered.

Beyond Levi’s shoulder, under the dim yellow light of a square, Spanish tiled public restroom across the street, I saw Mr. Charles bedding down for the night beside the men’s door. The year before, after sharing some red beans and rice and a pre-rolled joint from a nearby dispensary, I taught Mr. Charles how to pick the 1950’s-era lock and gave him one of my older pick kits. That year, downtown San Diego had an outbreak of Hepititus that slowed tourism and made national news, because it was attributed to the roughly 6,500 homeless people around downtown and Balboa Park, and public outrage reacted and demanded that police lock the bathrooms, compounding the problem.

Giving Mr. Charles access to a bathroom after the mayor locked it was the least I could do for him and my neighbors. A few of my friends knew I fed homeless red beans and rice to people in Balboa, but none knew I taught them how to break into bathrooms. Erin said that I was a “nice guy” for helping them, but if that were true, Mr. Charles would be on the balcony sipping beer with us, or in the dining room, nibbling on some California charcuterie, commenting on its vegetarian, vegan, and gluten free options, and chatting with everyone about what makes something organic, or asking what they did for work. Instead, he was bedding down on the ground beside a public bathroom less than 20 yards away.

After some parties, I dodged cars on 6th Avenue and brought him leftovers and a joint every now and then. To not make it like charity, I told him the bag of weed was a gift from Uncle Sam; local dispensaries offered a discount for disabled veterans, and the VA recently assigned me a 70% rating. I received half off campsites in national parks, $1,317 a month to blow in a city where rent on a one-bedroom hovered around $2,000, and 25% off weed, an irony because my dad went to prison for growing it during Reagan’s war on drugs, and weed was still illegal federally and in 26 other states for reasons I didn’t understand. Mr. Charles had never served, and he no disability to fall back on, but he said that okay; one of my tattoos says, “Everything’s a choice,” and Mr. Charles agreed with it.

I was lucky, he said, and so was he. He could choose to work any longer without being beaten into submission, unlike in many countries including the soldiers I fought in Iraq. His body probably hurt as badly as mine from his decades of unskilled manual labor, probably landscaping or some other job now dominated by Hispanic immigrants, yet he never complained. He viewed Balboa Park as a free campground that was an better deal than my half off at national parks.

I told him he was better off than I was, because I still had to pay for weed, but he got it delivered to him for free. That made him laugh, and Carleton kept telling me that things like that were what Mr. Charles saw, not that I never invited him over. I knew that, but knowing isn’t as deep as believing or understanding.

On the other side of the building from Mr. Charles, Miss Mary was bedding down beside the lady’s room, barking something to people who weren’t there. I don’t know her story, but for almost two years she had never complained about life to me, which is more than I could say for most of my neighbors nibbling on California charcuterie in the dining room, a spread lined with fresh local avocados sprinkled with pink Himalayan salt and with choices of slices from a local all-grain sourdough miche or organic gluten-free crackers, cheese from free-range cows on east county dairy farms, and a range of locally cured meats I couldn’t pronounce made by bearded men wielding Damascus steel meat cleavers at the Hillcrest farmer’s market. Though I never heard Miss Mary thank anyone, I never heard her complain. They were both old enough to remember not being allowed to ride on public buses with white people; had more people spoken like Ken back then, I believe the world would be a better place for Mr. Charles and Miss Mary.

Behind the building, facing away from 6th avenue and towards the irrigated forests of Balboa Park, two jittery transients I didn’t recognize were collecting newspapers and cardboard for a bed. I couldn’t hear what Mary was mumbling over the laughter bubbling from my living room, but she seemed upset at whatever she saw in her mind’s eye. Like with Ken, I avoided long conversations with Mary. The transients attracted my attention because I was worried about her; the rate of rape among female homeless people implies that talking to invisible people doesn’t make undesirable enough to avoid. I usually kept my distance from her, and gave Mr. Charles extra rice and beans or leftovers from parties in case she calmed down and was hungry. I gave Mr. Charles one of my Benchmade folding knives with a pocket clip for fast access and a fancy locking mechanism that could apparently withstand a hammer strike without closing the blade.

