1979 Rumors

Love is patient and kind; love does not envy or boast; it is not arrogant or rude. It does not insist on its own way; it is not irritable or resentful; it does not rejoice at wrongdoing, but rejoices with the truth.

1 Corinthians 13:4-6

Wendy carefully cuts my picture out of the newspaper and tucks it between pages of my Karl Fueves coin magic book from the White Hills Elementary book fair. Even though I was the smallest and youngest kid in second grade, I was a famous artist and chosen to be on the morning Buckskin Bill Black show with Mr. Green Jeans and the talking moose puppet that introduced Popeye cartoons.

Reporters from the Baton Rouge Advocate even showed up at the studio to take my photo and interview me. Only people who were awake at 8am on Saturday saw me on television, but everyone in Baton Rouge read the newspaper and saw me in it the next day. My dad had been in Arkansas without a television or phone or newspaper, but I knew he’d be proud of me. Wendy was. She even took me to a fancy barber to cut my hair and hide my scar before driving me to the studio, and she bought a newspaper at the 7-11 just to show me my picture. In the photos, my hair looked nice. It was long and wavy and soft from the fancy soap the barber used, though you can’t tell that in the photo.

I tell Wendy how much my dad will like seeing me in the paper, just like Big Daddy. He was almost always on the front page lately, though he wasn’t in the one with my picture. He was also on television news once a week, with his face filling the screen and talking in his smooth voice for everyone to hear. The reporters probably confused him with my dad. I repeat that my dad will like seeing me in the news, and say when we go see Grandma Foster I’ll give her the clipping so she can put it with her scrap book of Big Daddy’s news pictures. I also tell Wendy that I can’t wait to see Tiffany and show her that I had become a famous artist, just like she had taught me. Janice would sometimes pick me up so we could play and draw at Aunt Reece’s False River camp, but I hadn’t seen either of them in forever. At least a year, since I was a little kid in first grade and won the class talent show (along with about half the class; each of us won some type of award). But I still felt Tiffany was my oldest friend. In second grade, I’m best buddies with the teacher, but for some reason I don’t fit in with the kids in class. I’m popular, being asked to do magic tricks at show and tell and to help kids draw animals, but at recess and lunch I usually talk with the teachers like I used to talk with MawMaw all day. They seem to talk about things more practical than the kids, like what’s going on in the newspaper and how Big Daddy helped the teachers union and they’ll never forget it. And they can’t get enough of me making that little red handkerchief disappear in the thumb tip Cindi gave me last Christmas. Kids were just kids. When my dad picks me up, we sometimes see Janice and Mamma Jean in False River, and sometimes Grandma Foster by the airport, and sometimes – though rarely – Big Daddy at Teamsters Local #5 off Airline. When I’m with my dad, we drive all over town, sometimes to see family, but mostly to see his girlfriends. He says women like seeing him with me, that I’m handsome and funny and a magnet and can stay awake all night honky-tonkin’ with him and his friends. We never see other kids, thankfully.

We’re in Wendy’s first house without shared walls, a delapitated and musty smelling two-bedroom one-bath in Baker, a half-Slushie north of Glen Oaks and the airport, closer to her new job at Exxon Plastics Plant that she got after typing for them through Kelly’s Girls. She loved that house. It had a living room sized back yard with an aging chain link fence bowing and undulating around a plywood doghouse that was peeling apart from rain. We were lucky: I could see at least a dozen other back yards, and we were the only one with a doghouse.

