28 February 2019

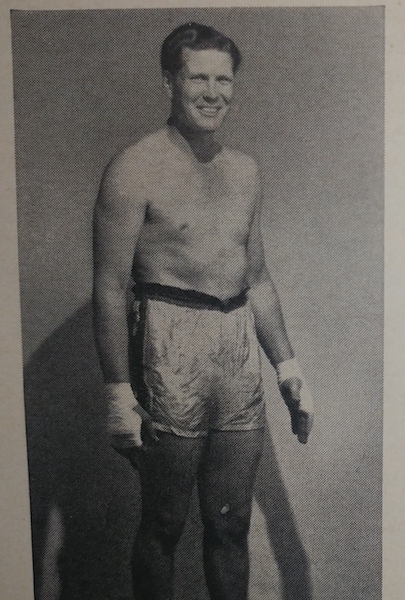

“Edward Grady Partin was a big, rugged guy who could charm a snake off a rock.”

Jimmy Hoffa, 19751

My buddy John finally reached the punchline: “Partin’s going to find out that his grandfather fucked Castro up the ass and called him Jimmy!”

Our laughter drowned the din coming from the dining room, and a couple of people doubled over so hard they spilled their beers. Five of us were on my balcony, overlooking Balboa Park to our east: 1,200 acres of rolling hills filled with dozens of gardens, museums, rolling bike trails, lush forests, and the San Diego Zoo. Less than a mile to our west, if we were in the condo of my neighbors and friends, Carleton and Linda, you’d see downtown skyscrapers, the airport, San Diego bay, and a glimpse of the navy’s underwater submarine base and the SEAL training area of Coronado Island. It was late, and my friends were drunk.

“Dude,” I said, “That was fucking hilarious!”

Levi pushed his glasses up and wiped a tear from his eye. He popped opened a can of Tecate and asked, “What’s your plan?” he asked, making “rabbit ears” for “plan” with the can in one hand.

I shrugged. Levi, who rarely asks direct questions, had asked a fair question given the party’s occasion: I was leaving on an early morning flight to Cuba, and would be gone at least a month. I didn’t have a plan, and I hadn’t read my Lonely Planet yet. Amazon delivered it a few days before, along with a copy of “I Heard You Paint Houses: Frank “The Irishman” Sheeran & Closing the Case on Jimmy Hoffa.” Martin Scorcese scored $257 Million to make Frank’s memoir into a film, and my grandfather, Edward Grady Partin, had a small part in it. I had nowhere to be for a month, and a brain full of names, descriptions, and stories; and an open mind to adapt to whatever happens, which the Tao Te Ching says is an ideal way to walk the path of enlightenment. Most friends can’t relate to that freedom, and they plan because they fear of not making the most of their measly two weeks a year of vacation. I was fortunate, and for almost thirty years I had taken an annual three month sabbatical without planning anything more than my departure flight. My friends knew this and rarely asked if I had a plan, but never before had I gone away hoping to learn something about my family. Levi’s question was relevant, and I had spent more time pondering what to do when I arrived in Cuba than I would discuss with my civilian friends, because I hadn’t told even my closest friends what I had been working on for years: an iterative improvement for democracy that aligned with modern technology.

Four of us were in a rare old building among the constantly evolving condos circling Balboa Park. Beside us, a historic building reportedly owned by a former president’s son but too expensive to preserve, was almost completely demolished to make way for yet another high-rise. Until that happened, my balcony had the best view in America’s Finest City. My feet were perched on wrought iron that made it look more like the balconies of New Orleans than the insipid west coast modern style, and that’s what had attracted me to the place a few years ago. A young couple originally from Metairie noticed it, too, and they recently moved into one of the west facing units. They made Cajun crab stuffed mushrooms for the dining table, and contributed two six packs Abita beers. I put one of the six packs to the hard sided cooler on the balcony, the one with with a bottle opener built into the handle that sometimes doubled as a seat when the balcony filled with more people than chairs, and the other was in a beer-and-wine fridge by the dining room table at the end of my condo farthest from the balcony, where a couple of dozen friends and neighbors were chitchatting and getting to know each other.

The owner of our building recently refused a $10.7 Million cash offer from Chinese investors who wanted to tear it down and build a multi-story building that would shade the sprawling southern Magnolia tree in front of us. If that happened, the 80 year old tree would fade away and die; it was already weakened from thirst in the dry southwest, and only maintained a few scraggly flowers rather than the skillet-sized and fragrant blooms back home. The building’s owner was Cranky Ken, an old-school guy who would be around my grandfather’s age, if he were still alive, and coincidentally the same age as the Magnolia tree, which had been imported along with tons of other trees from all over America as part of some garden exposition I can’t recall. Every spring, a family of owls nests in its thickly leaved branches, probably a welcome reprieve from the tall, thin palm trees that otherwise lined 6th Avenue; they were imported, too, but few people know that without water pumped in, almost nothing lives in San Diego, and that palm trees hide their thirst better than Magnolias.

Ken grew up working the docks of New York City. When he was probably 35 or so, around Carleton’s age, Ken already aging too much to meet the demands of a stevedore. He somehow scored enough money to move to the relatively nascent San Diego and buy a few buildings no one wanted, before it boomed and became America’s 7th largest city and every piece of real estate quadrupled in value; even the crash of 2009 was a negligible dip compared to what people paid in the 1970’s, bringing a 1000% return on investment down to a still respectable 975%. Our vintage red brick building was a bargain back then, and a few others Ken bough in what were then rough neighborhoods of San Diego (though nothing compared to his neighborhood NYC in the 50’s, he told me) were practically steals. Ken loved our building and the southern Magnolia tree in front of it.

“Those chinks would have to pry this place from my cold, dead fingers,” he told me early one morning, when he stopped by my balcony to collect quarters from our building’s laundermat. His accent was like you’d expect from an old dock worker from New York, nasally and harsh, and full of colorful words.

“This place will look like Central Park one day,” he cranked out another morning, waving his log of an arm towards the park’s lush forests, a rarity in Southern California’s arid desert. Had it not been for decades of irrigation and care, Balboa Park would like more like the rolling rocky hills of Afghanistan than Central Park; recent water restrictions were choking the Magnolia we both loved.

“People here don’t know how fucking lucky they are to have a tree like that. Look at those kids climbing it,” he said with a dismissive gesture of his sausage fingers. “Chinks, spics, negros, and wops, fags and queers: they all climb that tree now. A lot of Mexicans bring their kids here, too. It’s fucking beautiful. They don’t know how lucky they got it.”