Levi broke my train of thoughts by asking: “Hey J, can I see your knife?”

I leaned to my left and slid the orange rescue Leatheran tool clipped inside the right pocket of my blue jeans, and handed it over with the carabinner and bottle opener side facing Levi. Leatherman’s patents on a folding plier and knife combination had long since expired, and they, like most outdoor oriented companies, seemed to innovate by adding bottle openers to everything they sold. He took it and popped his cap and tossed the Leatherman back to me. I returned it and adjusted a thumb tip with a small red handkerchief that I had put in my pocket earlier that day, one of the simple flesh-colored ones available at all magic shops that can hide a small handkerchief inside. There were bottle openers everyone, but Levi liked using my knife; it has a nice feel in his hand, which is much smaller than mine.

If it weren’t for Levi, I’d be the runt of our litter on the balcony. He’s a 5’4″ thin jewish guy from Santa Monica who can eat whatever he wants without gaining girth. With curly hair, thick designer glasses and an erudite demeanor, he looks like Malcom Gladwell, or like Seth Godin wearing a floppy afro wig. His personality matches Malcom and Seth, the type of guy who carries a thesauruses into a dive bar and has a brain full of facts about everything on the table. He graduated from UCSD in software engineering and began to focus on the then-nascent concept of cyber security, and has been in San Diego since. He lives in one of the expensive suburbs, where his wife, a San Diego native an inch taller than him, stays at home and focuses on being there for the kids when they come home from school while he puts in extra hours. Levi’s also immune to hangovers, another super-power common among everyone in our group of friends except for me.

Levi handed the Leatherman back to me. I accepted it and said, “I still don’t get the point of Obama’s entrepreneurship visa. I read that Trump’s already dropped it from the loophole.”

I spun the Leatherman around my palm and flipped it over a few times with a flick of my fingers to show both sides. I caught it with the bottle opener side facing away from me, and held it up.

“I think in terms of innovation,” I said, lost in thought. “A lot of people think innovation is adding more gadgets,” I nodded towards the knife, “like a bottle opener, and that entrepreneurship is selling your gadget. But I’d like to get people thinking about solving problems, not depending on the government to do it for them. But apparently that’s not part of this term’s policy for Cuba; politics aside, if we could get more people solving their own problems, governments would have less control over them.”

“That’s what you do at USD, isn’t it?” Erin asked.

I shrugged. “Sort of. I’m more coaching teams that already have an idea and a prototype. We’re working with cross-disciplinary teams. I’m also an advisor at UCSD’s entrepreneurship program”

I nodded towards Levi and added, “USD just launched a new cyber-security program, and we’re linking physical products to it and getting kids to try innovating.”

“No one knows how to train for the unknown,” I said, “so we’re trying to get them focused on problem solving as a team rather than job training as an individual. It’s like with wrestling: be able to perform as an individual, but still work as a team. It’s a mindset that’s easier to accept the younger it begins.”

As if on que, a little girl’s voice from inside say, “Uncle J?”

I leaned forward and slid my feet off the balcony and stepped through the double French doors into the living room where a tired looking eight year old girl stood. I took a few steps towards her, tucked my Leatherman into my right jeans pocket and held on to my pockets with both hands as I kneeled down to her eye level; the larger motions covered my right thumb stealing the thumb tip packed with a small red silk from the small pocket of my jeans. To further distance my right hand from action, I used my left hand to rotate my baseball cap backwards, a habit she’d be used to because I did it whenever I stooped to her level, so that the brim wouldn’t poke her forehead when we spoke softly. I didn’t need the thumb tip; I could make a small silk vanish from my left hand by sneaking it out the gap between my two middle fingers, but most people needed a thumb tip, so I kept one handy for teaching magic.