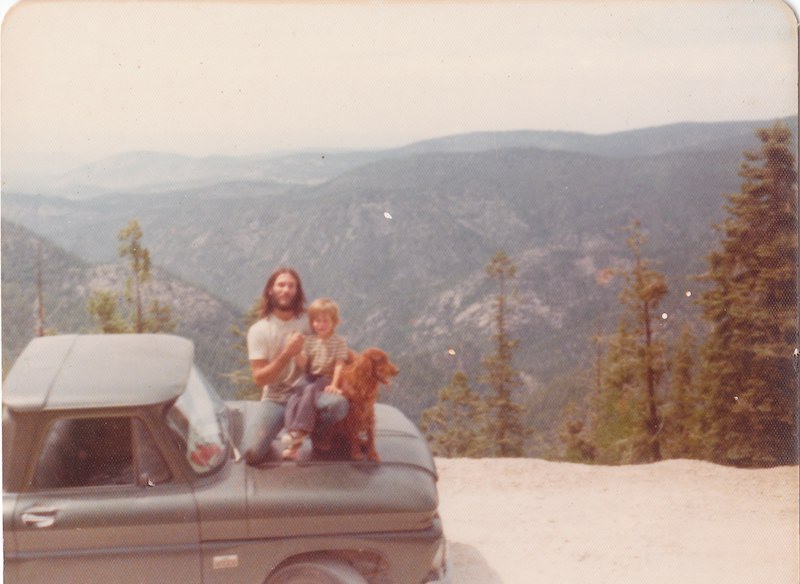

On the far side of the doghouse, tucked in a corner that received the most sunshine, she was nurturing a small raised bed garden. It finally had a couple of tomato plants and a zucchini bush. She had spent the winter panting and sweating and tilling topsoil into the clay on her days off work. She smiled the entire time, saying how much she loved having her own patch of dirt. One day, she said, we’d be able to afford an Irish Setter just like Anne for the dog house. I asked why not take in one of the dogs running around the neighborhood, or one of Anne’s puppies she had in Arkansas, and Wendy said that even a free dog has to eat and go to the vet, but that her new job was a good one and that soon we’d be able to do all kinds of fun things we never could do before. She was happy, and always adding plants to the yard and packing mulch around them so they’d grow healthier. And she’d add some of Craig’s artwork here and there to make the home more colorful and to hide the peeling wallpaper and flacking plaster. She seemed to get more done when I wasn’t home, and whenever I returned from visiting my dad in his Arkansas cabin or in one of Big Daddy’s houses in Baton Rouge there was always something new she had done for our home. She would sometimes keep Anne while my dad and I zipped around town, and had grown to love her as much as I did. It’s no wonder she wanted an Irish Setter to love the doghouse as much as she loved her home.

I tuck my book in the backpack of clothes Wendy packed for me, put the kid-sized double-bladed Old Henry PawPaw gave me in my pocket, and drape the Kennedy half dollar with a square necklace hole from Brian the one armed drug dealer around my neck using what he said was a dog tag chain. (It must have been for a very small dog.)

We hear my dad drive up and I rush out to see him and tell him about being on Buckskin Bill, but I see Anne jump out of his truck and I forget everything but her. She leaps over to me and I squat to receive her shugga’ all over my face. I rub her ears and hear my dad tell Wendy to keep her for a week while he takes me. He beckons me to his truck, a different one than before but still just a big truck, dirty and dented with Arkansas mud from his gardens caked in the wheel wells. I hug and rub Anne goodbye, then step into Wendy’s open arms and hug her, too. My dad barks again, and I grab my backpack and trot to the jeep, toss it in, and hop on board. We zip backwards and he speed towards the I-110 onramp headed south.

He seems agitated and fires up a joint, so I wait to tell him about me and my art being in the newspaper. It was a drawing of a deer and a poem. I mimicked the words from the teacher’s example on the chalk board, something about a brown dog, but I added a drawing and put enough of my personality into it to be newsworthy. My poem was: “Brown Deer, Brown Deer, What do you see? I see shooting arrows, coming at me.”

I traced each letter on lines the teacher made on a poster board as wide as my two hands held apart, and above the poem I drew a humongous deer. It was nothing more than a big rectangle for the body and a small rectangle for the head, with scraggly antlers and stick-figure legs and big round eyes like a deer caught in headlights, but the mishmash of shapes conveyed the essence of a deer as effectively as Picasso portrayed humans. The deer’s death was obviously imminent. I drew 13 arrows coming at it from all different directions. One arrow even came straight up from the ground. I had no idea how someone could be lying there and shooting up, but when I only had 12 arrows it looked as if the deer could duck down to the bottom left corner and avoid them, so I added one more to be sure that no one doubted his inevitable demise.

Five other kids from other schools were on Buckskin Bill Black with me, but the reporters were most interested in me. They gathered around and gave me more attention than they did to either Mr. Black or Mr. Green Jeans, and they all knew my name even before I told them. It was as if they couldn’t believe that Jason Partin was there, the son of Edward Partin, and they even asked if my dad would show up. I told them no, but that I learned all about hunting deer from him. They were interested in that, and I showed them my drawing and they were impressed by all the arrows. I told them that after you kill a deer, you gut them to spill out the innards. I had forgotten my Old Henry, so I used my finger so show them where to slice the rectangle and spill the most guts with one swipe. I said to be sure to keep the blade sharp so you don’t have to push hard and can slice skin without accidentally nicking the intestines, but that if you wanted to gut a man it didn’t matter if you nicked anything. In fact, the more you shoved and sliced the better. But, of course, if you can, aim for between the ribs, just like with an arrow, because a deer dies faster when you puncture the heart or lungs. When you pierce real deep, it bleeds to death silently.

They all listened intently and asked lots of questions, but I knew better than to share secrets with them and they must have gotten tired of trying. I may have even offended them, because when the cameras began filming, they had me read my poem but chose to focus on another kid for the question and answer sessions. That little twerp didn’t even have artwork, he just tucked his hands in his pockets and swayed back and forth, and told everyone about how education could change the world. Boring.