His eyesight wasn’t good as it used to be, and I didn’t feel like telling Ken the hispanics and Asians were probably nannies of the mostly caucasian kids who climbed the tree; Banker’s Hill was named Banker’s hill for a reason. And the dark complected kids weren’t the immigrants of Ken’s immagination, people just off the boat who shared stevedoring work with people who grew up in old-school New York, like Ken had. Many were Indian software engineers, brought over by Qualcomm on work visas that made them wealthy by India’s standards but at around half the salary of local engineers from the UCSD Jacob Irvin School of Engineering, ironically created by the founder of Qualcomm (almost every cell phone in the world used a Qualcomm chip). We did have immigrants and refugees of Ken’s imagination a few miles away in City Heights, where the median income for a family of four was only $24,000, less than the monthly interest rates on my neighbor’s high-rise condo. Ken owned another building there, too, filled mostly with multiple Section 8 families cramming into single bedrooms against Section 8 codes, though Ken didn’t care much about codes as long as they paid their rent on time and didn’t call him to complain about anything.

I was unsure how Ken differentiated between spics and Mexicans, but San Diego’s population was around 42% hispanic and overwhelmingly from Mexico, especially with the border only a flat 16 mile bike ride away, or a quick trip from downtown via the Red Line. Downtown was down the hill from our building, a steep hill lined with more and more high-rises every year. As for queers, at the other end of Banker’s Hill was Hillcrest, America’s second largest gay and transgender community and home of the world’s largest rainbow flag, perched above a brewery with beers named “Thick and Stout,” “Pearl Necklace Pale Ale,” and a Sunday brunch with bottomless mimosas that took on a whole new meaning when bartenders wore ass-less leather chaps. But I knew what Ken meant. He was a product of his generation; in his first autobiography, Hoffa told America that my grandfather raped a Negro girl, and in Hoffa’s trial, even Chief Justice Earl Warren called the man my grandfather was supposed to bribe on behalf of Hoffa a Negro man. Adjectives meant a lot to Ken’s generation, which many people his age dubbed the greatest generation. For fun, just to watch him explode, I sometimes reminded Cranky Ken that Hoover was a closet homesexual, transexual, pillow-biter, or whatever word would ignite Ken’s fuse.

Cranky Ken was the type of person most people didn’t want to start a long conversation with, and you definitely never corrected his view of the world, unless you wanted to hear what a 15,000 pound bomb sounds like. His pitbull eyes were focused and beady, and he had a permanent frown framed by disproportionately large jowls. Coincidentally, he looked like Chuckie O’Brien, Hoffa’s adopted son (of sorts). In 2019, Ken and Chuckie were the same age and products of similar upbringings. Like Chuckie, Ken had muscles under layers his age that hinted to growing up boxing in rough neighborhoods. I never met Chuckie, but if he was anything like Ken, I think I’d trust him. And if I were in a tough situation and had to choose, I’d choose Ken or Chuckie to be in my corner over any one of the twats on SEAL Team 6.

Chuckie proved his tenacity in Hoffa’s 1964 jury tampering trial in Nashville, the one where Big Daddy was the surprise witness who sent Hoffa to prison. At the trial, Chuckie was sitting near Big Daddy when a gunman walked in the courtroom and pointed a pistol at Hoffa. Before courtroom security officers, Hoffa’s bodyguards, or the federal marshals hidden in the rows of seats could react, Chuckie leaped across his bench and tackled the gunman. He landed a fury of punches, ripped the gun from the larger man’s hand, and pistol-whipped him with his own gun. It happened so quickly that the would-be assassin was bloody and senseless by the time security guards could pry Chuckie off of him. (It turned out that the pistol was a pellet gun, but no one knew that at the time). After seeing the government-trained twats fail to do their jobs, or even the big brutes in Hoffa’s inner circle like my grandfather, Chuckie began patrolling the hallways with a .410 shotgun, staying awake and focused on protecting his idol and father-figure.

I can only imagine what Chuckie thought when, without his gun, Big Daddy stood up and sent Hoffa to prison; but I have an idea, because almost 60 years later Chuckie was still telling people: “Fucking Partin. I should have killed him when I had the chance.” To put that into perspective, Chuckie stood below Big Daddy’s nipples, yet he was unintimidated by a man who terrified everyone else in Hoffa’s circle.

Chuckie would have done anything for Hoffa. Sure, SEAL Team 6 can take out Osama Bin Laden in a midnight raid, but they had the support of President Obama and a few hundred thousand soldiers and spies. Chuckie had only a .410 shotgun, a bird gun the same shot strength as the 28 gage that years later Vice-President Dick Cheney shot his 78-year-old friend in the face with while they were duck hunting, doing no more harm than making Dick the Duck Hunter an internet meme for a while. And Chuckie didn’t have any type of weapon when he hurled himself past Big Daddy and between himself and his boss to tackle an armed man twice his size. Instead of a team of SEALs, I’d gladly ask Chuckie or Ken to be the pitbull in my corner.

I was lost in thought, no longer worried about a question I would rather avoid. John exhaled smoke from his Marlboro and pointed to my shoes dangling over the railing and said, “Dude, you have huge feet.”

I looked at him and held up my big hands and said, “You know what they say about people with big hands and big feet…”

I waited until a couple of the guys smiled, then I softened my voice and said, “It’s hard to find gloves and shoes that fit.”

Our laughter dimmed the dining rom din for a few brief moments, but was silenced by a siren sounding and blue and red lights dancing across the maroon brick balcony. An ambulance rushed past us on the way up from the way downtown, illuminating the otherwise dark view across Balboa Park. The doppler effect warbled as it passed us, and the the ambulance disappeared up 6th Avenue, probably on its way up the road to Scripps Memorial Hospital. In the relative silence and darkness from loosing our night vision, someone popped open the cooler. Ice rumbled and they fished out a round of fresh Tecates and Abita Ambers. I reluctantly declined. Carleton crunched his empty Tecate can under the sole of his loafers (they had a metal bottle opener under them) and accepted an Abita.

“I don’t have much of a plan,” I said to Levi. “I’m mostly going there to scuba dive and rock climb; I’m meeting a few guys I met in the Himalayas last year. But I’m meeting a friend in the state department to catch up and talk about Guantanamo, so I’ll probably listen to what he has to say about the Bay of Pigs fiasco, and then go from there.”