I rested both hands on my left knee, a natural gesture that hid the tip tucked in my right hand, and smiled and said: “What’s up, sweetie?”

I have a nice smile. I inherited it from Big Daddy, and it’s nothing more than an effect of our high round cheeks and the muscles that pull up on the corners of our mouths. It makes me look like I’m smiling even when I’m not.

I also inherited his neck muscles, which are thick and make an almost perfect 45 degree angle from under our ears to our shoulders, giving anyone who glanced our way the impression we’re more muscular than reality. But Big Daddy had thick arms and wrists, adding to the impression he was massive, whereas I have thin wrists and forearms that, in contrast with my big hands, make me seem smaller and weaker than I am if you see me up close.

Big Daddy’s thick wrists helped him escape handcuffs and ropes; apparently, he was able to escape from jail without any training. I had spent years reading Houdini books on how to escape anything, and was briefly coached under The Amazing Randi when he was on his crusade to expose pseudo faith healers that were abundant in the south back then, but when people tightened handcuffs around my thin wrists I couldn’t get them to slide over my wide hands.

In escape routines, which were never my specialty, I learned to rotate my wrists sideways, the long axis, as if I were using my fists to leverage someone’s head down in a wrestling move, and I held them slightly apart without my face showing the effort it took; the gap was unnoticeable unless you were looking for it, and after ropes were tied with elaborate looking knots that became everyone’s focus, I could relax my arms and close the gap, then rotate my wrists and slide out. I never told John that I once practiced escaping from ropes, because I didn’t want to give him fuel for jokes about me living next to Hillcrest.

“Momma said you could tuck me in,” Hope said.

I saw Dana watching us from the corner of my eye. She was standing next to Linda and holding held the same can of Abita Amber that she’d probably been nursing for an hour or two. She had a smile that was softer and kinder than anything I could muster, not a resting smile or a genuine smile, but simply a smile that came from a source deep inside. She’s a finger width taller than I am, but doesn’t look it for some reason, and most people are surprised at how tall she is when we stand together. Dana looks younger than she is, too, appearing closer to Linda’s age than mine though she’s two years older than I am.

She’s thin and athletic looking, despite her only exercise after the army was hiking near her home in Topanga Canyon, mostly in Malibu State Park, and an occasional backpacking or easy rock climbing trip with me around Idylwild or Joshua Tree. She used to play beach volleyball, but stopped because it wasn’t as fun after she dropped out of college to pursue art full time, and after she had Hope her exercise leaned towards whatever they did to play together, which was plentiful. She worked in movie studios most days and doesn’t get a lot of sunshine, but looked tanned because her biologic father was, coincidentally, a jazz musician from New Orleans and 1/2 Creole. Her mother met him after he performed one night in 1971 at the then-new Baked Potato jazz club up the street from the Magic Castle, when Sanford and Son was still on television and Redd Fox was a regular there and Dana’s mom was into jazz and standup comedy who frequented the Potato. Except for four years in the army, where we met at Fort Bragg, she’s been near her mom and Hollywood ever since.

Hope is light skinned and has brown hair, close to the dark auburn hair forming lamb chops on my mostly grey beard, and when I visit Hollywood to perform and we walk around together, people assume we’re a family. We’re not. Dana and I separated in 2004 and divorced in 2005 because she wanted biologic children and I did not; after waiting ten years to see if either would change their mind, her biologic clock made the choice for her.

I kept my gaze on Hope and said of course. I stood up and pulled my jeans up and tucked the thumb tip back: it wasn’t the right moment. I lowered an open, now-empty hand, and Hope put her’s in mine and made a loose fist. Her hands were the size you’d expect for an eight year old girl, and I’m not tall, only 5’11” in the mornings (most people shrink around 1-2 cm by the end of the day because our intervertebral slowly discs compress under load and rehydrate overnight), but I inherited Partin-sized hands and feet that need XXL gloves and 14W shoes.