I wait for my dad to be ready before talking to him. The joint relaxes him, but before I can tell him about Buckskin Bill he puts the joint in his mouth and points past my face and out the window. We’re flying along the raised interstate above downtown, higher than most buildings. I don’t see what he’s pointing at. Despite the joint dangling from his lips, he says in a remarkably clear voice, “Look, Justin – I mean Jason goddamnit – over there.”

I don’t see anything remarkable. The new state capital is there, the tallest one in America, and behind it is the Mississippi River and the bridge going over to Plaquimine and the cement factory. Beside it is the old state capital on a small hill, the castle that Mark Twain called an eyesore and where PawPaw took me sledding on a cardboard box.

“That’s where we’ll see Stevie Nicks! Man, she’s fine!”

I’m unsure what he means. I sit silently.

“Look, son,” he says, and grabs my head like a Harlem Globetrotter holding a basketball from the top. He moves my head to keep pace with our speed, and I see what I think he sees, a brand new dome between the old state capital and the bridge, The Baton Rouge Centroplex. I had never seen it before – it was built in 1977 – but Wendy would soon take me there to see the Harlem Globetrotters and it would become a downtown fixture. That must be what he wanted me to see, so I tell him I see it now. He lets go of my head and takes out this joint.

“That’s where Stevie Nicks will sing. Man, she’s fine!”

He takes a hit from his joint, points to my floorboard, and without exhaling mumbles, “Reach down there and grab that 8-track.”

I rummage through the empty candy wrappers and crushed beer cans and grab the first one I see.

“No, son! That one,” he says, pointing with his joint in hand. His arms are so long he could have almost grabbed it by himself. The smoke from his joint is right under my nose.

I reach down and pick up the 8-track he meant, and he taps to the photo of Stevie Nicks on the front and makes a noise like Anne expecting a treat. He takes it from me and shoves it into the player. He tells me to push the button. I try, but it feels stuck. I push harder, and my finger buckles. I try my thumb, but the angle is wrong and I can’t get my body behind it.

“Here, son,” he says and pushes my thumb with his finger. The button sinks in, and he grins broadly and tells me I’m getting stronger but have a ways to go. Second Hand News ramps up faster than us accelerating onto I-110. He pinches the remnants of his joint and brings it to his face. It vanishes into his beard and he takes a final hit before dropping the roach in the ashtray. His hand finds the steering wheel, and he taps his fingers to Fleetwood Mac’s epic 1979 album, Rumors. His stares forward and his face beams. I can’t help but tap my fingers against the glove box in sync with him.

“She’ll change clothes between every song,” he says. His grin is contagious, and I grin and match his fingers beat for beat.

He looks me in the eye and his grin widens and he says, “She wears fine outfits and dances for you.”

I say that sounds fun. He rubs my head and tells me he’s proud of me and he loves me. I tell him I love him, too. “This Saturday,” he says. “This Saturday,” I echo. He taps the steering wheel hard and fast and out of sync with Second Hand News, but with a huge grin and a sparkle in his eye, and he makes sounds like Anne anxiously waiting for me to serve her dog food.

“Hold the steering wheel, son,” he says in a boyish voice.

I reach over and take hold with both hands. He doesn’t really let me drive. His left knee is pushed up and against the wheel and he’s always been able to steer like that. He just likes having me practice so I’m ready when I’m old enough to drive. He mostly watches the road while he rolls another joint. He’s really fast, and he lights it and retakes the wheel just as Dreams comes on. He takes a big hit and turns the dial up. We cruise along what’s turned into I-10 and no longer above downtown, singing along with Miss Nicks.

He finishes the joint just before pulling off I-10 east and navigating to Arline Buelevard. We pull up to Local #5. Big Daddy’s in the parking lot with a bunch of reporters. Doug is beside him, and so is Keith; they look so similar it’s like three big blonde brothers in charge of the army of huge Teamsters surrounding them. We get out and wait. My dad seems either confused or stoned silent. The reporters leave without asking me about my stint on the Buckskin Bill show; if they noticed me, they were sly enough to not let anyone know. My dad walks to the men. I stay by the truck. For some reason, I felt uncomfortable around Big Daddy, and when we visited I acted like my dad was acting while we waited for the reporters to leave. Even from afar, whenever Big Daddy starts talking everything seems to melt away other than his face and voice. Today is different. He’s not smiling. He still dominates my mind’s eye when I look back, but there’s an intensity coming from everyone else that overrides his dominance. He sends the gang of Teamsters inside. Doug follows. Keith and my dad talk with Big Daddy. My dad’s voice raises, but I don’t hear what he says. Big Daddy’s elk skinning knife materialize in his hand, and my dad’s quiet again. The knife vanishes, and he and Keith walk inside Local #5 to join Doug and the other huge men as if nothing happened; in fairness, you get used to Big Daddy quieting my dad after a while.1