Erin, a lady more comfortable with Tecates and Marlboros than the wine and California charcuterie laid out on the dining room table, exhaled and said, “Of course you have a friend in the state department.”

I shrugged and said, “A lot of my buddies stayed in the service. The natural evolution was some type of special ops and then secret service. I don’t really know what he does, but he hobnobs with presidents and religious leaders, and shit like that.”

John lit another cigarette from the butt of his last one. I don’t know how he does it. He’s a big guy, around 6’2″ and 240 pounds, and he works almost 70 hours a week as a civil engineer with a desk job, but he can out-cycle me when we ride 16 miles to the Tijuana border and back for beer and tacos, and out-paddle me in any type of surf. He and his wife are empty-nesters, and her loud laughter from the dining room would pierce our balcony now and then; she hated when he smoked, which happened after a his first six-pack of Tecate was crushed for recycling and he broke out a backup 12-pack that he kept stashed in the wheelbed of his truck. We had a lot of time to surf and sip Tecates because their kids spent every other week with their dad. John adopted his wife’s kids, but viewed them as his and supported them keeping a relationship with their biologic father; when the kids went off to college, our friendship didn’t have to evolve, and the kids even joined us on the balcony now and then, asking questions like, “Who was Jimmy Hoffa?” Sometimes I wonder if John sets up his kids to ask that, just to poke me in the ribs without anyone knowing he’s doing the poking.

“After 9/11,” I said, “they bounced around all the new three-letter organizations. We’re all still friends and meet up whenever we can. I haven’t seen this guy in a few years, but we’re still tight.”

I nodded my head and glanced around and said, “It’s like hanging out with y’all.”

Levi and Carleton raised their cans as a toast. I raised an imaginary glass and caught eye contact; they rotated their heads and locked eyes with Erin and John before everyone sipped.

I looked at Erin and said, “You’d like him. He reads a lot, and he’s into kinky shit.” She smiled whimsically and raised a beer; we caught eye contact and she sipped without breaking it.

John snickered and said, “Erin wants to know his shoe size.” She didn’t deny it.

I told Levi, “My visa makes me use local businesses, nothing owned by the state, so I’ll probably just start up conversations and see what happens. And I’m meeting a few guys there to go a climbing in a small town a couple of hours from Havana. They’re on a journalism visa for what they call eco or adventure travel, but they want to get some politics through the Cuban editors about healthcare.”

Blank stares. John’s eyes were closed, and he giggled as he dragged on his cigarette. I paused to see if he’d share the joke, but he seemed happy in his own world.

“We’ll climb in a tobacco growing region with old-school guys,” I said. “Vin-yal-es or something like that.” (Despite living in San Diego for a long time and in Central America for a year and a half, my Spanish is muy malo. I hoped to improve it by having my phone off and getting away from tourist zones for a few weeks.)

“Huge limestone cliffs a couple of hours from Havana,” I added. “Fidel gave up smoking, but kept the cigar in his mouth for the image. He visited the farms for fun and photo ops. Rock climbing’s as an unnecessary risk for a national health system, so it’s illegal. That’s why the tobacco valley is still old-school. Maybe someone there will remember seeing my grandfather: he was remarkable looking.”

John’s guffawed and said, “Partin’s going to find all of the 70 year old Cubans with blue eyes who look like him, and go from there.”

John’s one of a few people know Big Daddy had sky blue eyes and strawberry blonde hair. Most photos of my grandfather in his prime are in black and white, and by the time people were used to color photos he had gray hair, and the poor quality of developing back then blurred his blue eyes to seem a dull grey-blue. But, in his prime, Big Daddy was one of the most classically handsome people you’d ever see: a smiling man who was tall, blonde, blue eyed, broad shouldered, and who had a narrow waist, a classic aryan look that Hitler and other white supremacists adored. After a late night of drinking, I told John about all of the blue-eyed people in Baton Rouge, Woodville, and Flagstaff who probably didn’t know they were my cousins, and that I avoided dating blue eyed girls when I was at LSU; he said that’s probably what led J. Edgar Hoover swooning over Big Daddy’s epitomization of the ideal man.

“Hey Levi,” John said. “If you’re Fidel Castro, what’s your safe word?”

“You mean Raul now.” Levi said.

John said, “Yeah, whatever. What’s the safe word for a Cuban dictator?”

“Free market,” Carleton suggested.

“Hurricane,” Erin said.

“Rough Rider” I said. John countered: “Dude, that would just make him hornier.”

“Harder?” Levi joked, a play on our last meetup where John asked, “What are the top 10 worse safe words?”

We laughed for a minute, and then the conversation stalled.

“What about Hoover’s safe word?” I asked.

“Easy,” Erin said. She waved across Levi’s puffy hair. “‘Communist’ would make him softer than Levi’s hair.”

John guffawed and said, “Saying ‘Big Daddy’ would make him harder than Chinese algebra.”

When the laughter died down, I said, “I was thinking of using the climbing trip to write a memoir, sort of like Wild.”

“I loved that movie!” Erin said in her high-pitched voice. She calmed down and said, “And the book. I always wanted to hike the Appalachian Trail. You should do that.”

I shrugged. I’m sure she meant the Pacific Crest Trail, which passed in the deserts and mountains near San Diego, and not the Appalachian Trail along our east coast. In Wild, the author was one of the early hikers of the Pacific Coast trail, and she explored backstory under the umbrella of her three-month hike along the west coast.

She exhaled smoke and said, “Why don’t you do it? You’re The Most Interesting Man in The World.” That’s the nickname working friends give you when you disappear for three months a year.

Erin spent her ample vacation time traveling the world with focused itineraries so that everyone on her Facebook feed would know she had an adventure. When home, she hosted a huge block party after every year’s Pride parade, the one that passed my balcony and followed the equally sized but much more tame St. Paddy parade, and she dreamed of retiring from her architecture firm and setting up her own shop on some Carribbean island – any one, just as long as they still had beer. I don’t think she had a safe word. Despite her diet, Erin was an avid hiker, and she lived in Hillcrest so she could huff and puff Balboa’s five miles of single-track trails during lunch breaks. She hoped to meet a man who wanted to settle down. I joked that she was in the wrong neighborhood and attended the wrong parties. Her Pride party brought in a hundred gay guys in better shape than any of us – a commedian in the 1990’s said he didn’t want to be gay, but he wanted to be in gay shape, because apparently it took a lot of muscle to suck dick. At my parties, most of my friends were happily married. In Hillcrest, the biggest compliment she’d get was from cross dressing men who liked her shoes, and who also had no safe word.