My loose fist swallowed her relatively tiny hand, which made her seem even more petite. I saw Dana beaming in my periphery, and my smile broadened. It really is a nice smile; Dana said it was the first thing she noticed about me when we met almost thirty years before, the first year I started shaving, when my beard would have been as maroon as my Airborne beret and as soft as Levi’s floppy hair.

Hope and I turned right into the doorway of my office and library. The futon couch was open and made for Dana, and a plush car-camping inflatable mattress was on the floor for Hope. She had put her weekend backpack beside her mattress when they arrived, nestling it near her shelf on the right side bookshelf.

The mattress nestled between two bookshelves that framed the new view of downtown, possible in the short time between when that old building was gone and the underground parking of a new high-rise was under construction. The bookshelves made the window look like a large television framed in an entertainment center. Through the window, I saw the lights of an airplane approaching for landing, and a moment later I heard the dull roar of breaking jet engines subtly rumbled through our walls. I stretched and moved my left arm into my periphery, cringing slightly at the grinding sensation. It was around 11pm, so that should be the last plane of the night.

After 11pm, the airport fined airlines $75,000 for landing, thanks to the people in Point Loma who bought during the 2000’s housing boom and woke up surprised that their multi-million dollar homes were in the flight path. Our condo, like most on Banker’s Hill, accepted a deal from the airport to replace all old windows with new noise-dampening ones, but the low rumble still made it through the brick building and subtly resonated in the older, original hollow wooden doors. I closed the black-out curtains and dimmed the lights, tucked Hope in, and sat cross-legged beside her mattress.

She tried to talk to me as she laid down, but she was too tired. She stopped talking and her eyes remained shut, and within two minutes her breathing was slower but still irregular. I’d wait until she was fully asleep before leaving.

Another airplane rumble rippled gently through the room. I straightened my posture and rested my hands on my thighs, and focused on breathing softly to help her fall asleep. Someone glancing in would have thought I was meditating; that wouldn’t be far from the truth, which was that I knew when my neck was hurting I was happier diverting my attention. I slowly moved my head as if bringing on ear to my shoulder, then back to the other side. The muscles were tight, and I had to strain a bit but still didn’t approach the flexibility I had as recently as seven years ago. I scanned my bookshelves to focus my attention on something – anything – else.

The bottom two shelves of the right-hand bookshelf were for Hope and Dana. The bottom shelf had a short row of books Hope had outgrown one the years, mostly ones typical of her age and with a bias towards princesses and fairies, and a few drawing pads and colored pencils that were timeless. The shelf above had what I thought or hoped she’d enjoy while I was in Cuba, books like the Harry Potter series and some science fiction series about a kid a few years older than her who had multiple universe versions of himself to help solve crimes. I bought them on impulse after the cute young lady who worked at a used bookshop in North Park recommended the series; I had told her I was shopping for an eight year girl old who read above her level, and with some form of science built in, like Ender’s Game and other classics of my generation. That reminded me about Ender’s Game, and I added a copy of it to the shelf. I put a couple of maker’s project books I already had at USD, and a maker’s kit that I had designed for anyone from around age ten to a freshman in college engineering; it had typical nuts-and-bolts and wires-and-circuits, and I added a few Arduinos and things it could make move, beep, light up, or roll, and a couple of Rasberry Pi’s that, if I had WiFi in the condo, could connect to the internet, part of the “internet of things” that college kids were calling it. I hoped Dana would help Hope with the online parts; neither had ever been interested in computers, but maybe a shared project would prime the pump and get them to learn together. We were a mile walk from the new downtown library overlooking the old ship-building docks, and it had ample computer rooms on the middle floors and a respectable maker’s lab on the sixth.