My dad returns to the truck and we take off. Airline is long and straight. It’s what people used before the interstate. He rolls a joint without asking my help driving. He’s focused on driving with his knee, and I know to not say anything. About a half joint away, we turn onto a side street I don’t recognize, and a few turns later we’re on Florida Beulevard, near the Chinese Restaurant where Wendy and I briefly lived. We turn into a neighborhood behind the Little Saigon strip mall and across from the Chinese Restaurant and pass all the Vietnamese family homes. Three quick turns later, we pull into a driveway across from Belaire High School. The brick home windows are covered with newspaper from the inside, and there are no trees. My dad tells me to wait, and he finishes the joint and drops the roach in the ashtray. As usual, finishing a joint puts him in a good mood. We hop out and walk inside. The windows are all shut tightly. The AC is blaring, and my faint arm hairs rise with the goose bumps. The dank smell of freshly harvested pot swirls around us.

It’s a three bedroom, two bath house with no furniture in sight. A woman is there who looks a lot like Wendy, and she rushes to him and jump into his arms and gives him big and long kiss. She says hi to me and leans over to give me a hug. Her baby cries, and she steps into the back bedroom to bring her out. The baby stops crying in her arms, but she can barely hold her with the heavy and bulky leg casts on her. My dad takes her and effortlessly cradles her in one arm. He gently puts his finger to her lips and makes little noises.

“Your dad’s a good man,” the woman tells me. “You’re lucky he loves you so much.” I tell her I know.

“She was born with deformed legs,” my dad says of the baby. “The doctors broke them and straightened them.”

I know that must have hurt; my broken arm and cast had. I walk over and reach up and point at her face and make little noises, too.

“Your dad paid the hospital bill,” the woman says. She isn’t looking at me, she’s staring up at my dad’s face with a wistful countenance. “In cash,” she adds. “I don’t know what I would do without him.”

She takes the baby and puts her back in the back bedroom. I drop my backpack beside a sleeping mat in the living room, squeezed between all of my dad’s camping and hunting gear. We get to work in the bedroom next door to the baby’s room.

A dense inverted jungle of pot plants hangs from hooks in the ceiling. On the floor is a mechanical scale shaped like my Zodiac sign, the Libra scales of justice and balance. Beside it is a haphazard pile of boxes of plastic sandwich baggies from a grocery store. My dad picks buds the pot plants and adds them to a few black plastic lawn bags packed with pot and piled in a corner of the room. I get to work measuring 1/8 ounce piles of buds and putting them in the sandwich baggies. The woman plays with her baby in the next door room, making soft noises and giggling a bit.

My dad pauses and watches me with a proud smile on his face. He stoops down and double-checks one of the rolled baggies. The scale’s little needle bounces and settles on zero. He beams and says I did a good job. But, he adds a couple of extra buds to the few bags I had already rolled, and tells me he likes to give a bit extra to people, even if they don’t know it. Debbie LeBeaux calls that lagniappe. I nod and say I understand, and continue bagging. This time, I add just enough extra bud to tip the scale from zero to touch the top.

The woman boils hot dogs while we finish working. She tells us they’re ready. There’s no table, but she proudly steers us to an eloquent display on the kitchen counter with a roll of paper towels, three paper plates, a plastic bag of Wonder white bread, and a glass bottle of ketchup. There are three stools, and my dad helps me up into mine. He and I wrap a wiener in a slice of Wonder bread and it with ketchup. I can’t recall what she did with hers, but we all dive in and laugh about things I don’t recall. My dad devours two by the time the woman and I finish ours.

She uses her paper towel to wipe ketchup off the rim of the bottle before putting it back in otherwise empty refrigerator, throws away the red-stained plates, twist ties the bag of bread, and wipes off the counter, and winks at my dad. She says she’d like to take a nap. He tells me to watch the baby, and they go into the master bedroom across from her room.

She’s sleeping, so there’s not much to do. I go into the jungle room and practice rolling a joint. I try to do it like Brian, with one hand, but that’s harder than a one handed Charlier cut of cards. I try with both hands and fail that, too. I feel myself getting as frustrated as trying to open a taped up box without a knife. To make matters worse, the baby starts bawling. I get up and walk to her room, but hear my dad say something mumbled and open his door instead.

He and the woman are wrestling on the bed. They had worked up such a sweat that they took off their clothes. She’s winning. She’s on top of him, and even though he has both of his hands locked around her waist he can’t get her off. She sees me and looses her concentration and falls off and pulls a blanket over them. My dad keeps his cool.

“Justin – I mean Jason,” he says. “Get the baby to stop crying.” He used her name, but I can’t recall it. I nod and pivot around.

“And close the door,” he shouts after me. I oblige.