She dropped her cigarette into a Sierra Nevada bottle half full of luke-warm beer and cigarette butts. It sizzled and extinguished. The smell waifed out and made me slightly nauseous – it’s funny how you notice those things when you’re not drinking heavily but your friends still are. John put his out and lit another. Erin’s a finger width shorter than John, a bit heavier than average, and can out-swim me. I don’t get it.

Erin fished another beer from the cooler and asked me, “Who was that guy playing your grandfather in the new Scorcese movie? The one who called you when they were filming?”

“Craig Vincent,” I said.

Blank stares.

“Remember Casino?” I asked.

Most people nodded or grunted yes. Carleton said: “Casio was a 1995 Martin Scorcese about Las Vegas, starring Al Pacino and Joe Pesci.” There were a couple of “oh, yeah”‘s.

Carleton was a film buff. He and his wife were DINKS, Dual Income No Kids, and about 15 years younger than the average age of our group on the balcony. Like a lot of young people in my neighborhood, they paid to live there and lived a modest lifestyle in exchange. They spent a lot of time in the downtown public library scouring old films, and browsing local vinyl stores and other things deemed “hipster” by kids their age. When I tag along, record store workers called me “O.G.,” Original Gangster. As evidence, they point to my hipster hat – coincidentally a Cuban styled bolero – and an unplanned hodgepodge of tattoos that make up my arm sleeves.

Sometimes, to spite the vinyl-coveting hipsters, I’ll mention I have a worn original copy of Fleetwood Mac’s Rumors from 1979, or Tom Wait’s Heart of Saturday Night, from when he lived in San Diego in the early 70’s. If I really feel like tormenting them, I’d say I’ve seen both live: that gets the attention of every collector in the store. Nothing beats an eye witness. Even

A few times over the years Carleton and I stayed up late, passing glass bowls of high end weed back and forth, and in the predawn hours when Cranky Ken walked by to get quarters he’d stop outside the balcony and chat us about old gangster movies. He likes us, because we appreciate his balcony. Carleton and I joke that my rent is a song and occasional story, but there’s probably truth to that. Ken was remarkably timid when asking me what I remembered, and when I share a story it’s the only time he refrains from offering his opinion, other than to say the Brian Dennehy did a good job portraying him in 1983’s Blood Feud. Enough people remembered Big Daddy that I didn’t have a plan other than to meet people who would have been Carleton’s age in the 1960’s, around my grandfather’s age back then, chat with them, and go from there. Big Daddy makes a lasting impact, and it’s likely that someone in Cuba would remember seeing him.

I said: “Craig was the big dude in a cowboy hat that Joe Pesci reached up and slapped because Pacino told him to.”

John chipped in, “Did he slap him and say, ‘who’s your big daddy now!'”

When I stopped laughing enough, I wiped both eyes and said, “I have a theory.” My smile returned to its resting state, and I said, “About The Godfather. I started thinking about it after Craig and I talked.”

“I reread a book by some mafia guy,” I said. “At one of the used book shops in North Park. I can’t recall his name – but he was the confidential advisor to Scorcese on The Godfather.”

“That was Francis Ford Coppula,” Carleton interjected. “Not even on the same scale.”

“Thanks,” I said. “Coppula. Anyway, the guy wrote something that stuck in my mind.”My hand made a gesture as if holding something briefly, then tossing it over the balcony, and I said, “It was off-hand, as if even he didn’t get it. He was an intermediary between Coppula and the mafia. They wanted to be anonymous, but they wanted the film to show them as families more than gangsters.”

My face froze for a moment. For the first time, I heard myself say it out loud: “I think the horse head scene was a loud warning shouted to Hoffa from inside the biggest movie of our generation.”

I glanced around and saw blank stares on every face except Carleton’s. He misunderstood the blank stares, and said, “There was a scene where a Hollywood film producer woke up with his race horse’s bloody head on his bed.”

Everyone knew that, but Carleton’s comment set up what I wanted to say. I said, “Hoffa used to fund Hollywood films with the Teamsters Pension fund.”

I paused for effect and then said, “It was around a billion dollars back then.” The 1994 expose book on the Teamsters, called The Teamsters, estimated the pension fund at $1.1 Billion in untraceable cash controlled and dolled out by Hoffa. In today’s money, it was as if Hoffa were on par with Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and other Billionaires who run the world.

“He also lent it to the families to build Vegas casinos and New Orleans hotels.” I said. “But Coppula would have known about Hollywood and seen The Teamsters logo across the final screen of credits. The logo was two horses, Thunder and Lightening, from when the Teamsters drove horse waggons. They’re behind a huge, blue, ship’s steering wheel,” – my head cocked and I paused a brief moment – “or dharma wheel. It’s impossible to miss,” I nodded towards Carleton, “if you sit through all the film credits.”

“Hoffa was in jail then,” I said too rapidly, “and negotiating with Nixon for a pardon. I think the families were telling Hoffa that his power was through with them and Hollywood, and they were warning him to keep his mouth shut around Nixon. B’…” John’s face began to crinkle with expectation. “…My grandfather wasn’t changing his testimony, and Life magazine went full-coverage that, saying Marcello trying to bribe him on behalf of Hoffa.”

“Pundits dismissed it,” I said. “They said the mob didn’t bribe. But they probably didn’t read the details of why Hoffa was in jail before flapping their lips. It’s no different than today. When the mafia failed to change my grandfather’s mind, I think the families were worried Hoffa would talk when he got out, so they had Coppula add the horse head scene to send him a message.”

For the first time that evening – and in general – John had nothing to say. Levi was looking up thoughtfully, and when he smiled I knew he connected the dots and saw a bigger picture. Even Carleton looked like he had learned something. Erin’s gaze was on me, and she was smiling as she sipped her Tecate. Levi smirked and fished around the cooler for a bottle of Sierra Nevada. Everyone refilled or relit, and my mind wandered.