For Dana, I added a couple of the new Stephen King books that had already made their way to the used book shop. She’d have access to all of my home and books, but she liked popular fiction like Stephen King and a few other authors I can never recall. The lady at the bookshop recommended them based on Stephen King’s “The Stand” and his Gunslinger series, which he said all his books were leading up to and were not his typical horror stories. I had flipped through the books I bought for her, but I was so behind on other reading that I didn’t lean in.

The upper three shelves of that bookshelf were mine. The top shelf was mostly memorabilia, a small display of medals in a dark brown oak frame, and the Vietnam-era bayonet with a quarter-inch piece missing from the tip. I had used in the battle for Khamisiya, a relic when it was issued to me when I was first assigned to the 82nd Airborne as a body replacement, but it was the only one available in the scavenged armories leading up to the first Gulf war; as Rumsfeld would harshly say, sometimes you go to war with what you have, not what you want, though it turns out the thin double-edged Vietnam-era bayonettes were more practical in hand-to-hand combat than the thick and bulky versions with a sawblade back like the one made popular in Rambo; you couldn’t even puncture the soft natural rubber wheel of a MiG with one of those.

Next to the bayonet was a blurry photo of my platoon deep in Iraq a few weeks after the ground war officially ended, about 15 of us with a handful of Kurds outside of their village just before Saddam’s forces extracted revenge for them helping the allied forces. The photo was taken from a disposable film camera and blown up to 8×10, so though I printed it in 1991 it looked like the low-quality photos of Big Daddy from the late 1970’s. I framed it in brown oak to match the medal case, and both seemed equally archaic in 2019; Carleton’s friends were probably right, and judging by my bookshelf I was an O.G.

Tucked into the display’s frame was a ratty business card that was once new and white, but was now tattered and grey, with stains from 3-way gun oil, six months of eating MRE’s in Iraq without spare water to wash hands, tar from roadways melted by bombs, and a few drops of blood from a cut under my right eye in the first ground battle of Desert Strom, which confused me back then because I kept the card as a bookmark in a pocket-sized New Testament in my baggy right cargo pocket. The card showed a black skull wearing a black beret as the face of black Ace of Spades, and it was framed with Airborne wings (Airborne loves to put wings on everything). Simple but classic Times New Roman font said:

“I’m an American Paratrooper. If you’re recovering my body, kiss my cold, dead ass.”

I kept it tucked in a passage of Matthew that summarized what Jesus said about the commandments, not listing all ten but focusing on the big six, including not killing, and would sometimes wonder how Big Daddy could blatantly and repeatedly violate all of them without causing people to question his testimony against Hoffa or motives in the bigger picture.

Ken liked that card so much he adopted the phrase to describe what Chinese investors could do with their $10.7 Million. Carleton thought it was harsh, a common sentiment of his era, until I told him that it was banned before the ground war and commanders were ordered to collect them and all playing cards because of old Vietnam-era jokes of putting Ace of Spades on killed enemies, and some leaders actually did want us to have kinder gentler machine gun hands so they tried to stop us from honoring death. One of my platoon’s sergeants, a eurodite with a literature degree that didn’t have jobs in the mid 80’s so he joined the army, quoted John Donne at the beginning of Hemmingway’s “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” which was something like:

“Every man’s death diminishes me, for I am a part of man kind; therefore, do not ask for whom the bell tolls, it tolls for thee.”

My gaze settled on the faces in the photo. Almost half of us were gone. Several perished in Afghanistan, a few were disease (Gulf War syndrome), some were accidents (paratroopers tend to have risky hobbies outside of work), and a couple were suicides (vets have four times the rate as civilians). My gaze lingered too long, and I felt my jaw tighten and my lip quiver. I shook my head and took a breath and exhaled slowly.

Hope wasn’t deep asleep yet. I got into sync with Hope again, then returned to looking at the bookshelf.