I walk into the baby’s room and stand by her crib. She was on her back. Her cast went above her hips. She wore a diaper, like all babies, but it was very big to stretch around the cast. It covered a hole the doctor left between her legs. I push a toybox beside the crib and step onto it. I reach down and heave her up so she balances on her cast legs. She won’t stop crying. I put my finger to her lips and make those little noises again, but she won’t stop. I try again, but she won’t listen. I grow frustrated and use my serious voice to tell her to stop crying. She won’t. I point my finger between her eyes, and tell her to shut up. She won’t. I slap her gently across the face and point my finger back between her eyes and once again I tell her to shut up, but she cries more loudly. I slap her harder, and she cries harder. I slap her real good, and she finally stops and stares at me and gasps for breath. I smile, knowing I did what was asked, just as the woman walks in.

She’s wearing one of my dad’s shirts that covers almost to her knees. She rushes over and picks up her daughter and the red hand print on her face, then looks at me with anger in her eyes. She says nothing, but spins around and rushes to my dad’s room.

“Jason was slapping the baby,” she says in a terrified voice. She used the baby’s name, like my dad did.

“What kind of boy does that?” she demanded of him.

I don’t recall what he said in return, but she rushes around the room, carrying the baby and trying to find her clothes. He puts on blue jeans and a shirt, and takes the baby. He and the woman bicker back and forth while she darts around the room gathering her things. She shoves everything in her backpack and takes the baby and storms out the house. My dad follows her outside, and I sit by my mat in the living room and shiver. It’s not just the cold AC behind closed windows, I’m scared and wonder what I did wrong.

My dad walks back in and sits beside me. He’s silent, too. He puts his arm around me and brings me close and hugs me. His chin is on the top of my head, where he usually grabs me to show me something. He doesn’t say anything, but I hear him sobbing. At least a minute later, he pulls me in front of him. His eyes are wet in the corners.

“I love you, son,” he says in a soft voice.

“I love you, too, dad,” I say. He smiles and hugs me again.

We don’t see the woman again, but that doesn’t seem to slow us down from working and getting ready to see Stevie Nicks. Within a day or two, my dad’s talking about how fine she is again, and when we drive past Belaire to get Chinese food we play Rumors and take the long way around Florida sing along to at least one song there and one song back. He drives slowly, not running stop signs and never speeding, probably so we can hear a whole song on the short drive.

Saturday finally arrives. We stop at a 7-11 by the Chinese restaurant and my dad picks up a case of beer in cans. I can’t recall the brand, but it’s definitely not the Miller Lite pony bottles PawPaw drank. My dad had a fondness for a Canadian beer called Moosehead, but that was in a bottle and only in the fancy liquor store, so we probably had a case of whatever was cheap and cold. He buys me a six pack of Dr. Pepper, and both of us a few Turtles. He sets the case and six pack between us on the bucket seat and sips it while driving down Florida Bulevard towards an interstate onramp. I’ve either gotten stronger or learned to shift my body and put my weight behind my thumb, and my dad tells me I’m how proud he is of me and how the 8-track player is mine for the ride. He taps his finger on the steering wheel and we sing along to Miss Nicks without a care in the world. A full joint later, we arrive at the Centroplex. He pulls along the levee and heaves the steering wheel lever up. It clicks into place with a thud. He turns off the truck, then turns the key a bit back so we can play Rumors while we wait for the show.

Two beer cans were added to the floorboard on the drive. He opens another and rolls a joint. I take big gulps of my Dr. Pepper, trying to match his pace. A few beers and two joints later – and two pees by me and one by him onto the levee beside us – we lock the truck and walk past the old state capital and to the Centroplex.

For some reason, he has to use his serious voice and point his finger at the ticket counter. He points at them and then at me, and then back at them. His eyebrows narrow. A few harsh words later, he has a ticket to the show and we’re walking to the row of double doors and mingling with hundreds of people who smell like pot and bounce around me and bump into me with their knees and hips. Someone spills a beer on my head, but quickly apologizes and says they didn’t see me. My dad heaves me onto his shoulders, and I have to duck through the doors. Almost immediately, I run into a wall of smoke and can barely breathe. Within a few breaths, though, I’m relaxed and feeling as groovy as a Fleetwood Mac 8-Track.

We marshal our way to a booth selling beer and my dad buys a big one, one of the supper sizes like the ones in New Orleans that say “huge ass beers to go,” and push and shove our way to stage right, almost touching the metal gait in front of the stage and about 20 feet from center stage. I look around. I’m the tallest one, taller than the front of the stage and able to see all 10,000 people behind us. A bunch of hands wave at me, and everyone around us cheers and says how cool it is that I’m there. My dad beams. His beer is empty, but the guy next to him hands him a joint. He keeps one hand on my legs and takes the joint and starts passing it back and forth with the people circling us. Smoke rises, and I feel fine.