Beyond Levi’s shoulder, under the dim yellow light of a square, Spanish tiled public restroom across the street, I saw Mr. Charles bedding down for the night beside the men’s door. The year before, after sharing some red beans and rice and a generic hybrid joint, I taught Mr. Charles how to pick the 1950’s-era lock and gave him one of my older pick kits. That year, downtown San Diego had an outbreak of Hepititus that slowed tourism and made national news, because it was attributed to the roughly 6,500 homeless people around downtown and Balboa Park, and every year some media outlet focuses on the homeless in San Diego and LA around elections. Giving Mr. Charles access to a bathroom after the mayor locked it was the least I could do for him and my neighbors. A few of my friends knew I fed homeless people in Balboa, but none knew I taught them how to break into bathrooms. Erin said that I was a “nice guy,” but if that were true, Mr. Charles would be on the balcony sipping beer with us, or in the dining room, nibbling on some California charcuterie, commenting on its vegetarian, vegan, and gluten free options, and chatting with everyone about what they did for work. Instead, I was watching him bed down beside a public bathroom.

After some parties, the rare ones were I wasn’t drinking, I dodged cars on 6th Avenue and brought him leftovers and a joint every now and then. To not make it like charity, I told him the bag of weed was a gift from Uncle Sam; local dispensaries offered a discount for disabled veterans, and the VA recently assigned me a 70% rating. I received half off campsites in national parks, $1,317 a month to blow in a city where rent on a one-bedroom hovered around $2,000, and 25% off weed. Mr. Charles had briefly served in the reserves some time in the 1970’s, but had no disability to fall back on and was okay with that. I was lucky, he said. His body probably hurt as badly as mine from his decades of labor, yet he never complained. He was bidding another two years until he was eligible to start collecting Social Security, and he viewed Balboa Park as a free campground. I told him he was better off than I was, because I still had to pay half price when I went camping, and he got free weed delivered to him; that made him laugh, and Carleton kept telling me that was better than what anyone else would give.

On the other side of the building from Mr. Charles, Mary was bedding down beside the lady’s room, barking something to people who weren’t there. I don’t know her story, but for almost two years she had never complained about life to me, which is more than I could say for most of my friends. Behind the building, facing away from 6th avenue and towards the irrigated forests of Balboa Park, two jittery transients I didn’t recognize were collecting newspapers and cardboard for a bed. I couldn’t hear what Mary was mumbling over the laughter bubbling from my living room, but she seemed upset at whatever she saw in her mind’s eye. Like with Ken, I avoided long conversations with Mary. The transients attracted my attention, if only because I was worried about her safety.

Levi broke my train of thoughts by asking: “Hey J, can I see your knife?”

I leaned to my left and slid the orange rescue Leatheran tool clipped inside the right pocket of my blue jeans, and handed it over with the carabinner and bottle opener side facing Levi. He took it and popped his cap and tossed the Leatherman back to me. I returned it and adjusted a thumb tip with a small red handkerchief that I had put in my pocket earlier that day (one of the simple flesh-colored ones available at all magic shops that can hide a small handkerchief inside). The patents for Tim Leatherman’s now-ubiquitous multi-tool expired probably ten years before, and like most outdoor-products with a lot of competition, multitools kept pace by adding a bottle opener; it was the most used tool on my current multi-tools. Levi liked using it; it has a nice feel in his hand, which is much smaller than mine. I thought about chiding him for not using his lighter or an obvious opener, then I remembered that I never mess with Levi.

If it weren’t for Levi, I’d be the runt of our litter on the balcony. He’s a 5’4″ thin jewish guy from Santa Monica who can eat whatever he wants without gaining girth. With curly hair, thick designer glasses and an erudite demeanor, he looks like Malcom Gladwell, or like Seth Godin wearing a floppy afro wig. His personality matches Malcom and Seth: he’s the type of guy who carries a thesauruses into a dive bar. Aran graduated from UCSD in software engineering, and has been in San Diego since.

Earlier that evening, Aran’s wife, a San Diego native and the primary reason he lingered here, lost their coin toss and took their two boys home in time for bed. It wasn’t a surprise, and happened every time I hosted a party. He has two double-sided quarters, and alternates using the heads and tails, though most people know it and never make bets with him. His oldest kid is a taller version of Levi with a Hebrew name I can’t pronounce, and is a budding magician. Levi hopes he’ll figure out the double sided coin on his own, which he thinks is a stronger lesson than being told.

Levi is patient. He once hacked the bluetooth stereo in a friend’s new Audie, and and made it play the theme song to “Taxi” when stuck in traffic by linking it to Google Maps’s traffic feature. The Audie technicians couldn’t reproduce the error or find anything wrong in their computer diagnosis, and that went on for five years, until the friend upgraded to a car with Apple play. Levi is still working on hacking Apple.

And when we planned a magic trick for his office, Levi spent two years discretely asking for dollar bills in exchange for four quarters, ostensibly to use the dollar-only vending machine, but secretly planting quarters with pre-planned patterns of dates and states. When I arrived for a workshop on probability and statistics in machine learning, I demonstrated some of the points Levi had already made about predictive programming by getting his team of around 40 people to share their birthdates: two pairs were shocked to have the same birthdate. I gave a break where they could use their phones, and a few found out about the birthday paradox. I admitted that’s what it was, and said I was glad they could find it. Later, when I showed how subconscious biases influence our choices more than probability or statistics, proven by the remarkable difference between the states shown on quarters kept in females’s desks vs the quarters kept in males’s desks, no one could find an answer for how it was done. A year later, Levi says they’re more intentional in where they sit or stand at meetings, or with whom they go to lunch, so our deceit may have helped their team function more smoothly.

He thinks long-term and he has the patience and precision of a deep-cover agent, which why I never mess with Levi.

He handed the Leatherman back to me. I accepted it and said, “I still don’t get the point of a entrepreneurship visa.”

I spun the Leatherman around my palm and flipped it over a few times with a flick of my fingers to show both sides. I caught it with the bottle opener side facing away from me, and held it up.

“I think in terms of innovation. A lot of people think innovation is adding more gadgets, like a bottle opener, and that entrepreneurship is selling your gadget. I’d like to get people thinking about solving problems that aren’t obvious yet.”

“That’s what you do at USD, isn’t it?” Erin asked.

I shrugged. “Sort of. I’m more coaching teams that already have an idea and a prototype. But they grew up in a culture that treats education less like job training, and more like a training camp for the real world. It’s a mindset that’s easier to accept the younger it begins.”