The shelf below my row of nostalgia was full of dusty fiction and nonfiction I planned to read one day. The third shelf was mostly related to work. It had a collection of text books on engineering and physics, anatomy and physiology, differential equations and mathematical modeling; and a few pop culture physics books by Stephen Hawking, Carlo Rovelli, and Neil DeGrasse Tyson. There were signed copies of Panjabi and White’s classic Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine, and Vijay Goel’s Spine Biomechanics; Vijay earned his PhD under Panjabi and was tenured faculty at Iowa when I knew him, but Panjabi was the O.G. of spine biomechanics and pioneered using motion-tracking software to study cadaver spines. I still dabbled in consulting a few spine companies, especially because the new trend was computer-guided surgical systems and the new interest in machine learning.

The top shelf of the left hand bookshelf was dedicated to all five books in what fans reverently quipped as the Hitchiker’s Guide to The Galaxy trilogy, my cherished first edition of “A Confederacy of Dunces” from the LSU press, and an unfinished copy of Faulkner’s “As I Lay Dying” that I tried to get into once a year or so, but from the perspective of an omniscient reader I lost interest in the multiple perspectives of a dozen characters with narrow visions; it was like reading the plethora of books that each claimed to know what happened to Hoffa or Kennedy.

There were a handful of Lonely Planet and Let’s Go travel guides and a few trinkets picked up from a lifetime of sabbaticals, including a hand-sized vajra, the symmetric weapon of knowledge: one side represented the external universe we experience, the other side the internal interpretation we create, and where they met at the center was perfectly balanced.

The next two shelves were dedicated to well used copies of sometimes redundant and sometimes conflicting translations of ancient texts like the Bhagavita, Upanishids, Pali Canon, Bible (old and new testaments), Q’ran, Tao Te Ching, etc. There were a few copies of Native American stories of different tribes, and a few worn copies of Greek Myth collections with conflicting morals of their legends; that’s were Hope’s namesake originated.

In one version of Greek mythology, hope remained in Pandoras box – or jar, depending on the translation – as a gift from the god’s to help us persevere after Pandora inadvertently unleashed the god’s plagues upon mankind. In the other, Hope was personified as the most evil of goddesses, the ultimate cruelty from the gods, because Hope is what keeps a boxer who will inevitably loose in a ring, being beaten again and again for their amusement of the gods, as if they knew a wiser creature would quit. I told Dana that story when she visited me during my final days at LSU, and it made such an impression that fifteen years later she named her daughter Hope, and I felt a bit of connection to their family in part because of that.

The next two shelves had a curated collections of magic books, including several original and signed copies from Tommy Wonder, Chris Kenner, Troy Hooser, Brother John Hamman, John Rocherbaumer, David Roth, and a few others who made their way in and out of Baton Rouge and New Orleans on their lecture circuits in the 1980’s; a few from my era were signed to me, and a few classics like the Stars of Magic were signed by Dia Vernon and Larry Jennings but addressed to Doc Rogers, the Flim Flam Man, an older friend of mine from the magic club whose persona was similar to the psuedo confidence men, like the more well known magicians Doc Eason and Pop Hayden. His library was the size of my condo, and though he wanted to see his collection go to good use I could only accept a few curated books.

There was a Harry Anderson book, too, but it was less magic and more bar bets and friendly con games; that’s where I first learned the birthday paradox, before anyone could look up the secret on a smart phone. I sighed… Harry had passed away the year before from some type of lung clot following the flu, still a young man in his 60’s but with a body weakened from years of smoking and drinking. A street corner in New Orleans outside of his old bar was being renamed Harry’s Corner in his honor. Coincidentally, his widow had graduated from an all girls Catholic high school down the street from my school, Belaire, only a year after I graduated, which is part of what brought Harry down south and how I was lucky enough to see him perform for a few patrons who had no idea how famous he had been when I was a kid watching him laugh on Night Court once a week and entertain all of America hosting Saturday Night Live once a year or so for a decade.

I sighed again… I was feeling older than usual that night.