The lights dim and everyone hoots and hollers. My dad’s arms wrap around my legs and his hands form a horn around his mouth, and he hoots and hollers louder than anyone. A few instruments start to make beats, and the crowd hoots in unison. Stage lights come on, and the band is in front of my face. The most beautiful woman I’ve ever seen walks on stage, and I have to cover my ears from the sound of 10,000 fans celebrating Stevie Nicks. She launches into a song, and the totem pole that is my dad and me comes to life and we dance in perfect harmony. She sings to me and I rejoice as if Jesus had blessed me with a lotta bucket perpetually full of fried catfish. Just like my dad said, she changes dresses between songs and gives everyone time to roll more joints. Miss Nick returns wearing skin tight pants and a flowing colorful blouse that makes her look like a butterfly flittering across the stage, and she lands by the microphone at center stage and launches into Dreams. I know the words now, and I sing along with her, dancing atop my dad’s shoulders as he moves in sync. All of our practice in the truck pays off, and when Miss Nicks leaves to change clothe again everyone around us cheers us and slaps my dad’s back and reaches up and pats my thighs. My dad’s face twitches with the delight of Anne getting her butt rubbed. Miss Nicks comes back on stage, and we party all night long.

The band leaves and the lights come on and my dad practically drops me to the sticky floor. He takes my hand and stumbles in the general direction of the doors. I have to pull a couple of times to remind him where they are. We zig zag to the levee and put it on our left shoulders and walk towards the castle on a hill. The truck must have moved, because it takes us forever to find it. My dad fumbles for his keys and drops them a couple of times before opening the door.

He plops in the driver’s seat and says, “Justin… I mean… Jason… You gonna drive.”

I say sure, and he pulls me onto his lap and shuts the door. I grasp the steering wheel with both hands, but in front of it this time. I’m ready.

“I’ll work the… gas and brake,” he says, looking down at his feet. His head lingers a moment, then he pops back up and says, “You steer. We’re going to Sonny’s. I need to sober up.”

I know where Sonny lives. It’s a tiny house in Spanish Town, almost a beer can throw from the new state capital and only a few blocks away from where we’re parked. I clutch the oversized steering wheel with hands spread wide apart, and my dad starts the truck and I feel the rumble in my chest, though I can barely hear it for some reason. He reaches his arms around me and holds the steering wheel below my hands, clunks the gear shift down, and eases forward with the same care he used driving around Belaire. We crawl forward.

A few blocks later, he halts at a stop sign. I stain and rotate the steering wheel to take a right, and we continue up the small sledding hill towards Spanish Town. Another two stops and a turn later, we park on the street in front of Sonny’s house. The porch light is on, and he opens the door as if expecting us. He’s wearing his bath robe and cheerful as always. He welcomes us in, and my dad plops on the couch and I sit beside him. Rumors is playing on Sonny’s record player, and the album cover is on his coffee table with a small pile of powdered sugar like we dump on beignets at Coffee Call. He remembers my name, and asks me about the show as he plays with the sugar with his driver’s license. I tell him all about Miss Nicks and her butterfly dress and dancing. I say we were honky-tonkin’, and Sonny and my dad burst out laughing. Sonny slides the album to my dad, and he’s so hungry he snorts the sugar. Sonny must have been hungry, too. We had eaten all the Turtles. I said I was hungry and wanted some sugar. My dad’s laughing now, and says no, that it’s cocaine and for adults only. He tells me it wakes him up so he can drive us home, like coffee but better. Sonny agrees, and gets up and grabs a thin rectangular box of Fig Newtons from his kitchen and hands it to me. I devour about half of them. My dad and Sonny make a fresh pile of powder and talk about Rumors, saying how they did the whole album high on cocaine. Both mention Miss Nick’s ass a few times. They make another pile and finish sobering up, then my dad pulls a baggie of weed from his pocket and tosses it onto Sonny’s coffee table. We hang around for a joint and few songs of Rumors – I know all the lyrics, and that makes them laugh – then we get up and get back in the truck and he drives us to the I-10 onramp. We fly over downtown again.

The Centroplex is hidden in darkness. It must have been past 2am, and my eyes keep closing and my head keeps falling forward. I roll down the window to get some air. I tell my dad I wished I had some cocaine to wake up.

He whiles on me suddenly and shoves his finger into my face, right at my nose. In his most serious voice, he tells me, “Don’t you say cocaine around anyone! Don’t tell anyone what I do with Sonny.”

I’m wide awake now, staring at his finger and nodding in agreement. We drive a remarkably long time with him looking at me instead of the road. I say the words, “I promise I’ll never say that word again.” Satisfied, he lowers his finger and looks ahead. He swaps hands on the steering wheel and rolls down his window, too. He takes a deep breath from the wind and returns to smiling. He swaps hands again and pats my leg.

“Wasn’t she fine!” he says rhetorically. “That dress! That ass!”

He continues on about Stevie Nicks for a while. I’m still shaken from being woken up so abruptly. I remain silent, but I agree with everything he says.