I heard a little girl’s voice from inside say, “Uncle J?” I leaned forward and slid my feet off the balcony and onto the floor, and stepped through the double French doors into the living room where a tired looking eight year old girl stood. I took a few steps towards her, tucked my Leatherman into my right jeans pocket and held on to my pockets with both hands as I kneeled down to her eye level; the larger motions covered my right thumb stealing the thumb tip from the small pocket of my jeans. To further distance my right hand from action, I used my left hand to rotate my baseball cap backwards, a habit she’d be used to, because I do that to keep the brim from hitting her forehead when we speak softly and my face is near hers so I can hear.

I rested both hands on my left knee, smiled, and said: “What’s up, sweetie?”

I have a nice smile. I inherited it from Big Daddy, and it’s nothing more than an effect of our high round cheeks and the muscles that pull up on the corners of our mouths. I also inherited his shoulders, which makes sense if you ever saw a photo of us without our shirts on; our muscles ramp up from our shoulders to our ears and give the impression we’re stronger than we are if you’re looking at our torsos. But I have thin wrists and forearms, which, next to my big hands, makes me look weaker than I am; Big Daddy had the thick wrists and forearms, not as big as Popeye’s forearms, but big enough to give the impression that he was much stronger than he was. And it helped him escape handcuffs; apparently, he was able to escape from prison and police when younger without much training. I had spent years reading Houdini books on how to escape anything, and learning under The Amazing Randi, when he was on his crusade to expose pseudo faith healers that were abundant in the south back then, but when handcuffs were tightened around my thin wrists I could never get them over my wide hands. Instead, I learned to pick locks from improbable angles using my long fingers. But I never did well as an escape artist: the smile I inherited from Big Daddy has the problem of making everything I do seem effortless.

I still think of “we” when I talk about traits I inherited from Big Daddy. When we’re just sitting there, people think we know something they don’t. When we really smile, our cheeks crawl up to the bottoms of our eyes and take the corners of our smile with them. After testifying against Jimmy Hoffa and being threatened by mafia hitmen in the courtroom – they showed Big Daddy a flick of their finger against their teeth, a code for a price being put on your head – he answered a reporter for Life, who asked if he were scared, without answering directly; he said, “I just smiled.” The photo Life chose showed him smiling, and that told America all they needed to know.

Big Daddy used that smile on all the ladies in Baton Rouge, and around his daughters and us grandkids. I, too, crinch my eyes when really smiling, and anyone watching me smile at that moment would have thought I was in love. They’d be right, depending on how you define love.

“Momma said you could tuck me in,” Hope said.

I saw Dana watching us from the corner of my eye. She was holding held the same can of Abita Amber that she’d probably been nursing for an hour or two, and she had a smile that was softer and kinder than anything I could muster.

Dana didn’t have a resting smile and a genuine smile, she simply had a smile. She’s a finger width taller than I am, but doesn’t look it for some reason – most people are surprised at how tall she is when we stand together, as if her kindness makes her seem smaller for some reason; that’s probably why Big Daddy looked bigger than he was. She’s thin and athletic looking, though after the army her only exercise was hiking near her home in Topanga Canyon, mostly in Malibu State Park, and an occasional backpacking or easy rock climbing trip with me around Idylwild or Joshua Tree. She used to play beach volleyball, but stopped because it wasn’t as fun after she dropped out of college to pursue art full time.

She works in movie studios most days and doesn’t get a lot of sunshine, but she looks tanned because her biologic father was, coincidentally, a jazz musician from New Orleans and 1/2 Creole, meaning at some point at least one of his Spanish or French ancestors slept with a slave. Dana’s mother met him after he performed one night in 1971 at the then-new Baked Potato jazz club up the street from the Magic Castle, when Sanford and Son was still on television and Redd Fox was a regular and Dana’s mom was into jazz and standup comedy. He left the next morning and continued his tour, and he probably never learned that Dana was born ten months later. Except for four years in the army, she’s been near her mom and Hollywood ever since. People assume her complexion is from California’s sunshine tax, especially because Hope has a complexion as light as mine, but curly hair like Dana’s. When we’re together, people assume we’re a family.

I kept my gaze on Hope and said of course. I stood up and pulled my jeans up and tucked the thumb tip back: it wasn’t the right moment. I lowered an open, now-empty hand, and Hope put her’s in mine and made a loose fist. Her hands were the size you’d expect for an eight year old girl, and I’m not tall, only 5’11” in the mornings (most people shrink around 1-2 cm by the end of the day because our intervertebral slowly discs compress under load and rehydrate overnight), but I inherited Partin-sized hands and feet that need XXL gloves and 14W shoes. My loose fist swallowed her relatively tiny hand, which made her seem even more petite. I saw Dana beaming in my periphery, and my smile broadened. It really is a nice smile; Dana said it was the first thing she noticed about me when we met at Fort Bragg a long time ago.

Hope and I turned right into the doorway of my office and library. The futon couch was open and made for Dana, and a plush car-camping inflatable mattress was on the floor for Hope. She had put her weekend backpack beside her mattress when they arrived, nestling it near her shelf on the right side bookshelf.

The mattress nestled between two bookshelves that framed the new view of downtown, possible in the short time between when that old building was gone and the underground parking of a new high-rise was under construction. The bookshelves made the window look like a large television framed in an entertainment center. Through the window, I saw the lights of an airplane approaching for landing, and a moment later I heard the dull roar of breaking jet engines subtly rumbled through our walls. I stretched and moved my left arm into my periphery; it was around 11pm, so that should be the last plane of the night. After 11pm, the airport fined airlines $75,000 for landing, thanks to the people in Point Loma who bought during the 2000’s housing boom and woke up surprised that their multi-million dollar homes were in the flight path. Our condo, like most on Banker’s Hill, accepted a deal from the airport to replace all old windows with new noise-dampening ones, but the low rumble still made it through our wooden frame. I closed the black-out curtains and dimmed the lights, tucked Hope in, and sat cross-legged beside her mattress.

She tried to talk to me as she laid down, but she was too tired. She stopped talking and her eyes remained shut, and within two minutes her breathing was slower but still irregular. I’d wait until she was fully asleep before leaving.

I straightened my posture and rested my hands on my thighs, and focused on breathing softly to help her fall asleep. Someone glancing in would have thought I was meditating; it wouldn’t be far from the truth, depending on how you define meditate. Another airplane rumble rippled gently through the room. I slowly moved my head as if bringing on ear to my shoulder, then back to the other side. The muscles were tight, and I had to strain a bit but still didn’t approach the flexibility I had as recently as seven years ago. To steer my mind towards something else, I scanned my bookshelves.