The next shelf was bulging with worn and marked up books about Jimmy Hoffa, the Mafia, and the Kennedy’s, curated from used bookshops over the years and more than 2,000 available on Amazon. Most were crap. I keep a bunch on my e-reader because I can search for names; there are probably 10,000 names to keep track of in all of that history. I wrote a few programs to analyze it using an archaic version of AI, but all it did was rephrase what other people said. I planned to print everything out one day, maybe using the media lab in the library, and sit down with a pen in hand and bottomless cups of coffee and unleash some old-school detective work, but I had been saying that for 30 years; I knew that planning to do it wasn’t getting me anywhere.

My gaze slid from the bookshelf and fell back on Hope. Her breathing was soft and regular. A siren sounded again, but her breathing remained unchanged. I turned off the light, crept into the hallway, and gently shut her door and pressed my ear against the thin wood panels.

The living room din was loud and mumbled into white noise. I heard John and Erin’s laugher above everyone else’s on the balcony. I held my breath and leaned into the door, but I couldn’t hear Hope’s breathing. I stood there a few more moments, breathing softly and appreciating the freedom to do it. A faint lion’s roar rippled across Balboa, through the forest of withering Redwoods, and into our building; it was inaudible in the hallway room, but I could hear it reverberating in the hollow wooden door just like the airplane engines. In the jungle, like in our city, the long wavelengths of a lion’s deep roar or a jets low rumble travel across plains and through forests or bricks. In the jungle, the range of their roar marks their territory. Though the Balboa Park Zoo was one of the world’s largest and nicest, animals were still caged, and I wondered if the lion knew that.

I realized I was slouching. I stood upright and pulled my shoulders back and took another deep breath. I exhaled slowly, and glanced at the illuminated hands on my almost archaic scuba watch, older than my new young neighbors from Metairie. I could see the hands without my glasses, and it was around 11:30, plus or minus a bit of blur. I walked back outside and joined my friends on the balcony.

The last of guests left around 1am. It was a good party, and I’m glad I hosted it. Mr. Charles was motionless in his sleeping bag and Miss Mary was fretting with hers, but she moved more slowly and less jittery than before, as if battling her demons had done her in for the night. I didn’t see the transients. They were probably behind the building and out of sight from the cars that drove along 6th avenue late at night. I stretched and sighed, and gently collected my things for a Lyft ride to the airport without waking anyone up.

I sat back on the balcony and kicked up my feet and rubbed my neck. The lion roared from its cage again, and an owl that lived in the Magnolia tree swooped silently past the balcony. I fished a Ballast Point Sculpin out of the cooler. I smirked: Ballast Point had just sold to an international alcohol conglomerate for $1.1 Billion, the same amount as Hoffa’s pension fund in the 1950’s, and that number was still unfathonable to me.

The Ballest Point founder, a UCSD graduate with a PhD in microbiology, had kept his original homebrew shop down the street from my perch in USD, and I sometimes swung by for a beer after leading courses in entrepreneurship in USD’s new innovation lab, named Donald’s Garage after Donald Shiley, the hands-on engineer who co-invented the world’s most successful heart valve in his home garage and in his spare time. His was made from pyrolytic carbon, the same material I used in my first venture, a wrist-resurfacing implant modeled after a San Diego fish-style surfboard, with a fin to keep the slick pyrolytic carbon implant stable in the radial bone; Donald’s venture was much more successful, and Pfizer bought it for around $800 Million back when that was an unfathomable buyout. His widow donated $21 Million to make a hands-on lab with Donald’s name on it. It’s full of the same maker’s equipment as the free downtown library. Students pay $56,000 a year to attend USD (more per year than I garnished with seven years of military service and a combat tour), and I point to the homebrew shop down the street and say entrepreneurship is more about following passions and luck in timing of markets, and I paraphrase Matt Damon in Good Will Hunting, that some people wake up a quarter of a million in debt with the same education they could have gotten with a dollar-fifty in late fees at the library. Donald earned $800 Million in his simple garage, and Ballast Point sold for $1.1 Billion doing what they would have done for free.