My dad’s always woken up at sunrise, but he lets me sleep in most of the day while he packs baggies. After hot dogs for lunch, he drives me to Wendy’s so I can get ready for school and he can pick up Anne. We pull into the driveway and see Wendy standing by the front door. Anne’s sleeping on the concrete beside her feet.

I hop out and pause. Something’s wrong. Wendy’s sniffing, and her eyes are puffy. My dad rushes past me and shouts, “What happened?” Wendy steps aside and my dad drops to his knees beside Anne. I see dried blood pooled around her.

“Nooo!” he shouts.

Wendy sniffs and says, “She crawled home. She jumped the fence.”

My dad starts bawling. I’m not sure he’s listening.

“I went looking for her,” Wendy said, looking at her feet. “I walked to the woods and looked for her all morning. She crawled home… I found her here…” her voice trails off, and she begins sobbing.

My dad rolls Anne over and inspects the bullet hole in her ribs. It was about the size of a .22LR, what I’d use to shoot a squirrel or a rabbit. It would have barely slowed down a deer, even if it nicked a lung. She must have suffered and bled to death slowly. I know this, but I don’t know what I feel. I’m confused. I think I was feeling their feelings, and it was a combination of love, loss, sadness, and anger. That’s a lot to process for a kid who’s still hung over.

My dad ignores us. Silent except for sobs and focused on nothing but Anne, he scoops her up with both hands as gently as if she were still alive. He stands straight. Tears flow down his cheeks and disappear into his curly black beard. His eyes are so narrow that I can’t see whites, only the dark brown Partin eyes that are so dark they seem as black as his beard. His whole face is a black hole of pain, drawing me into it but not allowing him to see anything other than his anguish. He takes a deep breath and tries to look as strong and brave as he tells me to be, but he fails. As tall as he is, all I see the little boy in Where the Red Fern grows carrying his Anne to bury her.

And that’s what my dad does. He walks to the back yard and sets Anne down beside the doghouse that had always been there, probably since before I was born. Anne only got to use it that week. She must have wanted freedom and jumped the fence or squeezed between one of the wobbly chain link sections. She wasn’t a dog meant for crowded neighborhoods, and probably ran to the woods and imagined she was back in Arkansas, hunting squirrels with me.

My dad walks away and I kneel beside Anne. The bullet hole seems intentional, as if someone aimed where you’d shoot a deer, but missed just a bit. And they used a .22. It must have been a kid who didn’t know better. I feel anger, but I don’t know why. Still, I haven’t processed Anne’s death. I had seen lots of dead animals, but I had never known any of them before shooting them. I hadn’t yet woken up without Anne. I felt confused at how I felt, but I recall anger at whoever shot her and made her suffer. If my dad and Big Daddy taught me anything, it was how to kill quickly so nothing suffers; I was too young to consider survivors suffering much longer than the most drawn out death of a loved one. I pet her. Her fur feels the same, but her body is cold. She’s begins to stiffen, and so does my heart. I’ve never felt such anger. I’ll never do that to someone. I’ll become the best shot on earth. I’ll stop other people from killing any dog. I’ll never feel this way again.

He returns with Wendy’s shovel and remains silent and focused. The black hole of pain had been replaced with concentrated effort at digging a grave. The spade cuts into the clay like a knife through butter, infinitely faster than Wendy when she nurtured her garden. He doesn’t pause, not even when his breath begins to puff loudly. He doesn’t talk, but he doesn’t sob any more. He fixes his gaze on wherever he’s aiming the shovel, and stabs the blade with the precision of a surgeon and the force of a gladiator. Clumps of clay pile between the hole and doghouse. He has to stoop over to reach the bottom of the hole. It’s deep enough, but he keeps digging.

Finally, he stands up and jams the shovel into the now tall mound of clay. His face returns to almost normal. I can see the whites of his eyes again. But his countenance isn’t the same, it’s detached as if he were very stoned. He reaches down and grasps Anne’s increasingly stiff body, and in one motion heaves her into the hole with a carelessness the exact opposite of when he cradled her earlier. She lands with a thud, her body bent sideways towards the deeper part of the hole. Still wordless, he grasps the shovel and begins moving the pile of clay back into the hole. He finishes and carries the shovel away without a sound. I kneel by the grave. The mound is smaller than I expected, as if Anne had somehow snuck out before he began filling the hole. I imagine she wanted to be free, and ran off to the woods to chase squirrels.

I hear my dad’s voice booming from inside. I leave and walk around to the front and into the kitchen. He’s shouting at Wendy and pointing his finger down into her face. Her arms are wrapped around each other, as if she’s hugging herself, and her head is tilting towards her feet. My dad glances at me, looks back at Wendy.

He shouts, “You can’t even look after a goddamn dog!”

He pops his finger into one of her shoulders. Her body twists a bit, but she twists back to the same stance.