The bottom two shelves of the right-hand bookshelf were for Hope and Dana. The bottom shelf had a short row of books Hope had outgrown one the years, mostly ones typical of her age and with a bias towards princesses and fairies, and a few drawing pads and colored pencils that were timeless. The shelf above had what I thought or hoped she’d enjoy while I was in Cuba, books like the Harry Potter series and some science fiction series about a kid a few years older than her who had multiple universe versions of himself to help solve crimes (I bought it on impulse when the cute worker at a used bookshop in North Park recommended them for an eight year old who read above her level). I added a couple of maker’s project books and a maker’s kit that I had designed for anyone from around age ten to a freshman in college engineering; it had typical nuts-and-bolts and wires-and-circuits, but I added a few Arduinos and things it could make move, beep, light up, or roll. I hoped Dana would help her with the online parts; she’s never been interested in computers, but maybe a shared project would prime her pump.

For Dana, I added a couple of the new Stephen King books that had already made their way to the used book shop. She’d have access to all of my home and books, but she liked popular fiction like Stephen King and a few other authors I can never recall; the lady at the bookshop recommended them based on Stephen King’s “The Stand” and his Gunslinger series, which he said all his books were leading up to.

The upper three shelves of that bookshelf were mine. The top shelf was mostly memorabilia, a small display of medals from the first Gulf war and my time as a peacekeeper in the Middle East (we didn’t succeed). A stand meant for photos displayed the Vietnam-era bayonet I used in the battle for Khamisiya, a relic when it was issued to me in 1990, but the only one available in the scavenged armories leading up to the first Gulf war. Next to the bayonet was a blurry photo of my platoon, taken from a disposable film camera and blown up to 8×10 and in a brown oak frame that matched the medal case.

My gaze settled on the faces in the photo. Almost half of the 21 of us were gone. Several perished in Afghanistan, a couple were suicides (vets have four times the rate as civilians), a few were disease (Gulf War syndrome), and some were accidents (paratroopers tend to have risky hobbies outside of work). Our network had lost contact with a two. One recently put the barrel of a Glock 19 in his mouth, standard issue for police, Rangers, and secret service back then, and he had been on my mind all month.

I shook my head and took a breath. Hope wasn’t deep asleep yet. My heartbeat was up. I got into sync with Hope again, and returned to the bookshelf, unafraid to look this time.

Tucked into the display’s frame was a ratty business card that was once white, but was now the color of Dana’s skin and stained with blood, 3-way gun oil, and six months of MRE lunches. It had a black skull wearing a black beret as the face of black Ace of Spades, and it was framed with Airborne wings. Times New Roman font said: “I’m an American Paratrooper. If you’re recovering my body, kiss my cold, dead ass.” Ken liked that card so much he adopted the phrase to describe what Chinese investors could do with their $10.7 Million.

The shelf below my row of nostalgia was full of dusty fiction and nonfiction I planned to read one day, a combination of books like Sapiens and Blink mixed with classical literature and memoirs by a few presidents and average, ordinary people like you and me who somehow made art from their history in work like Angela’s Ashes, The Liar’s Club, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, and The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien (no relation). Three new books from Amazon were squeezed in, Mary Karr’s “The Art of Memoir,” Sol Stein’s “Stein on Writing,” and Stephen King’s “On Writing.”

The third shelf was mostly related to work. It had a collection of text books on engineering and physics, anatomy and physiology, differential equations and mathematical modeling; and a few pop culture physics books by Stephen Hawking, Carlo Rovelli, and Neil DeGrasse Tyson. I had signed copies of Panjabi and White’s classic Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine, and Vijay Goel’s Spine Biomechanics; Vijay earned his PhD under Panjabi and was tenured faculty at Iowa, but Panjabi was O.G., and I like looking back at what we knew then versus what we know now. Most of the cadaver work had been improved by faster computers and more efficient algorithms (my 1997 master’s thesis contributed to that), and I dabbled in consulting a few spine companies. I center around how most people don’t know that President Kennedy had Harrington rods in his back from before he was a senator, and that was in the 1950’s. We still use them, though without Kennedy’s team of physical therapists and doctors following through for years.

Modern spine surgery has improved fusion rates of two vertebra together, but has not improved patient outcomes. Kennedy was lucky. He knew to avoid a spiral of negative thoughts by focusing on his work, his family, and Marilyn Monroe, and I’ve never forgotten that in my work designing spine implants and treatments. Despite advances in technology, prevention and follow through, combined with perspective, are still the best medicine; unless it’s cancer, then by all means get it cut out right away. Then go spend time with someone like Marilyn Monroe to keep your spirits up. No one knows who pays for all of that, so companies keep making better versions of Harrington Rods and fusion cages. In 1996, after the FDA changed fusion cages from Class III (hard to get) to Class II (easier), the market skyrocketed to around $4 Billion a year annual. It was so huge so fast that the inventor of fusion cages, a surgeon in Los Angeles, became the world’s first overnight billionaire when Medtronic paid him $1.1 Billion for his patents. That’s much, much more than I ever made as a magician or spine implant consultant; I don’t know why I still consulted for spine companies, but it’s probably just an excuse to see old friends and make jokes about Marilyn Monroe that no one else would get.

The top shelf of the left hand bookshelf was dedicated to all five books in what fans call the Hitchiker’s Guide to The Galaxy trilogy; though I’ve read all five books a few times, I had yet to find the question to Life, The Universe, and Everything. Beside those five books were a handful of Lonely Planet and Let’s Go travel guides and a few trinkets picked up from a lifetime of long sabbaticals, like an astra from the previous year’s trip to northern India, an illegal piece of the pyramid Cheops given to me by a friend who worked there, and a fist-sized chunk of the painted-side of the Berlin wall given to me by a friend of sorts when I trained former east German paratroopers on NATO weapons and communications systems. That evolved to me being pretty good at computer controlled spine surgery systems. I still keep in touch with old army buddies when I travel, because they can make jokes about the Berlin wall and different torture methods that no one else gets.

The next two shelves were dedicated to well used copies of sometimes redundant and sometimes conflicting translations of ancient texts like the Bhagavita, Upanishids, Pali Canon, Bible (old and new testaments), Q’ran, Tao Te Ching, etc. I had a few copies of Native American stories I hadn’t red yet, and worn copies of Greek Myth collections that contradicted each other and were Hope’s namesake.