“How the fuck can you look after our son?”

She hugs herself more tightly and remains silent. Her gaze is locked on her feet. I can barely see her eyes, but they seem mostly closed.

“Let’s ask him!” He looks at me and bellows, “Justin – Fuck! I mean Jason. Where do you want to live, with me or Wendy?”

I say in Arkansas. I’m not sure where that burst of diplomacy came from. Maybe it was his phrasing. Regardless, they misunderstood me. My dad whips around and pokes Wendy’s shoulder again and says, “See?” This time she stays slightly twisted. Her shoulders jitter, and I hear a muffled sob.

He leaves after they agree that I’ll begin spending summers and holidays with him in Arkansas. But, because his cabin is almost 30 miles from any town and down five miles of 4X4 dirt and rock roads without a phone or a television, I’ll live in Baton Rouge for school. He’ll bring me back just before this time every year, when he hauls his garden to town to sell.

That night, Wendy pours a warm bath for me and puts my favorite toys inside. We’re both quiet. She adds some Mr. Bubble. She hasn’t stopped looking down towards the floor, even when bent over the bath tub, stirring the water to make bubbles. I’m no longer angry, but I’m still confused. I don’t know what to say, and Wendy hasn’t said anything other than she’d make me a bath to get the clay off my hands and to wash my hair. I hadn’t bathed since I left a week before, and my hair was almost as dirty as Anne’s. I still haven’t woken up without her, and I still don’t realize how badly it will hurt to not have Anne tomorrow. Wendy must have, though, because she starts crying. Not sobbing, but crying. On her knees and leaning over the rail of the bathtub and crying softly but without pause. Tears drip from her cheeks and land on and between bubbles. Her body deflates a bit with each tear that leaves, and soon her hands are limp on the tub and her head lays listlessly atop them. I’m holding my bathtub dolphin and, for reasons I can’t recall or fathom, my bathtub giraffe. A few other toys float among the bubbles and Wendy’s tears. I start crying, too. I now know what sadness feels like. It hurts worse than my head scalping or my broken arm, more than a mound of fire ants attacking my body. I’d rather be angry; it hurts too much to be sad. I cry more loudly and that’s what finally gets Wendy to look up. She sniffs back snot and pets my head, obviously remembering Anne and how my soft wavy auburn hair had looked so much like her fur. She’s breathing irregularly, regaining herself one puff at a time. She tells me shhhh, and says she loves me. I can’t stop crying enough to answer. She’s patient with me, though. She sobs a bit now and then, but focuses on washing the clay from my hair while I clutch the dolphin and the giraffe as tightly as I grasped my dad’s steering wheel.

We cry together until the bubbles are gone and the water is tepid and I’m clean again. She lets me dry myself, and lays out my clothes for school in the morning, and gets ready for bed so she can go to her new job at Exxon. She had been proud of that job, it let her afford the house, and one day she could afford an Irish Setter, too. I put away my backpack of dirty clothes, and realize I never showed my dad or Big Daddy the news clipping of me and my artwork.

Go to the Table of Contents

Footnotes:

- After Jimmy Hoffa vanished, Big Daddy lost his federal protection and was sentenced eight years in prison. In 1979, he lost his final appeal, and was about to leave for a federal penatentery in Texas. Ostensibly, Doug would take the reins of Baton Rouge Teamsters Local #5 while Big Daddy was in the big house. The members unanimously voted to keep paying Big Daddy his salary, even though he’d be in prison, which is what I think was happening when I remember seeing him before he left the state. That may not be surprising if you learned why he was sentenced. A news article skimmed the reasons, but missed the point, probably because everyone in America was still fascinated about Hoffa and his 1975 disappearance .

ALEXANDRIA, La., April 9 (AP)—Edward Grady Partin, the Baton Rouge Teamster leader whose testimony helped send Jimmy Hoffa to jail, was sentenced today to eight years in prison.

United States District Judge Nauman Scott imposed fouryear sentences for each of three counts of obstruction of justice. He said two of the terms were to run concurrently.

Mr. Partin was convicted last month of conspiring to keep two witnesses from testifying against him in a 1972 trial in Houston, Tex., and conspiring to keep one of them away from a New Orleans grand jury.

He was a surprise Government witness in Mr. Hoffa’s trial 11 years ago on jurytampering charges.

He was originally charged with stealing $450,000 in cash from the Local #5 safe. Police discovered the safe beneath the murkey waters of a river by our house, empty and without fingerprints. The only two witnesses were Local #5 Teamsters, and they were found beaten and bloody; the survivor refused to testify. The rest of the local Teamsters decided Big Daddy should be paid while in prison. The final verdict was obstruction of justice, related to a long series of trials and mistrials that began around the time I was born in 1972 and ended soon after the 1979 Fleetwood Mac Rumors tour. ↩︎