In one version of Greek mythology, hope remained in Pandoras box – or jar, depending on the translation – as a gift from the god’s to help us persevere after Pandora inadvertently unleashed the god’s plagues upon mankind. In the other, Hope was personified as the most evil of goddesses, the ultimate cruelty from the gods, because Hope is what keeps a boxer who will inevitably loose in a ring, being beaten again and again for their amusement of the gods, as if they knew a wiser creature would throw in the towel and go have a beer with friends. Hope’s used in the bible countless times, and one of my first tattoos is a small tattoo of hope in simple black letters on my inner bicep, crude and irregular, almost like a prison tattoo, and it was from one of the first times I was drunk and more to make a point than any singular belief, other than a belief that words don’t mean much, especially when drunk.

When I was in the Middle East with an ambiguous title of “communications liaison,” I learned that most tension came from different definitions of the same words, like kill versus murder, sacrifice, and honor; I spent more time ensuring we all used the same definition than preaching one version or the other. I told Dana that story when she visited me during my final days at LSU, and it made such an impression that fifteen years later she named her daughter Hope, saying that with the knowledge of where her name came from, she would not be attached to one definition or another. Hope could be free to make her own choices, she said. Dana was smarter than I was, and she had no tattoos and hadn’t been drunk since her first year in the army.

The next two shelves had a curated collections of magic books, including several original and signed copies from Tommy Wonder, Chris Kenner, Troy Hooser, Brother John Hamman, John Rocherbaumer, David Roth, and a few others who made their way in and out of Baton Rouge and New Orleans on their lecture circuits in the 1980’s. There was a Harry Anderson book, too, but it was less magic and more bar bets and friendly con games; that’s where I first learned the birthday paradox. I sighed a bit. Harry had passed almost exactly a year before at age 65. After Night Court, he married a girl from Baton Rouge and moved to New Orleans to run bar, and, like a lot of people in Louisiana, he smoked and drank more than was healthy. My friends in the magic club missed him as if he were an old army buddy.

I moved my gaze away before I dwelled. The only newer magic books were the six volumes of Robert Giobi’s Card College and some reissued books on performance theory by Juan Tammariz, and two booklets with dozens of authors contributing and published by the owner of The Magic Apple, a magic shop located up the road from Hollywood’s Magic Castle. I had a few collectors books from a friend’s collection, like original signed Stars of Magic series from the 1950’s and 60’s, including a coveted Dia Vernon scribble to my buddy Steve, and a few obscure pamphlets by magicians known to only a few of us, like Birmingham’s Michael Baker, a soft spoken artist with layered meaning in every routine, and San Diego’s J.C. Wagner, a pink-nosed alcoholic who could brilliantly entertain an entire bar with his wit and a deck of cards.

Because my bookshelves were stuffed full like a Thanksgiving Turkey, I added a few cookbooks beside the magic books, including my grandmother’s roux-stained copy of Louisiana Kitchen: I quipped that turning raw ingredients into dinner was like magic, a play on Paul Prudhome’s “Louisiana Magic” seasoning products that were popular when I was growing up, and are, despite Paul passing away years ago, still on grocery store shelves across America without anyone knowing who he was; a plump, jolly, uneducated man who loved his job and was the only non-Frenchman to win France’s chef of the year award, and then cooked dinner for President Reagan and Prime Minister Gorbechov’s first peace summit in an effort to end the cold war. Though I make my own seasonings, I respect that Paul was the O.G. of Cajun cuisine.

The next shelf was bulging with worn and marked up books about Jimmy Hoffa, the Mafia, and the Kennedy’s, curated from used bookshops over the years and more than 2,000 available on Amazon. Most were crap. I keep a bunch on my e-reader because I can search for names; there are probably 10,000 names to keep track of in all of that history; Walter Sheridan’s index of names in “The Fall and Rise of Jimmy Hoffa” is longer than most people’s books on the subject.

My gaze slid from the bookshelf and fell back on Hope. Her breathing was soft and regular. A siren sounded again, but her breathing remained unchanged. I turned off the light, crept into the hallway, and gently shut her door and pressed my ear against the thin wood panels.

The living room din was loud and mumbled into white noise, and I heard John and Erin’s laugher above everyone else’s on the balcony. I held my breath, but couldn’t hear Hope. I stood there a few more moments, breathing softly so I could hear her silence. A faint lion’s roar rippled across Balboa, through the forest of withering Redwoods, and into our building; it was faint, but I could hear it reverberating in the hollow wooden door. In the jungle, the long wavelengths of a lion’s deep roar travel across plains and through forests and marks their territory. I wondered if the lion realized it was in a zoo.

I realized I was slouching. I stood upright and pulled my shoulders back and took another deep breath. I exhaled slowly, and glanced at the illuminated hands on my almost archaic scuba watch – it was older than my new neighbors from Metairie. I could see the hands without my glasses, and it was around 11:30, plus or minus a bit of blur. I walked back outside and joined my friends on the balcony.

The last of guests left around 1am. It was a good party, and I’m glad I hosted it. Mr. Charles was motionless in his sleeping bag, and Mary was fretting with hers, but slowly and silently as she and her demons drifted off to sleep. I didn’t see the transients, but they were probably behind the building and out of sight from the cars that drove along 6th avenue late at night. I stretched and sighed, and gently collected my things for a Lyft ride to the airport without waking anyone up.

I sat back on the balcony and kicked up my feet and rubbed my neck muscles. The lion roared from its cage again, and an owl that lived in the Magnolia tree swooped silently past the balcony. I popped open a beer with my knife, poured it in a glass, and relaxed.

Go to The Table of Contents

- Chief Justice Earl Warren concludes his three page missive about Big Daddy with these three sentences:

‘This is a federal criminal case, and this Court has supervisory jurisdiction over the proceedings of the federal courts. If it has any duty to perform in this regard, it is to see that the waters of justice are not polluted. Pollution having taken place here, the condition should be remedied at the earliest opportunity.‘”

When I shared that quote with John, he burst into laugher and blurted out: “I wonder what Warren would say about the turd still floating in the swimming pool of justice!” That turd is my grandfather’s word in Hoffa vs. The United States. I laughed, but it got me thinking, not just about what he’d say, but how do you fish out the turd, and clean the pool for kids like Hope. That’s what I wanted to discuss with my buddies in the state department. ↩︎